Abstract

Electrical conductivity (EC) is widely recognized as one of the most essential water quality metrics for predicting salinity and mineralization. In the current research, the EC of two Australian rivers (Albert River and Barratta Creek) was forecasted for up to 10 days using a novel deep learning algorithm (Convolutional Neural Network combined with Long Short-Term Memory Model, CNN-LSTM). The Boruta-XGBoost feature selection method was used to determine the significant inputs (time series lagged data) to the model. To compare the performance of Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM models, three machine learning approaches—multi-layer perceptron neural network (MLP), K-nearest neighbour (KNN), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) were used. Different statistical metrics, such as correlation coefficient (R), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute percentage error, were used to assess the models' performance. From 10 years of data in both rivers, 7 years (2012–2018) were used as a training set, and 3 years (2019–2021) were used for testing the models. Application of the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model in forecasting one day ahead of EC showed that in both stations, Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM can forecast the EC parameter better than other machine learning models for the test dataset (R = 0.9429, RMSE = 45.6896, MAPE = 5.9749 for Albert River, and R = 0.9215, RMSE = 43.8315, MAPE = 7.6029 for Barratta Creek). Considering the better performance of the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model in both rivers, this model was used to forecast 3–10 days ahead of EC. The results showed that the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model is very capable of forecasting the EC for the next 10 days. The results showed that by increasing the forecasting horizon from 3 to 10 days, the performance of the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model slightly decreased. The results of this study show that the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model can be used as a good soft computing method for accurately predicting how the EC will change in rivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rivers, as a notable source of freshwater, represent a valuable natural resource. However, the water quality and quantity have deteriorated owing to the dynamic nature of river bodies and human activities1,2. The electrical conductivity (EC), which is a measure of water’s capacity to conduct electrical current, is a key indicator for assessing and identifying compositional changes3. A high concentration of dissolved solids typically translates to high EC values4. Hence, the EC can be used to identify high salinity levels in irrigation and drinking water when classifying the surface water quality (WQ). The WQ is typically classified based on the sodium content and EC5. For seawater and freshwater, the EC is up to 50,000 μS/cm and 0–1500 μS/cm, respectively. The Wilcox EC-based categorization for irrigation water classifies water with EC levels of 0–750 μS/cm as fine, 750–2000 μS/cm as allowable, and > 2000 μS/cm as unacceptable. EC levels higher than 10,000 S/cm are not acceptable for either human consumption or agricultural usage. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 1993), the recommended maximum EC for drinking water is 1400 \(\upmu\)S/cm. The WQ classification scheme presented by6 is frequently used. In general, the WQ parameters are highly nonlinear, complex, and nonstationary owing to various interconnections with point and nonpoint contamination sources7,8 (Fig. 1A). Therefore, the WQ must be accurately predicted, detected, and quantified to ensure the sustainable use and effective management of water resources9. In fact, ensuring access to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene (Fig. 1B,10 is one of the 17 sustainable development goals for 203011. Given the significance of this goal, environmental engineers must formulate scientific and practical strategies to accomplish the relevant tasks.

Although several approaches have been proposed to quantify WQ over the past three decades12,13, it remains challenging to develop a reliable expert prediction system and quantify the WQ using mathematical models14,15. The conventional methods for WQ modeling, such as multilinear regression, are linear models that only partially capture nonstationarities and nonlinearities in the environmental dataset because they presume the stationarity of data9,16. Furthermore, the classical machine learning (ML) models typically require considerable data, frequent parameter adjustments, and significant reaction time17,18. Therefore, such methods are not suitable for WQ prediction or quantification. To address these problems, several ML models for modeling surface WQ parameters have been developed, which do not necessitate complicated algorithms and theory19,20,21, such as kernel models, fuzzy set logic, neural network models, ensemble models, hybrid ML models, decision tree models, and integrative ML data pre-processing models.

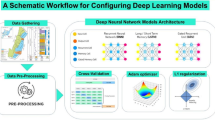

ML model development involves several steps, such as data pre-processing, internal parameter tuning, and input feature optimization, and several advancements have been made in the relevant domains9,22,23,24. Notably, the focus of this study is deep learning (DL) models, as a recently developed subset of ML models25,26, and their integration with feature input optimization algorithms27 to establish a hybrid ML model for river EC prediction. In general, hybrid models can be implemented at either the optimization or prediction stages, depending on their intended use. Hybrid models integrate different optimization strategies and methodologies, thereby resulting in superior modeling accuracies than those achieved using single models. Researchers have highlighted that the key challenge in WQ prediction is the dominant linear-correlation-pattern-based feature extraction. Nonlinear input features affect the prediction capability for nonlinear and nonstationary problems. Considering these aspects, the primary objective of this study is to evaluate the possibility of Boruta feature selection using the XGB technique for identifying the most sensitive related attributes of the target (i.e., EC) variables. A valuable tool for assessing variations in time series, feature selection frameworks can be integrated as a preliminary step in prediction based on ML models to clarify the key features for learning the prediction matrix and provide useful information regarding the physical form of the predictand–predictor relationship.

Previous water quality modeling efforts using conventional statistical and machine learning methods have shown limitations in fully capturing parameters' nonlinear and nonstationary behavior over time. These approaches also require large datasets and frequent tuning, making them unsuitable for real-time predictive needs. There is a need to develop data-driven techniques that can reliably forecast water quality variables several days into the future to support informed decision-making across various sectors reliant on river resources. Accurate multi-step predictions are crucial for optimal water resource planning and management. This study aims to address existing gaps by developing a hybrid machine learning framework integrating Boruta-XGBoost feature selection with a Convolutional Neural Network-Long Short-Term Memory (CNN-LSTM) model. This ensemble methodology leverages the strengths of optimization algorithms and deep sequence learning architectures for water quality modeling.

The objectives of this study can be summarized as follows: (1) Forecast the EC using four ML approaches: convolutional neural network combined with long short-term memory model CNN-LSTM, multi-layer perceptron neural network (MLP), K-nearest neighbor (KNN), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). (2) Optimize the input data using a novel feature selection technique (Boruta combined with XGBoost algorithm). (3) Compare the performances of different models using various statistical metrics and graphical approaches such as scatter plots and Taylor diagrams. (4) Forecast multi-step ahead EC using the model with the best statistical metrics.

Material and methods

Study area

Albert River

The Albert River is a perennial river located in Queensland in southeast Australia. With a catchment area of 782 square kilometers, this river is located within the Gold Coast and Scenic Rim Region local government regions. The EC data of Albert River were collected from Bromfleet station (145102B), located at − 27.91 °S and 153.11 °E (http://www.bom.gov.au/waterdata/).

Barratta Creek

Barratta Creek is located in North Queensland, Australia. The source is located beneath Bunkers Hill in the Leichhardt Range of the Great Dividing Range, and the creek runs north-eastward. The stream continues through largely uninhabited land beyond Woodhouse Mountain, flows virtually parallel to the Haughton River, crosses the Bruce Highway, enters Bowling Green Bay Conservation Park, and empties into Bowling Green Bay at Jerona before joining the Coral Sea. Along its 109-km length, the river drops 224 m. The EC data of Barratta Creek were collected from Barratta Creek at Northcote (119101A) located at − 19.69 °S and 147.17 °E (http://www.bom.gov.au/waterdata/).

Figure 2 shows the locations of stations at which the EC data were collected.

Locations of stations at which the EC was measured (The map was generated using ArcGIS software, version 10.8: https://support.esri.com/zh-cn/products/desktop/arcgis-desktop/arcmap/10-8-1), Australia shape file is from (https://www.abs.gov.au) and maps of River stations are from (http://www.bom.gov.au/waterdata/).

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the EC data for both stations. The average observed EC values were 459 and 380 for Albert River and Barratta Creek, respectively. According to the coefficient of variation (C.V) values, the variation in the EC in Albert River (C.V = 34.8%) was larger than that in Barratta Creek (C.V = 31.1%). Figure 3 shows the time series and frequency distribution of the EC values in both stations.

Boruta-XGBoost feature selection

The Boruta technique is a random forest algorithm wrapper named after the forest god from Slavic mythology28 that computes the Z-scores of each predictor's input for the shadow attribute. The major predictor variables are established by the distribution of Z-score metrics29. In this study, instead of a random forest, the XGBoost ensemble algorithm was used to calculate the Z-score30. The process flow of the Boruta algorithm can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Random shadow characteristics are created. All data characteristics are shuffled at random, and their numerical order is altered.

-

2.

The XGBoost technique calculates the relevance, expressed by the Z-score, of both the shadow characteristics and original features.

-

3.

The essential characteristics are selected. An original feature with a Z-score greater than the largest Z-score in the set of shadow features is designated as “important”. An original feature with a Z-score considerably lower than that of the shadow features is tagged as “not important” and deleted permanently from the feature set.

-

4.

Steps 1–3 are continued until the significance of all qualities has been marked or the set number of iterations is reached.

-

5.

Details can be found in the work of31.

MLP

MLP, as an architecture of artificial neural networks (ANNs) has been widely employed in various disciplines32,33,34,35. Similar to other ANN architectures, the MLP receives input signals and processes them before they are transmitted to the other neurons in the hidden layer(s). At least one hidden layer exists in the MLP structure. During the training phase, the neurons in each layer are linked to the neurons in the adjacent layer through a weight. Sigmoid and linear activation functions are typically used in the hidden and output layers to examine the input data characteristics36. The MLP can be expressed mathematically as follows:

where \(q\) is the number of hidden neurons, \(x_{p} \left( k \right)\) is the input signal, \(S_{q} \left( k \right)\) is the output of the \(q\)th hidden neuron, and \(f\) is the tangent hyperbolic function. The activation function of the output neuron is linear (purelin). Two sets of weights must be updated: those of the input to hidden layer(s), denoted by vector \(W^{I} \left( k \right)\)), and those of the hidden to output layers, denoted by vector \(W^{O} \left( k \right)\). This study adopts MLP networks using a backpropagation algorithm, which can be considered the most prevalent and popular networks. Backpropagation is a supervised learning method that has been used in several prediction tasks37,38. In this study, the Levenberg–Marquardt technique, as a backpropagation algorithm, was used to train the MLP network.

XGBoost

XGBoost is an improved variant of the gradient boosting tree39. Based on the classification and regression tree theory, XGBoost is a successful solution for regression and classification tasks40,41,42,43. The XGBoost method approximates an objective function (showing the goodness-of-fit) using the quadratic Taylor expansion, enabling more rapid calculations44. The core of the algorithm is to optimize the value of the objective function, which typically has two components (training loss and regularization):

where L is the loss function of training, and \({\Omega }\) is the regularization term. The training loss is used to evaluate the performance of the model on training data. The regularization term seeks to limit the model complexity, such as overfitting45. The complexity can be defined in several ways, with the following expression commonly used for each tree:

where T is the number of leaves, and \(\omega\) represents the vector of leaf scores. The structural score is the following objective function:

where \(\omega_{j}\) are distinct values. The quadratic form \(G_{j} \omega_{j} + \frac{1}{2}\left( {H_{j} + \lambda } \right)\omega_{j}^{2}\) is the optimal \(\omega_{j}\) for a given structure \(q\left( x \right)\). Figure 4 illustrates the structure of the XGBoost model.

KNN

KNN, developed by46, is a well-known ML method for addressing regression and classification problems. The technique includes a variable parameter, k, which represents the number of nearest neighbors. The KNN algorithm operates by locating the data point(s) or neighbors from a training dataset that are the closest to a query point. After selecting the k closest data points, a majority voting rule is applied to determine which class is the most prevalent. The most frequent category is determined to be the final classification for the query. The KNN for regression involves four steps:

-

1.

Determine the distance between the query sample and labeled samples.

$$d\left( {x_{tr} ,x_{t} } \right) = \sqrt {\mathop \sum \limits_{n = 1}^{N} w_{n} \left( {x_{tr,n} - x_{t,n} } \right)^{2} }$$(5)

where \(N\) is the number of input features; \(x_{tr,n}\) and \(x_{t,n}\) are the nth feature values of the training (\(x_{tr}\)) and testing (\(x_{t}\)) points, respectively; and \(w_{n}\) is the weight of the \(n\)th feature that ranges between 0 and 1.

-

2.

Arrange the labeled instances in ascending order of the distance.

-

3.

Define the ideal number of neighbors based on the root mean squared error (RMSE), e.g., through cross-validation.

-

4.

Calculate the average distance inversely using the k-nearest neighbors.

CNN-LSTM

In this study, modern DL techniques are used to develop a prediction model for forecasting the EC in rivers. The CNN-LSTM framework contains two key components: (1) convolutional and pooling layers that perform complicated mathematical operations to produce input data features, (2) LSTM and dense layers that process the obtained features47.

CNN layer

The one-dimensional CNN (1D-CNN) is a deep feedforward neural network with local connections and weight sharing properties48. CNNs can automatically extract high-level dependence characteristics from input data. The learning performance and training duration of the model are determined by its structure, particularly the number of layers. A shallow structure may have inadequate performance, whereas an excessively deep CNN may deteriorate the temporal sequential element of the data or be vulnerable to overfitting49.

Typically, the CNN network architecture has convolutional and max-pooling layers50. The CNN filter slides along the time axis, and its input is a three-dimensional tensor. The number of CNN convolution kernels is typically determined by the complexity of the objective. A batch normalization layer is added after the convolution layer to enhance the model performance51. Overall, CNNs consist of several layers such as the input layer, convolutional layers, nonlinear activation layer, pooling layers, dropout layer, batch normalization layer, one or more completely connected layers, and loss activation layer. Figure 5 shows the structure of the CNN model.

LSTM layer

The LSTM is a version of the recurrent neural network: memory blocks composed of memory cells connected by layers, unlike the neurons in ANNs. The approach was proposed by52 and improved by53 to address the gradient disappearance problem. Each LSTM unit consists of a memory cell and three primary gates: input, output, and forget gates54. By determining the information to be forgotten and remembered, the LSTM generates a regulated information flow and learns long-term dependencies. Specifically, the input gate \(i_{t}\) and a second gate \(c_{t}^{*}\) control the new information stored in the memory state \(c_{t}\) at time \(t.\) The forget gate \(f_{t}\) regulates the previous information that must be erased or retained on the memory cell at time \(t\)\(-1\), whereas the output gate \({o}_{t}\) determines which information may be used to generate the output of the memory cell. Equations (6–10) represent the processes performed by an LSTM unit55:

\(x_{t }\) represents the input, \(W_{*}\) and \(U_{{* }}\) are weight matrices, \(b_{*}\) represent the bias term vectors, \(\sigma\) is the sigmoid function, and \(\odot\) represents component-wise multiplication. The output of the memory cell, which is the hidden state ht, is computed as

Figure 6 shows the structure of the LSTM cell and CNN-LSTM model that is used to forecast the EC values in rivers.

Model development

A novel hybrid expert system composed of Boruta-XGBoost as the feature extractor and the CNN-LSTM model was developed to forecast the EC in rivers. Boruta-XGBoost, which is a tree-based feature selection method was used because classical statistical methods such as cross-correlation may introduce lagged time input components with errors owing to the assumption of linearity. Moreover, three other ML models: MLP, XGBoost, and KNN were coupled with the Boruta-XGBoost to validate the main hybrid framework for forecasting the daily EC values in 1-, 3-, 5-, 7-, and 10-month-ahead scenarios for the Barratta Creek and Albert River over the period of 2012 to 2021.

All the schemes were implemented in Python 3.60, based on the Keras, Scikit-learn, XGBoost, and Boruta-SHAP libraries. Figure 9 shows the process flow of the multi-step forecasting of the EC parameters. As discussed, the Boruta-XGBoost feature selection technique specifies an importance factor for each predictor, i.e., the Z-score56. If the Z-score is greater than the max-shadow (a benchmark criterion), the considered predictor is input to the ML models, and the predictors with Z-scores lower than the criterion are ignored57. Input pools including 20 lags of EC signals associated with both study areas in four horizons (i.e., 1-day, 3-day, 5-day, 7-day, and 10-day ahead) were assessed using the Boruta-XGBoost approach. Figures 7 and 8 show the results of the Boruta-XGBoost feature selection for the Albert River and Barratta Creek River, respectively. The green predictors are the significant components that pass the max-shadow condition, the red predictors are the rejected entities, and the yellow predictors are tentative entities. Table 2 lists the optimal lagged-time components to be fed to the ML models in the four horizons for each river.

It is necessary to use an appropriate strategy for splitting the time-series dataset for forecasting. Generally, approximately 60–80% of the dataset is used for training the models, and the rest is used for validation. To this end, cross-validation strategies such as k-fold cross-validation58, holdout, and walking-forward59 approaches are promising to avoid overfitting. In this study, the holdout strategy was used, with 70% and 30% of the dataset used for training and testing, respectively.

Four powerful ML models were used to forecast the daily EC: Boruta-XGB-MLP, Boruta-XGB-XGBoost, Boruta-XGB-KNN, and Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM (proposed). Notably, the hyperparameters in hybrid models must be appropriately tuned to avoid overfitting while obtaining the optimal modeling results. To this end, various free-source strategies such as grid search, random search, and Bayesian optimization can be applied and implemented in various programming languages such as MATLAB and Python60,61. In this research, the ML model is optimized using the grid search technique. Table 3 summarizes the optimal settings, network architecture, and hyperparameters associated with the four ML models. The key hyperparameters of the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM approach, as the model of interest, were the number of LSTM layers number, number of CNN layers, number of neurons, training algorithm, and learning rate62.

A pre-processing step, classical normalization, was applied to mitigate the negative effects of the data scale: All the inputs and targets were limited between zero and one. This operation is typically applied to increase the rate of convergence and modeling accuracy63.

Statistical metrics

Six statistical indices were used evaluate the robustness of the ML models: RMSE, correlation coefficient (R), uncertainty with a confidence level of 95% (\(U_{95\% }\)), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), T-statistic test (\(T_{stat}\)), and Nash–Sutcliffe model efficiency coefficient (NSE)60,61, expressed as follows:

where \(EC_{o,i }\) and \(EC_{p,i}\) are the measured and forecasted values of EC, respectively; \(\overline{{EC_{o } }}\) and \(\overline{{EC_{p} }}\) are the mean measured and forecasted values of EC, respectively; MBE is the mean bias error; and N is the length of the time series. The best and worst fitting between the measured and forecasted values of the EC occurs correspond to the following values: (R = 1, \(E\) = 1, MAPE = 0, RMSE = 0, and \(U_{95\% }\) = 0) and (R = 1, \(E\) = \(- \infty\), MAPE = \(\infty\), RMSE = \(\infty\), and \(U_{95\% }\) = \(\infty\)), respectively64,65.

Ethical approval

The manuscript is conducted in the ethical manner advised by the water resource management journal.

Consent to publish

The research is scientifically consented to be published.

Results and discussion

The forecasting ability of the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM, Boruta-XGB-MLP, Boruta-XGB-KNN, and Boruta-XGB-XGBoost models for multi-step ahead EC for the two Australian rivers was evaluated using the evaluation metrics (R, RMSE, MAPE, E, Tstat, and U95%) for the training and testing stages and diagnostic plots.

Table 4 presents the one-step ahead forecasting results of the four models for the Albert River at Bromfleet. The Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model outperformed the other models in the training (R = 0.9515, RMSE = 51.2558, MAPE = 5.9893, E = 0.9032, Tstat = 7.5962, U95% = 141.2955) and testing (R = 0.9429, RMSE = 45.6896, MAPE = 5.9749, E = 0.8878, Tstat = 3.3426, U95% = 126.3533) periods in the one-step-ahead EC forecasting for the Albert River. Boruta-XGB-XGBoost exhibited the second-best performance, followed by Boruta-XGB-MLP and Boruta-XGB-KNN based on the goodness-of-fit metrics.

Figure 10 shows the scatter plots for the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM and comparative models, incorporating the upper and lower bounds, in terms of the R and RMSE metrics between the measured and forecasted one-step-ahead EC (Albert River) in the testing period. The Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model exhibited the highest accuracy with R = 0.9429 and RMSE = 45.68, followed by XGBoost (R = 0.9323 and RMSE = 52.444), MLP (R = 0.9261 and RMSE = 52.777), and Boruta-XGB-KNN (R = 0.8302 and RMSE = 82.499). Furthermore, the forecast generated by the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model lay within the 25% upper and lower bound thresholds, indicating a strong relationship between the forecasted and measured EC.

Figure 11 shows the ridge plots, which indicate the relative deviation percent (RD, %) to assess the one-step-ahead EC forecasts for the Albert River obtained by the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM and comparative models. In addition, the interquartile range (IQR) values are presented. The Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model produced the most accurate RD distribution with the lowest IQR = 5.333. The benchmark Boruta-XGB-XGBoost model was superior to the Boruta-XGB-MLP and Boruta-XGB-KNN model.

Table 5 presents the one-step ahead forecasting results of the four models for Barratta Creek. The proposed Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model was slightly more accurate than the comparative models in the training period (R = 0.9316, RMSE = 43.2172, MAPE = 7.6428, E = 0.8673, Tstat = 2.7861, U95% = 119.7122) and testing period (R = 0.9215, RMSE = 43.8315, MAPE = 7.6029, E = 0.8488, Tstat = 1.1701, U95% = 121.4845). Although the performance of the comparative models was satisfactory, it was lower than that of the proposed approach in forecasting the one-step ahead EC for Barratta Creek.

Figure 12 shows the scatter plots for the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM and comparative models, incorporating the upper and lower bounds, in terms of the R and RMSE metrics between the measured and forecasted one-step-ahead EC (Barratta Creek). The Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model achieved the highest accuracy (R = 0.9215 and RMSE = 43.831), and the forecast lay within the 25% range between the upper and lower bound thresholds. The models ranking second, third, and fourth in terms of the accuracy were Boruta-XGB-MLP (R = 0.9184 and RMSE = 44.717), Boruta-XGB-XGBoost (R = 0.9128 and RMSE = 46.064), and Boruta-XGB-KNN (R = 0.9042 and RMSE = 48.315), respectively. Although the 25% upper and lower bounds were reasonable for the comparative models, the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM was the best model in this forecasting task.

Figure 13 shows the ridge plots for Barratta Creek to indicate the RD (%) errors and IQR values. Although all models exhibit reasonable RD (%) errors, the forecasts based on the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model are slightly more accurate with IQR = 10.30, followed by Boruta-XGB-MLP (IQR = 10.157), Boruta-XGB-KNN (IQR = 11.363), and Boruta-XGB-XGBoost (IQR = 11.873). Therefore, the proposed model yields the most accurate one-step-ahead EC forecasts for Barratta Creek.

Figure 14 shows the Taylor diagram of the one-step-ahead EC forecasted by the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM, MLP, KNN, and XGBoost models for (A) Albert River and (B) Barratta Creek. The Taylor diagram is a valuable tool for comprehensively assessing the model's comparability against the observed EC using the standard deviation and correlation coefficient. For Albert River, the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM (blue solid circle) forecast was close to the measured EC, with a correlation coefficient of more than 0.95 and standard deviation ranging between 125 and 150. The Boruta-XGB-MLP, Boruta-XGB-KNN, and Boruta-XGB-XGBoost predictions were slightly far from the measured EC with a correlation coefficient lower than 0.95 and standard deviation ranging between 100 and 150. For Barratta Creek, the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM (red solid circle) model exhibited the highest precision with a correlation coefficient of 0.90–0.95, followed by the Boruta-XGB-MLP, Boruta-XGB-XGBoost, and Boruta-XGB-KNN models. In other words, the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model was superior in forecasting the one-step ahead EC for both Albert River and Barratta Creek.

Multi-step ahead forecasting

Table 6 presents the metrics for the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM multi-step ahead forecasts (i.e., 3-, 5-, 7-, and 10-day-ahead) EC for Albert River. The forecasting accuracy in the 3-day-ahead scenario was higher than that for the 7- and 10-day-ahead cases in both the training and testing periods, as indicated by the superior goodness-of-fit metrics for the 3-day-ahead forecasts: (R = 0.8947, RMSE = 73.6800, MAPE = 10.4113, E = 0.7998, Tstat = 2.3851, U95% = 204.1362) for the training period and (R = 0.8764, RMSE = 66.3651, MAPE = 12.0275, E = 0.7633, Tstat = 4.7504, U95% = 183.0642) for the testing period. Similarly, the 5-day-ahead was superior to that of the 7- and 10-day-ahead forecasts but inferior to that of the 3-day-ahead horizon. In other words, the proposed model attained a higher precision in short-term forecasting (i.e., 1-, 3-, and 5-day) compared with that for long-term forecasting (i.e., 7- and 10-day) of the EC for Albert River.

Figure 15 shows the scatterplots along with the R and RMSE metrics of the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model for multi-step ahead (i.e., 3-, 5-, 7-, and 10-day) EC forecasts for the Albert River. In addition, the 25% upper and lower bound confidence intervals are presented. The strongest correlation is observed for the 3-day-ahead EC forecasts, given the highest R (0.8764) and lowest RMSE (66.365), although the forecasts for the 5-, 7-, and 10-day-ahead EC forecasts are also satisfactory. Overall, the proposed model is better at short-term EC forecasting (1-, 3-, and 5-day), and the performance decreases over long-term forecast horizons (i.e., 7- and 10-day) for the Albert River.

Table 7 and Fig. 16 present the multi-step ahead (i.e., 3-, 5-, 7-, and 10-day) EC forecasts for Barratta Creek obtained using the proposed Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model. Table 7 shows that the model yields more accurate forecasts in the 3- and 5-day-ahead horizon compared with the 7- and 10-day-ahead horizons in the training and testing periods. This finding is supported by the scatter plots in Fig. 16. The short-term forecasts (3- and 5-day-ahead) are more accurate (R of 0.7677 and 0.7108, respectively) with lower RMSEs (72.466 and 79.445, respectively) compared with those of the 7- and 10-day-ahead horizons. Therefore, the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model is more effective for short-term EC forecasting in Barratta Creek station.

Discussion

The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model in accurately forecasting EC for the Albert River and Barratta Creek across different time horizons. For predictions from one day ahead, the hybrid model outperformed other ML approaches according to multiple statistical evaluation metrics. This indicates the benefits of optimizing input features and leveraging CNN-LSTM architectures for water quality prediction. Notably, short-term forecasts up to 5 days achieved higher accuracy than longer 7–10-day horizons. This is understandable, given the increasing uncertainty for more distant predictions. However, the model still produced reasonably good accuracy even 10 days ahead, suggesting usefulness for supporting various planning functions. While performance decreased with lead time as expected, the slight deterioration demonstrates the model's ability to learn dependencies beyond immediate observations. This capacity to capture rich temporal patterns should aid in addressing non-stationarities in environmental systems. Comparing performance across stations reveals the approach is transferable despite rivers' differing characteristics. Tests on independent sites within Australia indicate potential for applicability in diverse settings pending location-specific tuning. The study’s findings have several potential applications and implications for improving water resource management and environmental monitoring. The accurate multi-step electrical conductivity forecasts produced by the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model allow river authorities to optimize water allocation and reservoir operations over different timescales. This helps balance the needs of water users. The model's predictions also help pollution control agencies identify at-risk areas and implement targeted mitigation strategies. Meanwhile, drinking water facilities and industries can better treat incoming supplies if alerted in advance about changing EC levels via the forecasts. Agricultural producers and fish farmers could also utilize the projections to schedule irrigation and select suitable crops/species. Furthermore, the predictions may aid emergency responders during flood and contamination events. Overall, systematically incorporating data-driven insights enables the development of long-term, sustainable river basin management strategies while considering both current and future water quality conditions. The reliable, AI-powered monitoring and forecasting capabilities also support compliance with environmental regulations over time.

Conclusion

A hybrid CNN-LSTM model was used to forecast multi-step ahead EC for the Albert River and Barratta Creek in Australia. The proposed model was optimized using the Boruta-XGBoost algorithm to rank and select the best input features. Forecasting was performed over the 1-, 3-, 5-, 7-, and 10-day horizons to demonstrate the applicability of the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model. Moreover, the forecasting performance of the proposed method was compared with those of the state-of-the-art models: Boruta-XGB-MLP, Boruta-XGB-XGBoost, and Boruta-XGB-KNN. The goodness-of-fit metrics demonstrated that the hybrid Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM could effectively forecast the multi-step ahead EC for both rivers. In particular, the proposed model attained the highest precision in the testing period for the Albert River (R = 0.9429, RMSE = 45.6896, MAPE = 5.9749, E = 0.8878, Tstat = 3.3426, U95% = 126.3533) and Barratta Creek (R = 0.9215, RMSE = 43.8315, MAPE = 7.6029, E = 0.8488, Tstat = 1.1701, U95% = 121.4845) in forecasting one-step ahead EC. Moreover, the Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM was more accurate in short-term (i.e., 1-, 3-, and 5-day) forecasting, and its performance slightly deteriorated in the 7- and 10-day-ahead forecast horizons. The proposed model can be extended to other applications such as agriculture, environmental, and atmospheric modeling.

While the proposed Boruta-XGB-CNN-LSTM model achieved good performance, some limitations still exist. The study utilized daily water quality and meteorological data from only two rivers within Australia, so expanding data collection from more diverse locations globally would help validate the generalizability and robustness of models. Additionally, additional real-time data sources like satellite imagery could help capture spatial influences and improve forecasts. The study focused on predicting a single water quality parameter but developing multi-parameter models that simultaneously forecast other important indices would increase practical relevance. Moreover, while measures were taken to prevent overfitting, more rigorous validation techniques like uncertainty quantification on out-of-sample data could provide a realistic assessment of long-term forecast accuracy. Addressing these limitations through multidisciplinary collaborations in future work would help advance the development of widely applicable AI solutions for integrated water resource and ecosystem management globally.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

09 August 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69309-3

References

Tierno-de-Figueroa, J. M., López-Rodríguez, M. J., Fenoglio, S., Sánchez-Castillo, P. & Fochetti, R. Freshwater biodiversity in the rivers of the Mediterranean Basin. Hydrobiologia 719, 137–186 (2013).

Debnath, A., Singh, P. K. & Sharma, Y. C. Metallic contamination of global river sediments and latest developments for their remediation. J. Environ. Manage. 298, 113378 (2021).

Jones, R. G. Measurements of the electrical conductivity of water. IEEE Proc. Sci. Meas. Technol. 149, 320–322 (2002).

Ahmadianfar, I., Shirvani-Hosseini, S., He, J., Samadi-Koucheksaraee, A. & Yaseen, Z. M. An improved adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system model using conjoined metaheuristic algorithms for electrical conductivity prediction. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–34 (2022).

Wilcox, L. V. The Quality of Water for Irrigation Use (Springer, 1948).

McNeely, R. N., Neimanis, V. P. & Dwyer, L. Water quality sourcebook. A guide to water quality parameters. In 1979 89 p, 6 fig, 8 tab, 38 ref, 1 append (1979).

Wu, J. & Wang, Z. A hybrid model for water quality prediction based on an artificial neural network, wavelet transform, and long short-term memory. Water 14, 610 (2022).

Jamei, M., Ahmadianfar, I., Chu, X. & Yaseen, Z. M. Prediction of surface water total dissolved solids using hybridized wavelet-multigene genetic programming: New approach. J. Hydrol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125335 (2020).

Tiyasha-Tung, T. M. & Yaseen, Z. M. A survey on river water quality modelling using artificial intelligence models: 2000–2020. J. Hydrol. 585, 124670 (2020).

United Nations. Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal6 (2022).

Obaideen, K. et al. Biogas role in achievement of the sustainable development goals: Evaluation, challenges, and guidelines. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 131, 104207 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. Characterizing the river water quality in China: Recent progress and on-going challenges. Water Res. 201, 117309 (2021).

Mănoiu, V.-M. & Crăciun, A.-I. Danube river water quality trends: A qualitative review based on the open access web of science database. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2021, 859 (2021).

Asadollah, S. B. H. S., Sharafati, A., Motta, D. & Yaseen, Z. M. River water quality index prediction and uncertainty analysis: A comparative study of machine learning models. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 104599 (2021).

Al-Sulttani, A. O. et al. Proposition of new ensemble data-intelligence models for surface water quality prediction. IEEE Access 9, 108521 (2021).

Giri, S. & Qiu, Z. Understanding the relationship of land uses and water quality in Twenty First Century: A review. J. Environ. Manage. 173, 41–48 (2016).

Yaseen, Z. M. A new benchmark on machine learning methodologies for hydrological processes modelling: A comprehensive review for limitations and future research directions. Knowl.-Based Eng. Sci. 4, 65–103 (2023).

Giri, S. Water quality prospective in twenty first century: Status of water quality in major river basins, contemporary strategies and impediments: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 116332 (2020).

Tiyasha, T., Tung, T. M. & Yaseen, Z. M. Deep learning for prediction of water quality index classification: Tropical catchment environmental assessment. Nat. Resour. Res. 2021, 1–20 (2021).

Jamei, M. et al. The assessment of emerging data-intelligence technologies for modeling Mg+ 2 and SO4− 2 surface water quality. J. Environ. Manage. 300, 113774 (2021).

Tiyasha, T. et al. Functionalization of remote sensing and on-site data for simulating surface water dissolved oxygen: Development of hybrid tree-based artificial intelligence models. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 170, 112639 (2021).

Swagatika, S., Paul, J. C., Sahoo, B. B., Gupta, S. K. & Singh, P. K. Improving the forecasting accuracy of monthly runoff time series of the Brahmani River in India using a hybrid deep learning model. J. Water Clim. Chang. 15, 139–156 (2024).

Sahoo, B. B., Panigrahi, B., Nanda, T., Tiwari, M. K. & Sankalp, S. Multi-step ahead urban water demand forecasting using deep learning models. SN Comput. Sci. 4, 752 (2023).

Sahoo, B. B., Sankalp, S. & Kisi, O. A novel smoothing-based deep learning time-series approach for daily suspended sediment load prediction. Water Resour. Manag. 37, 4271–4292 (2023).

Zhi, W. et al. From hydrometeorology to river water quality: Can a deep learning model predict dissolved oxygen at the continental scale?. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 2357–2368 (2021).

Sharma, P. & Sahoo, B. B. Precise prediction of performance and emission of a waste derived Biogas-Biodiesel powered Dual-Fuel engine using modern ensemble Boosted regression Tree: A critique to Artificial neural network. Fuel 321, 124131 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Concentration estimation of dissolved oxygen in Pearl River Basin using input variable selection and machine learning techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 731, 139099 (2020).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Kursa, M. B., Jankowski, A. & Rudnicki, W. R. Boruta—a system for feature selection. Fundam. Informat. 101, 271–285 (2010).

Yuan, X. et al. A novel feature susceptibility approach for a PEMFC control system based on an improved XGBoost-Boruta algorithm. Energy AI 2023, 100229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyai.2023.100229 (2023).

Kursa, M. B., Jankowski, A. & Rudnicki, W. R. Boruta–a system for feature selection. Fundam. Informat. 101, 271–285 (2010).

Sabour, M. R., Besharati, M., Dezvareh, G. A., Hajbabaie, M. & Akbari, M. Application of artificial neural network with the back-propagation algorithm for estimating the amount of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Tehran Oil Refinery, Iran. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 18, 100677 (2022).

Akbari, M., Salmasi, F., Arvanaghi, H., Karbasi, M. & Farsadizadeh, D. Application of Gaussian process regression model to predict discharge coefficient of Gated Piano Key Weir. Water Resour. Manag. 33, 3929–3947 (2019).

Rehamnia, I., Benlaoukli, B., Jamei, M., Karbasi, M. & Malik, A. Simulation of seepage flow through embankment dam by using a novel extended Kalman filter based neural network paradigm: Case study of Fontaine Gazelles Dam, Algeria. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2021.109219 (2021).

Jamei, M. et al. Air quality monitoring based on chemical and meteorological drivers: Application of a novel data filtering-based hybridized deep learning model. J. Clean. Prod. 374, 134011 (2022).

Lima, A. R., Cannon, A. J. & Hsieh, W. W. Forecasting daily streamflow using online sequential extreme learning machines. J. Hydrol. 537, 431–443 (2016).

Deo, R. C. et al. Multi-layer perceptron hybrid model integrated with the firefly optimizer algorithm for windspeed prediction of target site using a limited set of neighboring reference station data. Renew. Energy 116, 309–323 (2018).

Khoshbin, F. et al. Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system multi-objective optimization using the genetic algorithm/singular value decomposition method for modelling the discharge coefficient in rectangular sharp-crested side weirs. Eng. Optim. 48, 933–948 (2016).

Chen, T., He, T., Benesty, M., Khotilovich, V. & Tang, Y. Xgboost: Extreme gradient boosting. R Packag. version 0.4-2 1–4 (2015).

Bhagat, S. K., Tiyasha, T., Tung, T. M., Mostafa, R. R. & Yaseen, Z. M. Manganese (Mn) removal prediction using extreme gradient model. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 204, 111059 (2020).

Fan, J., Wu, L., Zheng, J. & Zhang, F. Medium-range forecasting of daily reference evapotranspiration across China using numerical weather prediction outputs downscaled by extreme gradient boosting. J. Hydrol. 601, 12664 (2021).

Ni, L. et al. Streamflow forecasting using extreme gradient boosting model coupled with Gaussian mixture model. J. Hydrol. 2020, 124901 (2020).

Osman, A. I. A., Ahmed, A. N., Chow, M. F., Huang, Y. F. & El-Shafie, A. Extreme gradient boosting (Xgboost) model to predict the groundwater levels in Selangor Malaysia. Ain Shams Eng. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2020.11.011 (2021).

Khanifar, J. & Khademalrasoul, A. Modeling of land surface temperature–multiscale curvatures relationship using XGBoost algorithm (Case study: Southwestern Iran). Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19, 11763–11774 (2022).

Ben-Jabeur, S., Stef, N. & Carmona, P. Bankruptcy prediction using the XGBoost algorithm and variable importance feature engineering. Comput. Econ. 2022, 1–27 (2022).

Altman, N. S. An Introduction to Kernel and Nearest-Neighbor Nonparametric Regression. Am. Stat. 46, 175–185 (1992).

Livieris, I. E., Pintelas, E. & Pintelas, P. A CNN–LSTM model for gold price time-series forecasting. Neural Comput. Appl. 32, 17351–17360 (2020).

Wei, Z. & Liu, Y. Construction of super-resolution model of remote sensing image based on deep convolutional neural network. Comput. Commun. 178, 191–200 (2021).

Zhu, J., Chen, H. & Ye, W. A hybrid CNN–LSTM network for the classification of human activities based on micro-Doppler radar. IEEE Access 8, 24713–24720 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Miyamori, Y., Mikami, S. & Saito, T. Vibration-based structural state identification by a 1-dimensional convolutional neural network. Comput. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 34, 822–839 (2019).

Li, L. et al. Prediction of TBM cutterhead speed and penetration rate for high-efficiency excavation of hard rock tunnel using CNN-LSTM model with construction big data. Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 1–17 (2022).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1–32 (1997).

Graves, A. Generating sequences with recurrent neural networks. arXiv Prepr. arXiv1308.0850 (2013).

Bhattarai, A., Qadir, D., Sunusi, A. M., Getachew, B. & Mallah, A. R. Dynamic sliding window-based long short-term memory model development for pan evaporation forecasting. Knowl.-Based Eng. Sci. 4, 37–54 (2023).

Elsayed, S. et al. Interpretation the influence of hydrometeorological variables on soil temperature prediction using the potential of deep learning model. Knowl.-Based Eng. Sci. 4, 55–77 (2023).

Jamei, M. et al. Computational assessment of groundwater salinity distribution within coastal multi-aquifers of Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–28 (2022).

Malik, A. et al. Multi-step daily forecasting of reference evapotranspiration for different climates of India: A modern multivariate complementary technique reinforced with ridge regression feature selection. Agric. Water Manag. 272, 107812 (2022).

Jamei, M. et al. Long-term multi-step ahead forecasting of root zone soil moisture in different climates: Novel ensemble-based complementary data-intelligent paradigms. Agric. Water Manag. 269, 107679 (2022).

Gao, R., Du, L., Yuen, K. F. & Suganthan, P. N. Walk-forward empirical wavelet random vector functional link for time series forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 108, 107450 (2021).

Jamei, M. et al. Development of a TVF-EMD-based multi-decomposition technique integrated with encoder-decoder-bidirectional-LSTM for monthly rainfall forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2023, 129105 (2023).

Jamei, M. et al. Development of wavelet-based Kalman Online Sequential Extreme Learning Machine optimized with Boruta-Random Forest for drought index forecasting. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 117, 105545 (2023).

Sharma, E. et al. Novel hybrid deep learning model for satellite based PM10 forecasting in the most polluted Australian hotspots. Atmos. Environ. 279, 119111 (2022).

Karbasi, M., Jamei, M., Ali, M., Malik, A. & Yaseen, Z. M. Forecasting weekly reference evapotranspiration using Auto Encoder Decoder Bidirectional LSTM model hybridized with a Boruta-CatBoost input optimizer. Comput. Electron. Agric. 198, 107121 (2022).

Nash, J. E. & Sutcliffe, J. V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—a discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 10, 282–290 (1970).

Pan, T., Wu, S., Dai, E. & Liu, Y. Estimating the daily global solar radiation spatial distribution from diurnal temperature ranges over the Tibetan Plateau in China. Appl. Energy 107, 384–393 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K, M.A, S.B, C.J, M.J, A.F, and Z.Y wrote the main manuscript text. Z.Y prepared Fig 1. M.J plotted Figs 6 and 9. M.K plotted Figs 1-5 and 7-16. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, Changhyun Jun and Aitazaz Ahsan Farooque were omitted as corresponding authors. The correct corresponding authors for this Article are Masoud Karbasi, Changhyun Jun and Aitazaz Ahsan Farooque.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karbasi, M., Ali, M., Bateni, S.M. et al. Multi-step ahead forecasting of electrical conductivity in rivers by using a hybrid Convolutional Neural Network-Long Short-Term Memory (CNN-LSTM) model enhanced by Boruta-XGBoost feature selection algorithm. Sci Rep 14, 15051 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65837-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65837-0