Abstract

In order to study the damage properties of red sandstone under combined action of temperature, water and stress, the uniaxial compression test was carried out for red sandstone after immersing in water for 0.5 h, 1 h and 3 h at 25 ℃, 55 ℃, 85 ℃ and 95 ℃, the mechanical properties, characteristic stress points, acoustic emission RA-AF parameters and failure forms of red sandstone were analyzed, the damage constitutive equation was established, and the damage properties of red sandstone were studied. The results showed: (1) temperature could significantly improve the saturated water content percentage of red sandstone. With the increase of temperature, the saturated water content percentage showed a trend of increase first and then decrease, and was the largest at 55 ℃; with the increase of temperature, the mechanical parameters (peak intensity, elasticity modulus, and stress at start point of expansion) decreased first and then increased, and was the smallest at 55 ℃; (2) the ratio of crack initiation stress to peak stress (σci/σf) initially increases and then decreases with rising temperatures for the same soaking duration. Conversely, it initially decreases and then increases with extended soaking time at the same temperature. The RA-AF acoustic emission signals predominantly occur in the tensile region at each stage account for a relatively large proportion, with the proportion of signals in the shear region significantly increasing as soaking time extends, corresponding well with the observed damage patterns. (3) By considering the damage due to temperature and water as Initial damage to red sandstone and the damage due to stress as load-induced damage, a damage variable based on the Weibull distribution function was established. The comprehensive damage constitutive equation derived from this can be applied to water-saturated red sandstone below 100 ℃. The findings provide theoretical reference for practical engineering applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, in order to meet energy demands and improve transportation convenience, the construction of deep underground engineering projects has gained increasing attention. However, various geological hazards frequently arise during such projects. In environments with high temperatures and high stress levels, surrounding rock masses are prone to instability, compromising construction progress and safety. In water-rich environments, the weakening effect of water on rocks and the influence of pore water pressure make rock masses more susceptible to instability during construction1,2. Therefore, the study of rock damage and failure characteristics under the combined effects of temperature, water, and stress holds significant importance.

In practical engineering, the combined or pairwise effects of stress, temperature, and water on underground rock masses are pervasive. Numerous researchers have extensively studied the patterns of rock damage and failure under these three influencing factors.

Under hydro-mechanical coupling, Zhang focused on water inrush hazards from coal seam floors, conducted seepage experiments on single-fracture, T-shaped, and Y-shaped fractured rock samples3. The experiments explored non-linear seepage patterns and used acoustic emission monitoring to investigate the progressive failure evolution mechanism in fractured rock masses. However, the inherent randomness of rock fractures hindered a comprehensive understanding of hydro-mechanical coupling mechanisms. Bian et al.4 performed uniaxial compression tests on shale samples subjected to various immersion periods, deriving a constitutive equation suitable for weak water effects and uniaxial compression. In thermo-mechanical coupling studies, Long conducted uniaxial compression tests on sandstone at various temperatures and triaxial compression tests at varying temperatures and confining pressures5. The results showed that temperature enhances sample deformability to some extent, and that rising temperatures both weaken and strengthen sandstone’s mechanical properties. Guo et al.6 conducted uniaxial compression experiments on granite at temperatures ranging from 25 to 600 °C and established a constitutive equation based on thermal damage theory. Nevertheless, practical engineering conditions rarely feature complete coupling of water force or temperature force. More often, engineering projects encounter the combined effects of temperature, water, and stress.

To investigate rock damage characteristics under the combined effects of temperature, water, and stress, Liu et al.7 conducted uniaxial compression tests on argillaceous siltstone samples soaked in varying water temperatures until saturation. They explored the effects of water and temperature on rock mechanical properties from both a macroscopic and microscopic perspective using SEM images but did not quantify the influence of each factor. Gao et al., conducted uniaxial compression tests on sandstone under thermo-hydro-mechanical coupling conditions, investigating the effects of various influencing factors on the rock. It was found that stress had the greatest impact on Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and peak strength, while temperature had the least8. Building on this, Lu et al., performed a series of water absorption and uniaxial compression tests on mudstone and sandstone soaked at varying temperatures and employed CT scanning to analyze their microstructure. The results indicated that the rise in water temperature increased the formation of new internal cracks, intensifying water-induced damage9. Xu et al.10 seeked to understand the effect of high temperatures on the permeability of argillaceous sandstone, conducted triaxial compression tests, which proved that mechanical parameters are not highly sensitive to water temperature. The main mechanism casing the permeability is due to the thermal expansion of illite, which clogs internal pores. Long improved the Duncan-Chang model and derived a three-field control model, establishing a constitutive equation for sandstone under the combined effects of temperature, seepage, and load5.

From the above studies, it is evident that most research on the damage characteristics of rocks under the combined effects of temperature, water, and stress has focused on high temperatures (above 100 °C). However, many underground engineering projects is below 100 ℃. As a result, research on the damage and failure characteristics of rocks at practical conditions (below 100 °C), including temperature, water, and stress, remains scarce. Therefore, this paper first conducts immersion tests on red sandstone in various water temperatures below 100 °C, followed by uniaxial compression tests to analyze its mechanical properties, acoustic emission RA-AF parameters, and failure morphology. Based on the findings, the damage to red sandstone is classified into initial and load damage, and a damage constitutive equation applicable to saturated red sandstone below 100 °C is established.

Uniaxial compression test under the combined action of temperature and water

Rock sample preparation and testing scheme

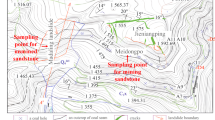

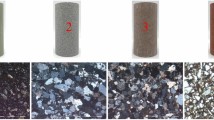

The rock samples used are composed of red sandstone (22.7% quartz, 77.3% feldspar) in cylindrical form with dimensions of Ø 50 mm × 100 mm. Prior to the experiment, the specimens were allowed to naturally air-dry indoors for over a week. They were then placed in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h for further drying11. After cooling to room temperature, strain gauges were attached in both vertical and horizontal orientations, as shown in Fig. 1.

Experimental system and process. (a) Electric thermostatic drying oven; (b) electric thermostatic water bath; (c) WAW-1000B electro-hydraulic servo universal testing machine; (d) loading test setup; (e) AEwin Express8 acoustic emission system; (f) Donghua DH3820 stress–strain acquisition system. (I) Strain gauge; (II) Spoke-type stress sensor; (III) insulated device; (IV) acoustic emission preamplifier; (V) nano sensor (acoustic emission probe).

Given that water content greatly influences various mechanical properties of rocks, According to literature9,12, red sandstone reaches a saturated state after being submerged for 3 h. High temperatures intensify molecular activity between water and rock materials, thereby enhancing the water absorption effect of rock minerals. Consequently, the soaking durations were set to three gradients: 0.5 h, 1 h, and 3 h. During tunnel construction, tunnels with surrounding rock temperatures exceeding 30 °C are referred to as high-temperature tunnels. Currently, the highest surrounding rock temperature encountered domestically is 88.8 °C in the Nigou Tunnel13. To consider normal temperature (25 °C), the highest temperature (88.8 °C), and not exceeding 100 °C, temperature gradients were set at 25 °C, 55 °C, 85 °C, and 95 °C. The specific test plan is outlined in Table 1.

Experimental groups 1–12 underwent uniaxial compression tests after soaking. To investigate the variation in water content of red sandstone, additional soaking test groups 13–20 were introduced, with soaking durations of 3.5 h and 4 h at various temperatures (25 °C, 55 °C, 85 °C, 95 °C). It was concluded that the specimens reached a nearly saturated state after 3 h.

Testing equipment and procedure

The specimens are weighed after immersion in water at different temperatures and put into the heat preservation device (internal paste thermostatic heating device), and the device is placed on the test bench to carry out the loading test, and at the same time, the acoustic emission system is used for real-time monitoring. The loading system uses WAW-1000B electro-hydraulic servo-electric universal testing machine; the acoustic emission acquisition device features a precision of 16 bits, A/D sampling rate of 10 MHz, bandwidth ranging from 1 to 1.2 kHz, threshold value of 40 dB, and the preamplifier is set at 40 dB. The test system as well as the test flow are illusrated in Fig. 1.

Experimental results and analysis

Characteristics of water content variation in red sandstone at various temperatures

To investigate the influence of varying temperatures on the water absorption properties of red sandstone, soaking tests were conducted on the red sandstone samples at various temperatures and soaking durations. The test results are presented in Fig. 2.

As seen in Fig. 2, the water content of red sandstone increases with soaking time before eventually stabilizing. Specifically, after soaking for 0.5 and 1 h, the water content across all temperature conditions is relatively similar. After 3 h, the water content rises significantly and approaches saturation11,12. At the 3.5-h and 4-h marks, water content remains largely unchanged. Meanwhile, the water content of red sandstone at 55 °C, 85 °C, and 95 °C is notably higher than that at 25 °C, indicating that increasing the soaking temperature effectively raises the water content of red sandstone. However, the relationship between temperature and water absorption is not linear. This is because, when temperatures exceed 25 °C, the increased molecular activity of water allows it to penetrate the rock’s micropores and microcracks more easily, while higher temperatures also promote microcrack formation and propagation14, thereby enhancing the rock's water absorption properties.

Furthermore, as soaking time increases, the thermal expansion effect of rising temperatures reduces the rock’s permeability and porosity, thereby diminishing sandstone's water absorption properties15. In Fig. 2, when soaking for 0.5 h, the water content of red sandstone follows the pattern: ω55°C > ω95°C > ω85°C > ω25°C. Compared to the water content at 25 °C, the contents at 55 °C, 95 °C, and 85 °C are higher by 40.82%, 22.45%, and 6.12%, respectively, indicating that when the water content is low, the temperature effect on water absorption is more significant than the thermal expansion effect. After 1 h of soaking, the pattern shifts to ω55°C > ω25°C > ω85°C > ω95°C. Compared to the water content at 25 °C, the content at 55 °C increases by 6.17%, while it decreases by 3.7% and 11.73% at 85 °C and 95 °C, respectively. This shows that as the water content increases, the thermal expansion effect begins to manifest. After 3 h, the pattern is ω55°C > ω85°C > ω95°C > ω25°C. The contents at 55 °C, 85 °C, and 95 °C are higher than at 25 °C by 48.28%, 43.84%, and 32.02%, respectively. This further demonstrates that at the 3-h mark, when red sandstone is in a saturated state, the influence of temperature on water absorption decreases while the thermal expansion effect becomes more pronounced. At the 3.5-h and 4-h marks, the red sandstone reaches near saturation, with only a slight increase in water content compared to the 3-h point.

From the above analysis, it is also clear that in a saturated state (after 3, 3.5, and 4 h of soaking), the lowest water content is at 25 °C, and the highest is at 55 °C. Wang et al. using a 3D topography measurement instrument, scanned the joint surfaces of sandstone and gneiss at varying temperatures (below 100 °C) and soaking durations, finding that the joint surface parameters increased with temperature and showed an initial rise followed by a decline, peaking at 50 °C16. This aligns well with the findings of this experiment, indicating that the impact of temperature on water–rock interactions is most significant at 50 °C.

Effects of temperature and soaking time on the mechanical properties of red sandstone

From the above analysis, it can be seen that the water content of the red sandstone is different at different temperatures and different soaking times, in order to further study the effect of different water content on the mechanical properties of the red sandstone, this section focuses on the peak strength, modulus of elasticity, and expansion starting stress of the red sandstone after soaking, the results of which are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Based on the analysis of Fig. 3, it can be observed that at the same soaking time, the peak strength, elastic modulus, and dilatancy onset stress of red sandstone all show an initial decrease followed by an increase as temperature rises. The reason is that when the temperature is lower (25 ℃), the red sandstone does not produce newborn cracks, so its water content is lower, and 55 ℃ due to the temperature rise produces a certain amount of newborn cracks, and the effect of thermal expansion has not yet appeared, so the red sandstone has the highest water content, and the higher the water content produces more intergranular cracks17,18, so its mechanical parameters are smaller. As the temperature continues to rise (85 °C and 95 °C), the thermal expansion effect gradually manifests, reducing the water content of the red sandstone and causing pore closure, which reinforces the rock’s load-bearing capacity to some extent. Consequently, the mechanical parameters increase. Under consistent temperature conditions, peak strength decreases as soaking time increases, while the elastic modulus and dilatancy onset stress show a decreasing trend followed by an increase. This is because, after soaking for 1 h compared to 0.5 h, the water content of the red sandstone increases significantly, but the internal pores remain unfilled, leading to a notable reduction in mechanical parameters. After 3 h of immersion, the water content of the red sandstone has been close to saturation, at this time, the pores and microfissures within the red sandstone have been basically filled with water, only a certain water content of the rock for static compression, pore water pressure has less impact19, but in the temperature of the thermal expansion effect, part of the water is sealed in the pores and the formation of a more stable structure of the rock, can not be discharged in time in the compression, so as to provide a certain red sandstone Stiffness, so in the immersion of 3 h each mechanical parameter is improved again.

Influence of temperature and soaking time on the location of characteristic stress points

In order to research the evolution process and damage type of internal cracks in rocks under stress, MARTIN firstly proposed the concept of characteristic stress point20. There exist many methods to determine the characteristic stress point, among which the energy-based dissipation rate-transverse strain difference synthesis method21 integrates the rock energy and deformation properties, so this paper adopts the energy dissipation rate-transverse strain difference method to determine the characteristic stress point.

The total stored energy of a rock, U0, is approximately equal to the sum of the elastic energy released by the rock (Ue) and the plastic energy (Ud). Thus, the equation for calculating the total stored energy of the rock is:

where Uo is the total stored energy per unit volume of rock (MJ), Ue is the releasable elastic energy (MJ), Ud is the dissipated energy (MJ), \( \sigma _{{{\text{1i}}}} \) and \( \sigma _{{{\text{1i-1}}}} \) are the corresponding principal stresses, \( \varepsilon_{{{\text{1i}}}} \) and \( \varepsilon_{{{\text{1i-1}}}} \) are the corresponding principal strains, \( \varepsilon_{{{1}}} \) ε1 is the principal strain, and i denotes the data point index.

The formula for calculating the elastic energy Ue is as follows:

where σ1 is the principal stress and E0 is the initial elastic modulus (GPa).

Thus, the formula for calculating the dissipated energy Ud is as follows22:

Liu et al.23 used the ratio of stress to peak stress (σi/σf) on the x-axis and energy rates (elastic energy rate Ue/U0, dissipated energy rate Ud/U0) on the y-axis to plot the energy dissipation rate curve. The stress points corresponding to the maximum and minimum values of the dissipated energy rate are defined as the crack closure stress point (σcc) and the crack damage stress point (σcd), respectively. Martin et al.20 determined the crack initiation stress point (σci) using the transverse strain difference method. The specific procedure is as follows: plot the transverse strain-axial stress curve, draw a reference line from the damage stress point (σcd) to the origin, and calculate the difference between the transverse strain under the same stress and the reference line as the transverse strain difference (ΔLSR). The stress point corresponding to the maximum ΔLSR is the crack initiation stress point (σci). The schematic diagram for determining the characteristic stress points is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Following the method described above to identify characteristic stress points, the characteristic stresses for red sandstone under various temperatures and soaking times were determined. The ratio of each characteristic stress to the peak stress reflects the relative position of the characteristic stress points on the stress–strain curve. Thus, the ratios of each characteristic stress to the peak stress are presented in Table 2.

Analysis of Table 2 reveals that the ratio of crack closure stress to peak stress (σcc/σf) remains around 0.1, while the ratio of damage stress to peak stress (σcd/σf) hovers around 0.9. This suggests that the positions of the crack closure and damage stress points in red sandstone are minimally affected by temperature and soaking time, and thus are not the focus of this analysis. However, the ratio of crack initiation stress to peak stress (σci/σf) is significantly influenced by temperature and soaking time, making it a key subject of this study. The variation characteristics of the ratio of crack initiation stress to peak stress (σci/σf) with temperature and soaking time are illustrated in Fig. 5.

From Fig. 5a, it can be observed that at the same soaking time, the ratio of crack initiation stress to peak stress (σci/σf) generally exhibits an initial increase followed by a decrease as temperature rises. At lower temperatures, as the temperature increases, the water content in red sandstone rises, causing a significant reduction in peak stress, which results in an increase in the ratio. At higher temperatures, the increase in internal microcracks leads to rock deterioration, reducing the crack initiation stress. Additionally, higher temperatures cause a reduction in water content and a subsequent increase in peak stress, resulting in a lower ratio of crack initiation stress to peak stress.

From Fig. 5b, at the same temperature, the ratio of crack initiation stress to peak stress (σci/σf) first decreases and then increases with soaking time. Compared to 0.5 h of soaking, the water content at 1 h is significantly higher, leading to a noticeable increase in the deterioration of red sandstone. As a result, the crack initiation stress decreases more sharply than the peak stress, leading to a substantial drop in the ratio compared to the 0.5-h mark. At 3 h of soaking, the red sandstone reaches a saturated state, with pore water and water films forming stable links that provide some rigidity to the sandstone. The crack initiation stress thus increases more than the peak stress, causing the ratio to rise.

In summary, the ratios of crack closure stress to peak stress (σcc/σf) and damage stress to peak stress (σcd/σf) are minimally affected by temperature and water content. However, the ratio of crack initiation stress to peak stress (σci/σf) is closely related to the water content of the sandstone. At the same soaking time, the ratio of crack initiation stress to peak stress (σci/σf) increases initially and then decreases with rising temperature. At the same temperature, the ratio decreases initially and then rises with increasing soaking time.

Crack initiation stress typically represents the minimum stress required for rock to fracture or break under external force, holding significant engineering importance. Based on the above conclusions, during actual engineering construction, special attention should be given to the water content of surrounding rock at different temperatures. When the water content reaches that of approximately 1 h of soaking, the crack initiation stress will sharply decrease, making the surrounding rock more prone to instability.

Analysis of acoustic emission RA-AF parameters and failure modes based on characteristic stress segmentation points

Based on the characteristic stress points determined by the energy dissipation principle and the transverse strain difference method above, the RA-AF signal values are segmented. According to the research conclusions of related scholars24, the slope of 2 is taken as the segmentation line in this paper. The distribution of RA-AF signals of red sandstone at each temperature and immersion time with its corresponding damage pattern is illustrated in Fig. 6.

From Fig. 6, it’s evident that RA-AF signals are least abundant in the compaction stage, but the number increases as the compression test progresses, with the signals clustering closer to the origin. Most of the signals across all stages are found above the dividing line in the tensile region, indicating that tensile failure dominates in red sandstone during uniaxial compression across different temperatures and soaking times. The most significant signal changes occur during the stable and unstable crack propagation stages, with fewer signals in other stages.

At the same soaking time, the number of signals does not vary significantly with increasing temperature after 0.5 h of soaking. However, for soaking durations of 1 and 3 h, the number of signals initially decreases and then increases, reaching its lowest count at 55 °C.

When soaking time increases at the same temperature, the number of signals gradually decreases. This is because the increasing water content in red sandstone makes it difficult to capture certain signals and also leads to acoustic wave energy attenuation in pore water, resulting in fewer RA-AF signals. Additionally, with prolonged soaking, the number of signals in the tensile region noticeably decreases while those in the shear region remain relatively stable, raising the proportion of signals in the shear region below the dividing line. Despite this, most signals still occur in the tensile region above the dividing line. Thus, tensile failure is the primary failure mode during uniaxial compression of red sandstone across varying soaking times and temperatures, which aligns with the observed failure patterns in the specimens shown in Fig. 6.

Red sandstone damage evolution equation

Based on the principle of strain equivalence, the damage to red sandstone under the combined effects of temperature and water is considered the initial damage state, while load damage represents the secondary damage state. Thus, a damage constitutive equation for red sandstone under the combined effects of temperature, water, and load is established, as illustrated in Fig. 7. The previous analysis shows that the water content of red sandstone has a strong correlation with its mechanical properties, characteristic stress point positions, RA-AF parameters, and failure patterns. This section uses the water content of red sandstone soaked at room temperature (25 °C) as the baseline to represent the influence of water. For other temperatures, the increase in water content (Δω) compared to 25 °C indicates the effect of temperature on red sandstone. The relationship between temperature and the increase in water content at various soaking times is shown in Fig. 8.

From Fig. 8, it can be seen that as temperature increases, the additional water content (Δω) of red sandstone, relative to its water content at room temperature (25 °C), initially increases before decreasing across all soaking times. The trend is consistent, so this change in water content (Δω) is used to represent the influence of temperature on red sandstone. When soaked for 3 h, red sandstone reaches a saturated state, offering an accurate portrayal of temperature's effect on the rock. Therefore, this study focuses on the damage evolution and constitutive equation of red sandstone soaked for 3 h.

Initial damage variable of red sandstone under the combined effects of temperature and water

Previous studies have demonstrated that changes in the water content of red sandstone samples lead to changes in their macroscopic mechanical parameters, such as strength and elastic modulus. Hence, water content and elastic modulus are closely related, and water content can be used to quantify rock damage25,26. Since the water content of red sandstone samples soaked for 3 h at various temperatures is at its maximum and near saturation, it most accurately reflects the rock’s damage, while the original dry red sandstone is unaffected by temperature or water. Therefore, these two states are used for analyzing the relationship between the elastic modulus and water content of red sandstone, as shown in Fig. 9. The elastic modulus when using uniaxial compression only represents the initial damage variable, and even without compression, the initial damage still exists.

In Fig. 9, a strong linear relationship between water content and the elastic modulus is evident across the dry and 3-h soaked samples. The fitted equation accurately reflects the relationship between the water content and elastic modulus of red sandstone.

The elastic modulus can be used to characterize rock damage, and the damage variable of red sandstone under the combined effects of temperature and water can be expressed as:

where: D1, damage variable of red sandstone under the combined effects of temperature and water; E1, elastic modulus of red sandstone at various soaking times and temperatures (GPa); E0, elastic modulus of dry red sandstone (GPa).

Substituting the fitted curve of water content and elastic modulus from Fig. 9 into Eq. (4) yields the relationship between water content and damage D1:

For samples soaked for 3 h, the water content at each temperature can be divided into baseline water content at room temperature (25 °C) and the additional content caused by higher temperatures, representing the effects of water and temperature, respectively. This relationship is shown in Fig. 10.

Substituting the water content data from Fig. 10 into Eq. (5) yields the damage of red sandstone due to temperature and water, as illustrated in Fig. 11.

As seen in Fig. 11, the combined effects of temperature and water primarily result in damage due to water. The damage D1 of red sandstone under both factors initially increases and then decreases as temperature rises, with values consistently below 0.2.

Damage variable of red sandstone under load

Under load, microcracks continue to form inside the red sandstone. When these microcracks expand and coalesce into a primary crack, which lead to macroscopic failure of the red sandstone. Assuming that rock strength follows a Weibull distribution, previous research27 has derived the damage variable of red sandstone under load as follows:

where: D2, damage variable of red sandstone under load; m, F, F0, Weibull distribution parameters.

According to the strain equivalence hypothesis and the definition of the rock damage constitutive relationship in the Kachanov continuous damage model:

Substituting Eq. (6) into Eq. (7) gives:

The Drucker-Prager criterion is used as the failure criterion for the rock:

where φ, internal friction angle (°); I1, first invariant of the stress tensor; J2, second invariant of the deviatoric stress tensor.

In uniaxial compression:

In Eq. (12), σ denotes the effective stress in MPa.

For uniaxial compression: \(\sigma_{2}^{\prime } = \sigma_{3}^{\prime } = 0\).

Taking the derivative of both Eqs. (8 and 13) yields:

Under critical conditions, substituting into Eqs. (12) and (13) provides:

where σc and εc represent the stress and strain of the rock under critical failure conditions, respectively.

Substituting Eq. (16) into Eq. (6) yields:

where D2 is the damage variable of red sandstone under load. By substituting the values of σc and εc under each condition into Eq. (16), the m value can be determined, and then substituting this into Eq. (17) will yield the trend of damage variable D2 of red sandstone under load at different temperatures and soaking durations as a function of strain (ε). The trend is shown in Fig. 12.

Figure 12 illustrates that the growth of damage variable D2 in red sandstone under load can be divided into three stages: initial stage, rapid growth stage, and slow growth stage. In the initial stage, red sandstone is in the compaction and elastic stages, with internal pores and cracks closing and only a few new cracks forming. Therefore, the damage increases slowly, which is consistent with the observation of low RA-AF signal counts during the compaction and elastic stages in Section “Analysis of acoustic emission RA-AF Parameters and failure modes based on characteristic stress segmentation points”. In the rapid growth stage, red sandstone is in the stable and unstable crack propagation stages, where the internal elastic energy is largely converted into dissipated energy, generating many new cracks. After reaching the peak stress, red sandstone fails, and damage variable D2 increases at the fastest rate, corresponding to the RA-AF signals observed in the stable and unstable crack propagation stages. In the slow growth stage, red sandstone is in the post-peak stage. Although new cracks continue to form, their growth rate slows down, and the damage variable approaches stability near 1, signifying the complete failure of red sandstone.

Composite damage variable of red sandstone under the combined effects of temperature, water, and load

Based on Eq. (7), the constitutive relationship of red sandstone under the combined effects of water content, temperature, and load is expressed as:

where Dω is the comprehensive damage variable under the combined effects of water, temperature, and load, and D1 andD2 retain their previously stated meanings. According to28:

Substituting the damage variables D1 and D2 into Eq. (20) yields the trend of the composite damage variable Dω of red sandstone under the combined effects of water, temperature, and load, as shown in Fig. 13.

Substituting Eqs. (4), (17), and (20) into Eq. (18), the damage constitutive model is derived as:

The parameters E0, E1, m, and εc retain the same meanings as previously described.

Since the stress–strain curves obtained from the red sandstone tests show a distinct compaction phase, the derived constitutive model does not reflect well the changes during this phase. Analyzing the distribution characteristics of the Weibull function reveals that the shape of the stress–strain curve mainly depends on the exponential term. Therefore, the constitutive model in Eq. (21) is divided at the endpoint of the compaction phase(Taking the crack closure stress point σcc determined in section “Influence of temperature and soaking time on the location of characteristic stress points” as the endpoint of the compaction stage), Establish the constitutive equation29 for the segmented compression section:

In the equation: σcc and εcc represent the stress and strain at the endpoint of the compaction phase in red sandstone, respectively; m′ is the Weibull distribution parameter for the compaction phase, while m is the parameter for subsequent phases;

Validation of red sandstone damage constitutive model

To verify the accuracy of the derived damage constitutive equation, all calculated parameters are substituted into Eq. (22) to obtain the theoretical stress–strain curve. This curve is then compared to the experimental stress–strain curve to validate the model’s accuracy, as illustrated in Fig. 14.

As illustrated in Fig. 14, the theoretical stress–strain curve derived from the model aligns well with the experimentally measured curve. The experimental curves at different temperatures after 3 h of soaking exhibit a distinct compaction phase, which fits the theoretical values well. The derived constitutive model is suitable for describing the stress–strain relationship of red sandstone in a water-saturated state below 100 °C, providing valuable theoretical insight for practical engineering applications.

Conclusions

-

1.

The water content of red sandstone increases exponentially with soaking time, while soaking temperature effectively raises the rock's saturated water content. Water content initially increases and then decreases with rising temperatures. Peak strength, elastic modulus, and dilatancy onset stress all initially decrease and then increase with rising temperatures.

-

2.

Under the same soaking time, the ratio of initial fracture stress to peak stress (σci/σf) increases first and then decreases with increasing temperature, while under the same temperature, this ratio decreases first and then increases with increasing soaking time. Most of the acoustic emission signals (RA-AF) are distributed in the tensile zone, but with increasing soaking time, the proportion of signals in the shear zone gradually increases, although still much fewer than those in the tensile zone, consistent with the predominant tensile failure mode observed in the red sandstone specimens during testing.

-

3.

The water content of red sandstone soaked at room temperature (25 °C) is used as the baseline to represent the influence of water. The increase in water content (Δω) compared to room temperature represents the influence of temperature on red sandstone. The damage constitutive equation of red sandstone under the combined effects of temperature, water, and stress fits well with the experimental stress–strain curves and is suitable for analyzing damage in red sandstone below 100 °C in a water-saturated state.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Liang, X. F. et al. Evolution of permeability and pore structure of salt rock and its self-healing mechanism under coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical environment. J. Energy Storage 66, 107476 (2023).

Meng, T. et al. Temperature-dependent evolution of permeability and pore structure of marble under a high-temperature thermo-hydro-mechanical coupling environment. Acta Geotech. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-023-02163-1 (2024).

Zhang, Y. Study on the seepage regularity and water inrush mechanism of fracture rock mass under coupling action of stress field and hydraulic force. In University of Science and Technology Beijing (2020).

Bian, K. et al. Mechanical behavior and damage constitutive model of rock subjected to water-weakening effect and uniaxial loading. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52, 97–106 (2019).

Long, L. Study on mechanical and seepage properties of sandstone under the coupling of temperature-seepage-stress. In Chongqing University (2021).

Guo, Q. F. et al. Mechanical properties and damage evolution of granite under high temperature thermal shock. Chin. J. Eng. 44, 1746–1754 (2022).

Liu, X. X. et al. Influence of water temperature on mechanical properties of argillaceous siltstone by experimental study. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 10, 586–592 (2014).

Gao, Y. N. et al. Finite deformation analysis on sandstone subjected to thermo-hydro-mechanical (T-H-M) coupling. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 48, 159–177 (2015).

Lu, Y. L. et al. Experimental study of the influence of water and temperature on the mechanical behavior of mudstone and sandstone. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 76, 645–660 (2017).

Xu, Y. et al. Experimental study on the permeability evolution of argillaceous sandstone under elevated temperatures. Eng. Geol. 2023, 313 (2023).

Wong, L. N. Y., Maruvanchery, V. & Liu, G. Water effects on rock strength and stiffness degradation. Acta Geotech. 11, 713–737 (2016).

Yu, C. Y. et al. The effect of water on the creep behavior of red sandstone. Eng. Geol. 253, 64–74 (2019).

Hu, Z. et al. Study on ground temperature characteristics and prediction of high ground temperature tunnel. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 17, 1906–1915 (2021).

Zhao, Z. H. Thermal influence on mechanical properties of granite: A microcracking perspective. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49, 747–762 (2016).

Benzagouta, M. S. & Amro, M. M. Pressure and temperature effect on petrophysical characteristics: carbonate reservoir case. In Presented at SPE Saudi Arabia Section Technical Symposium, Society of Petroleum Engineers (Year Unknown) (2023).

Wang, F. et al. The influence of temperature and time on water-rock interactions based on the morphology of rock joint surfaces. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 3385–3394 (2019).

Li, H. R. et al. Effect of water saturation on dynamic behavior of sandstone after wetting-drying cycles. Eng. Geol. 319, 107105 (2023).

Li, H. R. et al. Effect of water on mechanical behavior and acoustic emission response of sandstone during loading process: Phenomenon and mechanism. Eng. Geol. 294, 106386 (2021).

Cheng, T. et al. Strength and acoustic emission weakening mechanism of sandstone after prolonged water immersion: Insights from micro-fracture. Eng. Fract. Mech. 291, 109571 (2023).

Martin, C. D. & Chandler, N. A. The progressive fracture of Lac du Bonnet granite. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 31, 643–659 (1994).

Wang, H. Mechanical properties and fatigue constitutive model of argillaceous quartz siltstone under cyclic loading. In University of Science and Technology Beijing (2023).

Song, H. Q. et al. Revised energy drop coefficient based on energy characteristics in the whole process of rock failure. Rock Soil Mech. 40, 91–98 (2019).

Liu, X. H. et al. Study on determination of uniaxial characteristic stress of coal rock under quasi-static strain rate. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 39, 2038–2046 (2020).

Niu, Y., Zhou, X. P. & Berto, F. Evaluation of fracture mode classification in flawed red sandstone under uniaxial compression. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 107, 102528 (2020).

Chai, Y. G. et al. Research on blasting damage evolution model of water bearing red sandstone under high strain rate. Eng. Blast. 28, 23–32 (2022).

Li, B. B. et al. Mechanical properties and damage constitutive model of coal under the coupled hydro-mechanical effect. Rock Soil Mech. 42, 315–323 (2021).

Jiang, H. P. et al. Statistical damage constitutive model of high temperature rock based on Weibull distribution and its verification. Rock Soil Mech. 42, 1894–1902 (2021).

Jia, P. et al. Energy evolution and piecewise constitutive model of freeze-thaw damaged sandstone. J. Cent. South Univ. Sci. Technol. 54, 908–919 (2023).

Song, Y. J. & Cao, J. H. Research on damage mechanical properties of sandstone under the combined action of freeze-thaw and load. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 1–12 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors of the article sincerely appreciate and thank all the people who made it possible to implement this project.

Funding

This research is supported by the Basic Scientific Research Business Fee Project of Universities Directly under the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Grant No. 2024XKJX009); Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia of China (Grant Nos. 2024LHMS05044 and 2020LH05018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiankai Bao and Jianlong Qiao designed the study and supervised the project. Chaoyun Yu, Baolong Tian and Lingyu Wang collected data. Xiaofan Zhang performed the statistical analysis. Xiankai Bao and Jianlong Qiao wrote the initial paper. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, X., Qiao, J., Yu, C. et al. Experimental research on damage characteristics of red sandstone under the combined action of temperature, water and stress. Sci Rep 14, 17012 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67833-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67833-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Experimental study on the influence of ground temperature and pore water pressure on the mechanics of excavation unloading sandstone

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Investigation on surface condition surveys and study on weathering mechanism of the stone wall at the Zhouqiao bridge ruins in Kaifeng

npj Heritage Science (2025)