Abstract

Senescent cells have been linked to the pathogenesis of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). However, the effectiveness of senolytic drugs in reducing liver damage in mice with MASLD is not clear. Additionally, MASLD has been reported to adversely affect male reproductive function. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the protective effect of senolytic drugs on liver damage and fertility in male mice with MASLD. Three-month-old male mice were fed a standard diet (SD) or a choline-deficient western diet (WD) until 9 months of age. At 6 months of age mice were randomized within dietary treatment groups into senolytic (dasatinib + quercetin [D + Q]; fisetin [FIS]) or vehicle control treatment groups. We found that mice fed choline-deficient WD had liver damage characteristic of MASLD, with increased liver size, triglycerides accumulation, fibrosis, along increased liver cellular senescence and liver and systemic inflammation. Senolytics were not able to reduce liver damage, senescence and systemic inflammation, suggesting limited efficacy in controlling WD-induced liver damage. Sperm quality and fertility remained unchanged in mice developing MASLD or receiving senolytics. Our data suggest that liver damage and senescence in mice developing MASLD is not reversible by the use of senolytics. Additionally, neither MASLD nor senolytics affected fertility in male mice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

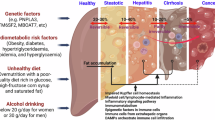

MASLD is a common liver disease characterized by triglycerides accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis1. MASLD is associated with type 2 diabetes (DM2), dyslipidemia and metabolic syndrome2. However, consumption of diets rich in cholesterol, saturated fats, and carbohydrates, as in the typical western diet (WD), are risk factors for MASLD independent of obesity3. The WD style is characterized by a high intake of processed foods, rich in animal proteins, simple carbohydrates, trans and saturated fats, and low in dietary fibers and unsaturated fatty acids4. Long-term chronic consumption of a WD contributes to development of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), which can progress to steatohepatitis5. In mice, consumption of a choline-deficient WD can lead to MASLD development without obesity6.

Evidence suggests that MASLD is associated to increased liver inflammation and senescent cell burden7. Senescence is a cellular state characterized by an irreversible cell cycle arrest triggered by cellular damage and aging8. Senescent cells produce and release a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), consisting of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, growth factors, proteases, and angiogenic factors9. The presence of SASP-producing senescent cells can induce chronic inflammation, leading to tissue dysfunction in older individuals10. Senescent cells can be cleared from different tissues by senolytic drugs11. Among these, dasatinib and quercetin (D + Q) and fisetin, can selectively eliminate senescent cells from various tissues, reducing circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and increasing longevity in mice12,13. Senescence also seems to be involved in the pathogenesis of MASLD. Treatment with D + Q has been shown to reduce hepatic lipid accumulation in mouse models of hepatic steatosis7. However, others shown that D + Q was not effective in removing senescent hepatocytes, worsening progression of liver disease and increasing hepatic damage and tumorigenesis14. Similarly, treatment with D + Q did not prevent in vitro doxorubicin induced senescence in liver cells15. Therefore, it is still not clear how MASLD can affect senescent cells accumulation in liver and the effectiveness of senolytics in this scenario.

In this context, MASLD may have a negative impact on male fertility. Men diagnosed with MASLD have reduced sperm quality and reproductive hormones16. MASLD is associated to low testosterone levels even after adjusting for the effects of adiposity and insulin resistance17. Obese rats with hepatic steatosis also had decreased sperm count and testosterone levels, which were reversed by omega-3 fatty acids treatment18. However, obese mice that did not develop hepatic steatosis also had decreased sperm count19. Overall, MASLD is associated to increased systemic inflammation20,21, which is an independent risk for reduced sperm count and decreased testosterone levels22. Therefore, is important to better understand the molecular mechanisms linking the effect of MASLD independent of obesity on male mouse fertility. Our previous studies suggest that D + Q can increase serum levels of testosterone and sperm concentration but not fertility in male mice under standard chow23. Therefore, our aim in the current study was to evaluate the protective effect of senolytic drugs (D + Q and fisetin) on liver damage and fertility of male mice with MASLD.

Results

Choline-deficient-WD induced MASLD that was not reverted by senolytics

Male mice were fed with a choline-deficient WD for 3-months to induce MASLD24. At 6 months of age mice were randomized within dietary treatment groups to receive dasatinib + quercetin (D + Q)7, fisetin (FIS)13 or vehicle control until 9 months of age (Fig. 1). Mice fed with choline-deficient WD developed liver changes indicating development of MASLD. The choline-deficient WD mice had increased liver mass (Fig. 2A), liver triglycerides (Fig. 2B), serum ALT and AST (Fig. 2C,D), liver fibrosis (Fig. 2E) and senescence (Fig. 2F). The NAFLD Activity Score was above 5 in choline-deficient WD fed mice, indicating the development of steatohepatitis (Suppl. Fig. 1)25. However, treatment with senolytic drugs was not able to reduce any parameters of liver damage in mice developing MASLD.

Experimental design. Mice were assigned to a standard or Western diet for the first 3 months of the study. After that mice were assigned to a control group (CTL), dasatinib and quercetin (D + Q) and fisetin (FISE) groups for 3 months. Six mice from each group were euthanized at 3 and 6 months of age. The remaining mice were bred with young control females for a period of 8 days.

Liver mass (A), liver triglycerides (B), serum ALT (C) and AST (D), liver fibrosis (PSR; E), liver senescence (F), representative histological images stained with picrosirius red (G–L) and lipofuscin staining (M–R) in male mice fed with standard diet (SD) or western diet (WD) and treated with placebo (CTL), dasatinib and quercetin (D + Q) and fisetin (FIS). The dotted line represents measures in 3-month-old control male mice. Representative images are presented at × 400 magnification. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Different letters indicate statistical difference at P < 0.05 between individual groups when a significant interaction effect was observed.

The body mass was lower in mice induced to MASLD, and no effect of senolytic drugs was observed (Fig. 3A,B). Calorie intake corrected for body mass was similar among groups during the first 3 months of experiment (Fig. 3C). However, in the last 3 months, calorie intake corrected for body mass decreased in the groups induced to MASLD, without any effects of senolytic drugs (Fig. 3D).

Body mass (A), body mass gain (B), calorie intake from 3 to 6 months of age (C), calorie intake from 6 to 9 months of age (D) in male mice fed with standard diet (SD) or western diet (WD) and treated with placebo (CTL), dasatinib and quercetin (D + Q) or fisetin (FISE). All data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Different letters indicate statistical difference at P < 0.05 between individual groups when a significant interaction effect was observed.

Liver expression of genes related to inflammation/senescence was not reversed by senolytics

Mice developing MASLD had increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL1-a, F4/80, Tnfa, IL6, IL1b) and senescence genes (LamnB1, Cdkn1a, Cdkn2a), as well as genes involved in fibrosis (Serpin E1, Col41a, Col14a1) and immune cell recruitment (Ccl5, Ccl2) (Fig. 4A–P). Senolytic drugs did not affect expression of any of the tested genes, suggesting its inability to reduce liver inflammation, fibrosis and senescence in MASLD. Expression of Arg1 (Fig. 4B), a marker of M2 macrophage activation26, was decreased in MASLD, and there was also no effect of senolytic drugs.

Gene expression in the liver of male mice fed with standard diet (SD) or western diet (WD) and treated with placebo (CTL), dasatinib and quercetin (D + Q) and fisetin (FIS). Interleukin 1 alpha (Il1α—A), Arginase-1 (Arg1—B), C–C Motif Chemokine Ligand 5 (Ccl5—C), C–C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (Ccl2—D), Adhesion G Protein-Coupled Receptor E1 (f4/80—E), Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (Tnfα—F), Interleukin 6 (Il6—G), Interleukin 1 Beta (Il1β—H), Lamin B1 (LmnB1—I), Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 1A (Cdkn1a/p21—J), Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A (Cdkn2a/p16—K), High Mobility Group Box 1 (Hmgb1—L), Serpin Family E Member 1 (Serpine1—M), Collagen Type IV Alpha 1 Chain (Col4a1—N), Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain (Col1a1—O), Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 (Fgf21—P). The dotted line represents measures in 3-month-old control male mice. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Different letters indicate statistical difference at P < 0.05 between individual groups when a significant interaction effect was observed.

MASLD-induced increase in serum inflammatory markers was not reverted by senolytics

Serum levels of pro-inflammatory markers TNF-α, KC/GRO and IL-2 increased in mice developing MASLD (Fig. 5A,D,H). However, no effect of senolytic drugs was observed in systemic inflammation. IL-5 (Fig. 5F) increased in MASLD mice that received D + Q treatment only (Fig. 5F).

Serum inflammatory markers in male mice fed with standard diet (SD) or western diet (WD) and treated with placebo (CTL), dasatinib and quercetin (D + Q) and fisetin (FIS). The dotted line represents measures in 3-month-old control male mice. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Different letters indicate statistical difference at P < 0.05 between individual groups when a significant interaction effect was observed.

Testicular gene expression was not affected by MASLD or senolytics

The same genes evaluated in liver were also evaluated in testicles. Although most of the pro-inflammatory/senescence genes were up-regulated by MASLD in liver, the same was not observed in testicles (Fig. 6). We only observed increased testes Tnf expression in MASLD mice receiving D + Q (Fig. 6C).

Testicular gene expression in male mice fed with standard diet (SD) or western diet (WD) and treated with placebo (CTL), dasatinib and quercetin (D + Q) and fisetin (FIS). Interleukin 1 alpha (Il1α—A), Arginase-1 (Arg1—B), C–C Motif Chemokine Ligand 5 (Ccl5—C), C–C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (Ccl2—D), Adhesion G Protein-Coupled Receptor E1 (f4/80—E), Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (Tnf α—F), Interleukin 6 (Il6—G), Interleukin 1 Beta (Il1β—H), Lamin B1 (LmnB1—I), Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 1A (Cdkn1a/p21—J), Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A (Cdkn2a/p16—K), High Mobility Group Box 1 (Hmgb1—L), Serpin Family E Member 1 (Serpine1—M). The dotted line represents measures in 3-month-old control male mice. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Different letters indicate statistical difference at P < 0.05 between individual groups when a significant interaction effect was observed.

Sperm parameters and fertility were not affected by MASLD or senolytics

Sperm concentration and viability were not affected by MASLD nor senolytics (Table 1). Additionally, MASLD did not affect fertility in the mating trial, indicating that MASLD independent of obesity is not harmful to reproductive function in male mice. Senolytics were also not able to affect fertility in healthy nor MASLD mice.

Senescence markers and testicular morphology were not affected by MASLD or senolytics

Testicular senescence as measured by lipofuscin (Fig. 7C) and lamin B1 staining (Fig. 7D) was not affected by MASLD or senolytic treatments. There was also no effect of MASLD and senolytic treatment in seminiferous tubules (Fig. 7A) and lumen diameter (Fig. 7B).

Seminiferous tubule diameter (A), lumen diameter (B), lipofuscin (C) and lamin B1 staining (D) and representative images of sections with lipofuscin (F), lamin B1 (G), and H&E staining (E) of seminiferous tubules with a × 10 magnification in mice fed a standard diet (SD) or western diet (WD) and treated with placebo (CTL), dasatinib and quercetin (D + Q) and fisetin (FIS). The dotted line represents measures in 3-month-old control male mice. Representative images are presented at × 400 magnification. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Different letters indicate statistical difference at P < 0.05 between individual groups when a significant interaction effect was observed.

Discussion

In this study, we provided a choline-deficient WD for a period of 6 months to induce MASLD development, while providing treatment with senolytic drugs during the final 3 months. We observed an increase serum ALT/AST, liver triglyceride accumulation, fibrosis, senescence and inflammatory markers in response to the choline-deficient WD. These are indicators that mice under WD developed MASLD in the absence of obesity, as expected for choline-deficient WD fed mice27,28. However, treatment with senolytics was unable to reduce any measure of liver damage nor liver senescence. Furthermore, we observed that sperm quality, testicular parameters, and fertility were not affected by development of MASLD or senolytic treatment. This suggests that MASLD in the absence of obesity has no clear effect on male fertility.

We observed increased liver damage and senescence markers in mice developing MASLD. Mice induced to MASLD had increased liver size, fibrosis, triglycerides accumulation, serum ALT, and increased expression of extracellular matrix genes (Col1a1, Col4a1) and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the liver (Il1a, Il1b, and Tnfa), similar to observed in previous studies using choline-deficient WD to induce MASLD29. Evaluation of NAS indicate the development of steatohepatitis in choline-deficient WD mice. Cellular senescence is increased in the liver of obese individuals30. Chronic inflammation leads to hepatocyte senescence, contributing to hepatic fibrosis31. Therefore, senescence appears to be involved in the pathogenesis of liver injury and MASLD. However, the role of senescent cells in liver damage and the effect of senolytics is unclear. We observed that senolytics were not able to reduce liver damage or senescence markers in the liver of MASLD mice. Mice with liver DNA repair deficiency have increased accumulation of liver senescent cells, leading to increased fat accumulation7. Treatment of these mice with senolytics (D + Q) reduced senescent cell burden and fat accumulation7, suggesting a central role of senescent cells in the pathogenesis of liver damage. On the other hand, mice exposed to diethylnitrosamine (DEN) and high-fat diet (HFD) to induce MASLD did not have a reduction in senescent cells in the liver with monthly use of D + Q over five months. D + Q increased the progression of liver disease in the DEN/HFD mouse model14, suggesting a negative effect. Treatment of HepG2 and Huh-7 cells in vitro with doxorubicin increased SA-β-galactosidase activity, a marker of senescent cells, which was not reduced by D + Q15. Corroborating with this evidence, we demonstrated that senolytics were not able to reverse any measure of liver damage/senescence in mice developing MASLD. However, future studies should evaluate if incorporating senolytic therapy with the start of choline-deficient WD could prevent liver damage or if higher doses of senolytics are necessary for this condition. Additionally, the age-dependent effect of senolytics in the progression of MASLD should be evaluated.

We observed an increase in liver and serum pro-inflammatory cytokines in mice developing MASLD. However, treatment with senolytics was unable to reverse liver and serum pro-inflammatory state. TNFα is critical in the development of hepatic steatosis associated with metabolic dysfunction32. Clinical studies have shown that as metabolic dysfunction progresses from steatosis to steatohepatitis, TNFα increases in serum, liver, and adipose tissue33. We observed liver and systemic TNFα up-regulation in MASLD mice. Senolytics may reduce systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines, as observed in studies using old12,34 and obese mice35. However, we did not observe a reduction in hepatic and systemic inflammation in mice treated with senolytics. This may indicate that different senescence mechanisms triggered by different stressors, can impair the effectiveness of commonly used senolytics. D + Q treatment was able to reduce systemic and adipose tissue inflammation in mice induced to obesity with a HFD36. However, fisetin and D + Q treatment in young male mice (4–13 months old) receiving chow diet did not affect serum inflammatory markers37. Similarly, in male mice of similar age in our study, no clear beneficial effects of senolytics were observed, regardless of MASLD. This suggests that, in addition to the type of stressors used to induce liver damage, age may play a fundamental role in the accumulation of senescent cells and response to senolytics.

There is evidence indicating strong connections between liver disease and compromised reproductive function. Liver damage can lead to hormonal and metabolic dysfunction, negatively impacting reproductive health. In our study, we observed that MASLD did not affect sperm quality, testicular inflammation/senescence, or fertility. Human studies have demonstrated strong cross-links between male reproduction and liver diseases16. Male rats receiving a HFD developed MASLD and had impaired testicular testosterone synthesis, sperm count and sperm motility18. Treatment of these rats with omega-3 fatty acids reduced liver mass and improved sperm parameters. However, these changes in diet also resulted in reduced adiposity. Others shown that mice receiving a HFD did not develop liver steatosis but also had reduced sperm count19. Despite mice developing MASLD and systemic inflammation in our study, they did not develop obesity. Therefore, most studies showing effects of MASLD in male mice fertility are cofounded with the effects of obesity. Our study indicates that development of MASLD independent of obesity does not affect sperm parameters and fertility of male mice. Both obesity38, and MASLD can increase systemic levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines20,21. Transient inflammation induced by LPS injection is an independent risk for reduced sperm count and decreased testosterone levels in mice22. Despite the increased serum inflammatory markers in mice developing MASLD in our study, no effects on fertility were observed. It is possible that the effects of MASLD on male fertility shown on previous studies are dependent on body mass and adiposity. More studies comparing different dietary patterns directly are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

We did not observe any effect of MASLD on testicular inflammation and senescence. Senolytics were unable to reduce testicular senescence markers. Cellular senescence accumulates differently with age in each tissue, but studies are limited. We observed an increase in the expression of senescence marker genes (Suppl. Fig. 2) and a decrease in lamin B1 (Suppl. Fig. 3) with age in testicles comparing control mice with 3 and 9 months of age. This suggests that there is increased senescence in the testicles that was not affected by MASLD or senolytic treatment. Studies evaluating cellular senescence in the testicles are limited; however, our group previously observed that D + Q treatment in young mice also did not affect fertility rates and testicular senescence23. A study with young (9 to 18 months) and older (7 to 15 years) dogs observed increased number of p21-positive cells with age in the testicles, suggesting increased senescence39. The presence of senescent testicular endothelial cells with aging was demonstrated in vitro. Treatment with senolytics D + Q removed these senescent cells, restoring their supportive capacity compared to endothelial cells from young mice40. Interestingly, the same pro-inflammatory, fibrotic, and senescent cellular markers that we observed increased in the liver with the MASLD were not altered in the testicles. Despite resulting in systemic inflammation, MASLD did not affect testicular inflammation/senescence and therefore did not impact sperm quality and fertility.

In conclusion, senolytic therapy was not able to reduce liver damage and senescence in mice that developed MASLD. Although we showed that MASLD development resulted in systemic inflammation, it did not affect sperm quality and fertility. Overall, our study suggests that the mechanisms of choline-deficient WD-induced MASLD in male mice resulted in increased liver senescence and inflammation that are not reduced by senolytic drugs D + Q and fisetin.

Methods

Animals and treatment

The experiment was approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee from Universidade Federal de Pelotas (028574/2021-33). Three-month-old C57BL/6 male mice (n = 114) were randomly assigned to receive a standard diet (SD, LIP: 12%, CHO: 70%, PTN: 18%, TestDiet®, modified 5TFH) or a choline-deficient WD (LIP: 40%, CHO: 44%, PTN: 16%, TestDiet®, modified 5TFH) ad libitum until 9 months of age (Suppl. Table 1). At 6 months of age, mice were divided into six groups (n = 18/group) to receive senolytics (D + Q or Fisetin) or vehicle control until 9 months of age. Senolytics were administered via oral gavage for three consecutive days once a month (D = 5 mg/kg; Q = 50 mg/kg; fisetin = 100 mg/kg) dissolved in vehicle (60% phosal, 30% PEG400, and 10% ethyl alcohol), according to previously established protocol12,13. Six mice from each group were euthanized at 3 and 9 months of age for liver, testicle and blood collection by cardiac puncture from the left side. Liver samples were collected from the periportal region in all mice. In addition, epididymal sperm was collected from the epididymal tail. At 9 months of age, mice (n = 12/group) were mated with untreated 3-month-old female mice for 8 days to assess pregnancy rates (one male to two female ratio, n = 24 females/group). Body mass and food consumption was measured every 2 weeks.

Semen collection and analysis

For the collection of epididymal sperm, after euthanasia an incision was made in the scrotum, the epididymal tail was pulled out, removed, and placed in a microtube containing 300 µL of culture media (Gibco™ MEM α 1x), preheated to 36.5 °C. The epididymis was then gently fractionated with scissors and incubated for 3 min to release the sperm41. For sperm concentration analysis, 25 µL of the semen solution was diluted in 25 µL of saline-formaldehyde solution. The concentration was assessed by sperm counting using a hemocytometer counting chamber42. Sperm motility analysis was performed using a microscope (Axio Scope A1®, Zeiss, Jena, Germany) coupled with a computer-assisted semen analysis system (CASA, SpermVision®, Minitube, Tiefenbach, Germany). For this, 6 µL of semen sample was placed on a glass slide with a coverslip, and at least six sections were evaluated for each mouse. The variables assessed by the CASA system were average path velocity (VAP), curvilinear velocity (VCL), straight-line velocity (VSL), beat cross frequency (BCF), lateral head displacement amplitude (ALH), total motility (TMO), and progressive motility (PMO).

Testicles and liver histology

One of the testicles and the liver were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in alcohol, cleared in xylene, and then embedded in Paraplast (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Louis, MO, USA). Paraplast blocks were transversely cut into 5 µm sections in the central region of the testicle and liver. The sections were then deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in an alcohol series, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The stained sections were photographed by a camera attached to a microscope (Nikon Eclipse E200, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using TC Capture software (Tucsen Photomics Co.) at a × 10 magnification. For each mouse, 20 round or nearly round seminiferous tubules were randomly chosen. The diameter of the seminiferous tubules and their lumen were measured using Motic 3.0 software (Motic®, Hong Kong, China). For statistical comparison, the average measurements of the 20 seminiferous tubules from a single mouse were used. Liver sections were evaluated for the NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) according to established protocols25.

Lipofuscin staining

Lipofuscin staining was performed using Sudan black dye on a subset of histological slides from each mouse liver and testicles (n = 6/mice). We employed a modified protocol43,44. Image J software (National Institutes of Health—USA) was used to quantify the lipofuscin staining area.

Picrosirius red staining

Staining of collagen fibers was performed with Picrosirius red dye on histological slides of liver tissue (n = 3/mice), according to a previous protocol45. The slides were then stained with 0.1% Picrosirius solution (Direct red 80, Sigma-Aldrich/365548 and picric acid) and washed with acidified water (glacial acetic acid). For image analysis, section (3 sections/mouse) were observed at × 100 magnification using a 552 nm laser to acquire fluorescence on a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP8). Image J software (National Institutes of Health—USA) was used to quantify the collagen staining area.

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence analysis, testicular samples were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated with an alcohol chain gradient as previously described46. Anti-Lamin B1 (ab133741, Abcam) was diluted in 1.5% BSA solution and used at a dilution of 1:100047. Antigen retrieval was performed in moist heat for 3 min at boiling point in citrate solution (pH 6.0). Nonspecific background staining was reduced by covering tissue sections with 10% BSA and 7% goat serum. The slides were incubated overnight with the primary antibody in a humid chamber at 4 °C, for 1 h with secondary antibody Alexa Fluor® 488 (ab150077, Abcam) and for 3 min with DAPI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). Slides were mounted with a drop of mounting medium (Fluoroshield, Sigma-Aldrich, St Lois, USA). For analysis, one area of each section (3 sections/mouse) from three mice per group was acquired at × 100 magnification using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP8). Sequential scanning was employed using the 488 nm laser to visualize Alexa 488 and the 405 nm UV lasers to visualize DAPI staining. Fluorescence intensity was calculated using Image J® software to calculate the proportion of positive cells in each testis image.

Serum cytokines and biochemistry

Blood samples were collected at the time of euthanasia and centrifuged at 1500×g to separate serum. Serum samples were evaluated for concentrations of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) using commercial kits (Bioclin, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil and Labtest Virtue Diagnostic, Lagoa Santa, MG, Brazil), using an automated equipment (Cobas Mira S from Roche®, Basel, Switzerland). Additionally, a panel of pro-inflammatory markers was evaluated by chemiluminescence-based assay (V-PLEX Proinflammatory Panel 1 Mouse Kit, K15048D-1, MSD, Gaithersburg, MD, EUA).

Gene expression

The liver and testicle RNA was extracted and processed as described before48. Beta-2 microglobulin (B2m) and peptidylprolyl isomerase A (Ppia) were evaluated as candidates housekeeping gene using the geNorm software42. Ppia was considered the most stable and used as internal control. Relative gene expression was calculated using the comparative delta CT method49. The primer sequences used in these analyses are shown in Suppl. Table 2.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 6.0. Repeated measures ANOVA was used for evaluating body mass followed by a Tukey post-hoc test. Two-way ANOVA was used for analysis of other parameter considering the effects of the diet, senolytics and its interaction followed by a Tukey post-hoc test. Chi-square was used to evaluate pregnancy rate. P values lower than 0.05 were considered significant. Data is presented as mean ± SEM.

Data availability

Data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Pouwels, S. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A review of pathophysiology, clinical management and effects of weight loss. BMC Endocr. Disord. 22, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-00980-1 (2022).

Schierwagen, R. et al. Seven weeks of Western diet in apolipoprotein-E-deficient mice induce metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis with liver fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 5, 12931. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12931 (2015).

Castellanos-Tapia, L. et al. Mediterranean-like mix of fatty acids induces cellular protection on lipid-overloaded hepatocytes from western diet fed mice. Ann. Hepatol. 19, 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2020.06.005 (2020).

Dave, A. et al. Consumption of grapes modulates gene expression, reduces non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and extends longevity in female C57BL/6J mice provided with a high-fat western-pattern diet. Foods 11, 984. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11131984 (2022).

Lian, C. Y., Zhai, Z. Z., Li, Z. F. & Wang, L. High fat diet-triggered non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A review of proposed mechanisms. Chem. Biol. Interact. 330, 109199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109199 (2020).

Raubenheimer, P. J., Nyirenda, M. J. & Walker, B. R. A choline-deficient diet exacerbates fatty liver but attenuates insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in mice fed a high-fat diet. Diabetes 55, 2015–2020. https://doi.org/10.2337/db06-0097 (2006).

Ogrodnik, M. et al. Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis. Nat. Commun. 8, 15691. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15691 (2017).

Hu, L. et al. Why senescent cells are resistant to apoptosis: An insight for senolytic development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 822816. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.822816 (2022).

Secomandi, L., Borghesan, M., Velarde, M. & Demaria, M. The role of cellular senescence in female reproductive aging and the potential for senotherapeutic interventions. Hum. Reprod. Update 28, 172–189. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmab038 (2022).

Huang, W., Hickson, L. J., Eirin, A., Kirkland, J. L. & Lerman, L. O. Cellular senescence: The good, the bad and the unknown. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-022-00601-z (2022).

Kirkland, J. L. & Tchkonia, T. Senolytic drugs: From discovery to translation. J. Intern. Med. 288, 518–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13141 (2020).

Xu, M. et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med. 24, 1246–1256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0092-9 (2018).

Yousefzadeh, M. J. et al. Fisetin is a senotherapeutic that extends health and lifespan. EBioMedicine 36, 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.09.015 (2018).

Raffaele, M. et al. Mild exacerbation of obesity- and age-dependent liver disease progression by senolytic cocktail dasatinib + quercetin. Cell Commun. Signal. 19, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-021-00731-0 (2021).

Kovacovicova, K. et al. Senolytic cocktail dasatinib+quercetin (D+Q) does not enhance the efficacy of senescence-inducing chemotherapy in liver cancer. Front. Oncol. 8, 459. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2018.00459 (2018).

Li, Y., Liu, L., Wang, B., Chen, D. & Wang, J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and alteration in semen quality and reproductive hormones. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 27, 1069–1073. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000000408 (2015).

Kim, S. et al. A low level of serum total testosterone is independently associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 12, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-12-69 (2012).

Li, Y. et al. Impairment of reproductive function in a male rat model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and beneficial effect of N-3 fatty acid supplementation. Toxicol. Lett. 222, 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.05.644 (2013).

Gomez-Elias, M. D. et al. Association between high-fat diet feeding and male fertility in high reproductive performance mice. Sci. Rep. 9, 18546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54799-3 (2019).

Targher, G. et al. NASH predicts plasma inflammatory biomarkers independently of visceral fat in men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16, 1394–1399. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.64 (2008).

Haukeland, J. W. et al. Systemic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is characterized by elevated levels of CCL2. J. Hepatol. 44, 1167–1174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.011 (2006).

Rokade, S. et al. Transient systemic inflammation in adult male mice results in underweight progeny. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 86, e13401. https://doi.org/10.1111/aji.13401 (2021).

Garcia, D. N. et al. Dasatinib and quercetin increase testosterone and sperm concentration in mice. Physiol. Int. 110, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1556/2060.2023.00192 (2023).

Matsumoto, M. et al. An improved mouse model that rapidly develops fibrosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 94, 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/iep.12008 (2013).

Kleiner, D. E. et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 41, 1313–1321. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.20701 (2005).

Alisi, A. & Vajro, P. Pre-natal and post-natal environment monitoring to prevent non-alcoholic fatty liver disease development. J. Hepatol. 67, 451–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.04.016 (2017).

Nakae, D. et al. High incidence of hepatocellular carcinomas induced by a choline deficient L-amino acid defined diet in rats. Cancer Res. 52, 5042–5045 (1992).

Denda, A. et al. Expression of inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase but not prevention by its gene ablation of hepatocarcinogenesis with fibrosis caused by a choline-deficient, L-amino acid-defined diet in rats and mice. Nitric Oxide 16, 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.niox.2006.07.002 (2007).

Yang, M. et al. Western diet contributes to the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in male mice via remodeling gut microbiota and increasing production of 2-oleoylglycerol. Nat. Commun. 14, 228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-35861-1 (2023).

Papatheodoridi, A. M., Chrysavgis, L., Koutsilieris, M. & Chatzigeorgiou, A. The role of senescence in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and progression to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 71, 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30834 (2020).

Jurk, D. et al. Chronic inflammation induces telomere dysfunction and accelerates ageing in mice. Nat. Commun. 2, 4172. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5172 (2014).

Burger, K. et al. TNFalpha is a key trigger of inflammation in diet-induced non-obese MASLD in mice. Redox Biol. 66, 102870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2023.102870 (2023).

Jorge, A. S. B. et al. Body mass index and the visceral adipose tissue expression of IL-6 and TNF-alpha are associated with the morphological severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in individuals with class III obesity. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 12, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2016.03.009 (2018).

Iske, J. et al. Senolytics prevent mt-DNA-induced inflammation and promote the survival of aged organs following transplantation. Nat. Commun. 11, 4289. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18039-x (2020).

Palmer, A. K., Gustafson, B., Kirkland, J. L. & Smith, U. Cellular senescence: At the nexus between ageing and diabetes. Diabetologia 62, 1835–1841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4934-x (2019).

Palmer, A. K. et al. Targeting senescent cells alleviates obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction. Aging Cell 18, e12950 (2019).

Fang, Y. et al. Sexual dimorphic metabolic and cognitive responses of C57BL/6 mice to Fisetin or Dasatinib and quercetin cocktail oral treatment. Geroscience 45, 2835–2850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00843-0 (2023).

Avtanski, D., Pavlov, V. A., Tracey, K. J. & Poretsky, L. Characterization of inflammation and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-induced male C57BL/6J mouse model of obesity. Anim. Model Exp. Med. 2, 252–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/ame2.12084 (2019).

Merz, S. E., Klopfleisch, R., Breithaupt, A. & Gruber, A. D. Aging and senescence in canine testes. Vet. Pathol. 56, 715–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985819843683 (2019).

Ozawa, M. et al. Age-related decline in spermatogenic activity accompanied with endothelial cell senescence in male mice. iScience 26, 108456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108456 (2023).

Oliveira, J. B. A. et al. The effects of age on sperm quality: An evaluation of 1,500 semen samples. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 18, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.5935/1518-0557.20140002 (2014).

Khaki, A. et al. Beneficial effects of quercetin on sperm parameters in streptozotocin-induced diabetic male rats. Phytother. Res. 24, 1285–1291. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.3100 (2010).

Evangelou, K. & Gorgoulis, V. G. Sudan Black B, the specific histochemical stain for lipofuscin: A novel method to detect senescent cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 1534, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6670-7_10 (2017).

Ansere, V. A. et al. Cellular hallmarks of aging emerge in the ovary prior to primordial follicle depletion. Mech. Ageing Dev. 194, 111425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2020.111425 (2021).

Briley, S. M. et al. Reproductive age-associated fibrosis in the stroma of the mammalian ovary. Reproduction 152, 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-16-0129 (2016).

Schneider, A. et al. Primordial follicle activation in the ovary of Ames dwarf mice. J. Ovarian Res. 7, 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-014-0120-4 (2014).

Freund, A., Laberge, R. M., Demaria, M. & Campisi, J. Lamin B1 loss is a senescence-associated biomarker. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 2066–2075. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E11-10-0884 (2012).

Stout, M. B., Liu, L. F. & Belury, M. A. Hepatic steatosis by dietary-conjugated linoleic acid is accompanied by accumulation of diacylglycerol and increased membrane-associated protein kinase C epsilon in mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 55, 1010–1017. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201000413 (2011).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by CAPES, CNPq and FAPERGS. This project has been made possible in part by Grant Number 1023 from the Global Consortium for Reproductive Longevity & Equality (GCRLE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JDH performed experiments, data interpretation, analysis, and wrote the manuscript. DNG, BMZ, MMB, GCP, JVVI, CB, MF, SAM, BMA, TCO, HCR, CIL, RAV assisted in experiments, data analysis, and manuscript revision. JBM, MMM and MBS assisted in experimental design, data interpretation, and manuscript revision. AS performed data analysis, interpretation, and assisted in manuscript preparation and revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hense, J.D., Garcia, D.N., Zanini, B.M. et al. MASLD does not affect fertility and senolytics fail to prevent MASLD progression in male mice. Sci Rep 14, 17332 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67697-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67697-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Translating cellular senescence research into clinical practice for metabolic disease

Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2026)

-

Targeting senescent hepatocytes for treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and multi-organ dysfunction

Nature Communications (2025)