Abstract

Rock typing techniques have relied on either electrical or hydraulic properties. The study introduces a novel approach for reservoir rock typing, the hydraulic-electric index (HEI), which combines the strengths of traditional electrical and hydraulic rock typing methods to characterize carbonate reservoirs more accurately. By normalizing the ratio of permeability and formation resistivity factor (K/FRF) with respect to porosity, the HEI method is applied to two datasets of carbonate core samples: dataset 1 consists of 112 carbonate core samples from the Tensleep formation in the Bighorn basin of Wyoming and Montana, and dataset 2 includes 81 carbonate core samples from the Asmari formation in the south-west of Iran. Statistical analysis confirms the effectiveness of the HEI in predicting permeability, with high determination coefficients for both datasets (resulting in determination coefficients (R2) of 0.965 and 0.904 for dataset 1 and dataset 2, respectively). The results classify the rock samples into distinct rock types, nine rock types for dataset 1 and four rock types for dataset 2, and demonstrate the HEI ability to capture the relationship between hydraulic conductivity and electrical resistivity in carbonate reservoir rocks. Applying the HEI method to the validation dataset yielded highly accurate permeability predictions, with average of determination coefficients of 0.883 and 0.859 for dataset 1 and dataset 2, respectively. Validation of the HEI method further confirms (20% of the dataset was set aside for validation, while the remaining 80% was used for the rock typing approach (5 folds)) its accuracy in predicting permeability, highlighting its robust predictive capacity for estimating permeability in carbonate reservoirs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reservoir characterization is a critical endeavour in the geo-energy industry, playing an essential role in the efficient recovery of hydrocarbons and the optimization of reservoir management strategies1,2,3,4,5. Understanding the complex interplay between various rock properties is essential for predicting fluid flow behaviour and making informed decisions in exploration and production activities6,7,8,9. Carbonate reservoirs, in particular, suffer from unique challenges due to their complex pore systems and diagenetic alterations. As a result of these complexities, it is difficult to establish a general mathematical model or strategy that accurately predicts the critical petrophysical properties in carbonate reservoirs10,11,12,13,14. In addition, the conventional rock typing approaches may not fully capture the intricate nature of the carbonate rocks15,16,17.

The significance of electrical rock typing lies in its ability to capture the electrical response of rocks, which is influenced by pore geometry, fluid saturation, mineralogy, and the presence of conductive minerals18,19,20,21. Electrical rock typing is a method of describing rocks in reservoirs based on their electrical properties. It involves the measurement of various electrical parameters, such as resistivity and classification of rocks into different electrical flow units (EFU)22,23. Electrical properties offer valuable insights into fluid distribution, connectivity, and flow behaviour within the subsurface. Otherwise, hydraulic rock typing focuses on permeability and porosity, which are influenced by factors like grain size, sorting, cementation, and diagenesis24,25,26. Understanding hydraulic rock types helps to predict fluid flow paths, identify flow barriers, and optimize reservoir development strategies27,28,29. These factors can vary significantly within a reservoir, leading to a complex relationship between permeability and porosity. Similarly, the FRF, which measures how easily electric currents can flow through a porous medium, is also affected by the complex pore structure of carbonate rocks30. The presence of different types of pores and their connectivity can significantly impact the FRF. In recent years, substantial advancements have been made in rock typing methodologies, driven by integrating advanced petrophysical measurements, data-driven analysis techniques, and machine-learning algorithms. These innovations have improved the accuracy and efficiency of rock typing, enabling more informed decision-making in oil and gas exploration and production31,32,33,34.

The geometry of pores and interconnections between them significantly influences carbonate rock's electrical and hydraulic properties. This is especially noticeable for carbonate rock35,36,37,38. However, the relationship between permeability and FRF is not straightforward in carbonate reservoirs39,40,41. This is because carbonate rocks are highly heterogeneous and contain various pore types, including intergranular, vuggy, and fracture porosity. Engineers and geoscientists often rely on empirical correlations and statistical analysis to overcome this challenge and estimate permeability from FRF measurements in carbonate reservoirs. These correlations are derived from well data and are specific to certain reservoir conditions or regions. Traditionally, rock typing techniques have relied solely on electrical properties, such as resistivity and conductivity, or hydraulic properties, such as permeability and porosity42,43.

The classification of subsurface rocks is done through the use of electrical properties in electrical rock typing. It helps to bridge the gap between geophysical measurements and geological interpretation30. The cementation factor, often denoted by the symbol "m", is a parameter used in petrophysics to describe the cementation level or degree of bonding between mineral grains in a rock formation. It is part of Archie’s equation, which relates the formation resistivity factor of a rock to its porosity. A higher cementation factor indicates stronger bonding between grains, leading to lower porosity and increased electrical resistivity44,45,46,47. Tortuosity refers to the complexity or irregularity of the flow path within a porous medium, such as a rock. In petrophysics, the tortuosity factor ("a") measures how convoluted or twisted the flow path is for fluids and electrical currents within the rock. It is a critical parameter in models describing permeability and electrical conductivity in porous media. Higher tortuosity values indicate more intricate pathways, which can affect the transport of fluid and electrical current through the rock matrix48,49,50. The FRF is a term used in petrophysics and reservoir engineering to describe the relationship between the resistivity of a rock formation and the resistivity of the fluids within it, typically the formation water. The FRF can be defined as follows (Eq. 1):

where FRF represents the ratio of the resistivity of the rock saturated with brine (Ro) to the resistivity of the formation water (Rw). Archie introduced a linear relationship, represented on a log–log scale, between FRF and porosity (\(\upphi\)). The Eq. (2) explains the relationship between FRF and \(\upphi\)44:

Rezaee et al.51 conducted an extensive investigation involving 92 clean carbonate rock samples, with the primary objective of exploring the FRF. To better understand the associated tortuosity and cementation factors, they classified the rock samples into distinct groups based on criteria such as permeability, petro-facies, and reservoir rock types. Their research led them to a notable conclusion: relying solely on the classification of rock samples using these criteria was insufficient for accurately predicting the values of "a" and "m". In response to this challenge, they introduced a novel parameter termed the Current Zone Indicator (CZI), which was calculated using the following equation:

where \({\upphi }_{\text{N}}\) represented normalized porosity, and \(\sqrt{\frac{\upphi }{\text{F}}}\) was referred to as the electrical radius indicator (ERI). Their findings strongly supported the notion that grouping rock samples based on CZI was an effective and more reliable method for predicting the "m" and "a" values for each category of samples. In their comprehensive study, the values of "m" ranged from 1.1 to 1.3, while "a" fell within the range of 5 to 19. This innovative approach revolutionized the characterization and categorization of carbonate rock samples, offering enhanced precision for petrophysical analysis and exploration.

Soleymanzadeh et al.30 introduced another electrical parameter known as the electrical quality index (EQI) with the primary objective of refining the classification of porosity-FRF data and improving the estimation of the cementation factor. The EQI is mathematically expressed as follows:

In which, \({\upsigma }_{\text{o}}\) represents the electrical conductivity of water-saturated rock when the electrical conductivity of the solid matrix is zero, which typically occurs in the case of clean rock samples. \({\upsigma }_{\text{w}}\) signifies the electrical conductivity of water. Their findings demonstrated that rock samples with similar EQI values exhibited identical electrical behaviour. The researchers applied this innovative parameter to a dataset comprising 112 carbonate samples, which they systematically categorized into nine distinct classes. Each class was associated with a specific equation linking FRF to porosity. Moreover, the research unveiled an intriguing observation: the plots depicting the cementation factor versus porosity yielded linear trends characterized by high determination coefficients.

Mohammadi et al.52 developed a new electrical rock typing method called the electrical zone indicator (EZI), which offers a more precise determination of reservoir electrical parameters compared to existing methods such as the EQI. The EZI approach involves a modification of EQI, reducing its reliance on porosity as a primary factor. The EZI parameter for each rock sample is calculated by evaluating the ratio of EQI to normalized porosity, as defined in Eq. (5):

By employing this formulation, EZI is anticipated to exhibit reduced dependence on porosity when compared with the EQI. Consequently, this novel concept was implemented to enhance the classification of rock samples.

Hydraulic rock typing (HRT) is a classification of rocks based on their hydraulic properties. Understanding how fluids, especially hydrocarbons, flow through reservoir rocks is essential, with HRT playing a key role in this process. It considers various petrophysical properties, including porosity, permeability, and relative permeability, to classify rock formations into distinct hydraulic units53,54,55. This approach involves grouping reservoir rocks with similar hydraulic behaviour, enabling a more accurate understanding of fluid flow within the subsurface56,57. The flow zone indicator (FZI) is a petrophysical parameter used in the oil and gas industry to classify and characterize subsurface rock formations based on their fluid flow properties. FZI is a critical tool for understanding reservoir quality, fluid distribution, and the potential for hydrocarbon production (Eqs. 6–8)58,59. It is primarily used in conjunction with well log data to analyze the flow behavior of reservoirs60,61,62.

where \({\upphi }_{\text{N}}\) represents normalized porosity, RQI and FZI are reservoir quality index and flow zone indicator, respectively.

Xu et al.63 introduced a new hydraulic rock typing method for reservoirs straddling multiple capillary windows. Their method utilized resistivity-saturation equations and Timur-Tixier’s permeability model to establish relationships between petrophysical properties. The study was tested on a gas reservoir in offshore Trinidad, showing improved accuracy in rock typing compared to existing methods. The authors emphasized the importance of considering capillary pressure behaviour in different capillary windows for reliable rock typing.

Mirzaei-Paiaman et al.54 proposed a new classification of petrophysical rock types into static and dynamic ones. The static rock type was based on primary drainage capillary pressure curves or unique water saturation, while the dynamic rock type considered fluid flow behaviour. They derived new indices for rock typing, which were tested with core data from a heterogeneous carbonate reservoir. The results demonstrated the superiority of their approach over existing models, emphasizing the importance of rock typing methods that account for wettability and capillary pressure characteristics.

Liu et al.64 introduced a novel method for petrophysical static rock typing in carbonate reservoirs based on mercury injection capillary pressure curves and principal component analysis. The relationships between petrophysical properties and parameters derived from the capillary pressure curves were established. The approach was applied to a field case in the Mishrif formation, demonstrating superior results compared to traditional methods such as the Winland plot and flow zone indicator.

Sawayama et al.65 investigated the relationship between hydraulic, electrical, and elastic properties of natural rock fractures under elevated stress conditions. They employed lattice Boltzmann simulation to unveil transitions in three-dimensional flow paths and used finite-element modelling to study the evolution of geophysical properties. The study revealed that electrical resistivity was linked with permeability and flow area irrespective of fracture roughness, while elastic wave velocity depended on roughness. These findings had potential applications in studies of geoengineering developments, seismicity, seismogenic zones, and geothermal reservoirs.

El-Sayed et al.66 described and evaluated the reservoir quality of Nubia sandstone in south-west Sinai using hydraulic and electric flow units (HFU and EFU). HFU discrimination was based on permeability and porosity relationships, while EFU differentiation relied on resistivity-porosity correlations. A petrographic investigation revealed that the studied samples were mainly quartz arenite, with varying cementation processes that affected reservoir properties. The study provided a semi-empirical relationship between complex mineral IP characteristics and permeability, enhancing the understanding of reservoir characterization.

Barach et al.67 discussed the importance of petrophysical rock typing for reservoir characterization and field development planning. They examined various approaches based on porosity and permeability relationships, including hydraulic flow unit, global hydraulic element, and Winland R35 methods. The study emphasized integrating geological features with engineering attributes to effectively distribute geological facies in reservoir models. Their proposed workflow enhanced the accuracy of reservoir estimates and forecasts.

Tong et al.68 proposed a semi-empirical reservoir permeability prediction model based on the modified generalized practical medium theory of induced polarization (MGEMTIP). The model accounted for the effects of various conductive minerals and provided a relationship between complex mineral-induced polarization characteristics and permeability. The study compared the prediction model with two electrical Kozeny-Carman (K-C) models, showing its suitability for low-porosity and low-permeability rocks containing low-resistivity minerals. This model offered a theoretical basis for reservoir permeability prediction based on electromagnetic exploration.

In summary, these studies have contributed significantly to advancing reservoir characterization and rock typing methods, providing valuable insights into understanding reservoir properties, flow behaviour, and the applicability of different approaches in various geological settings. Since over 85% of Iranian reservoirs consist of carbonate rocks, which present unique challenges due to their heterogeneity, the decision was made to focus on carbonate lithology.

In this study, a new approach for rock typing is derived to leverage the strengths of both rock typing methods (electrical and hydraulic), allowing for a more comprehensive and accurate characterization of carbonate reservoir rocks called hydraulic-electric index (HEI). This approach results in the development of distinctive electrical rock types that consider both hydraulic and electrical behaviours, improving the precision of permeability assessment and the overall classification of rocks. Two carbonate datasets have been employed. The first dataset (112 samples) is associated with a study conducted by Ragland69, and the second dataset (81 samples) pertains to one of the regions in the southwestern part of Iran. These datasets represent diverse lithologies, porosities, and permeabilities, ensuring a comprehensive performance evaluation of the HEI method. The success of the HEI approach holds great promise in revolutionizing reservoir characterization for carbonate formations. The approach can accurately represent the reservoir's heterogeneity and fluid distribution by capturing the interplay between hydraulic conductivity and electrical resistivity. Such insights are invaluable for optimizing production strategies, well placement decisions, and enhanced reservoir management.

Case study

In this study, two sets of samples were employed to demonstrate the improved accuracy in determining the permeability, porosity and FRF offered by the proposed HEI approach. The first set, dataset 1, consists of 112 samples from Ragland’s study69. The second set, dataset 2, includes 81 samples from an Iranian carbonate reservoir52. Stratigraphic information for both sample series is provided below. It is worth noting that both datasets encompass data on permeability, porosity, and FRF, as visually represented in detail in Table 1.

Dataset

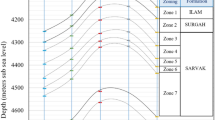

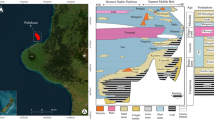

The dataset 1 is derived from the Tensleep formation, a vast carbonate reservoir in the Bighorn basin spanning Wyoming and Montana in the United States. This geological formation originates from the Pennsylvanian subperiod and predominantly comprises fossil-rich limestone and dolomite sediments formed in a shallow marine shelf environment. Within these samples, a heterogeneous blend of grainstones, packstones, wackestones, and mudstones features intricate intercrystalline, vuggy, and microporous networks. Furthermore, various diagenetic processes, such as fracturing, dissolution, and dolomitization, have further augmented the pore structures within these carbonate rocks. Core plugs have been extracted from depths between 7000 and 8000 feet, displaying 3 to 25% porosities. Additionally, permeabilities exhibit a broad range, varying between 0.02 to 534 milliDarcies (mD), as documented by Ragland69. The intricate nature of the pore structures and the presence of multiple pore types in these carbonate samples pose significant challenges when estimating electrical parameters. It is worth noting that the Tensleep formation within the Bighorn Basin is characterized by the following stratigraphic column:

Madison limestone

This layer is identified by its light gray appearance, cherty composition, and micritic limestone deposited in a deep marine basin environment during the Mississippian period.

Amsden formation

The Amsden Formation is distinguished by redbeds, sandstones, siltstones, and limestones. It originated in a tidal flat setting during the Pennsylvanian period.

Tensleep formation

The focal point of our study is fossiliferous limestones and dolomites. It was formed on a shallow marine carbonate shelf during the Pennsylvanian and exhibited wackestone-packstone textures.

Phosphoria formation

Within this layer, phosphate-rich mudrocks, chert, and siltstones could be found. These materials were deposited in a deep marine basin environment during the Permian period.

Goose egg formation

This formation consists of fossiliferous limestones and was deposited in a shallow marine setting during the Permian period.

Dataset 2 originates from the Asmari formation, a giant carbonate reservoir in the southwestern region of Iran. The Asmari formation is characterized by its diverse composition: fossil-bearing limestone, dolomitic limestone, argillaceous limestone, sandstone, and shale. This formation serves as the primary reservoir rock for numerous oil wells in the Zagros region. The Asmari formation is a complex stratigraphic unit consisting of several members and sub-members. The formation is generally divided into two main units: the Lower Asmari and the Upper Asmari.

The Lower Asmari comprises thick sequences of limestone and dolomite, with interbedded layers of marl and shale. This unit is typically characterized by its high degree of heterogeneity, with significant variations in lithology and depositional environment across different regions.

The Upper Asmari, on the other hand, is composed primarily of limestone and marl, with fewer dolomite beds. This unit is generally more homogeneous than the Lower Asmari, with a more consistent lithology and depositional environment.

Within both the Lower and Upper Asmari, several sub-members are distinguished based on lithology, thickness, and depositional environment differences. These include the Khami, Gachsaran, Sarvak, and Pabdeh sub-members, among others70,71,72.

The Asmari formation is known for its rich fossil content, which has been used to define several biozones within the formation. Biozones are specific assemblages of fossils that characterize intervals of rock, and they are helpful for correlating rocks across different regions. The biozones of the Asmari formation are based primarily on the fossil assemblages of benthic foraminifera, which are single-celled organisms that live on the seafloor. These foraminifera are particularly useful for biostratigraphy because they have a wide geographic distribution and a rapid evolutionary rate70.

The biozones of the Asmari formation include:

-

1-

Nummulites assemblage zone: This zone is characterized by abundant nummulites, which are large, disc-shaped foraminifera that can reach several centimetres in the lower part of the formation.

-

2-

Assilina assemblage zone: This zone is characterized by abundant Assilina, a genus of benthic foraminifera with a distinctive shell shape. This zone is found in the middle part of the formation.

-

3-

Operculina assemblage zone: This zone is characterized by the presence of abundant Operculina, another genus of benthic foraminifera with a distinctive shell shape. This zone is found in the upper part of the formation73.

Methodology

The primary objective of this research is to develop and validate the Hydraulic-Electric Index (HEI) for the classification and grouping of carbonate rocks. To do so, first, using Eq. (5) for EZI and the relationships outlined in Eqs. (4) and (6) for EQI and normalized porosity, FRF is calculated as follows:

By replacing Eqs. (6) and (7) for RQI and normalized porosity in Eq. (8), permeability can be derived as:

Equation (11) has been obtained by dividing Eq. (10) by Eq. (9).

For simplifying Eq. (11), the term of \(1014\frac{{\phi }^{6}}{{(1-\phi )}^{4}}\) is replaced by \({\phi }_{HEI}\):

Applying logarithm to both sides of Eq. (11) establishes the primary equation for HEI. This logarithmic transformation is often employed to simplify relationships and facilitate a clear understanding of the underlying patterns or trends in the data:

After calculating the \(\frac{K}{F}\) values by \({\phi }_{HEI}\) considering the ranges for each rock type, all samples can be categorized into the desired rock typing classes. Subsequently, by plotting K/F against \({\phi }_{HEI}\) on a log–log scale, parallel lines with a unit slope are generated. The intercept of these lines at the point where \({\phi }_{HEI}\) equals one essentially represents the mean value (\((({FZI)}^{2}.({EZI)}^{2})\)) for each rock type category. This mean value is unique to each category.

Equations (9) to (13) fully provide the required parameters for rock typing using the HEI method. The permeability, FRF, \({\phi }_{HEI}\), and \(\frac{K}{F}\) values for all the data are calculated based on Eqs. (9) to (13).

As previously stated, the innovative feature of this new concept is the seamless integration of electrical and hydraulic methods in rock classification. Electrical methods, with their detailed analysis of conductivity and resistivity traits, offer us unmatched insights into the complex electrical features of the rock samples. In parallel, hydraulic techniques effortlessly provide precious information about reservoir rocks' permeability and porosity properties. By cleverly merging these two approaches within the HEI concept, we illuminate a previously unexplored domain of knowledge that comprehensively encompasses the nature of rock types and their fluid flow behaviour within the carbonate reservoirs. It is worth emphasizing that employing the HEI enables us to achieve a more exact and reliable permeability estimation. This important parameter significantly governs the flow behaviour of fluids within reservoir rocks. Furthermore, the HEI approach can unveil concealed insights into the intricate connections between permeability, porosity, and their interdependence with hydroelectric properties, delivering an unparalleled comprehension of the petrophysical attributes of the examined rock samples.

General workflow

Figure 1 demonstrates an overview of the proposed HEI rock typing procedure workflow. After preparing the cores, they should be completely cleaned from any contamination and numbered for each dataset. Now, to start the study, routine and special tests are needed to obtain the porosity, permeability and formation resistivity factor. After obtaining the desired properties, 20% of the data are selected completely randomly to check the efficiency and validity of the studied method. In the next step, using relations 4, 5, 7, 8 and 12, EQI, EZI, RQI, FZI and \({\Phi}_{\text{HEI}}\) are obtained, respectively. Then, the HEI concept for rock typing is obtained by dividing K/F by \({\Phi}_{\text{HEI}}\) and is plotted on a logarithm-logarithm scale (K/F vs \({\Phi}_{\text{HEI}}\)). Linear regression is passed through the obtained lines, and the average (\(((\text{FZI})^{2}.(\text{EZI})^{2})\)) is obtained for each rock type. Creating tables related to extracted data for each rock type group is better. At the end, the permeability for each core in each rock type is obtained and compared with the laboratory values. All the above steps are also performed for that 20% of the selected samples.

Results and discussion

In this study, the objective is to establish a connection between the electrical and hydraulic properties of rocks so that, by having electrical parameters such as the FRF and determining the desired rock typing, it is possible to estimate hydraulic parameters, especially permeability. Considering the data scatter and the heterogeneity of carbonate rocks, extensive studies were conducted to define a parameter for rock typing the samples. After numerous investigations, it was determined that parameter ((K/F)/(\({{{\upphi}}}_{\text{HEI}}\))) exhibits higher and more acceptable accuracy in rock classification. Therefore, by defining this parameter and assigning it to all the data, its suitable range for dataset 1 was found to be from 0 to 39,956.236, and for dataset 2, it was from 0 to 993.462. The specified ranges for the selected rock typing intervals for both datasets are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. In the continuation of this section, to assess the performance and efficiency of this method, 20% of the data from each dataset were randomly selected and classified lithologically using the HEI method, and their approximate permeability values were also estimated.

When K/F is plotted against \({{{\upphi}}}_{\text{{{H}{E}{I}}}}\) on a log–log graph, a straight line with a unit slope is obtained for each type of rock. The value of the ((\({\text{(FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2}\)) can be determined from the intercept of this line at a porosity equal to 1. It is noteworthy that each of these rock types has a unique value of the parameter ((\({\text{FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2}\)), which can be easily utilized for data within each category to estimate their permeability. Samples with different ((\({\text{FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2}\)) values create parallel lines. The number of these lines corresponds to the number of reservoir rock types. All samples on the same line have uniform pore throats, indicating a single flow unit. With an increase in the numerical average of ((\({\text{FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2}\)), reservoir properties improve. According to Eq. (13), the mean value of the parameter ((\({\text{FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2}\)) is indeed the unique characteristic for each dataset.

Following Eq. (13) (\(\text{log}\left(\frac{{\text{K}}}{{\text{F}}}\right)=\text{log}{{{\upphi}}}_{\text{HEI}}+\text{log}(({\text{FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2}))\), if we assign the vertical axis to \(\frac{\text{K}}{{\text{F}}}\) and the horizontal axis to \({{{\upphi}}}_{\text{{{H}{E}{I}}}}\) in a log–log scale, adopting the concept of FZI, lines with a consistent slope are formed in parallel. To determine the parameter (\(({\text{FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2})\) in Eq. (13), it is sufficient to read the vertical axis at points where the horizontal axis equals 1. Since each of these parallel lines represents a specific rock type for different samples, the obtained parameter is considered as an average, equal to the classification number of sample groups that is specific and unique for each set of sample classifications (Figs. 2 and 3). In the next step, K/F was graphed against \({{{\upphi}}}_{\text{{{H}{E}{I}}}}\) for each dataset. It should be noted that several parallel lines have been created for both datasets in Figs. 2 and 3, representing the rock typing generated by the HEI method. By obtaining the values of these lines at the point where their horizontal axis equals 1, parameter \((({\text{FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2})\) can be determined. As mentioned earlier, since this value is unique for samples of each rock type, it is used in an averaged form. Considering the obtained values for all samples, dataset 1 was divided into nine rock types, and dataset 2 was divided into four.

Using the identified number of classes for the samples, the desired line equation can be written for each set and the accuracy of the work can be assessed according to the written equation and the resulting determination coefficient (Tables 4 and 5).

Using Eq. (11), after calculating the parameter ((\({\text{FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2}\)), the permeability values are calculated for each dataset based on the relevant rock typing to assess the accuracy and efficiency of the HEI method. Finally, they can be plotted against the actual permeability values in a log–log scale. The determination coefficient (R2) for all groups demonstrates the accuracy of this method (Figs. 4 and 5).

In the proposed workflow for the HEI method (Fig. 1), 20% of samples are randomly selected for sensitivity analysis (k-fold cross-validation). Characteristics like porosity, permeability, and the formation resistivity factor are determined for all samples. Equations from previous sections are used to calculate parameters RQI, FZI, EQI, EZI and \({{{\upphi}}}_{\text{HEI}}\). Parameter (K/F)/(\({{{\upphi}}}_{\text{HEI}}\)) is then determined for all samples and assigned to defined intervals in Tables 2 and 3 for rock types. Next, by plotting K/F against \({{{\upphi}}}_{\text{{{H}{E}{I}}}}\) on a log–log scale, creating parallel lines, and determining parameter ((\({\text{FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2}\)) for each rock type, predicted permeability values are obtained and compared with actual measured values. In the final step, the entire process is performed on the selected 20% of data, and determination coefficients are calculated for the accuracy assessment of the proposed method.

Sensitivity analysis (K-fold cross validation)

The last step includes evaluating the method’s accuracy through sensitivity coefficient analysis and determining the appropriate sample number for evaluation to assess its efficiency and precision. The recommended approach involves selecting a subset of data, precisely 20% of the entire dataset, at the study’s outset. Finally, the obtained method was applied and classifications were performed on these selected data (for 5 folds). Permeability values for these samples were determined and they were compared with the laboratory-derived actual values for each fold. This process allows for a thorough examination of the method’s efficiency and accuracy. Utilizing the HEI method involves calculating the K/F vs. \({{{\upphi}}}_{\text{{{H}{E}{I}}}}\) for selected samples using available permeability, porosity, and FRF data. The results are tabulated in Tables 6 and 7 in the Appendix section, corresponding to dataset 1 and dataset 2, respectively. The analysis then moves on to determine the rock type for each sample, allowing us to identify the parameter (average ((\({\text{FZI})}^{2}.({\text{EZI})}^{2}\))) for each one. Subsequently, Eq. (11) is applied to derive permeability values for the selected data in Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17 for dataset 1 and dataset 2, respectively. This comparative analysis employs a log–log scale, where the vertical axis represents HEI-derived permeability, and the horizontal axis represents laboratory-measured permeability. As previously explained, predicting permeability for the selected 20% of data for sensitivity analysis is essential. Following the workflow described in Fig. 1, after calculating the permeability for these samples, a comparison with actual permeability values is made on a log–log scale (Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15 for dataset 1 and 2, respectively). The average of determination coefficients of 0.883 and 0.859 are observed for datasets 1 and 2, respectively. These high determination coefficients underscore the HEI method’s precision in the permeability calculation.

Conclusions

-

This innovative research presents a study that introduces the hydraulic-electrical index (HEI) approach, a new technique for analyzing rock typing in complex carbonate reservoirs. The study demonstrates that by integrating hydraulic and electrical rock properties, i.e. permeability and formation resistivity factor, a new parameter called HEI is defined; this parameter allows researchers to achieve more precise permeability prediction and enhance the categorization of rock samples.

-

An extensive examination of two datasets containing various rock types demonstrates the wide-ranging effectiveness and adaptability of the HEI technique across various geological environments. By incorporating porosity, permeability, and resistivity data, the HEI method generates unique classification indices that successfully differentiate between rock types with similar petrophysical attributes. This integrated process enables the generation of informative graphs and aids in the development of predictive equations for accurately estimating permeability based on HEI values.

-

The concept of HEI offers a comprehensive approach to studying carbonate formations by integrating both hydraulic and electrical properties. By incorporating this method, the accuracy of rock typing is enhanced, reducing uncertainty in reservoir characterization. This innovative technique moves beyond conventional methods, providing a more holistic framework for analyzing complex carbonate formations and improving overall understanding of the field.

-

The HEI rock typing method was used to predict permeability in two datasets, with 20% of the data being cross-validated. The determination coefficients of 0.914 and 0.860 for dataset 1 and dataset 2, respectively, demonstrate the solid predictive capability of the HEI method in estimating permeability in these geological settings.

Data availability

The corresponding author will make all the data available upon a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- a:

-

Tortuosity factor

- K:

-

Permeability (mD)

- m:

-

Cementation factor

- ϕ:

-

Porosity

- CZI:

-

Current zone indicator

- ERI:

-

Electrical radius indicator

- EQI:

-

Electrical quality index

- EZI:

-

Electrical zone indicator

- FZI:

-

Flow zone indicator

- FRF:

-

Formation resistivity factor

- HEI:

-

Hydraulic-electric index

- HFU:

-

Hydraulic flow unit

- EFU:

-

Electrical flow unit

- RQI:

-

Rock quality index

- MGEMTIP:

-

Modified generalized effective medium theory of induced polarization

- R w :

-

Brine resistivity (ohm.m)

- R o :

-

Brine-saturated rock resistivity (ohm.m)

- R 2 :

-

Regression coefficient

- σ w :

-

Brine conductivity (S/m)

- σo :

-

Rock conductivity (S/m)

- ϕHEI :

-

Hydraulic-electric index porosity

- ϕN :

-

Normalized porosity

References

Lim, J. S. Reservoir properties determination using fuzzy logic and neural networks from well data in offshore Korea. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 49, 182–192 (2005).

Al-Jawad, S. N. & Saleh, A. H. Flow units and rock type for reservoir characterization in carbonate reservoir: Case study, south of Iraq. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 10, 1–20 (2020).

Kargarpour, M. A. Carbonate reservoir characterization: An integrated approach. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 10, 2655–2667 (2020).

Malki, M. L. et al. Underlying mechanisms and controlling factors of carbonate reservoir characterization from rock physics perspective: A comprehensive review. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 226, 211793 (2023).

Jamshidi Gohari, M. S., Emami Niri, M., Sadeghnejad, S. & Ghiasi-Freez, J. Synthetic graphic well log generation using an enhanced deep learning workflow: Imbalanced multiclass data, sample size, and scalability challenges. SPE J. 29, 1–20 (2023).

Bakhshian, S., Rabbani, H. S., Hosseini, S. A. & Shokri, N. New insights into complex interactions between heterogeneity and wettability influencing two-phase flow in porous media. Adv. Earth Space Sci. 47, 88187 (2020).

Li, W. et al. Pore-throat structure characteristics and its impact on the porosity and permeability relationship of Carboniferous carbonate reservoirs in eastern edge of Pre-Caspian Basin. Pet. Explor. Dev. 47, 1027–1041 (2020).

Mohammadi, M., Shadizadeh, S. R., Khaksar Manshad, A. & Mohammadi, A. H. Experimental study of the relationship between porosity and surface area of carbonate reservoir rocks. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 10, 1817–1834 (2020).

Khosravi, M. H., Emami Niri, M. & Saberi, M. R. Effects of diagenetic processes on the velocity evolution in carbonate reservoirs. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 9, 147 (2023).

Chilingarian, G. V., Mazzullo, S. J. & Rieke, H. H. Carbonate Reservoir Characterization: A Geologic-Engineering Analysis Vol. 1 (Elsevier Science, 1992).

Babadagli, T. & Al-Salmi, S. A review of permeability-prediction methods for carbonate reservoirs using well-log data. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 7, 75–88 (2004).

Tavakoli, V. Carbonate reservoir heterogeneity overcoming the challenges. In Springer Brief in Petroleum Geoscience & Engineering (ed. Tavakoli, V.) (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Emami Niri, M., Mehmandoost, F. & Nosrati, H. Pore-type identification of a heterogenous carbonate reservoir using rock physics principles: A case study from south-west Iran. Appl. Geophys. 69, 1241–1256 (2021).

Stadtmuller, M. & Jarzyna, J. A. Estimation of petrophysical parameters of carbonates based on well logs and laboratory measurements, a review. Energies 16, 4215 (2023).

Alhammadi, A. M., Gao, Y., Akai, T., Blunt, M. J. & Bijeljic, B. Pore-scale x-ray imaging with measurement of relative permeability, capillary pressure and oil recovery in a mixed-wet micro-porous carbonate reservoir rock. Fuel 268, 117018 (2020).

Faramarzi-Palangar, M., Mirzaei-Paiaman, A., Ghoreishi, S. A. & Ghanbarian, B. Wettability of carbonate reservoir rocks: A comparative analysis. Appl. Sci. 12, 131 (2021).

Rashid, F., Hussein, D., Lorinczi, P. & Glover, P. W. J. The effect of fracturing on permeability in carbonate reservoir rocks. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 152, 106240 (2023).

Khairi, H. & Harith, Z. Z. T. Influence of pore geometry, pressure and partial water saturation to electrical properties of reservoir rock: Measurement and model development. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 78, 687–704 (2011).

Norbisrath, J. H., Weger, R. J. & Eberli, G. P. Complex resistivity spectra and pore geometry for predictions of reservoir properties in carbonate rocks. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 151, 455–467 (2017).

Regnet, J. B., David, C., Robion, P. & Menendez, B. Microstructures and physical properties in carbonate rocks: A comprehensive review. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 103, 366–376 (2019).

Tariq, Z., Mahmoud, M., Al-Youssef, H. & Khan, M. R. Carbonate rocks resistivity determination using dual and triple porosity conductivity models. Petroleum 6, 35–42 (2020).

Soleymanzadeh, A., Helalizadeh, A., Jamialahmadi, M. & Soltani Soulgani, B. Development of a new model for prediction of cementation factor in tight gas sandstones based on electrical rock typing. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 94, 104128 (2021).

Kolah-Kaj, P., Kord, S. H. & Soleymanzadeh, A. The effect of pressure on electrical rock typing, formation resistivity factor, and cementation factor. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 204, 108757 (2021).

Soleymanzadeh, A., Parvin, S. & Kord, S. H. Effect of overburden pressure on determination of reservoir rock types using RQI/FZI, FZI* and Winland methods in carbonate rocks. Petrol. Sci. 16, 1403–1416 (2019).

Baraboshkin, E. E. et al. Deep convolutions for in-depth automated rock typing. Comput. Geosci. 135, 104330 (2020).

Najafi-Silab, R., Soleymanzadeh, A., Kolah-Kaj, P. & Kord, S. H. Electrical rock typing using Gaussian mixture model to determine cementation factor. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 13, 1–16 (2023).

Aman e Room, Sh., Zhonghong, Ch., Ullah, H., Ahmad, W. & Ali, M. Reservoir characteristics and controlling factors of Permian glutenite in Northern Zhongghai uplift, Junggar Basin, China. Ore Energy Resour. Geol. 15, 100025 (2023).

McKinley, J. M., Atkinson, P. M., Lloyd, C. D., Ruffell, A. H. & Worden, R. H. How porosity and permeability vary spatially with grain size, sorting, cement volume, and mineral dissolution in fluvial Triassic sandstones: The value of geostatistics and local regression. J. Sediment. Res. 81, 844–858 (2011).

Wang, J., Ye, F., Zhang, Ch. & Xi, Zh. Factors that control the reservoir quality of the Carboniferous-Permian tight sandstones in the Shilounan block, Ordos basin. Processes 11, 2279 (2023).

Soleymanzadeh, A., Jamialahmadi, M., Helalizadeh, A. & Soltani Soulgani, B. A new technique for electrical rock typing and estimation of cementation factor in carbonate rocks. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 166, 381–388 (2018).

Klyuchnikov, N. et al. Data-driven model for the identification of the rock type at a drilling bit. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 178, 506–516 (2019).

Mohammadian, E., Kheirollahi, M., Liu, B., Ostadhassan, M. & Sabet, M. A case study of petrophysical rock typing and permeability prediction using machine learning in a heterogenous carbonate reservoir in Iran. Sci. Rep. 12, 4505 (2023).

Radwan, A. E., Wood, D. A. & Radwan, A. A. Machine learning and data-driven prediction of pore pressure from geophysical logs: A case study for the Mangahewa gas field, New Zealand. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 14, 1799–1809 (2022).

Sanguino, A., Lenim, C. Petrophysical rock typing in Uinta basin using models powered by machine learning algorithms. Master of Science Degree, Norman, Oklahoma (2023).

Anselmetti, F. S., Luthi, S. & Eberli, G. P. Quantitative characterization of carbonate pore systems by digital image analysis. Am. Assoc. Petrol. Geol. 82, 1815–1836 (1998).

Garing, C. et al. Electrical and flow properties of highly heterogeneous carbonate rocks. Am. Assoc. Petrol. Geol. Bull. 98, 49–66 (2013).

Norbisrath, J. H. et al. Electrical and fluid flow properties of carbonate microporosity types from multiscale digital image analysis and mercury injection. Am. Assoc. Petrol. Geol. Bull. 99, 2077–2098 (2015).

Zhang, Z., Cai, Z., Zhang, H. & Li, J. Comparative study on hydraulic and electrical transport properties of carbonate rocks based on rock typing. J. Energy Fuels 37, 2759–2773 (2023).

Aftab, S., Leisi, A. & Kadkhodaie, A. Reservoir petrophysical index (RPI) as a robust tool for reservoir quality assessment. Earth Sci. Inform. 16, 2457–2473 (2023).

Hou, Y. et al. Numerical simulation of electrical properties of carbonate reservoirs using digital rocks. Processes 11, 2214 (2023).

Nourani, M. et al. Analytical models for predicting the formation resistivity factor and resistivity index at overburden conditions. Petrophysics 64, 353–366 (2023).

Rezaei, A. et al. Insights into the effects of pore size distribution on the flowing behavior of carbonate rocks: Linking a nano-based enhanced oil recovery method to rock typing. MDPI 10, 972 (2020).

Soleymanzadeh, A., Kolah-Kaj, P., Kord, Sh. & Monjezi, M. A new technique for determining water saturation based on conventional logs using dynamic electrical rock typing. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 196, 107803 (2021).

Archie, G. E. The electrical resistivity log as an aid in determining some reservoir characteristics. Trans. AIME 146, 54–62 (1942).

Attia, A. M. Effects of petrophysical rock properties on tortuosity factor. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 48, 185–198 (2005).

Kolah-Kaj, P., Kord, S. H. & Soleymanzadeh, A. Application of electrical rock typing for quantification of pore network geometry and cementation factor assessment. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109426 (2022).

Rezaei, H., Dehghan Monfared, A. & Soleymanzadeh, A. Cementation factor in clayey rock samples: investigation the role of clay content and determination using electrical rock classification. Appl. Clay Sci. 234, 106849 (2023).

Hassanzadeh, A. J., Javaherian, A., Pishvaie, M. R. & Nabi-Bidhendi, M. An approach to defining tortuosity and cementation factor in carbonate reservoir rocks. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 60, 125–131 (2008).

Byun, Y. H., Hong, W. T. & Yoon, H. K. Characterization of cementation factor of unconsolidated granular materials through time domain reflectometry with variable saturated conditions. Materials 12, 1340 (2019).

Akpabio, I., Atat, J., Umoren, E. & Ekemini, J. D. The reservoir rock volumetric concentration and tortuosity description of pore space of Xa field, Niger Delta basin. World J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 3, 1–13 (2023).

Rezaee, M. R., Motiei, H. & Kazemzadeh, E. A new method to acquire m exponent and tortuosity factor for microscopically heterogeneous carbonates. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 56, 241–251 (2007).

Mohammadi, M. et al. A novel electrical rock typing approach to improve estimating formation resistivity factor in carbonate rocks. NIOC Exploration Directorate (2020).

Rushing, J. A., Newsham, K. E., Blasingam, T. A. Rock typing—Keys to understanding productivity in tight gas sands. In SPE Unconventional Reservoirs Conference Keystone, Colorado (2008).

Mirzaei-Paiaman, A., Ostadhassan, M., Rezaee, R., Saboorian-Jooybari, H. & Chen, Z. H. A new approach in petrophysical rock typing. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 166, 445–464 (2018).

Prakoso, S., Irham, S., Herdiansyah, F., Burhannudinnur, M., Putra, R. A., Khairy, H., Irano, T. Rock type, diagenesis, and sonic velocity to understanding carbonate reservoirs: A case study in TKA oil field. In AIP Conference Proceedings, 2598 (2023).

Onuh, H. M., David, O. O. & Onuh, Ch. Y. Modified reservoir quality indicator methodology for improved hydraulic flow unit characterization using the normalized pore throat methodology (Niger Delta field as case study). J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 7, 409–416 (2017).

Thota, S. T., Islam, M. A. & Shalaby, M. R. Reservoir quality evaluation using sedimentological and petrophysical characterization of deep-water turbidites: A case study of Tariki sandstone member, Taranaki basin, New Zealand. Energy Geosci. 4, 13–32 (2023).

Nwokoma, E. U., Ijeh, B. I. & Amos-Uhegbu, Ch. Hydraulic flow unit characterization in sandstone reservoirs, Niger Delta, Nigeria. Earth Planet. Sci. 2, 1–10 (2023).

Abraham-A, R. M., Tassinari, C. C. C. G., Taioli, F., Rocha, H. V. & Silva, O. C. D. Reservoir quality evaluation as a measure to forecast hydrocarbon and CO2 storage prospects in Irati and Rio Bonito formations, Parana basin. Results Geophys. Sci. 14, 100059 (2023).

Amaefule, J. O. et al. Enhanced reservoir description: using core and log data to identify hydraulic (flow) units and predict permeability in uncored intervals/wells. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, 205–220 (1993).

Boualam, A. & Djezzar, S. Integration of rock types and hydraulic flow units for reservoir characterization. Application to three forks formation, Williston basin, North Dakota, USA. WILEY Online Libr. 17, 147–162 (2023).

Krivoshchekov, S. et al. Rock typing approaches for effective complex carbonate reservoir characterization. Energies 16, 6559 (2023).

Xu, Ch. et al. Connate water saturation—Irreducible or not: The key to reliable hydraulic rock typing in reservoirs straddling multiple capillary windows. SPE J. https://doi.org/10.2118/166082-MS (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Petrophysical static rock typing for carbonate reservoirs based on mercury injection capillary pressure curves using principal component analysis. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 181, 106175 (2019).

Sawayama, K. et al. Relating hydraulic-electrical-elastic properties of natural rock fractures at elevated stress and associated transient changes of fracture flow. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54, 2145–2164 (2021).

El-Sayed, A. M. et al. Rock typing based on hydraulic and electric flow units for reservoir characterization of Nubia sandstone, south-west Sinai, Egypt. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 11, 3225–3237 (2021).

Barach, B. A. B. et al. Development and Identification of Petrophysical Rock Typing for Effective Reservoir Characterization. In SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition, Lagos, Nigeria, August (2022).

Tong, X., Yan, L. & Xiang, K. A prediction method of compacted rock hydraulic permeability based on the MGEMTIP model. Minerals 13, 281 (2023).

Ragland, D. A. Trends in cementation exponents (m) for carbonate pore systems. SPWLA J. Form. Eval. Reserv. Descr. 43, 434–446 (2002).

Laursen, G. V. et al. The Asmari formation revisited: Changed stratigraphic allocation and new biozonation. In EAGE International Petroleum Conference and Exhibition (2009).

Mohammadi, Z., Mehrabi, H., Gharechelou, S., Jalali, M. & Swennen, R. Stratigraphic architecture and depositional diagenetic evolution of Oligocene-Miocene carbonate-evaporate platform in the southern margin of the Neo-Tethys Ocean, Lurestan zone of Zagros, Iran. J. Asian Earth Sci. 233, 105249 (2022).

Abdolahi, A., Bahrevar, M., Chehrazi, A., Kadkhodaie, A. & Wood, D. A. Integration of geoscience data to delineate quality of the Asmari reservoir, Iranian part of the Persian Gulf basin. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 152, 106229 (2023).

Adams, T. D., Bourgeios, F. Asmari biostoatigraphy, geological and exploration. Div, Jooc Report, 1074 (1967).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Milad Mohammadi: Investigation, Visualization, Writing-Original Draft, Conceptualization, Validation, Modeling, Mohammad Emami Niri: Writing-Review & Editing, Methodology, Validation, Supervision, Data curation, Abbas Bahroudi: Writing-Review & Editing, Validation, Supervision, Data curation, Shahin Kord: Writing-Review & Editing, Validation, Aboozar Soleymanzadeh: Writing-Review & Editing, Validation, Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Porosity, permeability, FRF, RQI, FZI, EQI, EZI, K/F and \({\upphi }_{\text{HEI}}\) of samples (except 20% data were used for validation) were used in this study are given in Table 6 (dataset 1) and Table 7 (for Iran) and 8 and 9 for 20% data were used for validation.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammadi, M., Emami Niri, M., Bahroudi, A. et al. Development of a new hydraulic electric index for rock typing in carbonate reservoirs. Sci Rep 14, 18264 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68167-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68167-3