Abstract

Solar eclipse has remarkable effect on behavior of animals. South India experienced a 97% magnitude annular eclipse on December 26, 2019 during 08:04–11:04 h with the totality phase appeared during 09:25–09:30 h. We investigated whether the foraging activity of the bees was limited by the eclipse, what bees are affected most, and which part of the eclipse was critical for bee activities to understand how a group of insects that rely the Sun, the sunlight, and the sun rays for their navigation and vision behaves to the eclipse. We opted to watch the bees in their foraging ground, and selected the natural flower populations of Cleome rutidosperma, Hygrophila schulli, Mimosa pudica, and Urena sinuata—some of the bee-friendly plants—to record the visitor richness and visitation rate on the flowers on eclipse and non-eclipse days and during the hour of totality phase and partial phase of the eclipse. Fewer flower-visiting species were recorded on the eclipse day than on the non-eclipse days, but in the period of totality, very few bee species were active, and limited their activity to only one population of C. rutidosperma. Visits of honey bees and stingless bees were affected most, but not that badly of solitary bees and carpenter bees. Bees, particularly the social bees use Sun for navigation and deciphering information on forage sources to fellow workers. The eclipse, like for many other animals, might hamper bees’ orientation, vision, and flight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plants and animals use a wide variety of environmental cues for their biological activities, such as flowering, migration, navigation, foraging, hibernation, aestivation among others1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Daylight and ambient heat and radiation from the Sun are critical for almost all major biological activities of organisms including behavior4,6,7,9. Daylight is a major abiotic predictor of blooming in plants10. Some animals use the Sun’s magnetic field for migration, foraging and navigation. For instance, bees use the Sun’s position for their diurnal movement and navigation between nests and foraging grounds11. The nocturnal bees use the dim light of the Moon and the Stars for their daily navigation12,13,14,15. Large-scale spatial or astronomical factors, such as solar and lunar eclipse, despite are rare, can affect the environment and biological activities of animals5,16. Because these events are rare, their effects on bioactivities of animals and plants have been investigated less.

The solar eclipse occurs when the Moon gets between the Earth and the Sun, and the Moon casts a shadow over the Earth17. Its magnitude can be varied considerably based on the angular diameter of the moon and the Sun that are coinciding at their centers18. It lasts for a few minutes to many hours, but the duration of annular event can be lasted only for a few minutes. During the solar eclipse, the air temperature and light intensity drop suddenly7,9,19,20.

Because organisms’ response to weather conditions (especially temperature and light) is different among species, their response to solar eclipse can be different7,9. Behavioral responses to total solar eclipse have been observed in fishes21, copepods22, seabirds23, antelope16, and cattle24. Animals responded differently during the annular and total solar eclipses. For instance, the ground squirrels’ locomotor activities increased during partial solar eclipse25; Hamadryas baboons, on the other hand, became less active during solar eclipse26; the captive chimpanzees took a gesture towards the Sun during the annular solar eclipse27; European ground squirrel was non-responsive during partial eclipse28; hippopotamus and many birds in Mana Pools National Park behaved as though it was dusk, and baboons stopped feeding5. Wild chimpanzees, however, showed no change in their foraging behavior during an annular solar eclipse in Mahale Mountains National Park in Tanzania29. In the Phylum Arthropoda, the effect of solar eclipse has been studied in desert cicadas30, orb-weaving spiders4 and crickets, katydids, butterflies, moths, and honey bees31. The latter study found that the activity of crickets, katydids, butterflies, moths and honeybees went abnormal during the 1932 total solar eclipse.

Bees generally are active during sunshine period and use the Sun as a compass for navigation32. While most bees opt to fly during bright sunny warm days, some manage to fly in very dim light conditions—including moonlight and even starlight12,13,33,34,35. Even though some standard and informal studies on the flight activities of Apis spp. have been carried out during the period of solar eclipse9,36,37,38,39, limited information is available on the effect of solar eclipse on pollinators in foraging ground (but see, Galen et al.9). Galen et al.9 found that the flight activity of honey bees, bumblebees, and some solitary bees dropped suddenly during the totality phase of the 2017 annular solar eclipse in the U.S. Divan37 found that the stingless bees reduced their foraging activity and disoriented during the totality phase of solar eclipse in Karnataka. In Dehradun, the activity of Apis dorsata was not affected during a low magnitude partial solar eclipse occurred during 07:37–09:20 h36. Apis mellifera stopped visiting foraging ground during the annular phase of solar eclipse38.

On December 26, 2019, parts of south India experienced an annular solar eclipse (Fig. 1). It had a magnitude of about 97%18. The annular event of the eclipse was visible from parts of Saudi Arabia to parts of Indonesia (Fig. 1). In Kerala in south India, the annular event was total and visible in and around Cheruvathur (12.18 N; 75.14E) in Kasaragod district with its highest magnitude. The annularity in the west coast of India, where the study took place, was during 09:25–09:30 h. However, the region had experienced partial eclipse during 08:05 h through 11:30 h Indian Standard Time (Fig. 2). Our observations were made from Kannapuram and south Kanhangad, which located about 10 km south and north of Cheruvathur as a crow flies, respectively. The study sites were non-cloudy and non-windy on the day of eclipse and during our observation. The darkness experienced by the sites was only during the eclipse period.

In this study, we report the effect of solar eclipse on the visitation characterisitcs of bees to four bee-friendly plant species—Cleome rutidosperma DC. (Cleomaceae), Hygrophila schulli M.R. Almeida and S.M. Almeida (Acanthaceae), Mimosa pudica L. (Fabaceae), and Urena sinuata L. (Malvaceae). By analyzing the visitation characteristics of bees during peak and partial period of the eclipse on the day of eclipse and several non-eclipse days, we studied whether the eclipse limited the foraging activities of the bees and which part of the eclipse was critical for the bee activities.

Material and methods

Study species

The four plant species we selected for the present study are good bee-friendly plants and grow abundantly as a community in lowland agro-landscapes of the study locality. They have visitors throughout their anthesis period, and their anthesis period coincides with the annular period of the solar eclipse. They also vary on their morphological traits. Mimosa pudica has deep purplish head inflorescences; U. sinuata has purplish pink solitary shallow flowers; H. schulli has violet deep zygomorphic flowers; and C. rutidosperma has violet shallow flowers (Table 1; Fig. 2). All of them are visited by the bees both for pollen and nectar.

Sampling

Three plant species—H. schulli, M. pudica, and U. sinuata—were studied in Kannapuram (11° 96″ 85.97′ N, 75° 32″ 10.12′ E) and C. rutidosperma was studied in south Kanhangad (12° 25.11′ N, 75° 13.15′ E). Both the sites have experienced ring of fire in the same Indian Standard Time. In each location, four to five populations that stood in a kilometer radius were selected for each plant species to record the flower visitors on non-eclipse days (NED). They were watched for 3–5 days before or after the eclipse day to find out the visitation rate of the bees on normal days (control). On the day of eclipse (ED), due to logistic difficulties and manpower shortage, we watched flowers of H. schullii, M. pudica, and U. sinuata in two populations and C. rutidosperma in four populations. For the former three species, we could divide the observation period of eclipse day into partial-eclipse hour (PEH; 08:45–09:15 h) and peak eclipse hour (EH; 09:20–09:50 h). Therefore, we could compare the visitation rate to flowers on peak eclipse and partial eclipse hours of eclipse day. On non-eclipse days, we did not divide the observation period into two due to operational difficulties and watched the flowers continuously during 09:00–10:00 h, which covered the time of annual eclipse. Therefore, in order to study the effect of day type on pollinator frequency, we pooled the visits of peak eclipse hour and partial eclipse hour of eclipse day and compared it with the visitation rate of non-eclipse days. For, C. rutidosperma, we watched the flowers on eclipse day and non-eclipse days during 09:00–10:00 h continuously. However, for all the four plant species, we recorded the visitation rate during the few minutes of the ring of fire on eclipse day. Since that period had lasted only for a few minutes, we used the hour-long observation data to study the effect of solar eclipse on pollinator activity.

We recorded the visits of only bee species in the present study. Wherever we could not attend the populations in person, we deputed one of our family members or friends to videograph the visits with the help of a mobile camera. The video tracks and photographs were analyzed later to identify the visitor species/ morphospecies. Whenever more than one visitor species visited the focal flowers at a time, we videographed the visits.

All the observations were made on natural populations. Therefore, the number of flowers available in the observed populations varied among days. On eclipse day, an average of 50 ± 11 (N = 4) C. rutidosperma, 74 ± 18 (N = 2) U. sinuata, 101 ± 16 (N = 2) H. schullii, and 116 ± 11 (N = 2) M. pudica flowers were watched to record flower visitors. On non-eclipse days, we watched an average of 35 ± 8 (N = 12) C. rutidosperma, 41 ± 16 (N = 13) U. sinuata, 67 ± 14 (N = 14) H. schullii, and 103 ± 27 M. pudica flowers (N = 12). To account for this difference in the number of flowers, we used visitation rate (visits/flower−h) as a response variable in the statistical analyses. We also identified the visitor species to family and genus and to species or morphospecies. Three species of solitary bees were unidentified.

Statistical analysis

The observed number of species (species richness) and visitation rate (visits/flower−h) were considered as the response variables in the present study. First, we calculated the sum visits of all bee species to the flowers of each species for each of its population. We divided the sum visits of all bees by the number of flowers watched in that population to find the visitation rate for that population. The visitor richness was also recorded for each plant population. We did this for all the plant populations that we sampled during eclipse and non-eclipse days. We used Kruskal–Wallis rank ANOVA test to compare the visitation rate of bees to the flowers of each plant species on peak and partial eclipse hours of eclipse day and the peak eclipse hour of non-eclipse days. For C. rutidosperma, we had only two levels—peak eclipse hour of eclipse day and peak eclipse hour of non-eclipse day—for the visitation rate, which we compared using Wilcoxon rank test.

We fitted the visitation rate and visitor richness of plant populations of the day types (eclipse day and non-eclipse day) and the plant species in Linear Mixed Effect Model (LMM) and Generalized Linear Mixed Effect Model (GLMM), respectively to study the effect of day type, plant species, and the interaction between the day type and plant species on the visitation characteristics of the bees. We fitted site as a random factor in these models. The significance of LMM was tested using two-way ANOVA and the significance of GLMM was tested using Wald’s χ2 test using the R-package, car.

We used analysis of covariance to discern the crucial drivers of visitation rate of bees. In this model, day type (eclipse day/non-eclipse day), plant species, number of focal flowers in plants, and hour of observation from the commencement of anthesis were used as the potential predictors of the visitation characteristics. We used these factors in interaction terms and non-interaction terms and checked whether the interaction model was robust than the other model using a goodness-of-fit test using ANOVA. This resulted that the interaction model was not different from the non-interaction model either for the visitation rate (p = 0.52) or species richness (p = 0.07). Therefore, we used the results of non-interaction models in the results. All the analyses were performed in R 3.2.3.

Results

Flower visitors

The flowers of four plant species together received the visits of a total of 19 species of bees on non-eclipse days. It includes three species each of carpenter bees (Xylocopa bryorum, X. latipes, and X. acutipennis) and honey bees (Apis cerana, A. dorsata, and A. florea), one species of stingless bee (Tetragonula iridipennis), and 12 species of solitary bees. On the eclipse day, eleven species of bees (one species of honey bee, one species of stingless bee, three species of carpenter bees, and six species of solitary bees) visited the flowers of four plant species. However, during the peak half an hour of the eclipse, only the flowers of C. rutidosperma received some visits of T. iridipennis, Braunsapis sp., and Amegilla zonata (Table 2). However, all these recorded visits come from one out of the four populations monitored during this period. The other three plant populations of C. rutidosperma, and populations of other three plant species received no visits.

Effect of eclipse on visitation rate and species richness

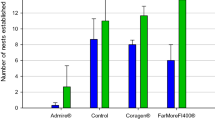

The overall visitation rate to the flowers of C. rutidosperma was different between the eclipse hour of eclipse and non-eclipse days (W = 0, DF = 1, p < 0.01). The overall visitation rate to the flowers of H. schullii (χ2 = 7.45, DF = 2, p = 0.024), M. pudica (χ2 = 7.4, DF = 2, p = 0.024), and U. sinuata (χ2 = 7.81, DF = 2, p = 0.02) was different among the peak hour of eclipse day, partial hour of eclipse day, and the eclipse hour of non-eclipse day (Fig. 3). Although some bees visited the flowers during the partial eclipse period, the visitation rate was lower than that of the corresponding period of non-eclipse days (Fig. 3).

The visitation rate of overall bees to the flowers of four plant species in the peak eclipse hour (EH) and partial eclipse hour (PEH) of eclipse day (ED) and non-eclipse days (NED). CR Cleome rutidosperma, HS Hygrophila schulli, MP Mimosa pudica, US Urena sinuata, ED Eclipse day, NED Non-eclipse day.

The interaction between day type (eclipse day vs. non-eclipse day) and plant species predicted the variability in visitation rate of bees (F3,63 = 5.58, p < 0.01), but not the observed richness of bees (Wald χ2 = 5.8, DF = 3, p = 0.12). The visitation rate reduced significantly during the hour of eclipse for all plant species.The richness was also decreased significantly for all plant species but M. pudica on the hour of eclipse (Table 3, Fig. 3). Honey bees (F1,18 = 19.5, p < 0.01) and stingless bees (F1,24 = 4.4, p = 0.04) made significantly lower number of visits during solar eclipse. The visitation rate of carpenter bees (F1,12 = 0.48, p = 0.5) and solitary bees (F1,24 = 2.04, p = 0.16), however, was not affected by the eclipse (Table 4). The visitation rate of honey bees (F2,18 = 32.3, p < 0. 01) and stingless bees (F3,24 = 10.7, p < 0.01) was predicted by the interaction term of day type and plant species. Apart from the day type, number of focal flowers was a crucial driver of richness (F1,20 = 7.23, p = 0.01), but not for the visitation rate (F1,20 = 2.55, p = 0.13). The hours since anthesis was also a predictor of visitation rate of the bees (F1,20 = 4.43, p = 0.04).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the effect of an annular solar eclipse—a rare celestial event—on the visitation characteristics of bees to the flowers of four shrubby bee-friendly plants in their natural populations. Overall, the annular eclipse reduced the visitation rate of bees to the flowers. Our results agree to the findings of Divan37, Briceno and Ramirez38, Woyke et al.39, and Galen et al.9, which suggest that bees’ flight activity can be reduced during annular eclipse. However, partial eclipse has no major effect on the foraging activity of bees9,36.

The annular eclipse during the study was total in the sampled sites and had lasted for a considerable period of time. The eclipse also had coincided with some of the peak flight activity and foraging activity period of the bees. December is a winter month for the present tropical warm study area, so, the activity of bees peaks after 08:00 h (personal observation), the period when the solar eclipse had occurred. Though should have been quantified, it appeared that the eclipse made no visible changes on the morphology of the flowers. Although the visitation pattern of the bees during partial eclipse period was monitored, the scope of the present study was not extended to explore how the bees responded after the eclipse period. However, as part of another research, we had collected data for M. pudica during post-eclipse hour on both the eclipse and non-eclipse days in one of the sampled populations. During the eclipse hour, this population had 0.11 visits/flower−h from one species of bee, which improved to 1.03 visits/flower−1 in the post-eclipse period on the day of eclipse. On normal days, an average of 1.48 visits/ flower−h was made by 4 species of bees. It suggests that the bees can resume their visits immediately after the darkest phase of the eclipse ceases. Galen et al.9 found an overall cessation in buzzing activity of bumblebees, honey bees, and some solitary bees during the totality period of an annular eclipse in the U.S. As they have noted, the 3 min-long total annular eclipse period of our study also had witnessed no visits of any bee species in any of our plant species. However, we used the sample of whole hour of solar eclipse, including the partial phase of eclipse for analysis, because, we were unsure whether the no visits in the 3 min was ‘normal’ as part of bees’ visitation bouts or because of eclipse. Therefore, all the four plant species had a non-zero mean visitation rate and visitor richness on the day of eclipse, unlike Galen et al.9.

Total annular eclipse leads to very poor light and quick reduction in ambient temperature9. Both the environmental variables though are critical for bee activities, light is very crucial for bee navigation particularly for avoiding obstacles in flight. The drastic reduction in the overall bee activity, may therefore, due to their poor visibility. Among the four functional groups of bees examined in the present study, stingless bees and honey bees reduced their flight activity drastically during the solar eclipse. The commonality between the bees of these two guilds is that they are social bees. These bees are known to reduce their flight activity in response to light condition. The 97% magnitude eclipse considerably slashed the natural sunlight from 09:15 h through 10:15 h. This can affect vision of bees, except for the bees that can see things in dim light. For instance, the visits of carpenter bees and solitary bees are not affected by the eclipse. This is likely, because carpenter bees are known for their flight activity in the dim lights and nocturnal hours12,40. Although three species of carpenter bees were active on non-eclipse days, only X. bryorum was active during the period of eclipse. Among honey bees, A. dorsata was the only one found active during the eclipse hour. The study by Roonwal36 found that the foraging activity of A. dorsata was not affected by partial solar eclipse. It may be, however noted that both X. bryorum and A. dorsata visited the flowers of only M. pudica during the hour of eclipse. While X. bryorum was an exclusive visitor of M. pudica flowers, A. dorsata was a visitor to both M. pudica and U. sinuata in the whole data. Among four species of plants, only in M. pudica, the visitor richness was unaffected by the solar eclipse (Table 3). Similarly, we also found that the timing of eclipse with reference to the anthesis time affect the visitation rate of the bees. Therefore, the effect of eclipse on visitation rate to the flowers is likely to be affected by the bee species or the day type interacting with the plant species and the timing of observation with reference to the commencement of anthesis.

Among the four plant species monitored in the present investigation, C. rutidosperma was the most important bee plant (Table 3). Except for the carpenter bees, bees of all other functional groups made a strong association with this plant. Therefore, the visitation pattern of the bees alone was sufficient to understand how important the eclipse is for the bees. Stingless bees’ visits reduced several folds in C. rutidosperma and in other three species of plants. Divan37 while watching a colony of T. iridipennis found that the returning workers located nest holes with a greater difficulty during a partial eclipse. We grouped several species of solitary bees into one functional group. This perhaps explains why the visits of solitary bees were not affected by eclipse. Species-centric large study may be required to understand the effect of solar eclipse on buzzing activity of individual solitary bee species.

The present study considered visitation rate and observed richness of bees on the flowers – the two common traits that the pollinator activity studies measure frequently and use in the statistical models used to test various hypotheses – to measure the effect of solar eclipse on bee activities. Bee visitation rate is a proxy of abundance of the bees. Though only a subset of the solitary bees is attracted to pan traps, we recommend them as the additional method to sample bees and to estimate the abundance. Because we selected bee-friendly plants and not plant communitites, topology of plant-pollinator networks, such as diversity, nestedness, and connectance , was not assessed, and could be part of future studies. Because the study didn’t investigate the response of the focal flowers to the eclipse, we don’t know whether the decreasing number of visits during eclipse period was also due to any flower-specific factors such as nectar availability.

Conclusion

Our study that watched the bee foraging activity on four bee-friendly plants shows that the solar eclipse reduced the flight activity of the bees. Solar eclipse is a rare yet a major natural phenomenon that can affect the normal behavior of animals. While a few species including the domestic animals do not respond to the abnormal dimming of light on normal days, many captive and wild animals do behave abnormally during the period of eclipse. The most noticed abnormal behavior is the preparedness for roosting or homing. In bees, the solar eclipse, in particular the annular and total eclipse, can affect the flight activity due to poor vision and poor navigation rather than the dropping ambient temperature. The present study and the previous reports suggest that bees by large are affected by solar eclipse and demonstrate that how important the Sun, the sunlight, and abnormal darkness on sunny days for the bees’ navigation. It is suggested that bee and pollinator sampling may be done during clear days and avoid cloudy days. Though cloudiness reduce light on ground, the eclipse not only reduce the light, but also reduce radiation and heat on the ground and happen all of a sudden and unseasonal unlike monsoon or rainy season. Therefore, the response of the bees to cloudy days may still be better than the eclipse days, though that needs more studies. It is very unlikely that the rare celestial events like solar eclipse shape the evolution of insect flight, particularly those that use the Sun as a compass, because such events were rare in the past. However, observational studies of bees on eclipse days might render clues for how insects that use and do not use the Sun for flight, foraging, and navigation behave to solar eclipse.

Data availability

All the data are visible in the descriptive plots. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kalmus, H. Comparative physiology: Navigation by animals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 26, 109–130 (1964).

Rusak, B. & Zucker, I. Biological rhythms and animal behavior. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 26, 137–171 (1975).

Périlleux, C., Bernier, G. & Kinet, J. Darkness promotes flowering in the absolute long-day requiring plant, Lolium temulentum L. Ceres. J. Exp. Bot. 48, 349–351 (1991).

Uetz, G. et al. Behavior of colonial orb-weaving spiders during a solar eclipse. Ethology. 96, 24–32 (1994).

Murdin, P. Effects of the 2001 total solar eclipse on African wildlife. Astron. Geophys. 42, 40–42 (2001).

Puskadija, Z. et al. Influence of weather conditions on honey bee visits (Apis mellifera carnica) during sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) blooming period. Poljoprivreda 13, 230–233 (2007).

Lee, H. & Kang, H. Temperature-driven changes of pollinator assemblage and activity of Megaleranthis saniculifolia (Ranunculaceae) at high altitudes on Mt. Sobaeksan, South Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 42, 31 (2018).

Afsharyan, N. P., Sannemann, W., Léon, J. & Ballvora, A. Effect of epistasis and environment on flowering time in barley reveals a novel flowering-delaying QTL allele. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 893–906 (2020).

Galen, C. et al. Pollination on the dark side: Acoustic monitoring reveals impacts of a total solar eclipse on flight behavior and activity schedule of foraging bees. Ann. Entomol. 112, 20–26 (2018).

Van Doorn, W. G. & Kamdee, C. Flower opening and closure: An update. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 5749–5757 (2014).

Von Frisch, K. The Dance Language and Orientation of Bees (Harvard University Press, 1967).

Somanathan, H., Borges, R. M., Warrant, E. J. & Kelber, A. Nocturnal bees learn landmark colours in starlight. Curr. Biol. 18, 996–997 (2008).

Somanathan, H., Borges, R. M., Warrant, E. J. & Kelber, A. Visual ecology of Indian carpenter bees I: Light intensities and flight activity. J. Comp. Physiol A. 194, 97–107 (2008).

Wcislo, W. T. & Tierney, S. M. Behavioral environments and niche construction: The evolution of dim-light foraging in bees. Biol. Rev. 84, 19–37 (2009).

Borges, R. M. Dark matters: Challenges of nocturnal communication between plants and animals in delivery of pollination services. Yale J. Biol. Med. 91, 33–42 (2018).

Mahato, A. K. R., Majumder, S. S., De, J. K. & Ramakrishna, A. Activities of Blue bull, Boselaphus tragocamelus during partial solar eclipse: A case study in captivity. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 25, 269–274 (2013).

Nymphas, E. F., Adeniyi, M. O., Ayoola, M. A. & Oladiran, E. O. Micrometeorological measurements in Nigeria during the total solar eclipse of 29 March, 2006. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 71, 1245–1253 (2009).

Kurien, A. M., Mani, H. S. & Virmani, A. The annular eclipse of 26th December 2019 as to be seen in Coimbatore. Resonance. 24, 1273–1286 (2019).

Reber, T. et al. Effect of light intensity on flight control and temporal properties of photoreceptors in bumblebees. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 1339–1346 (2015).

Wiantoro, S., Narakusumo, R. P., Sulistyadi, E., Hamidy, A. & Fahri, F. Effects of the total solar eclipse of March 9, 2016 on the animal behavior. J. Trop. Biol. Conserv. 16, 137–149 (2019).

Jennings, S., Bustamante, R. H., Collins, K. & Mallinson, J. Reef fish behavior during a total solar eclipse at Pinta Island, Galapagos. J. Fish Biol. 53, 683–686 (2005).

Sherman, K. & Honey, K. A. Vertical movements of zooplankton during a solar eclipse. Nature. 227, 1156–1158 (1970).

Tramer, E. J. Bird behavior during a total solar eclipse. Wilson Bull. 112, 431–432 (2000).

Rutter, S. M., Tainton, V., Champion, R. A. & Le Grice, P. The effect of a total solar eclipse on the grazing behavior of dairy cattle. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 79, 273–283 (2002).

Kavanau, J. L. & Rischer, C. E. Ground squirrel behavior during a partial solar eclipse. Ital. J. Zool. 40, 217–221 (1973).

Gil-Burmann, C. & Beltrami, M. Effect of solar eclipse on the behavior of a captive group of hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas). Zoo Biol. 22, 299–303 (2003).

Branch, J. E. & Gust, D. A. Effect of solar eclipse on the behavior of a captive group of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Am. J. Primatol. 11, 367–373 (2005).

Spoelstra, K., Strijkstra, A. M. & Daan, S. Ground squirrel activity during the solar eclipse of August 11, 1999. Z Saugetierkunde. 65, 307–308 (2000).

Nakamura, M. & Nishie, H. < NOTE> An annular solar eclipse at Mahale: Did Chimpanzees exhibit any response?. Pan Africa News. 23, 9–13 (2016).

Sanborn, A. F. & Phillips, P. K. Observations on the effect of a partial solar eclipse on calling in some desert cicadas (Homoptera: Cicadidae). Fla. Entomol. 75, 285–287 (1992).

Wheeler, W. M., MacCoy, C. V., Griscom, L., Allen, G. M. & Coolidge, H. J. Observations on the behavior of animals during the total solar eclipse of August 31, 1932. Am. Acad. Arts Sci. 70, 33–70 (1935).

Michener, C. D. The Bees of the World (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

Lythgoe, J. N. The Ecology of Vision (Oxford University Press, 1979).

Somanathan, H. & Borges, R. Nocturnal pollination by the carpenter bee Xylocopa tenuiscapa (Apidae) and the effect of floral display on fruit set of Heterophragma quadriloculare (Bignoniaceae) in India. Biotropica. 33, 78–89 (2001).

Warrant, E. Vision in the dimmest habitat on earth. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural. Behav. Physiol. 190, 765–778 (2004).

Roonwal, M. Behavior of the rock bees, Apis dorsata Fabr. during a partial solar eclipse in India. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B 22, 281–286 (1957).

Divan, V. V. Honey bee behavior during total solar eclipse. Indian Bee J. 42, 97–99 (1980).

Briceno, R. & Ramirez, W. Activity of Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and some spiders (Araneidae) during the 1991 total solar eclipse in Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 41, 291–293 (1993).

Woyke, J., Jasinski, Z., Cezary, F. & Woyke, H. Flight activity of Apis mellifera foragers at the hive entrance during 86% eclipse of sun. Pszczel Ćesz Nauk. 44, 239–249 (2000).

Sinu, N. & Sinu, P. A. Temporal consistency in foraging time and bouts of a carpenter bee in a specialized pollination system. Curr. Sci. 122, 213 (2022).

Acknowledgements

PAS thanks Science Engineering Research Board (Grant No. 7170) for the Core Research Grant, which funded this research. We thank Athira Lakshmanan, Neethu Sinu, and Oneema Sinu for field assistance. Necessary permissions were obtained from the owners of the premises to watch the flowers. We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and inputs into the original version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.A.S. conceived the idea and planned the study. P.A.S., A.J. and S.V. collected and curated data. P.A.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sinu, P.A., Jose, A. & Varma, S. Impact of the annular solar eclipse on December 26, 2019 on the foraging visits of bees. Sci Rep 14, 17458 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67708-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67708-0