Abstract

We aimed to identify the clinical subtypes in individuals starting long-term care in Japan and examined their association with prognoses. Using linked medical insurance claims data and survey data for care-need certification in a large city, we identified participants who started long-term care. Grouping them based on 22 diseases recorded in the past 6 months using fuzzy c-means clustering, we examined the longitudinal association between clusters and death or care-need level deterioration within 2 years. We analyzed 4,648 participants (median age 83 [interquartile range 78–88] years, female 60.4%) between October 2014 and March 2019 and categorized them into (i) musculoskeletal and sensory, (ii) cardiac, (iii) neurological, (iv) respiratory and cancer, (v) insulin-dependent diabetes, and (vi) unspecified subtypes. The results of clustering were replicated in another city. Compared with the musculoskeletal and sensory subtype, the adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) for death was 1.22 (1.05–1.42), 1.81 (1.54–2.13), and 1.21 (1.00–1.46) for the cardiac, respiratory and cancer, and insulin-dependent diabetes subtypes, respectively. The care-need levels more likely worsened in the cardiac, respiratory and cancer, and unspecified subtypes than in the musculoskeletal and sensory subtype. In conclusion, distinct clinical subtypes exist among individuals initiating long-term care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increase in global aging, the population of older adults requiring long-term care is increasing. In response, several countries, including Japan, South Korea, and Germany, have established public long-term care systems1. Japan introduced its public long-term care insurance system in 2000, allowing individuals aged ≥ 65 years, as well as those aged 40–64 years with specified diseases (e.g., stroke), to access long-term care services at home or in facilities when needed2,3.

Older adults requiring long-term care tend to have various diseases. In a study by Iwagami et al., which utilized linked medical and long-term care insurance claims data, numerous medical conditions were found to be significantly associated with the initiation of long-term care, with varying degrees of association4. The largest odds ratio in the case–control study was found for femoral fractures, followed by dementia, pneumonia, hemorrhagic stroke, and Parkinson’s disease4. However, the study examined only the independent association between each disease and the initiation of long-term care and did not evaluate the patterns of multiple diseases or multimorbidity.

Older patients often present with multiple underlying diseases. Mitsutake et al. revealed that approximately 80% of older patients (aged ≥ 75 years) in Tokyo had two or more comorbidities, with several patterns identified5. However, this study did not specifically address individuals requiring long-term care, and it did not investigate the association between disease patterns and patient prognosis. Some researchers have examined the association between clinical subtypes and prognosis in the general older population using machine learning methods6,7. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated this association among older adults starting long-term care, a growing population worldwide.

Applying an unsupervised machine-learning approach (to prevent preconceptions) to linked medical and long-term care datasets, this study aimed to identify the clinical subtypes of older adults starting long-term care and examine the longitudinal associations between different clinical subtypes and prognoses.

Results

Study participants and their comorbidities

In Tsukuba City, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan, among the 4831 participants meeting the inclusion criteria, we excluded 151 aged < 65 years and 32 who died before starting long-term care services; the remaining 4648 participants were included in the analysis. The median age of the participants was 83 (interquartile range [IQR], 78–88) years, and 60.4% were females. The median number of comorbidities was 4 (IQR, 3–6), and 4118 (88.6%) participants had two or more comorbidities. The most frequently observed disease in the final sample was dorsopathies (n = 2777, 59.8%), followed by other arthropathies (n = 1840, 39.6%). The relationship between each disease is shown in Fig. 1.

Network plot for each comorbidity in the overall population. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Other LRT diseases other lower respiratory tract diseases. Each circle size represents the number of participants with that disease. The width of each connected line represents the number of participants with both the diseases.

Clustering the study participants based on the comorbidities

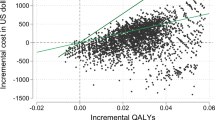

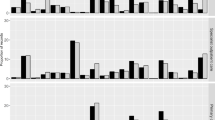

For fuzzy c-means clustering, we determined that the optimal number of clusters was six according to the results of the elbow method and the Xie-Beni index (see Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Table S1 online). We identified six clinical subtypes and named them musculoskeletal and sensory (n = 1025, 22.1%), cardiac (n = 729, 15.7%), neurological (n = 765, 16.5%), respiratory and cancer (n = 421, 9.1%), insulin-dependent diabetes (n = 371, 8.0%), and unspecified (n = 1337, 28.8%) according to the diseases included in each subtype (Fig. 2). The baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

In the validation analysis in another city (Sammu City, Chiba Prefecture, Japan), the results of clustering were generally similar: comorbidities of 1,628 participants were classified into musculoskeletal and sensory (n = 335, 20.6%), cardiac (n = 196, 12.0%), neurological (n = 224, 13.8%), respiratory and cancer (n = 282, 17.3%), insulin-dependent diabetes (n = 208, 12.8%), and unspecified subtypes (n = 383, 23.5%) (see Supplementary Fig. S2 online).

Longitudinal analysis between the clinical subtypes and death

Table 2 shows the results of the cohort analysis in Tsukuba City. After a median follow-up of 36.8 (IQR 24.8–52.5) months, 1879 deaths occurred. Figure 3 shows Kaplan–Meier survival curves for overall survival across clinical subtypes, whereas Supplementary Fig. S3 shows the Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard estimates, which roughly support the proportional hazards assumptions. Compared with musculoskeletal and sensory subtype, the adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval [CI]) for death was 1.22 (1.05–1.42), 0.86 (0.74–1.01), 1.81 (1.54–2.13), 1.21 (1.00–1.46), and 0.90 (0.78–1.03) for the cardiac, neurological, respiratory and cancer, insulin-dependent diabetes, and unspecified subtypes, respectively (Table 2).

Longitudinal analysis between the clinical subtypes and deterioration of care-need levels within 2 years

Table 3 shows the change in care-need levels within 2 years for each subtype. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, and the initial care-need level, the cardiac (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.39, 95% CI 1.08–1.80), respiratory and cancer (aOR 2.29, 95% CI 1.67–3.15), and unspecified subtypes (aOR 1.47, 95% CI 1.18–1.83) were significantly associated with an increased risk of care-need level deterioration (including death) within 2 years compared with the musculoskeletal and sensory subtype. In the first sensitivity analysis, which excluded those with no reassessment of care-need levels, the results were generally similar to those in the primary analysis. In both the main analysis and the first sensitivity analysis which accounted for death, the aOR of each subtype, especially for the cardiac subtype, was influenced and possibly mediated by the number of comorbidities. In the second sensitivity analysis excluding those with death, the cardiac (aOR 1.45, 95% CI 1.04–2.02), neurological (aOR 1.66, 95% CI 1.23–2.25), respiratory and cancer (aOR 1.63, 95% CI 1.05–2.53) and unspecified (aOR 2.04, 95% CI 1.57–2.67) subtypes were significantly associated with an increased risk of care-need level deterioration (excluding death), indicating that the results in the primary analysis for the neurological subtype was largely influenced by death.

Discussion

In this study, using unsupervised machine learning, we identified six distinct clinical subtypes among individuals aged ≥ 65 years who started long-term care in a city in Japan. The results of clustering were similar to that in another city. In the longitudinal analysis, individuals with cardiac, respiratory and cancer, and insulin-dependent diabetes subtypes had a significantly higher risk of death than those with the musculoskeletal and sensory subtype, independent of age, sex, and initial care-need levels. Furthermore, individuals with cardiac, respiratory and cancer, and unspecified subtypes were at a higher risk of deterioration of the care-need level within 2 years than those with the musculoskeletal and sensory subtype.

Clustering is considered an active method of grouping data into many collections or clusters according to the similarities in data point features and characteristics8. By employing machine learning-based clustering methods without predefined hypotheses, we can expand our understanding of the characteristics inherent within a heterogeneous group beyond our initial perceptions9. Several studies have applied clustering methods to categorize individuals with a disease or condition into more homogenous subgroups. For example, Cohen et al. identified three clinical phenogroups of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and their different responses to spironolactone10. Ahlqvist et al. identified five replicable clusters among patients with diabetes showcasing different disease progressions and risks of diabetic complications11.

The older population is inherently diverse, encompassing a spectrum of comorbidities5 and socioeconomic backgrounds. Stratifying a heterogeneous group of individuals requiring long-term care into distinct subtypes can be beneficial for precisely understanding their characteristics and exploring more tailored and effective care approaches. Previous studies using clustering methods revealed that some clinical subtypes of chronic conditions in older adults have synergistic adverse effects6,7,12. In a Stockholm-based study, using a fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm, Tazzeo et al. found that older adults with multimorbidity, characterized by metabolic and sleep disorder patterns; cardiovascular, anemia, and dementia patterns; and psychiatric disease patterns were associated more with incident physical frailty in 6 years7. Marengoni et al. found that those with cardiovascular, anemia, and dementia patterns were associated with an increased risk of institutionalization in 6 years compared with those with an unspecified pattern12. Notably, these findings exhibit substantial differences from the outcomes of this study, possibly due to the different characteristics of the study population in different countries and/or the different factors used for clustering. In contrast, Ibarra-Castillo et al., in a study conducted in Barcelona using a k-means clustering algorithm, delineated six multimorbidity patterns and their associations with mortality6. Their patterns encompassed musculoskeletal, endocrine-metabolic, neurological, cardiovascular, digestive-respiratory (in men only), digestive (in women only), and nonspecific patterns. Compared with the musculoskeletal pattern, the other patterns were associated with a significantly higher risk of death. These patterns are similar to those observed in this study.

In our opinion, some potential reasons contributing to each clinical subtype showing different outcomes could be the types and number of comorbidities involved. The three leading causes of death in Japan in 2022 were malignancy, heart disease, and senility13. This may explain why the cardiac subtype and the respiratory and cancer subtype had worse mortality outcomes. People with insulin-dependent diabetes may have had longer periods of morbidity and more complications than in people with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. This may explain why the insulin-dependent diabetes subtype had worse mortality. Regarding the deterioration of care-need levels within 2 years, diseases that could progress and affect activities of daily living in the relatively short period (e.g. heart disease and malignancy) may have influenced the results. The neurological subtype with the same prevalence of dementia as in the unspecified subtype had a better outcome, despite having more comorbidities. Therefore, we considered that dementia in the unspecified subtype was not associated with a negative outcome and that there might be another unmeasured risk factor affecting the unspecified subtype.

This study holds several clinical and research implications. In clinical settings, the findings suggest that medical and long-term care staff should be more conscious of the clinical subtypes among long-term care users. This information can be used when engaging in shared decision-making with patients and their family members or caregivers, facilitating better preparation for prognostic considerations. In the realm of research, the current study results can be used for classification or restriction of the study population in future interventional studies to examine the effectiveness of specific interventions. While certain services have demonstrated efficacy in individuals certified as requiring support to prevent the deterioration of care-need levels14,15, the study suggests that these services may also prove effective in specific subtypes of individuals certified as needing care. Ultimately, medical and long-term care services should be tailored according to care-need levels and clinical subtypes16,17.

This study had some limitations. First, this study was conducted in one city in Japan, and a validation study was conducted in another city. Although the clustering results were generally similar between the two cities, generalizability may still be a concern. Thus, the finding should be replicated in other areas of Japan, as well as in other countries. Second, misclassification of each of the 22 diseases was possible mainly because the disease status was based on the recorded International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes in the medical claims. The results of this study should be replicated in another study with primary data collection, in which the diagnosis is ensured by the responsible physicians. Third, in any studies using clustering, to name each cluster could be considered subjective. This may be true in the present study, and different researchers could name each cluster differently based on their clinical experience. In addition, we conducted this study based solely on 22 diseases listed by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, which did not include other diseases such as psychiatric disorders and anemia. Considering the potential inclusion of psychiatric disorders7,18 in the identified "unspecified" subtype, further research, including potential diseases other than those in this study, is necessary to clarify the characteristics of unspecified subtypes in more detail. Additionally, in the longitudinal analysis, we adjusted for age, sex, and the initial care-need level as potential confounding factors; however, there may be other (unmeasured) confounding factors, such as socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

We identified novel clinical subtypes of older adults starting long-term care in Japan and found that their association with prognosis differed between the subtypes. The study findings indicated long-term care strategies and informed consent from patients and their family members can be tailored according to the clinical subtypes.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted both cross-sectional (for clustering at baseline) and longitudinal analyses in a cohort study (for examining the association between clinical subtypes and all-cause mortality and deterioration of care-need levels) using linked medical insurance claims data and survey data for care-need certification in Tsukuba City in Japan (“main analysis”). In addition, we examined whether our clustering approach was replicable in Sammu City in Japan (“validation analysis”).

Ethical approval

This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved and informed consent was waived due to the anonymous nature of the data by the Ethics Committee, Institute of Medicine, University of Tsukuba (approval number: 1445-14).

Data source

In Japan, each city maintains medical claims data within the Late-stage Elderly Health System (for those aged ≥ 75 years), National Health Insurance system (for those aged < 75 years), and long-term care certification data. Through a joint research contract, we requested Tsukuba city and Sammu city to provide their data. Tsukuba City's data, with its larger sample size, were considered the derivative sample. Sammu City's data served as the validating sample.

For the main analysis, medical claims data (April 2014 to March 2019), survey data for care-need certification (February 2012 to June 2019), and insurance registration data (October 2014 to March 2021) of enrollees of the Late-stage Elderly Health System or National Health Insurance were obtained from the municipal government of Tsukuba City, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan. Tsukuba City is a large region with a population of 240,383 people, including 46,613 (19.4%) people aged ≥ 65 years19.

For the validation analysis, medical claims data (May 2012 to October 2016) and survey data for care-need certification (May 2012 to October 2016) of enrollees of the Late-stage Elderly Health System or National Health Insurance were obtained from the municipal government in Sammu City, Chiba Prefecture, Japan. The city has a population of 48,444, including 17,329 (35.8%) people aged ≥ 65 years20. We conducted only the cross-sectional analysis in Sammu City because the follow-up data were not sufficiently available.

The details of the Japanese medical and long-term care insurance claims data are described elsewhere21,22,23. Briefly, the medical insurance claims include medical service fees, dates of receiving medical services, diseases according to the ICD-10 codes, tests conducted, and drugs prescribed. Under the long-term care insurance system, people are certified through a standardized process involving an assessment of physical and cognitive functions24 and are categorized into seven grades, as follows: support levels 1 and 2 and care levels from 1 to 5, which are well correlated with the Barthel Index (r = − 0.70)25. They receive periodic reassessments of care-need levels, with intervals ranging from 3 to 24 months during our study period26.

We integrated the medical insurance claims data and survey data for care-need certification and the insurance registration data in the case of Tsukuba City, using the pseudo-ID provided by the municipality.

Study population

In Tsukuba City, we identified people receiving the survey for long-term care needs certification for the first time between October 2014 (ensuring a 6-month look-back period after April 2014 for defining comorbidities from medical claims) and March 2019 (see Supplementary Fig. S4 online). The 6-month look-back period was in line with that in our previous study4, wherein we assumed that diagnoses associated with the long-term care incidence would be recorded within 6 months before long-term care certification in the Japanese healthcare system. In this study, we included those with care levels ranging from 1 to 5, as individuals with support levels often do not require actual long-term care and instead receive preventive care to forestall the need for long-term care. We excluded individuals aged < 65 years and those who died before starting the actual long-term care services.

In Sammu City, for the validation analysis, we identified the participants between May 2013 and October 2016 and applied the same exclusion criteria.

Exposures (factors used for clustering)

According to the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare in the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions in Japan, 22 diseases are considered to potentially affect the initiation of long-term care4. The list includes hemorrhagic stroke, ischemic stroke, other cerebrovascular diseases, ischemic heart disease, arrhythmia, heart failure, other cardiac diseases, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, other lower respiratory tract diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, other arthropathies, dorsopathies, dementia, Parkinson's disease, insulin-dependent diabetes, non-insulin-dependent diabetes, visual impairment, hearing impairment, femur fractures, and other fractures.

We defined the presence or absence of each of the 22 diseases, which were recorded in medical claims during the past 6 months before the certification of long-term care (including the same month when the long-term care was certified). We utilized the ICD-10 codes used in previous studies (see Supplementary Table S2 online)4.

Outcomes

In the cohort analysis in Tsukuba City, the outcomes of interest were all-cause mortality and deterioration of care need levels within 2 years. Data on deaths were obtained from insurance registration, a source theoretically capable of capturing all fatalities up to March 2021. Information on care need levels was derived from the survey data for care-need certification. Specifically, we retrieved the certified care-need levels of participants at or closest to the time point 2 years (i.e., 24 months) from the date of initial certification. Our decision of having a 2-year follow-up period was due to the fact the participants starting that long-term care should have had received periodic reassessments of care-need levels at least once in 24 months during our study period, in the Japanese long-term care system26. In the primary analysis, deterioration of care-need levels was defined as an increase in the level of the latest certification compared with the initial level, or death within 24 months.

Statistical analyses

We summarized the characteristics of the study participants using frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables and medians (IQRs) for continuous variables. The prevalence of each disease and the number of comorbidities (among 22 comorbidities) per person were calculated. We constructed a network plot to identify the relationship between each comorbidity.

For clustering, after conducting dimensionality reduction through multiple correspondence analysis using the “FactoMineR” package of R, we employed a fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm using the “e1071” package of R, allowing individuals to belong to more than one cluster. We employed the elbow method and the Xie-Beni index (optimal when presenting low values)27 to obtain the optimal cluster number, with various cluster numbers tested. We repeated the fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm 100 times to account for the random nature of the cluster solutions, and an average outcome was generated. Participants were assigned to the cluster with the highest membership probability. The observed/expected ratios of diseases and disease exclusivity were used to describe the disease patterns of the clusters7,28. Observed/expected ratios were calculated by dividing the disease prevalence in the cluster by the disease prevalence in the overall population. Disease exclusivity was calculated as the number of participants with a specific disease in a cluster divided by the total number of individuals with that disease. Clusters were characterized based on diseases with an exclusivity of ≥ 25% or an observed/expected ratio of ≥ 27,28. Other basic characteristics of the clusters were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables, such as age and the number of morbidities, and the chi-square test for categorical variables, such as sex and care need levels.

To validate the replicability of the clustering results, in Sammu City, we repeated the same clustering procedure and then compared the results with those obtained from Tsukuba City.

Finally, each cluster was named based on the clustering results of two cities after discussions among the authors who had clinical experience in treating older patients.

In the cohort analysis in Tsukuba City, Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted for death. Additionally, we conducted a Cox proportional hazards analysis for death, with adjustments for age, sex, and initial care-need level. The follow-up continued until the incidence of death, loss to follow-up (defined as removal from the insurance registration for reasons such as moving), or at the end of observation in March 2021. Among the groups except that considered the unspecified subtype, we regarded the group with the largest number of participants as the reference group.

Regarding the deterioration of care-need levels within 2 years, the analysis was restricted to participants who started long-term care before June 2017, so that all the participants (except for those with loss to follow-up) had follow-up information for 2 years. We made a table displaying the number of participants with improved, stable, and deteriorated care-need levels and those with no reassessment, death, or loss to follow-up at 2 years. Excluding those lost to follow-up at 2 years, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted for the deterioration of care-need level (i.e., an increase in the level of the latest certification compared with the initial level or death), with adjustment for age, sex, and the initial care-need level (Model 1) and additionally for the number of comorbidities (Model 2). Care-need level of those with no reassessment was assumed to be unchanged. In the first sensitivity analysis, we excluded those with no reassessment by regarding them as lost to follow-up. In the second sensitivity analysis, individuals with death were further excluded from the analysis, focusing solely on the increase in the latest certification level compared with the initial level.

The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.3.2; R Core Team 2023) and Stata (version 17; StataCorp LLC 2021).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Tsukuba City and Sammu City, Japan, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Tsukuba City and Sammu City.

References

Tamiya, N. et al. Population ageing and wellbeing: Lessons from Japan’s long-term care insurance policy. Lancet 378, 1183–1192 (2011).

Iwagami, M. & Tamiya, N. The long-term care insurance system in Japan: Past, present, and future. JMA J. 2, 67–69 (2019).

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Long-Term Care Insurance System of Japan. (2016). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/care-welfare/care-welfare-elderly/dl/ltcisj_e.pdf. Accessed 1 Jan 2024.

Iwagami, M. et al. Association between recorded medical diagnoses and incidence of long-term care needs certification: A case control study using linked medical and long-term care data in two Japanese cities. Ann. Clin. Epidemiol. 1, 56–68 (2019).

Mitsutake, S., Ishizaki, T., Teramoto, C., Shimizu, S. & Ito, H. Patterns of co-occurrence of chronic disease among older adults in Tokyo, Japan. Prev. Chronic Dis. 16, E11 (2019).

Ibarra-Castillo, C. et al. Survival in relation to multimorbidity patterns in older adults in primary care in Barcelona, Spain (2010–2014): A longitudinal study based on electronic health records. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 72, 185–192 (2018).

Tazzeo, C. et al. Multimorbidity patterns and risk of frailty in older community-dwelling adults: A population-based cohort study. Age Ageing 50, 2183–2191 (2021).

Ezugwu, A. E. et al. A comprehensive survey of clustering algorithms: State-of-the-art machine learning applications, taxonomy, challenges, and future research prospects. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 110, 104743 (2022).

Bi, Q., Goodman, K. E., Kaminsky, J. & Lessler, J. What is machine learning? A primer for the epidemiologist. Am. J. Epidemiol. 188, 2222–2239 (2019).

Cohen, J. B. et al. Clinical phenogroups in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Detailed phenotypes, prognosis, and response to spironolactone. JACC Heart Fail. 8, 172–184 (2020).

Ahlqvist, E. et al. Novel subgroups of adult-onset diabetes and their association with outcomes: A data-driven cluster analysis of six variables. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6, 361–369 (2018).

Marengoni, A. et al. Multimorbidity patterns and 6-year risk of institutionalization in older persons: The role of social formal and informal care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 22, 2184-2189.e1 (2021).

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Vital Statistics in 2022 (in Japanese). (2022). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/geppo/nengai22/dl/gaikyouR4.pdf. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Ito, T. et al. Prevention services via public long-term care insurance can be effective among a specific group of older adults in Japan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 531 (2021).

Maruta, M. et al. Impact of outpatient rehabilitation service in preventing the deterioration of the care-needs level among Japanese older adults availing long-term care insurance: A propensity score matched retrospective study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 1292 (2019).

König, I. R., Fuchs, O., Hansen, G., von Mutius, E. & Kopp, M. V. What is precision medicine?. Eur. Respir. J. 50, 1700391 (2017).

Wang, R. C. & Wang, Z. Precision medicine: Disease subtyping and tailored treatment. Cancers 15, 3837 (2023).

Violán, C. et al. Five-year trajectories of multimorbidity patterns in an elderly Mediterranean population using Hidden Markov Models. Sci. Rep. 10, 16879 (2020).

Japan Medical Analysis Platform. Tsukuba City (in Japanese). https://jmap.jp/cities/detail/city/8220. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

Japan Medical Analysis Platform. Sammu city (in Japanese). https://jmap.jp/cities/detail/city/12237. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. An Outline of the Japanese Medical System. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/iryouhoken/iryouhoken01/dl/01_eng.pdf. Accessed 1 Jan 2024.

Suzuki, A. et al. Factors affecting care-level deterioration among older adults with mild and moderate disabilities in Japan: Evidence from the nationally standardized survey for care-needs certification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 3065 (2022).

Mori, T. et al. The associations of multimorbidity with the sum of annual medical and long-term care expenditures in Japan. BMC Geriatr. 19, 69 (2019).

Kuroda, N. et al. Antipsychotic use and related factors among people with dementia aged 75 years or older in Japan: A comprehensive population-based estimation using medical and long-term care data. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 34, 472–479 (2019).

Matsuda, T. et al. Correlation between the Barthel Index and care need levels in the Japanese long-term care insurance system. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 19, 1186–1187 (2019).

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Regulations Related to Long-Term Care Need Certification (in Japanese). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hukushi_kaigo/kaigo_koureisha/nintei/gaiyo4.html. Accessed 1 Jan 2024.

Ventrano, D. L. et al. Twelve-year clinical trajectories of multimorbidity in a population of older adults. Nat. Commun. 11, 3223 (2020).

Violán, C. et al. Soft clustering using real-world data for the identification of multimorbidity patterns in an elderly population: cross-sectional study in a Mediterranean population. BMJ Open 9, e029594 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid from the Health Care Science Institute Research Grant in 2023, and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Policy Research Grants, Japan (Grant Number: 23AA2003). We thank Editage (http://www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.I., M.I., J.K., and Y.H. planned the study. N.K. and T.I. collected the data. Y.I. and M.I. analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and prepared the figures, tables, and supplementary materials. J.K., Y.H., A.S., T.G., E.W., F.L., and N.T. contributed substantially to the interpretation of results and provided feedback on the main manuscript text. All the authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ito, Y., Iwagami, M., Komiyama, J. et al. Clinical subtypes of older adults starting long-term care in Japan and their association with prognoses: a data-driven cluster analysis. Sci Rep 14, 14911 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65699-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65699-6