Abstract

Infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) is a rare and catastrophic postoperative complication. The aims of this study were to investigate the diagnostic, treatment and rehabilitation measures for postoperative infection following after ACLR. A retrospective study was conducted on 1500 patients who underwent ACLR between January 2011 and January 2022. Twenty patients who met the criteria for summarizing the incidence patterns and treatment experiences were selected for a complete investigation of their diagnostic, therapeutic, and rehabilitation processes, as well as outpatient follow-up results. Among the 20 patients who developed postoperative infections, Staphylococcus aureus was the main pathogen (80%). The clinical manifestations mainly included fever (80%) and knee joint pain (100%). Laboratory tests demonstrated that C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were greater than 50 mmol/L in fifteen patients (75%). All of the patients received intravenous antibiotic therapy. Five patients (25%) of tendon socket infection were treated with continuous negative pressure suction irrigation, whereas the other fifteen patients with intra-articular infection were treated with arthroscopic debridement and continuous flushing. The Lysholm score of the affected knee was compared before treatment and 6 months after treatment, and the difference was statistically significant (t = 20.78, P < 0.001). The success rate of treatment was 100%, and there were no significant differences between patients who received secondary treatment and functional exercise and those who underwent ACLR in terms of knee joint function or range of motion during the same time period. Infection was rare after ACLR, however it was fatal, and the main pathogen was Staphylococcus aureus. Early diagnosis and a comprehensive treatment approach are pivotal for the successful management of postoperative infections following ACLR. The results of this study contribute valuable clinical insights for further refining surgical procedures, enhancing infection prevention measures, and optimizing rehabilitation protocols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is an intra-articular and synovial component of the knee. It plays a crucial role in preventing excessive anterior translation of the tibia on the femur, avoiding hyperextension of the knee joint, and contributing to rotational stability1. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the most common ligament injuries in the knee joint. According to statistics, among individuals aged 16–39, there are 85 ACL injuries per 100,000 people, morever, in the United States, there are 100,000 cases of injury annually2,3. The most prevalent mechanism of ACL rupture is indirect and uncontrollable torsion of pivot displacement, which consists of varus and internal forces imposed on the knee at flexion angles between 10° and 20°. It is commonly assumed that anatomical ACL reconstruction can restore orthostatic and rotational stability. However, graft selection is contingent on various parameters with clinician and patient preferences being the most essential factors. Bone-patellar tendine-bone autografts, hamstring autografts, other autograft tendons, allograft tendons, synthetic materials and combinations of various graft types may be used for ACL reconstruction4. However, ACL repair does not require the selection of a graft. ACL repair is a surgical method for treating ACL injuries that aims to preserve the original ligament without using external materials. Due to the fact that no grafts are used in ACL repair, it is associated with a relatively lower risk of infection. Despite promising early results, the high rates of medium- to long-term failures have led to a shift towards ACL reconstruction2,3. Reconstruction of the ACL is the most popular and traditional procedure for treating knee injuries, and arthroscopic assisted ligament reconstruction is the primary method for restoring joint stability5. However, there are risks associated with ACL reconstruction, including infection, joint fibrosis, and postoperative reduced range of motion. Infection is one of the most prevalent and dangerous consequences following ACLR with an incidence of 0.14% to 1.70% according to studies5,6,7,8.

Currently, the main treatment method for patients with infection after ACLR is arthroscopic synovial irrigation and debridement (I&D) combined with systemic antibiotic therapy. However, there is yet to be a consensus on the detailed treatment methods, and it is still unknown as to whether the graft removal is necessary when the infection is severe. Hence, the aim of this study was to analyse the clinical course of this disease and evaluate the possibility of a treatment regimen based on the essential treatment for infection after ACLR, the infection control and the graft retention. Our treatment approach provides recommendations for standardized clinical management. Overall, we introduced the diagnostic criteria for patients with knee infection after ACLR, the typical bacterial profile and clinical treatment plan and the entire process of postoperative rehabilitation.

Methods

Study eligibility

The design of this retrospective cohort study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (Approval No: KY2021-178). Since this study was a retrospective study, the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University exempted patients’ informed consent. We confirmed that all of the methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines. During the study period, all of the adult patients (> 18 years) who underwent primary arthroscopic ACLR at the Department of Joint and Sports Medicine of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University from January 2010 to January 2022 provided signed informed consent for this study.

Identification of patients complicated with infection

We selected 1500 patients who experienced infection after ACLR between January 2010 and January 2022 according to the HIS system for this retrospective study. We collected data on age and sex, as well as findings from laboratory investigations for these patients. The inclusion criteria were as follows. (1) The patient was diagnosed with ACL injury or rupture. (2) The patient underwent anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The exclusion criteria were as follows. (1) Patients with ACLR postoperative knee injury. (2) Infection of other parts of the body or system. (3) Patients who were taking immunosuppressive drugs or hormones for a long period of time. (4) Patients with concomitant immune diseases and other noncomplicated injuries within the knee joint. (5) Patients with severe primary diseases, such as those of the heart, brain, liver, kidney, or haematopoietic system, as well as poor overall condition.

Of the 1500 patients, 20 were infected after ACLR surgery. We screened 1500 patients who were diagnosed with postoperative infection of the ACL according to the inclusion criteria. The diagnostic conditions of the infection were as follows: (1) Pain and swelling: patients who experienced significant pain and swelling in the limb after surgery. (2) Limited Mobility: the knee joint exhibited limited flexion and extension. (3) Skin changes: localized increase in skin surface temperature with associated redness. (4) Systemic inflammatory signs: body temperature ≥ 38 °C, chills and general fatigue. (5) Joint puncture: the presence of purulent fluid aspirated via joint puncture. (6) Inflammatory markers: CRP ≥ 20 g/L, white blood cell (WBC) count ≥ 10 × 109/L, and neutrophil percentage ≥ 90%. (7) Microbial evidence: positive bacteria detection after puncture of the knee joint or tendon removal site. The 7th diagnostic criterion is the gold standard for the diagnosis of suppurative arthritis. If there are two or more items in numbers 1–5, laboratory examination and observation of inflammatory indicators are necessary. After screening, 20 patients met the criteria. Table 1 shows the data of infected patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction before the second operation. Patients 1–4 and 10–20 were infected within the joint, and patients 5–9 were infected at the incision of the tendon (Figs. 1, 2).

Procedure for ACLR

All of the patients underwent standardized surgery. In all of the patients, cephalosporin antibiotics were preoperatively administered for antibiotic prophylaxis (30–60 min before surgery) (Group III). Three chief surgeons performed the surgery on all of the patients by using the tibial-femoral tunnel technique for ACLR under arthroscopy. The patients were transferred to the operating room. After anaesthesia, the patient was placed in the supine position, a 1 cm longitudinal incision was made on the medial edge of the patellar tendon, and a 1 cm transverse incision was made on the lateral side. Needle punctures were made to establish anterior medial and anterior lateral approaches to the knee joint, and intra-articular tissues were examined to confirm ACL injury. Subsequently, an oblique incision was made on the medial aspect of the tibial tuberosity to expose the deep fascia, where the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons were identified. The hamstring tendon (HT) was harvested by dissecting surrounding tissues, after which it was folded, woven into bundles, fixed using a suspension fixation system with fixed loops, and soaked in vancomycin for more than 15 min.

The femoral tunnel was needed to flex the knee joint to 120°; subsequently, the locator was positioned at the anatomical footprint centre of the ACL attachment on the femur, a Kirschner wire was passed through the bone tunnel locator point as a guide wire, the locator was removed, and the lateral femoral condyle was drilled from the medial to the lateral side through the lateral femoral condyle by using a hollow drill bit along the direction of the Kirschner wire to prepare a fine bone tunnel. A guide pin was inserted along the direction of the fine bone tunnel, and a reaming drill was used to drill the corresponding diameter and depth of the coarse bone tunnel.

After bone tunnel preparation, the prepared autologous hamstring tendon graft was pulled into the tunnel by using traction sutures, and the mini titanium plate was flipped to catch on the lateral cortex of the femur by using a flipping wire. Compression screws that were slightly larger than the tunnel diameter were used to fix the graft in the tibial tunnel. Below the tunnel, the autologous graft tail was fixed to the anterior tibia approximately 2 cm from the tunnel exit by using anchor nails.

Finally, we opted to place an intra-articular drainage tube. After evacuating the air from the drainage bottle, the tube was connected without the need for an external negative pressure device. The primary purpose of intra-articular drainage is to reduce haemarthrosis by removing blood and other fluids, which can potentially decrease inflammation-induced swelling and discomfort. Reduced fluid accumulation typically lessens pain, thus allowing for earlier mobilization and potentially quicker recovery of the range of motion. With decreased swelling and pain, rehabilitation can commence sooner, thus hastening recovery.

At the end of the surgery, the drainage tube was inserted through the medial incision at the edge of the patellar tendon and into the suprapatellar pouch, after which it was properly secured. The surgical incision was then closed, followed by the application of a compressive bandage with thick cotton padding and release of the tourniquet. Regular checks were made to ensure the patency of the drainage tube, the adequacy of negative pressure, and proper fixation, thus preventing compression, kinking, or blockage of the tube. Any leakage around the tube was addressed by changing the dressings promptly. The drainage volume and the characteristics of the drained fluid were carefully monitored, and the tube was cautiously removed if the 24-h drainage volume was ≤ 100 ml.

In all of the patients, the average duration of surgery was approximately 2 h, and the average postoperative drainage tube removal time was approximately 48 h. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were postoperatively administered for 3 days, along with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for inflammation and pain relief. Inflammatory markers were reassessed postoperatively, and patients were discharged 14 days later when the inflammatory markers returned to normal.

Treatment of postoperative infection after ACLR

Once the diagnostic criteria were met, treatment was immediately initiated. The infection after ACLR was divided into tendon incision infection and intra-articular infection. There was no apparent systemic inflammation in the patients with tendon incision infections. The main clinical symptoms were non-healing of the tendon donor site; local inflammation; and increased CRP, WBC, ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate), and neutrophil percentage. During the course of antibiotic treatment, our initial choice of antibiotics (vancomycin combined with ampicillin/sulbactam) was based on their broad-spectrum coverage, which is crucial in the empirical phase of treatment wherein specific pathogens have not yet been identified. Oral antibiotics such as rifampicin and quinolones are considered to have excellent bioavailability and bone penetration properties and are critical for treating osteoarticular infections9. As for the treatment time of antibiotics, these studies all show that after 2 weeks of intravenous antibiotics, oral antibiotics are chosen, and the treatment time of antibiotics is at least 4 weeks, and the average treatment time is 5 weeks. The actual situation is judged according to the inflammatory indicators of patients10,11,12,13.

Treatment of tendon incision infection

The main treatment options for 5 patients with tendon incision infection were as follows. (1) Intravenous antibiotics were used after joint puncture (joint fluid culture and routine culture); (2) An admixture of vancomycin and ampicillin/sulbactam was used. (3) Afterwards, we used antibiotic-sensitive drugs for 2 weeks according to the drug sensitivity results after the bacterial culture results were available4,10,11,12,14. Oral antibiotics such as rifampicin and quinolones were considered when the CRP concentration continued to decrease for 5–6 days or when the decrease was significant. The duration of antibiotic treatment was 4 weeks11,12; in some patients, the duration of antibiotic treatment was extended to 6 weeks according to the patient’s clinical situation. (4) A total of 3000 ml of normal saline plus gentamicin was used for continuous negative pressure suction irrigation for 2–3 weeks until the wound was close to healing when antibiotics were used. The specific time frame was dependent on the patient’s recovery.

Treatment of intra-articular infection

The other 15 patients had intra-articular infections, and the main treatment regimen involved a close combination of intravenous antibiotics and arthroscopic surgery.

For antibiotic therapy, the utilized antibiotic regimen was vancomycin plus ampicillin/sulbactam. After the bacterial culture results were obtained, antibiotics sensitive to drugs were selected according to the antibiogram. Oral antibiotics should be taken for at least 2 months, and the specific time frame was adjusted according to the patient’s CRP level, WBC count and other test results.

The surgical treatment methods were as follows: (1) the conventional arthroscopic approach was combined with additional posteromedial/posterolateral or superomedial/superolateral approaches; (2) synovial tissue culture during surgery and culture for at least 14 days, which represents the highest sensitivity index, was performed, and the results were compared with those of the puncture fluid; (3) necrotic and inactive tissues were widely and thoroughly removed, and fibrous tissue and clots were simultaneously removed; (4) the joint cavity was irrigated with an adequate amount of normal saline (10–15 L); (5) fibrin covering the surface of the ligament was gently removed; and (6) if a thickened inflammatory synovium was found during the operation (Fig. 3), it should be excised. However, this procedure may cause additional trauma to the knee joint and increase the risk of postoperative joint fibrosis.

For postoperative treatment, anti-infective therapy with sensitive antibiotics was given intravenously for 2 weeks after surgery. The patient was evaluated after 2 weeks based on the clinical results and biomarker levels. Arthroscopic irrigation and debridement were repeatedly performed if there was a history of joint effusion, increased pain, redness, elevated body temperature, elevated CRP and WBC count or no significant decrease in these parameters. After discharge, the ESR, CRP level, and liver and kidney function were regularly reviewed. The affected limb was fixed with a brace, and weight-free walking combined with appropriate functional exercise was performed.

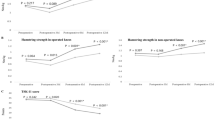

For the rehabilitation program and follow-up, knee flexion and extension exercises were performed twice daily, gradually increasing the flexion angle. The knee can flex to 90 degrees within 2–3 weeks after the removal of the irrigation drainage device and to 120 degrees after 4–5 weeks. Weight-bearing on the affected limb was avoided for the first 4 weeks. Each patient gradually initiated weight-bearing under the protection of a brace in the extension position from 4 to 12 weeks. The brace was removed within 3–6 months for daily activities. Normal physical activity could be resumed starting at 6 months. At the 6-month postoperative follow-up, we recorded the patients’ Lysholm score, CRP level, WBC count, neutrophil percentage, and maximum flexion angle of the knee joint.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. The statistical significance of the data is determined by using the chi-square test (χ2) and the exact t-test. Continuous and normally distributed data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). A t-test was used to compare knee scores and knee motion before and after treatment. P < 0.05 indicated statistically significant difference.

Ethics approval

The design of this retrospective cohort study was granted approval by The Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (Approval No: KY2021-178). We confirm that: 1. The institutional and licensing committee that approved the experiments, including any relevant details. 2. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant named guidelines and regulations. 3. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians. 4. All research involving human research participants are performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Baseline features of the study participants

The study included 800 males (53%) and 700 females (47%) with an average age of 35.5 ± 8.25 years (range: 18–60) at the time of surgery. All of the study subjects were Chinese. For infections after ACLR, 11 (55%) males and 9 (45%) females were selected. None of the patients who underwent simultaneous meniscectomy, meniscus repair, chondroplasty, or other ligament reconstruction procedures had previously undergone surgery. The aggregate rate of infection after ACLR was 1.33% (20/1500). There were statistically significant differences in age between infected patients and noninfected patients (37.2 ± 9.67 vs. 28.4 ± 8.34 years, respectively; P < 0.001). Patients diagnosed with septic arthritis (SA) had a notably greater average BMI (27.34 ± 2.50) than noninfected patients (21.4 ± 3.6; P < 0.0001). Approximately 60% of the SA patients also had diabetes, whereas only 8.3% of the noninfected patients had diabetes (P < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences in sex between the two groups (P > 0.05), thus suggesting that age, BMI, and diabetes mellitus may be associated with post-ACLR infection, whereas sex was not related to infection. Detailed information for both groups is presented in Table 2.

Treatment results of ACLR infection

The main clinical manifestations of patients after ACLR infection were fever (80%), knee pain (100.00%), and limited knee movement. C-reactive protein (CRP) > 50 mmol/L was detected in fifteen patients (75%). All of the patients were treated with antibiotics for an average of 44.5 ± 9.6 days (30–60). Fifteen patients were discharged with intrajoint infection after an average of 1.9 (± 0.8) arthroscopic irrigations and debridements. Five patients with infection of the tendon donor site were treated by using continuous negative pressure suction irrigation until the wound healed. Fortunately, grafts were not removed in any of the 20 patients.

Laboratory results of patients after surgery

Staphylococcus aureus (80%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (10%) and gram-negative bacilli were the pathogenic bacteria detected in 20 patients after ACLR. None of the collected samples yielded fungal, mycobacterial, or polymicrobial growth.

Follow-up results

All of the local and systemic symptoms disappeared, and the range of motion of the knee joint improved after 6 months of outpatient reexamination. The laboratory indicators, such as CRP levels and routine blood tests, returned to normal. The mean Lysholm score was 89.9 (85–96) at the time of follow-up. The anterior drawer test and the pivot-shift test were negative. Nearly all of the patients had no complaints of knee swelling pain or instability, and the maximum range of motion of the knee was greater than 120° (Table 3). The difference in the Lysholm score of the affected knee between treatment before infection and after 6 months of outpatient follow-up was statistically significant (t = 20.78, P < 0.001), and the success rate of the treatment was 100%.

Discussion

The main findings of this study indicate that postoperative infection is a rare complication of ACLR and can be successfully treated through antibiotic therapy combined with arthroscopic irrigation and debridement or negative pressure suction irrigation. In most cases, graft preservation was possible. We determined the clinical cure criteria for postoperative knee joint infection following knee arthroscopic ACL surgery as follows: (1) cessation of all drug treatments and normal body temperature for 2 weeks; (2) disappearance of local symptoms such as redness, swelling, heat, and pain; (3) recovery of WBC count and neutrophil percentage to near-normal levels and a significant decrease or decreasing trend in CRP and ESR (which are difficult to reduce to completely normal levels during hospitalization); and (4) negative bacterial culture results from joint fluid aspiration. Clinical cure can only be determined when all of the abovementioned four criteria are met. For patients with knee joint infection after ACLR, efforts should be made during surgery to preserve the graft as much as possible. The overall postoperative infection rate in our study was 1.33% (20/1500), which is similar to other studies5,6,7,8.

The literature on the risk factors for SA following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) remains inconclusive, which is primarily due to its low incidence. Studies have indicated that an increased incidence of SA post-ACLR is significantly associated with older age, male sex, elevated body mass index (BMI), and diabetes mellitus (DM). Logistic regression analysis further identified increased age, higher BMI, and DM as independent predictors of the occurrence of SA15. Schmitz et al.16 demonstrated that male sex is an independent risk factor for infection, although findings regarding DM are contradictory. A previous study indicated that among 189 diabetic patients, only two (1.1%) developed SA, thus indicating no significant correlation between postoperative infection and diabetes, which may suggest potential bias due to the low prevalence of diabetes in the study population, which was only 0.7%16. However, a meta-analysis of 17 studies involving 141,991 patients demonstrated that male sex and diabetes are independent risk factors for post-ACLR infection, whereas there was no significant association between postoperative infection and age or BMI17. In this study, however, our results suggest that age, BMI, and diabetes may be associated with post-ACLR infection, while sex is not. More research is still needed to confirm the risk factors for postoperative infection in ACLR patients.

There is a question as to what causes postoperative infection in ACLR. There is currently no exact answer to this question. Agarwalla et al.18 reported that there is a correlation between the increase in surgical time for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and the risk of infection. Every additional 15 min of surgery will increase the probability of postoperative infection (relative risk: 1.12). Operative time is an independent risk factor for complications, including surgical site infections, in arthroscopic knee surgery19,20. Another study came to a similar conclusion; specifically, during arthroscopic knee surgery, the irrigation fluid on surgical covers is prone to bacterial contamination that escalates over time. This contamination, which primarily originates from microorganisms constituting the normal skin flora, suggests a potential source of surgical site infections21. These studies collectively indicate that prolonged surgical duration may be associated with postoperative infections in ACLR, thus highlighting the need to maximize surgical efficiency16. We believe that this may be related to tendon incision infection in our study. Some scholars have also suggested that the risk of infection is related to the length of the graft22. Given the severity of septic arthritis, it is crucial to prevent postoperative infection following ACLR of the knee joint.

Research by Naendrup et al.23 suggested that incorporating vancomycin soaking into grafts significantly reduces the incidence of septic arthritis after primary ACL reconstruction (ACLR). Although there appear to be no other differences in clinical outcomes, biomechanical tendon properties, or cartilage integrity between patients with and without vancomycin-soaked grafts, the preventative effect against pyogenic arthritis is noteworthy. Grafts soaked in vancomycin can significantly lower the incidence of septic arthritis following primary ACLR24. Additionally, some studies have indicated that the intraoperative use of vancomycin-impregnated graft preparations during arthroscopic ACL reconstruction is a highly cost-effective prophylactic measure against infection25,26. Therefore, in routine clinical practice, the use of vancomycin-soaked anterior cruciate ligament grafts may represent a safe, economical, simple, and effective method23. We soaked the graft in vancomycin during the initial ACLR surgery. Reports in the literature have shown that soaking an ACL autograft in a 5 mg/ml vancomycin solution can significantly reduce (and even eliminate) infectious arthritis after ACLR. Notably, this strategy is more effective when using autogenous tendon grafts5,27,28. Therefore, we recommend immersing the transplant in vancomycin for at least 15 min during the initial ACLR surgery.

Due to the fact that the majority of bacteria causing infections after ACLR are Staphylococcus aureus (80%), sensitive drugs should be used when selecting antibiotics before bacterial culture is confirmed. Staphylococcus aureus is a resilient bacterium that possesses several virulence factors that contribute to its pathogenesis. Capsular polysaccharides, cell wall teichoic acid and lipopolysaccharides, surface and secreted proteins, and multiple potent exotoxins are worth mentioning. We intravenously administered a combination of vancomycin and sulbactam, along with oral levofloxacin and rifampicin for a 6-week treatment course10. In addition to the use of standard intravenous antibiotics, intraoperative application of vancomycin powder can significantly reduce the infection rate. Vancomycin powder application is a simple approach that can prevent patients from undergoing a second surgery in ACLR28,29,30. The main cause of knee cartilage destruction in patients with purulent arthritis is the inflammatory response. As the primary clinical manifestation of inflammation is pain, all of the patients in our study were orally administered nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which can reduce inflammation and alleviate postoperative pain.

For patients who develop knee joint infections after ACLR, engagement in active treatment and rehabilitation exercises results in no discernible difference in knee joint function compared to patients who undergo ACLR without infection during the same time period31. Septic arthritis after arthroscopic knee ligament reconstruction is a serious complication; therefore, we recommend preservation of the graft under arthroscopy, which is determinable during surgery and can be preserved in most cases11,32,33. All transplants of the patients in this group were preserved. The employed therapy provided an easily achievable and standardized treatment plan, which allowed patients to return to the standard ACLR rehabilitation process. Satisfactory results were achieved in terms of transplant preservation, knee joint stability and functional integrity. There were no cases of knee joint infection recurrence during postoperative follow-up. At the last follow-up, all of the patients had recovered from good knee joint function and had no complaints of knee joint swelling or instability. The motion range of the knee joint exceeded 120° for nearly all of the patients. For patients with knee joint infection after arthroscopic ACLR, early diagnosis should be made, and broad-spectrum antibiotics should be used as soon as possible depending on the patient’s specific condition. The standard procedure involves antibiotics sensitive to bacterial culture with surgical debridement. The surgeon should attempt to preserve the graft, followed by gradual knee joint function training28,34,35.

The main choice for graft selection during surgery is typically the hamstring tendon, which may be another factor in postoperative infection after ACLR. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that compared to the use of the hamstring tendon and all other types of grafts, the use of bone patellar tendon bone (BPTB) autografts significantly reduces the incidence of infection after ACLR36. The results of this meta-analysis are consistent with recent specialized studies on infection after ACLR. In a multicentre study of 2198 patients with ACLR, Brophy et al.35 demonstrated a significant increase in infection risk when using autogenous hamstring grafts. In a study of 10,626 patients with ACLR, Maletis et al.19 confirmed that the risk of deep infection is 8.2 times greater in autografted hamstring tendons than in BPTB autografts. This systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that the use of BPTB autografts significantly reduces the risk of infection compared to the use of autograft hamstring tendons after ACLR, and the incidence of infection associated with the use of autografts was not significantly different from that associated with the use of allografts. The reasons for the increased risk of infection with autografted hamstring tendons compared to BPTB autografts should be investigated, as should the potential mitigation measures36. Some scholars have also suggested that the risk of infection is related to the length of the graft. Relatively short hamstring muscle grafts can increase the amount of suture material used in the knee joint, which increases the risk of foreign body infection and may lead to inflammatory reactions36. However, the use of BPTB grafts can lead to postoperative anterior knee pain, including pain at the donor site and patellofemoral joint, as well as difficulty and discomfort when performing kneeling activities. The second disadvantage is that the patellar tendon itself belongs to the extensor mechanism; thus, the removal of a portion of it can cause postoperative extensor mechanism disorders, such as limited extension and weakness of the quadriceps muscle. Therefore, the selection of graft material is an issue that surgeons should carefully consider37,38.

The addition of corticosteroids to antibiotics for suppressing excessive immune reactions may be an effective treatment method. A randomized clinical trial evaluated the efficacy of dexamethasone in treating septic arthritis and demonstrated that short-term, low-dose dexamethasone combined with antibiotics can shorten the course of the disease, alleviate bacterial infection-induced damage to the joint, and improve joint function. This combination therapy may be beneficial for patients with post-ACLR joint infections22. Due to differing treatment philosophies for infections following ACL reconstruction versus joint replacement surgery, joint replacement surgery requires as much preservation of the internal structures of the knee as possible, whereas ACLR primarily focuses on preserving the graft. Therefore, patients with purulent arthritis after ACLR can undergo glucocorticoid and antibiotic treatment for quick recovery. Dexamethasone has not yet been used in surgery, and its efficacy still needs further experimental exploration.

Nevertheless, there were several limitations to consider in this study. (1) Patients with different types of ACL injuries exhibited heterogeneity in the study population, which may bias the results. (2) The cases that we collected did not include ACL injuries combined with meniscal injuries. We cannot prove whether coinjuries are more susceptible to infection. (3) The overall number of cases was relatively small, with only twenty infection cases included in this study. With such a limited number of participants, there is an increased risk of selection bias. This retrospective study is subject to potential biases, including missing data bias and confounding bias. Data loss may have occurred, thus potentially leading to biased interpretations of the study results. Furthermore, failure to control for all of the relevant confounding variables could result in misinterpretations of the outcomes. However, these biases are commonly encountered in retrospective studies, and we believe that these potential biases do not affect the accuracy of our findings. (4) In our study, patients recovered well postoperatively, and the grafts were found to be intact during arthroscopic examination. The grafts were not removed, which does not prove that the grafts are not potential sources of infection. We will continue to conduct in-depth research in the next step of this research, with a main focus on the following aspects: (a) whether vancomycin or third-generation cephalosporins are more effective in combating infections and whether using drugs specifically targeting Staphylococcus aureus can help patients to recover faster; (b) further exploration of the possibility of other factors causing infection after ACLR, such as body weight and BMI, as well as the possibility of other complications, such as diabetes, causing infection and exploring treatment strategies for these special cases; and (c) we believe that even with chronic recurrent surgical site infections, a good prognosis can also be achieved through graft preservation. We will confirm this scenario through analyses of more cases. We plan to conduct a multicentre study to increase the sample size and extend the follow-up period. This will enable us to observe the long-term effects and to develop more effective and rapid treatment strategies for restoring knee function in patients with postoperative infections following ACLR.

Conclusion

Although the incidence of infection after ACLR is low, the consequences are severe. Therefore, attention should be given to details such as soaking the ligament in vancomycin and selecting the graft for ACLR. In the event of an infection, immediate joint fluid bacterial culture is necessary, followed by tailored antibiotic therapy and arthroscopic debridement based on the specific circumstances of the infection. Early diagnosis, appropriate treatment and rehabilitation are crucial. These steps are key to restoring knee function and preventing further damage to the joint.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due Ethical reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SA:

-

Septic arthritis

- ACLR:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ACL:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament

- I&D:

-

Irrigation and debridement

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- NSAIDs:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

References

Babalola, O. R., Babalola, A. A. & Alatishe, K. A. Approaches to septic arthritis of the knee post anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 16, 274–283 (2023).

Bosco, F. et al. Advancements in anterior cruciate ligament repair—Current state of the art. Surgeries 5, 234–247 (2024).

Li, Z. Efficacy of repair for ACL injury: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Sports Med. 43, 1071–1083 (2022).

Greenberg, D. D., Robertson, M., Vallurupalli, S., White, R. A. & Allen, W. C. Allograft compared with autograft infection rates in primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 92, 2402–2408 (2010).

Torres-Claramunt, R. et al. Managing septic arthritis after knee ligament reconstruction. Int. Orthop. 40, 607–614 (2015).

Tjoumakaris, F. P., Herz-Brown, A. L., Bowers, A. L., Sennett, B. J. & Bernstein, J. Complications in brief: Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 470, 630–636 (2012).

Busam, M. L., Provencher, M. T. & Bach, B. R. Complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with bone-patellar tendon-bone constructs. Am. J. Sports Med. 36, 379–394 (2008).

Richter, D. L., Werner, B. C. & Miller, M. D. Surgical pearls in revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery: When must I stage?. Clin. Sports Med. 36, 173–187 (2017).

Pérez-Prieto, D. et al. Infections after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Which antibiotic after arthroscopic debridement?. J. Knee Surg. 30, 309–313 (2016).

Kim, S. J., Postigo, R., Koo, S. & Kim, J. H. Infection after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthopedics 37, 477–484 (2014).

Otchwemah, R. et al. Effective graft preservation by following a standard protocol for the treatment of knee joint infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J. Knee Surg. 32, 1111–1120 (2018).

Themessl, A. et al. Patients return to sports and to work after successful treatment of septic arthritis following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 30, 1871–1879 (2022).

Schuster, P. et al. Septic arthritis after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Evaluation of an arthroscopic graft-retaining treatment protocol. Am. J. Sports Med. 43(12), 3005–3012 (2015).

Schuster, P. et al. Septic arthritis after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am. J. Sports Med. 43, 3005–3012 (2015).

El-Kady, R. A. E. H. & ElGuindy, A. M. F. Septic arthritis complicating arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: An experience from a tertiary-care hospital. Infect. Drug Resist. 15, 3779–3789 (2022).

Schmitz, J. K. et al. Risk factors for septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A nationwide analysis of 26,014 ACL reconstructions. Am. J. Sports Med. 49, 1769–1776 (2021).

Zhang, L., Yang, R., Mao, Y. & Fu, W. A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for an infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 11, 23259671231200824 (2023).

Agarwalla, A. et al. Effect of operative time on short-term adverse events after isolated anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 7, 2325967118825453 (2019).

Maletis, G. B. et al. Incidence of postoperative anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction infections. Am. J. Sports Med. 41, 1780–1785 (2013).

Gowd, A. K. et al. Operative time as an independent and modifiable risk factor for short-term complications after knee arthroscopy. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 35, 2089–2098 (2019).

Bartek, B. et al. Bacterial contamination of irrigation fluid and suture material during ACL reconstruction and meniscus surgery: Low infection rate despite increasing contamination over surgery time. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 30, 246–252 (2022).

Binnet, M. S. & Başarir, K. Risk and outcome of infection after different arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction techniques. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 23, 862–868 (2007).

Naendrup, J. H. et al. Vancomycin-soaking of the graft reduces the incidence of septic arthritis following ACL reconstruction: Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 1005–1013 (2019).

Schuster, P. et al. Soaking of the graft in vancomycin dramatically reduces the incidence of postoperative septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 2587–2591 (2020).

Truong, A. P., Pérez-Prieto, D., Byrnes, J., Monllau, J. C. & Vertullo, C. J. Vancomycin soaking is highly cost-effective in primary ACLR infection prevention: A cost-effectiveness study. Am. J. Sports Med. 50, 922–931 (2022).

Ruelos, V. C. B. et al. Vancomycin presoaking of anterior cruciate ligament tendon grafts is highly cost-effective for preventing infection. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 37, 3152–3156 (2021).

Banios, K. et al. Soaking of autografts with vancomycin is highly effective on preventing postoperative septic arthritis in patients undergoing ACL reconstruction with hamstrings autografts. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 29, 876–880 (2021).

Wan, K. H. M., Tang, S. P. K., Lee, R. H. L., Wong, K. K. & Wong, K. K. The use of vancomycin-soaked wrapping of hamstring grafts to reduce the risk of infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: an early experience in a district general hospital. Asia-Pac. J. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rehabil. Technol. 22, 10–14 (2020).

Antoci, V., Adams, C. S., Hickok, N. J., Shapiro, I. M. & Parvizi, J. Antibiotics for local delivery systems cause skeletal cell toxicity in vitro. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 462, 200–206 (2007).

Wang, C., Lee, Y. H. D. & Siebold, R. Recommendations for the management of septic arthritis after ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 22, 2136–2144 (2013).

Mishra, P. et al. Incidence, management and outcome assessment of post operative infection following single bundle and double bundle ACL reconstruction. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 9, 167–171 (2018).

Windhamre, H. B., Mikkelsen, C., Forssblad, M. & Willberg, L. Postoperative septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Does it affect the outcome? A retrospective controlled study. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 30, 1100–1109 (2014).

Torres-Claramunt, R. et al. Knee joint infection after ACL reconstruction: Prevalence, management and functional outcomes. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 21, 2844–2849 (2012).

Saper, M., Stephenson, K. & Heisey, M. Arthroscopic irrigation and debridement in the treatment of septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 30, 747–754 (2014).

Bansal, A., Lamplot, J. D., VandenBerg, J. & Brophy, R. H. Meta-analysis of the risk of infections after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction by graft type. Am. J. Sports Med. 46, 1500–1508 (2017).

Brophy, R. H. et al. Factors associated with infection following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 97, 450–454 (2015).

Bosco, F., Giustra, F., Masoni, V., et al. Combining an anterolateral complex procedure with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction reduces the graft reinjury rate and improves clinical outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Sports Med. Published online February 14, 2024.

Hart, D. et al. Biomechanics of hamstring tendon, quadriceps tendon, and bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A cadaveric study. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 33(4), 1067–1074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-022-03247-6 (2023).

Funding

This study was supported by a dual professor cooperation program from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. This study was supported by the National Orthopaedic and Exercise Rehabilitation Clinical Medical Research Center (Grant No. China: 2021-NCRC-CXJJ-ZH-11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.K.M. and J.R.G. write the main article. S.C.L and S.C. Conducte research. C.L. Collected the data. Y.Q. give support. C.X. editing the language and tables. X.N.X., J.P.Y., R.W. Assisted the research. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Y., Guo, J., Lv, S. et al. Standardized treatment of infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sci Rep 14, 22332 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65546-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65546-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Optimizing nursing services for orthopaedic trauma patients using SERVQUAL and Kano models

Scientific Reports (2025)