Abstract

To assess the impact of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol in children undergoing corrective surgery for congenital scoliosis. A retrospective analysis was conducted on children undergoing surgical correction for congenital scoliosis, with participants categorized into either the ERAS group or the control group. Comparative evaluations were made across clinical, surgical, laboratory, and quality of life parameters. Following propensity score matching, 156 patients were analyzed. Within the initial 3 days following surgery, the ERAS cohort demonstrated lower pain intensity and exhibited higher daily oral intake compared to their counterparts in the control group. A mere 14.1% of patients in the ERAS group experienced a peak body temperature exceeding 38.5°, illustrating a significantly lower incidence compared to the 33.3% recorded in the control group. The ERAS cohort displayed expedited timeframes for the onset of initial bowel function and postoperative discharge when contrasted with the control group. Levels of IL-6 assessed on the third day post-surgery were markedly reduced in the ERAS group in comparison to the control group. Noteworthy is the similarity observed in postoperative hemoglobin and albumin levels measured on the first and third postoperative days between the two groups. Assessments of quality of life using SF-36 and SRS-22r questionnaires revealed comparable scores across all domains in the ERAS group when juxtaposed with the control cohort. ERAS protocol has demonstrated a capacity to bolster early perioperative recovery, alleviate postoperative stress responses, and uphold favorable quality of life outcomes in children undergoing corrective surgery for congenital scoliosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital scoliosis is a common spinal deformity in children, with an incidence rate of about 1/10001. This type of deformity, characterized by rapid progression, often results in a coronal positioning of the patient's spine. Due to the imbalance in sagittal growth, most patients require early intervention and surgical treatment. The primary surgical approach in clinical practice is spinal surgery involving posterior column osteotomy, orthopedic bone grafting, fusion, and internal fixation. While this method effectively corrects deformities and restores spinal alignment, it is technically challenging and associated with significant intraoperative blood loss. Additionally, young children with incomplete physical development may exhibit poor surgical tolerance and face increased perioperative risks compared to adults2,3.

In recent years, there has been a growing focus on enhancing perioperative management to improve patient outcomes, reduce postoperative stress responses, and facilitate early recovery through the implementation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols. The utilization of ERAS in orthopedic practices, including trauma orthopedics, spinal surgery, and joint surgery, has been on the rise. However, it is important to note that current ERAS guidelines and management plans primarily target adult orthopedic patients4.

Although previous studies have provided limited evidence indicating that ERAS may reduce direct costs and hospital length of stay in pediatric spinal surgery5,6,7,8,9,10,11, the majority of these studies have focused on adolescent patients (age > 14 years). It is important to recognize that children and adolescents may exhibit different responses to the same surgical procedure. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of research investigating the use of ERAS specifically in children with congenital scoliosis12. The existing study reported that ERAS implementation was associated with a shorter postoperative hospital stay and lower pain scores in this population. However, this study was constrained by its small sample size and short-term follow-up duration.

Therefore, our objective is to comprehensively assess both the short-term and long-term benefits of implementing ERAS protocols in the perioperative management of children with congenital scoliosis.

Patients and methods

Ethical approval

This study received approval from the Luoyang Orthopedic-Traumatological Hospital Institutional Research Committee, and written informed consent for medical research was obtained from the guardians of all patients prior to initiating treatment. All procedures were conducted in compliance with the appropriate guidelines and regulations.

Patient selection

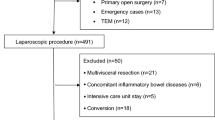

To achieve our research objective, we conducted a retrospective review of medical records of children under 14 years old who underwent surgical treatment for congenital scoliosis between January 2016 and December 2022. The inclusion criteria stipulated that patients should not have had any noticeable neurological dysfunction before surgery and that they underwent posterior spinal osteotomy, orthopedic bone grafting fusion, and internal fixation surgery. Individuals with a history of prior spinal correction or canal surgery were excluded from the study.

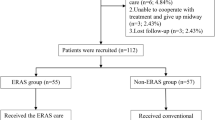

At our institution, the ERAS protocol was implemented as optional practice of traditional procedure in January 2016. The decision to implement ERAS in a particular patient was predominantly influenced by the surgeons’ preference and the wishes of the patient's guardian. A transition period of 2 months was deemed necessary to ensure the complete adoption of the ERAS pathway by all surgeons and staff members. Consequently, patients who underwent ERAS surgery between January 2016 and February 2016 were excluded from the analysis. The eligible patients were divided into two groups: the ERAS group, comprising cases operated on between March 2016 and December 2022, and the non-ERAS group, consisting of patients who underwent surgery from January 2016 to December 2022. Data on demographics, pathology, treatments, complications, and follow-up outcomes were gathered and analyzed.

All participants were asked to complete the SF-36 and SRS-22r questionnaires at least 1 year later at the outpatient clinic. Alternatively, they could provide responses via email, postal mail, WeChat, or other communication channels.

ERAS protocol

The protocol was developed based on established recommendations from the ERAS Society and tailored through internal deliberations13. A multidisciplinary team comprising spinal surgeons, nurses, nutritionists, intensive care specialists, pharmacists, and anesthesiologists collaborated to devise internal procedures and guidelines for the protocol’s implementation.

Figure 1 provides a summary of the ERAS protocol. Key elements of the ERAS pathway encompass preoperative patient education by a dedicated clinic nurse, medical nutritional assessment conducted by a specialized professional using screening tool for the assessment of malnutrition in pediatrics (STAMP), premedication before anesthesia, goal-directed fluid therapy, a preference for avoiding ICU admission when clinically feasible, postoperative multimodal analgesia, and prompt removal of urinary catheters.

Treatment program

All patients were treated under general anesthesia. Pedicle screw internal fixation surgery was performed with continuous monitoring of sensory and motor functions throughout the operation. Motor evoked potential testing was conducted, along with routine autologous blood reinfusion to manage varying levels of blood loss. Postoperatively, antibiotics were administered for a 2-day period to minimize the risk of infection, with adjustments made based on individual patient conditions. Drainage tubes were typically removed 2–3 days following surgery. Patients underwent a comprehensive review with full spine anteroposterior and lateral X-ray imaging 3 to 5 days after surgery. Postoperative bed rest was advised initially, with the possibility of transitioning to braces for mobility on the ground after 1 month.

Outcome variable

Pain assessment was conducted utilizing different tools based on the age of the children13. For individuals aged 7 years and above, pain levels were evaluated using the visual analogue scale (VAS). Alternatively, for patients younger than 7 years, pain assessment was carried out using the FLACC scale, which considers facial expression, leg movement, activity level, cry, and ease of consolability. Regardless of age, pain assessment was undertaken three times daily, with the final reported score representing the mean value across the assessments.

Additional outcome variables encompassed the frequency of the highest body temperature > 38.5 °C recorded over a three-day period following surgery, the length of fasting for water intake during the perioperative phase, postoperative water consumption within the initial 3 days as estimated by parents, and daily food intake expressed as a percentage of regular consumption. Other variables included the timing of the first postoperative ventilation and bowel movement, the length of postoperative hospitalization, the presence of any postoperative complications, as well as the assessment of hemoglobin (Hb), albumin (ALB), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels tested on postoperative days 1 and 3.

Quality of life (QoL) scores were calculated based on the official guideline for SF-36 and SRS-22r questionnaires14.

Statistic analysis

The clinicopathologic variables between the ERAS and non-ERAS groups were initially compared utilizing the Chi-square test. Subsequently, a propensity score-matching (PSM) technique was applied to minimize any discrepancies in clinicopathologic factors between the groups. The matching process involved a 1:1 ratio using the nearest neighbor method. The disparities in pain and QoL between the ERAS and non-ERAS groups were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test, while other outcome variables were compared utilizing either the Chi-square test or the Student t-test. All statistical analyses were conducted using the R 3.4.3 software package, with statistical significance defined as a p-value less than 0.05.

Results

Baseline data

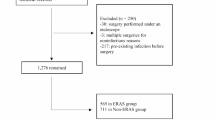

A total of 310 patients were enrolled in the study, comprising 150 (48.4%) male and 160 (51.6%) female individuals, with a mean age of 9 ± 3 years. Only 61 (19.7%) patients presented with a normal age-specific BMI. The classification of deformities revealed failure of vertebral formation in 237 (76.5%) patients, failure of vertebral segmentation in 45 (14.5%) patients, and a mixed deformity in 28 (9.0%) patients. The majority of deformities (n = 203, 65.5%) were located in the thoracic region. A total of 256 (82.6%) patients demonstrated a STAMP score of ≥ 4, and the preoperative Cobb angle was equal to or greater than 45° in 221 (71.3%) patients. When compared to the ERAS group, patients in the control group exhibited a higher prevalence of low BMI (p = 0.029) and preoperative Cobb angle ≥ 45° (p < 0.001), with no significant differences noted in other variables (Table 1). Subsequently, these two significant factors were considered in the calculation of the propensity score at a 1:1 ratio. Subsequently, 156 patients (78 in each group) were selected for further analysis, with no discernible differences observed in clinical variables between the two cohorts (Supplementary Table S1).

Compliance to the ERAS pathway (Table 2)

The overall adherence to the ERAS protocol was high, with rates of 97.4% for preoperative items, 100% for intraoperative items, and 94.8% for postoperative items. In the preoperative pathway, only 8 patients did not consume a carbohydrate-rich drink as recommended. In the postoperative pathway, 6 patients did not undergo early removal of the urinary catheter, and 4 patients could not have early nutrition supply. However, all other items achieved full compliance rates of 100%.

Clinical outcome (Table 3)

On the first day following surgery, the mean VAS score was 2.3 ± 1.2, and the FIACC score was 1.8 ± 0.9 in the ERAS group, both markedly lower than those observed in the control group. Moving to the second day, the ERAS group reported a VAS score of 2.0 ± 1.1 and a FIACC score of 1.6 ± 1.0, whereas the control group experienced heightened pain levels, recording a VAS score of 3.4 ± 1.2 and a FIACC score of 4.6 ± 1.5. By the third day, patients managed under the ERAS protocol reported minimal discomfort, whereas those adhering to traditional procedures still exhibited a VAS score of 1.9 ± 1.2 and a FIACC score of 2.0 ± 1.3.

In the ERAS cohort, body temperature equal to or exceeding 38.5 °C was observed in only 11 individuals (14.1%), a significantly lower rate than the 33.3% noted in the control group (p = 0.005). The mean oral intake in the ERAS group was 15.5% ± 10.5%, 36.8% ± 14.7%, and 75.0 ± 23.6% on the first, second, and third days post-surgery, respectively, all surpassing the values recorded in the control population. Initial bowel movement tended to occur on the third day following surgery in both groups, with no statistically significant difference noted (p = 0.178). However, patients in the ERAS group exhibited a propensity for initial anal exhaust on the first day post-surgery, compared to the second day in the control cohort (p = 0.016). Discharge typically transpired on the seventh day post-surgery for patients in the ERAS group, while those in the control cohort left the hospital on the eighth day, representing a significant distinction (p = 0.025).

Surgical outcome (Table 4)

The mean intraoperative blood loss in the ERAS group was 280 ± 65 ml, a figure comparable to the 300 ± 75 ml recorded in the control population (p = 0.327). The most prevalent complaint postoperatively was nausea and vomiting, followed by abdominal distension, while dizziness was reported least frequently; both groups exhibited a similar distribution of adverse symptoms (all p > 0.05). Postoperative Cobb angle correction to < 6° was achieved in 64 individuals (82.1%) in the ERAS group and 62 individuals (79.5%) in the control group, with no significant difference noted (p = 0.685). Both cohorts attained a comparable rate of spinal correction, with 89.7% in the ERAS group and 87.2% in the control group (p = 0.616).

Laboratory outcome (Table 5)

On the third day post-surgery, the IL-6 level in the ERAS group was notably lower at 18.4 ± 13.3 ng/L, contrasting with the 36.8 ± 30.2 ng/L observed in the control cohort (p < 0.001). Interestingly, both groups displayed akin levels of Hb and ALB on the first and third days, as well as IL-6 on the first day post-surgery (all p > 0.05).

Quality of life (Table 6)

All participants were diligently requested to complete the two questionnaires, yielding a commendable response rate of 100% across both cohorts. Within the SF-36 questionnaire, the domains of physical function, social function, role limitation-physical, and limitation-emotional garnered the highest scores in both groups, while vitality and general health perception scored lower, reflecting a similar pattern in both populations. Impressively, despite these variations, the overall evaluation of the eight domains was akin between the groups.

In terms of the SRS-22r questionnaire, individuals in both cohorts identified function and pain as the most pronounced adverse symptoms. Noteworthy was the high level of satisfaction reported by almost all patients regarding their physical appearance and the treatments received, suggesting favorable mental well-being. Furthermore, the scores across the five domains demonstrated remarkable consistency between the two study groups.

Discussion

Our most important finding was that ERAS demonstrated notable efficacy in ameliorating congenital scoliosis, particularly by mitigating postoperative pain in children undergoing corrective convex surgery. This approach also facilitated a reduction in perioperative fasting times, thereby promoting early recovery of gastrointestinal function, attenuating stress responses, and enhancing overall outcomes. The safe and effective nature of these perioperative interventions for pediatric populations rendered them invaluable for clinical dissemination and adoption.

ERAS encompasses a set of holistic perioperative strategies designed to enhance patient safety, minimize complications, reduce hospitalization duration, and promote rapid recovery15. Key components of ERAS include preoperative patient education, optimized anesthesia, multimodal pain management, and early resumption of oral intake. Over recent years, ERAS protocols have been increasingly applied in adult spinal surgery across various domains like spinal degenerative disorders, spinal fractures, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, and spinal tumors16. Research findings highlight the favorable clinical outcomes of ERAS, which include effective postoperative pain relief, decreased hospital stay, reduced complication rates, and early recovery for patients17,18. While several ERAS clinical guidelines and expert consensuses have been issued worldwide, there is a notable absence of specific ERAS guidelines for pediatric spinal surgery. The distinctive characteristics, challenging disease evaluation, compliance issues, and restricted medication options in pediatric patients necessitate tailored ERAS approaches different from those for adults. To address this gap, we developed a set of 15 ERAS protocols for children with congenital scoliosis, drawing upon pertinent pediatric and spinal surgery guidelines. While some measures, such as fasting time reduction, mirror adult protocols, appropriate modifications were implemented—like avoiding early mobilization to prevent internal fixation failure. Furthermore, given the poor nutritional status often observed in children with spinal deformities, our study introduced preoperative nutritional assessments and advocated high-protein diets. Historically, pediatric surgical ERAS interventions have lagged behind those for adults. A meta-analysis revealed that pediatric ERAS featured an average of only 5.6 interventions, significantly lower than the 23.8 observed for adults19. Our study’s ERAS protocols are comparatively more comprehensive and tailored to children with spinal deformities. Despite a few instances of children refusing preoperative or early postoperative intake, the majority could adhere to the ERAS protocols, reflecting rationality of our ERAS items. Notably, the incidence of complications in both the ERAS and control groups was similar, with no instances of severe complications, underscoring the high feasibility and safety of implementing the ERAS measures outlined in our study.

Perioperative pain management holds a crucial role in the ERAS protocol for spinal surgery. Pain is known to trigger adverse effects such as exacerbating inflammatory responses, compromising coagulation and immune functions, disrupting biological rhythms, and interfering with hormone secretion. Recent studies have underscored the efficacy of multimodal analgesia in alleviating postoperative pain in patients undergoing spinal surgery20. Notably, our study revealed that children in the ERAS group exhibited significantly lower pain scores than those in the control group during the initial 3 days post-surgery. On the first day following surgery, 30 children in the control group experienced moderate pain (pain score > 3), whereas only 6 children in the ERAS group reported similar pain levels. Moreover, a lower proportion of children in the ERAS group exhibited exacerbated pain after discontinuing the analgesia pump, indicating the effectiveness of multimodal analgesia in alleviating postoperative pain in children with congenital spinal deformities. This approach notably diminishes early-stage pain levels in children and mitigates post-discontinuation pain fluctuations—a critical aspect to monitor. Furthermore, aside from multimodal analgesia, the reduced pain levels observed in the ERAS group can also be attributed to the early initiation of feeding in children and the antipyretic properties of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. These additional factors assist in alleviating postoperative irritability induced by hunger and fever in children, enhancing comfort levels, and subsequently minimizing pain scores.

Recent studies have confirmed that allowing both children and adults to consume clear fluids containing carbohydrates 6 h before surgery and drinking water up to 2 h before the procedure effectively alleviates thirst and hunger, prevents dehydration, and does not heighten anesthesia risks21. In our study, we adopted a modified approach to fasting and fluid intake for children during the perioperative period and encouraged early resumption of oral intake post-surgery. The findings demonstrated that children in the ERAS group exhibited improved recovery of diet, increased water intake, and earlier bowel movements compared to those in the control group, with no incidence of serious complications among any child. These results suggest that the ERAS dietary regimen is safe, efficient, and enhances postoperative digestive function recovery in children. At present, while adult spine ERAS guidelines are under development, it is recommended that patients consume 400 mL of clear liquid containing 12.5% carbohydrates 2 h prior to surgery22. Given the substantial variations in physical attributes among children of different ages, we advocate tailoring preoperative clear fluid consumption to individual patient conditions, such as weight. In our study, sweetened beverages were chosen as preoperative drinks for children undergoing ERAS, with most children demonstrating good compliance. However, nine cases were identified where children either refused or did not consume adequate amounts due to taste aversion. In such instances, healthcare providers can consider offering alternative clear beverages based on individual preferences to enhance patient adherence. Since spinal deformity surgery does not directly impact the gastrointestinal tract, we propose that children can resume water intake upon awakening post-surgery.

Surgical intervention is often necessary for children with congenital scoliosis, with procedures like posterior spinal osteotomy, orthopedic bone graft fusion, and internal fixation widely employed in clinical practice. While these surgeries offer precise clinical benefits, they come with challenges such as extensive operation times and significant intraoperative blood loss. Literature reports suggest perioperative blood losses in children can reach up to 42.3% of total blood volume23. Due to developmental and pulmonary abnormalities commonly seen in children with spinal deformities, their surgical tolerance is often compromised. Under traditional perioperative management approaches, children endure prolonged post-surgical stress, hindering optimal recovery and potentially impacting the growth and development of other bodily systems. The stress response triggered by surgery involves trauma-induced inflammation and immune reactions, with IL-6 serving as a key regulator of inflammation, acting as both a pro- and anti-inflammatory agent involved in various physiological processes24. Our study revealed that while IL-6 levels did not significantly differ between the two groups of children on postoperative day 1, levels in the ERAS group were notably lower than those in the control group by day 3 post-surgery. This pattern aligns with the known IL-6 response timeline, where levels begin to rise 1 h post-incision, peak on postoperative day 1, and are closely linked to surgical tissue damage severity and postoperative complications. Despite similar surgical segments, operation durations, and blood loss levels between the groups in our study, the ERAS group’s lower IL-6 levels on day 3 can be attributed to various optimization measures, such as fasting time reduction, intraoperative hypothermia prevention, and multimodal analgesia. These ERAS strategies are effective in mitigating postoperative stress responses, resulting in reduced IL-6 levels compared to the control group. While Hb and ALB levels did not significantly differ postoperatively between the two groups of children in our study, recent studies incorporating tranexamic acid in ERAS management for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients have shown significantly decreased intraoperative blood loss and higher postoperative Hb levels25. Although our study did not utilize tranexamic acid due to the inclusion of many young children, future research could explore its potential benefits. Notably, despite providing high-protein diets during the perioperative period, the substantial surgical trauma, intraoperative blood loss, and extended albumin synthesis cycle resulted in comparable postoperative albumin levels between the ERAS and control groups. This highlights the importance of early nutritional support for children undergoing congenital scoliosis surgeries.

QoL assessment is a crucial component in evaluating the efficacy of the ERAS protocol, yet it has not been extensively explored in prior studies. Our current study may be among the first to investigate whether ERAS offers QoL advantages over traditional procedures. While we did not identify a clear positive correlation, our observations support the notion that children with congenital scoliosis can be successfully managed through surgical correction. The vast majority of patients were able to reintegrate into society with high levels of physical functioning, mental well-being, and minimal adverse symptoms. These findings align closely with those reported by Haapala and colleagues26.

Limitation in current study must be acknowledged, first, there was selection bias within a retrospective study, second, our sample size was relatively small, third, external validation was required before clinical application.

In summary, ERAS demonstrated notable efficacy in mitigating postoperative pain, facilitating a reduction in perioperative fasting times, promoting early recovery of gastrointestinal function, attenuating stress responses, and enhancing overall outcomes in children with correction surgery for congenital scoliosis.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. And the primary data could be achieved from the corresponding author.

References

Menger, R. P. & Sin, A. H. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. 2023. in StatPearls [Internet]. (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2024).

Raitio, A. et al. Hidden blood loss and bleeding characteristics in children with congenital scoliosis undergoing spinal osteotomies. Int. Orthop. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-024-06090-y (2024).

Lefèvre, Y. Surgical technique for one-stage posterior hemivertebrectomy. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 110, 103781 (2024).

Ljungqvist, O. et al. Opportunities and challenges for the next phase of enhanced recovery after surgery: A review. JAMA Surg. 156, 775–784 (2021).

Lambrechts, M. J. et al. Team integrated enhanced recovery (TIGER) protocol after adolescent idiopathic scoliosis correction lowers direct cost and length of stay while increasing daily contribution margins. Mo. Med. 119, 152–157 (2022).

Fabregas, J. A. & Miyanji, F. Short term outcomes of an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway versus a traditional discharge pathway after posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine Deform. 9, 1013–1019 (2021).

Rao, K. E. et al. Introduction of an enhanced recovery pathway results in decreased length of stay in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion: A description of implementation strategies and retrospective before-and-after study of outcomes. J. Clin. Anesth. 75, 110493 (2021).

Jeandel, C. et al. Enhanced recovery following posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A medical and economic study in a French private nonprofit pediatric hospital. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 109, 103626 (2023).

Hengartner, A. C. et al. Impact of a quality improvement initiative and monthly multidisciplinary meetings on outcomes after posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine Deform. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43390-024-00859-2 (2024).

Zhang, D. A., Brenn, B., Cho, R., Samdani, A., Shriners Spine Study Group; Poon, S. C. Effect of gabapentin on length of stay, opioid use, and pain scores in posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A retrospective review across a multi-hospital system. BMC Anesthesiol. 23, 10 (2023).

Shaw, K. A. et al. In-hospital opioid usage following posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Does methadone offer an advantage when used with an ERAS pathway?. Spine Deform. 9, 1021–1027 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Short-term outcomes of an enhanced recovery after surgery pathway for children with congenital scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion: A case-control study of 70 patients. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B. https://doi.org/10.1097/BPB.0000000000001105 (2023).

Crellin, D., Harrison, D., Santamaria, N. & Babl, F. E. Comparison of the psychometric properties of the FLACC scale, the MBPS and the observer applied visual analogue scale used to assess procedural pain. J. Pain Res. 14, 881–892 (2021).

Heemskerk, J. L. et al. Heath-related quality of life and functional outcomes in patients with congenital or juvenile idiopathic scoliosis after an average follow-up of 25 years: A cohort study. Spine J. 24, 462–471 (2024).

Naftalovich, R., Singal, A. & Iskander, A. J. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols for spine surgery: Review of literature. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 54, 71–79 (2022).

Sorour, O., Macki, M. & Tan, L. Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols and spinal deformity. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 34, 677–687 (2023).

Dietz, N. et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) for spine surgery: A systematic review. World Neurosurg. 130, 415–426 (2019).

Pahwa, A., Gong, H. & Li, Y. Enhanced recovery after elective spinal surgery: An Australian pilot study. J. Spine Surg. 10, 30–39 (2024).

Shinnick, J. K. et al. Enhancing recovery in pediatric surgery: A review of the literature. J. Surg. Res. 202, 165–176 (2016).

Simpson, J. C., Bao, X. & Agarwala, A. Pain management in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 32, 121–128 (2019).

Tong, E. et al. Effects of preoperative carbohydrate loading on recovery after elective surgery: A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Nutr. 9, 951676 (2022).

Cheng, P. L., Loh, E. W., Chen, J. T. & Tam, K. W. Effects of preoperative oral carbohydrate on postoperative discomfort in patients undergoing elective surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 406, 993–1005 (2021).

Bao, B., Yan, H. & Tang, J. A review of the hemivertebrae and hemivertebra resection. Br. J. Neurosurg. 36, 546–554 (2022).

Kaur, S., Bansal, Y., Kumar, R. & Bansal, G. A panoramic review of IL-6: Structure, pathophysiological roles and inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 28, 115327 (2020).

Shrestha, I. K. et al. The efficacy and safety of high-dose tranexamic acid in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 16, 53 (2021).

Haapala, H. et al. Surgical and health-related quality of life outcomes in children with congenital scoliosis during 5-year follow-up. Comparison to age and sex-matched healthy controls. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 43, e451–e457 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: L.S., F.W., H.W.; manuscript writing: L.S., F.W., H.W.; studies selecting: L.S., F.W., H.W.; data analysis: L.S., F.W., H.W.; study quality evaluating: L.S., F.W., H.W.; manuscript revising: L.S., F.W., H.W. The final manuscript was read and approved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, L., Wu, F. & Wang, H. Enhanced recovery after surgery in children with congenital scoliosis. Sci Rep 14, 19270 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66476-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66476-1