Abstract

By 2050, 1 in 4 people worldwide will be living with hearing impairment. We propose a digital Speech Hearing Screener (dSHS) using short nonsense word recognition to measure speech-hearing ability. The importance of hearing screening is increasing due to the anticipated increase in individuals with hearing impairment globally. We compare dSHS outcomes with standardized pure-tone averages (PTA) and speech-recognition thresholds (SRT). Fifty participants (aged 55 or older underwent pure-tone and speech-recognition thresholding. One-way ANOVA was used to compare differences between hearing impaired and hearing not-impaired groups, by the dSHS, with a clinical threshold of moderately impaired hearing at 35 dB and severe hearing impairment at 50 dB. dSHS results significantly correlated with PTAs/SRTs. ANOVA results revealed the dSHS was significantly different (F(1,47) = 38.1, p < 0.001) between hearing impaired and unimpaired groups. Classification analysis using a 35 dB threshold, yielded accuracy of 85.7% for PTA-based impairment and 81.6% for SRT-based impairment. At a 50 dB threshold, dSHS classification accuracy was 79.6% for PTA-based impairment (Negative Predictive Value (NPV)-93%) and 83.7% (NPV-100%) for SRT-based impairment. The dSHS successfully differentiates between hearing-impaired and unimpaired individuals in under 3 min. This hearing screener offers a time-saving, in-clinic hearing screening to streamline the triage of those with likely hearing impairment to the appropriate follow-up assessment, thereby improving the quality of services. Future work will investigate the ability of the dSHS to help rule out hearing impairment as a cause or confounder in clinical and research applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization anticipates that 1 in 4 people worldwide will be living with hearing impairment by the year 20501. Recent research by the Lancet Commission showed a direct association between untreated hearing impairment and cognitive impairment, aging-related neurodegeneration, and risk of developing dementia2,3,4,5,6. Hearing impairment in older adults leads to a reduction in social activity and engagement, making it more difficult in some cases to diagnose both hearing loss and cognitive impairment7,8,9. An estimated 8% of dementia cases can be avoided by addressing hearing impairment3. Additional research suggests that a decrease in objective speech-hearing ability is likely to negatively impact a person’s cognitive ability as they age10. Unfortunately, only 14–16% of older adults are regularly screened for hearing impairment7,11, self-reports of hearing loss may not be accurate in populations with/at risk of cognitive impairment, and thus hearing loss is often underdiagnosed.

On average, it takes adults 7–10 years after the onset of their hearing impairment symptoms before seeking a hearing screening and still several more years of delay after the initial screening to receive an intervention to address their hearing issues12,13. This delay in screening is compounded by the low sensitivity of common hearing screening methods. For example, the self-reported Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE) and the Whisper Tests have a sensitivity of 62% and 73%, respectively, and are highly variable as they depend on the test administrator and the listening environment12. Thus, even when an individual is screened, hearing impairment may be missed in a substantial number of cases, further delaying hearing loss intervention. As such, the clinical utility of these screening methods is limited. Anticipating an increase in the global prevalence of hearing impairment, a fast, reliable, repeatable, sensitive, and automated method for screening hearing in older adults is clearly needed7,11.

Digital solutions may be a more viable solution for addressing hearing screening problems by providing a ubiquitous and scalable option, which can be readily integrated into various clinical and research workflows. Such solutions, however, also have limitations that hinder their wide adoption. Many digital hearing screening methods mimic standard audiometric determination of pure tone threshold averages (PTAs) by presenting a steady tone13,14. These PTAs are often used to infer speech-hearing ability, a practice that is not reliable given that they often fall between 8 and 16 dB quieter than standardized audiometric speech recognition thresholds (SRTs)13,14,15,16,17. Current methods that implement speech hearing evaluate an individual’s hearing of numbers or real words13,18. This presents a challenge in the context of cognitive screening where numbers are often parts of neuropsychological evaluations, and this practice has potential interference effects on subsequent testing13. Many cognitive tests require encoding and repetition of verbal stimuli, and thus other hearing tests seeking to establish normal hearing with real-word stimuli prior to the administration of cognitive testing introduce potential interference with verbal memory tasks. Adult hearing screening is in need of a solution that can be quickly administered and interpreted, objectively evaluates the individual’s speech-hearing ability, and can be used without impacting cognitive screening.

To address these gaps, a digital speech hearing screener (dSHS) was developed as an accompaniment to the Digital Clock and Recall (DCR), a brief digital cognitive assessment. The DCR consists of an immediate recall of three words, followed by the DCTclock™ drawing command and copy clock conditions, and finally the delayed recall of the same three words19,20,21. The patient’s or participant’s ability to perform the DCR critically depends upon the patient’s or participant’s accurate perception of the target words, thus an assessment of the person’s ability to hear the instructions and three-word recall is critical. We propose a dSHS that does not rely on pure tones but instead requires the recognition of short nonsense words, to better understand an individual’s speech-hearing ability. Two-syllable, vowel-consonant–vowel nonsense words with a diversity of high-frequency speech sounds (i.e., “s, t, f, z, sh” etc.) were used as stimuli to reduce the potential interference with subsequent behavioral or cognitive testing. This differs from other digital hearing screenings which use real-word, numbers, or sequences introducing the potential for intrusion effects in subsequent testing of cognition or behavior. The main objectives of this cross-sectional observational study were to compare the hearing thresholds automatically calculated by the dSHS to the results of a clinical audiogram (pure tones and speech recognition) and examine the relationship between these thresholds. Furthermore, we report classification analysis of the mild impairment clinical standard threshold of 35 dB and the moderate impairment threshold of 50 dB.

Methods

Study sample

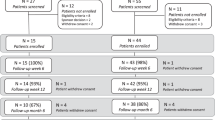

50 participants were enrolled as part of a clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05848804) at a single site (Crossover Management, Wake Forest, NC) over 11 months. All Participants were 55 years of age or older, and fluent in English. Participants were excluded if they were unable to understand or unwilling to comply with testing instructions, reported a major psychiatric disorder such as bipolar disorder, or if they had major medical problems such as cancer or epilepsy. Hearing tests were administered by a trained hearing instrumentation specialist after obtaining informed consent from each subject. Study procedures were approved by an independent Institutional Review Board (Advarra IRB Inc., Columbia, MD; www.advarra.com/) and were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. Each participant was assigned (using the 4-block randomization method shown in Fig. 1) to one of two groups: the first group completed the audiogram first and then the dSHS, whereas the second group completed the dSHS first and then the audiogram. Equal numbers of participants were enrolled in each study arm.

Mobile device sound output calibration

The dSHS and cognitive assessment battery were conducted using an iPad Pro (11ʺ, 4th Generation, Wi-Fi, Apple, Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA). Sound levels produced by the iPad Pro were measured using a Type 2 calibrated SPL meter set to the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standards for electroacoustic devices (IEC 61672-1 class2, IEC651 Type2, ANSI14 Type2) placed 1 foot from the mobile device. Study participants were tested in a quiet environment testing center. Calibration is vital for comparison between the sound output levels of devices and for the threshold comparisons (PTA, SRT, and dSHS) made in this study to those of similarly calibrated devices used for audiometric assessment in the clinic.

Study protocol

Pure tone average (PTA) thresholds were established at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz tones using Interacoustics AA222 (Model 1078; firmware version 1.11). While other tones were tested, the inclusion of 3000 & 4000 Hz did not have a significant effect the outcomes in our models and thus were not included in the analysis. Speech recognition thresholds (SRT) were established during audiometric testing as the lowest levels at which pre-recorded speech (spondee words; i.e., cowboy, hotdog, cupcake, etc.) presented at a consistent intensity could be recognized with at least 50% accuracy15,16,22,23. Importantly, the authors and creators of the hearing screener recognize that clinical environments can be noisy. The dSHS thus performs an environmental noise level check prior to the beginning of the screening. This noise level check does not allow the user to proceed to the hearing screening if the environmental noise level is measured as higher than 35 dB.

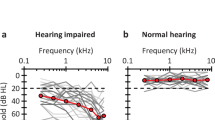

The dSHS used nonsense words to avoid potential intrusion effects on subsequent cognitive testing. In the dSHS, a short, nonsense vowel–consonant–vowel (VCV) word was presented by the mobile device’s external speakers (Fig. 2). Participants were asked to select from a list of 6 nonsense VCV words randomly selected from a constrained list, the one that best matched what they heard. If they did not hear or understand the word, participants were instructed to select “Didn’t Hear”, which was considered an incorrect response. The volume was increased incrementally in steps of 6.25% on the tablet following every incorrect response. The participant performed this task with several randomly selected VCV words until three consecutive correct responses were obtained. Therefore, if participants normally wore hearing aids (n = 23), they were instructed to wear them during the assessment to mimic their normal hearing conditions as closely as possible. All hearing tests were performed in a noise-attenuated booth designed for hearing screening (environmental noise level < 35 dB). In cases where environmental noise is > 35 dB, users are not able to begin the dSHS until noise sources are removed or attenuated. Data collected included correct/incorrect responses to the auditory stimuli and the subsequent increase or maintenance in volume. The iPad tablet was maintained steady at on a fixed arm 30 cm from the person being tested while the participant sat in a high-back chair.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted in Matlab v9.3 (Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to determine if there was a linear relationship between the average PTA and the volume level established by the hearing screener task. PTA thresholds were adapted to fit the nearest standards of hearing impairment established by the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association24 (ASHA). Normal hearing was classified as the reported average loudness of conversational speech25. Impaired hearing was classified using adapted thresholds for severe and profound hearing impairment25. The maximum value of the audiogram response for the three frequencies was considered an outcome measure; however, PTA was used given its status as the standard clinical measure of hearing impairment. In cases where a difference between left and right ears existed on either PTA or SRT, the worse threshold was used in our analysis to avoid overestimating hearing ability.

One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to determine if there was a significant difference between Impaired and Unimpaired groups by the dSHS, where a clinical threshold of moderately impaired hearing24 was used to determine impaired hearing. Two different thresholds to identify the presence of hearing impairment, optimized for distinct contexts, were examined in this study. Each threshold was used to perform a binary classification analysis to determine the dSHS performance in classifying hearing impairment. The first threshold, 35 dB, was based on the clinical standard for differentiating normal hearing from hearing impairment26. The second threshold, 50 dB, was intended to maximize the negative predictive value (NPV) in order to optimize the ruling-out greater than moderate hearing impairment. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) was calculated to examine the discriminative ability of the dSHS between the Impaired and Unimpaired classes24.

To evaluate the performance of the dSHS in classifying hearing impairment, we used Classification accuracy (Acc) defined as the percentage of participants correctly classified as being impaired or not-impaired. The sensitivity (Sens) is defined as the percentage of participants classified correctly. Similarly, specificity (Spec) is defined as the percentage of impaired participants, correctly identified as such by the system. Positive and negative predictive values were also calculated to provide a measure of the predictive power of positive and negative (Impaired or Unimpaired) classifications. The positive predictive value (PPV) is defined as the proportion of participants, classified as impaired by the system, who were correctly classified. The negative predictive value (NPV) is the proportion of participants, classified as Unimpaired by the system, who are correctly classified. (The data that support the findings of this study are available from R.B. with the permission of Linus Health Inc.).

Results

A total of 50 participants (28 females, mean age ± SD: 73.64 ± 9.5 years) completed the hearing screener protocol. On average, the dSHS duration was 2 min 46 s (± 53 s). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was 0.77 (p < 0.001) between the dSHS results and the PTA audiometric testing and 0.78 (p < 0.001) between the dSHS results and SRT (Fig. 2). Results of a One-way ANOVA showed significant differences in dSHS volumes between the hearing impaired and hearing unimpaired classes as determined by audiogram PTAs and SRTs (F = 38.1, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3).

To assess the classification performance of the dSHS in determining hearing impairment, confusion matrices were constructed by applying a priori thresholds (35 and 50 dB) to the PTA’s and SRT’s. Results of the standard hearing impairment threshold (35 dB) model revealed an overall classification accuracy for the dSHS determining PTA-based impairment of 85.7% (Sensitivity = 87.9%; positive predictive value; PPV = 90.6%; NPV = 76.5%; AUC = 0.87) and 81.6% (Sensitivity = 92.9%; PPV = 90.6%; NPV = 76.5%; AUC = 0.85) on SRT-based impairment (Table 1, Fig. 4). To evaluate the concordance between the dSHS, PTA, and SRT thresholds, the percentage of agreement and associated Cohen’s Kappa statistics were evaluated. The agreement among the dSHS, PTA, and SRT was strong (79–85%; K: 0.44–0.68)27.

Distributions of dSHS volumes for 50 participants grouped by Pure Tone Averages (PTA; top row figures) and Speech Recognition Thresholds (SRT; bottom row figures). Figures on the left (top and bottom) show distributions at a hearing impairment cutoff threshold of 35 dB while figures on the right show distributions at a hearing impairment cutoff threshold of 35 dB. *Gray shaded boxes indicate upper and lower quartiles above and below the bolded median line.

Results of the model optimized for NPV as a threshold suited to rule out potentially severe impairment (50 dB) revealed an overall classification accuracy of 79.6% for the dSHS determining PTA-based impairment (Sensitivity = 85.7%; PPV = 60.6%; NPV = 93.1%; AUC = 0.84) and 83.7% (Sensitivity = 100%; PPV = 60%; NPV = 100%; AUC = 0.87) for SRT-based impairment (Table 1, Fig. 4)24,26.

Results of area under the curve ROC analysis (Fig. 5) showed excellent ability of the dSHS to predict audiogram pure tone and speech recognition thresholds at both 35 dB (0.87 and 0.90 respectively) and 50 dB (1.0 and 0.98 respectively).

Discussion

We report the performance of a novel method of screening for hearing impairment in older adults. To our knowledge, this mobile speech-hearing screener is the first digital assessment of its kind to directly compare calibrated mobile device non-word speech volumes to both standardized speech recognition and pure tone audiometry. While other methods developed use spondee words, numbers, or other real words to establish hearing thresholds, the current work used nonsense words as stimuli to avoid potential interference with cognitive testing likely to be performed in primary care or specialist settings. This work introduces an alternative screening method to tedious pure tone and speech recognition audiometry. The dSHS provides a time-saving, efficient method for screening hearing in adults that allows for easy integration into clinical workflows and immediate reporting of results. Significant differences in dSHS results were demonstrated between impaired and unimpaired hearing groups, as determined by professionally administered pure-tone and speech recognition audiometric testing. The results of this study further suggest that our dSHS is sensitive enough to identify individuals classified as impaired on both standardized pure tone and speech recognition audiometry.

Classification analysis, using thresholds optimized for separate contexts, revealed that the dSHS has excellent sensitivity in classifying impaired hearing at both the mild impairment clinical standard threshold of 35 dB and the moderate impairment threshold of 50 dB26. Strong agreement was present between the dSHS, PTA, and SRT classification based on both 35 and 50 dB cutoffs, indicating high concordance between the two methods of hearing evaluation. Importantly, the dSHS not only classified the clinical standard PTA-based impairment but also was sensitive to impairment on SRT-based impairment (Table 1). This is important because, despite being highly correlated in our sample, PTAs and SRTs are not equivalent, and can show high variability across individuals12,15,16,22,23. In addition, it can be difficult to access SRTs in standard clinical practice.

In the context of cognitive screening, reliance on pure-tone tests alone may negatively impact the outcome of cognitive testing given that thresholds are generally higher for speech recognition than for pure-tone recognition. This is a concern for people with hearing impairment because a cognitive test becomes both a test of hearing and a test of cognition when pure tone thresholds are used as the benchmark for a person’s speech-hearing ability16,23. In other words, cognitive ability is confounded by speech-hearing ability in individuals with hearing impairment. Thus, in these people, a pure tone test will not fully represent their hearing abilities. In fact, research suggests that despite the high correlation between pure tone thresholds and speech recognition thresholds, SRTs tend to be 8–16 dB higher than PTAs on average12,15,16,22,23. As such, speech-hearing ability should not be inferred from pure tone thresholds alone.

Our second classification analysis optimized the NPV of the dSHS and was intended to provide test administrators with insights about when hearing impairment in a screened patient could be reliably ruled out, up to a specified degree. Our results indicate that passing the dSHS at or below 50% of the device volume reliably rules out hearing impairment greater than moderate levels based on a 50 dB cutoff.

At an average duration of 2 min 46 s, results indicate that the novel dSHS is consistent with the results of audiometric testing. This brief assessment can be self-administered using a commercial-off-the-shelf device, which contributes to its usability and acceptability in standard clinical practice. Unlike other available methods of adult hearing screening, the dSHS described in this work does not rely on the use of headphones and can be administered using the speakers of a mobile device. Importantly, the ability to screen for hearing impairment in under 3 min and reliably infer that an individual does not have greater moderate or severe hearing impairment can facilitate the broad screening of hearing deficits, which can streamline treatment and contribute to a substantial reduction of dementia cases in the future. Furthermore, cognitive tests that deliver auditory stimuli or instructions may be confounded by hearing impairments, and thus, a workflow-friendly hearing screener can also improve the accuracy of cognitive assessments28,29.

Several limitations of this study and directions for future research exist. Future research will include a larger sample size to further validate the concordance of hearing-impairment classifications by the dSHS, SRT, and PTA in an independent sample. More work will also need to be done to validate the hearing screener in languages other than English. Lastly, the current study only determined the hearing impairment threshold for a single mobile device model (11″ iPad Pro). However, in future work, this methodology can be extended to incorporate a broader range of devices and operating systems by ensuring accurate calibration between the volume level and audiometric thresholds to allow for differing volume levels and increase the availability of the dSHS in a larger number of mobile devices.

Conclusion

The Linus Health digital speech hearing screener (dSHS) successfully differentiates between hearing impaired and hearing unimpaired individuals and does so in under 3 min. This mobile digital speech-hearing is compared directly to calibrated mobile device volumes to both standardized speech recognition and pure tone audiometry. This novel, digital method for hearing screening provides a means to quickly and easily screen for hearing impairment for various clinical and research purposes. With a rapidly aging global population, cognitive testing for older adults will be a critical part of the healthcare system. Given the known intricate relationship between hearing ability and cognition, the results of this digital speech hearing screener may be used in future work to rule out hearing impairment as a cause, confounding factor, or co-morbidity of cognitive impairment.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon reasonable request to author RB through Linus Health Inc.

References

WHO. 1 in 4 People Projected to have Hearing Problems by 2050. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2021-who-1-in-4-people-projected-to-have-hearing-problems-by-2050 (Accessed 13 June 2023).

Davies, H. R., Cadar, D., Herbert, A., Orrell, M. & Steptoe, A. Hearing impairment and incident dementia: Findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 65(9), 2074–2081. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14986 (2017).

Jiang, F. et al. Association between hearing aid use and all-cause and cause-specific dementia: An analysis of the UK Biobank cohort. Lancet Public Health 8(5), e329–e338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00048-8 (2023).

Loughrey, D. G., Kelly, M. E., Kelley, G. A., Brennan, S. & Lawlor, B. A. Association of age-related hearing loss with cognitive function, cognitive impairment, and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 144(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2513 (2018).

Ralli, M. et al. Hearing loss and Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Int. Tinnitus J. 23(2), 79–85 (2019).

Wei, J. et al. Hearing impairment, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 7(3), 440–452. https://doi.org/10.1159/000485178 (2017).

Davis, A. C. & Hoffman, H. J. Hearing loss: Rising prevalence and impact. Bull. World Health Organ. 97(10), 646-646A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.19.224683 (2019).

Graydon, K., Waterworth, C., Miller, H. & Gunasekera, H. Global burden of hearing impairment and ear disease. J. Laryngol. Otol. 133(1), 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215118001275 (2019).

Wayne, R. V. & Johnsrude, I. S. A review of causal mechanisms underlying the link between age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline. Ageing Res. Rev. 23, 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.06.002 (2015).

Moore, D. R. et al. Relation between speech-in-noise threshold, hearing loss and cognition from 40–69 years of age. PLoS ONE 9(9), e107720. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107720 (2014).

Deafness and Hearing Loss. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (Accessed 2 August 2023).

Preece, J. & Fowler, C. Relationship of pure-tone averages to speech reception threshold for male and female speakers. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 3, 221–224 (1992).

Use of Mobile Phone Based Hearing App Hear WHO for Self Detection of Hearing Loss|Opast Publishing Group. https://www.opastpublishers.com/peer-review/use-of-mobile-phone-based-hearing-app-hear-who-for-self-detection-of-hearing-loss-5282.html (Accessed 26 July 2023).

Yesantharao, L. V., Donahue, M., Smith, A., Yan, H. & Agrawal, Y. Virtual audiometric testing using smartphone mobile applications to detect hearing loss. Laryngosc. Investig. Otolaryngol. 7(6), 2002–2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.928 (2022).

Picard, M., Banville, R., Barbarosie, T. & Manolache, M. Speech audiometry in noise-exposed workers: The SRT-PTA relationship revisited. Audiology 38(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.3109/00206099909073000 (1999).

Ristovska, L., Jachova, Z., Kovacevic, J., Radovanovic, V. & Hasanbegovic, H. Correlation between pure tone thresholds and speech thresholds. J. Hum. Res. Rehabil. 11, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.21554/hrr.092108 (2021).

Hammond, E. A. & Diedesch, A. C. Usability and perceived benefit of hearing assistive features in Apple AirPods Pro. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 153, A155. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0018485 (2023).

Swanepoel, D. W., De Sousa, K. C., Smits, C. & Moore, D. R. Mobile applications to detect hearing impairment: Opportunities and challenges. Bull. World Health Organ. 97(10), 717–718. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.18.227728 (2019).

Rentz, D. M. et al. Association of digital clock drawing with PET amyloid and tau pathology in normal older adults. Neurology 96(14), e1844–e1854. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011697 (2021).

Souillard-Mandar, W. et al. Learning classification models of cognitive conditions from subtle behaviors in the digital clock drawing test. Mach Learn. 102(3), 393–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-015-5529-5 (2016).

Souillard-Mandar, W. et al. DCTclock: Clinically-interpretable and automated artificial intelligence analysis of drawing behavior for capturing cognition. Front. Dig. Health 3, 750661. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2021.750661 (2021).

Vermiglio, A. J., Soli, S. D., Freed, D. J. & Fang, X. The effect of stimulus audibility on the relationship between pure-tone average and speech recognition in noise ability. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 31(3), 224–232. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.19031 (2020).

He, L. P. Relation between pure tone audiometry and speech audiometry in various hearing-impaired listeners. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi 28(1), 29–31 (1993).

Alshuaib, W. B. et al. Classification of hearing loss. In Update on Hearing Loss (eds Alshuaib, W. B. et al.) (IntechOpen, 2015).

Olsen, W. O. Average speech levels and spectra in various speaking/listening conditions. Am. J. Audiol. 7(2), 21–25. https://doi.org/10.1044/1059-0889(1998/012) (1998).

Olusanya, B. O., Davis, A. C. & Hoffman, H. J. Hearing loss grades and the International classification of functioning, disability and health. Bull. World Health Organ. 97(10), 725–728. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.19.230367 (2019).

McHugh, M. L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 22(3), 276–282 (2012).

Yuan, J., Sun, Y., Sang, S., Pham, J. H. & Kong, W. J. The risk of cognitive impairment associated with hearing function in older adults: A pooled analysis of data from eleven studies. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 2137. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20496-w (2018).

Lin, F. R. et al. Hearing intervention versus health education control to reduce cognitive decline in older adults with hearing loss in the USA (ACHIEVE): A multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01406-X (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.B—Study conceptualization, Acquisition of data, Definition of aims of the analysis; Major role in the design of analysis and interpretation of data; Drafting and revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; Approval of final version of the manuscript. B.R.G—Major role in the design of analysis; Analysis and interpretation of data; Drafting and revision of the manuscript for content; Approval of the final version of the manuscript. I.M.—Study investigation; Clinical trial study coordinator; Interpretation of data; Acquisition of data; Drafting and revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; Approval of final version of the manuscript. M.C.—Interpretation of data; Drafting and revision of the manuscript for content; Approval of the final version of the manuscript. D.W.—Principal Investigator and data collection; Approval of the final version of the manuscript. J.G.—Drafting and revision of the manuscript for content; Approval of the final version of the manuscript. A.J.—Interpretation of data; Revision of the manuscript for content; Approval of the final version of the manuscript. J.S.—Interpretation of data; Revision of the manuscript for content; Approval of the final version of the manuscript. D.B.—Interpretation of data; Revision of the manuscript for content; Approval of the final version of the manuscript. S.T—Interpretation of data; Revision of the manuscript for content; Approval of the final version of the manuscript. A.P.L.—Conception and definition of aims of the analysis; Revision of the manuscript for content; Approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

DB is a co-founder of Linus Health and declares ownership of shares or share options in the company. RB, BG, IM, MC, JGO, AJ, ST, and JS are employees of Linus Health and declare ownership of shares or share options in the company. Author DW does not have any competing interests to declare. APL is a co-founder of Linus Health and TI Solutions and declares ownership of shares or share options in the company. APL serves as a paid member of the scientific advisory boards for Neuroelectrics, Magstim Inc., TetraNeuron, Skin2Neuron, MedRhythms, and Hearts Radiant, and is listed as an inventor on several issued and pending patents on the real-time integration of transcranial magnetic stimulation with electroencephalography and magnetic resonance imaging, applications of noninvasive brain stimulation in various neurological disorders, as well as digital biomarkers of cognition and digital assessments for early diagnosis of dementia.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Banks, R., Greene, B.R., Morrow, I. et al. Digital speech hearing screening using a quick novel mobile hearing impairment assessment: an observational correlation study. Sci Rep 14, 21157 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67539-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67539-z