Abstract

The improvement of thermal exchange is of utmost interest in a wide range of engineering areas. The current study focuses on thermal evaluation involving natural radiation and convection in a fractionally arranged moving longitudinal fin model placed under a magnetic field. We implement the Levenberg Marquardt backpropagation (LMB) algorithm for investigating an innovative use of stochastic numerical computation for analyzing the efficiency of the temperature distribution in a porous moving longitudinal fin. The datasets for LMB have been created using a shooting approach for dynamic systems with varying ranges of different parameters. The validation, testing, and training processes are used to simulate networks using the LMB approach for diverse scenarios of moving porous fin models. The reliability of results is assessed based on the regression measures, absolute error, error histograms, mean square error, and other metrics for fuller numerical modeling of the suggested LMB to investigate the thermal efficiency and effectiveness of porous moving fin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In engineering execution, the concept of heat transfer has taken on a unique significance and many researchers and engineers are now interested in the configuration of heat exchange equipment that is crucial for emerging sectors. The phenomenon of heat transfer is incredibly useful in engineering and technological advancement. Initial applications of this technology include condensers in power plants and turbines that generate steam for tank engines. The use of heat exchangers in the petrochemical sectors and petroleum later came about because of a rapid growth of manufacturing operations and other methods of heat transfer included welding, electronic packaging, thermosyphons, casting, and geophysics. Radiation, conduction, and convection are the three fundamental forms of heat transport1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Every machine has an internal temperature threshold that it cannot exceed without shutting down. In a variety of electrical appliances, heat is dispersed via heat sinks and heat exchangers. It allows the equipment to operate at a lower temperature than its minimum operating temperature9. Extended surfaces called fins are widely used in electrical systems to speed up heat transfer. Numerous fin shapes, including rectangular, spherical, circular, and triangular, have recently been created. However, due to its straightforward construction methods, the longitudinal fin is the most efficient design10. Numerous studies have been reviewed in the literature to improve understanding of the thermal efficiency of fins and heat transfer rate. A porous substance with considerable thermal conductivity was employed to increase the thermal efficiency of various heat structures11. There are various fin varieties, but porous fin is the most useful and effective. The Darcy model was used for the very first time by Kiwen to develop fins made of a porous material12. Four distinct shapes—rectangular, convex, triangular, and exponential—are taken into consideration since it is expected that the width of circular fins changes with radius. By estimating a severe thermal transition in a porous fin and improving the efficiency of a porous fin, Kundu and Bhanja13 made significant improvements. Mordi evaluates the thermal conductivity of the porous, triangular-shaped fin concerning thermal conductivity that is temperature dependent14. For an equivalent mass of fins, a comparison between porous and solid fins has also been conducted. It was noted that, in an ideal condition, porous fins always transmit more heat than solid fins, making the choice of porous condition a beneficial design feature is presented. The thermal efficiency of convective radiative porous fins with rectangle profiles was the subject of a mathematical method proposed by Gorle and Bakier15. The thermal behavior of the convective radiative porous fin is studied by the least-squares approach, which provides several sectors and ceramic material possibilities16. According to a specific temperature requirement, Das and Ooi investigated how to forecast unknown and potential combinations of constituents in an inherently convective porous fin17. For this reason, the homotopy analysis technique (HAM) is used for validating the solutions. The outcomes of the Runge–Kutta technique are contrasted with the HAM for various instances. Examined are the consequences of several characteristics, such as convection and porosity.

Continuous moving fins have attracted a lot of attention because of their versatility and variety of applications. One of the developing study areas is the thermal behavior of continuously moving surfaces produced by extrusion, casting, hot tumbling, glass sheet, and powder metallurgy methods to produce both sheets and rods. While the material is being processed by a roller or furnace, heat is exchanged between the material and the surroundings. These metal shaping and processing techniques satisfy the fin approximation condition and may therefore be thermally described as continuously moving fins18. The insulated and convective tip of a moving fin with uniform speed were examined by Gireesha et al.19. Together with heat radiation and natural convection conditions, a numerical study of nanoscale implanted water-based hybrid nanoliquid flow across porous longitudinal fin moving at constant velocity is conducted. A porous medium can transport heat more quickly when it is moving than when it is stationary, according to research20. The distribution of temperatures along rectangular, straight, moving porous fin was discovered by using the homotopy perturbation technique to address the nonlinear energy issue21 and to comprehend the significance of each significant parameter in the heat transmission through porous fins, their roles have been explored. Additionally, a comparison of porous and solid fins has been provided, and the findings show that a greater rate of heat transfer may be attained by choosing a suitable value for porosity. The finite element approach was used to study the wet-moving porous fin of radial shape moving at constant speed22. A moving rectangular porous fin’s effectiveness and temperature distribution variations were evaluated using the Darcey model23 and examining the heat transfer phenomena in fin saturated in aquatic carbon nanotubes, such as single-walled and multiwalled carbon nanotubes, is the goal of this work. The analysis in the suggested paper uses the Darcy’s model. Gamaoun et al. examined the non-Fourier temperature dispersion in a moving fin with a longitudinal profile convective radiative. Using the Cattaneo-Vernotte thermal model, dovetail fin heat conduction behavioral patterns were assessed24. To analyze the heat transfer analyses of a moving, porous fin with a longitudinal profile under a magnetic field, Pavithra et al., use the ADSTM25. The findings demonstrate that the heat load, component volume fraction, and porosity volume fraction all have an impact on natural frequency distributions. Furthermore, there are little discrepancies between the natural frequencies derived from the LTR and the NLTR. The discussion of an investigation Heat transfer factor, thermal emissivity, and thermal conductivity are changing on longitudinal and exponentially moving fins26. An experiment was conducted on a moving porous convective fin influenced by temperature surface emissivity, heat transfer factor, and thermal conductivity27. It is evident from a survey of the literature that a range of analytical and numerical techniques have been utilized to conduct thermal assessments on moving porous fins with a diversity of physical and geometrical features.

However, supervised learning oriented machine approaches have not been applied to the proposed fin problem. To arrive at approximations for a range of technological challenges, the researcher has extensively used a computer solver based on artificial intelligence. Ahmad studied the heat impact on a rectangular profile fin with internal heat generation using artificial neural networks (ANNs) that were optimized using an interior-point method (GA-IPT) and genetic algorithms in various scenarios28. There are numerous possible uses, with the stated research being extremely important in fields like the gas cloud system29, fuel ignition30,31, dusty plasma model32, Reynold and eye models33,34,35, MHD nanofluid36, hunter saxton model37, human dermal region models38,39,40, hybrid nanofluid model41,42, nanofluidic models43,44,45,46 Thomas–Fermi fin dynamical model47, forecasting of financial markets48, Lane–Emden models49 nonlinear multiple singularity problem50. It is used in this instance to maximize the thermal performance of a moving porous longitudinal fin. The mentioned literature motivates the authors to study the moving porous fin model to examine the temperature distribution under the effect of a magnetic field via a novel Stochastic Computational Levenberg Marquardt backpropagation-based technique moreover, this technique is not yet applied to the proposed model of fin, here below we present the designed study’s significant contributions.

-

Using the moving fin model’s reference solution and the numerical approach referred to as the shooting technique, the mean square inaccuracy index is applied to the merit function to assess the computational outcomes of moving fin models.

-

Using an entirely novel intelligence computing methodology, the effectiveness is investigated for the longitudinal moving porous.

-

To obtain the decision variables for NNs to obtain the desired solution of the proposed model, the validation, training, and testing process is carried out using LMB.

-

Through statistical analysis including fitness plot curves, error analysis, auto-correlation, histogram error, and regression, the accuracy, efficiency, validation, and convergence of the provided scheme are investigated.

The study’s additional sections are arranged as follows: The formulation of the problem for the moving longitudinal porous fin model is described in “Problem formulation” section. Results and analysis are presented in “Results and discussion” section, followed by the conclusion in “Conclusion” section.

Problem formulation

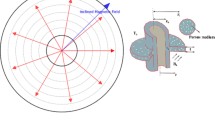

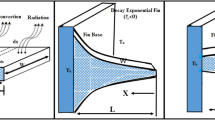

The Fig. 1 depicts area.\(A_{1}\), width \(w_{1}\), length L, and thickness \(\tilde{t}\) of a porous longitudinal profile attached to a primary surface and moving horizontally with uniform velocity v. This fin is intended to increase cooling.

The Darcy model is used to explain how air swirls around a porous fin and enters the pores. The ambient temperature \(T_{\infty }\) is considered and the fin’s base is maintained at a constant temperature \({T}_{B}\). An even magnetic-field is given in y direction. Below is a list of some of the suppositions that were utilized to make the model simpler. Inside of the porous media, which has a single base fluid and is homogenous and isotropic, the solid and fluid surfaces are in thermal equilibrium. Fin temperature only varies in the x direction, fluctuations in the other directions are insignificant and are therefore ignored. The energy balance model equation for the porous fin is presented by Ref.50.

Natural convection produces a change in the fluid’s mass flow rate as it passes through a porous medium, which is represented by.

We have the following from the Darcy model:

where the thermal expansion coefficient, fluid density, and kinematic viscosity are represented by \(\alpha\), \(\rho\) and \(v_{i}\), respectively. Fourier’s law of conduction provides us with,

It would be feasible to use51, in place of the phrase \(\frac{{J_{c}^{ * } \times J_{c}^{ * } }}{\sigma }\)

where current conductivity intensity, magnetic field strength, electrical conductivity, and the axial velocity are represented by \(J_{c}^{ * }\), \(B_{{^{i} }}\), \(\sigma\), \(\varsigma\) respectively. A slight temperature difference develops within the material during the heat flow. Consequently, in this case, the \(T^{*4}\) the term is reduced to a temperature (linear function)51

Equations (2) to (5) are substituted into Eq. (1) to yield,

The dimensionless parameters are now introduced as,

Applying Eq. (7) to Eq. (6) results in

Since the fin tip surface area often constitutes a small portion of the total fin area or the fin’s tip is made of an insulating material, it is assumed that heat transmission from the fin tip is negligible in this case. Consequently, the relevant boundary conditions are provided by.

Afterward, non-dimensionalizing yield with adiabatic boundary conditions.

where

are Peclet number, radiation parameter, Hartman number, thermo-geometric parameter, and porosity parameter respectively.

Heat-transfer rate

The heat transmission rate at the fin’s base is expressed as

The fin’s dimensionless rate of heat transmission is defined via.

Numerical analysis

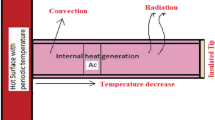

The Computational Levenberg Marquardt backpropagation-based technique is designed to solve the moving pours fin to examine the temperature distribution. The data set is obtained through the Shooting method via Mathematica software then the obtained data set is trained through the Levenberg Marquardt backpropagation considering a total of 70% of data is utilized for training, 15% for testing, and 15% for validation. The data set is trained with different optim settings for the best known (weights) that provide the close solution which means the mean square error based on the Jacobian matrix goes to zero. The proposed Levenberg Marquardt backpropagation used the backpropagation procedure for training the data and it works on the basis of Gradient decent and Guas Newton methods by considering different situations depending on the far and close solution. Every phase of the current solver’s working method is provided in graphical form shown in Fig. 2 together with the essential problem description.

Results and discussion

The nonlinear ordinary differential equation (ODE) shown in Eq. (9) provides a representation of the moving longitudinal porous fin model. The shooting technique and the built-in MATLAB toolbox are used to solve Eq. (9) using LMB. Several examples are developed for every possible scenario, Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 and 24 corresponding to the proposed LMB describe the graphical and numerical solutions regarding the fin’s length as well as temperature. Table 1 includes an explanation of the scenarios as well as various cases for computing \(\phi\)(S). By varying Si = 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 and keeping all other parameters constant, scenario 1 with 3 cases is built to examine the behavior.

Like scenario 1, the cases in scenarios 2, 3, 4, and 5 are built by variations in M, Nr, Pe, and H, respectively. Figures 3 and 4 show the graphical results of each scenario. The moving fin model is represented by a nonlinear ordinary differential equation. The data set for each scenario is formed using the shooting method and the NDSolve tool in Mathematica. The numerical results of \(\phi\) (S), which were generated using the LMB solver, are displayed in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12. The distribution of temperature of the moving fin is numerically examined in this section under the impact of numerous other parameters. The temperature drops as the Peclet number, convection radiation parameter, thermogeometric parameter, Hartman, and porosity parameters are raised. The temperature transmission of the moving fin is numerically examined here, under the impact of numerous other parameters.

With the use of LMB, the staging of a porous moving, longitudinally profiled fin subjected to radiation and convection under the influence of a continuous magnetic field has been investigated. By varying every parameter separately, it is possible to analyze how different parameters affect the thermal distribution of moving porous fins. The fin’s surface temperature decreases as the porosity parameter (Si) increases. This is because Si has both a high Rayleigh number and a Darcy number, thus when Rayleigh increases, the fin’s permeability also rises, increasing the amount of fluid that may travel through the fin’s pores. As the radiation parameter increases, the temperature distribution in the fin decreases. Because of the radiation effect being enhanced by an increase in the radiation parameter, additional heat is transferred from the fin surface.

As a result, the fin’s temperature drops, and it cools. The fin’s temperature increases as the Hartman parameter rises. When the value of the Peclet number is increased by small fractions, the rise in temperature of fin tips is negligibly small, however, a sudden decrease is observed at 0.5. The rising thermogeometric parameter causes increased convection from the fin’s surface. As a result of the increased heat transfer rate from its surface, the temperature of the fin reduces. The absolute value indicates the difference in between a numerical and exact value. Figures 3a,c,e, 4a,c display the absolute error (AEs) for each scenario. For each of these circumstances, the range of AEs is as follows: \({10}^{-08}\) to \({10}^{-04}\), \({10}^{-07}\) to \({10}^{-03}\), \({10}^{-07}\) to \({10}^{-04}\), \({10}^{-08}\) to \({10}^{-04}\) and \({10}^{-07}\) to \({10}^{-04}\). Figures 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 and 24 provide graphical illustrations of the statistical analysis and performance of LMB algorithms.

Figures 5, 9, 13, 17 and 21 offer a graphical illustration of the training state and performance. Performance is measured in terms of MSR, which distinguishes between observation and simulation. The network contains both the intended output and input, and the graph is generated using the MSR and epoch. After supplying input to the system, the target and output are compared. The higher the performance, the lower the mean square value. The best performance of \({10}^{-10}\), \({10}^{-10}\), \({10}^{-13}\) for epochs 45, 111, and 48 of scenario 1 are shown in Fig. 5a,c,e, respectively. Compared to the other cases in scenario 1, case 3 performs better. The performance of scenarios 2 and 3 is shown in Figs. 9a,c,e and 13a,c,e.

Scenario 2 Case 3 and Scenario 3 case 1 have performance values of \({10}^{-11}\) for both, against 53 and 16 epochs, respectively, and are the highest validation performance instances among them. Figures 17a,c,e and 21a,c,e display the results of scenarios 4 and 5. Among these, scenario 4 Case 3 and scenario 5 Case 1 rank highest in terms of validation performance instances, which have performance values of \({10}^{-10}\), \({10}^{-12}\) against 21 and 16 epochs. The network contains both the intended output and input, and the graph is created using MSE and epoch.

After transporting input to the system, the target and output are contrasted. Performance plots show that the training, validation, and testing trajectories are consistent and converging at a certain point on the best line, indicating optimal system performance. Subcaptions b, d, and f of Figs. 9, 5, 13, 17, and 21 show the training state while simultaneously showing the convergence rate.

These graphs demonstrate how the recommended LMBP-ANNs solver converges rapidly by illustrating how the coefficients of Mu and gradient drop as the value of epoch rises. The neural network training procedure uses the Mu as a control parameter. The values for testing, validation, training as well as Mu of all scenarios with cases, are described in Table 2. Figures 6, 10, 14, 18 and 21’s subfigures a, c, and e depict a graphic illustration of the error histogram.

The histogram, which displays the discrepancy between target and predicted values during feed-forward NN training, serves as an example of the method’s accuracy. Each histogram graph is made up of 20 vertical bars, or “bins”. The zero-error line, depicted as a vertical red line, indicates that the date’s negative and positive sections are evenly distributed. The graph’s bars show how frequently data is utilized for validation, training, and testing, and histogram analysis reveals the training process uses a large amount of data. Figure 6 depicts a histogram analysis of the first scenario and all 3 cases, with the instances against zero error being 6.93 × \({10}^{-8}\), 7.58 × \({10}^{-7}\) and 5.81 × \({10}^{-8}\) with 40, 38, and 50 instances, indicating that case 3 is preferable to the others. The finest representations of S2 and S3 are shown in Figs. 10 and 14. Case 1 of S2 and Case 3 of S3 with 30 and 130 instances, respectively show the best histogram analysis, against a zero error line of 1.36 × \({10}^{-6}\) and − 2.2 × \({10}^{-7}\). Figures 18, and 22 depict the best outcomes for S4 and S5, including S4 with case 3, S5 with case 1 with instances 115, and 100 against a zero error of 8.78 × \({10}^{-9}\) and − 1.4 × \({10}^{-7}\).

The subfigures of Figs. 6, 10, 14, 18 and 21 are graphical illustrations of the auto-correlation of each scenario with cases, where Fig. 6b,d,f depicts auto-correlation of the error of S1, and subfigures (b), (d), (f) of 10, 14, 18 and 21 depicts the autocorrelations of S 2–5 with every case. The graphical illustration of the regression analysis is shown in subfigures (a), (c) of Figs. 7, 11, 15, 19 and 23 also subfigures (a) of Figs. 8, 12, 16, 18 and 24. Figures 7 and 8 provide a regression analysis of the first scenario for every instance at epochs 45, 111, and 48.

Tables 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 present the error analysis of all Si, M Nr, Pe, H and for all cases of scenarios 1 to 5 for longitudinal moving porous fin. These tables describe the proposed solver’s accuracy, which is 4 to 6, 4 to 6, 3 to 6, 4 to 6, and 3 to 8 decimal places. Figures 12 and 13 show the most efficient analysis of regression for scenarios 2,3, 4, and 5 for epochs 58, 105, 62, and 22, respectively. The result of the regression function graphically depicts the connection between the output and the target values. The connection between the goals and the outcomes is perfectly linear if R = 134. The optimum fit can be seen when the lines are straight. The output is equal to the target as indicated by the dotted lines. The ideal fit is shown in regression plots by the condition Y = T. The training, validation, testing, and R values steps are utilized to ascertain the best possible fit for the model.

Figures 7, 12, 19 (subfigures b and d) and 8, 13, and 20 (subfigure e) show the fitness graph of validation, testing, validation, and training for every case of scenarios 1–5. The plot of fitness demonstrates the target and output relationship of the dataset. If the targets and output overlap, the findings provide an accurate solution.

The fitness graph illustrates that the system has been properly trained because the targets and output for testing, validation, and training are overlapping. Figures 7b,d and 8b show the fitness graph for every case of S1, with error at the unit time being \({10}^{-5}\) in C1, C2, and \({10}^{-6}\) in C3.

In the work that is being presented, Min, Max, Standard deviation (std), and the mean measures are used to find the link between the data sets that were generated and the trained neural network responses to the moving porous fin that is suggested using LMBP and has a longitudinal profile.

Additionally, as shown in the following Table 13, all approximated minimum values for Min, Max, Standard deviation, and mean confirm the best performance, convergence, effectiveness, and precision of the used computational methods.

Conclusion

A longitudinal porous moving fin underwent a thorough thermal examination for better cooling of electrical equipment. The generated model of the fin LMB solver is graphically and numerically solved using a computing program. The porosity parameter, thermogeometric, Peclet number, and Hartman number are found to have a significant impact on the rate of heat transfer. The following results have been noticed.

-

For longitudinal moving porous fin, it is found that when the value of the Peclet number is increased by small fractions, the rise in temperature of fin tips is negligibly small, however, a sudden decrease is observed at 0.5. On the contrary, when the value of the Hartman parameter goes on rising, the temperature of the fin tip also rises. Moreover, the fin’s surface temperature decreases as the porosity parameter (Si) increases.

-

It has been noted that the system’s performance is more consistent when the MSE value drops. In comparison to the other cases of remaining scenarios, Case 3 of Scenario 1 for longitudinal moving porous fin has the best validation performance of 5.5523 × \({10}^{-13}\) with an epoch of 49.

-

The histogram illustrates how much the employed technique has reliability. The case with the better histogram for longitudinal profile, out of all the cases, is Case 3 of Scenario 4, with 8.78 × \({10}^{-09}\) Along 120 instances.

-

The estimated accuracy of the system is shown by the absolute errors (AEs). Comparing scenario 4 case 2 to other scenarios and their cases, they have much better absolute errors ranging from \({10}^{-09}\) to \({10}^{-04}\).

-

The Mu and gradient values indicate a faster convergence rate. Auto-correlation can be used to develop the link between two variables. An inverse relationship is shown by an inverse correlation, whereas a direct link is indicated by a positive correlation.

-

Regression is used to investigate the linear relationship between target and output.

-

The fitness graph demonstrates that data is adequately trained and provides accurate results for the problem.

In the future the designed method can be applied to investigate the behavior/dynamical effect of changing involved parameters of real-world problems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- T*:

-

Local fin temperature

- Si:

-

Porosity parameter

- \(C_{p}\) :

-

Specific heat under constant pressure

- Nr :

-

Conduction-radiation parameter

- g:

-

Gravity-induced acceleration

- S:

-

Axial coordinate with no dimensions

- \(h\) :

-

Coefficient of heat transmission

- \(k_{eff}\) :

-

Ratio for effective thermal conductivity

- H:

-

Hartman number

- \(M\) :

-

Dimensionless thermo-geometric factor

- \(w_{1}\) :

-

The fin’s width

- \(k^{*}\) :

-

Permeability

- \(Ra\) :

-

Rayleigh number

- \(q\) :

-

Rate of heat transfer

- \(\zeta\) :

-

Axial velocity

- \(B_{i}\) :

-

Magnetic field strength

- \(\rho\) :

-

Fin perimeter

- \(L\) :

-

Fin’s length

- \(T_{B}\) :

-

Fin’s base temperature

- \(Da\) :

-

Darcy number

- \(v_{w}\) :

-

The fluid velocity traveling through the fin at all points

- h:

-

Coefficient of heat transfer

- m*:

-

The rate of mass flow of fluid traveling through a porous fin

- V:

-

Fin’s velocity

- \(J_{c}^{ * }\) :

-

Intensity of conduction current

- \(\beta\) :

-

The thermal expansion coefficient of the surrounding fluid

- \(\sigma\) :

-

Electrical conductivity

- \(\tilde{\sigma }\) :

-

Stefan-Boltzmann constant

- \(v_{i}\) :

-

Ambient fluid’s kinetic viscosity

- \(\rho_{f}\) :

-

Ambient fluid density

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

Emissivity

- \(\theta\) :

-

Porosity

- \(\phi\) :

-

Temperature (dimensionless)

- ANNs:

-

Artificial neural networks

- ODE:

-

Ordinary differential equations

- LMB:

-

Levenberg–Marquardt back-propagation

- L :

-

Fin’s length

- B:

-

Fine base

- NN:

-

Neural network

- ADSTM:

-

Adomian decomposition smudu transformation method

- GAIPT:

-

Genetic algorithm interior point technique

References

Gurrum, S. P., Suman, S. K., Joshi, Y. K. & Fedorov, A. G. Thermal issues in next-generation integrated circuits. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 4(4), 709–714 (2004).

Jamshed, W. et al. Implementing renewable solar energy in presence of Maxwell nanofluid in parabolic trough solar collector: A computational study. In Waves in Random and Complex Media 1–32 (2021).

Oguntala, G. A., Sobamowo, G. M., Abd-Alhameed, R. A. & Noras, J. M. Numerical study of performance of porous fin heat sink of functionally graded material for improved thermal management of consumer electronics. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 9(7), 1271–1283 (2019).

McGlen, R. J., Jachuck, R. & Lin, S. Integrated thermal management techniques for high power electronic devices. Appl. Therm. Eng. 24(8–9), 1143–1156 (2004).

Kraus, A. D., Aziz, A., Welty, J. & Sekulic, D. P. Extended surface heat transfer. Appl. Mech. Rev. 54(5), B92 (2001).

Wang, Y. & Vafai, K. An experimental investigation of the thermal performance of an asymmetrical flat plate heat pipe. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 43(15), 2657–2668 (2000).

Kiwan, S. & Al-Nimr, M. A. Using porous fins for heat transfer enhancement. J. Heat Transf. 123(4), 790–795 (2001).

Alkam, M. K. & Al-Nimr, M. A. Solar collectors with tubes partially filled with porous substrates. J. Solar Energy Eng. 121, 20 (1999).

Abu-Hijleh, A. K. Enhanced forced convection heat transfer from a cylinder using permeable fins. J. Heat Transf. 125(5), 804–811 (2003).

Gorla, R. S. R. & Bakier, A. Y. Thermal analysis of natural convection and radiation in porous fins. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 38(5), 638–645 (2011).

Bhanja, D., Kundu, B. & Aziz, A. Enhancement of heat transfer from a continuously moving porous fin exposed in convective–radiative environment. Energy Convers. Manag. 88, 842–853 (2014).

Hatami, M. & Ganji, D. D. Thermal performance of circular convective–radiative porous fins with different section shapes and materials. Energy Convers. Manag. 76, 185–193 (2013).

Moradi, A., Hayat, T. & Alsaedi, A. Convection-radiation thermal analysis of triangular porous fins with temperature-dependent thermal conductivity by DTM. Energy Convers. Manag. 77, 70–77 (2014).

Kundu, B. & Lee, K. S. A proper analytical analysis of annular step porous fins for determining maximum heat transfer. Energy Convers. Manag. 110, 469–480 (2016).

Ahmad, I., Zahid, H., Ahmad, F., Raja, M. A. Z. & Baleanu, D. Design of computational intelligent procedure for thermal analysis of porous fin model. Chin. J. Phys. 59, 641–655 (2019).

Baslem, A. et al. Analysis of thermal behavior of a porous fin fully wetted with nanofluids: Convection and radiation. J. Mol. Liq. 307, 112920 (2020).

Hoseinzadeh, S., Moafi, A., Shirkhani, A. & Chamkha, A. J. Numerical validation heat transfer of rectangular cross-section porous fins. J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 33(3), 698–704 (2019).

Hoseinzadeh, S., Heyns, P. S., Chamkha, A. J. & Shirkhani, A. Thermal analysis of porous fins enclosure with the comparison of analytical and numerical methods. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 138(1), 727–735 (2019).

Gireesha, B. J., Sowmya, G., Khan, M. I. & Öztop, H. F. Flow of hybrid nanofluid across a permeable longitudinal moving fin along with thermal radiation and natural convection. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 185, 105166 (2020).

Khatami, S. & Rahbar, N. An analytical study of entropy generation in rectangular natural convective porous fins. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 11, 142–149 (2019).

Deshamukhya, T., Hazarika, S. A., Bhanja, D. & Nath, S. An optimization study to investigate non-linearity in thermal behaviour of porous fin having temperature dependent internal heat generation with and without tip loss. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 67, 351–365 (2019).

Gireesha, B. J., Sowmya, G. & Gorla, R. S. R. Nanoparticle shape effect on the thermal behaviour of moving longitudinal porous fin. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. N J. Nanomater. Nanoeng. Nanosyst. 234(3–4), 115–121 (2020).

Sowmya, G., Gireesha, B. J. & Sindhu, S. Thermal exploration of radial porous fin fully wetted with SWCNTs and MWCNTs along with temperature-dependent internal heat generation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 234(24), 4945–4952 (2020).

Wang, Y. Q. & Zu, J. W. Vibration behaviors of functionally graded rectangular plates with porosities and moving in thermal environment. Aerospace Sci. Technol. 69, 550–562 (2017).

Wang, Y. Q. Electro-mechanical vibration analysis of functionally graded piezoelectric porous plates in the translation state. Acta Astron. 143, 263–271 (2018).

Wang, Y., Ye, C. & Zu, J. W. Identifying the temperature effect on the vibrations of functionally graded cylindrical shells with porosities. Appl. Math. Mech. 39(11), 1587–1604 (2018).

Wang, Y. Q., Ye, C. & Zu, J. W. Vibration analysis of circular cylindrical shells made of metal foams under various boundary conditions. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 15(2), 333–344 (2019).

Ye, C. & Wang, Y. Q. Nonlinear forced vibration of functionally graded graphene platelet-reinforced metal foam cylindrical shells: Internal resonances. Nonlinear Dyn. 104(3), 2051–2069 (2021).

Wang, Y. Q., Ye, C. & Zu, J. W. Nonlinear vibration of metal foam cylindrical shells reinforced with graphene platelets. Aerospace Sci. Technol. 85, 359–370 (2019).

Teng, M. W. & Wang, Y. Q. Nonlinear forced vibration of simply supported functionally graded porous nanocomposite thin plates reinforced with graphene platelets. Thin-Walled Struct. 164, 107799 (2021).

Yang, F. L. & Wang, Y. Q. Free and forced vibration of beams reinforced by 3 D graphene foam. Int. J. Appl. Mech. 12(05), 2050056 (2020).

Masood, Z., Majeed, K., Samar, R. & Raja, M. A. Z. Design of Mexican hat wavelet neural networks for solving Bratu type nonlinear systems. Neurocomputing 221, 1–14 (2017).

Hussain, S. I., Ahmad, I. & Yasmeen, N. The remarkable role of hydrogen in conductors with copper and silver nanoparticles by mixed convection using viscosity Reynold’s model. In International Conference on Nonlinear Dynamics and Applications 49–60 (Springer, 2023).

Raja, M. A. Z., Shah, F. H. & Syam, M. I. Intelligent computing approach to solve the nonlinear Van der Pol system for heartbeat model. Neural Comput. Appl. 30(12), 3651–3675 (2018).

Ilyas, H., Ahmad, I., Hussain, S. I., Shoaib, M. & Raja, M. A. Z. Design of evolutionary computational intelligent solver for nonlinear corneal shape model by Mexican Hat and Gaussian wavelet neural networks. In Waves in Random and Complex Media 1–23 (2024).

Butt, Z. I. et al. Radial basis kernel harmony in neural networks for the analysis of MHD Williamson nanofluid flow with thermal radiation and chemical reaction: An evolutionary approach. Alexand. Eng. J. 103, 98–120 (2024).

Ahmad, I. et al. Numerical computing approach for solving Hunter–Saxton equation arising in liquid crystal model through sinc collocation method. Heliyon 7, 7 (2021).

Ahmad, I. et al. Optimal control of thermoregulation in the human dermal regions investigated through the stochastic integrated techniques. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 58, 104381 (2024).

Ahmad, I. et al. Integrated stochastic investigation of singularly perturbed delay differential equations for the neuronal variability model. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2023(1), 1918409 (2023).

Ahmad, I., Ilyas, H., Hussain, S. I. & Raja, M. A. Z. Evolutionary techniques for the solution of bio-heat equation arising in human dermal region model. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 49(3), 3109–3134 (2024).

Hussain, S. I., Ahmad, I., Raja, M. A. Z. & Umer, C. M. Z. A computational convection analysis of SiO2/water and MoS2-SiO2/water based fluidic system in inverted cone. Eng. Rep. 5(11), e12660 (2023).

Ahmad, I. et al. On the dynamical behavior of nonlinear Fitzhugh-Nagumo and Bateman-Burger equations in quantum model using Sinc collocation scheme. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136(11), 1108 (2021).

Ahmad, I., Hussain, S. I., Usman, M. & Ilyas, H. On the solution of Zabolotskaya–Khokhlov and diffusion of oxygen equations using a sinc collocation method. Part. Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 4, 100066 (2021).

Butt, Z. I. et al. Neuro-heuristic computational intelligence approach for optimization of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic influence on a nano viscous fluid flow. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2023(1), 7626478 (2023).

Ahmad, I., Hussain, S. I., Raja, M. A. Z. & Shoaib, M. Transportation of hybrid MoS2–SiO2/EG nanofluidic system toward radially stretched surface. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48(1), 953–966 (2023).

Butt, Z. I. et al. Intelligent computing paradigm for unsteady magneto nano-polymeric Casson nanofluid with Ohmic dissipation and thermal radiation. Chin. J. Phys. 88, 212–269 (2024).

Ahmad, I., Qureshi, H., Raja, M. A. Z., Hussain, S. I. & Fatima, S. A novel design of stochastic approximation treatment of longitudinal rectangular fin dynamical model. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 54, 104042 (2024).

Butt, Z. I. et al. Inverse multiquadric kernel-based neuro heuristic approach to analyze the unsteady MHD nanofluid flow via permeable elongating surface. ZAMM J. Appl. Math. Mech. 104(2), e202300390 (2024).

Ahmad, I., Raja, M. A. Z., Bilal, M. & Ashraf, F. Neural network methods to solve the Lane-Emden type equations arising in thermodynamic studies of the spherical gas cloud model. Neural Comput. Appl. 28(1), 929–944 (2017).

Ahmad, I., Ibrar Hussain, S., Ilyas, H., Jabeen, S. & Iqrar, A. On the applications of collocation method for numerically analyzing the nonlinear Degasperis-Procesi and Benjamin–Bona–Mahony equations. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 38(20), 2450264 (2024).

Pavithra, C. G., Gireesha, B. J. & Keerthi, M. L. Heat transfer analysis of a convective radiative porous moving longitudinal fin exposed to magnetic field by Adomian decomposition sumudu transform method. Phys. Scr. 98(4), 045208 (2023).

Ahmad, I. et al. Intelligent computing to solve fifth-order boundary value problem arising in induction motor models. Neural Comput. Appl. 29(7), 449–466 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The idea and design of the study, the methodology, the analysis and interpretation of findings, and the writing and composition of the article is completed equally by I. Ahmad, MAZ. Raja, S.I. Hussain, H. Ilyas, and Z. Mohayyuddin.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, I., Raja, M.A.Z., Hussain, S.I. et al. Design of stochastic computational Levenberg Marquardt backpropagation-based technique to investigate temperature distribution of longitudinal moving porous fin. Sci Rep 14, 17359 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67959-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67959-x