Abstract

This study investigated the effects of corn cob biochar (CCB) and rice husk biochar (RHB) additions (at 0%, 5%, and 10% w/w) on nitrogen and carbon dynamics during co-composting with poultry litter, rice straw, and domestic bio-waste. The study further assessed the temperature, moisture, pH, and nutrient contents of the mature biochar co-composts, and their potential phytotoxicity effects on amaranth, cucumber, cowpea, and tomato. Biochar additions decreased NH4+-N and NO3- contents, but bacteria and fungi populations increased during the composting process. The mature biochar co-composts showed higher pH (9.0–9.7), and increased total carbon (24.7–37.6%), nitrogen (1.8–2.4%), phosphorus (6.5–8.1 g kg−1), potassium (26.8–42.5 g kg−1), calcium (25.1–49.5 g kg−1), and magnesium (4.8–7.2 g kg−1) contents compared to the compost without biochar. Germination indices (GI) recorded in all the plants tested with the different composts were greater than 60%. Regardless of the biochar additions, all composts treatments showed no or very minimal phytotoxic effects on cucumber, amaranth and cowpea seeds. We conclude that rice husk and corn cob biochar co-composts are nutrient-rich and safe soil amendment for crop production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Waste management is a significant challenge in many sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. Sustainable waste management in SSA is constrained by inadequate infrastructure, limited financial resources, and a lack of awareness.1,2,3 SSA countries adopt different waste management approaches based on their socio-economic development, population density, and national policies.4 In Ghana, waste management is problematic due to rapid urbanization and improvements in standards of living, particularly in the urban areas, which has resulted in large amounts of domestic and market wastes.5,6,7 Odonkor and Sallar7 reported that in Ghana, waste materials are often dumped in open areas, wetlands, landfills, and uncontrolled dumpsites or incinerated in the open air. Studies have shown that the poor wate management systems have health-related consequences including intestinal worm infestation, acute eye infections, cholera and typhoid fever.8,9

Research findings indicated that domestic solid waste and industrial waste, which are the dominant types of waste in Ghana contain over 60% of organic and decomposable waste.10,11 Miezah et al.12 estimated that the average waste generated in Ghana is 0.47 kg per person per day, equivalent to approximately 12,710 tons of waste per day. Miezah et al.12 estimated that two Ghanaian cities, Accra and Kumasi, alone generate approximately 4,000 tons of waste daily. Adanu et al.5 opined the revenue and energy potentials of these wastes can be tapped through their use as a resource by industries to improvethe quality of life of many Ghanaians. Composting has been considered as a sustianble way to manage organic waste materials 13 in that compost offers the potential to divert organic waste from landfills. Compost produced from organic waste materials can be used as a soil amendment to improve soil structure, enhance moisture retention, and supply nutrients for improved crop production.1,13,14 However, improper organic waste composting can lead to nutrients loss through volatilization, leaching, and greenhouse gas emissions1,15,16 with negative environmental implications.

Significant N losses occur during composting of organic materials, especially nutrient-rich feedstock such as animal manure.17,18,19 N losses during composting represent a major problem as it significantly influences the agronomic value of the final compost product.20 N losses during composting are reported to occur through N2O and NH3 emissions, which produce unpleasant odour with potential environmental health implications.1,15 Sanchez-Monedero et al.20 reported that reduced N losses due to biochar addition range from 6–86.4% with biochar application rates of 3–25%. They further explained that during composting, the reactivity of biochar increases due to surface ageing, which involves the development of acid and basic functional groups through the oxidation of the biochar matrix and the formation of organic coating.

Co-composting, the process of composting organic waste with biochar, can be explored as an innovative and sustainable waste management solution to mitigate the adverse environmental impacts of improper organic waste management approaches. Addition of biochar to organic waste during composting can minimise carbon and nitrogen substrate availability for greenhouse gas (GHG) production. GHG emissions from biochar or biochar co-compost amended soils is likely to be low due to biochar’s high internal surface area and sorption capacity, which promotes complex interactions between biochar and soil components.21 These reactions increased soil pH,22,23 reduced soil bulk density,24,25 reduced losses of nutrients26,27 and greenhouse gas emissions from the amended soils.17,28,29 Similar interactions are also reported to occur during composting when biochar is used as part of the composting material.30

The addition of biochar during composting accelerates the composting process by increasing the temperature of the compost mixture and providing a large surface area for microbes that mediate the decomposition process31,32. Biochar’s micropores and macropores, which are comparable in size to bacteria, provide shelter for microorganisms, allowing them to proliferate with limited stresses from inhibitory compounds, competitors, and environmental factors such as pH, leaching, and desiccation.20 Biochar addition during composting has been reported to minimize C and N losses33,34 and decrease N2O and CH4 emissions35,36,37 compared to composting without biochar.

According to Zucconi,38 phytotoxicity effects of compost are attributable to a combination of factors including the presence of heavy metals, ammonia, soluble salts and low molecular weight organic acids. To guarantee the safe use of composts, simple methods are often used to assess their toxicity to growing plants.39 These methods include seed germination and plant growth tests using compost extract.38,39,40 The phytotoxicity test result is indicative of whether co-composting biochar with organic materials yields well-matured compost free of phytotoxins that inhibit seed germination and seedling development or not. This biological testing method is used to screen organic waste composts for their suitability for soil application.41 Many studies have investigated compost phytotoxicity using different plant species such as cucumber, radish and tomato,39 Maize,42 chickpea and soybean43 and garden cress.44

The specific objectives of this study were to (i) investigate the effects of corn cob biochar and rice husk biochar additions on nutrient (N and C) dynamics during composting with organic waste materials such as poultry litter, rice straw and domestic bio-waste, (ii) assess the effect of biochar addition on bacterial and fungal populations during composting of organic waste materials, (iii) examine the phytotoxicity effects of biochar and compost on germination parameters of amaranth, cowpea, tomato and cucumber. We hypothesized that biochar co-composting with organic waste materials does not increase carbon stabilization or reduce nitrogen mineralization, does not increase bacterial and fungal populations, and does not impose phytotoxicity effects on seed germination and seedling development of amaranth, cucumber, tomato, and cowpea.

The novelty of this study is that biochar addition at the time of composting is a sustainable way of recycling organic waste for biochar co-compost production. Biochar co-compost can be added to soil to improve soil quality, increased crop yields and enhance livelihoods of farmers and their households. Additionally, this study contributes knowledge on sustainable organic waste management practices in SSA, showcasing the potential of biochar co-composting to enhance compost quality and improve soil health.

Materials and methods

Study area and experimental setup.

The composting was done at the A. G. Carson Technology Center of the University of Cape Coast (5° 07′ 45.64′′ N; 1° 17′ 09.94′′ W), Ghana. The basic feedstocks used for composting were poultry litter (PL), rice straw (RS), domestic bio-waste (DBW), and biochars–rice husk biochar (RHB) and corn cob biochar (CCB). The DBW, PL and RS were composted with either RHB or CCB in 1 m3 wooden bins. The experimental set-up comprised a factorial design involving five treatments with four replications each. The amounts of DBW, PL, and RS in each compost treatment mixture were 100 kg, 35 kg, and 30 kg, respectively (dry weight basis), with 0%, 5% or 10% of either RHB or CCB added. Thus, the treatments were 0%B (DBW, PL and RS mixtures without biochar), 5%RHB (DBW, PL and RS mixtures containing 5% rice husk biochar), 10%RHB (DBW, PL and RS mixtures containing 10% rice husk biochar), 5%CCB (DBW, PL and RS mixtures containing 5% corn cob biochar) and 10%CCB (DBW, PL and RS mixtures containing 10% corn cob biochar). To ensure homogeneity, each treatment components were mixed thoroughly in a concrete mixer machine for 15 min before being poured into the 1 m3 compost bin. The composting lasted for 60 days, with periodic manual mixing in every 3 days in the first 2 weeks and weekly in the subsequent weeks. Water was added periodically to maintain moisture content of the compost mixes at approximately 60% throughout the composting process to ensure adequate moisture availability while enabling oxygen supply for optimal microbial activities.45

Samples of the compost was collected at specific time points to determine changes in temperature, moisture, pH, and electrical conductivity (EC) during the composting process. The mesophilic, thermophilic, and maturation phases of the composting was detected based on temperature values. Four replicates per treatment were sampled on each specific date to ensure statistical robustness and representativeness of the sample.46,47

Feedstock collection and characterization

The PL was collected from the University of Cape Coast Teaching and Research Farm, Ghana, and comprised a mixture of droppings, beddings, and feeds of chickens under the deep litter subsystem of broiler and layer production. The RS was collected from rice farmers’ fields at Wamaso and Kobina Anno towns in the Central Region of Ghana and manually chopped into pieces (< 10 cm). The DBW was collected from local markets and food vendors within the Cape Coast metropolis of the Central Region of Ghana. The DBW was primarily composed of vegetable waste, fruit peels (mostly pineapple, watermelon, and pawpaw), and peels from yam, cassava, and plantains. To ensure that the feedstock was uniformly mixed prior to composting, all components were shredded into smaller pieces and thoroughly mixed using a clean concrete mixer.

Corn cob biochar (CCB) and rice husk biochar (RHB) were purchased from Lucky Star Pure Charcoal Limited, Kumasi, Ghana. The corn cobs were pyrolyzed at 400° C, while the rice husks were pyrolyzed at 550° C. The chemical properties of the feedstocks are presented in Table 1.

Chemical properties, microbial analysis and phytotoxicity assessment

pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured in a 1:5(w/v) compost-deionized water ratio using a combined pH and EC meter (HANNA instruments). The total carbon (TC) and total nitrogen (TN) contents were measured using the loss of ignition method48 and the Kjeldahl method49, respectively. The C/N ratio was calculated from the measured TN and TC. The total Phosphorus (P) content was extracted using the Calcium-Acetate-Lactate extraction (P CAL) method and measured on a spectrophotometer at 720 nm. Total element (K, Ca, Mg, Na, Al, Fe) concentrations were determined by nitric acid (HNO3) digestion at 120 °C using the MARS 6 Microwave Digestion System (from CEM corporation) and measured using the Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectroscopy (Ciros CCD, SPECTRO Analytical Instruments GmbH, Kleve, Germany)50. Ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) and nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) were extracted using the KCl extraction method. NH4+-N and NO3−-N were measured with a spectrophotometer (UV-1600PC) at 636 nm and 410 nm respectively.

Culturable bacteria and fungi population counts were performed using the pour plate count method.51 This method was chosen because it provides a direct measure of the viable microbial populations present in the compost samples. Although molecular techniques such as qPCR and next-generation sequencing (NGS) are increasingly used, the pour plate method remains a valuable first step approach for assessing the overall microbial activity and health of compost, especially in resource-limited situations. Nutrient agar (NA) was used to culture bacteria, and Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) was used to culture fungi. Germination tests were performed to assess the phytotoxicity effects of the matured compost on the germination parameters of cucumber, cowpea, amaranths and tomatoes. The relative seed germination (RSG), relative root elongation (RRE) and germination index (GI) were calculated as described by Peña et al.39

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.0.5. The Shapiro–Wilk Test for normality was conducted to check the normal distribution of the data. The General Linear Model (lm function in R) was used to test for differences in treatment effects on the measured variables. Data comparison was made using the multivariate Analysis of Variance under the General Linear Model with multiple range Post Hoc tests using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test to deduce treatment differences at P < 0.05. Correlation analyses were performed to compare the strengths of relationships among some of the measured parameters. Principal component analysis (PCA) was done to assess the contribution of each independent variable to the measured parameters. Germination parameters were calculated using an Excel sheet developed by Dr. Farhan Khalid, Department of Agronomy, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan. Figures were prepared and presented using OriginPro 2021b (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, USA) software.

Results and discussion

Dynamics of temperature, moisture, pH and EC during biochar co-composting

The initial temperature (6 h after the start of composting) of the compost mixtures ranged from 33 to 35 °C (Fig. 1a). All compost treatment mixtures entered the thermophilic phase (> 40 °C) one day after the beginning of the composting, lasting for nearly 20 days. Within the thermophilic phase, temperatures fluctuated between 55 and 68 °C, with the highest temperature of 68 °C being recorded in the 10%RHB treatment (Fig. 1a).

Biochar co-composts (RHBs and CCBs) showed higher temperatures and more prolonged thermophilic phases than composts without biochar (0%B). Biochar possibly stimulated microbial activity, which resulted in a greater primary fermentation intensity in biochar co-composts in agreement with Tibu et al.52 and Yu et al.53 Although biochar produced at higher temperatures (400 °C and 550 °C) typically contains more recalcitrant carbon, at the initial stages following its addition, labile carbon released from biochar decomposition into the compost mixture provide carbon and energy sources and potentially prime carbon release from other feedstocks.1 Jagadabhi et al.43 and Lim et al.14 reported that the optimal temperature range for optimum decomposition of lignocellulosic biomass is around 50–60 °C. The high temperatures observed in biochar co-composts are attributable to rapid decomposition of organic compounds and increased microbial activities.54 The high temperatures possibly contributed to disinfecting the compost materials, particularly the DBW and PL, which have been reported to contain high amounts of pathogens and contaminants.44,52,55

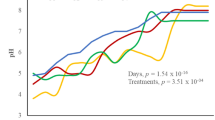

The pH of all the composts progressively increased from day 0 to day 35, and subsequently and gradually declined with time until day 60 (Fig. 1b). Biochar co-composts showed higher pH values than composts without biochar, with the CCB co-composts having higher pH than RHB co-composts. Biochar addition during composting potentially created a conducive environment that stimulated microbial activities and the subsequent release of alkali and alkali earth metals bound in the organic matter. The presence of base cations such as Ca, K, and Mg, as well as the direct release of carbonates, hydroxides, or oxides formed during biochar production, would have reacted with H+ and monomeric Al species in the compost mixtures, thereby increasing their pH.56 The initial pH values of all feedstocks used for compost preparation were greater than 7, except for DBW (pH 5.9). RHB and CCB had pH values of 10.1 and 9.8, respectively (Table 1), which is indicative that the observed pH increase in biochar co-compost treatments can be directly attributed to the high pH of the biochars.57

The initial moisture content (%MC) of the compost mixture ranged from 58 to 63% (Fig. 1c). On day 5 of composting, the 10%CCB treatment recorded the highest %MC, while on day 60, the RHB co-composts recorded the highest %MC, followed by CCB co-composts, with 0%B recording the lowest %MC. Adequate moisture content is crucial during composting as moisture influences the physiological characteristics of microorganisms and the physical structure of compost matrices.31 Thus, a well-maintained moisture content encourages active oxygen consumption and increased activity of aerobic microorganisms.58

Electrical conductivity (EC) in the 0%B treatment was significantly higher than in biochar co-composts. The 0%B treatment showed a progressive increase in EC from 9.1 mS cm−1 (day 0) to 11.4 mS cm−1 (day 40), decreasing to 10.7 mS cm−1 at day 60 (Fig. 1d). During composting, weight loss occurs due to the mineralization of organic matter which is associated with moisture use and CO2 emission, and a concentrated and drier compost. The drying process promotes the accumulation of mineral salts raising the EC of the compost mixture.43 High EC (> 4 dS m−1) has been reported to inhibit seed germination and seedling development.59,60

Changes in total C, NH 4 + -N and NO 3 − -N contents during biochar co-composting

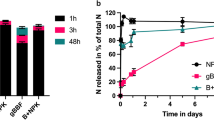

Figure 2 shows changes in ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N), nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) and total carbon content (TC) during organic waste composting with biochar. TC in all compost treatments decreased over time (Fig. 2c) as the pool size of easily decomposable C decreased.15 The decline in TC suggests the mineralization of organic matter and loss of carbon through the release of CO2 due to fermentation during the composting process.53,59,61 The relatively lower TC of the 0%B treatment reflects higher C mineralization when composting without biochar.53 Biochar addition during composting can reduce C loss by increasing the C/N ratio, which is likely to lower C mineralization. Biochar is known to contribute more recalcitrant carbon in compost-biochar mixes, which helps stabilize the organic matter and reduce carbon loss.53

The concentrations of NH4+-N and NO3−-N in all treatments were higher in the earlier stages of composting but decreased over time (Fig. 2a and 2b). The decline in NH4+-N content with time during composting could suggest N losses through ammonia volatilization, microbial or capture on biochar surface, microbial NH4+ immobilization, nitrification or their combination.62 The NH4+-N in the biochar co-compost treatments were significantly higher than the compost without biochar (0%B). In the 0%B treatment, decreased NH4+-N content reflected in an increased NO3−-N content (Figs. 2a and 2b), indicating a relatively greater nitrification rate when composting without biochar.62 Biochar addition promoted NH4+-N fixation during the thermophilic phase (around day 21) of the composting process. This was evidenced by the low NO3− -N contents even as the NH4+-N decreased with time during the composting period. This suggests that biochar helped to stabilize ammonium, reducing its conversion to nitrate and thereby minimizing nitrogen losses during the composting process.

Reduced nitrification following biochar additions could be due to the high temperatures, especially at the thermophilic stage, which inhibited the growth and activities of nitrifying bacteria.63 Biochar’s large surface area and high sorption capacity could stimulate microbial and surface NH4+ absorption leading to a net N immobilization.62 In contrast to our findings, Zhang and Sun62 found that spent mushroom waste co-composted with biochar (35% SMC and 20% biochar) had lower NH4+−N content but a higher NO3−−N content. They explained that the combined addition of spent mushroom waste and biochar created a favourable environment for nitrifying bacteria to convert NH4+ to NO3− leading to high NO3−-N content in the biochar co-compost.

Bacteria and fungi populations during co-composting

Culturable bacteria and fungi populations during composting of organic materials with biochar are illustrated in Fig. 3. By day 18 of composting, the bacteria count (Fig. 3a) and fungi count (Fig. 3b) were similar in all the composts. Significant variations in bacteria and fungi count occurred in all the composts from day 25 to day 60. These variations are attributable to fluctuations in the temperature of the compost mixtures, which significantly influenced the types and activities of microorganisms.61 Both bacteria and fungi populations in the biochar co-compost treatments were significantly (P < 0.05) higher compared to the 0%B treatment. Among the biochar co-compost treatments, bacteria and fungi count increased with increased biochar addition.

Microorganisms play a key role during composting of organic materials. They are responsible for the decomposition of organic matter, nutrient cycling, immobilization, and production and release of GHGs.64 However, during composting, their abundance and activities are affected by substrate availability and conditions such as temperature, aeration and moisture.65 Also, the regular turning and watering of the compost mixture can alter the temperature and moisture levels within the compost matrix, creating favourable conditions and supplying enough oxygen for the microorganisms.

The result of this study agrees with the findings of Malinowski et al.61 who reported a significant increase in the abundance of bacteria with increasing biochar addition. They attributed their result to the biochar’s effects on the compost pH, which they found to correlate positively with the abundance of microorganisms. Similar findings have been reported by Awasthi et al.46 and Du et al.66 Both studies reported an increase in bacteria and fungi count and activities following the addition of biochar during composting of organic waste. They concluded that biochar’s large surface area and pore size provided a suitable habitat for bacteria to colonize and proliferate, protecting them from predation and desiccation.

Biochar’s porous nature and high internal surface area make it preferable for microorganisms to colonize.47 However, the kind of microorganisms colonizing the surfaces of biochar depends on the physical and chemical characteristics of the biochar. Biochar produced at high temperatures has a higher porosity than does produced at low temperatures.67,68 The size of the pores determines which kind of microbes will have access to the internal surface area and are protected from grazing.69 High porosity biochar has high nutrient and water retention capacity, providing substrates for colonizing microbes. Although biochar contains a high amount of recalcitrant C, biochar addition during composting can also release the labile C fraction into the compost mixture as a substrate for microbial synthesis,46 especially at the initial stages of the decomposition process.

Effects of biochar addition on the matured compost quality

Table 2 shows the effects of biochar addition on the matured compost’s chemical properties. The result shows that biochar addition increased pH by 0.1 to 0.6 units. The increase in pH follows the order 10%CCB > 5%CCB > 10%RHB > 5%RHB > 0%B. Due to the high pH of the RHB (10.1) and CCB (9.8) used in the study, pH increases found in the biochar co-composts were not unexpected. It is also possible that the continuous mineralization of organic matter produced organic acids and phenolic compounds, which could have increased the buffering effects of the compost mixture.70

Carbon contents of the biochar co-compost treatments were higher than the 0%B treatment. This observation can be attributed directly to the high C content of the RHB and CCB (41% and 71% respectively). The C/N ratio can be used to determine the maturity of compost. Compost is considered matured if the C/N ratio is < 1571 or < 21.31 The lowest C/N ratio was recorded in the 0%B treatment (10.53) and the highest in the 10%CCB treatment (18.93), indicating that all compost treatments have matured. In some cases, due to the high C content of biochar, C/N ratios of > 20 in biochar co-compost treatments can be observed.72 A similar result was reported by Jindo73 when co-composting apple pomace, rice straw and rice bran biochar with poultry and cattle manure. They found that the C/N ratio in the biochar co-compost was increased by 44.4–70.1% compared to composting without biochar. Zhang and Sun62 attributed this observation to the high recalcitrant C content of the biochar, which resisted degradation throughout the composting period.

The 0%B treatment recorded significant (P < 0.05) higher values for EC, N, K, Mg, and Na compared to the biochar co-composts. This is likely due to the higher nutrient contents of the DBW, PL and RS used in the composting process (Table 1). Given that each treatment received the same quantities of DBW, PL, and RS, it is possible that the biochar, which had low nutrient content, diluted the overall nutrient concentration in the biochar co-compost treatments.

Assessing phytotoxicity effects of biochar and co-compost using seed germination bioassays

The effects of the compost extracts on relative seed germination (RSG), relative root elongation (RRE), and germination index (GI) on cucumber, amaranth, tomato and cowpea are summarised in Table 3.

Phytotoxicity effects of compost on germination parameters varied with the crop type. The result showed that RSG in cucumber and cowpea were similar for all the treatments, but these were higher (> 90%) than those found in the tomato and amaranth (< 90%). Siles-Castellano et al.44 and Bustamante et al.74 identified GI as the most important variable for assessing compost quality as it correlated negatively with EC and heavy metals. GI values of < 50% indicate high phytotoxicity, between 50–80% indicate moderate phytotoxicity, and > 80% show no phytotoxic effects.44 In this study, the GI of tomatoes recorded values below 50% in all treatments, indicating that the composts produced are highly phytotoxic to tomatoes as a result of NH3 and low molecular weight organic acid released from the compost.41 In this study, biochar addition reduced EC by 25.8% to 39.4% in RHB co-composts and 29.3% to 31.7% in CCB co-composts compared to the 0%B treatment. This observation explains why the germination parameters of the biochar co-compost treatments were greater than the 0%B treatments (Table 3).

Principal component analysis

The principal component analysis (PCA) was used to determine the relationships between the matured compost chemical properties and expression of the germination parameters to define a small set of variables to separate the groups based on their quality. PCA works by preserving the conforming Euclidean distances using a data variances and covariances matrix. When any variable’s scale or unit of measurement is extremely large, the unreal differences can be derived from the distances. The PCA correlation reveals a low correlation between variables and the two PCA components (Table 4). The variability appears to represent the relationships between the compost treatments and the measured compost chemical properties and germination variables with reliability. The components are orthogonal, meaning they are not correlated and can be analyzed independently. According to the resulting biplot generated by the correlation matrix, the two components (PC1, and PC2) accounted for 63.2% of variability, PC1 is the most important, accounting for 43.0% of total variability, with PC2 accounting for 20.2% (Fig. 4).

The biplot shows that treatments and variables are far away from each other except for P and RSG of cowpea which are in the same space with 0%B treatment (Fig. 4). When the treatments were projected perpendicularly on PC1, three distinct scenarios were displayed: 5%RHB, 10%RHB, 5%CCB, and 10%CCB were found on the PC1 component’s positive side. Simultaneously, 5%CCB and 10%CCB are on the positive side of the PC2 component. 0%B on the other hand, is in the negative quadrant of both components. When the analysis was applied, and variables with either positive or negative correlations were selected, the results showed that variables such as C, C/N, Fe, Ca, Al and all germination parameters were concentrated on the positive side of PC1 (43.0%). Variables such as pH, N, EC, K, Mg, Na, Mn and P are concentrated on the negative side. In PC2 (20.2%), pH, N, EC, K, Mg, Mn, P, C, C/N, Fe and Ca were concentrated on the positive side, whereas Na, Mn, Al, GI and RRE of cucumber, amaranth, cowpea and tomato were concentrated on the negative side. All variables were within the − 30 to 30 range of the PC1 scale whereas the treatments were within the − 5 to 5 range (Fig. 4).

In a study involving composting of sewage sludge, fruit processing waste, and manufacturing waste of fried food, Peña et al.39 reported high variability in the PCA. The PC1 and PC2 contributed 72.4% of the total variability, with PC1 contributing 39.1% and PC2 contributing 32.4%. They also observed high positive and negative correlation (above 0.70 up to 0.95) in both components, with the germination parameters concentrated on the positive side of PC1. In this study, the germination parameters were on the positive side of PC1, and on the negative side of PC2. This observation suggests that biochar co-compost had a greater influence on the germination parameters compared to compost without biochar.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the potential of co-composting organic waste with biochar as a sustainable approach to organic waste management. The addition of corn cob and rice husk biochar improved the efficiency of the composting process, influencing temperature, pH, microbial activities and nutrient dynamics. The study confirmed the hypothesis that although biochar co-composting with organic waste materials increased bacterial and fungal populations, it stabilized carbon, while decreasing net nitrogen mineralization. The study also showed that addition of biochar during co-composting did not impose phytotoxicity effects on seed germination and seedling development.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ayilara, M. S., Olanrewaju, O. S., Babalola, O. O. & Odeyemi, O. Waste management through composting: Challenges and potentials. Sustainability (Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114456 (2020).

Bratina, B. et al. From municipal/industrial wastewater sludge and FOG to fertilizer: A proposal for economic sustainable sludge management. J. Environ. Manage. 183, 1009–1025 (2016).

Buor, D. Perspectives on solid waste management practices in urban Ghana: A review. J. Waste Manag. 2(2), 1–9 (2020).

Cerda, A. et al. Composting of food wastes: Status and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 248, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.133 (2018).

Adanu, S. K., Gbedemah, S. F. & Attah, M. K. Challenges of adopting sustainable technologies in e-waste management at Agbogbloshie. Ghana. Heliyon 6, e04548 (2020).

Boateng, K. S. et al. Household willingness-to-pay for improved solid waste management services in four major metropolitan cities in Ghana. J. Environ. Pub. Health 2019(1), 5468381 (2019).

Odonkor, S. T. & Sallar, A. M. Correlates of household waste management in Ghana: implications for public health. Heliyon 7, e08227 (2021).

Addo, I. B., Adei, D. & Acheampong, E. O. Solid waste management and its health implications on the dwellers of Kumasi metropolis, Ghana. Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci. 7, 81–93 (2015).

Odonkor, S. T. & Mahami, T. Healthcare waste management in Ghanaian hospitals: Associated public health and environmental challenges. Waste Manage. Res. 38, 831–839 (2020).

Adu-Boahen, K. et al. Waste management practices in Ghana: Challenges and prospect, Jukwa Central Region. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 3(3), 530–546 (2014).

Owusu-Ansah, P., Obiri-Yeboah, A. A., Nyantakyi, E. K., Woangbah, S. K. & Yeboah, S. I. I. K. Ghanaian inclination towards household waste segregation for sustainable waste management. Sci. African 17, e01335 (2022).

Miezah, K., Obiri-Danso, K., Kádár, Z., Fei-Baffoe, B. & Mensah, M. Y. Municipal solid waste characterization and quantification as a measure towards effective waste management in Ghana. Waste Manage. 46, 15–27 (2015).

Pergola, M. et al. Composting: The way for a sustainable agriculture. Appl. Soil Ecol. 123, 744–750 (2018).

Lim, L. Y. et al. Review on the current composting practices and the potential of improvement using two-stage composting. Chem. Eng. Trans. 61, 1051–1056 (2017).

Cáceres, R., Malińska, K. & Marfà, O. Nitrification within composting: A review. Waste Manage. 72, 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.10.049 (2018).

Sanchez-Monedero, M. A., Roig, A., Paredes, C. & Bernal, M. P. Nitrogen transformation during organic waste composting by the Rutgers system and its effects on pH, EC and maturity of the composting mixtures. Bioresour. Technol. 78, 301–308 (2001).

Agyarko-Mintah, E. et al. Biochar lowers ammonia emission and improves nitrogen retention in poultry litter composting. Waste Manage. 61, 129–137 (2017).

Chen, Y., Zhang, X., Chen, W., Yang, H. & Chen, H. The structure evolution of biochar from biomass pyrolysis and its correlation with gas pollutant adsorption performance. Bioresour. Technol. 246, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.08.138 (2017).

López-Cano, I., Roig, A., Cayuela, M. L., Alburquerque, J. A. & Sánchez-Monedero, M. A. Biochar improves N cycling during composting of olive mill wastes and sheep manure. Waste Manage. 49, 553–559 (2016).

Sanchez-Monedero, M. A. et al. Role of biochar as an additive in organic waste composting. Bioresour. Technol. 247, 1155–1164 (2018).

Thies, J. E., Rillig, M. C. & Graber, E. R. Biochar effects on the abundance, activity and diversity of the soil biota. in Biochar for Environmental Management: Science, Technology and Implementation 327–389 (Routledge, 2015).

Chintala, R., Mollinedo, J., Schumacher, T. E., Malo, D. D. & Julson, J. L. Effect of biochar on chemical properties of acidic soil. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 60, 393–404 (2014).

Frimpong, K. A., Abban-Baidoo, E. & Marschner, B. Can combined compost and biochar application improve the quality of a highly weathered coastal savanna soil?. Heliyon 7(5), e07089 (2021).

Amoakwah, E., Frimpong, K. A., Okae-Anti, D. & Arthur, E. Soil water retention, air flow and pore structure characteristics after corn cob biochar application to a tropical sandy loam. Geoderma 307, 189–197 (2017).

Jien, S. H. Physical characteristics of biochars and their effects on soil physical properties. in Biochar from Biomass and Waste: Fundamentals and Applications 21–35 (Elsevier, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811729-3.00002-9.

Gupta, R. K. et al. Rice straw biochar improves soil fertility, growth, and yield of rice-wheat system on a sandy loam soil. Exp. Agric. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479719000218 (2019).

Rawat, J., Saxena, J. & Sanwal, P. Biochar: A Sustainable Approach for Improving Plant Growth and Soil Properties. in Biochar - An Imperative Amendment for Soil and the Environment (IntechOpen, 2019). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.82151.

Agegnehu, G. et al. Biochar and biochar-compost as soil amendments: Effects on peanut yield, soil properties and greenhouse gas emissions in tropical North Queensland. Australia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 213, 72–85 (2015).

Lai, W. Y. et al. The effects of woodchip biochar application on crop yield, carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions from soils planted with rice or leaf beet. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 44, 1039–1044 (2013).

Das, S. K. et al. Innovative biochar and organic manure co-composting technology for yield maximization in maize-black gram cropping system. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-021-01519-5 (2021).

Khan, N. et al. Maturity indices in co-composting of chicken manure and sawdust with biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 168, 245–251 (2014).

Chaher, N. E. H. et al. Optimization of food waste and biochar in-vessel co-composting. Sustainability (Switzerland) 12, (2020).

Czekała, W. et al. Co-composting of poultry manure mixtures amended with biochar - The effect of biochar on temperature and C-CO2 emission. Bioresour. Technol. 200, 921–927 (2016).

Steiner, C., Das, K. C., Melear, N. & Lakly, D. Reducing nitrogen loss during poultry litter composting using biochar. J Environ Qual 39, 1236–1242 (2010).

Chowdhury, M. A., de Neergaard, A. & Jensen, L. S. Potential of aeration flow rate and bio-char addition to reduce greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions during manure composting. Chemosphere 97, 16–25 (2014).

Wang, S., Zhao, X., Xing, G. & Yang, L. Large-scale biochar production from crop residue: A new idea and the biogas-energy pyrolysis system. Bioresources 8, 8–11 (2013).

Manka’abusi, D. et al. Gaseous carbon and nitrogen losses during composting of carbonized and un-carbonized agricultural residues in northern Ghana. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 181(886), 893 (2018).

Zucconi, F. Evaluating toxicity of immature compost. BioCycle 22(2), 54–57 (1981).

Peña, H., Mendoza, H., Diánez, F. & Santos, M. Parameter selection for the evaluation of compost quality. Agronomy 10(10), 1567 (2020).

Kapanen, A. & Itävaara, M. Ecotoxicity tests for compost applications. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe. 49, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1006/eesa.2000.1927 (2001).

Fuentes, A. et al. Phytotoxicity and heavy metals speciation of stabilised sewage sludges. J. Hazard Mater. 108, 161–169 (2004).

Rogovska, N., Laird, D., Cruse, R. M., Trabue, S. & Heaton, E. Germination tests for assessing biochar quality. J. Environ. Qual. 41, 1014–1022 (2012).

Jagadabhi, P. S. et al. Physico-chemical, microbial and phytotoxicity evaluation of composts from sorghum, finger millet and soybean straws. Int. J. Recyc. Org. Waste Agric. 8, 279–293 (2019).

Siles-Castellano, A. B. et al. Comparative analysis of phytotoxicity and compost quality in industrial composting facilities processing different organic wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 252, 119820 (2020).

Kutu, F. R., Mokase, T. J., Dada, O. A. & Rhode, O. H. J. Assessing microbial population dynamics, enzyme activities and phosphorus availability indices during phospho-compost production. Int. J. Recyc. Org. Waste Agric. 8, 87–97 (2019).

Awasthi, M. K. et al. Effects of biochar amendment on bacterial and fungal diversity for co-composting of gelatin industry sludge mixed with organic fraction of municipal solid waste. Bioresour. Technol. 246, 214–223 (2017).

Du, J. et al. Effects of biochar on the microbial activity and community structure during sewage sludge composting. Bioresour. Technol. 272, 171–179 (2019).

Hoogsteen, M. J. J., Lantinga, E. A., Bakker, E. J., Groot, J. C. J. & Tittonell, P. A. Estimating soil organic carbon through loss on ignition: Effects of ignition conditions and structural water loss. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 66, 320–328 (2015).

Jones, J. Benton. Jr. Kjeldahl Method for Nitrogen Determination. (Micro-Macro Publishing, Inc., Georgia, USA, 1991).

da Silva, I. J., Lavorante, A. F., Paim, A. P. & da Silva, M. J. Microwave-assisted digestion employing diluted nitric acid for mineral determination in rice by ICP OES. Food Chem. 319, 126435 (2020).

Bohacz, J. Microbial strategies and biochemical activity during lignocellulosic waste composting in relation to the occurring biothermal phases. J. Environ. Manage. 206, 1052–1062 (2018).

Tibu, C., Annang, T. Y., Solomon, N. & Yirenya-Tawiah, D. Effect of the composting process on physicochemical properties and concentration of heavy metals in market waste with additive materials in the Ga West Municipality, Ghana. Int. J. Recyc. Org. Waste Agric. 8, 393–403 (2019).

Yu, H., Xie, B., Khan, R. & Shen, G. The changes in carbon, nitrogen components and humic substances during organic-inorganic aerobic co-composting. Bioresour. Technol. 271, 228–235 (2019).

Jara-Samaniego, J. et al. Composting as sustainable strategy for municipal solid waste management in the Chimborazo Region, Ecuador: Suitability of the obtained composts for seedling production. J. Clean. Prod. 141, 1349–1358 (2017).

Mortula, M. M. et al. Sustainable management of organic wastes in Sharjah, UAE through co-composting. Methods Protoc 3, 1–12 (2020).

Anwari, G., Mandozai, A. & Feng, J. Effects of biochar amendment on soil problems and improving rice production under salinity conditions. Adv. J. Grad. Res. 7, 45–63 (2019).

Mensah, A. K. & Frimpong, K. A. Biochar and/or compost applications improve soil properties, growth, and yield of maize grown in acidic rainforest and coastal savannah soils in Ghana. Int. J. Agronom. 2018(1), 6837404 (2018).

Azim, K. et al. Composting parameters and compost quality: A literature review. Org. Agric. 8, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-017-0180-z (2018).

Nakasaki, K. & Marui, T. Progress of organic matter degradation and maturity of compost produced in a large-scale composting facility. Waste Manage. Res. 29, 574–581 (2011).

Singh, S. & Nain, L. Microorganisms in sustainable agriculture. Proc. Indian Nat. Sci. Acad. 80, 473–481 (2014).

Malinowski, M., Wolny-Koładka, K. & Vaverková, M. D. Effect of biochar addition on the OFMSW composting process under real conditions. Waste Manage. 84, 364–372 (2019).

Zhang, L. & Sun, X. Changes in physical, chemical, and microbiological properties during the two-stage co-composting of green waste with spent mushroom compost and biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 171, 274–284 (2014).

Rashad, F. M., Saleh, W. D. & Moselhy, M. A. Bioconversion of rice straw and certain agro-industrial wastes to amendments for organic farming systems: 1. Composting, quality, stability and maturity indices. Bioresour Technol 101, 5952–5960 (2010).

Lehmann, J. & Joseph, S. (Eds). Biochar for Environmental Management. (2015).

Pathy, A., Ray, J. & Paramasivan, B. Biochar amendments and its impact on soil biota for sustainable agriculture. Biochar 2(3), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-020-00063-1 (2020).

Du, Z. et al. Consecutive biochar application alters soil enzyme activities in the winter wheat-growing season. Soil Sci. 179, 75–83 (2014).

Kumar, A., Saini, K. & Bhaskar, T. Hydochar and biochar: Production, physicochemical properties and techno-economic analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 310, 123442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123442 (2020).

Yaashikaa, P. R., Kumar, P. S., Varjani, S. & Saravanan, A. J. B. R. A critical review on the biochar production techniques, characterization, stability and applications for circular bioeconomy. Biotechnol. Rep. 28, e00570 (2020).

Warnock, D. D. et al. Influences of non-herbaceous biochar on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal abundances in roots and soils: Results from growth-chamber and field experiments. Appl. Soil Ecol. 46, 450–456 (2010).

Sun, D., Lan, Y., Xu, E. G., Meng, J. & Chen, W. Biochar as a novel niche for culturing microbial communities in composting. Waste Manage. 54, 93–100 (2016).

Raj, D. & Antil, R. S. Evaluation of maturity and stability parameters of composts prepared from agro-industrial wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 2868–2873 (2011).

Godlewska, P., Schmidt, H. P., Ok, Y. S. & Oleszczuk, P. Biochar for composting improvement and contaminants reduction. Rev. Bioresour. Technol. 246, 193–202 (2017).

Jindo, K. et al. Influence of biochar addition on the humic substances of composting manures. Waste Manage. 49, 545–552 (2016).

Bustamante, M. A. et al. Use of chemometrics in the chemical and microbiological characterization of composts from agroindustrial wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 101, 4068–4074 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Ruhr University of Bochum for funding and providing laboratory space for the compost analysis; Ms. Sabine Frolich, Ms. Katja Gonschorek and Ms. Heidrun Kerkhoff for their assistance in laboratory analysis, as well as Dr. Stefanie Heinze, Dr. Michael Herre and Dr. Isaac Asirifi at the Department of Soil Science/Soil Ecology, Ruhr University, Bochum for their technical assistance and advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.A.F., B.M., D.M., and E.A.B. conceptualized and designed the study; E.A.B., D.M., and L.A. collected data; E.A.B., K.A.F., D.M., and L.A. analyzed and interpreted the results. ; E.A.B., K.A.F., B.M., D.M., and L.A. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abban-Baidoo, E., Manka’abusi, D., Apuri, L. et al. Biochar addition influences C and N dynamics during biochar co-composting and the nutrient content of the biochar co-compost. Sci Rep 14, 23781 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67884-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67884-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Composting as a pathway for organic waste valorization: substrate performance, process strategies, and quality benchmarks

Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management (2026)

-

Influence of biochar on DOM formation in chicken manure composting: spectral properties and molecular weight analysis

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2025)