Abstract

We conducted a large-scale online survey in February 2023 to investigate the public’s perceptions of COVID-19 infection and fatality risks in Japan. We identified two key findings. First, univariate analysis comparing perceived and actual risk suggested overestimation and nonnegligible underestimation of COVID-19 risk. Second, multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that age, income, education levels, health status, information sources, and experiences related to COVID-19 were associated with risk perceptions. Given that risk perceptions are closely correlated with daily socioeconomic activities and well-being, it is important for policy-makers and public health experts to understand how to communicate COVID-19 risk to the public effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Risk perceptions—people’s subjective judgments about a particular threat—play a central role in how people behave1,2. In the context of a pandemic, the public’s perceptions of associated risks may impact their willingness to engage in preventive behaviors3,4, likely affecting the effectiveness of infection control measures taken by governments, such as social distancing, sanitization, and mask-wearing requirements. Therefore, understanding risk perceptions during a pandemic is crucial.

In this study, we conducted a large-scale nationally representative survey with 40,000 respondents in February 2023 to explore how Japanese people perceive the risks of COVID-19 infection and fatality. We started by asking people’s assessments of (i) the probability of being infected with COVID-19 within the next month and (ii) the subjective probability of fatality if infected within the next month. We then collected information on individual background (age, gender, education level, income level, etc.), household structure, health situation, and COVID-19-related experiences. We also asked respondents about the primary type of media (e.g. television, newspaper, internet, social networking service (SNS), or others) they used to obtain information about COVID-19. Our analysis involved two steps. In the first step, we compared perceived risks with actual risks and evaluated the extent of overestimation or underestimation. In the second step, we revealed the factors associated with the overestimation or underestimation of COVID-19 risk through multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Our results were threefold. First, we found that, overall, Japanese people tended to overestimate the risks of infection and fatality, although a nonnegligible proportion of the population underestimated these risks. Specifically, at the end of February 2023, 50.2% of respondents perceived the risk of infection to be 5% or higher, while the actual infection rate was 0.20%. A total of 29.8% of respondents reported a case fatality rate (CFR) of 5% or higher, in contrast to the actual CFR of 0.24% during the eighth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (November 2022-February 2023). At the same time, 17.7% (27.1%) of respondents perceived the risk of infection (fatality) as less than 0.001%. These findings on risk overestimation and underestimation are robust to alternative methods of eliciting subjective risk assessments.

Second, there is heterogeneity in risk perceptions across individual attributes. Regarding the perception of infection risk, our results suggest that individuals aged 60 years or older and those without a history of COVID-19 infection were less likely to perceive a very high probability of infection and more likely to perceive a very low probability. Individuals without preexisting chronic diseases were less likely to report a very high infection risk than those with preexisting chronic diseases. Regarding the perception of fatality risk, we showed that individuals without preexisting chronic diseases were less (or more) likely to have a very high (or very low) subjective assessment of fatality risk. Less educated and low-income individuals were more likely to perceive fatality risk as very high compared to their counterparts, while those who have contracted COVID-19 were less likely to do so. Our findings were consistent across different model specifications and alternative ways of asking subjective risk perceptions.

Third, we showed that information sources are associated with risk perceptions. In particular, readers of the Asahi newspaper exhibited a greater (or lower) likelihood of overestimating (or underestimating) both infection and fatality risks than those who used other sources. NHK-TV and TBS-TV viewers were more likely to overestimate fatality risk and less likely to underestimate fatality risk. In addition, Fuji-TV and Asahi-TV viewers and individuals who read the Yomiuri papers had a greater probability of overestimating fatality risk.

On the one hand, a high level of risk perception might have been a factor limiting the spread of disease because it encourages the practice of infection prevention behaviors. On the other hand, it can lead people to restrict their economic activities, potentially hindering socioeconomic recovery. Indeed, there is evidence that socioeconomic recovery from the pandemic in Japan has been relatively slow. Specifically, the real GDP level was only 99 in Japan in 2022, compared to that of 108 in the US, 102 in Germany, and 101 in the UK in 2017–20195. Japanese consumer confidence did not return to prepandemic levels, with the real consumption index being lower in April 2023 (97.9) than in January 2020 (100.5)6. School life had not normalized by spring 2023; many school events were still cancelled in 2022–2023, and more than half of the schools forced students to eat lunch silently, which may have deteriorated children’s mental health7,8. The number of marriages decreased sharply in 2020 and has not yet recovered, likely reflecting these socioeconomic conditions. Given our findings of COVID-19 risk overestimation among Japanese people, correcting the public’s misperceptions of risk might be an important task for the government in considering economic activities and infection control.

Our study is related to the following three strands of the literature. First, it aligns with a set of studies exploring how various factors are associated with COVID-19 risk perceptions in Japan9 and other countries10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Our results complement their findings that demographic factors (e.g. age, income level, and education level), personal factors (health status, COVID-19-related experiences), media sources and the behaviors regarding the use of such sources (e.g. frequency of use and trust in media) are associated with risk perceptions. The key difference between these studies and ours is that while they focused solely on subjective risk perceptions, we compared perceived risks with actual risks and evaluated the extent of risk overestimation and underestimation.

Second, our work is closely related to a few papers comparing perceived and actual risks18,19,20. These studies analyzed the relationship between subjective risks and policy views20 or conducted information provision experiments aimed at correcting beliefs about risks18,19. Similar to our study, these studies documented quantitative evidence of the overestimation of COVID-19 risk. Our work differs from theirs because we directed our attention to various factors associated with risk perceptions and because our sample was substantially larger than their samples (40,000 respondents in our survey versus less than 4,000 respondents in their surveys).

Third, our work is related to the literature analyzing the relationship between COVID-19 risk perceptions and the practice of prevention behaviors3,4,16,21,22. These previous studies emphasized that individuals are more likely to engage in social distancing and prevention behaviors—such as wearing masks, wearing rubber gloves, and handwashing—when they perceive greater risk. Our analysis differs from these studies in that we investigated factors associated with risk misperceptions (risk overestimation and underestimation).

To summarize, the originality of our paper lies in (i) the comparison of actual and perceived risks, (ii) our focus on factors associated with risk perceptions/ misperceptions, and (iii) our large sample size. In addition, our paper is unique in that we examined COVID-19 risk perceptions in the later stage of the pandemic, as opposed to the earlier stage. Accordingly, our survey can shed light on the persistence of risk misperceptions and has novel implications for risk communications.

Methods

Setting and respondents

We conducted a nationally representative cross-sectional survey in February 2023 with 40,000 respondents. We recruited survey respondents online through collaboration with a survey company (Cross Marketing, Inc.). We asked men and women aged 20 years or older about their assessment of the risks associated with COVID-19 as well as various individual attributes. The response period was from February 22 to February 27, 2023, a period when Japan was in the late stage of the eighth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. For the trend of the number of daily new cases and deaths during this period, see Fig. SI1 in the Supplementary Information (SI) Appendix. To ensure that the survey is representative of the general population, the respondents’ distributions in age, gender, and place of residence were matched to those in the 2020 Population Census in Japan. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo (22–388). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

All data used in our paper are based on the survey we conducted. Nowhere in the paper do we conduct simulations or predictions using mathematical models. There are vast literatures analyzing various aspects of COVID-19—from forecasting to scenario analysis to evaluation of past policies—using mathematical models23,24,25,26,27,28,29. In addition, there are vast literatures analyzing various issues using mathematical models in other scientific fields30,31,32,33,34. Mathematical models are a key tool for scientific inquiry in a wide range of fields. In contrast to these papers, our paper is based on the survey data only and uses widely used statistical methods to analyze the survey data.

Perception of COVID-19 risk

Our goal was to understand how people perceive the risks of COVID-19 infection and fatality and whether various individual attributes are associated with risk perceptions. To this end, we asked survey respondents to rate (1) their subjective probability of becoming infected with COVID-19 within the next month and (2) their subjective probability of fatality if infected within the next month. These questions were answered on an ordinal scale consisting of the following nine options: (1) less than 0.001%, (2) 0.001% to less than 0.01%, (3) 0.01% to less than 0.1%, (4) 0.1% to less than 1%, (5) 1% to less than 5%, (6) 5% to less than 10%, (7) 10% to less than 20%, (8) 20% to less than 50%, and (9) 50% or higher. In a follow-up survey we describe later in this paper, we considered alternative presentations of the probability options to check the robustness of the key messages of our study.

We compared the subjective probabilities with the actual probabilities of infection and fatality. To compute actual probabilities, we used (i) data on the population of Japan published by the Statistics Bureau of Japan35 and (ii) daily data on the newly confirmed cases and deaths published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare36. According to our calculation, the proportion of people with new COVID-19 infections from February 24 to March 23, 2023 (corresponding to a one-month period from the survey) accounted for 0.20% of the estimated population of Japan as of March 2023. The case fatality rate in the eighth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic—calculated as the cumulative number of deaths divided by the total number of newly infected cases from November 1, 2022, to February 28, 2023—was 0.24%.

Supplemental survey

Because we elicited subjective risk perceptions through multiple choices, one concern was that some respondents may determine that the middle option is more likely to be correct and choose it accordingly. To check whether this potential bias affects our findings, we implemented an additional survey in April 2023 involving 10,010 respondents. The age and gender distributions again were matched to those of the 2020 Population Census. In this supplementary survey, respondents were divided evenly into five groups; each group was presented with different answer options for questions about the subjective assessments of risks.

We provided group “Choice A” with the same nine options as in the original survey. Moreover, we provided seven options for groups “Choice B”, “Choice C”, and “Choice D”. Group “Choice B” was given the options of (1) less than 0.001%, (2) 0.001–0.01%, (3) 0.01–0.1%, (4) 0.1–1%, (5) 1–5%, (6) 5–10%, and (7) 10% or higher. Group “Choice C” was given the options of (1) less than 0.1%, (2) 0.1–1%, (3) 1–5%, (4) 5–10%, (5) 10–20%, (6) 20–50%, and (7) 50% or higher. Group “Choice D” was provided with the options (1) less than 0.01%, (2) 0.01–0.1%, (3) 0.1–1%, (4) 1% – 5%, (5) 5–10%, (6) 10–20%, and (7) 20% or higher. Finally, for Group “Choice E”, we asked respondents to input a specific number (in percentage) representing their assessment of the probability of infection or the CFR instead of presenting multiple answer options.

Characteristics of the survey respondents

In addition to their subjective assessment of COVID-19 risk, the main survey in February 2023 gathered information about the respondents’ various individual characteristics. We collected basic information, including age, gender, place of residence (up to municipality level), education level, and income class. To understand the household structure, we also asked whether the respondents were living with (i) a spouse or partner, (ii) family members older than 65 years, (iii) a child attending college or high school, (iv) a child attending junior high school, (v) a child attending elementary school, and/or (vi) a child attending preschool or an infant. We also inquired about their smoking habits and medical history. For medical history, we asked if the respondents had any of the following chronic diseases: (1) malignant neoplasms (cancer), (2) cerebrovascular diseases (e.g. cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral infarction), (3) respiratory system diseases, (4) cardiovascular diseases (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction), (5) gastrointestinal diseases (e.g. stomach, intestine, liver, spleen diseases), (6) endocrine system diseases (e.g. diabetes), (7) kidney diseases, or (8) hematological diseases (e.g. anemia). Additionally, we asked about COVID-19-related information, including the vaccination status, the number of previous infections, and whether the respondents had any acquaintances—such as family members, relatives, or friends—who died from the virus.

Finally, we asked respondents which type of media (television, newspaper, internet, SNS, or others) was their primary source of information about COVID-19 to examine whether the content and tone of COVID-19 reports are associated with people’s overall assessment of COVID-19 risk. For respondents who primarily relied on TVs, we asked about which TV channels they preferred to watch the most (NHK, Nihon, Fuji, TBS, Tokyo, Asahi, or others). For those who primarily read newspapers, we asked about which newspaper they preferred to read (the Asahi, Mainichi, Yomiuri, Sankei, Nikkei, or others). For those who relied on SNS, we inquired about which platform they used the most (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, or others).

Statistical analysis

We applied logistic regression analyses to examine the relationships between the respondents’ individual characteristics and subjective assessments of COVID-19 risk.

For the outcome variables, we utilized the respondents’ answers regarding infection (or fatality) risk to generate proxies for risk overestimation and underestimation. Specifically, the proxies for risk overestimation were infection (fatality) risk over 1%, infection (fatality) risk over 5%, and infection (fatality) risk over 10%, which were assigned a value of one if the subjective risk of infection (or fatality) was equal to or greater than 1%, 5%, or 10%, respectively, and zero otherwise. Proxies of risk underestimation were infection (fatality) risk under 0.001%, infection (fatality) risk under 0.01%, and infection (fatality) risk under 0.1%, which were assigned a value of one if the subjective risk of infection (or fatality) was less than 0.001%, 0.01%, or 0.1%, respectively, and zero otherwise.

For the independent and control variables, we used information on respondent attributes from the survey. The independent variables included college graduate, which equals one if the person has a bachelor’s degree or higher, and high income, which equals one if the person has an income including taxes and bonuses in 2022 from 4 million yen (median) or more. The independent variables further included age group, gender, household structure, vaccination status, health situation (represented by the dummy variables smoker and no chronic diseases), proxies for COVID-19-related experiences (infected with COVID-19 and acquaintances who died from COVID-19), and the primary media source to which the respondents referred. We controlled for respondents’ residences via prefecture fixed effects to account for potential variations in the extent of COVID-19 spread and mitigation measures across prefectures. The analyses were conducted using Stata version 17 (College Station, TX, USA), and two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Respondent characteristics

Table 1 displays the respondents’ characteristics, their corresponding answer options, and the number and percentage of respondents for each option. The groups aged 40–59 years and over 60 years accounted for the largest proportion of respondents, comprising 33.5% and 42.1% of the total, respectively. Male respondents accounted for 48.0% of the sample. A total of 42.9% of the respondents had a college degree or higher, raising the potential concern that the level of educational attainment among the surveyed population was relatively higher than that of the general population (25.7% according to the 2020 Population Census data). For income level, a significant proportion of respondents fell within the range of 2–4 million yen (26.7%). In terms of household composition, the majority of respondents lived with a spouse or partner (59.8%), while some lived with elderly family members (21.3%) aged 65 years or older or with children (19.8%).

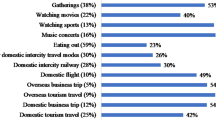

Regarding vaccination status, 75.5% of the respondents reported that they had received three or more vaccine doses. For information on the respondents’ health situations and experiences related to COVID-19, 17.2% had smoking habits, 15.6% had chronic diseases, 22.5% had a history of COVID-19 infection, and 3.9% had acquaintances who died from COVID-19. Finally, the most important source of information on COVID-19 was TVs (43.6%), followed by the internet (36.7%).

Univariate analysis

Figure 1 shows the distributions of subjective infection risk (Fig. 1a) and fatality risk (Fig. 1b). In the figure, the blue vertical lines represent the statistics on subjective risk (sample mean and median), whereas the red vertical lines represent the actual risk.

As illustrated in Fig. 1a, many respondents assessed the infection risk as being much greater than the actual infection risk of 0.20%. Among all respondents, 50.2% (16.9 + 14.5 + 12.8 + 6.1) believed that their likelihood of contracting COVID-19 within the next month was 5% or greater. Setting a higher threshold, we find that 33.3% (14.5 + 12.8 + 6.1) of the respondents assessed the infection risk as 10% or higher. Nevertheless, a nonnegligible proportion of the respondents underestimated the infection risk, with 17.7% considering the infection risk to be almost zero (less than 0.001%).

Figure 1b shows that the respondents tended to overestimate the CFR compared to the actual rate (0.24% during the period from November 2022 to February 2023). Specifically, 29.8% (19.1%) of the respondents reported a subjective fatality risk of more than 5% (10%), with 9.9% choosing the 5–10% option, 7.8% choosing 10–20%, 7.0% choosing 20–50%, and 5.1% choosing more than 50%. On the other hand, a significant proportion of respondents underestimated the CFR, with 27.1% perceiving it as less than 0.001%.

We checked the robustness of these findings using alternative answers. Tables SI1 and SI2 in the SI Appendix compare the proportions of respondents who overestimated or underestimated COVID-19 risk in the original and supplementary surveys, respectively. Even with the modified answer options, many respondents overestimated the infection and fatality risks, and a nonnegligible number underestimated these risks. Table SI1 shows that 69% (47%) of the respondents in the original survey assessed the risk of infection (fatality) as being above 1%, whereas in the supplementary survey, the proportion ranged from 51 to 79% (28% to 66%). Moreover, Table SI2 shows that 21% (40%) of the respondents in the original survey perceived the infection (fatality) risk as being less than 0.1%, compared to 20 to 30% (32 to 52%) in the supplementary survey.

Given that the risks of infection and fatality depend on age, in Table 2, we show the degree of risk overestimation and underestimation for the three age groups. As shown in Table 2a, the actual infection rates during the survey periods were 0.261%, 0.209%, and 0.148% for the groups aged “20–39”, “40–59”, and “over 60” years, respectively. The majority of the respondents in all age groups overestimated the infection risk, especially young persons aged 20 to 39 years, with 40% reporting an infection rate above 10%. However, in all three age groups, 17–18% of the respondents reported that the subjective infection rate was less than 0.001%, suggesting that a certain proportion of Japanese people underestimate the infection risk regardless of age.

For the case fatality rate, Table 2b shows that the actual rate was approximately 1% for those aged 60 years and over, whereas it was much lower for those aged 40–59 years and those aged 20–39 years (0.015% and 0.002%, respectively). The proportions of respondents who overestimated and underestimated the risk in the group aged “20–39” years were almost the same as those in the group aged “40–59” years. However, the proportion of respondents who overestimated (or underestimated) the risk of fatality was considerably greater (or lower) in the group aged “over 60” years than in the other groups.

Multivariate analysis

Figure 2 presents the results of the logistic regression analyses on the overestimation and underestimation of infection risk, using infection risk over 1%, 5%, and 10% and infection risk under 0.001%, 0.01%, and 0.1%, respectively, as dependent variables. In all figures presenting logistic regression results, the odds ratios for prefecture fixed effects are omitted for simplicity. The analysis revealed that several factors are associated with perceptions of infection risk.

Factors associated with perceived COVID-19 infection risk. Odds ratios and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals are presented on the right-hand side of the figures. N = 40,000. Alternative specifications of the estimations are shown in SI Appendix Fig. SI7.

First, as shown at the top of Fig. 2a and b, demographic factors (education level, income level, age, and gender) were associated with the perception of infection risk. Specifically, when utilizing proxies for very high perceptions of risk (Fig. 2a) and very low perceptions of risk (Fig. 2b), the odds ratios for the variables college graduates and high income were lower than 1 and statistically significant in most cases. That is, college graduates and high-income individuals were less likely to assess their infection risk as very high or very low. Moreover, age was associated with a lower assessment of infection risk, as indicated by the lower (or higher) probability of perceiving such risk as very high (or very low). Regarding gender, the results showed that females perceived the threat of COVID-19 infection to be greater than males did.

Second, household structure was correlated with the perception of infection risk. In particular, the evidence indicated that individuals living with (i) a spouse or partner, (ii) elderly family members, and/or (iii) children were more (or less) likely to perceive a very high (or very low) infection risk, possibly due to close household contact.

Third, the assessment of infection risk was also associated with factors such as health situation, vaccination status, and experiences related to COVID-19. The following groups of respondents had a greater (or lower) probability of perceiving the infection risk as being very high (or very low): (i) smokers, (ii) people with chronic health conditions, (iii) individuals who had received at least three vaccine doses, and (iv) individuals who had contracted COVID-19 themselves or lost acquaintance(s)—such as family members, relatives, or friends—to the virus.

Finally, as shown at the bottom of Fig. 2a and b, media preferences tended to be associated with subjective assessments of infection risk. We found that Asahi newspaper readers were more (or less) likely to overestimate (or underestimate) infection risk than internet users (the base category). In addition, individuals who used Nihon-TV, Fuji-TV, or TikTok as their primary source of information about COVID-19 were more likely to underestimate infection risk than others were.

Regarding the perceptions of fatality risk, Fig. 3 displays the results from logistic regressions with the outcome variables fatality risk over 1%, 5%, and 10% and fatality risk under 0.001%, 0.01%, and 0.1%, respectively.

As shown at the top of the figures, individuals with higher educational attainment and higher income levels were less (or more) likely to report a very high (or very low) subjective fatality risk. Individuals aged 60 years or older were more (or less) likely to report a very high (or very low) subjective fatality risk than individuals in younger age groups, a finding consistent with the fact that older people face a substantially greater risk of fatality once infected with COVID-19 than younger people.

Moreover, the following factors—being female, living with elderly individuals, receiving three vaccine doses, smoking, having a poor health status, and knowing someone who died from COVID-19—were associated with a greater assessment of fatality risk. Moreover, individuals with a history of COVID-19 infection were less (or more) likely to report a very high (or very low) fatality risk. This finding could be rationalized if these individuals felt, through their own experiences, that COVID-19 was not as severe as they had imagined prior to infection.

Finally, Fig. 3 demonstrates that information sources played a critical role in people’s assessments of fatality risk related to COVID-19. As shown in the left figure, viewers of major television channels in Japan (NHK, Nihon, Fuji, TBS, and Asahi) and readers of three newspapers (Asahi, Yomiuri, and Sankei) were more likely to overestimate fatality risk than were those who obtained COVID-19 information mainly from the internet. Moreover, as indicated in the right figure, viewers of NHK TV and TBS TV and readers of the Asahi newspaper were less likely to underestimate fatality risk. Twitter users were more likely to underestimate fatality risk, but overall, we did not find a statistically significant difference between fatality risk assessments of internet users and users of social media platforms.

Robustness check

We took three approaches to test the robustness of the results presented in the preceding subsection (Multivariate Analysis). The first approach was performing logistic regression analyses using data from the supplemental survey, in which we elicited risk assessments in various ways. Specifically, for five subsamples (“Choice A”—“Choice E”), we regressed proxies for overestimation and underestimation of infection (or fatality) risk on individual characteristics (demographics, health status, personal experiences related to COVID-19) and primary media source (television, newspaper, internet, SNS, or others). We also controlled for regional fixed effects. The results are shown in SI Appendix Figs. SI2 and SI3.

The second approach was employing a linear regression model instead of a logistic regression model. In this analysis, the continuous outcome variables—probability of infection and probability of fatality—were the midpoints in responses about subjective risks. For example, if a respondent perceived the infection risk as 50% or higher, the probability of infection was 75%. If he or she assessed the risk to be between 20 and 50%, the variable was assigned a value of 35%. We used the same set of independent variables as in the logistic regression model. SI Appendix Figs. SI4 and SI5 present the results from the linear regressions using data from our main and supplemental surveys.

The third approach was using an alternative set of outcome variables in the baseline analysis. In the baseline analysis, we utilized infection (fatality) risk over 1%, 5%, and 10% as proxies for risk overestimation (see Figs. 2a and 3a). Here, we reran the logistic regressions using infection (fatality) risk over 5%, 10%, and 20% as outcome variables. We provide the results for the main survey in SI Appendix Fig. SI6 and the supplemental survey in SI Appendix Fig. SI7.

As indicated in SI Appendix Figs. SI2 to SI7, the following findings are robust to alternative methods of eliciting subjective risks and various model specifications. In terms of the subjective infection risk, the evidence suggests that individuals aged 60 years or older are less (or more) likely to assess their infection risk as very high (or very low) compared to others. Moreover, individuals who have previously contracted COVID-19 are more (or less) likely to assess such risk as very high (or very low). Individuals without preexisting chronic diseases are less likely to report a very high infection risk. In addition, readers of the Asahi newspaper are more (or less) likely to report a very high (or very low) infection risk than individuals who use other information sources.

In terms of the subjective fatality risk, we found that individuals without preexisting chronic diseases are less (or more) likely to have a very high (or very low) assessment of fatality risk. Less educated and low-income individuals are more likely to report a very high fatality risk. People who have contracted COVID-19 are less likely to perceive such risk as very high. Moreover, viewers of NHK-TV and TBS-TV and readers of the Asahi newspaper are more (or less) likely to report a very high (or very low) fatality risk. Viewers of Fuji-TV and Asahi-TV and readers of the Yomiuri newspaper are more likely to report a very high fatality risk than individuals who use other information sources.

Discussion

We propose two ways to to improve the communication of risks during the COVID-19 pandemic based on our research.

First, in light of our findings that risk misperceptions exist among Japanese people and that information sources are associated with risk perceptions, it might be helpful for the government to promote regular dissemination of accurate and timely information about COVID-19 risks to the Japanese population. Improved information provision by the government is a particularly important consideration in light of risk communication in Japan. In fact, there have been delays in COVID-19 risk estimations by experts advising Japanese policymakers37. In particular, the CFR was often updated approximately 4–5 months later by the New Coronavirus Infectious Disease Control Headquarters—the key government council that determined general policies regarding COVID-19. As the CFR substantially declined in early 2022 due to the change in the COVID-19 variant (from the Delta to Omicron variant) and widespread vaccination, such a delay in CFR updates may have influenced the general public’s willingness to normalize their lives, thus affecting Japan’s socioeconomic recovery from the pandemic.

Given this situation, the government may consider incorporating statistical data and/or accompanying simulation scenarios to enhance the correct understanding of risks and better communicate COVID-19-related risk information. Studies on information provision have shown that people adjust their existing beliefs about COVID-19 in response to expert information19, and the combination of statistics and episodic simulations can facilitate effective information communication38,39. For example, an earlier study demonstrated that by asking respondents to estimate the risks of infection in hypothetical scenarios (such as in a restaurant with 25 people or at a party with 100 people) before giving them feedback on the actual risks, more significant changes in the risk perceptions and behaviors of respondents can be observed39.

Second, considering our finding that individuals with different characteristics (age, socioeconomic status, health conditions, and history of COVID-19 infection) have different subjective assessments of infection and fatality risk, group-specific risk communication could be effective. For example, our results suggested that individuals with low income or low education are more likely to report that the fatality risk is very high. The government may consider disseminating risk information to these specific groups in more intuitive and more easily understandable ways than they did during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interpersonal communication can also play a major role in altering people’s risk perceptions40,41,42. Therefore, it might be a good idea for the government to consider organizing discussions and dialogs involving experts and scientists to help people adjust their perceptions of COVID-19 risk.

Conclusion

Our large-scale survey provided several new insights into COVID-19 risk perceptions. First, when comparing perceived risks with actual risks, we found that the majority of respondents overestimated the infection and fatality risks, regardless of age. Second, we nevertheless found that a proportion of respondents underestimated such risks. Third, there is heterogeneity in risk perceptions across individual characteristics, including age groups, socioeconomic status, health conditions, and history of COVID-19 infection. Finally, our findings highlight that it is important to understand the role of information sources in improving communication about public health policy between governments and the public.

In future research, it would be interesting to examine what kinds of communications are effective in correcting the public’s risk misperception. It would be also interesting to analyze the degree of risk misperceptions regarding other diseases and explore the extent to which such risk misperceptions may contribute to inefficiency in the allocation of medical resources. Finally, it would be interesting to explore whether risk perceptions have any long-run implications for individual’s health outcomes.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are not readily available due to consent agreements for data security as well as IRB approval. Requests to access the data should be directed to Taisuke Nakata (taisuke.nakata@e.u-tokyo.ac.jp).

References

Brewer, N. T. et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 26, 136–145 (2007).

Ferrer, R. A. & Klein, W. M. P. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 5, 85–89 (2015).

Bruine De Bruin, W. & Bennett, D. Relationships between initial COVID-19 risk perceptions and protective health behaviors: A national survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 59, 157–167 (2020).

Sato, M., Kinoshita, S. & Ida, T. Subjective risk valuation and behavioral change: Evidence from COVID-19 in the U.K. and Japan. Discussion Paper No. E-22-011, Graduate School of Economics, Kyoto University. http://www.econ.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dp/papers/e-22-011.pdf (2022).

International Monetary Fund. World economic outlook. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/datasets/WEO (Accessed on April 2023) (2023).

Bank of Japan. Consumption activity index. https://www.boj.or.jp/en/research/research_data/cai/index.htm (2023).

Shobako, N. Lessons from the health policies for children during the pandemic in Japan. Front. Public Health 10, 1015955. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1015955 (2022).

Takaku, R., Shobako, N. & Nakata, T. Three years of COVID-19-related school restrictions and children’s mental health in Japan. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3144141/v1 (2023).

Adachi, M. et al. Factors associated with the risk perception of COVID-19 infection and severe illness: A cross-sectional study in Japan. SSM Popul. Health 18, 101105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101105 (2022).

Cipolletta, S., Andreghetti, G. R. & Mioni, G. Risk perception towards COVID-19: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084649 (2022).

Dryhurst, S. et al. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 23, 994–1006 (2020).

Dyer, M. L., Sallis, H. M., Khouja, J. N., Dryhurst, S. & Munafò, M. R. Associations between COVID-19 risk perceptions and mental health, wellbeing, and risk behaviours. J. Risk Res. 25, 1372–1394 (2022).

Gollust, S. E. et al. Americans’ perceptions of disparities in COVID-19 mortality: Results from a nationally-representative survey. Prev. Med. 141, 106278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106278 (2020).

Huynh, T. L. D. The COVID-19 risk perception: A survey on socioeconomics and media attention. Econ. Bull. 40, 758–764 (2020).

Vai, B. et al. Risk perception and media in shaping protective behaviors: Insights from the early phase of COVID-19 Italian outbreak. Front. Psychol. 11, 563426. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.563426 (2020).

Savadori, L. & Lauriola, M. Risk perceptions and COVID-19 protective behaviors: A two-wave longitudinal study of epidemic and post-epidemic periods. Soc. Sci. Med. 301, 114949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114949 (2022).

Wise, T., Zbozinek, T. D., Michelini, G., Hagan, C. C. & Mobbs, D. Changes in risk perception and self-reported protective behaviour during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 200742. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200742 (2020).

Abel, M., Byker, T. & Carpenter, J. Socially optimal mistakes? Debiasing COVID-19 mortality risk perceptions and prosocial behavior. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 183, 456–480 (2021).

Akesson, J., Ashworth-Hayes, S., Hahn, R., Metcalfe, R. & Rasooly, I. Fatalism, beliefs, and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Risk Uncertain. 64, 147–190 (2022).

Graso, M. The new normal: Covid-19 risk perceptions and support for continuing restrictions past vaccinations. PLoS One 17(4), e0266602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266602 (2022).

Bundorf, M. K. et al. Risk perceptions and private protective behaviors: Evidence from COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Econ. Stat. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01309 (2023).

Garfin, D. R., Fischhoff, B., Holman, E. A. & Silver, R. C. Risk perceptions and health behaviors as COVID-19 emerged in the United States: Results from a probability-based nationally representative sample. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 27, 584–598 (2021).

Fujii, D. & Nakata, T. COVID-19 and output in Japan. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 72, 609–650 (2021).

Fujii, D., Nakata, T. & Ojima, T. Heterogeneous risk attitudes and waves of infection. PLoS One 19, e0299813 (2024).

Kodera, S., Ueta, H., Unemi, T., Nakata, T. & Hirata, A. Population-level immunity for transient suppression of COVID-19 waves in Japan from April 2021 to September 2022. Vaccines 11, 1457 (2023).

Kuniya, T., Nakata, T. & Fujii, D. Optimal vaccine allocation strategy: Theory and application to the early stage of COVID-19 in Japan. Math. Biosci. Eng. 21, 6359–6371 (2024).

Ouncharoen, R. et al. Study of integer and fractional order COVID-19 mathematical model. Fractals 31, 2340046 (2023).

Ahmad, S. W., Sarwar, M., Shah, K., Ahmadian, A. & Salahshour, S. Fractional order mathematical modeling of novel corona virus (COVID-19). Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 46, 7847–7860 (2023).

Sinan, M., Shah, K., Abdeljawad, T. & Akgul, A. Analysis of nonlinear mathematical model of COVID-19 via fractional-order piecewise derivative. Chaos Theory Appl. 5, 27–33 (2023).

Mondal, B., Thirthar, A. A., Sk, N., Alqudah, M. A. & Abdeljawad, T. Complex dynamics in a two species system with Crowley–Martin response function: Role of cooperation, additional food and seasonal perturbations. Math. Comput. Simul. 221, 415–434 (2024).

Pakhira, R., Mondal, B., Thirthar, A. A., Alqudah, M. A. & Abdeljawad, T. Developing a fuzzy logic-based carbon emission cost-incorporated inventory model with memory effects. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15, 102746 (2024).

Thirthar, A. A. A mathematical modelling of a plant-herbivore community with additional effects of food on the environment. Iraqi J. Sci. 64, 3551–3566 (2023).

Thirthar, A. A., Jawad, S., Majeed, S. J. & Nisar, K. S. Impact of wind flow and global warming in the dynamics of prey–predator model. Results Control Optim. 15, 100424 (2024).

Thirthar, A. A., Sk, N., Mondal, B., Alqudah, M. A. & Abdeljawad, T. Utilizing memory effects to enhance resilience in disease-driven prey-predator systems under the influence of global warming. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 69, 4617–4643 (2023).

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Population estimates. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/ (2023).

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Visualizing the data: Information on COVID-19 infections. https://covid19.mhlw.go.jp/en/ (2023).

Ohtake, F. & Kobayashi, K. Opinion on data on new coronavirus infections. https://note.com/fohtake/n/n88f5ba75f30f (2022).

Allen, M. et al. Testing the persuasiveness of evidence: Combining narrative and statistical forms. Commun. Res. Rep. 17, 331–336 (2000).

Sinclair, A. H., Hakimi, S., Stanley, M. L., Adcock, R. A. & Samanez-Larkin, G. R. Pairing facts with imagined consequences improves pandemic-related risk perception. PNAS 118, e2100970118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2100970118 (2021).

Binder, A. R., Scheufele, D. A., Brossard, D. & Gunther, A. C. Interpersonal amplification of risk? Citizen discussions and their impact on perceptions of risks and benefits of a biological research facility. Risk Anal. 31, 324–334 (2011).

Kasperson, R. E. et al. The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Anal. 8, 177–187 (1988).

Kasperson, R. E., Webler, T., Ram, B. & Sutton, J. The social amplification of risk framework: New perspectives. Risk Anal. 42, 1367–1380 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of the conference on COVID-19 policies held by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and the Tokyo Center for Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding

This study was supported by the "COVID-19 AI & Simulation Project" (run by the Mitsubishi Research Institute commissioned by the Cabinet Secretariat of Japan), a JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI), Project Number 22H04927, the Research Institute of Science and Technology for Society at the Japan Science and Technology Agency, and the Center for Advanced Research in Finance at the University of Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: TN, RT, and AC. Data curation: RT, AC, and TLN. Formal analysis: RT and TLN. Investigation: RT and TN. Methodology: RT and TN. Project administration: TN. Supervision: TN and RT. Visualization: RT and TLN. Writing—original draft: RT and TLN. Writing—review & editing: TN, RT, and TLN. All authors have read and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chiba, A., Nakata, T., Nguyen, T.L. et al. COVID-19 risk perceptions in Japan: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 14, 16862 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67741-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67741-z