Abstract

Density functional theory calculations are carried out to investigate the adsorption properties of Li+ and Li on twenty-four adsorbents obtained by replacement of C atoms of coronene (C24H12) and circumcoronene (C54H18) by Si/N/BN/AlN units. The molecular electrostatic potential (MESP) analysis show that such replacements lead to an increase of the electron-rich environments in the molecules. Li+ is relatively strongly adsorbed on all adsorbents. The adsorption energy of Li+ (Eads-1) on all adsorbents is in the range of − 42.47 (B12H12N12) to − 66.26 kcal/mol (m-C22H12BN). Our results indicate a stronger interaction between Li+ and the nanoflakes as the deepest MESP minimum of the nanoflakes becomes more negative. A stronger interaction between Li+ and the nanoflakes pushes more electron density toward Li+. Li is weakly adsorbed on all adsorbents when compared to Li+. The adsorption energy of Li (Eads-2) on all adsorbents is in the range of − 3.07 (B27H18N27) to − 47.79 kcal/mol (C53H18Si). Assuming the nanoflakes to be an anode for the lithium-ion batteries, the cell voltage (Vcell) is predicted to be relatively high (> 1.54 V) for C24H12, C12H12Si12, B12H12N12, C27H18Si27, and B27H18N27. The Eads-1 data show only a small variation compared to Eads-2, and therefore, Eads-2 has a strong effect on the changes in Vcell.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is an increasing demand for rechargeable energy storage devices such as lithium ion batteries (LIBs) for their application in portable electronic devices and electric vehicles1,2,3. Since LIBs were first commercialized by Sony Corporation in the 1990s, they have occupied a dominant position in the portable electronics and automobile markets because of their high energy density and long service life1,2,3. Carbon materials such as graphene, carbon nanotube, carbon nanofiber, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) are widely used to construct anode materials in LIBs4,5,6,7,8,9. For example, graphene, a two-dimensional sheet of sp2-hybridized carbon atoms, has been proved to be a good electrode material for LIBs owing to its high surface area, high electrical conductivity, and superior mechanical flexibility. Doped carbonaceous materials were also used to construct anode materials in LIBs10,11,12,13,14.

PAHs are composed of two or more fused benzene rings and have many delocalized π electrons. Researchers have designed and synthesized various heteroatom-embedded PAHs to modify the π-electron properties15,16,17. Planar PAHs such as coronene (C24H12) and circumcoronene (C54H18) consist of seven and nineteen fused benzene rings, respectively. They can be considered as small portions of a graphene sheet with hydrogenated edges. There have been DFT studies on the adsorption properties of coronene, circumcoronene and their doped analogues18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. The presence of silicon atoms in coronene favored its interaction with thiophene and similar compounds18. The hydrophobic ionic liquid adsorption on coronene and circumcoronene was stronger than that for the hydrophilic ionic liquid19. The free energy of adsorption of ionic liquids on BN-circumcoronene (B27H18N27) was negative, and thus, the adsorption occurred spontaneously20. The adsorption of organic molecules on Cu-doped coronene and circumcoronene was exothermic21. The relative positions of nitrogen and boron substitutions in the coronene gave different stabilities and different responses to the CO adsorption22. The interaction energies usually increased with the cluster size of the palladium atoms adsorbed on the coronene23. The doping of coronene with nitrogen atoms resulted in superior performance for CO2 and H2 adsorption24. The DFT studies on the adsorption of Li+ and Li on coronene, circumcoronene and BN-circumcoronene have recently attracted increasing interest. It was found that Li+/Li binds to the peripheral rings of coronene and circumcoronene25,26,27. Based on the cell voltage data, coronene was suggested as a good anode material for LIBs27. The adsorption energy of Li atom on B27H18N27 was found to be lower than that of circumcoronene28. However, the adsorption of Li+ and Li on adsorbents such as BN doped coronene is yet to be studied.

In this work, DFT calculations are performed to investigate the adsorption properties of Li+ and Li on twenty-four adsorbents obtained by replacement of C atoms of C24H12 and C54H18 by Si/N/BN/AlN units. The most-negative valued molecular electrostatic potential (MESP) point of molecules (Vmin) indicates the electron-rich regions such as π-region and lone-pair region31,32. A key observation is that the adsorption energies of Li+ on the nanoflakes are linearly correlated with the MESP Vmin values of the nanoflakes. The Vcell is predicted to be relatively high (> 1.54 V) for C24H12, C12H12Si12, B12H12N12, C27H18Si27, and B27H18N27 The insights obtained from this work may be useful to design and explore better anode materials for LIBs.

Computational details

All the DFT calculations were performed using the Gaussian 16 code33. In this work we consider a total of twenty-four adsorbents (C24H12 and its analogues C23H12Si, o-C22H12N2, m-C22H12N2, m-C22H12BN, p-C22H12BN, C20H12B2N2, C18H12B3N3, C16H12Si8, C12H12Si12, B12H12N12, B11H12N12Al; C54H18 and its analogues C53H18Si, o-C52H18N2, m-C52H18N2, m-C52H18BN, p-C52H18BN, C50H18B2N2, C48H18B3N3, C36H18Si18, C27H18Si27, B27H18N27, B26H18N27Al) and two adsorbates (Li+ and Li). The other adsorbents are designed by the replacements of C atoms in coronene and circumcoronene by Si/N/BN/AlN units. Here we also employed structural isomers of, for example, C22H12N2 (the two N atoms occupy adjacent positions in o-C22H12N2). Furthermore, C16H12Si8, C12H12Si12, and B12H12N12 can be considered as small portions of SiC2, SiC, and BN graphene-like sheets, respectively. The same applies to C36H18Si18, C27H18Si27, and B27H18N27. All structures were optimized at the M062X/6-31G(d,p) level34 and confirmed to be energy minima by frequency analysis. The MESP function V(r)35,36,37 is computed at the M062X/6-31G(d,p) level of theory using the below equation:

where ZA is the charge on nucleus A located at RA and ρ(r) is the electronic charge density. The first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (1) stands for the nuclear contribution and the second term stands for the electronic contribution. V(r) is positive if the nuclear effects dominate, while it is negative if the electronic effects dominate.

The adsorption energy (Eads) is evaluated according to the formula:

where Eadsorbate/nanoflake, Enanoflake, and Eadsorbate represent the energy of adsorbed system, adsorbent (e.g., coronene), and adsorbate (Li+ or Li), respectively. EBSSE is the basis set superposition error energy determined by the counterpoise approach38. The Eads of Li+ and Li on the nanoflakes is represented as Eads-1 and Eads-2, respectively. Our calculated Eads-1 and Eads-1 values are consistent with previous results26,27,28 (Fig. 1).

The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO)-lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy gap (Eg) is calculated as follows:

where EHOMO and ELUMO represent the energy of HOMO and LUMO, respectively. The Eg of the pristine nanoflakes, Li+-adsorbed nanoflakes, and Li-adsorbed nanoflakes is represented as Eg-1, Eg-2, and Eg-3, respectively.

The percentage change in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap is estimated as:

Assuming the nanoflake to be an anode for the LIBs, we can write the reaction in the anode and cathode as follows:

Thus, the total cell reaction can be written as follows:

Here ∆Gcell is the Gibbs free energy change for the total cell reaction, which can be expressed as

where

The cell voltage can be calculated using the Nernst equation:

where F and z are the Faraday constant (96,485.3 C/mol) and the charge of Li+, respectively. It may be assumed that ΔGcell ≈ ΔEcell, since the contribution of entropy and volume effects to Vcell is expected to be very small39.

Results and discussion

Coronene and its analogues as anode materials in lithium-ion batteries

Structural properties of coronene and its analogues

The optimized structures of coronene and its analogues are given in Fig. 2, indicating all the important bond length values. The XY (X = C, Si, N, B, Al; Y = C, Si, N, B, Al) bond lengths of coronene and its analogues are in the range of about 1.35 to 1.81 Å. In comparison to the CC bond length in benzene (1.395 Å)40, we see that the CC bond lengths in coronene are in the range of about 1.37 to 1.43 Å. The six outermost CC bonds in coronene are noticeably shorter (1.37 Å) than the other ones. Their bond lengths are close to the CC bond length in ethylene (1.330 Å)41, indicating the significant double bond character of these bonds. Here the CSi (> 1.73 Å) and NAl (> 1.74 Å) bond lengths are found to be significantly longer than all the CC bond lengths in coronene.

Optimized structures of (a) C24H12, (b) C23H12Si, (c) o-C22H12N2, (d) m-C22H12N2, (e) m-C22H12BN, (f) p-C22H12BN, (g) C20H12B2N2, (h) C18H12B3N3, (i) C16H12Si8, (j) C12H12Si12, (k) B12H12N12, (l) B11H12N12Al. The bond distances are given in Å. Color code: gray-C, green-B, blue-N, purple-Al, yellow-Si.

The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-1 values of coronene and its analogues are given in Table 1. The molecular orbital diagrams for some representative nanoflakes are shown in Fig. S1. Our results show that the EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-1 values of coronene and its analogues are in the ranges of − 8.27 (B12H12N12) to − 3.82 eV (m-C22H12N2), − 1.43 (p-C22H12BN) to 1.24 eV (B12H12N12), and 2.95 (m-C22H12N2) to 9.51 eV (B12H12N12), respectively. The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-1 values of coronene are − 6.62, − 0.72, and 5.90 eV, respectively. In general, the EHOMO (ELUMO) of the doped coronene is higher (lower) than that of the pristine coronene. Also, the Eg-1 of the doped coronene is generally lower than that of the pristine coronene. The opposite trends are observed for the B12H12N12 and B11H12N12Al. Typically, a smaller HOMO–LUMO energy gap indicates a better electronic conductivity. These EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-1 values reported here are consistent with previous theoretical results29.

MESP of coronene and its analogues

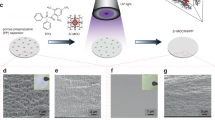

The MESP features of coronene and its analogues are given in Fig. 3. The MESP analysis suggest that electron-rich regions (e.g., green regions) are present on coronene due to cyclic π-electron delocalization. We see that the replacements of C atoms of coronene by Si/N/BN/AlN units lead to an overall increase of the electron-rich environments (e.g., blue regions) in the molecules. The MESP Vmin values of coronene and its analogues (represented as Vmin) are provided in Table 1. The locations of Vmin in the MESP plots of coronene and its analogues are provided in Fig. S2, electronic Supporting Information (ESI). The MESP Vmin points are located near the peripheral rings of coronene. This shows that the peripheral rings of coronene are electron richer than its central ring. This is because the peripheral rings of coronene contain C–H bonds also and the sp2 carbon is more electronegative than H. For other adsorbents also, the MESP Vmin points are located near the peripheral rings. We find that the MESP Vmin values of coronene and its analogues are in the range of − 15.44 (C18H12B3N3) to − 31.38 kcal/mol (m-C22H12BN). The MESP Vmin value of coronene is − 16.06 kcal/mol. The MESP Vmin of the doped coronene is generally higher than that of the pristine coronene. However, the MESP Vmin of C18H12B3N3 is slightly lower than that of coronene. For the N-doped coronenes, the MESP Vmin value of o-C22H12N2 (− 24.22 kcal/mol) is higher than that of m-C22H12N2 (− 21.34 kcal/mol). The MESP Vmin values of Si-doped coronenes increase in the order C23H12Si < C12H12Si12 < C16H12Si8. Furthermore, the MESP Vmin values of BN/AlN-doped coronenes increase in the order C18H12B3N3 < B12H12N12 < B11H12N12Al < C20H12B2N2 < p-C22H12BN < m-C22H12BN.

MESP mapped on 0.01 a.u. electron density isosurface of (a) C24H12, (b) C23H12Si, (c) o-C22H12N2, (d) m-C22H12N2, (e) m-C22H12BN, (f) p-C22H12BN, (g) C20H12B2N2, (h) C18H12B3N3, (i) C16H12Si8, (j) C12H12Si12, (k) B12H12N12, (l) B11H12N12Al. The colour coding from blue to red indicates MESP values in the range − 0.03 to 0.03 a.u. The colours at the blue end of the spectrum indicate the electron-rich regions, while those toward the red indicate the electron-deficient regions.

Li+ adsorption on the doped coronenes

The optimized geometries for the adsorption of Li+ on coronene and its analogues are provided in Fig. 4. Our results show that Li+ binds to the peripheral rings of coronene. This is in line with the fact the peripheral rings of coronene are electron richer than its central ring (see above). The adsorption process here involves the cation–π interaction27,42. This interaction is basically of electrostatic origin because a positively charged cation interacts with the negatively charged electron cloud of π-systems. For other adsorbents also, Li+ binds to the peripheral rings. It can be seen that Li+ is relatively strongly adsorbed on coronene and its analogues. For example, the adsorption distance of Li+ on these adsorbents is in the range of 2.15 (C16H12Si8) to 2.34 Å (C12H12Si12). This observation is further supported by the adsorption energy of Li+ on coronene and its analogues (Table 2). The Eads-1 values of Li+ on coronene and its analogues are in the range of − 42.47 (B12H12N12) to − 66.26 kcal/mol (m-C22H12BN). These Eads-1 values are negative, which implies that all of the adsorption processes were exothermic in nature. The more negative the Eads-1 value, the stronger the adsorption is. The Eads-1 value of Li+ on coronene is − 47.92 kcal/mol. For the N-doped coronenes, the Eads-1 value of o-C22H12N2 (− 57.33 kcal/mol) is higher than that of m-C22H12N2 (− 54.48 kcal/mol). The Eads-1 values of Si-doped coronenes increase in the order C12H12Si12 < C23H12Si < C16H12Si8. Furthermore, the Eads-1 values of BN/AlN-doped coronenes increase in the order B12H12N12 < C18H12B3N3 < B11H12N12Al < C20H12B2N2 < p-C22H12BN < m-C22H12BN. A key observation is that these adsorption energies are well correlated with the MESP Vmin values of coronene and its analogues, with a correlation coefficient of 0.908 (Fig. 5a). These results indicate a stronger interaction between Li+ and the nanoflakes as the MESP Vmin of the nanoflakes becomes more negative.

Optimized structures of Li+ adsorbed on (a) C24H12, (b) C23H12Si, (c) o-C22H12N2, (d) m-C22H12N2, (e) m-C22H12BN, (f) p-C22H12BN, (g) C20H12B2N2, (h) C18H12B3N3, (i) C16H12Si8, (j) C12H12Si12, (k) B12H12N12, (l) B11H12N12Al. The bond distances are given in Å. The color code is the same as in Fig. 2. In addition, Li is denoted by orange color.

The electron donation from coronene and its analogues to Li+ could be checked by assessing the changes in the MESP at the nucleus of Li+ upon adsorption. Hence, the ΔVMESP-1 was obtained by taking the difference between the MESP at the nucleus of Li+ in the Li+-adsorbed nanoflake and the MESP at the free Li+ (− 5.36 au). Here the negative values of ΔVMESP-1 (Table 2) indicate the electron donation from coronene and its analogues to Li+. These ΔVMESP-1 values are in the range of − 105.91 (B12H12N12) to − 138.49 kcal/mol (m-C22H12N2). The ΔVMESP-1 value of coronene is − 107.01 kcal/mol. The ΔVMESP-1 of the doped coronenes is typically higher than that of the pristine coronene. However, the ΔVMESP-1 of B12H12N12 is lower than that of coronene. The adsorption energies of Li+ on coronene and its analogues are correlated with these ΔVMESP-1 values, with a correlation coefficient of 0.792 (Fig. 5b). These results indicate that a stronger interaction between Li+ and the nanoflakes pushes more electron density toward Li+.

The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-2 values of Li+-adsorbed coronene and its analogues are given in Table 2. The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-2 values of Li+-adsorbed coronene and its analogues are in the ranges of − 11.37 (B12H12N12) to − 8.18 eV (m-C22H12N2), − 5.06 (C23H12Si) to − 4.20 eV (C12H12Si12), and 3.73 (m-C22H12N2) to 7.04 eV (B12H12N12), respectively. Here, EHOMO of the Li+-adsorbed nanoflakes is lower than that of the pristine nanoflakes for all cases (see Table 1). A similar result is obtained for ELUMO. The results here show that Eg-2 is typically lower than Eg-1. For example, the EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-2 values of Li+ adsorbed coronene are − 10.05, − 4.38, and 5.67 eV, respectively. The decrease in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap for the adsorption of Li+ on coronene is 3.87% (see ΔEg-1 values in Table 2). A maximum decrease in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap of 26.0% was observed for the adsorption of Li+ on B12H12N12. However, Eg-2 is found to be higher than Eg-1 for the adsorption of Li+ on o-C22H12N2, m-C22H12N2, m-C22H12BN, p-C22H12BN, and C16H12Si8. A maximum increase in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap of 26.3% was observed for the adsorption of Li+ on m-C22H12N2.

Li adsorption on the doped coronenes

The optimized geometries for the adsorption of Li on coronene and its analogues are provided in Fig. 6. Our results show that Li mostly binds to the peripheral rings of coronene and its analogues, similar to the results obtained for Li+. The adsorption distance of Li on these adsorbents is in the range of 2.01 (o-C22H12N2) to 2.44 Å (B12H12N12). For these adsorbents, the adsorption distance of Li is generally smaller than that of Li+ (see Fig. 4). For example, the adsorption distance of Li and Li+ on coronene is 2.15 and 2.28 Å, respectively. However, Li is weakly adsorbed on coronene and its analogues when compared to Li+. This observation is supported by the adsorption energy of Li on coronene and its analogues (Table 3). The Eads-2 values of Li on coronene and its analogues are in the range of − 3.14 (B12H12N12) to − 37.63 kcal/mol (p-C22H12BN). The Eads-2 value of Li on coronene is − 11.32 kcal/mol. For the N-doped coronenes, the Eads-2 value of o-C22H12N2 (− 29.75 kcal/mol) is higher than that of m-C22H12N2 (− 23.69 kcal/mol). The Eads-2 values of Si-doped coronenes increase in the order C12H12Si12 < C16H12Si8 < C23H12Si. Furthermore, the Eads-2 values of BN/AlN-doped coronenes increase in the order B12H12N12 < C18H12B3N3 < B11H12N12Al < C20H12B2N2 < m-C22H12BN < p-C22H12BN. These adsorption energies are not well correlated with the MESP Vmin values of coronene and its analogues (Fig. S3). The ΔVMESP-2 was obtained by taking the difference between the MESP at the nucleus of Li in the Li-adsorbed nanoflake and the MESP at the free Li (− 5.72 au). In general, the values of ΔVMESP-2 are positive for the adsorption of Li on coronene and its analogues (Table 3). The positive value of ΔVMESP-2 suggests the electron density transfer from Li to nanoflakes. However, the values of ΔVMESP-2 are negative for the adsorption of Li on o-C22H12N2, m-C22H12N2, C16H12Si8, and B12H12N12. Unlike Eads-1, Eads-2 does not show a correlation with ΔVMESP-2 (see Fig. S3).

Optimized structures of Li adsorbed on (a) C24H12, (b) C23H12Si, (c) o-C22H12N2, (d) m-C22H12N2, (e) m-C22H12BN, (f) p-C22H12BN, (g) C20H12B2N2, (h) C18H12B3N3, (i) C16H12Si8, (j) C12H12Si12, (k) B12H12N12, (l) B11H12N12Al. The bond distances are given in Å. The color code is the same as in Fig. 4.

The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-3 values of Li-adsorbed coronene and its analogues are given in Table 3. The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-3 values of Li-adsorbed coronene and its analogues are in the ranges of − 5.15 (B11H12N12Al) to − 3.24 eV (B12H12N12), − 0.94 (C24H12) to 0.56 eV (B12H12N12), and 2.37 (C24H12) to 4.69 eV (B11H12N12Al), respectively. For all cases, EHOMO of the Li-adsorbed nanoflakes is higher than that of the pristine nanoflakes (see Table 1). For example, the EHOMO value of Li-adsorbed coronene is − 3.30 eV. The ELUMO of coronene and its analogues is not much affected by the presence of Li. The results here show that Eg-3 is usually lower than Eg-1. The decrease in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap for the adsorption of Li on coronene is 59.9% (see ΔEg-2 values in Table 3). A maximum decrease in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap of 60.0% was observed for the adsorption of Li on B12H12N12. However, Eg-3 is found to be higher than Eg-1 for the adsorption of Li on m-C22H12N2 (ΔEg-2 of 6.3%).

Cell voltage of the doped coronenes

The ΔEcell and Vcell of LIBs based on coronene and its analogues were calculated using eqs. (10 and 11), respectively, and their values are given in Table 3. Here the ∆Ecell and Vcell values are in the ranges of − 41.62 (C12H12Si12) to − 21.04 kcal/mol (C23H12Si) and 0.91 (C23H12Si) to 1.80 V (C12H12Si12), respectively. The more negative the ∆Ecell value, the higher the Vcell value of the nanoflakes. Therefore, the nanoflakes interacting strongly with Li+ and weakly with Li may serve as good candidates for the anode materials in LiBs. For example, the highest Vcell value of 1.80 V is observed for C12H12Si12 due to the high Eads-1 of − 52.14 kcal/mol (see Table 2) and low Eads-2 of − 10.51 kcal/mol (see Table 3). The lowest Vcell value of 0.91 V observed for C23H12Si can be attributed to a higher contribution from Eads-2 (Eads-1 of − 54.14 kcal/mol and Eads-2 of − 33.10 kcal/mol). The ∆Ecell and Vcell values of coronene are − 36.60 kcal/mol and 1.59 V, respectively. For the N-doped coronenes, the Vcell value of o-C22H12N2 (1.20 V) is lower than that of m-C22H12N2 (1.33 V). The Vcell values of Si-doped coronenes increase in the order C23H12Si < C16H12Si8 < C12H12Si12. Furthermore, the Vcell values of BN/AlN-doped coronenes increase in the order B11H12N12Al < p-C22H12BN < C18H12B3N3 < m-C22H12BN < C20H12B2N2 < B12H12N12. It can be observed that the Eads-1 data exhibit only a small variation compared to Eads-2, and therefore Eads-2 has a relatively strong influence on the variation of Vcell. The linear correlation of Eads-2 with Vcell (R = 0.805) also supports the strong influence of Eads-2 on Vcell (Fig. S4).

Circumcoronene and its analogues as anode materials in lithium-ion batteries

Structural properties of circumcoronene and its analogues

The optimized structures of circumcoronene and its analogues are given in Fig. 7, indicating all the important bond length values. As in the case of coronene and its analogues, the XY (X = C, Si, N, B, Al; Y = C, Si, N, B, Al) bond lengths of circumcoronene and its analogues are in the range of about 1.35 to 1.81 Å. We see that the CC bond lengths in circumcoronene are in the range of about 1.36 to 1.44 Å, and the six outermost CC bonds are noticeably shorter (1.36 Å) than the other ones. Here, all the CSi (> 1.72 Å) and NAl (≈1.74 Å) bond lengths are found to be significantly longer than all the CC bond lengths.

Optimized structures of (a) C54H18, (b) C53H18Si, (c) o-C52H18N2, (d) m-C52H18N2, (e) m-C52H18BN, (f) p-C52H18BN, (g) C50H18B2N2, (h) C48H18B3N3, (i) C36H18Si18, (j) C27H18Si27, (k) B27H18N27, (l) B26H18N27Al. The bond distances are given in Å. The color code is the same as in Fig. 2.

The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-1 values of circumcoronene and its analogues are given in Table 4. Our results show that the EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-1 values of circumcoronene and its analogues are in the ranges of − 8.05 (B27H18N27) to − 4.03 eV (m-C52H18N2), − 2.00 (C50H18B2N2) to 1.08 eV (B27H18N27), and 2.14 (m-C52H18N2) to 9.12 eV (B27H18N27), respectively. The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-1 values of circumcoronene are − 5.95, − 1.60, and 4.35 eV, respectively. In general, the EHOMO (ELUMO) of the doped circumcoronene is higher (lower) than that of the pristine circumcoronene. Also, the Eg-1 of the doped circumcoronene is typically lower than that of the pristine circumcoronene. The opposite trends are observed for p-C52H18BN, C48H18B3N3, C27H18Si27, B12H12N12, and B11H12N12Al. These EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-1 values reported here are consistent with previous theoretical results30.

MESP of circumcoronene and its analogues

The MESP features of circumcoronene and its analogues are given in Fig. 8. The MESP analysis indicate that as in the case of coronene, electron-rich regions (e.g., green regions) are present on circumcoronene. The replacements of C atoms of circumcoronene by Si/N/BN/AlN units lead to an increase of the electron-rich environments (e.g., blue regions) in the molecules. The MESP Vmin values of circumcoronene and its analogues are provided in Table 4. The locations of Vmin in the MESP plots of circumcoronene and its analogues are provided in Fig. S5. As in the case of coronene, the MESP Vmin points are located near the peripheral rings of circumcoronene. For the doped circumcoronenes, the MESP Vmin points are located mainly near the peripheral rings, except for C53H18Si, m-C52H18BN, p-C52H18BN, C50H18B2N2, and B26H18N27Al. We find that the MESP Vmin values of circumcoronene and its analogues are in the range of − 14.56 (C54H18) to − 33.95 kcal/mol (C27H18Si27). The MESP Vmin of the doped circumcoronene is higher than that of the pristine circumcoronene. For the N-doped circumcoronenes, the MESP Vmin value of o-C52H18N2 (− 17.19 kcal/mol) is lower than that of m-C52H18N2 (-24.03 kcal/mol). The MESP Vmin values of Si-doped circumcoronenes increase in the order C53H18Si < C36H18Si18 < C27H18Si27. Furthermore, the MESP Vmin values of BN/AlN-doped circumcoronenes increase in the order C48H18B3N3 < B27H18N27 < C50H18B2N2 < B26H18N27Al < p-C52H18BN < m-C52H18BN.

MESP mapped on 0.01 a.u. electron density isosurface of (a) C54H18, (b) C53H18Si, (c) o-C52H18N2, (d) m-C52H18N2, (e) m-C52H18BN, (f) p-C52H18BN, (g) C50H18B2N2, (h) C48H18B3N3, (i) C36H18Si18, (j) C27H18Si27, (k) B27H18N27, (l) B26H18N27Al. The Colour coding from blue to red indicates MESP values in the range -0.03 to 0.03 a.u. The Colours at the blue end of the spectrum indicate the electron-rich regions, while those toward the red indicate the electron-deficient regions.

Li+ adsorption on the doped circumcoronenes

The optimized geometries for the adsorption of Li+ on circumcoronene and its analogues are provided in Fig. 9. Our results show that as in the case of coronene, Li+ binds to the peripheral rings of circumcoronene. For the doped circumcoronenes, Li+ binds to the peripheral rings, except for C53H18Si, m-C52H18BN, p-C52H18BN, C50H18B2N2, and B26H18N27Al. Our results show that Li+ is relatively strongly adsorbed on circumcoronene and its analogues. For example, the adsorption distance of Li+ on these adsorbents is in the range of 2.21 (C36H18Si18) to 2.46 Å (C27H18Si27). This observation is further supported by the adsorption energy of Li+ on circumcoronene and its analogues (Table 5). The Eads-1 values of Li+ on circumcoronene and its analogues are in the range of − 45.36 (B27H18N27) to − 65.61 kcal/mol (C36H18Si18). The more negative the Eads-1 value, the stronger the adsorption is. The Eads-1 value of Li+ on circumcoronene is − 51.55 kcal/mol. For the N-doped circumcoronenes, the Eads-1 value of o-C52H18N2 (− 55.24 kcal/mol) is higher than that of m-C52H18N2 (− 63.51 kcal/mol). The Eads-1 values of Si-doped circumcoronenes increase in the order C53H18Si < C27H18Si27 < C36H18Si18. Furthermore, the Eads-1 values of BN/AlN-doped circumcoronenes increase in the order B27H18N27 < C48H18B3N3 ≈ B26H18N27Al < C50H18B2N2 < p-C52H18BN < m-C52H18BN. These adsorption energies are correlated with the MESP Vmin values of circumcoronene and its analogues, with a correlation coefficient of 0.726 (Fig. 10a). Note that a better correlation was observed for coronene and its analogues (see Fig. 5a).

Optimized structures of Li+ adsorbed on (a) C54H18, (b) C53H18Si, (c) o-C52H18N2, (d) m-C52H18N2, (e) m-C52H18BN, (f) p-C52H18BN, (g) C50H18B2N2, (h) C48H18B3N3, (i) C36H18Si18, (j) C27H18Si27, (k) B27H18N27, (l) B26H18N27Al. The bond distances are given in Å. The color code is the same as in Fig. 4.

The negative values of ΔVMESP-1 (Table 5) indicate the electron donation from circumcoronene and its analogues to Li+. These ΔVMESP-1 values are in the range of − 113.38 (B27H18N27) to − 155.49 kcal/mol (C27H18Si27). The ΔVMESP-1 value of circumcoronene is − 117.95 kcal/mol. The ΔVMESP-1 of the doped circumcoronenes is typically higher than that of the pristine circumcoronene. However, the ΔVMESP-1 of C48H18B3N3 and B12H12N12 is lower than that of circumcoronene. The adsorption energies of Li+ on circumcoronene and its analogues are correlated with these ΔVMESP-1 values, with a correlation coefficient of 0.898 (Fig. 10b). This behavior is similar to what we observe for coronene and its analogues (see Fig. 5b).

The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-2 values of Li+-adsorbed circumcoronene and its analogues are given in Table 5. The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-2 values of Li+-adsorbed circumcoronene and its analogues are in the ranges of − 10.28 (B26H18N27Al) to − 7.03 eV (m-C52H18N2), − 4.98 (C53H18Si) to − 3.59 eV (C27H18Si27), and 2.66 (m-C52H18N2) to 6.28 eV (B26H18N27Al), respectively. Here also, EHOMO of the Li+-adsorbed nanoflakes is lower than that of the pristine nanoflakes (see Table 4) for all cases. A similar result is obtained for ELUMO. Our results here show that Eg-2 is typically lower than Eg-1. For example, the EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-2 values of Li+-adsorbed circumcoronene are − 8.40, − 4.37, and 4.04 eV, respectively. The decrease in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap for the adsorption of Li+ on circumcoronene is 7.3% (see ΔEg-1 values in Table 5). A maximum decrease in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap of 34.1% was observed for the adsorption of Li+ on B27H18N27. However, Eg-2 is found to be higher than Eg-1 for the adsorption of Li+ on m-C52H18N2, C50H18B2N2, and C36H18Si18. A maximum increase in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap of 24.7% was observed for the adsorption of Li+ on m-C52H18N2.

Li adsorption on the doped circumcoronenes

The optimized geometries for the adsorption of Li on circumcoronene and its analogues are provided in Fig. 11. Our results show that Li binds to the peripheral rings of circumcoronene, similar to the results obtained for Li+. For the doped circumcoronenes, Li binds to the peripheral rings only of m-C52H18N2, C48H18B3N3, C36H18Si18, and C27H18Si27. The adsorption distance of Li on these adsorbents is in the range of 1.96 (B26H18N27Al) to 2.41 Å (B27H18N27). For these adsorbents, the adsorption distance of Li is generally smaller than that of Li+ (see Fig. 10). For example, the adsorption distance of Li and Li+ on circumcoronene is 2.18 and 2.29 Å, respectively. However, as in the case of coronene and its analogues, Li is weakly adsorbed on circumcoronene and its analogues when compared to Li+. This observation is supported by the adsorption energy of Li on circumcoronene and its analogues (Table 6). The Eads-2 values of Li on circumcoronene and its analogues are in the range of − 3.07 (B27H18N27) to − 47.79 kcal/mol (C53H18Si). The Eads-2 value of Li on circumcoronene is − 18.73kcal/mol. For the N-doped circumcoronenes, the Eads-2 value of o-C52H18N2 (− 22.71 kcal/mol) is lower than that of m-C52H18N2 (− 32.31 kcal/mol). The Eads-2 values of Si-doped circumcoronenes increase in the order C27H18Si27 < C36H18Si18 < C53H18Si. Furthermore, the Eads-2 values of BN/AlN-doped circumcoronenes increase in the order B27H18N27 < C48H18B3N3 < B26H18N27Al < p-C52H18BN < m-C52H18BN < C50H18B2N2. These adsorption energies are not well correlated with the MESP Vmin values of circumcoronene and its analogues (Fig. S6).

Optimized structures of Li adsorbed on (a) C54H18, (b) C53H18Si, (c) o-C52H18N2, (d) m-C52H18N2, (e) m-C52H18BN, (f) p-C52H18BN, (g) C50H18B2N2, (h) C48H18B3N3, (i) C36H18Si18, (j) C27H18Si27, (k) B27H18N27, (l) B26H18N27Al. The bond distances are given in Å. The color code is the same as in Fig. 4.

In general, the values of ΔVMESP-2 are positive for the adsorption of Li on circumcoronene and its analogues (Table 6). The positive value of ΔVMESP-2 suggests the electron density transfer from Li to nanoflakes. However, the values of ΔVMESP-2 are negative for the adsorption of Li on C27H18Si27 and B27H18N27. Here also, Eads-2 does not show a correlation with ΔVMESP-2 (see Fig. S6).

The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-3 values of Li-adsorbed circumcoronene and its analogues are given in Table 6. The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Eg-3 values of Li-adsorbed circumcoronene and its analogues are in the ranges of − 5.22 (B26H18N27Al) to − 3.21 eV (B27H18N27), − 1.69 (C36H18Si18) to 0.53 eV (B27H18N27), and 2.20 (p-C52H18BN) to 4.44 eV (B26H18N27Al), respectively. Here also, EHOMO of the Li-adsorbed nanoflakes is higher than that of the pristine nanoflakes (see Table 4) for all cases. For example, the EHOMO value of Li-adsorbed circumcoronene is − 3.63 eV. The ELUMO of circumcoronene and its analogues is not much affected by the presence of Li. The results here show that Eg-3 is usually lower than Eg-1. The decrease in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap for the adsorption of Li on circumcoronene is 49.3% (see ΔEg-2 values in Table 3). A maximum decrease in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap of 59.0% was observed for the adsorption of Li on B27H18N27. However, Eg-3 is found to be higher than Eg-1 for the adsorption of Li on m-C52H18N2 (ΔEg-2 of 23.8%).

Cell voltage of circumcoronene and its analogues

The ΔEcell and Vcell of LIBs based on circumcoronene and its analogues are given in Table 6. Here the ∆Ecell and Vcell values are in the ranges of − 42.29 (B27H18N27) to − 11.06 kcal/mol (C53H18Si) and 0.48 (C53H18Si) to 1.83 V (B27H18N27), respectively. As mentioned before, the nanoflakes interacting strongly with Li+ and weakly with Li may serve as good candidates for the anode materials in LiBs. For example, the highest Vcell value of 1.83 V is observed for B27H18N27 due to the high Eads-1 of − 45.36 kcal/mol (see Table 5) and low Eads-2 of − 3.07 kcal/mol (see Table 6). The lowest Vcell value of 0.48 V observed for C53H18Si can be attributed to a higher contribution from Eads-2 (Eads-1 of − 58.84 kcal/mol and Eads-2 of − 47.79 kcal/mol). The ∆Ecell and Vcell values of circumcoronene are − 32.82 kcal/mol and 1.42 V, respectively. For the N-doped circumcoronenes, the Vcell value of o-C52H18N2 (1.41 V) is higher than that of o-C52H18N2 (1.35 V). The Vcell values of Si-doped circumcoronenes increase in the order C53H18Si < C36H18Si18 < C27H18Si27. Furthermore, the Vcell values of BN/AlN-doped circumcoronenes increase in the order C50H18B2N2 < B26H18N27Al < m-C52H18BN < C48H18B3N3 < p-C52H18BN < B27H18N27. Here also, the linear correlation of Eads-2 with Vcell (R = 0.840) supports the strong influence of Eads-2 on Vcell (see Fig. S4).

The adsorption free energies (ΔGads = Gadsorbate/nanoflake – (Gnanoflake + Gadsorbate)) show that the adsorption of Li+ on the nanoflakes is exergonic (Table S1). The ΔGads values for the adsorption of Li+ on the nanoflakes are in the range of − 33.69 (B12H12N12) to − 56.84 kcal/mol (C36H18Si18). The adsorption of Li on the nanoflakes is generally exergonic. However, the adsorption of Li on B12H12N12 and B27H18N27 is endergonic, indicating weak interactions.

The storage capacity (C = (n x F × 103)/M, where n is the maximum number of adsorbed Li atoms and M is the molecular mass of the electrode)43 is an important factor for the performance of LIBs. To obtain the lithium storage capacity, we examined the interactions of Li atoms with, for example, C24H12. The resulting 6Li@C24H12 (Fig. S7) is found to be a true local minimum with no imaginary frequency. Therefore, the lithium storage capacity of C24H12 is 536.2 mAh/g, indicating that such nanoflakes are promising for high-capacity LIBs. For a comparison, the lithium storage capacity of graphite44 is 372 mAh/g, Sc2C MXene45 is 462 mAh/g, graphene-like C2N46 is 671.7 mAh/g, and pentagraphyne47 is 687 mAh/g.

There have been experimental studies on the use of PAHs in LIBs. For example, Park et al. obtained excellent rate capability and cycle endurance for LIBs using PAHs as anode materials9. There have also been DFT studies on the potential use of PAHs in LIBs. For example, based on the cell voltage data, Remya and Suresh suggested coronene as a good anode material for LIBs27. Based on our Vcell data, C24H12, C12H12Si12, B12H12N12, C27H18Si27, and B27H18N27 are suggested as good anode materials for the LIBs and B27H18N27 is the best among all tested nanoflakes. The Vcell of B27H18N27 is found to be 1.83 V. For a comparison, the Vcell of circumbiphenyl is 1.51 V27, sumanene is 1.68 V48, and hexa-peri-hexabenzocoronene is 1.70 V49. The insights on the adsorption mechanism from this study could help design an efficient electrode which could be useful for the further development efficient LIBs.

Conclusions

We performed DFT calculations to investigate the adsorption mechanisms of Li+ and Li on a total of twenty-four adsorbents (C24H12 and its analogues C23H12Si, o-C22H12N2, m-C22H12N2, m-C22H12BN, p-C22H12BN, C20H12B2N2, C18H12B3N3, C16H12Si8, C12H12Si12, B12H12N12, B11H12N12Al; C54H18 and its analogues C53H18Si, o-C52H18N2, m-C52H18N2, m-C52H18BN, p-C52H18BN, C50H18B2N2, C48H18B3N3, C36H18Si18, C27H18Si27, B27H18N27, B26H18N27Al). The XY (X = C, Si, N, B, Al; Y = C, Si, N, B, Al) bond lengths were in the range of about 1.35 to 1.81 Å for all adsorbents. Here all the CSi and NAl bond lengths were found to be significantly longer than all the CC bond lengths. The MESP analysis show that the replacements of C atoms of coronene and circumcoronene by Si/N/BN/AlN units lead to an increase of the electron-rich environments in the molecules.

Li+ is relatively strongly adsorbed on all adsorbents. For example, the adsorption distance of Li+ on all adsorbents is in the range of 2.15 (C16H12Si8) to 2.46 Å (C27H18Si27). This observation is further supported by the adsorption energy of Li+ on the nanoflakes. The Eads-1 values of Li+ on all adsorbents are in the range of − 42.47 (B12H12N12) to − 66.26 kcal/mol (m-C22H12BN). Our results indicate a stronger interaction between Li+ and the nanoflakes as the MESP Vmin of the nanoflakes becomes more negative. The electron donation from the nanoflakes to Li+ could be checked by assessing the changes in the MESP at the nucleus of Li+ upon adsorption. Our results show that a stronger interaction between Li+ and the nanoflakes pushes more electron density toward Li+. The HOMO–LUMO gap of Li+-adsorbed nanoflakes is typically lower than that of pristine ones.

The adsorption distance of Li on the nanoflakes is generally smaller than that of Li+. For example, the adsorption distance of Li and Li+ on circumcoronene is 2.18 and 2.29 Å, respectively. However, Li is weakly adsorbed on circumcoronene and its analogues when compared to Li+. This observation is supported by the adsorption energy of Li on the nanoflakes. The Eads-2 values of Li on all adsorbents are in the range of − 3.07 (B27H18N27) to − 47.79 kcal/mol (C53H18Si). The HOMO–LUMO gap of Li-adsorbed nanoflakes is typically lower than that of pristine ones. The nanoflakes interacting strongly with Li+ and weakly with Li may serve as good candidates for the anode materials in LiBs. Among all adsorbents, the highest Vcell value of 1.83 V is observed for B27H18N27 due to the high Eads-1 of − 45.36 kcal/mol and low Eads-2 of − 3.07 kcal/mol. The Eads-1 data of studied systems show only a small variation compared to Eads-2, and as a result, Eads-2 has a relatively strong influence on the variation of Vcell.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article and supporting information.

References

Whittingham, M. S. Lithium batteries and cathode materials. Chem. Rev. 104, 4271–4302. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020731c (2004).

Blomgren, G. E. The development and future of lithium ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, A5019. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0251701jes (2017).

Ruiz, V. et al. A review of international abuse testing standards and regulations for lithium ion batteries in electric and hybrid electric vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 1427–1452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.195 (2018).

Yuan, W. et al. The applications of carbon nanotubes and graphene in advanced rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 8932–8951. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6TA01546H (2016).

Raccichini, R., Varzi, A., Passerini, S. & Scrosati, B. The role of graphene for electrochemical energy storage. Nat. Mater. 14, 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4170 (2015).

Huang, X. et al. Graphene-based materials: Synthesis, characterization, properties, and applications. Small 7, 1876–1902. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201002009 (2011).

Li, W., Li, M., Adair, K. R., Sun, X. & Yu, Y. Carbon nanofiber-based nanostructures for lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 13882–13906. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7TA02153D (2017).

Chang, S. et al. In situ formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as an artificial hybrid layer for lithium metal anodes. Nano Lett. 22, 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c03624 (2022).

Park, J. et al. Contorted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon: Promising Li insertion organic anode. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 12589–12597. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA03633K (2018).

Wu, Z.-S., Ren, W., Xu, L., Li, F. & Cheng, H.-M. Doped graphene sheets as anode materials with superhigh rate and large capacity for lithium ion batteries. ACS Nano 5, 5463–5471. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn2006249 (2011).

Bulusheva, L. G. et al. Electrochemical properties of nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube anode in Li-ion batteries. Carbon 49, 4013–4023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2011.05.043 (2011).

Yue, H. et al. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers as anode material for high-capacity and binder-free lithium ion battery. Mater. Lett. 120, 39–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2014.01.049 (2014).

Zhang, L. et al. Boron and nitrogen co-doped porous carbon nanotubes webs as a high-performance anode material for lithium ion batteries. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 41, 14252–14260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.06.016 (2016).

Aghamohammadi, H., Hassanzadeh, N. & Eslami-Farsani, R. A review study on the recent advances in developing the heteroatom-doped graphene and porous graphene as superior anode materials for Li-ion batteries. Ceram. Int. 47, 22269–22301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.05.048 (2021).

Stępień, M., Gońka, E., Żyła, M. & Sprutta, N. Heterocyclic nanographenes and other polycyclic heteroaromatic compounds: Synthetic routes, properties, and applications. Chem. Rev. 117, 3479–3716. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00076 (2017).

Jiang, Z. et al. Synthesis, structure, and photophysical properties of BN-embedded analogue of coronene. Org. Lett. 24, 1017–1021. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.1c04161 (2022).

Zou, Y. et al. Circumcoronenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 62, e202301041. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202301041 (2023).

Galano, A. Influence of silicon defects on the adsorption of thiophene-like compounds on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: A theoretical study using thiophene + coronene as the simplest model. J. Phys. Chem. A 111, 1677–1682. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0665271 (2007).

Ghatee, M. H. & Moosavi, F. Physisorption of hydrophobic and hydrophilic 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium ionic liquids on the graphenes. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 5626–5636. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp108537q (2011).

Shakourian-Fard, M., Kamath, G. & Jamshidi, Z. Trends in physisorption of ionic liquids on boron-nitride sheets. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 26003–26016. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp506277n (2014).

Malček, M. & Cordeiro, M. N. D. S. A DFT and QTAIM study of the adsorption of organic molecules over the copper-doped coronene and circumcoronene. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostructures 95, 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2017.09.004 (2018).

Velázquez-López, L. F., Pacheco-Ortin, S. M., Mejía-Olvera, R. & Agacino-Valdés, E. DFT study of CO adsorption on nitrogen/boron doped-graphene for sensor applications. J. Mol. Model. 25, 91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-019-3973-z (2019).

Hussain, R. et al. Density functional theory study of palladium cluster adsorption on a graphene support. RSC Adv. 10, 20595–20607. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0RA01059F (2020).

dos Santos, T. C. et al. CO2 and H2 adsorption on 3D nitrogen-doped porous graphene: Experimental and theoretical studies. J. CO2 Util. 48, 101517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2021.101517 (2021).

Gal, J.-F. et al. Lithium-cation/π complexes of aromatic systems. The effect of increasing the number of fused rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 10394–10401. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja029843b (2003).

Pattarapongdilok, N. & Parasuk, V. Adsorptions of lithium ion/atom and packing of Li ions on graphene quantum dots: Application for Li-ion battery. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1177, 112779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2020.112779 (2020).

Ramya, P. K. & Suresh, C. H. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as anode materials in lithium-ion batteries: A DFT study. J. Phys. Chem. A 127, 2511–2522. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.3c00337 (2023).

Denis, P. A., Ullah, S. & Iribarne, F. Reduction chemistry of hexagonal boron nitride sheets and graphene: A comparative study on the effect of alkali atom doping on their chemical reactivity. New J. Chem. 44, 5725–5730. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0NJ00414F (2020).

Saha, B. & Bhattacharyya, P. K. Anion⋯π interaction in oxoanion-graphene complex using coronene as model system: A DFT study. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1147, 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2018.12.005 (2019).

Khudhair, A. M. & Ben Ahmed, A. Utilizing circumcoronene and BN circumcoronene for the delivery and adsorption of the anticancer drug floxuridine. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1222, 114075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2023.114075 (2023).

Geetha Sadasivan Nair, R., Narayanan Nair, A. K. & Sun, S. Adsorption of hazardous gases on Cyclo[18]carbon and its analogues. J. Mol. Liq. 389, 122923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122923 (2023).

Geetha Sadasivan Nair, R., Narayanan Nair, A. K. & Sun, S. Adsorption of Gases on Fullerene-like X12Y12 (X = Be, Mg, Ca, B, Al, Ga, C; Y = C, Si, N, P, O) Nanocages. Energy Fuels 37, 14053–14063. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c01973 (2023).

Frisch, M. J. et al. (Gaussian, Inc. 2016).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x (2008).

Suresh, C. H., Remya, G. S. & Anjalikrishna, P. K. Molecular electrostatic potential analysis: A powerful tool to interpret and predict chemical reactivity. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1601. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1601 (2022).

Remya, G. S. & Suresh, C. H. Assessment of the electron donor properties of substituted phenanthroline ligands in molybdenum carbonyl complexes using molecular electrostatic potentials. New J. Chem. 42, 3602–3608. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7NJ04592A (2018).

Remya, G. S. & Suresh, C. H. Hydrogen elimination reactivity of ruthenium pincer hydride complexes: A DFT study. New J. Chem. 43, 14634–14642. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9NJ03100F (2019).

Boys, S. F. & Bernardi, F. The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors. Mol. Phys. 19, 553–566 (1970).

Yu, Y.-X. Prediction of mobility, enhanced storage capacity, and volume change during sodiation on interlayer-expanded functionalized Ti3C2 MXene anode materials for sodium-ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 5288–5296. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b10366 (2016).

Mittendorfer, F. & Hafner, J. Density-functional study of the adsorption of benzene on the (111), (100) and (110) surfaces of nickel. Surf. Sci. 472, 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6028(00)00929-8 (2001).

Weinelt, M. et al. The electronic structure of ethylene on Ni(110): An experimental and theoretical study. Surf. Sci. 271, 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-6028(92)90915-S (1992).

Sayyed, F. B. & Suresh, C. H. Quantitative assessment of substituent effects on cation−π interactions using molecular electrostatic potential topography. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 9300–9307. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp205064y (2011).

Shakerzadeh, E. & Azizinia, L. Can C24N24 cavernous nitride fullerene be a potential anode material for Li-, Na-, K-, Mg-, Ca-ion batteries?. Chem. Phys. Lett. 764, 138241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2020.138241 (2021).

Dahn, J. R., Zheng, T., Liu, Y. & Xue, J. S. Mechanisms for lithium insertion in carbonaceous materials. Science 270, 590–593 (1995).

Lv, X. et al. Sc2C as a promising anode material with high mobility and capacity: A first-principles study. ChemPhysChem 18, 1627–1634. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.201700181 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. Graphene-like carbon-nitrogen materials as anode materials for Li-ion and mg-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 487, 1026–1032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.05.155 (2019).

Deb, J., Ahuja, R. & Sarkar, U. Two-dimensional pentagraphyne as a high-performance anode material for Li/Na-ion rechargeable batteries. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 10572–10582. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.2c01909 (2022).

Gharibzadeh, F., Vessally, E., Edjlali, L., Eshaghi, M. & Mohammadi, R. A DFT study on sumanene, corannulene, and nanosheet as the anodes in Li−ion batteries. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 39, 51–62. https://doi.org/10.30492/ijcce.2020.106867.3568 (2020).

Wu, X., Zhang, Z. & Soleymanabadi, H. Substituent effect on the cell voltage of nanographene based Li-ion batteries: A DFT study. Solid State Commun. 306, 113770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssc.2019.113770 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This publication is based upon work supported by the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) Office of Sponsored Research (OSR) under Award No. ORFS-2022-CRG11-5028. R. G. S. N. and A. K. N. N. would like to thank KAUST for providing computational resources of the Shaheen II supercomputer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R. G. S. N.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, visualization, writing original draft; A. K. N. N.: conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing; S.S.: resources, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http≥//creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geetha Sadasivan Nair, R., Narayanan Nair, A. & Sun, S. Density functional theory study of doped coronene and circumcoronene as anode materials in lithium-ion batteries. Sci Rep 14, 15220 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66099-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66099-6

This article is cited by

-

Edge carboxyl group functionalized RhN4-coronene as a catalyst for oxygen reduction and hydrogen evolution reactions: a DFT study

Theoretical Chemistry Accounts (2025)