Abstract

In recent decades, the atmospheric moisture capacity has increased globally in concert with global warming, with a particularly notable warming trend in Arctic regions. However, due to limited observational data, the variation and causes of polar precipitation, especially large-scale precipitation events associated with Arctic cyclones, remain unclear. In this paper, GPM satellite data are compared with ERA5 reanalysis data to explore the characteristics of summer precipitation at the northern margin of the Eurasian region (NMER) and the influence of cyclone activity on precipitation. It is revealed that high precipitation values in the Arctic region, as indicated by the GPM and ERA5 data, are mainly concentrated at the NMER. However, the GPM data show an overall larger precipitation amount, while the station observations more closely agree with the ERA5 precipitation changes at the NMER. The cyclone identification results indicate that summer cyclones at the NMER are mainly distributed in the Barents, Kara and Laptev Seas, and the precipitation contribution rate of ERA5-derived cyclones is 37.35%, which is significantly higher than that of GPM-derived cyclones (29.47%). Furthermore, high cyclone activity results in more intense precipitation, with the top 5% of the strongest cyclones contributing 60% (GPM) and 40% (ERA5) to the total cyclonic precipitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The activity of Arctic cyclones plays a vital role in transporting energy, momentum, and moisture from mid- to high-latitude areas to polar regions1, thereby connecting Arctic climate dynamics with those at middle to low latitudes. Arctic cyclones are classified into two types based on their generation: immigrant cyclones, which originate from mid-latitude temperate cyclones and move poleward into the Arctic region, and locally generated cyclones within the Arctic region2. In recent decades, against the background of global warming, the decrease in Arctic sea-ice has increased3,4, creating conditions favorable for accessing abundant natural resources through Arctic shipping routes (Arctic routes)5,6. However, the severe weather conditions associated with cyclonic activity, including strong winds and heavy precipitation, pose significant threats to the sustainable development of Arctic routes, especially in the case of intense Arctic cyclones7,8,9,10.

Cyclonic activity readily triggers widespread heavy precipitation, which plays a vital role in regulating local water vapor, and precipitation associated with cyclonic activity often explained more than 70% of the total precipitation11. Previous studies have indicated that cyclones can significantly influence the formation and evolution of upper-level cloud systems near cyclone centers by altering the distributions of the atmospheric temperature, humidity, and wind direction2,12. Recent amplified warming in the Arctic region4,13 has led to an increase in the atmospheric moisture-holding capacity. With the use of JRA-25 reanalysis data, Stroeve et al.14 reported an increase in precipitation associated with autumn Arctic cyclones. They attributed this phenomenon to the higher atmospheric humidity and increased water vapor content in recent years, leading to an increase in the precipitation efficiency of cyclones as a primary reason for the increased precipitation associated with cyclones.

Previous research has focused on the impact of extratropical cyclone activity on precipitation in mid- and high- latitudes regions using various reanalysis datasets and global climate models/regional climate models (GCMs/RCMs)11,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. However, when focusing on the entire extratropical latitudes of Northern Hemisphere, the precipitation in the Arctic (> 70° N) was quite poor, and their analysis mainly emphasized on the highest precipitation regions (Atlantic and Pacific Oceans). Furthermore, due to the scarcity of long-term precipitation observations in the Arctic region, relatively few studies have focused on evaluating cyclone-related precipitation in the Arctic using satellite observational data. The GPM precipitation data is one of the few satellite observation datasets currently available for the entire Arctic region, which is the largest difference between ERA5 and GPM. Although some previous studies have used ERA5 reanalysis dataset to study the precipitation associated with cyclone activity11,20, the reanalysis data are not directly derived from satellite observations. With the development of satellite observation technology in recent decades, it has become necessary to compare the differences between reanalysis dataset and satellite observations, especially in the Arctic region, where there are fewer observations. Meanwhile, GPM precipitation data also have a higher horizontal resolution (0.1° × 0.1°) compared to the scarce ground-based observations in the Arctic. Therefore, further clarification is needed of the contribution of Arctic cyclone activity to local precipitation and of the differences between satellite observational data and reanalysis data. Moreover, the area along the northern margin of the Eurasian region (NMER) starting from the Barents Sea is a critical region for sea–ice–atmosphere coupling21. It is also the northeastern branch of the Arctic routes. The rapid melting of sea ice in this region due to global warming raises the question of whether it can impact local precipitation changes and is closely linked to the sustainable development of Arctic routes. Therefore, in this study, GPM satellite precipitation data and ERA5 reanalysis data are utilized to assess the consistency of cyclone-related precipitation at the northern margin of the Eurasian continent during the summer season. The aim of this research is to analyze the contribution of Arctic cyclone activity to the overall local precipitation in this region.

Data and methods

Data

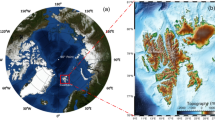

The data used in this study include the following: (1) the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) satellite precipitation dataset was generated by a satellite observation program conducted jointly by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)22. We used the GPM Level-3 Final Merged Precipitation product (GPM_3IMERGHH), which covers the 2015 to 2021 period after stable satellite operation and exhibits a half-hourly temporal resolution and a spatial resolution of 0.1° × 0.1°. (2) Gridded precipitation data were obtained from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) reanalysis dataset, specifically the ERA5 dataset23. This product provides hourly estimates of atmospheric, land, and ocean meteorological elements globally, with a spatial resolution of up to 0.25° × 0.25°. (3) Station-based observed precipitation data were obtained from the Global Historical Climatology Network Daily (GHCN-Daily), which provide daily precipitation data for individual stations24. Due to complete absence of precipitation data at some stations and cessation of data updating at others, seventeen observation stations were selected along the NMER, as shown in Fig. 2a.

Methods: cyclone identification and tracking

We employed the cyclone identification algorithm based on the mask region-based convolutional neural network (Mask R-CNN) model proposed by Lu et al.25. The algorithm was applied to identify Arctic cyclones (north of 60° N) based on the sea level pressure (SLP) in the ERA5 reanalysis data at 6-h intervals. The Mask R-CNN model proposed by He et al.26 has been widely used for various tasks involving the identification of object shapes25,27,28. Lu et al.25 applied it to identify extratropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere, demonstrating good performance in delineating the outer contours and locating the center points of cyclones. A nearest neighbor criterion based on the distance of cyclone center across adjacent time steps is used to track cyclone paths29,30. Specifically, to further identify the path corresponding to each cyclone, it is determined whether there is a cyclone at the next time step within a 500 km radius of the cyclone center at the current time step. If so, it is considered the same cyclone and the process is repeated until no cyclone is found within the radius threshold. This approach facilitates the determination of a dataset containing the pathways corresponding to each cyclone, along with the associated sea level pressure (SLP) at cyclone centers. The intensity of cyclone is determined based on the SLP value of cyclone center and the lifetime of each cyclone can be confirmed by the total duration of its activity track. The frequency of cyclones indicates the proportion of time that cyclones occurred relative to the total time during the entire study period.

The definition of cyclone-related precipitation

To statistically account for the impact of cyclones on precipitation, we calculated the cyclone-related precipitation. Specifically, first of all, half-hourly satellite precipitation data and hourly reanalysis precipitation data are processed to obtain 6-h cumulative precipitation data respectively. Then, these two kinds of precipitation data are interpolated to a T255 Gaussian grid (the spatial resolution of the extratropical cyclone dataset). Subsequently, the precipitation within the outmost profile of each cyclone is defined as cyclone-related precipitation.

Results

Climatic characteristics of summer precipitation in the arctic

Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of the summer (JJA) daily precipitation for the multiyear average from 2015 to 2021 using the GPM and ERA5 data. As shown in Fig. 1a, GPM precipitation at high latitudes is predominantly concentrated in the northern Atlantic and NMER, including the Barents Sea, Kara Sea, and Laptev Sea, and extends southward to the northern side of the Taymyr Peninsula and the Central Siberian Plateau. The maximum precipitation occurs in the northern Atlantic and on the northern side of the Eurasian continent, reaching values exceeding 3 mm/day. Additionally, there is significant precipitation near 70° N in the Western Hemisphere, likely associated with cyclonic activity moving from mid-latitudes toward the Arctic and carrying substantial moisture31,32.

Climate mean of daily accumulated precipitation (unit: mm/day) during the summer seasons (JJA) from 2015 to 2021. Data sourced from (a) GPM precipitation data and (b) ERA5 precipitation data. The black box outlines the northern margin of the Eurasian region (NMER), spanning from 70° N to 80° N and 30° E to 150° E.

The distribution of ERA5 precipitation closely resembles that of GPM precipitation in the Eastern Hemisphere (Fig. 1b), with the maximum precipitation occurring in the northern Atlantic and on the northern side of the Eurasian continent. There is also precipitation along the NMER near the Barents Sea, Kara Sea, and Laptev Sea. In the North Pacific, the precipitation in the ERA5 data is less than that in the GPM data, and there is a pronounced precipitation maximum west of Greenland. Differences between the two datasets are evident around Greenland and the Arctic center. Overall, GPM precipitation at high latitudes is generally higher than ERA5 precipitation apart from Greenland and the vicinity of the Arctic center. Specifically, in the regions of the northern Atlantic and the NMER (70° N–80° N, 0° E–180° E), the daily average total precipitation is 1.71 mm/day in the GPM data compared to 1.44 mm/day in the ERA5 data. It is important to note that summer precipitation in the central Arctic and Greenland is considerably lower than that in the other regions, and GPM precipitation is notably underestimated compared to ERA5 precipitation. This difference is primarily due to limitations in the detection capabilities of the AMSR under cold and sea ice conditions, which affects the accuracy and availability of precipitation estimates and leads to frequent data gaps33.

Based on the spatial distribution characteristics of precipitation at high latitudes determined by the GPM and ERA5 data, the NMER (70° N–80° N, 30° E–150° E) is identified as the primary region with high precipitation values. Therefore, the reliability of the GPM and ERA5 precipitation data in this area was evaluated using GHCN-Daily station data. The map displays the specific locations of station data (Fig. 2a).

(a) The spatial distribution of 17 GHCN-Daily stations, (b) along with their correlation coefficients and root mean square errors (RMSE) in relation to daily accumulated precipitation from GPM and ERA5. In Figure (a), the black numbers represent the average daily precipitation at the stations, while the red numbers correspond to the Station Index in Figure (b). In Figure (b), yellow (blue) bars represent the correlation coefficients between precipitation at GHCN-Daily stations and GPM (ERA5) precipitation, while red (black) solid lines indicate the root mean square errors (RMSE) between GHCN-Daily station precipitation and GPM (ERA5).

For quantitative comparison of the consistency between the station data and the data from these two sources, the daily precipitation from the GPM and ERA5 data in the vicinity of each station was calculated (the average precipitation from the nine grid points nearest to a specific station, representing the precipitation at that station). The correlation coefficient and root mean square error (RMSE) between the station and GPM/ERA5 precipitation values were calculated to measure the linear relationship between the grid data products and the meteorological station observation data, as well as the overall deviation in the errors of the grid data products. Based on the climatology of the daily precipitation at these stations, the summer average station precipitation suitably agrees with both the GPM and ERA5 precipitation data. Figure 2b clearly shows that the correlation between the ERA5 precipitation and station precipitation is higher. At more than 70% (12/17) of the stations, the correlation coefficient with ERA5 precipitation is greater than 0.5, and the RMSEs between the station precipitation and ERA5 precipitation are all much lower than those with GPM precipitation. Table S1 provides the correlation coefficient values with the GPM and ERA5 precipitation data at these 17 stations (see Supplementary). The correlation coefficients all passed the 99% confidence level t test, indicating that, compared to the GPM precipitation data, the station precipitation at the NMER corresponds more closely to the ERA5 precipitation data.

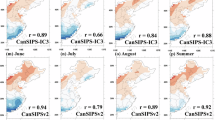

Arctic cyclone-related precipitation

Previous studies have emphasized that extratropical cyclones are crucial for triggering precipitation11,14,17,19. To investigate the contribution of Arctic cyclone activity to summer precipitation at the NMER, the Mask R-CNN cyclone identification algorithm proposed by Lu et al.25 was utilized to identify Arctic cyclones in the sea level pressure (SLP) of the ERA5 data. Additionally, conventional grids become blurred near the polar regions, thus the identified cyclones are re-gridded spatially onto a 100 km × 100 km equal-area grid. The summer distribution of Arctic cyclones is shown in Fig. 3. The percentage of summer cyclone occurrence frequency in Fig. 3b indicates the proportion of time that cyclones occurred relative to the total time during the entire study period. Figure 3a and b show that the high-frequency zone of summer Arctic cyclones at the NMER is mainly concentrated in the northern seas of Eurasia. The high-frequency zone is located in the northeastern parts of the Kara Sea and Barents Sea, with cyclone occurrence frequencies exceeding 20%. The next notable regions are the Laptev Sea and the Arctic Ocean to the north. In contrast, the number of cyclones over land is relatively small. This distribution is generally consistent with the localized distribution characteristics of summer cyclones near the northern edge of the Eurasian continent reported by Simmonds et al.34 and Zahn et al.35.

Figure 4 shows additional statistics of the precipitation associated with Arctic cyclone activity. As shown in Fig. 4a, according to the GPM precipitation dataset, cyclone-related precipitation is mainly concentrated over the Taymyr Peninsula, the Barents Sea, the Kara Sea, and the Laptev Sea. The highest cyclone-related precipitation occurs in the Kara Sea, reaching up to 1.2 mm/day. In contrast, cyclone-related precipitation over the Arctic Ocean north of the Laptev Sea is lower. The ERA5 results (Fig. 4b) generally match the distribution of cyclone-related precipitation from the GPM data, except for the region from 90 to 120°E over the continent. However, the precipitation associated with cyclones was lower in the ERA5 data, with the highest values exceeding 0.8 mm/day in the Kara Sea. Additionally, the cyclone-related precipitation in the GPM data was lower over the Arctic Ocean north of the Laptev Sea than that in the ERA5 data.

To elucidate the significance of cyclone-related precipitation processes for the total precipitation, Fig. 5 shows the contribution of summer cyclone-related precipitation to the total precipitation at the NMER. Specifically, the numerator represents the total accumulated cyclone-related precipitation at each grid point, while the denominator represents the total precipitation at the corresponding grid point. As shown in Fig. 5a, the maximum contribution of cyclone-related precipitation in the GPM data was located over the Kara Sea and the Taymyr Peninsula, reaching more than 40%, and the contribution of cyclone-related precipitation along the entire NMER was 29%. In the ERA5 precipitation data (Fig. 5b), the high-contribution zone was concentrated over the Kara Sea, exceeding 50%. The second-highest contribution area was located northeast of the Barents Sea and over the Arctic Ocean north of the Laptev Sea. Overall, the contribution of cyclone-related precipitation in the ERA5 data was significantly greater than that in the GPM data, with a regional average difference of 7.88%. Differences in the contributions of cyclone-related precipitation between the two datasets were mainly observed in the Laptev Sea and the region north of 75°N. This may be related to the limitations in the ability of the GPM to retrieve precipitation in high-latitude regions33.

In recent decades, with the rapid reduction in Arctic sea-ice, high cyclonic activity has been frequently observed in the Arctic region in summer8,9,10. To investigate the relationship between the cyclone intensity and cyclone-related precipitation, a statistical analysis of the distribution function of cyclone-related precipitation with respect to the cyclone intensity was conducted (Fig. 6). Particularly, max intensity on the horizontal axis refers to the lowest sea level pressure (SLP) value of each cyclone, sorted across all cyclone and presented as percentiles. And the precipitation contribution on the vertical axis refers to the proportion of the accumulated cyclone-related precipitation along its track of each cyclone, relative to the total accumulated cyclone-related precipitation of all cyclone across their paths during the study period. Combined with the analysis of each complete cyclone path identified by the algorithm, it is found that high summertime cyclonic activity at the NMER contributes a high percentage to the total cyclone-related precipitation over their lifecycle. This feature is evident in both the GPM and ERA5 precipitation data. Specifically, the top 5% of the strongest cyclones contributed 60% to the total cyclone-related precipitation in the GPM data and 40% in the ERA5 data. In contrast, the subsequent 20% of weaker cyclones contributed less than 2% to the total cyclone-related precipitation. This indicates that high cyclonic activity could cause larger precipitation amounts, while low cyclonic activity could only lead to a small amount of precipitation. These findings are broadly consistent with the conclusions drawn by Hawcroft et al.11, who analyzed the connection between GPCP precipitation and ERA-Interim reanalysis precipitation data and extratropical cyclone activity for the 1996–2009 period at mid-high latitudes. Akperov & Mokhov20 also obtained the similar conclusion that the intense cyclone was associated with more precipitation based only on ERA5 reanalysis data. In addition, Messmer and Simmonds36 considered the relationship between extreme events (precipitation or wind) and cyclone using two cyclone tracking algorithms, but the emphasis on summer cyclones and associated extreme precipitation in their paper remained primarily in the tropics and midlatitude regions (Atlantic and Pacific) of the Northern Hemisphere.

The distribution of cyclones of varying intensities in the northern margin of the Eurasian region (NMER) (70° N–80° N, 30° E–150° E) during the summer season (JJA) and their contributions to cyclone-related precipitation are depicted. The blue line (red line) represents precipitation data from GPM (ERA5).

Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, the differences in precipitation between GPM satellite data and ERA5 reanalysis data in the Arctic region are investigated, with a specific focus on exploring the contribution of cyclonic activity to the total precipitation in summer at northern edge of the Eurasian continent. The key findings are as follows:

-

(1)

Precipitation in the Arctic is characterized by a meridional gradient, with higher precipitation levels on the continental side and lower precipitation levels over the Arctic Ocean. And the high-precipitation zone identified by the GPM data is concentrated in a narrow latitudinal band stretching from the North Atlantic to the northern edge of the Eurasian continent. The ERA5 precipitation data are similar to the GPM precipitation data at the NMER. However, the ERA5 data indicate a lower total precipitation in the Arctic region than the GPM data. The station precipitation data for the NMER agree better with the ERA5 precipitation data than with the GPM precipitation data, indicating greater reliability.

-

(2)

High-frequency cyclones occur mainly over the northern seas of the Eurasian continent, while the number of cyclones over land is relatively small. The cyclone-related precipitation from the GPM data is lower over the Arctic Ocean north of the Laptev Sea than that from the ERA5 data. Furthermore, the contribution of cyclonic precipitation to the total precipitation in the GPM data is generally lower than that in the ERA5 data along the entire NMER.

-

(3)

High summer cyclonic activity at the NMER contributes a higher percentage to the total cyclonic-related precipitation over its lifecycle, as reflected in both the GPM and ERA5 precipitation data. Specifically, the top 5% of the strongest cyclones contribute 60% and 40% to the total cyclonic precipitation in the GPM and ERA5 data, respectively. This indicates that high cyclonic activity could result in higher-intensity Arctic precipitation, particularly according to the GPM data.

Several case studies on individual strong Arctic cyclones have indicated that their structure is influenced not only by low-level baroclinicity but also by the activity of lower-tropospheric potential vortices37,38,39. Exploring the thermodynamic structures of Arctic cyclones and their impact on the precipitation intensity is crucial for predicting the activity of strong Arctic cyclones and issuing disaster warnings for Arctic routes. Therefore, further clarification is needed of the influence of lower-tropospheric potential vortices on the intensity of Arctic cyclones and cyclone-related precipitation.

Data availability

GPM V06 half-hourly 0.1° × 0.1° satellite precipitation data was freely downloaded from https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/GPM_3IMERGHH_06/summary?keywords=GPM%20IMERG%20final accessed on December 6, 2022. And the cyclone label dataset is provided by Yang Kong. The reanalysis is based on the concurrent ERA dataset provided by ECMWF, which can be accessed at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=form, with the access date being October 25, 2023. GHCN-Daily station daily precipitation data is sourced from https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cdo-web/datasets, accessed on November 9, 2023.

References

Ulbrich, U., Leckebusch, G. C. & Pinto, J. G. Extra-tropical cyclones in the present and future climate: A review. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 96, 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-008-0083-8 (2009).

Zhang, X., Walsh, J. E., Zhang, J., Bhatt, U. S. & Ikeda, M. Climatology and interannual variability of arctic cyclone activity: 1948–2002. J. Clim. 17, 2300–2317. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017%3c2300:Caivoa%3e2.0.Co;2 (2004).

Comiso, J. C. & Hall, D. K. Climate trends in the Arctic as observed from space. WIREs Clim. Change 5, 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.277 (2014).

Serreze, M. C. & Barry, R. G. Processes and impacts of Arctic amplification: A research synthesis. Glob. Planet. Change 77, 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2011.03.004 (2011).

Stephenson, S. R., Smith, L. C., Brigham, L. W. & Agnew, J. A. Projected 21st-century changes to Arctic marine access. Clim. Change 118, 885–899. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0685-0 (2013).

Theocharis, D., Pettit, S., Rodrigues, V. S. & Haider, J. Arctic shipping: A systematic literature review of comparative studies. J. Transp. Geogr. 69, 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.04.010 (2018).

Peng, L. et al. Role of intense arctic storm in accelerating summer sea ice melt: An in situ observational study. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021gl092714 (2021).

Simmonds, I. & Rudeva, I. The great Arctic cyclone of August 2012. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012gl054259 (2012).

Vüllers, J. et al. Meteorological and cloud conditions during the Arctic Ocean 2018 expedition. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 289–314. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-289-2021 (2021).

Zhang, J., Lindsay, R., Schweiger, A. & Steele, M. The impact of an intense summer cyclone on 2012 Arctic sea ice retreat. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 720–726. https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50190 (2013).

Hawcroft, M. K., Shaffrey, L. C., Hodges, K. I. & Dacre, H. F. How much Northern Hemisphere precipitation is associated with extratropical cyclones?. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012gl053866 (2012).

Simmonds, I. & Keay, K. Extraordinary september arctic sea ice reductions and their relationships with storm behavior over 1979–2008. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009gl039810 (2009).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334–1337. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09051 (2010).

Stroeve, J. C., Serreze, M. C., Barrett, A. & Kindig, D. N. Attribution of recent changes in autumn cyclone associated precipitation in the Arctic. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0870.2011.00515.x (2011).

Finnis, J., Holland, M. M., Serreze, M. C. & Cassano, J. J. Response of Northern Hemisphere extratropical cyclone activity and associated precipitation to climate change, as represented by the community climate system model. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jg000286 (2007).

Hawcroft, M. K., Shaffrey, L. C., Hodges, K. I. & Dacre, H. F. Can climate models represent the precipitation associated with extratropical cyclones?. Clim. Dyn. 47, 679–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-015-2863-z (2015).

Kodama, C., Stevens, B., Mauritsen, T., Seiki, T. & Satoh, M. A new perspective for future precipitation change from intense extratropical cyclones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 12435–12444. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019gl084001 (2019).

Wernli, H. & Pfahl, S. Quantifying the relevance of cyclones for precipitation extremes. J. Clim. 25, 6770–6780. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-11-00705.1 (2012).

Zhang, Z. & Colle, B. A. Changes in extratropical cyclone precipitation and associated processes during the twenty-first century over Eastern North America and the Western Atlantic using a cyclone-relative approach. J. Clim. 30, 8633–8656. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-16-0906.1 (2017).

Akperov, M. G. & Mokhov, I. I. Changes in cyclone activity and precipitation in the extratropical latitudes of the northern hemisphere in recent decades according to ERA5 reanalysis. Atmos. Ocean. Opt. 36, 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1134/s1024856023050020 (2023).

Smedsrud, L. H. et al. The role of the barents sea in the arctic climate system. Rev. Geophys. 51, 415–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/rog.20017 (2013).

Hou, A. Y. et al. The global precipitation measurement mission. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 95, 701–722. https://doi.org/10.1175/bams-d-13-00164.1 (2014).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorolog. Soc. 146, 1999–2049. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803 (2020).

Houston, T. G., Gleason, B. E., Vose, R. S., Durre, I. & Menne, M. J. An overview of the global historical climatology network-daily database. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 29, 897–910. https://doi.org/10.1175/jtech-d-11-00103.1 (2012).

Lu, C., Kong, Y. & Guan, Z. A mask R-CNN model for reidentifying extratropical cyclones based on quasi-supervised thought. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71831-z (2020).

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollar, P. & Girshick, R. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2980–2988 (2017).

Wu, W. et al. Improved mask R-CNN-based cloud masking method for remote sensing images. Int. J. Remote Sens. 41, 8910–8933. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2020.1792576 (2020).

Zhang, W., Witharana, C., Liljedahl, A. & Kanevskiy, M. deep convolutional neural networks for automated characterization of arctic ice-wedge polygons in very high spatial resolution aerial imagery. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10091487 (2018).

Kong, Y., Lu, C., Guan, Z. & Chen, X. Comparison of intense summer arctic cyclones between the marginal ice zone and central arctic. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023jd039620 (2024).

Lu, C. A modified algorithm for identifying and tracking extratropical cyclones. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 34, 909–924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-017-6231-2 (2017).

Dufour, A., Zolina, O. & Gulev, S. K. Atmospheric moisture transport to the arctic: assessment of reanalyses and analysis of transport components. J. Clim. 29, 5061–5081. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-15-0559.1 (2016).

Sorteberg, A. & Walsh, J. E. Seasonal cyclone variability at 70°N and its impact on moisture transport into the Arctic. Tellus A 60, 570–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0870.2008.00314.x (2008).

Huffman, G. J., Bolvin, D. T., Nelkin, E. J. & Tan, J. Integrated Multi-satellite Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) technical documentation. Nasa/Gsfc Code 612(47), 2019 (2015).

Simmonds, I., Burke, C. & Keay, K. Arctic climate change as manifest in cyclone behavior. J. Clim. 21, 5777–5796. https://doi.org/10.1175/2008jcli2366.1 (2008).

Zahn, M., Akperov, M., Rinke, A., Feser, F. & Mokhov, I. I. Trends of cyclone characteristics in the arctic and their patterns from different reanalysis data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 2737–2751. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017jd027439 (2018).

Messmer, M. & Simmonds, I. Global analysis of cyclone-induced compound precipitation and wind extreme events. Weather Clim. Extremes 32, ARTN100324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2021.100324 (2021).

Aizawa, T. & Tanaka, H. L. Axisymmetric structure of the long lasting summer Arctic cyclones. Polar Sci. 10, 192–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2016.02.002 (2016).

Gray, S. L., Hodges, K. I., Vautrey, J. L. & Methven, J. The role of tropopause polar vortices in the intensification of summer Arctic cyclones. Weather Clim. Dyn. 2, 1303–1324. https://doi.org/10.5194/wcd-2-1303-2021 (2021).

Tao, W., Zhang, J. & Zhang, X. The role of stratosphere vortex downward intrusion in a long-lasting late-summer Arctic storm. Q. J. R. Meteorolog. Soc. 143, 1953–1966. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3055 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge NASA and ECMWF for their effort in making the data available.

Funding

Jiangsu Provincial Key R&D Program (Grant No. BE2022161); Special Program for Innovation and Development of China Meteorological Administration (Grant No. CXFZ2022J031); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42274215); "Qing Lan" project of Jiangsu Province, and "333" project of Jiangsu Province for L.G. Ding; Wuxi University Research Start-up Fund for Introduced Talents (Grant No. 2023r037).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study. C.L. was responsible for conceptualization and methodology. Y. B. conducted the data acquisition and analysis. L. L. carried out revision and review of the manuscript. Y. K. assisted in writing the original draft. X. C. participated in the partial result analysis. All participants completed the final manuscript together.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, C., Bai, Y., Liu, L. et al. Role of cyclone activity in summer precipitation over the northern margin of Eurasia. Sci Rep 14, 16952 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67661-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67661-y