Abstract

The crystal of [C(NH2)3]2Zn(SO4)2 guanidine zinc sulfate was grown and its structure, dilatometric, dielectric, elastic and piezoelectric properties were studied in a broad temperature range, covering the phase transition point. The crystal undergoes a continuous phase transition at 178 K from the room temperature tetragonal phase with a space group \(\text{I}\overline{4}2\text{d }\) to the tetragonal low temperature phase with a space group \(\text{I}\overline{4 }\). The structural X-ray studies allowed proposing molecular mechanism associated with the rearrangement in the configuration of N–H⋯O hydrogen bonds and reorientation of guanidine cations in the structure, leading to a change in the symmetry of the low temperature phase. Results of thermal expansion and dielectric studies are typical of a structural nonferroelectric continuous transition. Also measurement of piezoelectric and elastic properties revealed small anomalies at 178 K. Below the transition temperature, a new piezoelectric component, that is a ferroelastoelectric macroscopic order parameter, was found.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intensive efforts are underway to search for new materials with increasingly advanced properties, to be used in energy converters, various sensors, optoelectronics, etc. Particularly interesting are ferroic materials whose physical properties are changed by a specific external factor. The primary ferroicity, in historical order, includes ferromagnetism—18721, ferroelectricity—19202, and ferroelasticity—19733. In the low-temperature phase, the order parameters include spontaneous magnetization, electric polarization, and mechanical deformation. Their sign can be reversed by external magnetic, electric, or mechanical stress fields. A characteristic feature of the first-order ferroics (also called primary ferroics) is that their orientational states are described by tensors of the lowest rank and exhibit characteristic hysteresis loops. The occurrence of ferromagnetic properties in the low-temperature phase does not necessarily involve a change in symmetry, while the necessary condition for ferroelectricity is the existence of a polar axis of symmetry. On the other hand, spontaneous deformation requires a reduction in the rank of the crystallographic system. Materials in which the sign of the order parameter can be reversed by the simultaneous action of two external fields are called second-order or secondary ferroics. This group includes ferroelastoelectrics, ferroelastomagnetics, ferromagnetoelectrics, ferrobimagnetics, ferrodielectrics, and ferrobielastics4,5. Particularly interesting is the ferroelastoelectric ordering. The necessary condition for realization of this ordering is the reduction of symmetry to a noncentrosymmetric nonpolar point group without changing the crystallographic system. Thus, in the low-temperature phase, the order parameter consists of the appropriate components of the spontaneous piezoelectric effect tensor. Its sign can be reversed by simultaneous application of an electric field and mechanical stress in the appropriate directions.

In scientific literature, information can be found on several hundred substances exhibiting ferroelectric or ferromagnetic ordering. However, so far, only a dozen materials are known to exhibit ferroelastoelelectric ordering. All of them are inorganic crystals with ionic bonds, and their high-temperature phase does not exhibit the piezoelectric phenomenon. In the few studies in which a spontaneous piezoelectric effect was observed, its temperature dependence was not presented. The zinc guanidine sulfate crystal [C(NH2)3]2Zn(SO4)2 (abbreviated GZS) we studied is a mixed inorganic–organic compound and the only one known to exhibit the piezoelectric high-temperature phase. Its crystal structure was solved at room temperature in 1970, and its space group is \(\text{I}\overline{4}2\text{d }\) 6. The crystal has been fully characterized at room temperature: its elastic, electrostrictive, and electro-optical properties7 have been determined and its FTIR spectrum8, electron paramagnetic resonance9, Raman scattering10, and optical absorption edge11 have been analyzed.

For the first time, a phase transition in the range of 170 ÷ 180 K was discovered in the GZS crystal by Bohatý et al.12. Its existence at 178 K and its type have been confirmed in studies of complex dielectric permittivity and specific heat13. X-ray scattering studies have shown that the phase transition at 178 K is accompanied by a change in the point symmetry from \(\overline{4}\)2 m to \(\overline{4}\), with no change in the tetragonal system14. Such a symmetry change indicates that ferroelastoelectric and ferrobielastic ordering may appear in the low-temperature phase.

The first crystal whose properties were confirmed through the study of the piezoelectric phenomenon was ammonium chloride, in which the symmetry in the cubic system decreased from m3m to \(\overline{4}\)3 m at 242 K15.

So far about 20 crystals are known to exhibit ferroelastoelectric ordering in the low-temperature phase, but only in a few this transition occur with no change in the tetragonal system. In Table 1 we presented possible transitions to the ferroelastoelectric phase within the tetragonal system.

In the tetragonal system in which GZS crystallizes, the following compounds should exhibit ferroelastoelectric ordering in the low-temperature phase:

-

TeO2—4/mmm → 422, TC = 1075 K16

-

Ag2HgI4—\(\overline{4}\)2 m → \(\overline{4}\), TC = 330 K17

-

(NH4)2CuCl4·2H2O—4/mmm → \(\overline{4}\)2 m, TC = 200 K18,19

-

(NH4)2CuBr4·2H2O—4/mmm → \(\overline{4}\)2 m, TC = 158 K20,21

Only in the dehydrated crystals of ammonium tetrachlorides, a temperature-dependent spontaneous piezoelectric effect has been measured in the ordered phase.

In these crystals, the high-temperature phase is centrosymmetric, and the piezoelectric effect appears only below the phase transition. However, the GZS crystal exhibits piezoelectric properties in both phases. In the high-temperature phase with point symmetry \(\overline{4}\)2 m, there are 3 components of the piezoelectric tensor: d14 = d25, d36, and 9 components of the elastic tensor: c11 = c22, c33, c44 = c55, c66, c12, c13 = c23 (Voigt’s notation). In the low-temperature phase with symmetry \(\overline{4}\), additional components of the piezoelectric tensor appear: d31 = d32, d15 = − d24, and the elastic tensor component c16 = − c2622. Such a change in symmetry is a necessary condition for the existence of the ferroelastoelectric phase. The goal of the study reported in this paper is to demonstrate the existence of additional piezoelectric components, investigate their temperature dependence, and prove that they are parameters of ferroelastoelectric ordering.

Experimental and results

Crystal structure

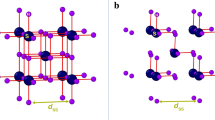

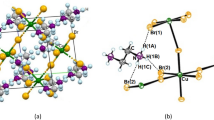

The room temperature crystal structure of zinc guanidine sulfate was described forty years ago by Morimoto and Lingafelter6 and confirmed later in14. Zn[C(NH2)3]2(SO4)2 crystallizes in tetragonal system, adopting \(\text{I}\overline{4}2\text{d }\) centrosymmetric space group. The asymmetric unit contains Zn at site 4, sulfate group with S at position 0.2. and a guanidinium counterion with 0.2. axis passing through carbon and nitrogen atoms. All remaining atoms occupy general positions. Zn atom is tetrahedrally coordinated by sulfate ions, forming Zn–O(2)–S–O(2)–Zn bridges between neighboring zinc ions, resulting in a 3-D inorganic framework. The large interstitial voids within the network are occupied by guanidinium ions that are additionally anchored via N–H⋯O hydrogen bonds14—Fig. 1.

The symmetry of the crystal structure lowers from \(\text{I}\overline{4}2\text{d }\) to \(\text{I}\overline{4 }\) in a continuous phase transition affecting both zinc-sulfate substructure and positions of counterions. The reduction in symmetry leads to an increase in the number of symmetry-independent atoms. In phase II, two independent Zn atoms lie on the \(\overline{4}\) axis, while all remaining atoms adopt general positions.

The structural distortions observed in phase II alter the shape of the voids. Symmetry mode analysis conducted in AMPLIMODES23 for all non-hydrogen atoms revealed that the structure of the low-temperature phase II exhibits two distortion modes: a primary one that yields \(\text{I}\overline{4 }\) symmetry and a secondary one compatible with the parent \(\text{I}\overline{4}2\text{d }\) structure. The mode decompositions indicate the main role of the primary distortion that involves 15 of the 27 structural degrees of freedom present in phase II (Hydrogen atoms were not taken into account). Total distortion amplitude, calculated as the square root of the sum of the square of all atomic displacements, is equal to 0.6883 Å, while the amplitude of the primary distortion is calculated at 0.664(7) Å. The maximum atomic displacement concerns oxygen O(1) atom which shifted by 0.212 Å to position O(11) and by 0.145 Å to position O(1) in phase II. In the GUA counterion the maximum displacements are observed for the nitrogen atom at N(2) position that shifted by 0.138 Å to position N(3) and 0.126 Å to position N(2) in the low-temperature phase.

Thermally activated displacements of GUA, which are evident in large displacement ellipsoids observed in phase I, are blocked below TC. This inhibition leads to a reduction in symmetry due to changes in the configuration of N–H⋯O hydrogen bonds, which are coupled with shifts of sulfate oxygen atoms and slight reorientations of GUA within the structure (see Fig. 2). The twofold axis passing through sulfate group, N(1) and central carbon atom of GUA vanish. Consequently, hydrogen bonds between NH2 groups and oxygen atoms slightly rearranged and new N(3)-H⋯O(2) bond is formed. Thus, polar displacements of GUA NH2 groups and the oxygen acceptors from inorganic substructure are the internal order parameter in GZS.

Crystal growing and samples

GZS crystals were obtained from aqueous solution with a stoichiometric ratio of guanidine sulfate {[C(NH2)3SO4} and zinc sulfate {ZnSO4·7H2O}, with a small addition of sulfuric acid {H2SO4} by the method of slow evaporation of solution at a constant temperature of 305 K. The possible impurities were eliminated through repeated recrystallization. Crystals without visible defects were used as seeds for further crystallization. Good-quality monocrystals with sizes of several cm3 were obtained within a few weeks.

Rectangular samples with perfectly parallel edges were cut from large GZS monocrystals, and their largest surfaces were perpendicular to the [100] and [001] directions. The size of the samples was 10.3 × 3.4 × 0.7 mm3. Vacuum-deposited gold electrodes were applied to the largest surfaces of the samples.

Linear expansion

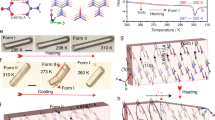

Thermal expansion was measured using a homemade capacitance quartz dilatometer. Crystal bars with a length of a few mm along the [100] and [001] crystallographic directions were used for measurement. The capacitance was measured using an HP LCR meter at a frequency of 1 kHz on a cooling run with a rate of 0.3 K/min. Temperature-dependent changes in the linear expansion of the GZS crystal, shown in Fig. 3, clearly indicate the presence of a second-order phase transition at 178 K.

The jump in the expansivity coefficient in the [100] direction, amounting to − 1.648 × 10–4, is significantly larger than in the [001] direction, which is + 0.743·10−4. Furthermore, for the [001] direction, a change in the expansivity coefficient sign occurs at a temperature of 182.2 K. The value of the expansivity coefficient in the [001] is comparable to the jump in triglycine sulfate (+ 2.4·10−4)24, and significantly greater than for Rb2ZnCl4 (+ 7.7·10−5)25. Presented above temperature-dependent changes in linear expansivity were utilized in the calculations of elastic stiffness coefficients and piezoelectric effect values.

Dielectric permittivity

Temperature-dependent changes in complex dielectric permittivity were measured in the frequency range from 100 Hz to 10 MHz using a precision impedance meter Hewlett-Packard HP4192A; the measurement field intensity was 1 V/mm. Temperature was changed at a rate of 0.5 K/min and measured with a chromel-CuFe thermocouple. In the samples cut in perpendicular to both [001] and [100] directions, a small anomaly in the real part of the dielectric permittivity was observed at 178 K—Figs. 4 and 5. In the frequency range used for the measurement, there was no dispersion in the real part of the dielectric permittivity. The imaginary part did not show anomalies at TC, and the dispersion observed in the high-temperature phase was due to sample conductivity, while the maximum ε″ for the [100] direction was caused by piezoelectric resonance—Fig. 4. This type of temperature dependence is typical of structural nonferroelectric second-order phase transitions described by a single order parameter26. Zinc sulfate guanidine crystallizes in a tetragonal system; therefore, the values of the real part of the dielectric permittivity are identical in the [100] and [010] directions. Dielectric permittivity was measured both on heating and cooling, and no temperature hysteresis was observed.

Piezoelectric and elastic constants

Piezoelectric and elastic properties were investigated using the resonance method27. Samples were placed in a homemade non-lossy holder and excited to face-shear and longitudinal vibrations using a computer-controlled impedance analyzer HP 4294A. The measurement field intensity was 1 V/mm, and the frequency was changed in the range from 50 kHz to 2 MHz with a step of 10 Hz.

Resonant frequencies (fr) and anti-resonant frequencies (fa) were used to determine the components of the tensors of the electromechanical coupling coefficient, elastic stiffness, and piezoelectric effect according to the following formulas27.

As the electromechanical coupling coefficient takes small values, it can be expressed by a simplified relation:

where i = 1,2,3 are directions of the electric field, j = 1÷6 are the shear stress indices in matrix notation;

- elastic stiffness coefficients for longitudinal modes:

and for shear modes:

where a and b are the width and length of the sample, respectively, m and n are small integers, crystal density ρ = 1935 kg/m3 7;

- components of the piezoelectric tensor:

where εi and ε0 denote the relative dielectric constant of the crystal and the dielectric constant of vacuum, respectively;

- vibration damping was determined from the relation:

where A(fr) and A(fa) are the values of the impedance at the resonant and antiresonant frequencies.

The point symmetry \(\overline{4}\)2m of the GZS crystal implies the presence of two independent piezoelectric components, d14 and d36, as well as two associated elastic stiffness components, c44 and c66, at room temperature. At 295 K, the measured values of these components are as follows: d14 = 1.89, d36 = 2.39 (in pm/V), c44 = 7.71, c66 = 6.30 (in GPa). The calculations were performed taking into account the changes in the sample dimensions due to thermal expansion. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the temperature dependencies of the aforementioned components and their corresponding resonant damping. Anomalies in these quantities at 178 K, i.e., maxima of the piezoelectric effect and damping, as well as abrupt changes in elastic stiffness, are characteristic of second order phase transitions.

In the low-temperature phase with point symmetry \(\overline{4}\), two additional independent piezoelectric components, d15 and d31, representing a macroscopic parameter of ferroelastoelectric ordering, should be observed. In this phase, domains with different signs of these components may exist. Monodomainization of the ferroelastoelectric state can only be achieved by simultaneous application of a strong electric field and mechanical stress in appropriate directions28. Since our experiment involves free resonant vibrations, stress cannot be applied. We expected that monodomainization was achieved by applying an electric field with an intensity of 100 V/mm, and deformation was induced by the temperature gradient upon rapid cooling at a rate of 10 K/min down to the temperature of liquid nitrogen.

At a temperature of 134.6 K, anomalies caused by the resonant frequency of 1.58 MHz were observed in the studies of complex dielectric susceptibility in the [100] direction. This frequency results from shear vibrations through the thickness of the sample corresponding to the spontaneous component d15 of the piezoelectric effect. Unfortunately, due to the splitting of this frequency, it was not possible to measure the temperature-dependent values of d15 components. However, the frequency of 585 kHz was identified as normal vibrations across the width, enabling the determination of the temperature changes in the c11 stiffness component and the spontaneous d31 piezoelectric component. These changes are presented in Fig. 8. The value of the c11 component decreases with temperature from 30.7 GPa at 110 K to 28.2 GPa near TC. In this temperature range, damping increases drastically from 0.5 to 14. Above TC, this frequency is not observed. The value of the electromechanical coefficient k31 was small and increased almost linearly from 1.7 to 1.9%. The calculated value of the spontaneous d31 component increased from 0.93 at 110 K to 1.1 just below TC.

Discussion

In ferroelastoelectric phase transitions, macroscopic order parameters are represented by one of the four piezoelectric coefficients: d, h, g, e. However, coefficients e and g do not satisfy the thermodynamic conditions of the experiment. On the other hand, the measured d31 component of the piezoelectric tensor, obtained using the resonance method, exhibits an almost linear temperature dependence in the ferroelastoelectric phase and a jump to zero at the transition temperature (TC). As the phase transition is of the second kind, this component cannot be a macroscopic order parameter. Only the piezoelectric coefficient h, which connects polarization P with mechanical strain η (Pi = hijηj)29, can act as an order parameter. Its value is calculated using the formula:

where βSP is the value of spontaneous dielectric impermittivity.

To obtain the temperature dependence of spontaneous dielectric impermittivity, the low-temperature impermittivity was subtracted from its high-temperature values interpolated to the ferroelastoelectric phase. The obtained result is presented in Fig. 9. The temperature dependence of the component calculated from equation (6) is shown in Fig. 10. In the range of 140 ÷ 170 K, its temperature dependence is proportional to (TC − T)α, where α = 0.50 ± 0.05.

The results of the temperature-dependent studies of dielectric permittivity, elastic stiffness, piezoelectric phenomenon, and change in the crystal structure have demonstrated that the low-temperature phase of guanidine zinc sulfate crystal exhibits ferroelastoelectric ordering.

Data availability

The results of our research will be available upon request sent to corresponding authors.

References

Stoletov, A. Ueber die Magnetisirungsfunction des weichen Eisens, insbesondere bei schwächeren Scheidungskräften. Ann. Phys. 222, 439–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.18722220706 (1872).

Valasek, J. Piezoelectric and allied phenomena in Rochelle salt. Phys. Rev. 15, 537–538. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.15.505 (1920).

Aizu, K. Second-order ferroic state shifts. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 34, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1143/JPSJ.34.121 (1973).

Newnham, R. E. & Cross, L. E. Symmetry of secondary ferroics. I. Mater. Res. Bull. 9, 927–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5408(74)90172-X (1974).

Newnham, R. E. & Cross, L. E. Symmetry of secondary ferroics. II. Mater. Res. Bull. 9, 1021–1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5408(74)90012-9 (1974).

Morimoto, C. N. & Lingafelter, E. C. The crystal structure of zinc guanidinium sulfate. Acta Crystallogr. B 26, 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0567740870002364 (1970).

Haussühl, S., Bohatý, L. & Grazel, U. Elastic, electrostrictive, electro-optic, and nonlinear optical properties of tetragonal zinc guanidinium sulfate, Zn[C(NH2)3]2(SO4)2. Z. Kristallogr. 167, 307–309. https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.1984.167.3-4.307 (1984).

Siva Shankar, V., Siddheswaran, R., Bharthasarathi, T. & Murugakoothan, P. Growth and characterization of new semiorganic nonlinear optical zinc guanidinium sulfate single crystal. J. Cryst. Growth 311, 2709–2713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2009.03.001 (2009).

Gruszka, K., Hrabański, R., Ozga, J. & Czapla, Z. EPR study of guanidine zinc sulphate crystals. Nukleonika 58, 387–390 (2013).

Antony, C. J., Bushiri, M. J., Varghese, H. T., Panicker, C. Y. & Fleck, M. Spectroscopic properties of guanidinium zinc sulphate [C(NH2)3]2Zn(SO4)2 and ab initio calculations of [C(NH2)3]2 and HC(NH2)3. Spectrochim. Acta A 73, 942–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2009.04.024 (2009).

Kapustianyk, V., Semak, S., Chornii, Y. & Rudko, M. Manifestation of ferroelastoelectric phase transition in temperature changes of the optical absorption edge in (NH4)2CuCl4·2H2O crystal. Phase Transit. 95, 626–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411594.2022.2088372 (2022).

Bohatý, L., Haussühl, S., Becker, P., Schmid-Rausch, K. & Stade, J. Z. Kristallogr. Suppl. 22, 57 (2005).

Czapla, Z., Komar, J., Marciniszyn, T. & Poprawski, R. Phase transition and anisotropic conductivity in guanidine zinc sulfate crystals. Solid State Ionics 196, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssi.2011.05.021 (2011).

Zdanowska-Frączek, M. et al. Structure, proton conductivity and molecular dynamice of guanidine zinc sulfate. Solid State Ionics 303, 113–118 (2017).

Mohler, E. & Pitka, R. Piezoelectric properties of NH4Cl near its order-disorder phase transition. Solid State Commun. 14, 791–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-1098(74)90887-4 (1974).

Akimov, S. V. et al. Twinning in paratellurite crystals. Ferroelectrics 359, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00150190701513043 (2007).

Browall, K. W., Kasper, J. S. & Wiedemeier, H. Single-crystal studies of β-Ag2HgI4. J. Solid State Chem. 10, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4596(74)90004-8 (1974).

Tylczyński, Z. & Wiesner, M. Ferroelastoelectric phase transition in (NH4)2CuCl4·2H2O single crystal. Mater. Chem. Phys. 149–150, 566–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2014.11.007 (2015).

Kapustianyk, V., Semak, S., Chornii, Y., Bovgyra, O. & Kovalenko, M. Manifestation of the ferroelastoelectric phase transition in the absorption spectra of (NH4)2CuCl4·2H2O crystals. Physica B 639, 413929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2022.413929 (2022).

Małuszyńska, H., Tylczyński, Z. & Cousson, A. Ferroelastoelectric ordering in (NH4)2CuBr4.2H2O single crystal. CrystEngCom 15, 7498–7504. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ce41113c (2013).

Tylczyński, Z., Wiesner, M. & Trzaskowska, A. Spontaneous piezoelectric effect as order parameter in (NH4)2CuBr 4.2H2O crystal. Physica B 500, 85–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2016.07.014 (2016).

Nye, J. F. Physical Properties of Crystals: Their Representation by Tensor and Matrices (Clarendon Press, 1985).

Orobengoa, D., Capillas, C., Aroyo, M. I. & Perez-Mato, J. M. AMPLIMODES: Symmetry-mode analysis on the Bilbao crystallographic server. J. Appl. Cryst. A 42, 820–833. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889809028064 (2009).

Deguchi, K. Critical behaviour in thermal expansion coefficient and dielectric constant of triglycine sulfate. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 47, 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1143/JPSJ.47.153 (1979).

Jamaguchi, T. & Shimizu, F. Thermal expansion of ferroelectric Rb2ZnCl4. Ferroelectrics 237, 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00150190008216250 (2000).

Strukov, B. A. & Levanyuk, A. P. Ferroelectric Phenomena in Crystals (Springer, Berlin, 1988).

Mason, W. P. Piezoelectric Crystals and Their Applications to Ultrasonics (Van Nostrand Company, 1950).

Vadhawan, V. K. Ferroelasticity and related properties of crystals. Phase Transit. 3, 3–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411598208241323 (1982).

Slonczewski, C. & Thomas, H. Interaction of elastic strain with the structural transition of strontium titanate. Phys. Rev. B 1, 3599–3608. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.1.3599 (1970).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZT: samples preparation, results analysis, manuscript preparation MW: dielectric and piezoelectric measurements ZC: crystal growth, thermal expansion experiments AG: structural analysis

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tylczyński, Z., Wiesner, M., Czapla, Z. et al. Spontaneous piezoeletric effect as evidence of ferroelastoelectricity in guanidine zinc sulfate crystal. Sci Rep 14, 18020 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67612-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67612-7