Abstract

Secure multi-party computation of Chebyshev distance represents a crucial method for confidential distance measurement, holding significant theoretical and practical implications. Especially within electronic archival management systems, secure computation of Chebyshev distance is employed for similarity measurement, classification, and clustering of sensitive archival information, thereby enhancing the security of sensitive archival queries and sharing. This paper proposes a secure protocol for computing Chebyshev distance under a semi-honest model, leveraging the additive homomorphic properties of the NTRU cryptosystem and a vector encoding method. This protocol transforms the confidential computation of Chebyshev distance into the inner product of confidential computation vectors, as demonstrated through the model paradigm validating its security under the semi-honest model. Addressing potential malicious participant scenarios, a secure protocol for computing Chebyshev distance under a malicious model is introduced, utilizing cryptographic tools such as digital commitments and mutual decryption methods. The security of this protocol under the malicious model is affirmed using the real/ideal model paradigm. Theoretical analysis and experimental simulations demonstrate the efficiency and practical applicability of the proposed schemes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of cloud computing, edge computing and other new generation information technologies, the global data volume is exploding. Data has become an important strategic resource affecting global competition. However, at present, massive amounts of data are distributed across different organizational structures and information systems, and it is necessary to achieve cross departmental, cross regional, and cross system data sharing in order to fully realize the value of data. However, data security and compliance issues pose many challenges to data sharing. Secure multi-party computation (MPC), as the core technology of privacy computing, provides a breakthrough approach to ensuring the value of data under the premise of security and compliance. It is an interdisciplinary technology system covering many fields such as cryptography, artificial intelligence, and blockchain1,2,3.

Secure multi-party computation is a cryptographic technique that allows multiple parties to collaboratively compute a predetermined function without disclosing their private inputs. Specifically, suppose there are \(n\) participants, each with a secret input \(x_{i}\) (\(i = 1,2, \ldots ,n\)). They aim to jointly compute an \(n\)-ary function \(f(x_{1} ,x_{2} , \ldots ,x_{n} ) = (y_{1} ,y_{2} , \ldots ,y_{n} )\). Upon completion, each participant only obtains their output \(y_{i}\). Apart from their own input and output, and any information derivable from these, they cannot gain any additional information.

The concept of secure multi-party computation was first introduced in 1982 by computer scientist Professor Andrew Yao with the "Millionaires’ Problem"4. Subsequently, researchers such as Goldreich and others conducted extensive studies on this topic5,6,7. The research scope of secure multi-party computation has continually expanded, encompassing areas such as privacy-preserving data mining, secure computational geometry and set operations, secure scientific computation, secure statistical analysis, and secure database queries8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,25. These studies have significantly advanced the field of secure multi-party computation, addressing numerous practical problems.

The challenges and limitations of secure multi-party computation include the high computational and communication overhead due to extensive encryption and decryption operations and data transmission among participants. Designing efficient and secure multi-party computation protocols is complex, particularly for intricate functions or large numbers of participants. Different MPC protocols rely on varying trust assumptions, such as the number of participants and their behavior (semi-honest, malicious, etc.).

The development trends in secure multi-party computation indicate that, with advances in cryptography and computational power, the efficiency and practicality of MPC protocols are continuously improving. MPC is increasingly being integrated with other privacy-preserving technologies, such as differential privacy and federated learning, to offer more robust privacy protection solutions.

In summary, secure multi-party computation is a powerful tool that enables collaborative computation while ensuring data privacy. As technology progresses, its application prospects are becoming increasingly widespread.

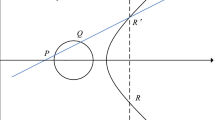

The Chebyshev distance (CD), an essential measure of distance, indicates greater dissimilarity between entities as the distance increases. It finds utility in machine learning tasks such as clustering, classification, and anomaly detection. Originating from the moves of the Chinese king in chess, the Chebyshev distance on a chessboard refers to the number of steps the king needs to move from one position to another. Given the king's ability to move one square diagonally, efficient movement towards the target square is achievable. Figure 1 illustrates all positions on the chessboard with their Chebyshev distance from position \((3,4)\). Also known as \(L \, \infty\) distance, the Chebyshev distance measures between two n-dimensional vectors, representing the maximum difference across dimensions. If points \(A(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\) and \(B(x_{2} ,y_{2} )\) represent two points, the Chebyshev distance between them is defined as:

\(d(x,y) = \max_{i} \left| {x_{i} - y_{i} } \right| = \max (\left| {x_{1} - x_{2} } \right|,\left| {y_{1} - y_{2} } \right|)\).

Here, the vector \(x\) and vector \(y\) represent two n-dimensional vectors, and \(x_{i}\) and \(y_{i}\) represent their values in the i-th dimension. For example, if there are two 2-dimensional vectors, \(x = (1,2)\) and \(y = (3,5)\), then their Chebyshev distance is defined as: \(d(x,y) = \max (\left| {1 - 3} \right|,\left| {2 - 5} \right|) = 3\). In this example, the maximum difference between the corresponding dimensions of the two vectors is 3, so their Chebyshev distance is 3.

In archival management systems, Chebyshev distance primarily serves for similarity measurement, classification, clustering of archival data, and assessing the extent of data compression and dimensionality reduction. By representing features of sensitive archival data as vectors and computing the Chebyshev distance between different data points, the similarity can be determined, aiding in information retrieval, cluster analysis, and anomaly detection. Computing the Chebyshev distance between archives facilitates grouping similar archives for classification and conducting cluster analysis to organize archives into clusters, enhancing archival management. Utilizing Chebyshev distance as a distance metric enables the evaluation of data compression and dimensionality reduction effectiveness to select optimal compression and reduction techniques for large volumes of archival data, thus conserving storage space and enhancing processing efficiency. Computing Chebyshev distance while safeguarding the privacy of sensitive archival data holds significant theoretical and practical value. Secure computation of Chebyshev distance contributes to better management and organization of archival data, improving efficiency and security in querying and sharing sensitive archives.

The key to computing Chebyshev distance securely lies in the secure computation of the absolute difference between two numbers, similar to the problem of securely computing Manhattan distance (MD). The existing Reference26 investigates the secure computation of the Manhattan distance between two points, specifically calculating the Manhattan distance \(MD = \left| {x_{1} - x_{2} } \right| + \left| {y_{1} - y_{2} } \right|\) between points \(P(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\) and \(Q(x_{2} ,y_{2} )\) under privacy protection. Protocol 1 in26 employs an encoding method and the Goldwasser-Micali public key encryption algorithm to transform the problem into the secure computation of the Hamming distance between two bit strings. Protocol 2 in26 combines another encoding method with the Paillier encryption algorithm, enabling the secure computation of the Manhattan distance while preventing malicious participants from cheating at critical stages. In27, a protocol for securely computing the absolute difference between two numbers (27-Protocol 3) is designed based on the Paillier encryption algorithm and an encoding method. This protocol serves as the foundation for a secure Manhattan distance computation protocol (27-Protocol 4). Similarly,28 constructs a secure Manhattan distance computation protocol (28-Protocol 4) using the Paillier encryption algorithm and an encoding method. For cases where the input is plaintext and the output is ciphertext,29 designs a secure absolute value output protocol (29-Protocol 4) based on the Paillier encryption algorithm. By invoking this protocol, the secure computation of the Chebyshev distance (29-Protocol 5) and the Manhattan distance (29-MD) is further addressed.

However, it is noteworthy that existing related protocols primarily involve modular exponentiation, which is time-consuming and limits computational efficiency. Additionally, existing protocols are secure under the semi-honest model, and no secure Chebyshev distance computation schemes resistant to malicious adversaries have been identified. Designing efficient and secure Chebyshev distance computation protocols remains a challenge in this field. This study aims to further advance the domain of secure geometric computation.

Contributions

-

(1)

This paper presents a novel MPC protocol for the Chebyshev distance in the semi-honest model. The proposed protocol is based on the NTRU cryptosystem and a vector encoding technique. The correctness of the protocol is rigorously analyzed, and its security in the semi-honest model is formally proven using the model paradigm.

-

(2)

In order to counteract potential malicious activities in semi-honest model protocols, the present study suggests a MPC protocol for computing the Chebyshev distance in the presence of malicious adversaries. This approach utilizes cryptographic techniques including digital commitments and a collaborative decryption method involving both parties.

-

(3)

The validity of the protocol in the presence of malicious adversaries is examined, and its security is demonstrated through the utilization of the real/ideal model paradigm, while the effectiveness of the suggested protocols is verified through a series of performance analyses, comparisons, and simulation experiments against existing approaches.

Preliminary knowledge

NTRU cryptosystem

The NTRU cryptosystem is considered to be strongly related to the shortest vector problem on the computational lattice. It can resist quantum attacks, and has high speed and security30. The NTRU cryptosystem is defined on the ring \(R = Z[X]/(X^{N} - 1)\), in which elements can be expressed in polynomial or vector form, such as

Key generation: Generate an integer triplet \((N,p,q)\) according to the given security parameter \(k\), meeting the following requirements: \(N\) is a prime number, \(\gcd (p,q) = 1\) and \(q > > p\). Then generate four sets of \((N - 1){\text{ - order}}\) integer coefficient polynomials \(L_{f} ,L_{g} ,L_{r} ,L_{m}\), meeting the following requirements: the set \(L_{m}\) selected by plaintext m is a polynomial including all modules \(p\), \(L_{m} { = }\){\(m \in R\), where the coefficient range of m is \(( - \frac{p}{2},\frac{p}{2})\)}, \(L_{f} = L(d_{f} ,d_{f} - 1)\), \(\, L_{g} = L(d_{g} ,d_{g} )\), \(L_{r} = L(d_{r} ,d_{r} )\), that is, three positive integers \(d_{f} ,d_{g} ,d_{r}\) can determine the set \(L_{f} ,L_{g} ,L_{r}\), where \(L(d_{1} ,d_{2} ) \, = \,\){\(H \in R\) where \(d_{1}\) coefficients are ‘1’, \(d_{2}\) coefficients are ‘−1’, and the remaining coefficients are ‘0’ in H}.

First, select polynomial \(f \in L_{f} ,g \in L_{g}\) at random, and there are inverse elements of \(f\) under module \(p\) and module \(q\), which are recorded as \(F_{p}\) and \(F_{q}\) respectively, then \(F_{p} * f = 1\bmod p\), \(F_{q} * f = 1\bmod q\). Calculate the public key \(h = p \cdot F_{q} * g(\bmod q)\) and private key \((f,F_{p} )\), and store \(F_{p}\), \(F_{q}\), \(g\) as private keys.

Encryption: encode the data information to be encrypted as plaintext polynomial \(M \in L_{m}\), select a random polynomial \(r \in L_{r}\), and calculate the ciphertext \(C = E(M) = r * h + M(\bmod \, q)\).

Decryption: first calculate the intermediate polynomial \(d = f * C(\bmod q)\), where the coefficient of \(d\) belongs to set \(\{ - \tfrac{q}{2},\tfrac{q}{2}\}\), and then calculate the plaintext polynomial \(M = D(C) = F_{p} * d(\bmod p)\), according to the plaintext encoding rules, the plaintext data can be obtained.

Additive homomorphism:

Security definition under the semi-honest model

Semi-honest model:

In the semi-honest model, participants strictly adhere to every step of the protocol, providing no false information, refraining from stopping midway, and not colluding with other participants to attack the protocol. However, they do record publicly available information during the protocol to attempt to infer other participants' private information31.

Relevant concepts:

-

(1)

Ideal model: this model assumes a trusted third party (TTP) to whom participants provide their inputs. The TTP computes the function according to the protocol and returns the result. The security of this model is evident as the TTP is considered entirely trustworthy and does not leak any information.

-

(2)

Real model: in this model, there is no TTP. Participants directly run the protocol, obtaining results through mutual communication and computation. The security proof in this model ensures that participants can only access information they would have obtained in the ideal model.

The objective of proving a protocol's security is to demonstrate that the execution in the real model is equivalent to the execution in the ideal model. Specifically, this means that any information a participant gains in the real model is indistinguishable from the information they would gain in the ideal model.

To achieve this, a simulator (S) is introduced, which operates in the ideal model. The simulator attempts to replicate all the information observable by an adversary (A) in the real model. A protocol is considered secure if, for any attack in the real model, the simulator can produce an output distribution in the ideal model that is computationally indistinguishable from what is observed in the real model.

Definition 1 provides a formal security definition in the semi-honest model, describing the simulation paradigm. It implies that for any potential attack in the real model, a simulator exists such that the simulator's view (all information it can observe) in the ideal model is computationally indistinguishable from the adversary's view in the real model.

Notation in Definition 1:

Assume Steven and Tom are two participants in a secure computation, where Steven holds data \(x\) and Tom holds data \(y\). They wish to cooperatively compute a probabilistic polynomial-time function \(f(x,y) = (f_{1} (x,y),f_{2} (x,y))\) while preserving the privacy of \(x\) and \(y\). Let \(\pi\) be the protocol for computing \(f\). The sequence of information obtained by Steven during the execution of protocol \(\pi\) (the view in the real model) is denoted as \(view_{1}^{\pi } (x,y) = (x,r_{1} ,m_{1}^{1} , \, \cdots { , }m_{1}^{t} ,f_{1} (x,y))\), where \(r_{1}\) represents the random numbers chosen by Steven, and \(m_{1}^{i}\) \((i = 1, \, \cdots {\text{ , t}})\) denotes the ith message received by Steven. After executing protocol \(\pi\), Steven's output is \(f_{1} (x,y)\). Tom's sequence of information is similarly defined.

Definition 1

Suppose \(f(x,y) = (f_{1} (x,y),f_{2} (x,y))\) is a two-party function, where \(x\) and \(y\) are the inputs from two participants, and \(f_{1} (x,y)\) and \(f_{2} (x,y)\) are the outputs received by each participant, respectively. Let \(\pi\) be a two-party protocol for computing \(f\). If there exist probabilistic polynomial-time simulators \(S_{1}\) and \(S_{2}\) such that:

then the protocol \(\pi\) securely computes the function \(f\). Here, \(S_{1} (x,f_{1} (x,y))\) and \(S_{2} (y,f_{2} (x,y))\) are the views of the simulators in the ideal model, and \(view_{1}^{\pi } (x,y)\) and \(view_{2}^{\pi } (x,y)\) are the views of the participants in the real model. The symbol \(\mathop \equiv \limits^{c}\) denotes computational indistinguishability.

Application of Definition 1:

-

(1)

Defining the Real Model (Designing the Protocol): Describe the protocol execution process in the real model, detailing how participants obtain results through mutual communication and computation.

-

(2)

Constructing the Simulator: For every possible adversary in the real model, construct a corresponding simulator that can mimic all potential attack behaviors in the ideal model. The simulator receives the same input as the adversary and attempts to generate a view indistinguishable from the adversary's view in the real model.

-

(3)

Proving View Equivalence: Demonstrate that for any attack in the real model, the view generated by the simulator in the ideal model is computationally indistinguishable from the adversary's view in the real model. This means the differences between the two views cannot be recognized by any polynomial-time algorithm.

Security under the malicious model

Compared to the semi-honest adversary who is expected to behave honestly during the protocol execution, the malicious adversary (also known as an active adversary) is more aggressive and capable of manipulating the corrupted parties to deviate from the protocol description in an arbitrary manner, such as sending false messages or intentionally terminating the protocol, to compromise the security of the protocol. The security model that is resilient to malicious adversaries provides strong security guarantees, ensuring that no successful attack can occur.

The security proofs for secure multi-party computation protocols under the commonly accepted malicious model are based on an ideal protocol that assumes the existence of a trusted third party (TTP)32.

Note 1: In the context of the malicious model, the security definition implies that a two-party computation protocol can only be considered feasible if at least one party is honest. It is not possible to create a secure protocol if both parties are malicious.

One-way hash function

One-way hash function is a mathematical function that transforms a message of any size into a fixed-length (usually smaller) output. The computation process of this function is irreversible, making it impossible to recover the input from the output. Moreover, even a small change in the input message will result in a completely different output, making it unpredictable. Thus, one-way hash functions are widely used as fundamental cryptographic tools33.

Given message \(x\), the computation of \(h = hash(x)\) is straightforward, on the contrary, it is difficult to find \(x\) from known \(h = hash(x)\). If a small change is made to \(x\), even just one bit, the value of \(hash(x)\) will undergo significant changes.

Digital commitment

Digital commitment is a fundamental cryptographic tool that involves two main phases: the commitment phase and the revealing phase33.

-

(1)

During the commitment phase, the committer selects a random number \(r\) based on their message \(m\), computes the commitment function \(c = c(m,r)\), and sends it to the receiver, as if sealing the message in an envelope. During this phase, no recipient, even if attempting to deceive, can gain any knowledge about the committed value \(m\) within polynomial time with high probability. This property is called hiding.

-

(2)

In the revealing phase, the committer provides the receiver with the random number \(r\) and their committed value \(m\). The receiver then computes the commitment function \(c^{\prime} = c(m,r)\) and verifies if \(c = c^{\prime}\). If it does, the commitment is considered valid; otherwise, it is rejected. This phase is akin to opening the envelope in front of the receiver. In this phase, it is required that no committer can find \(m \ne m^{\prime}\) and \(r \ne r^{\prime}\) that satisfy \(c(m,r) = c(m^{\prime},r^{\prime})\). This property is called binding.

Secure computation of Chebyshev distance under the semi-honest model

Problem description: Assuming Steven and Tom map sensitive archival data to private points \(S(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\) and \(T(x_{2} ,y_{2} )\) on a plane, they seek to securely compute the Chebyshev distance between the two points, denoted as function \(f(S,T) = \max (\left| {x_{1} - x_{2} } \right|,\left| {y_{1} - y_{2} } \right|)\), for analysis or evaluation purposes, without disclosing any information about their respective private points.

In the following context, points \(S(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\) and \(T(x_{2} ,y_{2} )\) are considered as two vectors of two-dimension.

In order to securely compute the Chebyshev distance, two encoding methods are designed as follows:

Assuming the universe is \(U = \left\{ {u_{1} , \, \cdots { ,}u_{n} } \right\}\), where \(u_{1} , \, \cdots { ,}u_{n}\) are continuous integer satisfying \(u_{1} { < } \cdots { < }u_{n}\). Assume points \(S(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\) and \(T(x_{2} ,y_{2} )\) satisfy \(x_{1} ,y_{1} ,x_{2} ,y_{2} \in U\).

Encoding method 1: Taking the encoding of \(x_{1}\) in \(S(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\) as an example, the encoding method will be introduced below. Based on \(x_{1}\) and the universe \(U\), a n-dimensional array \(A_{1} = (a_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}a_{1n} )\) is constructed as follows: Assuming \(x_{1} = u_{k}\), \(k\) in \(\{ 1, \, \cdots { , }n\}\), let the first \(k\) elements of the array be 0, and the remaining \(n - k\) elements be 1, that is, let.

For \(y_{1}\), its corresponding array is constructed in the same way and denoted as \(A_{2} = (a_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}a_{2n} )\).

Example 1

Assuming the universe is \(U = \{ 1,2,3,4,5\}\), for point \(S(2,4)\), using the Encoding method 1, encode the x-coordinate \(x_{1} = 2\) as \(A_{1} = (0,0,1,1,1)\), and encode the y-coordinate \(y_{1} = 4\) as \(A_{2} = (0,0,0,0,1)\).

Similarly, for the point \(T(1,5)\), encode \(x_{2} = 1\) as \(A^{\prime}_{1} = (0,1,1,1,1)\), and encode \(y_{2} = 5\) as \(A^{\prime}_{2} = (0,0,0,0,0)\).

Encoding method 2: Continuing with the example of encoding \(x_{1}\) in \(S(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\), construct a n-dimensional array \(B_{1} = (b_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}b_{1n} )\) based on \(x_{1}\) and the universe \(U\) as follows: Assuming \(x_{1} = u_{k}\), \(k\) in \(\{ 1, \, \cdots { , }n\}\), let the first \(k\) elements of the array be 1, and the remaining \(n - k\) elements be 0, that is, let \(b_{11} = , \, \cdots { , = }b_{1k} = 1, \, b_{1(k + 1)} = , \, \cdots { , = }b_{1n} = 0\). For \(y_{1}\), its corresponding array is constructed in the same way and denoted as \(B_{2} = (b_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}b_{2n} )\).

Example 2

Assuming the universe is \(U = \{ 1,2,3,4,5\}\), for point \(S(2,4)\), using the Encoding method 2, encode the x-coordinate \(x_{1} = 2\) as \(B_{1} = (1,1,0,0,0)\), and encode the y-coordinate \(y_{1} = 4\) as \(B_{2} = (1,1,1,1,0)\).

Similarly, for the point \(T(1,5)\), encode \(x_{2} = 1\) as \(B^{\prime}_{1} = (1,0,0,0,0)\), and encode \(y_{2} = 5\) as \(B^{\prime}_{2} = (1,1,1,1,1)\).

Encoding method 3: Assuming the universe set is \(U = \left\{ {u_{1} , \, \cdots { ,}u_{n} } \right\}\), Steven and Tom have private points \(S(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\), \(T(x_{2} ,y_{2} )\) respectively, satisfying \(x_{1} ,y_{1} ,x_{2} ,y_{2} \in U\). Under the universe set \(U\), encode \(x_{1}\) (or \(x_{2}\)) using the Encoding method 1 (or Encoding method 2) firstly, then encode \(x_{1}\) (or \(x_{2}\)) using the Encoding method 2 (or Encoding method 1) again. The corresponding vectors can be denoted as

For \(y_{1}\) and \(y_{2}\), use the same encoding methods as described above to encode them, resulting in vectors

Example 3

Assuming that \(U = \{ 1,2,3,4,5\}\) is the universal set. Based on the Encoding methods 1, 2 and the Examples 1, 2, encode \(x_{1}\),\(x_{2}\) as follows:

-

Encoding \(x_{1} = 2\) using the method 1 as \((0,0,1,1,1)\), then encoding \(x_{1} = 2\) using the method 2 as \((1,1,0,0,0)\), and let \(A = (0,0,1,1,1{,}1,1,0,0,0)\).

-

Encoding \(x_{2} = 1\) using the method 2 as \((1,0,0,0,0)\), then encoding \(x_{2} = 1\) using the method 1 as \((0,1,1,1,1)\), and let \(A = (0,0,1,1,1{,}1,1,0,0,0)\).

The following conclusion holds for the calculation of \(\left| {x_{1} - x_{2} } \right|\) and \(\left| {y_{1} - y_{2} } \right|\)26.

Proposition 1

The value of \(\left| {x_{1} - x_{2} } \right|\) is defined as the inner product of vectors \(A\) and \(B\), while the value of \(\left| {y_{1} - y_{2} } \right|\) is defined as the inner product of vectors \(A^{\prime}\) and \(B^{\prime}\), that is

\(\left| {x_{1} - x_{2} } \right| = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {(a_{ij} b_{ij} )} }\), \(\left| {y_{1} - y_{2} } \right| = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {(a^{\prime}_{ij} b^{\prime}_{ij} )} }\).

Specific protocol

Building upon the computational principles outlined above, in conjunction with the NTRU cryptosystem, this section presents a protocol for confidential computation of Chebyshev distance under the semi-honest model (Protocol 1). Algorithm 1 illustrates the computation process for Protocol 1, while Fig. 2 depicts its flowchart. The specific description of Protocol 1 is as follows:

Protocol 1: Secure computation of Chebyshev distance under the semi-honest model.

Input: Steven's private point \(S(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\), and Tom's private point \(T(x_{2} ,y_{2} )\).

Output: The Chebyshev distance value between \(S(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\) and \(T(x_{2} ,y_{2} )\), \(f(S,T) = \max (\left| {x_{1} - x_{2} } \right|,\left| {y_{1} - y_{2} } \right|)\).

Preparation: Steven constructs the vectors corresponding to \(x_{1}\) and \(y_{1}\) using the Encoding method 3, denoted as \(F = (a_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}a_{1n} {,}a_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}a_{2n} )\) and \(G = (a^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}a^{\prime}_{1n} {,}a^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}a^{\prime}_{2n} )\), respectively. Tom constructs the vectors corresponding to \(x_{2}\) and \(y_{2}\) using the Encoding method 3, denoted as \(P = (b_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}b_{1n} {,}b_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}b_{2n} )\) and \(Q = (b^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}b^{\prime}_{1n} {,}b^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}b^{\prime}_{2n} )\). Steven generates a public/private key pair using the NTRU cryptosystem and denotes it as \(pk/sk\). Then, he sends the public key \(pk\) to Tom.

-

(1)

Steven encrypts each element of the vectors \(F\) and \(G\) using the public key \(pk\), resulting in:

$$E(F) = (E(a_{11} ), \, \cdots { , }E(a_{1n} ){, }E(a_{21} ), \, \cdots { , }E(a_{2n} )),$$$$E(G) = (E(a^{\prime}_{11} ), \, \cdots { , }E(a^{\prime}_{1n} ){, }E(a^{\prime}_{21} ), \, \cdots { , }E(a^{\prime}_{2n} )),$$then sends the encrypted vectors \(E(F)\) and \(E(G)\) to Tom.

-

(2)

Tom uses his own vectors \(P\) and \(Q\), along with the encrypted vectors \(E(F)\) and \(E(G)\) received from Steven, to perform the following calculations:

$$W_{1} = (E(a_{11} )b_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}E(a_{1n} )b_{1n} {, }E(a_{21} )b_{21} , \, \cdots { , }E(a_{2n} )b_{2n} ),$$$$W_{2} = (E(a^{\prime}_{11} )b^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}E(a^{\prime}_{1n} )b^{\prime}_{1n} {, }E(a^{\prime}_{21} )b^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { , }E(a^{\prime}_{2n} )b^{\prime}_{2n} ).$$Then, Tom randomly permutes \(2n\) elements of the vectors \(W_{1}\), \(W_{2}\), resulting in new vectors denoted as \(\hat{W}_{1}\), \(\hat{W}_{2}\), respectively, and sends the \(\hat{W}_{1}\), \(\hat{W}_{2}\) to Steven.

-

(3)

Steven decrypts \(\hat{W}_{1}\) and \(\hat{W}_{2}\) (decrypting each element separately), obtaining:

$$D(\hat{W}_{1} ) = (d_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}d_{1n} ,d_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}d_{2n} ),$$$$D(\hat{W}_{2} ) = (d^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}d^{\prime}_{1n} ,d^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}d^{\prime}_{2n} ).$$

Steven calculates

Let \(f(S,T) = \max (z_{1} ,z_{2} )\) and publishes \(f(S,T)\).

Protocol 1 ends.

Scheme analysis

Correctness analysis: In step (2) of the protocol, using the additive homomorphism of the NTRU cryptosystem, it can be deduced that

Similarly, \(E(a^{\prime}_{ij} )b^{\prime}_{ij} = E(a^{\prime}_{ij} b^{\prime}_{ij} )\). It can also be deduced that

Since \(\hat{W}_{1}\) and \(\hat{W}_{2}\) are obtained by randomly permuting the elements of \(W_{1}\) and \(W_{2}\), it follows that \(D(\hat{W}_{1} )\) and \(D(\hat{W}_{2} )\) are also obtained by permuting the elements of \(D(W_{1} )\) and \(D(W_{2} )\) accordingly. Thus,

According to the Proposition 1, it is proven that \(y_{1} = \left| {x_{1} - x_{2} } \right|\) and \(y_{2} = \left| {y_{1} - y_{2} } \right|\). Thus, the Protocol 1 has been proven to be correct.

Security analysis: Protocol 1's security is proven by the following theorem.

Theorem 1

Protocol 1 securely computes the Chebyshev distance.

Proof

To establish this theorem, construct simulators \(S_{1}\) and \(S_{2}\) that satisfy Eqs. (1) and (2).

The simulation process of \(S_{1}\) is as follows:

-

(1)

After receiving inputs \((x_{1} ,f_{1} (x_{1} ,x_{2} ))\) and \((y_{1} ,f_{1} (y_{1} ,y_{2} ))\), the simulator randomly selects \(x^{\prime}_{2} \in U\) and \(y^{\prime}_{2} \in U\) such that \(f_{1} (x_{1} ,x^{\prime}_{2} ) = f_{1} (x_{1} ,x_{2} )\) and \(f_{1} (y_{1} ,y^{\prime}_{2} ) = f_{1} (y_{1} ,y_{2} )\), encodes \(x_{1}\), \(x^{\prime}_{2}\), \(y_{1}\), \(y^{\prime}_{2}\) using the coding method 3 to obtain the corresponding vectors

$$F = (a_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}a_{1n} {,}a_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}a_{2n} ),$$$$P^{\prime} = (b^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}b^{\prime}_{1n} {,}b^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}b^{\prime}_{2n} )$$and

$$G = (a^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}a^{\prime}_{1n} {,}a^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}a^{\prime}_{2n} )$$$$Q^{\prime} = (b^{\prime \prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}b^{\prime \prime}_{1n} {,}b^{\prime \prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}b^{\prime \prime}_{2n} )$$ -

(2)

\(S_{1}\) encrypts vectors \(F\), \(G\) to obtain \(E(F)\), \(E(G)\), and computing

$$W^{\prime}_{1} = (E(a_{11} )b^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}E(a_{1n} )b^{\prime}_{1n} {, }E(a_{21} )b^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { , }E(a_{2n} )b^{\prime}_{2n} ),$$$$W^{\prime}_{2} = (E(a^{\prime}_{11} )b^{\prime \prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}E(a^{\prime}_{1n} )b^{\prime \prime}_{1n} {, }E(a^{\prime}_{21} )b^{\prime \prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { , }E(a^{\prime}_{2n} )b^{\prime \prime}_{2n} ),$$followed by randomly permuting the elements of \(W^{\prime}_{1}\), \(W^{\prime}_{2}\) to obtain \(\hat{W^{\prime}}_{1}\), \(\hat{W}^{\prime}_{2}\).

-

(3)

\(S_{1}\) decrypts \(\hat{W^{\prime}}_{1}\), \(\hat{W}^{\prime}_{2}\) to obtain \(D(\hat{W}^{\prime}_{1} )\), \(D(\hat{W}^{\prime}_{2} )\).

-

(4)

\(S_{1}\) computes \(z^{\prime}_{1}\),\(z^{\prime}_{2}\) and sets

$$f^{\prime}(S,T) = \max (z^{\prime}_{1} ,z^{\prime}_{2} ).$$

During the execution of the protocol,

while

\(\hat{W}_{1}\), \(\hat{W}_{2}\) are obtained by Tom through randomly permutating \(2n\) elements in \(W_{1}\), \(W_{2}\) and sending them to Steven. Although Steven has the private key \(sk\) to decrypt \(\hat{W}_{1}\) and \(\hat{W}_{2}\), Steven can only know the decrypted vectors \(D(\hat{W}_{1} )\) and \(D(\hat{W}_{2} )\) (which consist of 0 s and 1 s), but cannot determine which ciphertext corresponds to 0 or 1 in \(W_{1}\) and \(W_{2}\). Therefore, \(\hat{W}_{1} \, \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} \, \hat{W}^{\prime}_{1}\) and \(\hat{W}_{2} \, \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} \, \hat{W}^{\prime}_{2}\). Furthermore, due to \(f_{1} (x_{1} ,x^{\prime}_{2} ) = f_{1} (x_{1} ,x_{2} )\) and \(f_{1} (y_{1} ,y^{\prime}_{2} ) = f_{1} (y_{1} ,y_{2} )\), so

The following describes the execution process of simulating \(S_{2}\).

-

(1)

After receiving the input of \((x_{2} ,f_{2} (x_{1} ,x_{2} ))\) and \((y_{2} ,f_{2} (y_{1} ,y_{2} ))\), \(S_{2}\) randomly choose \(x^{\prime}_{1} \in U\) and \(y^{\prime}_{1} \in U\), such that \(f_{2} (x^{\prime}_{1} ,x_{2} ) = f_{2} (x_{1} ,x_{2} )\) and \(f_{2} (y^{\prime}_{1} ,y_{2} ) = f_{2} (y_{1} ,y_{2} )\). Encode \(x^{\prime}_{1}\), \(x_{2}\), \(y^{\prime}_{1}\), \(y_{2}\) using the encoding method 3, resulting in respective vectors

$$F^{\prime} = (a^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}a^{\prime}_{1n} {,}a^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}a^{\prime}_{2n} ),$$$$P = (b_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}b_{1n} {,}b_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}b_{2n} ),$$and

$$G^{\prime} = (a^{\prime \prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}a^{\prime \prime}_{1n} {,}a^{\prime \prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}a^{\prime \prime}_{2n} ),$$$$Q = (b^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}b^{\prime}_{1n} {,}b^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}b^{\prime}_{2n} ).$$(2) \(S_{2}\) encrypts the vectors \(F^{\prime}\), \(G^{\prime}\) to obtain \(E(F^{\prime})\), \(E(G^{\prime})\), and calculates

$$W^{\prime}_{1} = (E(a^{\prime}_{11} )b_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}E(a^{\prime}_{1n} )b_{1n} {, }E(a^{\prime}_{21} )b_{21} , \, \cdots { , }E(a^{\prime}_{2n} )b_{2n} ),$$$$W^{\prime}_{2} = (E(a^{\prime \prime}_{11} )b^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}E(a^{\prime \prime}_{1n} )b^{\prime}_{1n} {, }E(a^{\prime \prime}_{21} )b^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { , }E(a^{\prime \prime}_{2n} )b^{\prime}_{2n} ).$$Then randomly permute the elements of \(W^{\prime}_{1}\), \(W^{\prime}_{2}\) to obtain \(\hat{W^{\prime}}_{1}\), \(\hat{W}^{\prime}_{2}\).

(3) \(S_{2}\) decrypts \(\hat{W^{\prime}}_{1}\), \(\hat{W}^{\prime}_{2}\) to obtain \(D(\hat{W}^{\prime}_{1} )\), \(D(\hat{W}^{\prime}_{2} )\).

(4) \(S_{2}\) calculates \(z^{\prime}_{1}\), \(z^{\prime}_{2}\), and let \(f^{\prime}(S,T) = \max (z^{\prime}_{1} ,z^{\prime}_{2} )\). During the execution of the protocol,

$$view_{2}^{\pi } (x_{1} ,x_{2} ) = \{ x_{2} ,E(F),f_{2} (x_{1} ,x_{2} )\} ,$$$$view_{2}^{\pi } (y_{1} ,y_{2} ) = \{ y_{2} ,E(G),f_{2} (y_{1} ,y_{2} )\} ,$$and

$$S_{2} (x_{2} ,f_{2} (x_{1} ,x_{2} )) = \{ x_{2} ,E(F^{\prime}),f_{2} (x^{\prime}_{1} ,x_{2} )\} ,$$$$S_{2} (y_{2} ,f_{2} (y_{1} ,y_{2} )) = \{ y_{2} ,E(G^{\prime}),f_{2} (y^{\prime}_{1} ,y_{2} )\} .$$\(E(F)\) and \(E(G)\) are encrypted using the NTRU cryptosystem by Steven. Tom does not have the private key. Based on the semantic security of the NTRU cryptosystem, it can be concluded that for Tom, \(E(F) \, \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} \, E(F^{\prime})\), \(E(G) \, \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} \, E(G^{\prime})\), and due to \(f_{2} (x^{\prime}_{1} ,x_{2} ) = f_{2} (x_{1} ,x_{2} )\), \(f_{2} (y^{\prime}_{1} ,y_{2} ) = f_{2} (y_{1} ,y_{2} )\),

$$\{ S_{2} (x_{2} ,f_{2} (x_{1} ,x_{2} ))\}_{{(x_{1} ,x_{2} )}} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} \, \{ view_{2}^{\pi } (x_{1} ,x_{2} )\}_{{(x_{1} ,x_{2} )}} ,$$$$\{ S_{2} (y_{2} ,f_{2} (y_{1} ,y_{2} ))\}_{{(y_{1} ,y_{2} )}} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} \, \{ view_{2}^{\pi } (y_{1} ,y_{2} )\}_{{(y_{1} ,y_{2} )}} .$$Therefore, Protocol 1 securely computes the Chebyshev distance.

Secure computation of Chebyshev distance under the malicious model

In the Protocol 1, malicious behaviors that a malicious participant may carry out include: (1) In step (2) of the Protocol 1, participant Tom may provide false ciphertext to Steven. (2) One participant may possess both the public and private keys, while the other participant can only passively wait for the result. There may be a possibility of the participant with the keys providing incorrect results to the other participant. In step (3), Steven may inform Tom of incorrect results, preventing Tom from obtaining the correct result.

Solution:

-

(1)

Both parties need to possess public and private keys. In the protocol, the computation result is decrypted by Steven and Tom respectively to obtain the Chebyshev distance, ensuring both parties accurately compute the result.

-

(2)

Design a MPC protocol for anti-deception scenarios by combining the NTRU cryptosystem with digital commitment methods, ensuring that both participants obtain the same computation result (if one party attempts to deceive, the other party can detect it). The so-called digital commitment can be understood as a two-stage protocol involving two parties, namely the committer and the receiver. Through this protocol, the committer can bind themselves to a number. This binding must satisfy confidentiality and determinism. Confidentiality means that after the committer makes a commitment, the receiver cannot obtain any knowledge about the committed number; determinism means that the receiver only accepts the legitimate number sent by the committer, and can detect and reject it if the committer attempts to deceive.

Specific protocol

The specific protocol under the malicious model (Protocol 2) is described below. Algorithm 2 illustrates the computation process for Protocol 2, while Fig. 3 depicts its flowchart.

Protocol 2: Secure computation of Chebyshev distance under the malicious model

Input: Steven's private point \(S(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\), Tom's private point \(T(x_{2} ,y_{2} )\).

Output: The Chebyshev distance value between \(S(x_{1} ,y_{1} )\) and \(T(x_{2} ,y_{2} )\), \(f(S,T) = \max (\left| {x_{1} - x_{2} } \right|,\left| {y_{1} - y_{2} } \right|)\).

Preparation: Steven constructs the vectors corresponding to \(x_{1}\) and \(y_{1}\) using the Encoding method 3, denoted as \(F = (a_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}a_{1n} {,}a_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}a_{2n} )\) and \(G = (a^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}a^{\prime}_{1n} {,}a^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}a^{\prime}_{2n} )\), respectively. Tom constructs the vectors corresponding to \(x_{2}\) and \(y_{2}\) denoted as \(P = (b_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}b_{1n} {,}b_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}b_{2n} )\) and \(Q = (b^{\prime}_{11} , \, \cdots { ,}b^{\prime}_{1n} {,}b^{\prime}_{21} , \, \cdots { ,}b^{\prime}_{2n} )\). Both parties agree on a hash function \(Hash\). Steven generates a public/private key pair using the NTRU cryptosystem and denotes it as \(pk_{1} /sk_{1}\), then sends the public key \(pk_{1}\) to Tom. Tom generates a public/private key pair using the NTRU cryptosystem and denotes it as \(pk_{2} /sk_{2}\), then sends the public key \(pk_{2}\) to Steven.

-

(1)

Steven encrypts each element in the vectors \(F\), \(G\) with the public key \(pk_{1}\), resulting in:

$$E_{{pk_{1} }} (F) = (E(a_{11} ), \, \cdots { , }E(a_{1n} ){, }E(a_{21} ), \, \cdots { , }E(a_{2n} )),$$$$E_{{pk_{1} }} (G) = (E(a^{\prime}_{11} ), \, \cdots { , }E(a^{\prime}_{1n} ){, }E(a^{\prime}_{21} ), \, \cdots { , }E(a^{\prime}_{2n} )),$$and sends \(E_{{pk_{1} }} (F)\), \(E_{{pk_{1} }} (G)\) to Tom.

-

(2)

Tom encrypts each element in the vectors \(P\),\(Q\) with the public key \(pk_{2}\), resulting in:

$$E_{{pk_{2} }} (P) = (E(b_{11} ), \, \cdots { , }E(b_{1n} ){, }E(b_{21} ), \, \cdots { , }E(b_{2n} )),$$$$E_{{pk_{2} }} (Q) = (E(b^{\prime}_{11} ), \, \cdots { , }E(b^{\prime}_{1n} ){, }E(b^{\prime}_{21} ), \, \cdots { , }E(b^{\prime}_{2n} ))$$and sends \(E_{{pk_{2} }} (P)\), \(E_{{pk_{2} }} (Q)\) to Steven.

-

(3)

Steven chooses random numbers \(s_{1}\), \(s_{2}\), and calculates \(h_{1} = Hash(s_{1} )\), \(h_{2} = Hash(s_{2} )\). Further, Steven calculates

$$W_{1} = \left( {\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{2} }} (b_{ij} )} \, a_{ij} } } \right)s_{1} ,\quad W_{2} = \left( {\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{2} }} (b^{\prime}_{ij} )} \, a^{\prime}_{ij} } } \right)s_{2} ,$$and sends \(h_{1}\), \(h_{2}\), \(W_{1}\), \(W_{2}\) to Tom.

-

(4)

Tom chooses random numbers \(t_{1}\), \(t_{2}\), and calculates \(h_{3} = Hash(t_{1} )\), \(h_{4} = Hash(t_{2} )\). Further, Tom calculates

$$W_{3} = (\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{1} }} (a_{ij} )} \, b_{ij} )t_{1} } ,\quad W_{4} = (\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{1} }} (a^{\prime}_{ij} )} \, b^{\prime}_{ij} )t_{2} }$$and sends \(h_{3}\), \(h_{4}\), \(W_{3}\), \(W_{4}\) to Steven.

-

(5)

Steven decrypts \(W_{3}\), \(W_{4}\) to obtain \(w_{3} = D(W_{3} )\), \(w_{4} = D(W_{4} )\), and sends \(w_{3}\), \(w_{4}\) to Tom.

-

(6)

Tom decrypts \(W_{1}\), \(W_{2}\) to obtain \(w_{1} = D(W_{1} )\), \(w_{2} = D(W_{2} )\), and sends \(w_{1}\), \(w_{2}\) to Steven.

-

(7)

Steven calculates \(z_{1} = w_{1} /s_{1}\), \(z_{2} = w_{2} /s_{2}\) and sends \(z_{1}\), \(z_{2}\) to Tom.

-

(8)

Tom calculates \(z_{3} = w_{3} /t_{1}\), \(z_{4} = w_{4} /t_{2}\) and sends \(z_{3}\), \(z_{4}\) to Steven.

-

(9)

Steven verifies if \(Hash(w_{3} {\text{/z}}_{3} \, ) = h_{3}\) and \(Hash(w_{4} {\text{/z}}_{4} \, ) = h_{4}\) hold. If not, Steven refuses to accept \(z_{3}\) and \(z_{4}\). If they hold, Steven sets \(f_{1} (S,T) = \max (z_{3} ,z_{4} )\) and publishes it.

-

(10)

Tom verifies if \(Hash(w_{1} {\text{/z}}_{1} \, ) = h_{1}\) and \(Hash(w_{2} {\text{/z}}_{2} \, ) = h_{2}\) hold. If not, Tom refuses to accept \(z_{1}\) and \(z_{2}\). If they hold, Tom sets \(f_{2} (S,T) = \max (z_{1} ,z_{2} )\) and publishes it.

-

(11)

If \(f_{1} (S,T) = f_{2} (S,T)\), it proves that the computed result is correct; otherwise, it proves that the computed result is incorrect.

Protocol 2 ends.

Scheme analysis

Correctness analysis:

-

(1)

In step (3) and step (4), combining with the additive homomorphism property of the NTRU cryptosystem, it is known that:

$$(\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{2} }} (b_{ij} )} \, a_{ij} )s_{1} } = (\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{2} }} (b_{ij} a_{ij} )} {)}s_{1} \, } ,$$$$(\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{2} }} (b^{\prime}_{ij} )} \, a^{\prime}_{ij} )s_{2} = (\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{2} }} (b^{\prime}_{ij} a^{\prime}_{ij} )} \, )s_{2} } } ,$$$$(\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{1} }} (a_{ij} )} \, b_{ij} )t_{1} = (\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{1} }} (a_{ij} b_{ij} )} \, )t_{1} } } ,$$$$(\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{1} }} (a^{\prime}_{ij} )} \, b^{\prime}_{ij} )t_{2} } = (\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {E_{{pk_{1} }} (a^{\prime}_{ij} b^{\prime}_{ij} )} \, )t_{2} } .$$ -

(2)

In step (5) and step (6), Steven decrypts \(W_{3}\), \(W_{4}\) and obtains \(w_{3} = (\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {a_{ij} } \, b_{ij} )} t_{1}\), \(w_{4} = (\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {a^{\prime}_{ij} } \, b^{\prime}_{ij} )} t_{2}\), while Tom decrypts \(W_{1}\), \(W_{2}\) and obtains \(w_{1} = (\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {b_{ij} } \, a_{ij} } )s_{1}\), \(w_{2} = (\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {b^{\prime}_{ij} } \, a^{\prime}_{ij} )} s_{2}\). From Steven's calculation in step (7), it is known that \(z_{1} = w_{1} /s_{1} = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {b_{ij} } \, a_{ij} }\),\(z_{2} = w_{2} /s_{2} = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {b^{\prime}_{ij} } \, a^{\prime}_{ij} }\); from Tom's calculation in step (8), it is known that \(z_{3} = w_{3} /t_{1} = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {a_{ij} } \, b_{ij} }\), \(z_{4} = w_{4} /t_{2} = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{2} {\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{n} {a^{\prime}_{ij} } \, b^{\prime}_{ij} }\). Therefore, according to the Proposition 1, the correctness is proved.

Security analysis and proof:

In the Protocol 2, Steven and Tom decrypt the results separately, thus avoiding malicious tampering of results by either party. To prevent malicious behavior by participants, in step (3) of the protocol, Steven has sent the \(Hash\) values \(h_{1}\) and \(h_{2}\) of random numbers \(s_{1}\) and \(s_{2}\) to Tom, thus committing to \(W_{1}\) and \(W_{2}\); in step (4), Tom has sent the \(Hash\) values \(h_{3}\) and \(h_{4}\) of random numbers \(t_{1}\) and \(t_{2}\) to Steven, thus committing to \(W_{3}\) and \(W_{4}\). Participants are compelled to only disclose the actual results at the end, as per the one-way property of a hash function. This property implies that while it is simple to compute the hash value from a message, it is computationally unfeasible to reverse the process and derive the original message from the hash value. If Steven wants to modify the results, Tom will detect Steven's deception during the verification of \(Hash(w_{1} {\text{/z}}_{1} \, ) = h_{1}\) and \(Hash(w_{2} {\text{/z}}_{2} \, ) = h_{2}\) in step (10); if Tom wants to modify the results, Steven will detect Tom's deception during the verification of \(Hash(w_{3} {\text{/z}}_{3} \, ) = h_{3}\) and \(Hash(w_{4} {\text{/z}}_{4} \, ) = h_{4}\) in step (9). Therefore, the use of digital commitments ensures the security of Protocol 2. Moreover, to ensure the correctness of the computation, each participant decrypts the received results independently and verifies them at the end of the protocol, thereby guaranteeing that both parties obtain the same computation results.

The security of the Protocol 2 is further demonstrated using the real/ideal model paradigm32.

Theorem 2

The Protocol 2 (represented by \(\Pi\)) is secure under the malicious model.

Proof

For a protocol \(\Pi\) to securely compute a function \(F\), the strategies of the participants in the actual protocol, denoted as \(\overline{A} = (A_{1} ,A_{2} )\), must be indistinguishable from the strategies of the participants in the ideal model, denoted as \(\overline{B} = (B_{1} ,B_{2} )\). If this condition is satisfied, the protocol can be proven to be secure.

In the protocol, at least one party of \(A_{1}\) or \(A_{2}\) is honest, so there are two cases to consider:

Case 1: \(A_{1}\) is honest, \(A_{2}\) is dishonest.

In the case where \(A_{1}\) is honest, during the execution of the protocol \(\Pi\), there exists:

When \(A_{1}\) is honest, he will faithfully execute the protocol, which determines \(B_{1}\). What needs to be proven is the indistinguishability between the strategies \(A_{2}\) of the actual model and \(B_{2}\) of the ideal model . Therefore, it is necessary to find outputs of the strategy pairs \(\overline{B} = (B_{1} ,B_{2} )\) in the ideal model that are indistinguishable from \(REAL_{{_{{\Pi ,\mathop A\limits^{-\!\!-} (S,T)}} }}\) in the actual model. During the execution of the protocol, the actual executor is \(A_{2}\), and the verification of the correctness of the protocol should be based on the behavior \(A_{2} (T)\) of \(A_{2}\).

-

(1)

In the actual protocol, since \(A_{1}\) is an honest party, \(B_{1}\) is honest, it will faithfully mimic the behavior of \(A_{1}\) and send the true information \(S\) to the Trusted Third Party (TTP).

-

(2)

In the actual protocol, since \(A_{2}\) is dishonest, \(B_{2}\) is dishonest, and the information sent to the TTP will depend on the strategy of \(B_{2}\), which is the same as the strategy of \(A_{2}\). Therefore, the input information sent by \(B_{2}\) to the TTP is \(A_{2} (T)\).

-

(3)

The Trusted Third Party (TTP) acquires the input information \((S,A_{2} (T))\), and calculates \(F(S,A_{2} (T))\).

-

(4)

\(B_{2}\) obtains \(F(S,A_{2} (T))\) from the TTP, utilizes \(F(S,A_{2} (T))\) to obtain \(view_{{B_{2} }}^{F} (S,A_{2} (T))\), which is indistinguishable from the \(view_{{A_{2} }}^{\prod } (S,A_{2} (T))\) obtained by \(A_{2}\) when executing the actual protocol, and provides \(view_{{B_{2} }}^{F} (S,A_{2} (T))\) to \(A_{2}\), obtaining the output of \(A_{2}\). Then the simulator \(B_{2}\) simulates the protocol based on its input and assumes that the other party's input values satisfy the result, i.e., \(B_{2}\) selects \(S^{\prime}\) to simulate the protocol, and makes \(F(S^{\prime},A_{2} (T)) = F(S,A_{2} (T))\). The specific execution process of \(B_{2}\) is as follows:

-

①

\(B_{2}\) sends the required information \(E^{\prime}_{{pk_{1} }} (F)\) and \(E^{\prime}_{{pk_{1} }} (G)\) to \(A_{2}\) in step (1).

-

②

\(B_{2}\) calculates \(h^{\prime}_{1}\), \(h^{\prime}_{2}\) in step (3), and sends \(W^{\prime}_{1}\), \(W^{\prime}_{2}\) to \(A_{2}\).

-

③

\(B_{2}\) decrypts \(W^{\prime}_{3}\), \(W^{\prime}_{4}\) in step (5), and sends the decryption results \(w^{\prime}_{3}\), \(w^{\prime}_{4}\) to \(A_{2}\).

-

④

\(B_{2}\) calculates and publishes \(z^{\prime}_{1}\), \(z^{\prime}_{2}\) in step (7).

-

⑤

\(B_{2}\) verifies \(Hash(w^{\prime}_{3} {{/{\text z}^{\prime}}}_{3} \, ) = h^{\prime}_{3}\) and \(Hash(w^{\prime}_{4} {{/{\rm z}^{\prime}}}_{4} \, ) = h^{\prime}_{4}\) in step (9), then publishes \(f_{1} (S^{\prime},T) = \max (z^{\prime}_{3} ,z^{\prime}_{4} )\).

\(B_{2}\) uses \((E^{\prime}_{{pk_{1} }} (F),E^{\prime}_{{pk_{1} }} (G),W^{\prime}_{1} ,W^{\prime}_{2} ,z^{\prime}_{1} ,z^{\prime}_{2} )\) to call \(A_{2}\), outputs \(A_{2} (E^{\prime}_{{pk_{1} }} (F),E^{\prime}_{{pk_{1} }} (G),W^{\prime}_{1} ,W^{\prime}_{2} ,z^{\prime}_{1} ,z^{\prime}_{2} )\), then obtains:

In the protocol, since the NTRU cryptosystem with additive homomorphism is used, \(E_{{pk_{1} }} (F)\mathop \equiv \limits^{c} E^{\prime}_{{pk_{1} }} (F)\) and \(E_{{pk_{1} }} (G)\mathop \equiv \limits^{c} E^{\prime}_{{pk_{1} }} (G)\), the digital commitment ensures that \(W_{1} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} W^{\prime}_{1}\), \(W_{2} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} W^{\prime}_{2}\), \(z_{1} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} z^{\prime}_{1}\), \(z_{2} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} z^{\prime}_{2}\) then:

Case 2: \(A_{1}\) is dishonest, \(A_{2}\) is honest.

In this case, there are two possible scenarios:

-

(1)

If Steven ignores TTP after obtaining the information, TTP will send the terminating symbol \(\bot\) to Tom, then:

$$REAL_{{\Pi ,\mathop A\limits^{-\!\!-} }} (S,T) = \{ A_{1} (E_{{pk_{2} }} (P),E_{{pk_{2} }} (Q),W_{3} ,W_{4} ,z_{3} ,z_{4} ), \bot \} .$$ -

(2)

Otherwise, if Steven reveals the result and provides proof using digital commitment, TTP will send \(F(A_{1} (S),T)\) to Tom, then:

$$REAL_{{\Pi ,\mathop A\limits^{-\!\!-} }} (S,T) = \{ A_{1} (E_{{pk_{2} }} (P),E_{{pk_{2} }} (Q),W_{3} ,W_{4} ,z_{3} ,z_{4} ),F(A_{1} (S),T)\} .$$

Because \(A_{2}\) is honest, \(A_{2}\) will faithfully execute the protocol, and \(B_{2}\) is determined. The goal is to prove the indistinguishability between \(A_{1}\) in the actual protocol and \(B_{1}\) under the ideal model, in order to find a strategy for the ideal model's strategy pair \(\overline{B} = (B_{1} ,B_{2} )\) whose output is indistinguishable from \(REAL_{{\Pi ,\mathop A\limits^{-\!\!-} (x_{k} ,y_{k} )}}\) in the actual model. During the protocol execution, the actual executor is \(A_{1}\), so the verification of protocol correctness during the proof process must be based on the behavior \(A_{1} (S)\) of \(A_{1}\).

-

(1)

In the actual protocol, \(A_{1}\) is dishonest, so \(B_{1}\) is also dishonest. The information sent to the TTP depends on the strategy of \(B_{1}\), and the strategy of \(B_{1}\) is the same as the strategy of \(A_{1}\). Therefore, \(B_{1}\) will send \(A_{1} (S)\) to TTP.

-

(2)

In the actual protocol, \(A_{2}\) is honest, so \(B_{2}\) is also honest. The true input information \(T\) is sent to the TTP.

-

(3)

The Trusted Third Party (TTP) acquires the input information \((A_{1} (S),T)\), and computes \(F(A_{1} (S),T)\).

-

(4)

\(B_{1}\) uses the \(F(A_{1} (S),T)\) obtained from the TTP to obtain \(view_{{B_{1} }}^{F} (A_{1} (S),T)\) which should be computationally indistinguishable from \(view_{{A_{1} }}^{\prod } (A_{1} (S),T)\) obtained when \(A_{1}\) executes the actual agreement, and delivers \(view_{{B_{1} }}^{F} (A_{1} (S),T)\) to \(A_{1}\), obtaining the output of \(A_{1}\). Then, \(B_{1}\) assumes the input of the counterparty that satisfies the result based on his own input and the computed result, that is, \(B_{1}\) selects \(T^{\prime}\) to simulate the protocol and makes \(F(A_{1} (S),T^{\prime}) = F(A_{1} (S),T)\) The specific execution process of \(B_{1}\) is as follows:

-

①

\(B_{1}\) sends the required information \(E^{\prime}_{{pk_{2} }} (P)\) and \(E^{\prime}_{{pk_{2} }} (Q)\) to \(A_{1}\) in step (2).

-

②

\(B_{1}\) calculates \(h^{\prime}_{3}\), \(h^{\prime}_{4}\) in step (4) of the protocol, and then sends \(W^{\prime}_{3}\), \(W^{\prime}_{4}\) to \(A_{1}\).

-

③

\(B_{1}\) decrypts \(W^{\prime}_{1}\), \(W^{\prime}_{2}\) in step (6) of the protocol, and sends the decryption results \(w^{\prime}_{1}\), \(w^{\prime}_{2}\) to \(A_{1}\).

-

④

\(B_{1}\) calculates and publishes \(z^{\prime}_{3}\), \(z^{\prime}_{4}\) in step (8).

-

⑤

\(B_{1}\) verifies \(Hash(w^{\prime}_{1} {{/{\rm z}^{\prime}}}_{1} \, ) = h^{\prime}_{1}\) and \(Hash(w^{\prime}_{2} {{/{\rm z}^{\prime}}}_{2} \, ) = h^{\prime}_{2}\) in step (10), then publishes \(f_{2} (S,T^{\prime}) = \max (z^{\prime}_{1} ,z^{\prime}_{2} )\).

-

①

There are two possible scenarios that may occur during the execution of the protocol by \(B_{1}\):

-

(1)

If \(A_{1}\) decides not to interact with TTP after obtaining the information, then the outcome is:

$$IDEAL_{{F,\mathop B\limits^{-\!\!-} }} (S,T) = \{ A_{1} (E^{\prime}_{{pk_{2} }} (P),E^{\prime}_{{pk_{2} }} (Q),W^{\prime}_{3} ,W^{\prime}_{4} ,z^{\prime}_{3} ,z^{\prime}_{4} ), \bot \} .$$ -

(2)

Otherwise, the outcome is:

$$IDEAL_{{F,\mathop B\limits^{-\!\!-} }} (S,T) = \{ A_{1} (E^{\prime}_{{pk_{2} }} (P),E^{\prime}_{{pk_{2} }} (Q),W^{\prime}_{3} ,W^{\prime}_{4} ,z^{\prime}_{3} ,z^{\prime}_{4} ),F(A_{1} (S),T^{\prime})\} .$$

Regardless of the scenario, the outputs of \(A_{2}\) and \(B_{2}\) in the actual protocol and the ideal model protocol are the same. It is sufficient to prove that

are computationally indistinguishable. In the protocol, due to the use of NTRU cryptosystem with additive homomorphism,

the digital commitment ensures \(W_{3} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} W^{\prime}_{3}\), \(W_{4} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} W^{\prime}_{4}\), \(z_{3} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} z^{\prime}_{3}\), \(z_{4} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} z^{\prime}_{4}\). Therefore,

\(\{ IDEAL_{{F,\mathop B\limits^{-\!\!-} }} (S,T)\} \mathop \equiv \limits^{c} \{ REAL_{{\Pi ,\mathop A\limits^{-\!\!-} }} (S,T)\} .\)

In conclusion, for any acceptable polynomial-time strategy pair \(\overline{A} = (A_{1} ,A_{2} )\) in the actual protocol, there exists a polynomial-time strategy pair \(\overline{B} = (B_{1} ,B_{2} )\) in the ideal model that is acceptable and indistinguishable in computation between

thus making Protocol 2 secure under malicious model.

Performance analysis and comparison of the protocols

Computation complexity analysis

In the following text, \(n\) denotes the number of elements in the universal set \(U\), \(M_{e}\) represents modular exponentiation, and \(M_{p}\) represents modular multiplication.

In the Protocol 1 of Reference26, the Goldwasser-Micali encryption algorithm is used for encryption and decryption. One party performs \(2n\) encryption operations times, and \(2n\) decryption operations times. The other party needs to perform \(2n\) encryption operations and \(2n\) modular multiplication operations. One encryption operation requires 2 modular multiplication operations, and one decryption operation requires \(\lg p\) modular multiplications. Therefore, the Protocol 1 of26 requires \(10n + 2n\lg p\) modular multiplication operations.

In the Protocol 2 of26, the Paillier encryption algorithm is used for encryption and decryption. One party performs \(4n\) encryption operations times, and decryption operation 1 time. The other party needs to perform up to \(4n\) modular multiplication operations. Therefore, the Protocol 2 of26 requires \(2(6n + 1)\) modular multiplication operations.

Protocols 3 and 4 in27 employ the Paillier encryption algorithm for encryption and decryption. Protocol 3 requires \(2n + 3\) modular exponentiations, while Protocol 4 requires \(4n + 3\) modular exponentiations.

Protocol 4 in28, also utilizing the Paillier encryption algorithm, necessitates \(2n + 1\) encryptions and one decryption, totaling \(2n + 3\) modular exponentiations.

Protocol 5 and the MD protocol in29, both using the Paillier encryption algorithm, require 14 and 18 modular exponentiations, respectively.

The computational complexity of Protocol 1: The NTRU cryptosystem is used in the Protocol 1 of this paper. Steven needs to perform encryption operations \(4n\) times and decryption operations \(4n\) times. Since the computation of multiplying by 0 or 1 is very fast, the time can be neglected. Using the NTRU cryptosystem, one encryption operation requires 1 modular multiplication operations, and one decryption operation requires 2 modular multiplication operations. Therefore, the Protocol 1 of this paper requires \(12n\) modular multiplication operations.

The computational complexity of Protocol 2: The NTRU cryptosystem is used in the Protocol 2 of this paper. Steven needs to perform encryption operations \(4n\) times and decryption operations 2 times. Tom needs to perform encryption operations \(4n\) times and decryption operations 2 times. Since the hash operations are very fast, the time required for these operations can be neglected. Therefore, Protocol 2 requires \(8n + 8\) modular multiplication operations.

Communication complexity

Measuring the communication complexity of a protocol is done through the number of communication rounds.

In26, both the Protocol 1 and Protocol 2 require two rounds of communication.

Protocols 3 and 4 in27 require three rounds of communication each.

Protocol 4 in28 requires two rounds of communication.

Protocol 5 and the MD protocol in29 each require six rounds of communication.

Communication complexity of Protocol 1: In the Protocol 1 of this paper, Steven and Tom need to engage in 2 rounds of communication.

Communication complexity of Protocol 2: In the Protocol 2 of this paper, due to the use of digital commitment method and the verification of computation results by decrypting ciphertexts separately and verifying each other's results to enhance security, Steven and Tom need to engage in 5 rounds of communication.

As shown in Table 1, both Protocol 1 and Protocol 2 in this paper have linear computational complexity, lower than Protocols 1 and 2 in26. Furthermore, Protocols 1 and 2 in this paper primarily involve modular multiplication, resulting in lower computational complexity compared to the modular exponentiation-based schemes in27,29,30,. In terms of communication complexity, Protocol 1 requires only two rounds of communication, fewer than the related protocols in27,30,. Protocol 2's communication rounds are fewer than those in29. Since Protocol 2 operates under the malicious model, its computational and communication complexities are slightly higher than those of Protocol 1. Overall, Protocols 1 and 2 exhibit low computational and communication complexities. Additionally, due to the use of the NTRU encryption algorithm, Protocols 1 and 2 can resist quantum attacks.

Experimental simulation

To further evaluate the efficiency of the protocols proposed in this paper, experimental simulations are conducted using Python language on the PyCharm platform, and comparisons are made with existing schemes.

Experimental environment: Windows 10 64-bit system, Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-8400 CPU @ 2.80 GHz, 16 GB RAM.

Experimental method: Randomly select two points \(S\), \(T\) and set the number of elements in the universal set \(U\) to \(n\). In the experiment, \(n\) is sequentially varied with different values \((n = 5,{ 7, } \cdots { ,23)}\), and for each \(n\), 1000 simulation experiments are conducted to calculate the average execution time of the protocols.

Experimental parameter settings: In the experiment, the encryption key lengths of Goldwasser-Micali, Paillier, and NTRU cryptosystems are set to 512 bits, and the length of the random number is set to 64 bits.

Figure 4 illustrates the execution time variation of Protocols 1 and 2 proposed in this paper, along with existing related schemes, as \(n\) increases.

As shown in Fig. 4, the execution time of Protocols 1 and 2 proposed in this paper increases linearly with the number of elements \(n\) in the universal set \(U\), with a relatively low growth rate. Compared to existing schemes, Protocol 1 has a shorter execution time for the same \(n\). Since Protocol 2 operates under the malicious model, its execution time is slightly higher than Protocol 1. Overall, Protocols 1 and 2 exhibit shorter execution times and better efficiency.

Subsequently, communication experiments were conducted to further evaluate the performance of the proposed schemes. Simulated experiments were performed on the Pycharm platform using Python (with a bandwidth of 100Mbps) to determine the potential latency of Protocols 1 and 2. In practice, latency between different networks varies, impacting protocol performance. This variability is not considered in the performance evaluation. The results of the communication experiments for Protocols 1 and 2, alongside existing schemes, are shown in Fig. 5.

The experimental results indicate that Protocols 1 and 2 have generally low latency, increasing linearly and slowly with the number of elements \(n\) in the universal set \(U\), demonstrating high communication efficiency. For a fixed \(n\), Protocol 1 exhibits lower latency than existing schemes, while Protocol 2, operating under the malicious model, shows slightly higher latency than Protocol 1 under the semi-honest model and related schemes.

Conclusion

Chebyshev distance is a vital distance metric. In archival management systems, computing Chebyshev distance without compromising the privacy of sensitive archival data enables similarity measurement, classification, and clustering, enhancing security in querying and sharing sensitive archives. This paper proposes a secure protocol for computing Chebyshev distance under a semi-honest model, based on the additive homomorphic properties of the NTRU cryptosystem and a vector encoding method. Additionally, a secure protocol for computing Chebyshev distance under a malicious model is proposed, ensuring fairness and effectively preventing attacks from malicious participants. The security of this protocol is demonstrated through the real/ideal model paradigm. Compared to existing solutions, the proposed protocol is more efficient and offers practical value.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

References

Wu, Y. et al. Generic server-aided secure multi-party computation in cloud computing. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 79, 103552 (2022).

Zhou, X., Xu, Z., Wang, C. et al. PPMLAC: high performance chipset architecture for secure multi-party computation. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture. 87–101 (2022).

Fang, V., Brown, L., Lin, W. et al. CostCO: An automatic cost modeling framework for secure multi-party computation. In 2022 IEEE 7th European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P). 140–153 (IEEE, 2022).

Yao, A.C. Protocols for secure computation. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Symposium on Foundation of Computer Science. 160–164. https://doi.org/10.1109/SFCS.1982.88 (IEEE, 1982).

Goldreich, O., Micali, S. & Wigderson, A. How to play any mental game. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. 218–229 (ACM, 1987).

Lindell, Y. & Pinkas, B. A proof of security of Yao’s protocol for two-party computation. J. Cryptol. 22(2), 161–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00145-008-9036-8 (2009).

Goldwasser, S., Ben-Or, M. & Wigderson, A. Completeness theorems for non-cryptographic fault-tolerant distributed computing. In Proceedings of the 20th STOC. 1–10 (1988).

Xia, F., Hao, R. et al. Adaptive GTS allocation in IEEE 802.15. 4 for real-time wireless sensor networks. J. Syst. Architect. 59(10), 1231–1242 (2013).

Shen, H. et al. An efficient aggregation scheme resisting on malicious data mining attacks for smart grid. Inf. Sci. 526, 289–300 (2020).

Kumar, P. et al. PPSF: A privacy-preserving and secure framework using blockchain-based machine-learning for IoT-driven smart cities. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 8(3), 2326–2341 (2021).

Fu, A., Zhang, X. et al. VFL: A verifiable federated learning with privacy-preserving for big data in industrial IoT. In IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics (2020).

Yao, Y. et al. Privacy-preserving max/min query in two-tiered wireless sensor networks. Comput. Math. Appl. 65(9), 1318–1325 (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. KNN-BLOCK DBSCAN: Fast clustering for large-scale data. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 51(6), 3939–3953 (2019).

Neelakandan, S. et al. Blockchain with deep learning-enabled secure healthcare data transmission and diagnostic model. Int. J. Model. Simul. Sci. Comput. 13(04), 2241006 (2022).

Fu, A. et al. VFL: A verifiable federated learning with privacy-preserving for big data in industrial IoT. IEEE Trans. Indus. Inform. 2020, 2513–2520 (2020).

Khan, N. A. et al. A secure communication protocol for unmanned aerial vehicles. CMC-Comput. Mater. Contin. 70(1), 601–618 (2022).

Liu, Y., Su, Z. & Wang, Y. Energy-efficient and physical layer secure computation offloading in blockchain-empowered Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. (2022).

Rosulek, M. & Trieu, N. Compact and malicious private set intersection for small sets. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 1166–1181 (2021).

Chase, M. & Miao, P. Private set intersection in the internet setting from lightweight oblivious PRF. Annual International Cryptology Conference 34–63 (Springer, 2020).

Chinnasamy, P. & Deepalakshmi, P. HCAC-EHR: Hybrid cryptographic access control for secure EHR retrieval in healthcare cloud. J. Ambient Intell. Hum. Comput. 2022, 1–19 (2022).

Zad, S., Heidari, M., Hajibabaee, P. et al. A survey of deep learning methods on semantic similarity and sentence modeling. In 2021 IEEE 12th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON). 0466–0472 (IEEE, 2021).

Shi, E. et al. Puncturable pseudorandom sets and private information retrieval with near-optimal online bandwidth and time. Annual International Cryptology Conference 641–669 (Springer, 2021).

Xiao, T. et al. Multi-keyword ranked search based on mapping set matching in cloud ciphertext storage system. Connect. Sci. 33(1), 95–112 (2021).

Poongodi, M. et al. 5G based blockchain network for authentic and ethical keyword search engine. IET Commun. 16(5), 442–448 (2022).

Ma, M. Y., Xu, Y. & Liu, Z. Privacy preserving Hamming distance computing problem of DNA sequences. J. Comput. Appl. 39(09), 2636–2640 (2019).

Fang, L. D., Li, S. D. & Dou, J. W. Secure manhattan distance computation. J. Cryptol. Res. 6(4), 512–525 (2019).

Dou, J. W., Ge, X. & Wang, Y. N. Secure Manhattan distance computation and its application. Chin. J. Comput. 43(02), 352–365 (2020).

Wu, H. F. & Song, Z. Z. Efficient and secure solution of Manhattan distance. Cybersp. Secur. 12(Z3), 49–55 (2021).

Xu, W. T. Research on three secure multi-party computation problems. Shaanxi Normal Univ. https://doi.org/10.27292/d.cnki.gsxfu.2021.002037 (2021).

Hoffstein, J., Pipher, J. & Silverman, J. H. NTRU: A ring-based public key cryptosystem. International Algorithmic Number Theory Symposium 267–288 (Springer, 1998).

Jia, Z. L., Zhao, X. L. & Li, S. D. Secure distributed multiset’s mode and multiplicity computation. J. Cryptol. Res. 10(1), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.13868/j.cnki.jcr.000582 (2023).

Shundong, L., Wang, W. & Runmeng, D. Protocol for Millionaires’ problem in malicious models. Sci. Sin. Inf. 51(1), 75 (2021).

Li, S.D. & Wang, D.S. Modern Cryptography: Theory, Method and Research Frontiers. 98–101; 132–145 (Science Press, 2009).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (72293583, 72293580), Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation (2021MS06006), 2023 Inner Mongolia Young Science and Technology Talents Support Project (NJYT23106), 2022 Basic Scientific Research Project of Direct Universities of Inner Mongolia (2022-101), 2022 Fund Project of Central Government Guiding Local Science and Technology Development (2022ZY0024), 2022 Chinese Academy of Sciences “Western Light” Talent Training Program “Western Young Scholars” Project (22040601), Open Foundation of State key Laboratory of Networking and Switching Technology (Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications) (SKLNST-2023-1-08), 2023 Inner Mongolia Archives Technology Project (2023-16), the 14th Five Year Plan of Education and Science of Inner Mongolia (NGJGH2021167), Inner Mongolia Science and Technology Major Project (2019ZD025), 2022 Inner Mongolia Postgraduate Education and Teaching Reform Project (JGSZ2022037), Inner Mongolia Postgraduate Scientific Research Innovation Project(S20231164Z), Research and Application Project of Big Data Privacy Security Computing System (2023); Tianjin Renai College & Tianjin University Teacher Joint Development Fund Cooperation Project (FZ231001); Baotou Rare Earth High tech Zone Enterprise Youth Science and Technology Innovation "1 + 1" Action Plan Project (202309); Yunnan Key Laboratory of Blockchain Application Technology (202305AG340008, YNB202301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. Design and implementation of the research, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft. W.C. Design and implementation of the research, Simulation, Writing-original draft. L.P. Conceptualization, Design of study, Acquisition of data, Investigation, Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. D.L. Conceptualization, Design of study, Acquisition of data, Investigation, Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. L.J. Design and implementation of the research, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft. G.X. Conceptualization, Design of study, Acquisition of data, Investigation, Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. X.C. Conceptualization, Design of study, Acquisition of data, Investigation, Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. X.L. Design and implementation of the research, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Chen, W., Peng, L. et al. Secure computation protocol of Chebyshev distance under the malicious model. Sci Rep 14, 17115 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67907-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67907-9