Abstract

In therapies, curcumin is now commonly formulated in liposomal form, administered through injections or creams. This enhances its concentration at the cellular level compared to its natural form ingestion. Due to its hydrophobic nature, curcumin is situated in the lipid part of the membrane, thereby modifying its properties and influencing processes The aim of the research was to investigate whether the toxicity of specific concentrations of curcumin, assessed through biochemical tests for the SK-N-SH and H-60 cell lines, is related to structural changes in the membranes of these cells, caused by the localization of curcumin in their hydrophobic regions. Biochemical tests were performed using spectrophotometric methods. Langmuir technique were used to evaluate the interaction of the curcumin with the studied lipids. Direct introduction of curcumin into the membranes alters their physicochemical parameters. The extent of these changes depends on the initial properties of the membrane. In the conducted research, it has been demonstrated that curcumin may exhibit toxicity to human cells. The mechanism of this toxicity is related to its localization in cell membranes, leading to their dysfunction. The sensitivity of cells to curcumin presence depends on the saturation level of their membranes; the more rigid the membrane, the lower the concentration of curcumin causes its disruption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

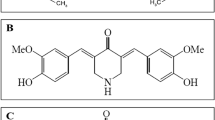

Curcumin (1,7-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione) is the active compound of a polyphenolic nature obtained from Curcuma longa (turmeric) rhizomes1,2.

The diketo group exhibits keto-enol tautomerism, which can exist in different types of conformers depending on the environment3. In solvents, it exists as cis–trans isomers. It is a hydrophobic molecule. It is almost insoluble in water and easily soluble in polar solvents. Curcumin absorbs light in the UV–VIS range. The spectrum of curcumin has two strong absorption bands, one in the visible range with a maximum range from 410 to 430 nm and another band in the UV range with a maximum at 265 nm4. In the literature, the spectral and photochemical properties of curcumin in various solvents have been well described, which helps understand its biological photo-reactivity in different cellular microenvironments5,6,7. This knowledge has allowed the use of curcumin as a photosensitizer in photodynamic therapy6. Understanding the chemical properties of curcumin is crucial for effectively introducing it into cells and utilizing its therapeutic properties.

Several studies have confirmed that curcumin possesses various pharmacological and biological properties, including antioxidant8,9, antibacterial10,11, immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory2,12 antidiabetic13, anticancer14,15, hepatoprotective16, anti-Alzheimer's17,18, anti-rheumatic19.

Due to the fact that the use of curcumin in liposomal form is becoming more and more common, the concentration of this compound, in cells can reach much higher level, definitely exceeding the amounts that can enter the body when applied in natural form. Too high concentrations of this compound may cause toxic effects. This is of particular importance in the case of curcumin, because its hydrophobic chemical nature causes its molecules to localize within cell membranes20. Such localization may have positive effects, because curcumin can protect fatty acids residues from oxidation, but at the same time, its location between hydrocarbon chains may disturb their mobility within lipid bilayer. As a consequence, the mechanical properties of membranes (such as fluidity, stiffness, permeability) can be significantly changed, which in turn can disrupt the proper functioning of membrane proteins21. In this way, curcumin indirectly, by changing the mechanical properties of the lipid part of the membranes, can affect processes such as transport across membranes, reception of signals from the environment, nerve conduction, i.e. processes on which most metabolic pathways in cells depend.

There are many studies in the literature indicating that curcumin affects membranes by changing their properties22,23,24,25. These studies refer to significantly simplified single-component systems25,26 and are often limited to theoretical considerations27,28.

However, there are no reports in which model studies have been compared with native systems, where reactions resulting from the amount of membrane components and the number of biochemical processes occurring simultaneously in cells can influence the effects of curcumin observed in an isolated model system.

Therefore, the aim of the study was to examine the effect of various concentrations of curcumin on the lipid parts of cell membranes in a strictly defined model system and to relate this effect to that observed in cells. Thus, an attempt was made to correlate changes in the structural and mechanical properties of the membranes with the potential toxicity of curcumin to cells. Two types of cells were selected, whose membranes significantly differ in properties: that is the human promyelocyte line HL-60, characterized by a relatively high level of membrane unsaturation29,30,31 and neuroblastoma cells SK-N-SH, having a much higher degree of saturation of fatty acids residues in membranes32,33,34. For such systems, changes in the physicochemical parameters of model membranes were analyzed using the Langmuir technique. Langmuir monolayers serve as good models for membranes, providing the ability to control membrane composition and molecular packing. They offer a good means of investigating how substances present in the membrane environment can alter their mechanical properties. In the next step, both cytotoxicity and the degree of damage to native membranes were assessed (MTT, LDH, MDA tests).

Materials and methods

Materials

To investigate the influence of curcumin on model membrane systems, the following lipids were employed: phospholipids: 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), 1-oleoyl-2-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC); 1-hexacosanoyl-d4-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (Lyso PC); 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC); l-α-phosphatidylethanolamine (PE, Brain); 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), sphingomyelin (SM, Brain), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (DPPS), cholesterol (Chol). All lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (USA/Canada) instead of cholesterol (from Merck). Lipids’ shares in the multicomponent systems that mimick membranes of investigated cells were based on data of Charalampous32, Yip et al.33, Jabkubec et al.34—for SK-N-SH cell line (64% PC mix (96% POPC, Lyso PC 2%, 18:1 PC 2%), PE Brain 19%, SM Brain 18%), and of Ip and Cooper29, Chabot et al.30, Berkowic et al.31—for HL-60 cell line (15.96%mol DPPS, 18.64%mol DPPC; 32.42%mol DOPC and 32.98%mol DOPE). The cholesterol and phospholipid ratio for the model systems were 0.35 for HL-60 and 0.21 for SK-N-SH.

Chloroform were used as a high purity solvent to obtain lipids’ solutions, but only for DPPS dissolution; 9:1 v/v chloroform:methanol (POCH (Avantor Poland) were used.

Curcumin (Sigma—Aldrich, Poland, CAS no 458-37-7) was dissolved in ethanol to obtain final concentration.

Curcumin was blended with lipid solutions, including DOPC, DPPC, and phospholipid mixtures representing SK-N-SK and HL-60 membrane models. The molar ratio of lipid to curcumin (M:M) varied at 1:4, 1:8, 1:64, 1:128, and 1:256, respectively. These solutions were employed to generate Langmuir's isotherms.

Langmuir technique

A Langmuir trough (KSV, Finland) was employed to generate surface pressure isotherms. Lipid monolayers were formed by spreading lipid solutions, with or without curcumin, on a phosphate buffer subphase (0.01 M aqueous, pH 7.4). A Wilhelmy platinum plate was utilized to measure surface tension at the air–liquid interface. Uniform conditions were maintained across all measurements: a compression rate of 5 mm/min and a temperature of 25 °C ± 1 °C.

Each isotherm was conducted 4–5 times, initiating measurements with a fresh application of the lipid solution. From the obtained data, the static modulus of compression (Cs−1) was derived using the equation35,36:

where Am is the mean area per molecule, and π-represents the surface pressure.

Presenting the results in the form of the static compression modulus dependence on surface pressure facilitates the determination of the monolayer's condition and any phase changes it undergoes37. These results were recalculated and expressed as percentage changes.

Cell cultures

The HL-60 cell line, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, was cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 0.01% penicillin–streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The human neuroblastoma cell line SK-N-SH, sourced from The European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures, was cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.01% penicillin–streptomycin. Both cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

The culture medium, serum, and antibiotics were provided by CytoGen GmbH. In all instances, curcumin at the appropriate concentration (0–50 μM) was added to the cultures, and they were incubated at 37 °C. After 24 h, the cells were ready for the subsequent experiments.

Measurement of cell viability (MTT assay)

The cell viability was assessed using the tetrazolium salt colorimetric assay (MTT). Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/cm3 in a 0.2 cm3 volume. Following treatment with the respective curcumin solution, 0.05 cm3 of MTT solution (5 mg/cm3) was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, 0.4 cm3 of DMSO was introduced to each well and allowed to stand for 5 min. The supernatant absorbance was then measured at 570 nm using a BioTek Epoch microplate reader. Cell viability, expressed as the percentage of cell survival (% SDH), was determined by the formula:

here, A1 represents the absorbance of cells exposed to different curcumin concentrations, and A0 is the absorbance of the control.

Calculation of the Median Lethal Dose (LD50)

The MTT method was employed to assess viability, and its outcomes directly align with the number of surviving cells. The results obtained for the maximum curcumin concentration tested (50 μM) facilitate the evaluation of curcumin toxicity in biological systems. Utilizing the Behrens method38, the median lethal dose (LD50) was determined from the data presented.

Membrane damage assay (LDH assay)

Cells at a density of 1 × 106/cm3 were treated with varying concentrations of curcumin for 24 h. In the initial step, eppendorf tubes received 0.5 cm3 of sodium pyruvate and 0.01 cm3 of NADH, were vortexed, and then placed in a 37 °C heating block. Following a 10-min incubation, 0.15 cm3 of cell supernatant was transferred to eppendorf tubes and returned to the thermoblock (37 °C) for 30 min. Subsequently, 0.5 cm3 of dye (diphenylhydrazine) was added to the samples and thoroughly mixed. The samples were once again stored at 37 °C for 1 h. After this incubation period, 0.2 cm3 of the sample was applied to the plate, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Determination of lipid peroxidation (MDA concentration)

Membrane lipid peroxidation was gauged photometrically by measuring the absorbance of the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and malondialdehyde (MDA) complex at 532 nm.

Cells were plated in 46-well plates with curcumin (as per the specified concentrations and durations) at 1 × 104 cells per well in a 0.25 cm3 volume. Following the treatment, samples were collected and centrifuged (1000×g, 5 min). To the resulting supernatants, 0.5 cm3 of trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (0.5%) was added. The mixtures were vortexed for 1 min and lysed by sonication for 5 min. After centrifugation (10 min, 10,000×g), 0.4 cm3 of the supernatant was combined with 1.25 cm3 of TCA (20%) and TBA (0.5%), and the mixture was heated for 30 min in a dry thermoblock (100 °C). Following cooling, the absorbance at 532 nm was measured using an MDA molar extinction coefficient of 155/mM−1/cm−1.

Statistical analysis

We conducted three to six independent analyses for each tested variant and calculated the average (± standard deviation). To identify significant differences compared to the controls, we utilized the SAS ANOVA procedure. The statistical analysis involved Duncan's multiple range test with a significance level set at p < 0.05. All statistical tests were executed using STATISTICA 13.3.

Results

Membrane models

In order to determine changes in the mechanical properties of the lipid membranes of HL-60 and SK-N-SH cells, lipid mixtures were made that reflected the composition of the lipid parts of the membranes of these cells. These models have been composed in such a way as to contain both the appropriate amounts of individual polar lipids as well as to have the appropriate degree of fatty acids` residues saturation.

The ratios of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids in solutions S to US were: 48–52% for SK-N-SH and for HL-60: 34.6% S to 65.4% US. The cholesterol and phospholipids (PL) were mixed at the proportions—for SK-N-SH: 79% PL, 21% Chol, and for HL—60: 65% PL, 35% Chol. For SK-N-SH the membrane solutions were prepared as follow32,33,34: 64% PC (mixed POPC, lyso PC and 18:1 PC Brain), 19% PE brain, 18% SM brain. Based on the literature data29,30,31, for HL-60 model membrane system was composed of: 15.96 mol% DPPS, 18.64 mol% DPPC, 32.42 mol% DOPC and 32.98 mol% DOPE.

Due to the fact that both cell models used in the studies significantly differ in the saturation of fatty acids` residues, the effect of curcumin on simplified, one-component membrane models, i.e. monolayers of DPPC (extremely saturated) and DOPC (unsaturated), was checked (Fig. 1a,b).

The course of surface pressure isotherms of monolayers of DPPC and DOPC containing curcumin clearly indicates that this compound is incorporated into monolayers, locating between lipid molecules. However, the influence of curcumin is significantly more pronounced in the saturated system. The differences in the effects of curcumin on these systems show the lowest levels (concentrations) of curcumin that cause a change in the isotherm course. These extreme lipid:curcumin ratios are 256:1 for saturated lipid DPPC and 64:1 for DOPC.

Due to the fact that animal cell membranes contain noticeable amounts of cholesterol—a lipid with a completely different molecular structure (characteristic sterane system), the effect of curcumin on pure cholesterol monolayers was also checked (Fig. 1c). In this case as well, the effect of curcumin was noticeable with the extreme lipid:curcumin ratio at which changes in monolayer properties were recorded was 64:1.

Monolayers made of lipid mixtures mimicking the membranes of the examined cells were also modified by the presence of curcumin. The lipid:curcumin ratios causing changes in the isotherms were significantly different for studied model mixtures being 8:1 for HL-60 cells and 64:1 for neuroblastoma cells (Fig. 1d,e).

For the monolayers of all the tested systems, the compression modulus Cs−1 was calculated. An exemplary course of the compression modulus as a function of the surface pressure is shown in Fig. 2.

The dependence of the compression modulus on the surface pressure shows significant changes with changes of curcumin level. For the DOPC:curcumin system with increasing curcumin level the compression modulus decreased, while for the SK-N-SH:curcumin model this effect was opposite.

To better illustrate the changes resulting from the presence of curcumin, the Cs−1 values at 30 mN/m (pressure corresponding to native membranes)39 were determined for each tested system and its percentage changes relative to the control were calculated (Fig. 3).

Percentage change in the compression modulus at π = 30 nNm obtained on the basis of surface pressure isotherms of lipid:curcumin mixtures at different molar ratios. The changes were related to the Cs−1 value for the control system (pure lipid monolayer) assumed as 100% and marked on the graphs with a straight line.

In Fig. 3, the control (100%) is marked with a straight line. For each of the tested systems, the presence of curcumin causes a change in the Cs−1 value. With the increase in curcumin concentration in one-component systems, i.e. DPPC, DOPC, cholesterol the Cs−1 values decrease. The largest changes (about 40%) were observed for DPPC and cholesterol at curcumin levels of 8:1 and 4:1 respectively. Lower concentrations of curcumin caused smaller changes, with that still observed for DPPC at a lipid:curcumin ratio of 128:1, and for cholesterol at 64:1. For the unsaturated lipid (DOPC) the effect of curcumin was significantly smaller, the largest decrease reached of about 20% at the ratio of DOPC to curcumin equal to 4:1. The influence of curcumin was noticeable at a curcumin level of 64:1.

In the case of the membrane models for the examined cells, the direction of Cs−1 changes in the was opposite. With the increase in the concentration of curcumin, an increase in the value of this parameter was observed. For the HL-60 model this effect was smaller being of about 10% and observed only at the lipid:curcumin ratio of 8:1. For the SK-N-SH cell model Cs−1 value increased by about 25% at the 8:1 and 4:1 levels and this change, although smaller (10%) was observed at the 64:1 ratio.

Native cell membranes

First, the effect of curcumin on human cells of the SK-N-SH and HL-60 lines was evaluated using the MTT test, which determines the mitochondrial activity of the cells.

To assess the biological action of curcumin, cells were exposed to different concentrations of curcumin (5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 μM) for 24 h (as seen in Fig. 4).

The cell viability determined by MTT assay. SK-N-SH and HL-60 cells were exposed for 24 h to various concentrations of curcumin (5–50 µM). Cell viability was expressed as percentage fraction (referred to the untreated control cells) of living cells. Values represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Significant differences were marked with different letters: for the SK-N-SH cell line—uppercase letters; for the HL-60 cells—lowercase letters. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between the tested cell lines (p ≤ 0.05).

Changes in cell viability of both tested lines depended on the concentration used. With increasing curcumin concentration a decrease in the number of viable cells was observed. Differences between the two tested cell lines in reaction to curcumin were visible when using 30, 40 and 50 μM solutions of this polyphenol. In human neuroblastoma cells, treatment with the highest curcumin concentration (50 μM) resulted in an approximately 50% decrease in cell viability. HL-60 cells responded less to this concentration, with only about a 25% decrease in cell viability.

The results of cell viability allowed determination of the median lethal dose (LD50 median lethal dose) values based on the Behrens' method38 with the following assumptions: the number of cells per measurement point is constant, the absorbance determined in the MTT method is correlated with the number of live cells (if the cell is experiencing a higher dose, it has survived all lower doses; if the cell dies at the lower dose, it would die at all higher doses). Then, the percentage mortality was calculated for each dose of curcumin and LD50 values were obtained from appropriate graphs.

For SK-N-SH cells, LD50 (mg L−1/1 × 106cells) was 65.46, and for HL-60 LD50 (mg L−1/1 × 106cells) was 98.33. Data show that LD50 values for the HL-60 cells were much higher than for SK-N-SH.

The next stage of the work was to check to what extent curcumin affects the membranes of the tested cells. For this purpose, the LDH test was used to assess the degree of cell membrane damage and the MDA level to assess the degree of lipid peroxidation.

The integrity of the HL-60 and SK-N-SH membranes after exposure to different concentrations of curcumin was determined by measuring the amount of released lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). This enzyme is secreted into the environment due to mechanical damage to the cell membrane and cell death. Thus, the level of extracellular LDH was measured as an indicator of cytotoxicity. (The LDH assay gives information about the stability of the cell membrane).

Figure 5 shows that the integrity of the cell membrane after treatment with curcumin depends on the type of the cell line. With increasing concentration of curcumin, a progressive increase in LDH activity in the culture medium was observed. Treatment of SK-N-SH cells with higher concentrations of curcumin (30, 40, 50 μM) resulted in a greater efflux of this enzyme (by about 8, 10, 12% over controls, respectively). The membranes of promyelocytic cells disintegrated to a lesser extent (at the curcumin level of 30 and 40 μM, just 3 and 5% increase in LDH concentration was observed). Only exposure to the highest, 50 μM, concentration of curcumin caused an 11% increase in LDH concentration in the culture medium, comparable to SK-N-SH (compared to the cells of the control group).

Membrane damage of SK-N-SH and HL-60 cells determined by LDH assays after contact with curcumin (5–50 µM). The percentage of LDH leakage was referred to untreated control cells. Values represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences: for the SK-N-SH cell line, capital letters; for the lowercase HL-60 cell line. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between the tested cell lines (p ≤ 0.05).

The level of membrane lipid peroxidation in the examined cells after treatment with curcumin was determined by measuring the MDA (Fig. 6). Specific, only higher concentrations of curcumin (20–50 µM) were selected for this experiment. The comparison of the results shows that in SK-N-SH and HL-60 cells, the level of membrane lipid peroxidation increases with increasing curcumin concentration. The results obtained for the two cell lines are statistically similar. The highest concentration of curcumin used (50 μM), in the case of SK-N-SH cells, resulted in an approximately 48% increase (relative to the control) in malondialdehyde concentration. For HL-60 cells, an approximately 41% increase of MDA concentration was noted.

The effect of curcumin on SK-N-SH and HL-60 cells measured by degree of lipid peroxidation (concentration of MDA). The cells were treated for 24 h with selected curcumin concentrations (20; 30; 40; 50 µM).Values represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences: for the SK-N-SH cell line uppercase; for the HL-60 cell line lowercase letters.

Discussion

The bioavailability of curcumin due to its poor solubility in water (≤ 0.125 mg/L), rapid metabolism, degradation and elimination is low40,41, hence in clinical trials even high doses curcumins (administered orally) do not show toxicity42,43,44. However, curcumin is also often used in liposomal form (administered in the form of injections or creams), and then its doses can be multiplied at the cellular level. In a situation where the effect on cancer cells is targeted, the initiation of apoptosis of these cells by liposomal curcumin is a desirable effect45,46,47,48.

Unfortunately, curcumin in this form is also often administered for other purposes, e.g. cosmetic49,50,51,52. Then, determining safe concentrations of curcumin at the cellular level is extremely important.

Due to the hydrophobic character of curcumin, it has an affinity for the interior of membranes. Experimental studies have confirmed that this compound is localized in membranes20,53 increasing their permeability and reducing their thickness21,26. However, the effect of curcumin on membranes depends on many factors. Molecular dynamics simulations (MD) have shown that action of curcumin depends on the proximity of lipids, as well as their type27,28. MD simulations provide information on individual impacts from different complex regions of membranes containing a variety of proteins and lipids54,55. They can mimic realistic systems56,57, however, MD simulations of curcumin action in lipid bilayers are rather limited25. Therefore, there is still a need to answer the questions in what concentration range curcumin can have a beneficial effect on the cell and whether the concentration level from which the effect of curcumin can be considered toxic and to what extent it depends on the type of membrane or depends on the type of cell.

For this reason, in the work the effects of the presence of curcumin on the membranes were studied for three systems, i.e.: (1) single-component models—monolayers of single lipids differing in the saturation of fatty acids` residues: DOPC, DPPC (the main class of animal cell lipids) and cholesterol (a lipid of a different chemical nature—steroid, abundantly found in animal cells); (2) multi-component monolayers with the lipid composition of HL-60 and SK-N-SH cell membranes and (3) native membranes—in vitro cells of the HL-60 and SK-N-SH lines.

The obtained results showed that exposition of each of the tested systems to contact with curcumin modifies the physicochemical properties of the membrane, but the extent of changes depends on the lipid packing in the membrane. For the tested one-component systems, the presence of curcumin increases the limiting surface area per single molecule at maximal lipid packing in the monolayer (Alim) and the pressure at which it collapses (πcoll). The change of these parameters indicates that curcumin locates between lipid molecules, modifying their mutual interactions. However, the most sensitive parameter turned out to be the compression modulus (Cs−1), the value of which gives information about the elasticity of the monolayer (the higher the Cs−1 value, the greater the stiffness of the layer). In the case of both the studied phosphatidylcholines and cholesterol, the presence of curcumin resulted in a decrease in the Cs−1 value, i.e. their stiffness decreased, and the percentage change of Cs−1 value was significantly higher for those systems (cholesterol and DPPC) that are initially characterized by its high value indicating greater stiffness of monolayer.

Comparison of the results for DPPC and DOPC monolayers, i.e. for lipids with the same polar parts, but a different saturation of fatty acids’ residues, indicates that it is the nature of the hydrophobic part of the molecules that has a decisive impact on how much the presence of curcumin disturbs the initial mechanical properties of the membrane. Comparison of curcumin limiting concentrations giving noticeable changes in the properties of the monolayer showed that in the case of saturated lipids, the disturbance of the monolayer was already visible at the lipid:curcumin ratio of 256:1, while for the monolayer of unsaturated lipids it appeared at the ratio of 64:1. For cholesterol, this disorder-producing ratio was also 64:1.

Such large differences in the effect of curcumin for saturated and unsaturated systems were verified for multicomponent systems that are equivalent to the lipid part of the membrane, but for cells whose membranes significantly differ in the saturation of fatty acids. The results obtained for these models confirmed that curcumin had a significantly greater effect on the membrane parameters of neuroblastoma cells (SK-N-SH) with these effects observed even at the lipid:curcumin ratio of 64:1, while for promyelocytic cells (HL-60) only at the ratio 8:1.

We know from current literature research that curcumin affects lipid order at different depths within the membrane. It slightly increases the mobility of phospholipid polar headgroups. Along the acyl chain, it enhances ordering effects. In frozen liposome suspensions, curcumin enhances water penetration. Specifically, it affects the membrane center and polar headgroup region. Intermediate positions along the acyl chain are less affected. Curcumin likely adopts a transbilayer orientation within the membrane. It may form oligomers spanning opposite bilayer leaflets. These effects are compared to other protective natural dyes like lutein and zeaxanthin58. These experiments prove that curcumin localizes between lipid molecules in the membrane. However, the extent of modifications it will cause by penetrating their interior will depend on the initial ordering of the lipids. In membranes containing saturated lipids, molecules are tightly packed due to the possibility of easier geometric fitting and therefore the formation of stronger interactions. Introducing curcumin molecules between such ordered lipids more disrupts their arrangement than introducing curcumin into membranes containing unsaturated lipids. When fatty acid chains contain unsaturated bonds, this causes a curvature in the chain resulting in their separation, decreasing interactions and forming microspaces between them. Such a membrane is more fluid and loosely packed, so the introduction of curcumin molecules there will disrupt this system to a lesser extent. In summary, when the membrane is initially more ordered and rigid, the introduction of curcumin will disrupt it to a greater extent, leading to more serious disruptions in the functioning of the proteins in these membranes and causing greater physiological disturbances.

Due to the fact that many metabolic processes are closely related to the operation of membranes, even a slight modification of their properties can disrupt the functioning of cells. Therefore, comparative tests indicating the level of curcumin toxicity were performed, for both tested cell lines. For this purpose, the MTT test was used to detect metabolically active cells. It is widely used for in vitro drug toxicity testing59.

Changes in cell viability of both studied lines were observed depending on the curcumin concentration. The toxic curcumin concentration for SK-N-SH cells turned out to be already at the level of 20 μM, while the greatest effects were observed at its highest concentration used, i.e. 50 μM. This concentration also clearly shows differences in the sensitivity to the curcumin presence of SK-N-SH and HL-60 cells being most visible in the MTT test. About 75% of HL-60 cells survived, while SK-N-SH only 48% at the highest dose of curcumin used (50 μM). On the different sensitivity of the tested cells indicate also the values of the average lethal dose (LD50), which for SK-N-SH cells was 65.46 μM, and for HL-60 as much as 98.33 μM. Tests of cell membrane damage in the process of peroxidation—MDA and membrane continuity failure test—LDH membranes were also performed for the studied cell lines. The results of these tests correlate with the obtained data for cell viability and LD50 values. Greater membrane damage is observed for SK-N-SH cells. Several reports suggest that curcumin may induce ROS60,61,62. Other reports suggest that curcumin suppresses ROS production at low concentrations, and induces ROS production at high concentrations63. The mechanism of ROS increase induced by curcumin is largely discussed in relation to its structure and interaction with transition metals62. Another possible mechanism of the pro-oxidative action of curcumin is its interaction with enzymes, which could lead to ROS production64,65. Furthermore, curcumin present in membranes, may by increasing their polarity, allow for the penetration of a greater amount of water-soluble free radicals or transition metal ions, which may initiate or re-initiate lipid peroxidation.

Comparison of all obtained results, both physicochemical analyses of membrane models and biochemical results performed for cells in vitro, clearly indicates that the mechanism of curcumin toxicity is related to the localization of its molecules within lipid membranes, which, by changing their properties leads to disturbances in metabolic processes within cells, and consequently, their death. The obtained results also prove that the toxicity of curcumin depends on the level of lipid membrane saturation. The higher the level of fatty acid saturation, the greater the disturbance caused by the presence of curcumin.

Due to the fact that in the human body, the membranes of different cells differ in their lipid composition, the effect of curcumin on each type of cell may be different. Particularly important are the nerve cells (studied in this work), because they are characterized by an exceptionally high content of lipids in their membranes, as well as a high degree of fatty acid saturation. Therefore, when liposomal curcumin therapy is considered, it is very important to check the effects of its action, especially on the nervous system, which from a biological point of view plays a superior role in the body, and any damage of nervous cells may have serious consequences for health.

Conclusions

The conducted experiments clearly showed that curcumin, when directly applied to cells, is toxic to them. The mechanism of toxicity of this compound is related to the disruption of the mechanical properties of membranes by locating it between lipid molecules. The extent of membrane modification caused by the presence of curcumin depends on the saturation of fatty acids. The higher the degree of fatty acid saturation, meaning the stiffer the membrane initially, the lower doses of curcumin lead to significant disturbances. Comparison of the toxicity of curcumin for HL-60 cells and nerve cells confirmed (as shown in model studies) that the disruption of membrane structure due to the presence of curcumin correlates with damage to native membranes, ultimately leading to cell death.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Alim :

-

The limiting area per molecule representing the maximal density of a layer

- Chol:

-

Cholesterol

- Cs −1 :

-

Static compression modulus

- CU:

-

Curcumin

- DMEM:

-

Dullbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- DOPC:

-

1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (18:1)

- DOPE:

-

1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (18:1)

- DPPC:

-

1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (16:0)

- DPPS:

-

1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (16:0)

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- LD50 :

-

Median lethal dose

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- Lyso PC:

-

1-Hexacosanoyl-d4-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- MD:

-

Molecular dynamics simulations

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- PE:

-

l-α-Phosphatidylethanolamine

- POPC:

-

1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- SM:

-

Sphingomyelin

- TBA:

-

Thiobarbituric acid

- TCA:

-

Trichloroacetic acid

References

Mirzaei, H. et al. Curcumin: A new candidate for melanoma therapy?. Int. J. Cancer. 139(8), 1683–1695. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30224 (2016).

Boroumand, N., Samarghandian, S., Hashemy, S.I. (2018) Immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects of curcumin. J. Herbmed. Pharmacol. 7, 211−219. https://doi.org/10.15171/jhp.2018.33

Priyadarsini, K. I. Photophysics, photochemistry and photobiology of curcumin: Studies from organic solutions, bio-mimetics and living cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 10, 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2009.05.001 (2009).

Priyadarsini, K. I. The chemistry of curcumin: From extraction to therapeutic agent. Molecules 19, 20091–20112. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules191220091 (2014).

Chignell, C. F. et al. Spectral and photochemical properties of curcumin. Photochem. Photobiol. 59, 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05037.x (1994).

Dahll, T. A., Bilski, P., Reszka, K. J. & Chignell, C. F. Photocytotoxicity of curcumin. Photochem. Photobiol. 59, 290–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05036.x (1994).

Khopde, S. M., Indira Priyadarsini, K., Palit, D. K. & Mukherjee, T. Effect of solvent on the excited-state photophysical properties of curcumin. Photochem. Photobiol. 72, 625–631. https://doi.org/10.1562/0031-8655(2000)0720625EOSOTE2.0.CO2 (2000).

Ak, T. & Gülçin, I. Antioxidant and radical scavenging properties of curcumin. Chem. Biol. Interact. 174(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2008.05.003 (2008).

Chang, C. et al. Encapsulation in egg white protein nanoparticles protects anti-oxidant activity of curcumin. Food Chem. 280, 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.124 (2019).

Negi, P. S., Jayaprakasha, G. K., JaganMohanRao, L. & Sakariah, K. K. Antibacterial activity of turmeric oil: A byproduct from curcumin manufacture. J. Agric. Food Chem. 47(10), 4297–4300. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf990308d (1999).

Bomdyal, R.S., Shah, M.U., Doshi, Y.S., Shah, V.A., Khirade, S.P. (2017) Antibacterial activity of curcumin (turmeric) against periopathogens-An in vitro evaluation. J. Adv. Clin. Res. Insights. 4(6), 175–180. https://doi.org/10.15713/ins.jcri.188

Saw, C. L. L., Huang, Y. & Kong, A. N. Synergistic anti-inflammatory effects of low doses of curcumin in combination with polyunsaturated fatty acids: Docosahexaenoic acid or eicosapentaenoic acid. Biochem. Pharmacol. 79(3), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.030 (2010).

Wójcik, M., Krawczyk, M., Woźniak L.A. Antidiabetic activity of curcumin: Insight into its mechanisms of action. in Nutritional and Therapeutic Interventions for Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome. Academic Press. 385–401 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812019-4.00031-3.

Panda, A. K., Chakraborty, D., Sarkar, I., Khan, T. & Sa, G. New insights into therapeutic activity and anticancer properties of curcumin. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 9, 31. https://doi.org/10.2147/JEP.S70568 (2017).

Bhardwaj, S., Tomar, M. S., Rathi, N. & Upadhyay, S. An overview on anti-carcinogenic properties of curcumin. J. Pharm. Innov. 8(5), 770–772 (2019).

Xie, Y. L. et al. Curcumin attenuates lipopolysaccharide/d-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury by activating Nrf2 nuclear translocation and inhibiting NF-kB activation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 91, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2017.04.070 (2017).

Ono, K., Hasegawa, K., Naiki, H. & Yamada, M. Curcumin has potent anti-amyloidogenic effects for Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils in vitro. J. Neurosci. Res. 75, 742–750. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.20025 (2004).

Hamaguchi, T., Ono, K. & Yamada, M. Curcumin and Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci. Therap. 16(5), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00147.x (2010).

Panaro, M. A. et al. The emerging role of curcumin in the modulation of TLR-4 signaling pathway: Focus on neuroprotective and anti-rheumatic properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(7), 2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072299 (2020).

Kunwar, A. et al. Quantitative cellular uptake, localization and cytotoxicity of curcumin in normal and tumor cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1780, 673–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.11.016 (2008).

Jaruga, E., Sokal, A., Chrul, S. & Bartosz, G. Apoptosis-independent alterations in membrane dynamics induced by curcumin. Exp. Cell. Res. 245, 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1006/excr.1998.4225 (1998).

Jaruga, E. et al. Apoptosis-like, reversible changes in plasma membrane asymmetry and permeability, and transient modifications in mitochondrial membrane potential induced by curcumin in rat thymocytes. FEBS Lett. 433, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00919-3 (1998).

Ingolfsson, H. I., Koeppe, R. E. & Andersen, O. S. Curcumin is a modulator of bilayer material properties. Biochemistry. 46, 10384–10391. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi701013n (2007).

Khajavi, M. et al. Oral curcumin mitigates the clinical and neuropathologic phenotype of the Trembler-J mouse: A potential therapy for inherited neuropathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 438–453. https://doi.org/10.1086/519926 (2007).

Ileri Ercan, N. Understanding interactions of curcumin with lipid bilayers: A coarse-grained molecular dynamics study. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59(10), 4413–4426. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00650 (2009).

Hung, W. C. et al. Membrane-thinning effect of curcumin. Biophys. J. 94, 4331–4338. https://doi.org/10.1529/biophysj.107.126888 (2008).

Jalili, S. & Saeedi, M. Study of curcumin behavior in two different lipid bilayer models of liposomal curcumin using molecular dynamics simulation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 34, 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2015.1030692 (2016).

Lyu, Y., Xiang, N., Mondal, J., Zhu, X. & Narsimhan, G. Characterization of interactions between curcumin and different types of lipid bilayers by molecular dynamics simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 122, 2341–2354. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b10566 (2018).

Ip, S. H. & Cooper, R. A. Decreased membrane fluidity during differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemia cells in culture. Blood. 56(2), 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V56.2.227.227 (1980).

Chabot, M. C., Wykle, R. L., Modest, E. J. & Daniel, L. W. Correlation of ether lipid content of human leukemia cell lines and their susceptibility to 1-O-octadecyl-2-O-methyl-rac-glycero-3-phosphocholine. Cancer Res. 49(16), 4441–4445 (1989).

Berkovic, D. et al. The influence of 1-β-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine on the metabolism of phosphatidylcholine in human leukemic HL 60 and Raji cells. Leukemia. 11(12), 2079–2086. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2400860 (1997).

Charalampous, C. Levels and distributions of phospholipids and cholesterol in the plasma membrane of neuroblastoma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. BBA-Biomembranes 556, 38–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-2736(79)90417-6 (1979).

Yip, C. M., Elton, E. A., Darabie, A. A., Morrison, M. R. & McLaurin, J. Cholesterol, a modulator of membrane-associated Aβ-fibrillogenesis and neurotoxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 311(4), 723–734. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.2001.4881 (2001).

Jakubec, M., Bariås, E., Kryuchkov, F., Hjørnevik, L. V. & Halskau, Ø. Fast and quantitative phospholipidomic analysis of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell cultures using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry and 31p nuclear magnetic resonance. ACS Omega. 4(25), 21596–21603. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b03463 (2019).

Barnes, G.& Gentle. I. Interfacial Science: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA (2011)

Gaines, G. L. Insoluble Monolayers at Liquid–Gas Interfaces (Interscience, 1966).

Butt, H., Graf, K. & Kappl, M. Physics and Chemistry of Interfaces (Wiley-VCH Verlag & Co. KGaA, 2003).

Zbinden, G. & Flury-Roversi, M. Significance of the LD50-test for the toxicological evaluation of chemical substances. Arch. Toxicol. 47(2), 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00332351 (1981).

Ładniak, A., Jurak, M. & Wiącek, A. E. Langmuir monolayer study of phospholipid DPPC on the titanium dioxide–chitosan–hyaluronic acid subphases. Adsorption. 25, 469–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10450-019-00037-1 (2019).

Heath, D.D., Pruitt, M.A., Brenner, D.E., Rock, C.L. (2003) Curcumin in plasma and urine: quantitation by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B. Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 783(1), 287–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00714-6

Den Hartogh, D. J., Gabriel, A. & Tsiani, E. Antidiabetic properties of curcumin I: Evidence from in vitro studies. Nutrients 12(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010118 (2020).

Lao, C. D. et al. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 6(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-6-10 (2006).

Yallapu, M. M., Nagesh, P. K., Jaggi, M. & Chauhan, S. C. Therapeutic applications of curcumin nanoformulations. AAPS J. 17(6), 1341–1356. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-015-9811-z (2015).

Fadus, M. C., Lau, C., Bikhchandani, J. & Lynch, H. T. Curcumin: An age-old anti-inflammatory and anti-neoplastic agent. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 7(3), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.08.002 (2017).

Li, H. M. et al. Stability of anti-liver cancer efficacy by liposomes-curcumin in water solution. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs. 37(4), 286–291 (2006).

Ranjan, A. P., Mukerjee, A., Helson, L., Gupta, R. & Vishwanatha, J. K. Efficacy of liposomal curcumin in a human pancreatic tumor xenograft model: Inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis. Anticancer Res. 33(9), 3603–3609 (2013).

Saengkrit, N., Saesoo, S., Srinuanchai, W., Phunpee, S. & Ruktanonchai, U. R. Influence of curcumin-loaded cationic liposome on anticancer activity for cervical cancer therapy. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces. 114, 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.10.005 (2014).

Feng, T., Wei, Y., Lee, R. J. & Zhao, L. Liposomal curcumin and its application in cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 12, 6027. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S132434 (2017).

Jung, S. et al. Innovative liposomes as a transfollicular drug delivery system: Penetration into porcine hair follicles. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126(8), 1728–1732. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700323 (2006).

Friedrich, R. B. et al. Skin penetration behavior of lipid-core nanocapsules for simultaneous delivery of resveratrol and curcumin. Eur. J. Pharma. Sci. 78, 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2015.07.018 (2015).

Ganesan, P. & Choi, D. K. Current application of phytocompound-based nanocosmeceuticals for beauty and skin therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 11, 1987. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S104701 (2016).

Rafiee, Z., Nejatian, M., Daeihamed, M. & Jafari, S. M. Application of curcumin-loaded nanocarriers for food, drug and cosmetic purposes. Trends Food. Sci. Technol. 88, 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2019.04.017 (2019).

Ben-Zichri, S. et al. Cardiolipin mediates curcumin interactions with mitochondrial membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1861, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.10.016 (2019).

Carpenter, T. S. et al. A method to predict blood–brain barrier permeability of drug-like compounds using molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 107, 630–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.024 (2014).

Ulander, J. & Haymet, A. Permeation across hydrated DPPC lipid bilayers: Simulation of the titrable amphiphilic drug valproic acid. Biophys. J. 85, 3475–3484. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74768-7 (2003).

Khakbaz, P. & Klauda, J. Probing the importance of lipid diversity in cell membranes via molecular simulation. Chem. Phys. Lipids 192, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2015.08.003 (2015).

Wan, G., Dai, X., Yin, Q., Shi, X. & Qiao, Y. Interaction of menthol with mixed-lipid bilayer of stratum corneum: A coarsegrained simulation study. J. Mol. Graphics. Modell. 60, 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmgm.2015.06.005 (2015).

Duda, M., Cygan, K. & Wisniewska-Becker, A. Effects of curcumin on lipid membranes: An EPR spin-label study. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 78, 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-020-00906-5 (2020).

Van Meerloo, J., Kaspers, G. J. L. & Cloos, J. Cell sensitivity assays: The MTT assay. Cancer Cell Culture. 237, 245. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-61779-080-5_20 (2011).

Syng-Ai, C., Kumari, A. L. & Khar, A. Effect of curcumin on normal and tumor cells: Role of glutathione and bcl-2. Mol. Cancer Ther. 3, 1101–1108. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.1101.3.9 (2004).

Atsumi, T., Fujisawa, S. & Tonosaki, K. Relationship between intracellular ROS production and membrane mobility in curcumin- and tetrahydrocurcumin-treated human gingival fibroblasts and human submandibular gland carcinoma cells. Oral Dis. 11, 236–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01067.x (2005).

Yoshino, M. et al. Prooxidant activity of curcumin: copper-dependent formation of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine in DNA and induction of apoptotic cell death. Toxicol In Vitro 18(6), 783–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2004.03.009 (2004).

Chen, J.W., D. Zhang, Liu, Q., Kang, J. Water-soluble antioxidants improve the antioxidant and anticancer activity of low concentrations of curcumin in human leukemia cells. Pharmazie 60, 57–61 (2005)

Fang, J., Lu, J. & Holmgren, A. Thioredoxin reductase is irreversibly modified by curcumin: A novel molecular mechanism for its anticancer activity. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 25284–25290. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M414645200 (2005).

Larasati, Y. A. et al. Curcumin targets multiple enzymes involved in the ROS metabolic pathway to suppress tumor cell growth. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 2039. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20179-6 (2018).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commemrcial or not for profit section.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K.; E.R-S—conceptualization, B.K.; B.D; E.R.-S—methodology, B.K.; B.D.—software, B.K.; B.D.; E.R-S; A.B – validation, B.K.; E.R-S—writing-original draft preparation; B.K.; B.D.; E.R-S; A.B—writing-review and editing, B.K.; E.R.-S. – visualization, B.K.; B.D.; E.R-S; A.B—supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kreczmer, B., Dyba, B., Barbasz, A. et al. Curcumin’s membrane localization and disruptive effects on cellular processes - insights from neuroblastoma, leukemic cells, and Langmuir monolayers. Sci Rep 14, 16636 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67713-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67713-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

5,7-Dihydroxyflavone acts on eNOS to achieve hypotensive effects in spontaneously hypertensive rats

Scientific Reports (2025)