Abstract

The core and surface structure and magnetic properties of mechano synthesized LaFeO3 nanoparticles (30–40 nm), their Eu3+-doped (La0.70Eu0.30FeO3), and Eu3+/Cr3+ co-doped (La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3) variants are reported. Doping results in a transition from the O′-type to the O-type distorted structure. Traces of reactants, intermediate phases, and a small amount of Eu2+ ions were detected on the surfaces of the nanoparticles. The nanoparticles consist of antiferromagnetic cores flanked by ferromagnetic shells. The Eu3+ dopant ions enhance the magnetization values relative to those of the pristine nanoparticles and result in magnetic susceptibilities compatible with the presence of Eu3+ van Vleck paramagnetism of spin–orbit coupling constant (λ = 363 cm−1) and a low temperature Curie–Weiss like behavior associated with the minority Eu2+ ions. Anomalous temperature-dependent magnetic hardening due to competing magnetic anisotropy and magnetoelectric coupling effects together with a temperature-dependent dopant-sensitive exchange bias, caused by thermally activated spin reversals at the core of the nanoparticles, were observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The orthorhombically distorted perovskite-related rare-earth orthoferrite materials of the composition (RE)FeO3, where RE is a rare earth ion, are technologically attractive due to their physicochemical properties that render them of potential usage in a host of applications1,2,3,4,5,6,7. One such a material is lanthanum orthoferrite, LaFeO3, that crystallizes in the space group Pbnm (# 62) with lattice constants a = 5.556 Å, b = 5.565 Å and c = 7.862 Å5. The La3+ and Fe3+ ions, respectively, occupy the so-called A sites and the six O2− coordinated octahedral B sites (BO6). Unlike cubic perovskites, where the A sites are 12 O2−-coordinated cuboctahedra (AO12), the orthorhombically distorted (RE)FeO3 (RE = from Pr to Lu) compounds possess 8 O2−-coordinated A sites (AO8). However, in bulk LaFeO3, Marezio et al.8 have shown that the difference between the distances of the La3+ ion to its eighth and ninth nearest O2− neighbors, namely, 2.805 Å and 3.041 Å, respectively, is insignificant. Hence, the A sites in LaFeO3 are considered AO9 polyhedra. The magnetic ordering of the high-spin Fe3+ cations in LaFeO3 results in G-type antiferromagnetism (AFM) which is accompanied by a weak canted ferromagnetic (FM) component. The high Néel temperature (TN) of ~ 740 K reported for the material is a consequence of the strong Fe3+–O2−–Fe3+ superexchange coupling1,9. The other inherent properties of LaFeO3, which are important from an applied viewpoint, include thermal, electrical, magneto-optical, and high chemical stability, in addition to multiferroicity2,4,5,10.

To extend the technological utilization of LaFeO3, some researchers have attempted to modify its properties by producing it either in the form of nanoparticles or by introducing substituents for La3+ and/or Fe3+ cations2,3,4. In this respect, novel magnetic properties, such as magnetic exchange bias (EB), superparamagnetism, and spin glass behavior, have been reported for LaFeO3 nanoparticles of sizes in the 10–60 nm range2,3,9,10,11. Such properties, which are of interest for various applications, including magnetic sensors, spintronics, and data storage devices1,4,6, could be further tuned by single-site cation doping. In connection with this, we note that when soft chemistry methods were used to introduce Na+, Zn2+, Sb3+ or Ce4+ as sole substituents for La3+ in LaFeO3 nanoparticles, the coercivity (Hc) was found to depend on the dopant concentration3,5,11. Doping with single cations such as Na+ and Zn2+ has affected the superparamagnetic behavior of the nanoparticles, as both the blocking and relaxation temperatures were found to decrease3,9. Of interest to us in this paper is the work of Hosseini et al. who reported the use of the sol–gel route to form Eu3+-doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles of the composition La1−xEuxFeO3 (x ≤ 0.15) without elaborating on how Eu3+-doping affects their structural and magnetic properties12. Similarly, the substitution of Fe3+ in LaFeO3 nanoparticles with transition metal (TM) cations has been an active area of research4,6,10. For instance, a spin-glass-like freezing temperature and cluster-spin behavior were reported when Mn3+ and Cr3+ were used as substituents for Fe3+ in LaFeO3 nanoparticles13,14. EB behavior has been reported to be barely noticeable when substituting La3+ cations with Zn2+ in LaFeO3 nanoparticles3,10. Ferromagnetically weak single-domain LaFeO3 nanoparticles with particle size-dependent Hc were reported when Fe3+ ions were partially substituted4 by Ti4+. Recently, we have shown that Ru3+-doping modifies the properties of mechano-synthesized LaFe1−xRuxO3 nanoparticles, resulting in Jahn–Teller-like distortion, a size-dependent hyperfine magnetic field, and a monotonic decrease in the optical band gap with increasing Ru3+ content6. In addition, the structure of the mechano-synthesized LaFe1−xRuxO3 nanoparticles was found to index to the O′-type perovskite structure with the lattice parameters related according to c/\(\sqrt 2\) < a < b as opposed to the O-type perovskite structure of bulk LaFeO3 wherein a < c/\(\sqrt 2\) < b6. These modifications are associated with the route of mechano-synthesis, which is known to form nanoparticles with a non-uniform core–shell structure in which the exchange interactions between the inner crystalline core and an outer disordered or amorphous shell often result in novel physical properties15,16. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have been devoted to the case in which both La3+ and Fe3+ cations in LaFeO3 nanoparticles are concurrently substituted17,18,19. Such co-doping was found to lead to notable changes in the magnetic and ferroelectric properties, as was shown for the La0.8Sr0.2Fe1−xCuxO3, La0.9Dy0.1Fe0.9Ti0.1O3 and La1−xDyxFe1−yMnyO3 nanoparticles. In a previous study on mechano-synthesized nanoparticles of the isostructural compound EuFeO3, co-doped with Nd3+ and Cr3+ with the composition Nd0.33Eu0.67Fe1−xCrxO3, we reported an unusual crystal distortion wherein Eu3+ and Fe3+ cations exchange their normal expected A and B sites and novel magnetic properties15.

In this paper, we report on the synthesis of LaFeO3, La0.7Eu0.3FeO3 and La0.7Eu0.3Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles using a mechanical milling route. We then systematically study the effect of Eu3+-doping and Eu3+/Cr3+ co-doping on the structural and magnetic properties of the synthesized nanoparticles. Of special interest to us is studying the contribution of the majority Eu3+ and minority Eu2+ ions detected on the intrinsic magnetic properties of the nanoparticles. As the investigated compounds have AFM ground states, it is important to carefully synthesize them as single phases so as to eliminate any contribution of Fe or Fe-oxide impurities on these magnetic properties. The experimental techniques used include X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and 57Fe Mӧssbauer spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and vibrating sample (VSM) magnetometery.

Materials and methods

LaFeO3, La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles were prepared starting from stoichiometric mixtures of high-purity α-Fe2O3, La2O3, Eu2O3 and Cr2O3 that were subjected to mechanical milling for different times using a Fritch D-55743 P6 milling machine with tungsten carbide vial (250 mL) and balls. The milling speed was 300 rpm, and the ball-to-powder mass ratio was 15: 1. A Carbollite (HTF 1800) furnace was used to heat the pre-milled mixtures for 10 h at various temperatures to achieve single-phased final products. XRD measurements were performed using an X’Pert PRO PANanalytical diffractometer where the Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) was employed in the 2θ-range of 20.00–80.00° at the rate of 0.02° per second. The GSAS program was used to perform XRD Rietveld refinements20. A JEM-1400-JEOL system, operating at 200 kV, was used to obtain high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images. A PerkinElmer SpectraOne system was used to collect FT-IR spectra in the range 500–4000 cm−1 with a signal resolution of 4 cm−1 for 40 scans. 57Fe Mössbauer measurements were done at 298 K and 78 K with a conventional constant acceleration spectrometer using the 14.4 keV gamma ray provided by a 50 mCi 57Co/Rh source operating in transmission mode. The isomer shift values are quoted relative to α-Fe at 298 K. An Omicron NanoTechnology MXPS system (Scienta Omicron, Germany) employing the Al Kα radiation (hν = 1486.6 eV) was used to collect XPS spectra. The C 1s reference peak, at the binding energy of 284.6 eV, was used for binding energy calibration, and the data was fitted with the CasaXPS21. The VSM magnetometer option of a Quantum Design PPMS system was used to record the thermal dependence of magnetization. The measurements were carried out in both the field cooling (FC) and zero field cooling (ZFC) modes under an external magnetic field of 50 kOe in the 4–300 K temperature range. ZFC magnetic hysteresis loops were obtained at different temperatures and applied fields of up to 9 T.

Results and discussion

Mechano-synthesis and crystal structure

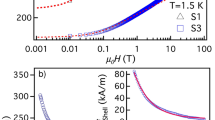

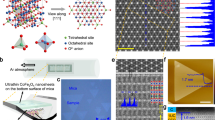

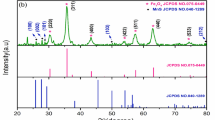

The XRD patterns shown in Fig. 1 indicate that the formation of single-phase LaFeO3 and that of its Eu3+-doped LaFeO3 and Eu3+/Cr3+ co-doped LaFeO3 (La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3) variants are attained after heating the corresponding 80 h pre-milled reactants’ mixtures at 600 °C (10 h) and 700 °C (10 h), respectively. These temperatures are ca. 600–700 °C lower than the ones reported for the formation of LaFeO3 and its cation-doped modifications using the conventional solid-state routes22. It is obvious from the TEM images shown in Fig. 2 that the three materials are composed of semi-spherical nanoparticles that tend to agglomerate. The LaFeO3 sample exhibits the widest particle size distribution with the mean particle size of (40 ± 10) nm relative to both La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 (30 ± 10) nm. The results of the XRD Rietveld refinements, where in the case of the doped samples a common position for the La3+ and Eu3+ ions was assumed and a temperature factor to account for their disorder was included, are also shown in Fig. 1, Tables 1 and 2. It follows that each nanomaterial is structurally indexable to an orthorhombic perovskite-related phase (space group Pbnm)5,7. As the microstrain values for the doped LaFeO3 samples (Table 2) are too small to be considered a factor contributing to the structural distortion associated with apparent broadened peaks relative the ones expected for the corresponding bulk samples, we attribute the broadening to lattice dislocations and surface disorder associated with crystallite size reduction to the nanometer scales23. The relatively large values of the microstrain in the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 samples, relative to that of the LaFeO3 sample, are obviously induced by cationic doping and co-doping. The data given in Tables 1 and 2 were used in combination with VESTA software24 to draw the polyhedra of the crystal structure of LaFeO3 with the ionic positions, bond lengths, and angles shown in Fig. 3.

Observed, calculated and difference of the XRD patterns for the (a) LaFeO3, (b) La0.70Eu0.30FeO3, and (c) La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 samples. The Miller indices of each peak are given in the form of (hkl) and the blue bars indicate the positions of Bragg’s reflection peaks. The inset shows the relative intensity reversal of the (220) and (024) peaks.

The polyhedra of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles as derived from the XRD Rietveld refinement. The large gray spheres represent La3+ ions in 8 O2− coordinated sites, the orange spheres refer to Fe3+ ions in FeO6 octahedra and the small green spheres represent O2− ions. O1 and O2 refer to O2− ions with two different environments.

For the LaFeO3 nanoparticles, the difference between the distances of La3+ to its eighth and ninth nearest O2− neighbors, 2.527 Å and 3.028 Å, is larger than that expected for bulk LaFeO3 mentioned earlier8,10. This, in turn, justifies the conclusion that the La3+ polyhedron at the A-site of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles is LaO8 rather than LaO12 as expected for bulk LaFeO38,10. This result indicates that the change in the La3+ coordination number is strongly instigated by the weakening of ionic exchange interactions at the surface of the nanoparticles. From Table 1, it can be seen that the Fe–O1 bond lengths vary coincidentally with the FeO6-volumes. There was no cationic site exchange similar to that we previously reported for EuFexCr1−xO3 nanocrystalline particles using a similar mechano-synthesis regime25. The fact that the lattice constants of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles are slightly smaller than those of their bulk counterparts cited above22 may be attributed to the dislocations and disorder induced on the surface layers of the nanoparticles. The FeO6 octahedra in the LaFeO3 nanoparticles (Fig. 3) appeared to be severely distorted owing to variations in the intra-octahedral O1–Fe–O2 bond angles.

It is clear from the obtained lattice parameters of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles that their distorted crystal structure is of the O′-type6. The diffraction peaks of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles broadened and shifted toward larger angles (Fig. 1). Hence, their lattice constants decreased relative to those of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles (Table 1). These changes entail the substitution of 8-coordinated La3+ ions (1.36 Å) with smaller 8-coordinated Eu3+ ions (1.066 Å) in the lattice structure of LaFeO326. Generally, the influence of the Eu3+ dopant on the deformation of octahedral sites is justifiable in terms of the Goldsmith formalism7. In contrast to the LaFeO3 nanoparticles, it can be seen from Table 1 that doping with Eu3+ affects the lattice constants of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles, such that a < c/\(\sqrt 2\) < b indicates that the orthorhombic distortion of the nanoparticles is O-type. We associate this crossover of the a and c/\(\sqrt 2\) parameters with the significant difference between the O1-Fe-O2 angle in the Eu3+-doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles and LaFeO3 nanoparticles (Table 1) owing to the partial substitution of La3+ ions with smaller Eu3+ ions. Similar anomalous parameter crossovers have been reported for solid solutions of rare-earth orthoferrites and orthocobaltites, such as PrCo1−xFexO3 and EuCo1−xFexO327,28. To reflect more on the structural distortion resulting from Eu3+ doping, using Glazer's tilt system of perovskites29, one notes that the variation in the lattice parameters of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles corresponds to the first tilt type along the [010] direction. As shown in Table 1, partial substitution of La3+ with Eu3+ led to a single long Fe-O2 bond along the b-axis and a pair of Fe-O1 and Fe-O2 short bonds in the ac plane.

We now turn to La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles. As shown in Table 2, the Eu3+ and La3+ ions preferentially occupy a slightly distorted “average” A-site, whereas the Cr3+ ions are randomly distributed with Fe3+ ions in the B-sub-lattice.. It turns out that the introduction of 5% Cr3+ (0.615 Å) substituent ions for Fe3+ (0.645 Å)26 resulted in a slight increase in the a lattice parameter and a concomitant decrease in the b and c lattice parameters relative to those of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles. The estimated crystallite sizes for the three types of nanoparticles were within experimental error, consistent with the particle sizes deduced from the TEM measurements. This implies that the nanoparticles may generally be considered crystallites.

The FT-IR spectra of the mechano-synthesized LaFeO3 nanoparticles and their Eu3+-doped and Eu3+/Cr3+-co-doped modifications in the range of 400–700 cm−1 shown in Fig. 4 are typical of perovskite oxides that structurally index to the Pbnm space group4,7. Theoretically, Pbnm phases have nine dipole-active optical phonon modes in the 400–700 cm−1 range, of which those between 400 and 500 cm−1 are O2− octahedral bending vibrations, and those beyond 500 cm−1 are O2− stretching vibrations7,30. However, some peaks are very difficult to detect because of the line broadening associated with the small particle sizes or the possible presence of O2− vacancies on the surfaces. Evidently, the slight differences in the FT-IR spectra relative to the spectrum of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles were a consequence of cationic doping. On the basis of the ionic interactions present, the vibrational bands would contribute intrinsic Lorentzian shapes to the FT-IR spectrum. Temperature-dependent effects, instrumental effects, and/or sample characteristics cause the background signals to experience Gaussian broadening31,32. Hence, we opted to fit the FT-IR spectra shown in Fig. 4 with the Voigt functions. The spectral broadband at ~ 588 cm−1, for the LaFeO3 nanoparticles was assigned to the antisymmetric stretching vibrational modes of the FeO6 octahedra7. The relatively asymmetric peak may be related to the non-uniform cationic distribution in the shells of the nanoparticles, which leads to cluster-glass-like features14. Peak broadening reflects the wide size distribution observed in the TEM image (Fig. 2). The weak band at ca. 505 cm−1 owing to the out-of-phase stretching vibrations of the BO6 octahedra, as has been observed for some orthochromites and orthomanganites32, is closely associated with a Jahn–Teller-like distortion30. For Eu3+-and Eu3+/Cr3+-doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles, the notable enhancement in the symmetry of the stretching vibrational modes and their narrowing are indicative of a more uniform cationic distribution and limited particle size range relative to those of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles. The substitution of the lighter La3+ ions (138.904 amu) by heavier Eu3+ ions (151.962 amu) in the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles shifted the absorption band of the FeO6 stretching vibrations from 583 to 574 cm−1, which is expected, as the wavenumber is inversely proportional to the ionic mass18,33. The small concentration of Cr3+ ions in the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles was not sufficient to cause an observable shift for the same band relative to that of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles. The small shoulder at 505 cm−1, associated with the O′-type structural mode of LaFeO3 does not exist in the Eu3+-doped and Eu3+/Cr3+-co-doped nanoparticles, presumably because of the O-type structural distortion. We now turn to The shifts in the bending vibrational mode at 426 cm−1 in the FT-IR spectrum of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles to 432 cm−1 and 431 cm−1 in the spectra of La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3, respectively. These shifts are consistent with the increased bending of the Fe–O2–Fe angle revealed by the XRD refinement of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles and the subsequent decrease in the electronegativity of Cr3+–O2− compared with Fe3+–O2− in the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles. Hence, the FT-IR spectra further confirmed that LaFeO3 nanoparticles and their Eu3+-doped and Eu3+/Cr3+ co-doped modifications were formed.

Mössbauer characterization

The zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer spectra of LaFeO3, La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles, recorded at 298 K and 78 K, are shown in Fig. 5, and the corresponding fitted hyperfine parameters are given in Table 3. All spectra show pure magnetic six-line patterns with broadened absorption lines, which reflect both the particle size distribution and varied cationic environments for the doped samples around the 57Fe nuclei. It is pertinent to note that Fujii et al.1 reported Mössbauer spectra for LaFeO3 nanoparticles with an average particle size of ca. 13 nm, which are pure doublets. While the LaFeO3 system is essentially AFM in character, the Mössbauer doublets were attributed to the superparamagnetic behavior of the FM nanoparticle shells that resulted from the uncompensated surface spins1. The absence of such doublets in the Mössbauer spectra of the present nanoparticles rules out the presence of any superparamagnetic behavior, which is consistent with their relatively larger average particle sizes relative to 13 nm1,14. The Mössbauer spectrum of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles at either 298 or 78 K was best fitted to a single sextet with a typical isomer shift value of the Fe3+ state11,34. The isomer shift values at 298 K (0.37–0.41 mm/s) indicate the high-spin nature of the Fe3+ ions in all nanoparticles6. The increase in the isomer shift values at 78 K relative to their values at 298 K is explicable in terms of the second-order Doppler shift34. The small negative quadrupole shift values at both temperatures are indicative of the distorted crystal structures, as discussed earlier6,11. We associate the relatively high value of the hyperfine magnetic field of the LaFeO3 sample at 298 K (51.5 T), which is typical for nanoparticles exhibiting AFM ordering with strong Fe–Fe coupling, with Fe nuclei at the nanoparticle cores1,6. The tangible increase in the hyperfine field value as the temperature is decreased to 78 K (Table 3) is associated with the removal of the thermal vibrations and subsequent spin alignment, especially in the shells of the nanoparticles1,13,15,34. As shown in Fig. 5 and Table 3, doping the LaFeO3 nanoparticles with Eu3+ and co-doping them with Eu3+/Cr3+ broadened the Mössbauer absorption lines. The best fit of the spectra of both doped nanoparticles was attained using two superimposed magnetic subspectra, S1 and S2. S1, with smaller isomer shifts and larger effective hyperfine magnetic fields, are associated with Fe3+ environments similar to those in undoped LaFeO3 or with poor Eu3+ (in La0.70Eu0.30FeO3) and Eu3+/Cr3+ (in La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3) environments. The slight decrease in the hyperfine field values of sextet S1 at both temperatures for both types of doped nanoparticles relative to those of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles is attributed to their relatively smaller average particle size, as revealed by the TEM images. Slight differences existed between the isomer shift values of the undoped LaFeO3 nanoparticles and those of the S1 sextet. This may be related to the different electronic configurations of the dopant ions that, in turn, lead to slightly different electric fields at the sites of 57Fe nuclei34. Sextet S2, whose hyperfine magnetic fields are notably smaller than those of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles, is associated with Fe3+ environments where the Fe–O–Fe of the magnetic superexchange interaction of pristine LaFeO3 is weakened by the presence of Eu3+ or Eu3+/Cr3+ nearest neighbors in La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 or La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3, respectively. This is supported by the larger linewidth of S2 for the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles, which, in turn, suggests a random distribution in the numbers of Eu3+ and Cr3+ cationic neighbors of the Fe3+ ions at the A and B sites, respectively6,34. The weakening of the S1 and S2 hyperfine magnetic fields in the spectra of the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles implies weakened exchange interactions between Fe3+ ions because of the negative super-transferred hyperfine field produced by the half-filled d-orbitals of the Cr3+ ions at the sites of the 57Fe nuclei35. The fact that the spectral intensities at 298 K and 78 K for both sextets, S1 and S2, are the same supports their assignments to the Fe3+ environments, as described above.

Surface composition: XPS spectral analysis

The La 3d, Eu 3d, Fe 2p and O1s XPS spectra of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles and their Eu3+-doped and Eu3+/Cr3+ co-doped modifications are shown in Fig. 6. The C 1s XPS peak at 284.6 eV was taken as a reference for all charge shift corrections. The La 3d3/2 and La 3d5/2 peaks of the LaFeO3 sample at the binding energies (BE) 850.4 eV and 833.6 eV (Fig. 6a) are similar to those reported for sol–gel processed LaFeO3 nanoparticles7,36. Satellite peaks at BE values 854.4 eV and 837.3 eV correspond to the shake-up of the La 3d3/2 and La 3d5/2 states, respectively, due to electron transfer from the O 2p valence band to empty La 4f states36. As these BE values have been reported for both La2O3 and LaFeO37,37, the existence of some unreacted La2O3 components on the surface of these mechano-synthesized LaFeO3 nanoparticles could not be ruled out. Additionally, these BE values may be partly associated with the very small amounts of Fe-doped La2O338 and/or La-doped α-Fe2O339 intermediate phases that develop during the reaction, leading to the LaFeO3 phase. The BE values of the La 3d3/2 and La 3d5/2 spectra for the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles, 850.8 eV and 834.0 eV, and those of the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles, 849.9 eV and 833.1 eV, are slightly higher than those of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles. This implies that introducing the more electronegative Eu3+ (1.2) for the less electronegative La3+ (1.1) shifts the La 3d spectral peaks towards higher BE values because of the lowering of the electron densities40. Similarly, the lower BE values for the La 3d spectral peaks of the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles relative to those of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles may be attributed to doping with the less electronegative Cr3+(1.66) for the more electronegative Fe3+ (1.83), which increases the La3+ and O2− electron densities and consequently lowers the BE values40.

The (a) Fe 2p, (b) La 3d, (c) Eu 3d, and (d) O 1s core-level XPS spectra recorded from the (i) LaFeO3, (ii) La0.70Eu0.30FeO3, and (iii) La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles. The solid lines represent the best fitting of the experimental data. The estimated error for the binding energy values is ± 0.01 eV.

Figure 6b shows the Fe 2p XPS spectra of all the nanoparticles. The asymmetrical Fe 2p3/2 peak of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles could be decomposed into distinct peaks at BE of 709.5 eV and 711.3 eV corresponding, respectively, to surface Fe2+- and Fe3+-containing species7,41. Previously, we reported a similar reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ on the surface of mechano-synthesized Nd0.33Eu0.67CrxFe1−xO3 nanoparticles15. In addition, the presence of surface Fe2+ ions has been reported for other REFeO3 compounds in the form of bulk or nanoparticles, such as PrFeO342, ErFeO343 and Ir-doped YbFeO344. In fact, the shake-up satellite peak at a BE value of 717.8 eV, which is located at + 8.3 eV from the Fe 2p3/2 peak at 709.5 eV, is typical of satellite signals of ferrous species41. The presence of these Fe2+ impurities suggests the existence of O2− vacancies as balancing defects. Together, these results imply the formation of an O2− defective perovskite phase of LaFeO3-δ at the surface of the nanoparticles45. Hence, we associate the Fe 2p3/2 peak at the BE of 709.5 eV to this surface LaFeO3-δ component. The sub-spectral peak at 711.3 eV is almost similar to that of Fe3+ ions in α-Fe2O3 (711.2 eV). Hence, we associate the 711.3 eV peak with the La-doped α-Fe2O3 intermediate phase implied above by the La 3d XPS spectrum39. The Fe 2p1/2 spectral component was fitted with two peaks centered at the BE values of 723.2 eV and 725.8 eV which are assigned, respectively, to LaFeO3-δ and either or both of LaFeO3 and La-doped α-Fe2O37,36,39. As is seen in Fig. 6b, the binding energies of the Fe 2p3/2 peaks increase for the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles (710.0, 711.7 eV) relative to the corresponding values of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles. This is suggestive that the incorporation of Eu3+ in LaFeO3 results in lesser O2− vacancies hence more Fe3+ ions and, consequently, stronger Fe–O bonds. However, for the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles the binding energies of Fe 2p core-level spectra tend to decrease on the Cr3+ substitution. The reason for this is apparently the same as that we argued above for the similar trend in the La 3d spectra following the Cr3+ substitution.

Each of the Eu 3d core-level XPS spectra of the Eu3+-doped and Eu3+/Cr3+-co-doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles, shown in Fig. 6c, is composed of five peaks. For the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 sample, the peaks were assigned as follows. The Eu3+ doublet at the BE values of 1134.3 eV (Eu 3d5/2) and 1163.6 eV (Eu 3d3/2) is attributed to a surface Eu3+-doped α-Fe2O3, as is reported elsewhere46. The weak Eu2+ doublet at the BE values 1124.4 eV (Eu 3d5/2) and 1154.7 eV (Eu 3d3/2), which is consistent with those reported before for other Eu-containing systems47, merits special attention as it appears to influence the nanoparticles’ low temperature magnetic behavior to be discussed in the next section. The presence of Eu2+ ions, in systems like the present ones, is attributed to an intermediate valence between the electronic configurations of Eu3+ and Eu2+ ions48. This reduction of Eu3+ to Eu2+ is implicative of the presence of balancing O2− vacancies on the surface of nanoparticles. Hence, we associate the Eu2+ doublet with the weak La0.7Eu0.3FeO3-δ surface component. The fifth fitted peak in the Eu 3d core level spectrum, at the BE value 1128.1 eV was not, to our knowledge, reported before for any Eu-containing solid. Hence, we assume that it is due to the investigated La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles. Such an assignment appears logical as the Eu 3d core level XPS spectral peak at the close BE value of 1129.0 eV was assigned before to Nd0.33Eu0.67FeO3 nanoparticles15.

As is clear from Fig. 6c, the presence of Cr3+ in the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles slightly shifts the Eu 3d doublet relative to that of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3, to the BE values of 1133.8 eV and 1163.5 eV. These values are consistent with those reported for EuCrO3 doublets, suggesting the possibility that traces of EuCrO3 are present on the surface of La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles25. In similar lines to those given above, we attribute the Eu 3d core-level XPS peak at the BE value 1123.9 eV and the shake-down satellite at 1154.9 eV, in the spectrum of the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles, to an Eu2+-containing surface component that could be La0.7Eu0.3FeO3-δ and/or La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3-δ47. The fifth peak in the Eu 3d spectrum of the same sample, at the BE value of 1127.6 eV, is negatively shifted and enhanced in intensity relative to the corresponding one in the spectrum of La0.70Eu0.30FeO3. Taken together, these results imply that even a low concentration of the less electronegative Cr3+ relative to the substituted Fe3+ may significantly influence the surface composition of the mechano-synthesized La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles, with the possibility of having surface traces of pure and/or Cr3+-doped La0.70Eu0.30FeO3-δ as well as EuCrO325.

The O 1s XPS spectra of the nanoparticles are shown in Fig. 6d. As we have, previously, done with similarly mechano-synthesized rare earth orthoferrites15, we resolve the O 1s peak for the LaFeO3 nanoparticles into three overlapping peaks. In agreement with the La 3d spectra, the first component of the O 1s peak (I) at a BE value of 528.2 eV is related to perovskite-related LaFeO3 and/or moderately Fe-doped La2O37,36,38. The second component (II) at 529.9 eV is assigned to the α-Fe2O3 and/or La-doped α-Fe2O3, both of which are implicated by the Fe 2p spectra discussed above15,39,41. The LaFeO3-δ phase, whose presence was inferred from the Fe 2p spectra, is associated with the minor third component of O 1s (III) at the BE value of 532.5 eV15,41,45. With Eu3+ doping, the BE of the components of the O 1s peak increased to 529.0 eV (I) and 530.4 (II) eV which, in line with the above analysis, we ascribe to La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and Eu3+-doped α-Fe2O3, respectively46. The positive shift of O 1s, in the XPS La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 spectrum, is possibly due to the decrease in the distance between the O2− ion and their doped Eu3+ neighbors due to the higher electronegativity of Eu3+ relative to that of La3+40. The absence of the third component (III) in the O 1s XPS spectrum of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 sample suggests that doping with Eu3+ results in the elimination of the Fe2+-containing LaFeO3-δ surface component. With the inclusion of the Cr3+ ion, the BE values of the three O 1s XPS peaks decrease slightly to 528.0 eV (I), 529.6 eV (II) and 532.7 eV (III) relative to those of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles. Such a reduction is attributed to the lower electronegativity40 of Cr3+ over Fe3+. Based on previous work, and in line with above analysis, the BE values of these O 1s XPS spectral peaks are assigned, respectively to EuCrO3, Eu3+-doped α-Fe2O3 and pure and/or Cr3+-doped La0.70Eu0.30FeO3-δ surface components25. To summarize, the above XPS data analysis has shown mechano-synthesized Eu3+-doped and Eu3+/Cr3+-co-doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles to have complex surface structures, that contain pure and Eu3+/Cr3+ doped and co-doped LaFeO3 phases, O2-deficient undoped and Eu3+/Cr3+-doped LaFeO3 phases, traces of undoped or doped initial reactants. Such complexity is expected on the surfaces of nanoparticles prepared by mechanical milling and subsequent sintering15,25.

The magnetic properties

Figure 7 shows the temperature dependence of the FC and ZFC magnetization in the range of 2–300 K under an applied field of 50 kOe for LaFeO3, Eu3+-doped, and Eu3+/Cr3+-co-doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles. As expected for a magnetically ordered system, the FC magnetization curves for all samples exhibited similar temperature dependencies to their Mössbauer magnetic hyperfine fields, decreasing with increasing temperature. The wider bifurcation observed for the LaFeO3 nanoparticles reveals stronger thermomagnetic irreversibility in comparison to the Eu3+-doped and Eu3+/Cr3+-co-doped nanoparticles13. The ZFC magnetization of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles initially decreased with decreasing temperature to a minimum and then increased without exhibiting a clear maximum below the bifurcation point49. Based on the Mössbauer data, this could be explained in terms of the core/shell model, as was done by other1,13,16,49 researchers. While the core is AFM in nature, the spins of the glass-like shells assume an FM ordering owing to the AFM spin canting at the cores in addition to the field applied during the measurement. The magnetization enhancement to values similar to those previously reported for LaFeO3 nanoparticles at very low temperatures could result from a local spin order that develops at the interface between the canted AFM cores and FM shells as a result of strong spin coupling9,13,50. With a gradual increase in temperature, the interfacial exchange coupling weakens, while the core spins resist alignment even by a field as high as 50 kOe50. Thus, the core–shell AFM-FM coupling requires higher thermal agitation and/or a higher applied field to be weakened, as manifested by the development of the spin-glass-like behavior at ~ 75 K (Fig. 7). This may explain why spin-glass-like behavior was not detected by zero-field Mössbauer measurements at 78 K. At temperatures higher than 75 K, the spins of the FM shell start to reverse their orientation in the direction of the applied field, and concomitantly, the AFM coupling at the cores starts to decay. Consequently, the ZFC magnetization increased with a further increase in temperature, as observed9,10. Similar behavior was not observed in the FC curve of the same sample because the surface spins were readily aligned in the field direction, resulting in an apparently higher magnetization relative to that obtained in the ZFC case (Fig. 7).

As shown in Fig. 7, with decreasing temperature, the ZFC and FC magnetization values for the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles increased throughout the scanned temperature range. The higher magnetization values for both materials relative to those of the pristine LaFeO3 sample are evidently linked to the introduction of paramagnetic Eu ions as partial substituents for diamagnetic La3+. A comparison of the FC molar susceptibility (χm) values of the three materials, as depicted in Fig. 8, reveals that the magnetic contribution of the Fe3+ ions is barely detectable in LaFeO3 compared to that of the Eu ions in the other two compounds. To determine the contribution of Eu3+ and XPS-detected minority surface Eu2+ ions to the total susceptibility of both the Eu-doped samples, hereafter referred to as χm(Eu), we subtracted χm of the LaFeO3 from that of either. The rationale here is to exclude the magnetic effect of the Fe3+ sublattice, which is similar in all three compounds. Each of the obtained χm(Eu) curves, shown in Fig. 9a (La0.70Eu0.30FeO3) and 9-b (La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3), may be divided into two temperature regions, viz. 2–20 K and 20–300 K. In the first low temperature region, the observed upward ascending trend of χm(Eu) below 20 K is implicative of a Curie–Weiss type paramagnetism that is solely associated with the minority Eu2+ ions having an electronic configuration of [Xe] 4f7 and a theoretical effective magnetic moment μeff of 7.94 μB similar48 to that of Gd3+. In the second region, the behavior of χm(Eu) was attributed mainly to the van Vleck paramagnetism of the Eu3+ excited states48. According to the Russell–Saunders formalism, Eu3+ ([Xe] 4f6) has a total angular momentum (J) of zero and, hence, a nonmagnetic ground state (7F0)53. Nevertheless, Eu3+ has a spin–orbit interaction given by (λL.S) with L and S orbital and spin angular momenta, respectively, and (λ) is the spin–orbit coupling constant47,48,50. In the framework of the van Vleck theory, the fact that the differences between the ground state and the low-lying excited states 7FJ of the Eu3+ ion are of the order of kBT at room temperature (207 cm−1) results in the Eu3+ ions contributing a temperature-dependent term (\(\chi\)) to the paramagnetic susceptibility, whose value depends on λ48. For instance, while for insufficiently large values of λ relative to (207 cm−1), a non-negligible magnetic moment might be observed at low temperatures, the Eu3+ ions contribute a minute van Vleck temperature-independent paramagnetic term (\(\chi_{0}\)) that is linked to the 7F0 state48. Based on the above, the χm(Eu) curves in Fig. 9a,b were not amenable to satisfactory fits by separately applying a Curie–Weiss type equation to the low-temperature data and a van Vleck type equation fit to the data in the ~ 20–300 K temperature range. However, the best fits of each of the χm(Eu) curves in the entire temperature range of 2–300 K were obtained by considering both the temperature-independent and-dependent Eu3+ van Vleck terms in addition to the Eu2+ Curie–Weiss type paramagnetic term using the following equation48:

where n is the relative Eu2+ contribution to the total χm(Eu) in the temperature range of the measurement. By limiting ourselves to the first three excited states of Eu3+, Eq. (1) can be rewritten as follows:

where NA is Avogadro’s constant, θW is the Weiss temperature, a = λ/kBT. The other symbols have the usual meanings. This has yielded for the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles the values of μeff = 0.72μB, θW ~ − 14 K, n = 0.58, λ = 363 cm−1 and \(\chi_{0}\) = 5.3 × 10−5 emu/Oe. mol. Similar values were obtained for the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 except for n and θW, which were found to be = 0.70 and ~ − 11 K, respectively. Starting with the low-temperature upturn in χm(Eu) that we ascribed to Eu2+ spins, it is evident that the negative values of θW imply the presence of AFM interactions among the Eu2+ spins. However, the obtained θW values for both compounds reflect the nature of this weak AFM interaction. The value of μeff = 0.72μB/Eu2+ is very small when compared to the corresponding theoretical value for a free Eu2+ ion (7.94 µB)50. This could possibly reflect the fact that the Eu ions in both materials were in a valence fluctuation state with no localized magnetic moments. We now turn to the remaining part of the scanned temperature range, where the obtained value of λ suggests that the energy interval between the ground state (7F0) and first excited (7F1) state for Eu3+ (4f6) ions, in both compounds, primarily influences the paramagnetic susceptibility above 521 K. This, in turn, explains the weak relative contribution of the Eu3+ van Vleck temperature-dependent susceptibility to the total χm(Eu), viz. 0.42 (La0.70Eu0.30FeO3) and 0.30 (La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3) in the 20–300 K temperature range. The fact that these results are slightly different from those reported for other Eu-containing oxide systems48 could possibly be ascribed to the high applied field (H = 50 kOe), crystal field anisotropy of the distorted crystal structure, and screening effect, as indicated by the increase in the Mössbauer isomer shift of the S2 sextet (Table 3).

Temperature dependence of the FC Eu-related molar susceptibility \( \chi_{m}\) (Eu) for the (a) La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and (b) La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles, obtained by subtracting the molar susceptibility contribution of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles from that of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 ones, respectively, measured in an applied field of 50 kOe. The solid line represents the best fitting line based on Eqs. (1) and (2).

Figure 10 shows that the magnetization values of the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles were lower than those of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles. This is presumably due to the substitution of the weaker magnetic Cr3+ ion (µ = 3 µB) for the stronger Fe3+ ion (µ = 5 µB), which weakens the AFM coupling relative to that of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles13,51. The slight increase in the bifurcation of the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles relative to that of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles can be attributed to an increased interface anisotropy caused by co-doping with both Eu3+ and Cr3+ ions. Considering the limited temperature range used for the FC and ZFC scans, we conclude this section by qualitatively commenting on the irreversibility temperature (Tirr) of the nanoparticles (Fig. 7). The value of Tirr for La0.70Eu0.30FeO3, ~ 287 K, is lower than the corresponding values for the undoped and Eu3+/Cr3+-co-doped LaFeO3 counterparts, both of which could not be determined firmly in the scanned temperature range. The reduction in Tirr for the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 sample relative to that of the LaFeO3 sample can be explained using the argument given above for the enhancement of the ZFC magnetization values to approach those of the FC magnetization owing to doping with Eu3+. Similarly, the higher Tirr of the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles relative to that of the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles is associated with the diminution of the ZFC magnetization values relative to those of the FC, following the introduction of Cr3+ ions.

A final comment in this part goes for the high applied field of 50 kOe used in the FC and ZFC measurements of Fig. 7 and the discussion that followed. This is exactly the same applied field value, deemed necessary to saturate the canted ferromagnetic moments of Fe3+, by Ahmadvand et al.49 in investigating the exchange bias effect in the pristine LaFeO3. This is why it was easy to exclude the contribution of the Fe3+ moments in the above calculations of molar susceptibility. This spin canting arises from the disturbing effect of the crystalline field on the much stronger exchange field, as evidenced by hysteresis loops. Fitting the thermal-dependent magnetization at high field (1.5 kOe ≤ H ≤ 50 kOe) and low temperatures with the Curie–Weiss law, the saturation magnetization almost exclusively represents the rare earth moment, as found in52.

To gain insight into the static features of the magnetic behavior in the three samples, temperature-dependent DC magnetization was performed under an applied field of 100 Oe, as shown in Fig. S1. One notices two distinct glassy states to emerge at ~ 93 K and ~ 90 K for the LaFeO3 nanoparticles, that shift slightly to ~ 92 K and ~ 84 K for both the Eu3+ doped and Eu3+/Cr3+ co-doped variants. This behavior may be linked to the magnetic anisotropy associated with the formation of short-range ordered ferromagnetic clusters and/or a strain-related spin reorientation process for the surface Fe3+ cations53.

The ZFC hysteresis loops of the LaFeO3, La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles were measured at 300 K, 200 K, 100 K and 4 K under an applied field (H) varying between − 9 T and 9 T. Only the loops measured at 300 K and 4 K are shown in Fig. 10. Generally, the loops exhibit a superposition of a dominant contribution ascribed to the AFM core and an FM contribution stemming from both the uncompensated spin-glass shell and canted AFM spins at the core2,11,13,16,19. The values inferred from Fig. 10 for some of the magnetic parameters are listed in Table 42. The fact that a field as high as 9 T is not sufficient to saturate M at all temperatures indicates the dominant AFM behavior of the cores. Moreover, the hysteresis loops of the Eu-containing nanoparticles at 4 K, as compared to the pristine sample, exhibit a linear non-compensated paramagnetic contribution as well as a weak ferromagnetic behavior, as shown in the inset of Fig. 10b. The paramagnetic behavior is obviously due to the Curie Weiss-like behavior that was attributed to the surface Eu2+ ions at low temperatures in the preceding section. The small remnant magnetization (FM contribution) is due to the canted tendency of the FeO6 octahedra, which affects the superexchange of neighboring Fe t2g electrons through Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) interactions19,50. The values of the instantaneous magnetization in the different M-H isotherms follow similar trends to those obtained for the FC magnetization of the nanoparticles (Fig. 8), such that La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 has the highest M values and LaFeO3 has the lowest magnetoelectric coupling in these multiferroic nanoparticles, which reduces the effective magnetic anisotropy54.

While the values of Mmax for the doped nanoparticles decreased with increasing temperature, as expected (Fig. 11a), for the LaFeO3 nanoparticles, Mmax was almost constant in all hysteresis isotherms. This is explicable in terms of the weakening of the exchange coupling of the spins at the AFM/FM core/shell interface, as suggested above, to enhance the ZFC magnetization of the same nanoparticles with temperature. Consequently, under the same maximum applied field (9 T), Mmax was expected to be constant. The values derived from Fig. 10 for the coercivity Hc (= (Hc1 − Hc2)/2), where Hc1 and Hc2 are the coercive fields to the right and left of H = 0 values, are given in Table 4. Clearly, the doped samples had smaller Hc values relative to the LaFeO3 nanoparticles. This may be partly explained in terms of the Stoner-Wohlfarth model, which relates the reduction in Hc to a corresponding reduction in magnetocrystalline anisotropy55. The smaller average particle sizes of the doped nanoparticles relative to those of the LaFeO3 ones enhance the influence of the uncompensated surface spins that become susceptible to easy flipping by the applied field, thereby reducing Hc. It is interesting to note from the temperature dependence of Hc in Fig. 11b that, rather than becoming magnetically harder with decreasing temperature, the mechano-synthesized LaFeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles softened as the temperature decreased from 200 to 4 K. For the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles, this range extends to 300–4 K. Such an unusual thermal dependence of Hc has been reported before for sol–gel prepared LaFeO3 nanoparticles, where the coercivity was found to decrease by ca. 15% upon cooling from 220 to 5 K49. In the present case, Hc for the LaFeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 has been significantly reduced by ca. 70% and 90%, respectively, between 200 and 4 K. For the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3, it has dropped by ~ 95% as the temperature was changed from 300 to 4 K. This anomalous magnetic softening may be attributed to the competition between the magnetic anisotropy and magnetoelectric coupling in these multiferroic nanoparticles, which reduces the effective magnetic anisotropy56.

The negative Hc shifts in the M-H loops for all the samples (Fig. 10) imply the presence of an exchange bias (EB) anisotropy. This is further evidence that the nanoparticles are composed of AFM cores and FM-like shells because EB is known to develop owing to the competition between the exchange and Zeeman energies at the interface of both magnetic structures49. The values of the EB fields, EB (= (Hc1 + Hc2)/2), for the different nanoparticles are listed in Table 4, and their thermal variation is depicted in Fig. 11c. It can be observed that the EB fields increased, reaching a maximum value at 100 K, and then decreased with increasing temperature. The temperature dependence of the EB fields can be related to the thermal activation of the spin reversal in the AFM cores of the particles, which plays a significant role in inducing EB anisotropy in the FM/AFM interfaces of the nanoparticles13,52. Initially, the applied field induced a preferred spin alignment in some nanoparticles. When the field direction is reversed, the spins in some nanoparticles, particularly those with large volumes, may not gain sufficient thermal energy to reverse direction. Consequently, the core spins of these nanoparticles did not contribute to the hysteresis loop during the entire cycle, thereby inducing spontaneous EB anisotropy13. This may explain why the LaFeO3 nanoparticles, which had the largest particle size and size distribution, as shown in Fig. 2, had the highest EB fields relative to the doped nanoparticles. Throughout the temperature range investigated, the lowest EB values were recorded for La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 nanoparticles. As the EB field values in Fig. 11c reflect the strength of the exchange magnetic coupling, it is evident that doping with Eu3+ ions weakens the coupling in the AFM cores. The sharp suppression of EB in the doped nanoparticles at 4 K may demonstrate the robust low-temperature impact of the relatively small amount of surface Eu2+ ions, as indicated by the susceptibility analysis above. The slight increase in the EB field values for the La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles relative to those of La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 may be attributed to the distribution of the dopant Cr3+ ions in the La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 ionic matrix, where the formation of the Cr3+–O2−–Cr3+ AFM superexchange interaction is more favorable13 than that of Fe3+–O2−–Cr3+. This in turn strengthens the overall exchange coupling within the AFM cores. As a final comment in this section, we note that the present mechano-synthesized LaFeO3 nanoparticles show higher EB fields than those of similar sizes prepared using other synthesis routes. For example, at 300 K, the EB value was ~ 217 Oe relative to 139 Oe for LaFeO3 nanoparticles prepared via the sol–gel route57 and ~ 8.523 kOe (4 K) relative to 1.205 kOe (5 K)49. Apparently, this is related to the complex surface composition induced by the mechano-synthesis route, as discussed in section “Surface composition: XPS spectral analysis”, which has no counterpart in the case of LaFeO3 nanoparticles prepared using other techniques.

Conclusion

Single-phase perovskite-related LaFeO3, La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and La0.70Eu0.3Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles (20–50 nm) were mechano-synthesized at 600 °C (10 h) for the pure and 700 °C (10 h) for the two variants. These temperatures are substantially lower by ~ 600–700 °C than those at which the corresponding bulk materials are traditionally synthesized using solid-state methods. Upon Eu3+ doping and Eu3+/Cr3+ co-doping, the perovskite-related orthorhombic LaFeO3 structure undergoes a transition from the usual O′-type distorted orthorhombic structure of orthoferrites to the O-type structure. Eu3+ ions preferentially occupy the A-sites in the crystal structure of LaFeO3, whereas Cr3+ ions are randomly distributed over the octahedral B-sites, and the bond angles and lengths are sensitive to doping and co-doping. Both 57Fe Mӧssbauer and magnetic measurements suggested that the nanoparticles were composed of dominant canted AFM cores and FM shells because of uncompensated surface spins, and no superparamagnetism was observed. The increase in ZFC magnetization of the LaFeO3 nanoparticles at relatively low temperatures is attributed to the resistance of the core spins; hence, the local spin order that develops at the interface between the canted AFM cores and FM shells is to be aligned by the applied magnetic field. The magnetization of the nanoparticles was sensitive to the presence of Eu3+ and Cr3+ ions. The La0.70Eu0.30FeO3 and La0.70Eu0.30Fe0.95Cr0.05O3 nanoparticles were found to display Eu3+ van-Vleck-type paramagnetic molar susceptibility with a spin–orbit coupling constant of 363 cm−1 in the ~ 20–300 K range and a Curie–Weiss like behavior below 20 K due to the minority of the surface Eu2+ ions. The θW and μeff values obtained at low temperatures for the Eu-doped nanoparticles suggest a weak AFM interaction between the Eu2+ ions and the Eu2+/Eu3+ valence state fluctuations, hence the absence of localized Eu magnetic moments. All nanoparticles exhibited anomalous magnetic softening with decreasing temperature, which is referred to as the competition between magnetic anisotropy and magnetoelectric coupling. The nanoparticles reveal temperature-dependent dopant-sensitive exchange bias fields that manifest their AFM/FM core–shell nature, reflecting the thermal activation of the spin reversal at their cores.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

12 September 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72330-1

References

Fujii, T., Matsusue, I. & Takada, J. Superparamagnetic behaviour and induced ferrimagnetism of LaFeO3 nanoparticles prepared by a hot-soap technique. Adv. Aspects Spectrosc. 373, 373–390 (2012).

Köferstein, R., Jäger, L. & Ebbinghaus, S. G. Magnetic and optical investigations on LaFeO3 powders with different particle sizes and corresponding ceramics. Solid State Ion. 249–250, 1–5 (2013).

Mukhopadhyay, K., Mahapatra, A. S. & Chakrabarti, P. K. Multiferroic behavior, enhanced magnetization and exchange bias effect of Zn substituted nanocrystalline LaFeO3 (La(1–x)ZnxFeO3, x = 0.10, and 0.30). J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 329, 133–141 (2013).

Sasikala, C. et al. Transition metal titanium (Ti) doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles for enhanced optical structural and magnetic properties. J. Alloys Compd. 712, 870–877 (2017).

Treves, D. Studies on orthoferrites at the Weizmann Institute of Science. J. Appl. Phys. 36, 1033–1039 (1965).

Al-Mamari, R. T. et al. Structural, Mössbauer, and optical studies of mechano-synthesized Ru3+-doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles. Hyperfine Interact. 243, 1–12 (2021).

Triyono, D., Hanifah, U. & Laysandra, H. Structural and optical properties of Mg-substituted LaFeO3 nanoparticles prepared by a sol-gel method. Results Phys. 16, 1–8 (2020).

Marezio, M., Remeika, J. P. & Dernier, P. D. IUCr, the crystal chemistry of the rare earth orthoferrites. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 26, 2008–2022 (1970).

Lakshmana Rao, T. et al. Substitution induced magnetic phase transitions and related electrical conduction mechanisms in LaFeO3 nanoparticle. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 1–8 (2019).

Lakshmana Rao, T., Pradhan, M. K., Singh, S. & Dash, S. Influence of Zn(II) on the structure, magnetic and dielectric dynamics of nano-LaFeO3. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 31, 4542–4553 (2020).

Shikha, P., Kang, T. S. & Randhawa, B. S. Effect of different synthetic routes on the structural, morphological and magnetic properties of Ce doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 625, 336–345 (2015).

Hosseini, S. A. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and catalytic activity of nanocrystalline La1−xEuxFeO3 during the combustion of toluene. Chin. J. Catal. 32, 1465–1468 (2011).

Blessington Selvadurai, A. P. et al. Influence of Cr substitution on structural, magnetic and electrical conductivity spectra of LaFeO3. J. Alloys Compd. 646, 924–931 (2015).

Bhame, S. D., Joly, V. L. J. & Joy, P. A. Effect of disorder on the magnetic properties of LaMn0.5Fe0.5O3. Phys. Rev. 72, 1–7 (2005).

Al-Rashdi, K. S. et al. Structural, 57Fe Mössbauer and XPS studies of mechano-synthesized nanocrystalline Nd0.33Eu0.67Fe1−xCrxO3 particles. Mater. Res. Bull. 132, 1–12 (2020).

Da Silva, K. L. et al. Mechano-synthesized BiFeO3 nanoparticles with highly reactive surface and enhanced magnetization. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 7209–7217 (2011).

Mahmood, A., Warsi, M. F., Ashiq, M. N. & Ishaq, M. Substitution of La and Fe with Dy and Mn in multiferroic La1−xDyxFe1−yMnyO3 nanocrystallites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 327, 64–70 (2013).

Mitra, A. et al. Simultaneous enhancement of magnetic and ferroelectric properties of LaFeO3 by co-doping with Dy3+ and Ti4+. J. Alloys Compd. 726, 1195–1204 (2017).

Natali Sora, I. et al. Crystal structures and magnetic properties of strontium and copper doped lanthanum ferrites. J. Solid State Chem. 191, 33–39 (2012).

Larson, A. C. & Dreele, R. B. General structure analysis system “GSAS”. Los Alamos National Laboratory Report No., LAUR 86–748 (2000).

Fairley, N. et al. Systematic and collaborative approach to problem solving using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 5, 1–9 (2021).

Acharya, S., Mondal, J., Ghosh, S., Roy, S. K. & Chakrabarti, P. K. Multiferroic behavior of lanthanum orthoferrite (LaFeO3). Mater. Lett. 64, 415–418 (2010).

Popa, N. C. & Balzar, D. An analytical approximation for a size-broadened profile given by the lognormal and gamma distributions. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 35, 338–346 (2002).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Widatallah, H. M. et al. Formation, cationic site exchange and surface structure of mechano-synthesized EuCrO3 nanocrystalline particles. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 44, 1–9 (2011).

WebElements. https://www.webelements.com

Knížek, K. et al. Structural anomalies associated with the electronic and spin transitions in LnCoO3. Eur. Phys. J. B 47, 213–220 (2005).

Pekinchak, O., Vasylechko, L., Berezovets, V. & Prots, Y. Structural Behaviour of EuCoO3 and mixed cobaltites-ferrites EuCo1−xFexO3. Solid State Phenom. 230, 31–38 (2015).

Glazer, A. M. IUCr, the classification of tilted octahedra in perovskites. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 28, 3384–3392 (1972).

Smirnova, I. S. et al. IR-active optical phonons in Pnma-1, Pnma-2 and R3c phases of LaMnO3+δ. Phys. B 403, 3896–3902 (2008).

Stuart, B. H. Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications (Wiley, 2004).

Rao, G. V. S., Rao, C. N. R. & Ferraro, J. R. Infrared and electronic spectra of rare earth perovskites: Ortho-chromites, -manganites and -ferrites. Appl. Spectrosc. 24, 436–445 (1970).

Pence, H. E. & Williams, A. ChemSpider: An online chemical information resource. J. Chem. Educ. 87, 1123–1124 (2010).

Greenwood, N. N. & Gibb, T. C. Mössbauer Spectroscopy (Chapman and Hall Ltd, 1971).

Kuznetsov, M. V., Pankhurst, Q. A., Parkin, I. P. & Morozov, Y. G. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesisof chromium substituted lanthanum orthoferrites LaFe1 − xCrxO3 (0 ≤ x ≤ 1). J. Mater. Chem. 11, 854–858 (2001).

Cao, E. et al. Enhanced ethanol sensing performance of Au and Cl comodified LaFeO3 nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 1541–1551 (2019).

Moulder, J. F., Stickle, W. F., Sobol, P. E. & Bomben, K. D. In Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (ed. Chastain, J.) (Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Physical Electronics Division, 1992).

Lee, Y. et al. Hydrogen barrier performance of sputtered La2O3 films for InGaZnO thin-film transistor. J. Mater. Sci. 54, 11145–11156 (2019).

Qin, L. et al. Improved cyclic redox reactivity of lanthanum modified iron-based oxygen carriers in carbon monoxide chemical looping combustion. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 20153–20160 (2017).

Schaffer, J. P., Saxena, A., Antolovich, S. D., Sanders, T. H. J. & Warner, S. B. The Science and Design of Engineering Materials 2nd edn. (WCB/McGraw-Hill, WCB, 1999).

Mills, P. & Sullivan, J. L. A study of the core level electrons in iron and its three oxides by means of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 16, 723–732 (1983).

Huang, S. et al. High-temperature colossal dielectric response in RFeO3 (R = La, Pr and Sm) ceramics. Ceram. Int. 41, 691–698 (2015).

Ye, J. L., Wang, C. C., Ni, W. & Sun, X. H. Dielectric properties of ErFeO3 ceramics over a broad temperature range. J. Alloys Compd. 617, 850–854 (2014).

Polat, O. et al. Electrical characterization of Ir doped rare-earth orthoferrite YbFeO3. J. Alloys Compd. 787, 1212–1224 (2019).

Cao, E. et al. Enhanced ethanol sensing performance for chlorine doped nanocrystalline LaFeO3-δ powders by citric sol-gel method. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 251, 885–893 (2017).

Freyria, F. S. et al. Eu-doped α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles with modified magnetic properties. J. Solid State Chem. 201, 302–311 (2013).

Cho, E.-J. & Oh, S.-J. Surface valence transition in trivalent Eu insulating compounds observed by photoelectron spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 59, 15613–15616 (1999).

Ranaut, D. & Mukherjee, K. Van Vleck paramagnetism and enhancement of effective moment with magnetic field in rare earth orthovanadate EuVO4. Phys. Lett. A 465, 128710 (2023).

Ahmadvand, H. et al. Exchange bias in LaFeO3 nanoparticles. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 43, 1–5 (2010).

El-Moez, A., Mohamed, A., Álvarez-Alonso, P. & Hernando, B. The intrinsic exchange bias effect in the LaMnO3 and LaFeO3 compounds. J. Alloys Compd. 850, 1–8 (2021).

Widatallah, H. M. et al. Structural, magnetic and 151Eu Mössbauer studies of mechano-synthesized nanocrystalline EuCr1−xFexO3 particles. Acta Mater. 61, 4461–4473 (2013).

Paul, P., Ghosh, P. S., Rajarajan, A. K., Babu, P. D. & Rao, T. V. C. Ground state spin structure of GdFeO3: A computational and experimental study. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 518, 167407 (2020).

Warshi, M. K. et al. Cluster glass behavior in orthorhombic SmFeO3 perovskite: Interplay between spin ordering and lattice dynamics. Chem. Mater. 32, 1250–1260 (2020).

Dash, B. B. & Ravi, S. Structural, magnetic and electrical properties of Fe substituted GdCrO3. Solid State Sci. 83, 192–200 (2018).

Nogués, J. & Schuller, I. K. Exchange bias. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 192, 203–232 (1999).

Ahmmad, B., Islam, M. Z., Billah, A. & Basith, M. A. Anomalous coercivity enhancement with temperature and tunable exchange bias in Gd and Ti co-doped BiFeO3 multiferroics. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 49, 09 (2016).

Stoner, E. C. & Wohlfarth, E. P. A mechanism of magnetic hysteresis in heterogeneous alloys. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 240, 599–642 (1948).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) for providing the PhD scholarship for RTA. We also thank the staff of CAARU, College of Science, SQU, for helping with various measurements. HMW thanks Intisar Sirour for supporting this research in several ways. We are thankful to Drs. Ayman Samara and Abdelmajid Salhi of Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Qatar and Prof. Mohamed Henini of the University Nottingham, UK for assistance with magnetic measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.T.A. did the experimental investigation, analysis, conceptualization and wrote the initial draft. H.M.W. proposed and supervised the project, contributed to the analysis and the conceptualization, wrote the final draft. M.E.E. co-supervised the project and reviewed the manuscript. A.M.G contributed to the Mossbauer measurements and analysis. A.D.A co-supervised the project and reviewed the manuscript. S.H.A. provided laboratory resources and contributed to the XPS analysis and reviewed the manuscript. M.T.Z.M did XPS measurements. N.A. reviewed the final manuscript and MA provided laboratory resources and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the abstract, where the first sentence was incorrect. Additionally, the Acknowledgements section in the original version of this Article was incomplete. Modifications have been made to the Abstract and the Acknowledgements. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Mamari, R.T., Widatallah, H.M., Elzain, M.E. et al. Core and surface structure and magnetic properties of mechano-synthesized LaFeO3 nanoparticles and their Eu3+-doped and Eu3+/Cr3+-co-doped variants. Sci Rep 14, 14770 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65757-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65757-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Nickel-doped LaFeO3 nano particles with n-type polaronic hopping conduction through intra-grain boundary and grain effect

Applied Physics A (2025)

-

Optimization of Eu-doped lanthanum tungstate nanophosphors via surface modification for superior red luminescence and photonic applications

International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials (2025)