Abstract

A field investigation took place at Central Research Farm of Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya, West Bengal, India during winter seasons of 2020–21 and 2021–22 with the aim to evaluate system productivity, economics, energetics and carbon footprint (CF) of oat + grasspea intercropping systems under different integrated nutrient managements (INM). The experiment was executed in split-plot design with 4 cropping systems in main plots and 4 levels of nutrient management in sub plots. The 3:3 intercropping system of oat + grasspea ensured highest system productivity, whereas sole grasspea stood best in terms of economics, energetics and environment safety by lowering CF. Notably, INM involving 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost registered significantly higher system productivity in case of 3:3 oat + grasspea intercropping system (CS4N3) (18.77 q ha−1). Further, this intercropping system yielded high economic profitability (net return: US$ 430.4 ha−1, benefit–cost ratio: 1.71) as well as energy indices (energy output: 71179.1 MJ ha-1, net energy gain: 60352.0 MJ ha−1, energy ratio: 6.57 and energy profitability: 5.57). CF was also found relatively low under CS4N3 (Yield scaled CF: 62.2 kg CO2-e q−1). Furthermore, high carbon efficiency (7.92) and carbon sustainability index (6.92) were also exhibited by CS4N3 as it produced maximum carbon output (1801.2 kg ha−1). In conclusion, the 3:3 oat + grasspea intercropping system using INM can be viable option to ensure economic and energy viability and minimize greenhouse gas emissions without compromising system productivity. Particularly, this intercropping system combined with 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost as INM option can be recommended for the cereal and legume growers of India, specifically under intensive cropping scenario.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the need of fodder production for achieving high livestock productivity, it is neglected over the years as agricultural lands are devoted to food grain production leading towards demand–supply disparity1. To address this disparity as well as to ensure food security, agricultual crops should be selected in such way, which can serve dual purpose i.e. food and fodder. Among the cereals, oat (Avena sativa L.) is now gaining popularity as dual purpose crop2. It is rich in carbohydrate, proteins and dietary fiber. However, appropriate management practices are required for adequate production of this cereal crop. Deterioration of soil health, particularly, soil fertility, is a prevalent phenomenon in today’s intensive agriculture and is primarily encountered with continuous cultivation of cereal crops3. This can be addressed by proper nutrient management as well as other suitable agronomic practices.

Continuous use of inorganic fertilizer and pesticides is not only creating environmental issues4, but also showing set back in crop production5,6. It has been reported that various forms of energy and other inputs, use of machines, fuel consumption, excessive and unscientific applications of chemical pesticides and fertilizers contribute around 24% of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the world7,8. All these can be addressed by substitution of chemical fertilizers with organic manures. However, considering the present need of food as well as limited availability of raw materials for preparation of organic manures, it is better to combine both organic and inorganic nutrient sources together as integrated nutrient management (INM) rather than complete reliance on any one of these. Applying too much fertilizer may not always result in higher crop yields because some of it may stay in the soil and not be used up by the crop, or it may be lost through leaching or volatilization and end up being dangerous and polluting the environment9. In order to maximize nutrient use efficiency, it is imperative that INM approaches minimize nutrient losses through leaching, runoff, volatilization, emissions, and immobilization10. In order to support agricultural productivity and slow down land degradation, INM also seeks to improve the physical, chemical, biological, and hydrological qualities of soil9. Suitable INM practice can reduce the negative impacts of fertilizers on environment; address the shortage of bulk raw material for organic manures as well as utilize the benefits of each source of nutrients for crop production11. Several research works demonstrate that INM has great benefits and can influence crop development and sustainability by reducing the harmful impacts of over-use of chemical fertilizers on soil and the surrounding environment12. Crop productivity and growth under INM are frequently on par with or even higher than those under conventional systems. Due to some of the additional benefits of organic manure over N, P, and K supply, such as increased microbial activity, better supply of macro- and micronutrients like S, Zn, C, and B, plant growth-promoting substances, etc., and lower nutrient losses from the soil, INM generally performs similarly to or better than conventional chemical-based farming. Crop yields under INM are increased by 1.3–66.5% across a range of agricultural systems when compared to traditional nutrient management13. Notably, under INM, yield benefits are already established for field crops like rice, wheat, and soybeans as well as for vegetable crops like okra, tomato, onion etc.14 and therefore, it is expected that INM can also exhibit positive influence on cereal + legume intercropping system.

Additionally, cereal + legume intercropping system itself plays a key role in reviving soil health and fertility through biological nitrogen fixation as well as improving soil biological properties by legumes, resulting in enhancement of higher system productivity15. Intercropping serves as a promising measure to suppress weeds; conserve soil moisture and provide additional income. Grasspea (Lathyrus sativus L.) is an important winter legume crop which can be grown under poor soil and management conditions alone or accompanied with other11. It is hypothesized that intercropping of oat with grasspea can be useful not only in uplifting the dual purpose oat productivity but also overall system productivity. Further, use of suitable INM practice can improve soil fertility and productivity of both the crops as well as minimize the carbon footprints.

In present-day’s agriculture, optimization of energy input by its better utilization is one of the prime factors for realizing high productivity, profitability and sustainability of agricultural system16. Energy efficiency in agriculture reduces environmental risks and preserves a variety of priceless resources. Consequently, farmers and policymakers may find that the evaluation of a crop’s energetics is a crucial consideration when making farming decisions17. According to earlier studies, energy dynamics assessment is important for agriculture since it is a crucial input that determines crop productivity18,19. Such analyses of energy have recently been conducted for numerous cereals, vegetables, pulses, sugar, and fiber crops20,21. It has been further reported that various anthropogenic activities specially, agriculture are responsible for emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs) which hamper the environment’s safety and affect the living organisms22. Complete reliance on excessive uses of inorganic fertilizer results in loss of nutrients, and consequently, long term persistence in the environment as well as emission of GHGs23. Additionally, emission of N2O due to farming activities is aggravated by enhanced carbon emission24. Therefore, being a global warming indicator, proper quantification and assessment of carbon footprint (CF) can help the crop to cope up with climate change and mitigate environmental issues25. Energy-intensive farming methods are known to increase CF, and appropriate management techniques are required to improve energy use efficiency and lower CF in agriculture. Thus, the following experiment was planned with the aim to evaluate system productivity, economics, energetics and carbon footprint in oat + grasspea intercropping system under INM options.

Materials and methods

Experimental site and time of experiment

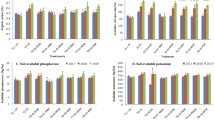

The field experiment was conducted at the Central Research Farm of Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Gayeshpur, Nadia, West Bengal, India (23°N latitude, 89°E longitude at an elevation of 9.75 m from mean sea level) during winter seasons of 2020–21 and 2021–22. The soil of experimental site was sandy loam in texture belonging to the order of Inceptisols and is having neutral in pH (6.75) with organic carbon of 0.51%, low in available nitrogen (N) (196.5 kg ha−1), medium in phosphorus (P) (47.2 kg ha−1) and potassium (K) (198.4 kg ha−1). Meterological condition during the period of investigation has been shown in Fig. 1.

Treatment details

The experiment was conducted in split-plot design with 4 cropping systems in main-plots and 4 nutrient management options in sub-plots, replicated thrice. Details of main- and sub-plots treatments have been given below:

Main-plots: Cropping systems (CS)

CS1: Sole oat.

CS2: Sole grasspea.

CS3: 3:2 intercropping system of oat + grasspea.

CS4: 3:3 intercropping system of oat + grasspea.

Sub-plots: Nutrient managements (N)

N1: 100% recommended dose of fertilizers (RDF).

N2: 75% N through urea + 25% N through farm yard manure (FYM).

N3: 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost.

N4: 75% N through urea + 25% N through mustard oilcake.

The nutrient composition of different organic manures has been analyzed through the standard methods26 and shown in Table 1. Further, the quantities of organic manures and inorganic fertilizers applied in different treatments have been shown in Table 2.

Experimental details

Oat (var. OS-6) and grasspea (var. Bio L 212) were sown continuously at 25 cm and 20 cm row-row distances, respectively, during last week of November. Oat was sown using seed rates of 100 kg ha−1, 70 kg ha−1 and 57 kg ha−1 for CS1, CS3 and CS4, respectively, while grasspea was sown using seed rates of 50 kg ha−1, 15 kg ha−1 and 20 kg ha−1 for CS2, CS3 and CS4, respectively. Plot size was 4 m × 3 m. RDF (N: P2O5: K2O) for sole oat and grasspea were 80:60:40 kg ha−1 and 20:40:30 kg ha−1, respectively. In both the intercropping systems, RDF for oat i.e. 80:60:40 kg N: P2O5: K2O ha-1 was applied. In sole oat and intercropping systems, entire P2O5 and K2O through S.S.P and M.O.P. were applied as basal during last land preparation while, N was applied in 3 splits (50% at basal in form of urea (25% N) and FYM/vermicompost/mustard oilcake (25% N), 25% N as urea at 25 days after sowing (DAS) and 25% N as urea at 1 day after cutting of oat made at 60 DAS). In sole grasspea, all the nutrients were applied at basal through these fertilizers and organic manures. Other agronomic practices were done as per the standard recommendations.

Observations

Observations included system productivity, production economics, energetics as well as carbon footprint. For achieving system productivity, crop equivalent yield was calculated through the following formula where grasspea seed yield and stover yield as well as oat green fodder yield and stover yield were converted into oat grain equivalent yield:

where, Yi = Yield of ith crop, Pi = Price of ith crop, Pj = Price of jth crop.

System productivity was calculated through following formula:

where, Y1 = Oat grain yield, Y2 = Oat grain equivalent yield of its green fodder, Y3 = Oat grain equivalent yield of its dry stover, Y4 = Oat grain equivalent yield of grasspea seed, Y5 = Oat grain equivalent yield of grasspea dry stover.

Economic analysis

Production economics on a hectare basis included cost of cultivation (US$), gross return (US$), net return (US$) and benefit–cost ratio (B:C). Production economics was chalked out as following:

Energy budgeting and energy indices

Energetics of oat-grasspea cultivation was described through energy budgeting and estimation of energy indices. Energy values of each and every inputs (i.e. energy input) were computed by multiplying their required unit (time/quantity/amount) with respective energy equivalent values (Table A1 in supplementary file)27,28,29,30. Energy output was also chalked out by multplying quantitites of produce (oat and grasspea; presented in Table A2 of supplementary file) with their respective energy equivalent values (Table A1 in supplementary file). In case of energy input, calulation of energy was done for common inputs as well as for the inputs which are variable as per the treatments and presented in Table A3 and Table A4, respectively, in supplementary file. Machine energy was estimated using the follwing formula29:

Where, ME, W, L, T and E indicated machine energy (MJ ha−1), weight of machine (kg), life span of machine (hours), time of operation (hours) and energy equivalent (MJ ha−1), respectively.

Energy input as per their energy sources was divided into direct energy and indirect energy as well as renewable and non-renewable energy forms31,32 and shown in Fig. 2. Percent sharing of energy inputs from different energy sources were finally estimated.

Various energy indices were calculated using the following formulas33:

where, NEG, ER, SE, EP, EI, NER, HEP, EPt indicated net energy gain (MJ ha−1), energy ratio, specific energy (MJ kg−1), energy productivity (kg MJ−1), energy intensiveness (MJ US$−1), nutrient energy ratio, human energy profitability and energy profitability, respectively. Eo, Ei, Yt, TCP, En, El represented energy output, energy input, biological yield (kg ha-1), total cost of production (US$), energy derived from nutrient sources (MJ ha-1) and energy derived from human labour (MJ ha−1), respectively.

Carbon footprint

Carbon footprint (CF) on spatial as well as yield scale was evaluated to observe the impacts of nutrient management in oat-garsspea cropping systems on the environment. Spatial CF indicated the total green house gas emission (CO2 and N2O) during period of crop growth and expressed in terms of CO2 equivalents34. CH4 was not taken into account in the CF calculation since, in well-drained soil conditions, its emission may have been minimal. CO2 and N2O were converted into CO2 equivalent levels over a 100-year period using global warming potential equivalent factors of 1 and 265 on a volume basis, respectively35. All crop management operations (land preparation, sowing, fertilizer and manure applications, irrigation, weeding, cutting of fodder, harvesting, post-harvest operations, etc.) and inputs (seeds, water, fertilizer, manure, fuel, electricity, etc.) were taken into consideration separately and multiplied their amount or quantity with the corresponding CO2 emission factors shown in Table A5 in the supplementary file in order to obtain CO2 emissions36,37,38,39,40.

The amount of N2O emitted due to application of N fertilizer and manure was calculated by the following equation41:

where N2O emissions = N2O emissions from inorganic N fertilizer as well as manures (kg ha-1), EF1 = Emission factor 0.01 for N2O emissions due to addition of N inputs41, kg N2O-N-kg N-1 input.

Global warming potential (GWP) was chalked out from the emissions of N2O and CO2 using the following equation40:

Spatial carbon footprint (CFs) was estimated using the following formula42:

where, n = number of components that contributed in GWP. Carbon footprint was calculated by summing up the GWP of all components. The index was shown by ‘i’, which considered values starting with the value on the right-hand side of the equation and ending with the value above the summation sign (n).

Yield-scaled carbon footprint (CFy) was calculated by using the following equation40:

CFs and CFy were expressed in kg CO2-eq ha−1 and kg CO2-eq q system productivity−1, respectively.

Carbon input, carbon output, carbon efficiency and carbon sustainability index

Carbon input was calculated using the following formula43:

Total carbon emission was calculated by summing up the carbon emissions from all the inputs.

Carbon output (kg CO2-eq ha−1) was estimated using the total C present in biomass which was chalked out by multiplying the yield with 40% C, as it was assumed that biomass contains 40% C43.

Carbon efficiency and carbon sustainability index were estimated using the Eqs. 17 and 18, as suggested by Lal37 and Chaudhary et al.43, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance method (ANOVA) was used for statistical analysis of system productivity, energetics and carbon footprint. Treatement means were compared as per Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) at 5% significance level using the STAR software version 2.0.144. Further, regression analysis was done between different variables using SPSS statistical software (version 25.0).

Declaration

Experimental research and field studies on plants, including the collection of plant material, were conducted following the institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Results

System productivity

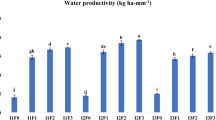

System productivity significantly varied (p ≤ 0.05) among cropping systems and found maximum in case of 3:3 intercropping system of oat + grasspea (CS4) (16.57 q ha−1), closely followed by sole grasspea (CS2) (15.81 q ha−1) (Table 3). When compared to sole oat, both intercropping systems demonstrated higher productivity (CS1). Table 3 showed that the choices for nutrient management also had a substantial (p ≤ 0.05) impact on system productivity. The best productivity, 17.52 q ha−1, was achieved by applying 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost (N3). This was followed by 75% N through urea + 25% N through mustard oilcake (N4), 75% N through urea + 25% N through FYM (N2), and 100% RDF (N1). It was further noticed that interaction of cropping system and nutrient management significantly influenced (p ≤ 0.05), even resulting in greater productivity than their individual effects (Fig. 3). Particularly, the 3:3 intercropping system of oat + grasspea grown under application of 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost (CS4N3) recorded maximum system productivity (18.77 q ha−1), closely followed by application of 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost to sole grasspea (CS2N3) (18.25 q ha−1). Among the three oat based cropping systems, the lowest system productivity was noted from 3:2 intercropping system of oat + grasspea grown under application of 100% RDF (CS3N1) (14.33 q ha−1).

Economics

Economic analysis of oat-grasspea cropping system indicated that irrespective of the cropping systems, economic profit was more when 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost (N3) was applied. Specifically, gross returns were found maximum under this in all the cropping systems except sole oat. Likewise, net return (NR) and B:C were also influenced by both cropping systems and nutrient management option. The highest NR (US$ 776.7 ha-1) and B:C (2.96) were generated by sole grasspea grown under 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost (CS2N3) (Table 4). Among the two intercropping systems, NR was higher in 3:3 intercropping system of oat and grasspea (CS4) with full RDF through inorganic source (N1) (US$ 431.0 ha−1), marginally followed by 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost (N3) (US$ 430.4 ha−1). The 3:3 intercropping system of oat and grasspea (CS4) with full RDF through inorganic source (N1) also generated higher B:C (2.09).

Energetics

Energy involved in various cultivation practices was grouped into direct (direct release of energy) and indirect (release of energy after conversion/modification) energy sources as well as renewable (energy can be recycled) and non-renewable (energy is lost after its use) energy sources (Fig. 2). The percentage of energy used by different inputs showed that, with the exception of sole grasspea, indirect energy, particularly from non-renewable sources, was used in other cropping systems. (Fig. 4). Sole grasspea was cultivated utilizing mostly the direct non-renewable energy.

Energy involved in various common and treatment-wise inputs and operations as well as energy obtained from various plant produce/parts in oat-grasspea systems were shown in Table 5. Energy involved in common inputs and operations was 3629.5 MJ ha−1, while treatment wise energy ranged from 2588.9 MJ ha−1 to 9383.8 MJ ha-1. Sole grasspea, especially, grown under 75% N through urea + 25% N through mustard oilcake (CS2N4) utilized lowest energy (6218.4 MJ ha−1), while sole oat grown under 75% N through urea + 25% N through FYM (CS1N2) required maximum energy (13013.3 MJ ha−1). Two intercropping systems especially, that of 3:3 ratio required relatively less energy over sole oat. Among intercropping systems, oat + grasspea (3:3) grown under 75% N through urea + 25% N through mustard oilcake (CS4N4) used least energy (10054.8 MJ ha−1), followed by oat + grasspea (3:2) grown under the same treatment (N4) (10224.0 MJ ha−1).

Sources of energy output were oat grain and grasspea seed as well as their stover. In contrast to intercropping systems, the crops’ individual sole populations produced a higher amount of energy (Table 5). Higher energy was produced by oat than by grasspea. The maximum amount of energy was produced by sole oat crop grown with 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost (CS1N3) (73,395.8 MJ ha−1), followed by oat + grasspea (3:3) grown under 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost (CS4N3) (71,179.1 MJ ha−1). Lowest energy was obtained from sole grasspea grown under 100% RDF (CS2N1) (33,911.5 MJ ha−1).

Various energy indices of oat-grasspea cropping systems were presented in Table 6. Maximum NEG was observed from CS1N3 combination (62,022.9 MJ ha−1), followed by CS1N4 (60,376.4 MJ ha−1) and CS4N3 (60,352.0 MJ ha−1), while lowest NEG was shown by CS2N1 (27,454.9 MJ ha−1). Further, CS2N3 showed highest ER (6.93) and it was least in case of CS3N2 (4.80). The highest specific energy (SE) was found in CS3N2 (3.36 MJ kg−1), followed by CS1N2 (3.25 MJ kg−1) and CS4N2 (3.24 MJ kg−1). The lowest SE was found in both CS2N3 and CS2N4 (1.92 MJ kg−1). Nevertheless, the combinations CS2N3 and CS2N4 guaranteed the highest EP (0.52 kg MJ−1), while the combination CS3N2 recorded the lowest EP (0.30 kg MJ−1). Energy intensiveness (EI) varied between combinations; CS1N1 had the highest EI (28.6 MJ US$−1) and CS2N4 had the lowest (16.0 MJ US$−1). Nevertheless, NER was lowest from both CS3N2 and CS4N2 (8.4) and greatest from CS2N4 (26.6), followed by CS2N3 (24.6). Maximum HEP was shown by CS4N3 (56.9). CS2N1, on the other hand, recorded lowest HEP (31.0). Considering the energy profitability (EPt), CS2N3 stood best (5.93), followed by CS2N4 (5.92), while it was found lowest from CS3N2 combination (3.80).

Carbon footprint

In this experiment, the emission of GHGs due to the influence of various factors was studied. Variations in CF (kg CO2-e ha−1) existed under different cropping system and nutrient management options. According to different sources, CFs were listed in Table 7. With the exception of sole grasspea (CS2), the nitrogenous fertilizer (range: 74.4–396.8 kg CO2-e ha−1; greatest under CS1N1, CS3N1, and CS4N1) accounted for the most CF in the other treatment combinations. This was followed by farm-derived N2O (range: 83.3–333.1 kg CO2-e ha−1; lowest under CS2, regardless of nutrient management options). Among the other inputs, the application of inorganic NPK fertilizer produced the highest total CF. Bullock labour produced the least amount of CF (2.3 kg CO2-e ha−1). In terms of total carbon, it was found that 100% RDF (N1) produced the most, independent of cropping system, and that the order of CF under different nutrient levels was N1 > N2 > N3 > N4 (Fig. 5). Among cropping system and nutrient management levels, lowest CF was noted from CS2N4 (609.0 kg CO2-e ha−1) which was 52.78% less than the CF generated under CS1N1 combination, followed by CS2N3. Among oat-grasspea intercropping systems, lowest CF (1157.6 kg CO2-e ha−1) was recorded from CS4N4, closely followed by CS4N3 (1166.5 kg CO2-e ha−1), CS3N4 (1169.1 kg CO2-e ha−1) and CS3N3 (1178.0 kg CO2-e ha−1). Irrespective of cropping systems, N4 showed 3.81–7.69% less CFs than 100% RDF, with N3 coming in second (3.35–6.98% less CFs). Two intercropping systems showed lower CF than sole oat (CS1), and CS4 showed comparatively lower CF than CS3.

Yield-scaled CF (CFy) was found lowest in CS2 (range: 33.5–41.6 kg CO2-e q−1), followed by CS4 (range: 62.2–82.8 kg CO2-e q−1) and CS3 (range: 68.7–88.3 kg CO2-e q−1). It was maximum in CS1 (range: 75.5–89.9 kg CO2-e q−1), irrespective of nutrient management levels. Lowest CFy (33.5 kg CO2-e q−1) was recorded by CS2N3, while CS1N1 generated highest CFy (89.9 kg CO2-e q−1). The sequence of nutrient management options in generating CFy was N1 > N2 > N4 > N3.

Analysis on C input and output explored that irrespective of nutrient management, CS2 required lowest C input (range: 143.4–150.0 kg ha−1), while CS1 required maximum one (range: 234.6–260.9 kg ha−1) (Table 8). Among two intercropping, C input requirement in CS4 (range: 224.9–251.2 kg ha−1) was comparatively lesser than CS3 (range: 228.0–254.3 kg ha−1) (Fig. 6). However, CS2 generated lowest C output (range: 1011.6–1337.6 kg ha−1), while relatively higher C output was produced by CS1 (range: 1558.8–1722.4 kg ha−1). Among the nutrient management options, maximum C output was generated by N3, followed by N4, N2 and N1. CS4N3 recorded maximum C output (1801.2 kg ha−1), while lowest C output was resulted from CS2N1 (1011.6 kg ha−1). C efficiency (CE) and C sustainability index (CSI) indicated that CS2 stood best (CE: 6.75–9.28, CSI: 5.75–8.28), followed by CS1 (CE: 5.97–7.27, CSI: 4.97–6.27), CS4 (CE: 5.70–7.92, CSI: 4.70–6.92) and CS3 (CE: 5.66–7.03, CSI: 4.66–6.03). The sequence of nutrient management in ensuring CE and CSI was N3 > N4 > N2 > N1. The highest CE (9.28) and CSI (8.28) were obtained from CS2N3, while CS3N1 showed lowest CE (5.66) and CSI (4.66).

Regression analysis

Regressional relationships revealed that medium to very strong relationships existed among the different variables (Fig. 7). According to coefficient of determination (R2), medium correlation existed between system productivity and specific energy (R2 = 0.4106), system productivity and energy productivity (R2 = 0.3995), system productivity and carbon efficiency (R2 = 0.5639) as well as system productivity and yield scaled CF (R2 = 0.3195). Moderately strong correlation occurred among energy input and energy output (R2 = 0.7079). Regression analysis further revealed that strong correlation among energy input and carbon input (R2 = 0.8696) as well as energy input and CF (R2 = 0.8844). Highly strong correlation existed among energy output and carbon output (R2 = 0.9430).

Relationships between system productivity and specific energy (a), energy productivity (b), carbon efficiency (d), yield scaled carbon footprint (h); Relationships between energy input and output (c), energy input and carbon input (e), energy output and carbon output (f), energy input and carbon footprint (g); units of these parameters are shown in text.

For screening of ideal cropping system under suitable INM option, a heat map based on system productivity, economics, energetics and emission related parameters was made to demonstrate 19 parameters of 16 cropping system-INM combinations in a single grid, where each parameter was transformed into 0–100 scale for easy comparison (Fig. 8). It was observed that system productivity was found highest under CS4N3 whereas B:C, energy ratio, energy productivity, energy profitability, carbon efficiency and carbon sustainability index were found highest under CS2N3. On the other hand, cost of cultivation, energy output and net energy gain were highest under CS1N3, while CS1N2 and CS1N1 recorded highest energy input and intensiveness, respectively. CS2N4 performed better in terms of energy productivity and energy derived from nutrients, while CS3N2 and CS4N3 recorded highest specific energy and energy from human labour, respectively. Further, CS2N4 showed least carbon footprint and carbon input, while CS2N3 and CS2N1 recorded least yield scaled carbon footprint and carbon output, respectively. Carbon footprints and carbon input were highest from CS1N1, while CS4N3 recorded maximum carbon output.

Comparison between different cropping systems under nutrient management levels based on productivity, economics, energetics and carbon footprint (Indicators transformed to 0–100 scale).[Here, SP, COC, B:C, IE, OE, NEG, ER, SE, EP, EI, NER, HEP, EPt, CF, YSCF, CI, CO, CE and CSI indicate system productivity, cost of cultivation, benefit–cost ratio, input energy, output energy, net energy gain, energy ratio, specific energy, energy productivity, energy intensiveness, nutrient energy ratio, human energy profitability, energy profitability, carbon footprint, yield-scaled carbon footprint, carbon input, carbon output, carbon efficiency, carbon sustainability index, respectively].

Discussions

In this study, oat based intercropping systems were only compared with sole oat due to the fact that farmers are reluctant to grow sole grasspea as it contains neurotoxin BOAA which causes ‘lathyrism’. On the other hand, oat apart from providing grain yield can also meet green forage requirement of livestock to increase their productivity. As observed in case of system productivity, 3:3 intercropping systems of oat + grasspea (CS4) performed best perhaps due to higher biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) potential of grasspea which influenced growth of both the crops as well as high market price of the legume produce. The present result was congruous to the observations of Dhakal45 and Choudhary46 in maize + cowpea intercropping, Mohan et al.47 in maize + french bean intercropping and Pandita et al.48 in maize + field bean intercropping. Further, application of 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost (N3) resulted in attaining highest system productivity. It was probably due to the beneficial impact of vermicompost on both crops’ yields by supplying adequate nutrients, which ultimately reflected on system productivity. Besides, vermicompost as a regulator of several endogenous hormonal activities inside the plant was possibly responsible for pollen germination and pollen tube growth and thereby, exerted a direct effect on yield enhancement of both the crops49. This result was corroborated with the findings of Yadav et al.50 in maize + mung bean intercropping system.

Production economics is the most important factor for adopting the cultivation practice of a particular crop or intercropping system in a specific zone. In the present study, higher gross return was the reflection of crop yield which was found maximum in N3, possibly due to vermicompost's benefits in INM. However, N3 treatment had higher cultivation costs due to high market prices and bulk requirement of vermicompost for 25% inorganic N. 100% RDF (N1) had the lowest cost of cultivation due to less inorganic fertilizer requirements. It was further noticed that sole grasspea using 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost (CS2N3) exhibited highest B:C (2.96) owing to higher market value of grasspea produce and less cost of cultivation as there was low requirements of nutrient in the form of organic and inorganic sources and most of the nitrogen requirement was met by BNF through this legume crop. However, in other cropping systems, B:C was found more in cropping systems having low cultivation costs when full RDF through inorganic source (N1) was employed, which is in line with other studies by Sarkar et al.51 and Sutaria et al.52. Beneficial effect of BNF from legume on yield of both crops and thereby, production economics was also noticed in sorghum-cowpea intercropping system53.

Various sources of energy required for cultivation of oat and grasspea alone or in combination under nutrient management options explored that indirect as well as non-renewable energy sources were mostly utilized. The findings of the study suggest that oat-based cropping systems required more fertilizers and organic manures in their nutrient management programs. Grasspea, in contrast to oats, is a low feeder of external nutrients, meaning that it needed less fertilizer and/or organic manures and utilized mostly the direct non-renewable sources of energy such as fuel, electricity specifically for land preparation, water management etc. Ray et al.54 also similarly observed from their study that heavy feeder crops such as rice, potato etc. required most of the energy from nutrient source. They also noted that inclusion of legume crop lentil in cropping system resulted in less consumption of indirect energy and more consumption of direct energy sources like diesel.

It was also noted that sole oat grown under 75% N through urea + 25% N through FYM (CS1N2) utilized highest energy (13,013.3 MJ ha−1) due to increased nutrient requirements, seeds, water, and intercultural operations. Besides, FYM, due to its low N content, contributed to high energy input through its uses of bulk quantities. Conversely, sole grasspea grown under 75% N through urea + 25% N through mustard oilcake (CS2N4) required lowest energy (6218.4 MJ ha−1) for its cultivation due to its less requirement of fertilizers especially, nitrogen. Further, mustard oilcake, being concentrated, requires less energy than other nutrients, possibly due to its low consumption by the crops especially grasspea, indicating that nutrients are crucial for crop cultivation. This study thus confirmed that sources of nutrients altogether make a key contribution to total energy requirement of a crop cultivation. Previously, Moerschner55 in a study, stated that around 55% of energy was derived from N-fertilizers. Similar observations were also noticed by Kelm et al.56, Ozkan et al.57 and Rathke and Diepenbrock58. The 3:3 oat + grasspea intercropping system utilized relatively less energy over sole oat probably due to less requirement of seeds, weeding and other intercultural operations. Ghosh et al.59 previously verified that cereal crops use more energy than legume crops. The seeds of oat and grasspea, along with their stover, produced energy. Because there were more plants growing when crops were grown alone, the maximum energy output was achieved in comparison to the populations of the individual plants in intercropping systems. Oat showed higher energy output than grasspea out of the two crops. It was possibly due to comparatively higher production of oat over grasspea. Further, N3 helped to generate higher energy output as compared to other treatments probably due to positive influence of INM using vermicompost on crop reflecting directly on energy output. Among the two intercropping systems, oat + grasspea at 3:3 ratios generated higher energy output. It was speculated that higher plant population of grasspea in this system leading to high biological nitrogen fixation, as well as higher spacing leading to less shading effect of oat on grasspea etc. as compared to 3:2 oat + grasspea intercropping system possibly helped both the crops to grow well; generate high yield and thereby, energy output. Sole grasspea generated less energy output due to its low yield potential as common in case of legumes.

According to a number of energy indices, sole oat treated with 75% N through urea + 25% N with vermicompost had a significantly higher net energy gain than sole grasspea, which had the greatest energy ratio. Vermicompost’s positive effects on crop productivity and soil health led to a comparatively high energy output over energy input, which produced a high energy ratio and net energy gain. The 3:3 intercropping system of oat + grasspea also achieved high net energy gain possibly due to combined beneficial effects of biological nitrogen fixation by grasspea as well as the INM involving vermicompost60. Further, INM option incorporating mustard oilcake (N4) in sole grasspea generated high energy productivity, nutrient energy ratio etc. Specific energy, energy profitability as well as human energy profitability and energy intensiveness were found high under 75% N through urea + 25% N through FYM, 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost and 100% RDF, respectively. According to many researchers, agronomic practices with high variations between energy output and input result in high net energy gain and energy ratio and consequently, confirm their role in bio-energy management for its environmental and economic sustainability18 61. Earlier, similar finding was found in soybean62.

Assessment of CF, further, revealed that the contribution to CF was more from inorganic NPK fertilizers especially, with the use of high nitrogenous fertilizer which possibly caused increments in biomass production, improvements in soil biological activity leading towards high CF through emitting high CO263. Additionally, external use of N fertilizer might be the significant contributor of N2O which was the potential source of GHGs emission64. Bullock labours showed less CF as they were used for a less period of time to plough the field. Overall, 100% use of inorganic fertilizer generated maximum CF over others. Similar observation was noted by DeForest et al.65. This suggested for a reduction of inorganic fertilizer use and encouraged the use of organic nutrient source or INM. Among the INM, least CF was recorded by INM having mustard oilcake (N4), followed by INM having vermicompost (N3). Requirement of less quantity of this concentrated manure and 25% reduction of inorganic N fertilizer might be the reason behind such outcome. Sole grasspea showed less CF possibly due to very less requirement of inorganic fertilizers (major contributor of GHGs emission)66,67. Conversely, because sole oat required a lot of different inputs, including seed, fertilizer, water, interculture, etc., it showed the highest CF. Yield scaled CF was low in sole grasspea due to less GHGs emission resulting from reduced fertilizer use as well as high system productivity. Low system productivity in sole oat was one of the prime reasons behind maximum CFy from this system. Beneficial role of integrated application of vermicompost and inorganic fertilizer in improvement of system productivity possibly resulted in less CFy68. Reduction of the use of inorganic N fertilizer and use of organic manures especially, vermicompost comparatively lowered down the CF than the 100% RDF and other INM options. Further, the INM comprising vermicompost ensured the maximum system productivity and thus, reduced the yield scaled carbon footprint (CFy). Higher crop productivity reducing the yield scaled carbon footprint was earlier also reported in potato69.

A correlation between carbon intake and carbon footprint (CF) was also observed in the current investigation. Oat showed a high carbon input, but sole grasspea showed a poor carbon input. When comparing CS4 to CS3, an additional row of grasspea was added, which decreased the quantity of seed needed for oat and, as a result, the carbon inputs. The greatest carbon output was achieved in the 3:3 oat + grasspea intercropping system (CS4N3) through the positive impacts of N3 and the biological fixation of grasspea. This was because carbon output was directly linked to total biomass production. Furthermore, carbon efficiency (CE) and the carbon sustainability index (CSI) are essential for sustainable agricultural production in the current climate change environment caused by GHGs’ emissions. A better utilization efficiency of carbon-based inputs is indicative of an effective agricultural system37. It was found that CE and CSI were highest under N3 treatment. High biomass production and less N fertilizer use resulting from use of 75% N through RDF + 25% N through vermicompost perhaps were the reasons behind such findings.

Conclusion

The above study addressed the dearth of previous researches on nutrient management in oat + grasspea intercropping systems and confirmed the efficacy of intercropping system of oat + grasspea (3:3) cultivated with INM having 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost in achieving high system productivity, economics and energy budgeting. Among the oat based cropping system, it showed superiority by generating relatively less carbon footprint and high carbon output, carbon efficiency and carbon sustainability index. Considering the present need of cereal-legume combination under intensive farming scenario, 3:3 oat + grasspea intercropping system, therefore, can be a promising option for cultivation using 75% N through urea + 25% N through vermicompost in Eastern India. Furthermore, additional researches are needed to establish oat + grasspea intercropping system under reduced chemical fertilizer applications without sacrificing system productivity and economic profitability as well as to assure high energy efficiency and less GHGs emissions. The present study is crucial because in Eastern India, rice–wheat is a dominant cropping system and incorporation of underutilized crops like oat and grasspea as intercropping system is a challenge. Moreover, under chemical intensive agriculture, the another challenge is to replace the existing nutrient management with INM. In this context, the findings of this study can provide valuable insights for uplifting the sustainable crop productivity, economic and energetic profitability as well as curbing down the environmental issues through lowering carbon footprint.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article [and its supplementary information file].

References

Puneeth Raj, M. S. & Vyakaranahal, B. S. Effect of integrated nutrient and micronutrients treatment on plant growth parameters in oat cultivar (Avena sativa L.). Int. J. Plant Sci. 9(2), 397–400 (2014).

Biswas, S., Jana, K., Agrawal, R. K. & Puste, A. M. Effect of integrated nutrient management on growth attributing characters of crops under various oat-lathyrus intercropping system. Pharma Innov. J. 8(9), 368–373 (2019).

Iqbal, M. F. et al. Efficacy of nitrogen on green fodder yield and quality of oat (Avena sativa L.). J. Animal Plant Sci. 19(2), 82–84 (2009).

Prabhu, P. L. Green Revolution: Impacts, limits, and the path ahead. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12302–12308 (2012).

Das, A., Sharma, R. P., Chattopadhyaya, N. & Rakshit, R. Yield trends and nutrient budgeting under a long-term (28 years) nutrient management in rice-wheat cropping system under subtropical climatic condition. Plant Soil Environ. 60, 351–357 (2014).

Saha, S. et al. Integrated nutrient management (INM) on yield trends and sustainability, nutrient balance and soil fertility in a long-term (30 years) rice-wheat system in the Indo-Gangetic plains of India. J. Plant Nutr. 41, 2365–2375 (2018).

IPCC. Mitigation of climate change. In: Working Group III contribution to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press (2014).

Shahmohammadi, A., Veisi, H. & Khoshbakht, K. Comparative life cycle assessment of mechanized and semi mechanized methods of potato cultivation. Energy Ecol. Environ. 3, 288–295 (2018).

Selim, M. M. Introduction to the integrated nutrient management strategies and their contribution to yield and soil properties. Int. J. Agron. 2020, 2821678. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2821678 (2020).

Zhang, F. et al. Integrated nutrient management for food security and environmental quality in China. Adv. Agron. 116, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394277-7.00001-4 (2012).

Biswas, S., Jana, K., Agrawal, R. K. & Puste, A. M. Effect of integrated nutrient management on green forage, dry matter and crude protein yield of oat in oat-Lathyrus intercropping system. J. Crop Weed 16(2), 233–238 (2020).

Samreen, S., Shah, Z. & Mohammad, W. Impact of organic amendments on soil carbon sequestration, water use efficiency and yield of irrigated wheat. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 21(1), 36–42 (2017).

Paramesh, V. et al. Integrated nutrient management for improving crop yields, soil properties, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7(10), 3389 (2023).

Bhattacharyya, R., Kundu, S., Prakash, V. & Gupta, H. S. Sustainability under combined application of mineral and organic fertilizers in a rainfed soybean–wheat system of the Indian Himalayas. Eur. J. Agron. 28, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2007.04.006 (2008).

Dugassa, M. The role of cereal legume intercropping in soil fertility management: Review. J. Agric. Aquac. 5(1), 4 (2023).

Ilahi, S. et al. Optimization approach for improving energy efficiency and evaluation of greenhouse gas emission of wheat crop using data envelopment analysis. Sustainability 11, 3409 (2019).

Pervanchon, F., Bockstaller, C. & Girardin, P. Assessment of energy use in arable farming systems by means of an agro-ecological indicator: The energy indicator. Agric. Syst. 72, 149–172 (2002).

Tzanakakis, V. A., Chatzakis, M. K. & Angelakis, A. N. Energetic environmental and economic assessment of three tree species and one herbaceous crop irrigated with primary treated sewage effluent. Biomass Bioenerg. 47, 115–124 (2012).

Esengun, K., Erdal, G., Gunduz, O. & Erdal, H. An economic analysis and energy use in stake-tomato production in Tokat province of Turkey. Renew. Energy 32, 1873–1881 (2007).

Rezvani, M. P., Feizi, H. & Mondani, F. Evaluation of tomato production systems in terms of energy use efficiency and economical analysis in Iran. Not Sci Biol. 3, 58–65 (2011).

Zahedi, M., Eshghizadeh, H. R. & Mondani, F. Energy use efficiency and economical analysis in cotton production system in an arid region: A case study for Isfahan Province. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 4, 43–52 (2014).

Xue, J. F. et al. Carbon and nitrogen footprint of double rice production in Southern China. Ecol. Ind. 64, 249–257 (2016).

Rosenstock, T. S. et al. Agriculture’s contribution to nitrate contamination of Californian groundwater (1945–2005). J. Environ. Qual. 43, 895–907 (2014).

Van Groeningen, K. J., Osenberg, C. W. & Hungate, B. A. Increased soil emissions of potent greenhouse gases under increased atmospheric CO2. Nature 475, 214–216 (2011).

Tjandra, T. B., Ng, R., Yeo, Z. & Song, B. Framework and methods to quantify carbon footprint based on an office environment in Singapore. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 4183–4195 (2016).

Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., & Kenny, D.R. Chemical and microbiological properties. In: Page, A.L. (ed) Methods of soil analysis, Part 2 (2nd ed), Agronomy Monograph No 9, American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society of America, Madison, pp. 199–224 (1982).

Mittal, V. K., Mittal, J. P. & Dhawan, K. C. Research Digest on Energy Requirements in Agricultural Sector. Co-ordinating Cell, AICRP on Energy Requirements in Agricultural Sector (Punjab Agricultural University, 1985).

Sadorsky, P. Modeling and forecasting petroleum futures volatility. Energy Econ. 28, 467–488 (2006).

Devasenapathy, P., Senthilkumar, G. & Shanmugam, P. M. Energy management in crop production. Indian J. Agron. 54, 80–90 (2009).

Nassir, A. J., Ramadhan, M. N. & Ali, A. M. A. Energy input-output analysis in wheat, barley and oat production. Indian J. Ecol. 48(1), 304–307 (2021).

Mandal, K. G., Saha, K. P., Ghosh, P. K., Hatik, M. & Bandyopadhyay, K. K. Bio-energy and economic analysis of soybean-based crop production systems in central India. Biomass Bioenerg. 23, 337–345 (2002).

Singh, H., Mishra, D., Nahar, N. M. & Ranjan, M. Energy use pattern in production agriculture of a typical village in arid zone India: part II. Energy Convers. Manag. 44, 1053–1067 (2003).

Banerjee, H., Sarkar, S. & , Ray, K.,. Energetics, GHG emissions and economics in nitrogen management practices under potato cultivation: A farm-level study. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2, 250–258 (2017).

Pratibha, G. et al. Net global warming potential and greenhouse gas intensity of conventional and conservation agriculture system in rainfed semi-arid tropics of India. Atmos. Environ. 145, 239–250 (2016).

IPCC. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. In: Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., & Midgley, P.M. (eds) Contribution of Working Group I to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 710-716 (2013).

Singh, H., Mishra, D. & Nahar, N. M. Energy use pattern in production agriculture of a typical village in arid zone, India—Part I. Energy Convers. Manag. 43, 2275–2286 (2002).

Lal, R. Carbon emissions from farm operations. Environ. Int. 30, 981–990 (2004).

Pathak, H. & Wassmann, R. Introducing greenhouse gas mitigation as a development objective in rice-based agriculture: I Generation of technical coefficients. Agric. Syst. 94, 807–825 (2007).

Khodi, M., & Mousavi, S.M.J. Life cycle assessment of power generation technology using GHG emissions reduction approach. In: 7th National Energy Conference, 22–23 December 2009, Tehran, Iran, pp A 00219 [in Persian] (2009).

Yadav, G. S. et al. Energy budget and carbon footprint in a no-till and mulch based rice-mustard cropping system. J. Clean. Prod. 191, 144–157 (2018).

Tubiello, F.N., Condor-Golec, R.D., Salvatore, M., Piersante, A., Federici, S., Ferrara, A., Rossi, S., Flammini, A., Cardenas, P., Biancalani, R., & Jacobs, H. Estimating greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture: a manual to address data requirements for developing countries. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. www.fao.org/publications. (Accessed 14 05 2022) (2015).

Pandey, D. & Agrawal, M. Carbon footprint estimation in the agricultural sector. In Assessment of Carbon Footprint in Different Industrial Sectors Vol. 1 (ed. Muthu, S.) (Springer, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-41-2_2.

Chaudhary, V. P. et al. Energy conservation and greenhouse gas mitigation under different production systems in rice cultivation. Energy 130, 307–317 (2017).

Gulles, A. A., Bartolome, V. I., Morantte, R. I. Z. A. & Nora, L. A. Randomization and analysis of data using STAR (Statistical Tool for Agricultural Research). Philippine J. Crop Sci. 39(1), 137 (2014).

Dhakal, D. Effect of maize variety and legume, non-legume intercropping on their yield and cultivation cost in foothills of Nepal. Int. J. Novel Res. Life Sci. 1(1), 1–7 (2014).

Choudhary, V. K. Suitability of maize-legume intercrops with optimum row ratio in mid hills of Eastern Himalaya India. SAARC J. Agri. 12(2), 52–62 (2014).

Mohan, H. M., Chittapur, B. M., Hiremath, S. M. & Chimmad, V. P. Performance of maize under intercropping with grain legumes. Karnataka J. Agric. Sci. 18(2), 290–293 (2005).

Pandita, A. K., Shah, M. H. & Bali, A. S. Effect of row ratio in cereal-legume intercropping systems on productivity and competition functions under Kashmir conditions. Indian J. Agron. 45(1), 48–53 (2000).

Mal, B., Mahapatra, P. & Mohanty, S. Effect of diazotrophs and chemical fertilizers on production and economics of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) cultivars. Am. J. Plant Sci. 5, 168–174 (2014).

Yadav, A. K., Chand, S. & Thenua, O. V. S. Effect of integrated nutrient management on productivity of maize with mungbean intercropping. Global J. Bio-sci. Biotechnol. 5(1), 115–118 (2016).

Sarkar, A., Sarkar, S., Zaman, A. & Devi, W. P. Productivity and profitability of different cultivars of potato (Solanum tuberosum) as affected by organic and inorganic sources of nutrients. Indian J. Agron. 56(2), 159–163 (2011).

Sutaria, G. S., Akbari, K. N., Vora, V. D., Hirpara, D. S. & Padmani, D. R. Response of legume crops to enriched compost and vermicompost on vertic ustochrept under rainfed agriculture. Legume Res. 33(2), 128–130 (2010).

Surve, V. H., Arvadia, M. K. & Tandel, B. B. Effect of row ratio in cereal-legume fodder under intercropping systems on biomass production and economics. Int. J. Agric. Res. Rev. 2(1), 32–34 (2012).

Ray, K. et al. Profitability, energetics and GHGs emission estimation from rice-based cropping systems in the coastal saline zone of West Bengal India. PLoS One 15(5), e0233303. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233303 (2020).

Moerschner, E.J. Stoff- und Energiebilanzen von Ackerbausystemen unterschiedlicher Intensitat – eine Untersuchung an den Rapsfruchtfolgen des Gottinger INTEX-Systemversuchs. Forschungsbericht Agrartechnik, MEG. p. 389 (2000).

Kelm, M., Loges, R. & Taube, F. Ressourceneffizienzokologischer Fruchtfolgesysteme. German J. Agron. 15, 56–58 (2003).

Ozkan, B., Akcaoz, H. & Fert, C. Energy input–output analysis in Turkish agriculture. Renew. Energy 29, 39–51 (2004).

Rathke, G. W. & Diepenbrock, W. Energy balance of winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) cropping as related to nitrogen supply and preceding crop. Eur. J. Agron. 24, 35–44 (2006).

Ghosh, D. et al. Assessment of energy budgeting and its indicator for sustainable nutrient and weed management in a rice-maize-green gram cropping system. Agronomy 11, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11010166 (2021).

Moitzi, G., Wagentristl, H., Kaul, H. P., Bernas, J. & Neugschwandtner, R. W. Energy efficiency of oat: Pea intercrops affected by sowing ratio and nitrogen fertilization. Agronomy 13(1), 42 (2022).

Majeed, Y. et al. Renewable energy as an alternative source for energy management in agriculture. Energy Rep. 10, 344–359 (2023).

Biswas, S., Nwe, L. L., Das, R. & Dutta, D. Effect of integrated nutrient management on nodulation, yield, quality, energetics and economics of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill.] varieties in Eastern India. Legume Res.-An Int. J. 1, 1–9 (2023).

Cheng-Fang, L. et al. Effects of tillage and nitrogen fertilizers on CH4 and CO2 emissions and soil organic carbon in paddy fields of central China. PLoS One 7(5), e34642 (2012).

Tongwane, M. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from different crop production and management practices in South Africa. Environ. Dev. 19, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2016.06.004 (2016).

DeForest, J. L., Zak, D. R., Pregitzer, K. S. & Burton, A. J. Atmospheric nitrate deposition, microbial community composition, and enzyme activity in Northern hardwood forests. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 68, 132–138 (2004).

Hassan, M. U. et al. Management strategies to mitigate N2O emissions in agriculture. Life (Basel) 12(3), 439 (2022).

Walling, E. & Vaneeckhaute, C. Greenhouse gas emissions from inorganic and organic fertilizer production and use: A review of emission factors and their variability. J. Environ. Manag. 276, 111211 (2020).

Billore, S. D., Vyas, A. K. & , Joshi, O.P.,. Effect of integrated nutrient management on productivity, energy-use efficiency and economics of soybean (Glycine max)-wheat (Triticum aestivum) cropping system. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 75(10), 644–646 (2005).

Choudhary, A. K. et al. Influence of integrated crop management technology on potato productivity, profitability, energy dynamics and carbon footprints in north-western Himalayas. Potato J. 48(2), 148–160 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B. carried out the research. S.B. and R.D. wrote the main manuscript text and A.P. guided the research work. K.J. conceptualized the research. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Biswas, S., Das, R., Jana, K. et al. Integrated nutrient management on oat + grasspea intercropping system: an evaluation of system productivity, economics, energetics and carbon footprint. Sci Rep 14, 19414 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66107-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66107-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Standardization of Organically Chickpea Cultivation in Red and Lateritic Soils Through Sole and Combined Uses of Bulky Organic Manures

Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition (2024)