Abstract

We conducted a retrospective study to investigate risk factors for tuberculosis care-seeking delay and diagnostic delays among pediatric pulmonary tuberculosis cases in Zhejiang Province from 2013 to 2022. Among 1274 cases, 49.61% experienced tuberculosis care-seeking delays (> 14 days from symptom onset to first hospital visit) and 14.91% faced diagnostic delays (> 14 days from initial consultation to diagnosis). The proportion of care-seeking delays ranged from 37.42 to 64.89%, while diagnostic delay fluctuated from 6.11 to 21.02%. Urban residence (OR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.62–0.98, P = 0.030), first visiting a municipal-level hospital (OR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.45–0.72, P < 0.001), and diagnostic method (OR = 0.66, 95%CI 0.52–0.84, P < 0.001) were associated with tuberculosis care-seeking delay, whereas first visiting a municipal-level hospital (OR = 2.05, 95% CI 1.49–2.80, P < 0.001) was linked to diagnostic delay. Further analysis using a 28-day cutoff point revealed that children aged 0–4 years, those from migrant populations, laboratory-confirmed patients, and those who first visited a county-level hospital were more likely to experience delays in seeking tuberculosis care. Thus, society should pay more attention to the health of rural, migrant, and 0–4-year-old children, as they are at higher risk of experiencing tuberculosis care-seeking delays.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB). According to the Global Tuberculosis Report 2023, 10.6 million TB cases were estimated in 2022, maintaining the trend from 2021 and indicating a continued increase compared to 20201. Among these TB cases, China accounts for 7.1%. TB accounts for a staggering 1.3 million deaths globally, making it the second leading cause of mortality after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), with a death toll nearly twice that of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Children aged 0–14 years represent 12% of the estimated TB cases and 16% of TB-related deaths worldwide. Owing to its nonspecific symptoms, diagnosing TB in children, a vulnerable group, can be challenging2,3,4,5. Because early symptoms usually do not lead to serious consequences or impact the ability to continue daily activities, the disease may progress for weeks or months before becoming severe enough to seek medical attention or be diagnosed as active TB6. Good knowledge of TB may enable families to immediately recognize its signs and symptoms in their children, and take action. The belief that cough is a common symptom that disappears after a certain period of time is a major reason for TB care-seeking delay. For children, parents’ attitudes towards TB greatly affect delays in seeking TB services and having a final diagnosis of TB7.

Most TB control projects rely on passive case finding which may lead to delays in care-seeking, diagnosis and even treatment8,9. However, early diagnosis and timely treatment are essential for effective TB control because delayed diagnosis may lead to increased disease severity, prolonged patient suffering, increased risk of death, and increased possibility of disease transmission in the community10,11. Delayed TB progression is a global issue affecting both developed and developing countries, stemming from TB care-seeking and diagnostic factors. The delayed progression of TB can exacerbate its contagiousness, leading to secondary infections in endemic areas10,12,13. Madebo et al.14 found that the contagiousness of patients increased with delayed progression. Infectious parameters show that in TB-endemic areas, each infection leads to 20–28 secondary infections15.

In most countries, the systematic management of TB in children is not taken seriously because it does not strongly contribute to the spread of the disease. One study showed that 20% of children suspended school attendance owing to TB cases within their families16. This indicated TB in children may have an even more severe impact. In addition, they were more likely to develop severe TB and have a unfavorable treatment outcome than adults17. Although considerable research has explored delayed TB progression in adults, research on pediatric pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) remains limited. Based on current studies, care-seeking delay among children was generally common18. This study sought to address this gap by assessing the extent of TB care-seeking and diagnostic delays among children in Zhejiang Province, China, and identifying contributing factors. The findings will inform targeted interventions to enhance pediatric PTB control efforts and mitigate the impact of the disease on children's health and well-being.

Results

Patient characteristics

In the 1274 pediatric patients with PTB included in the study, the median age was 13 years, with an IQR of 11–14 years. Geographically, the majority of children lived in rural areas, accounting for 55.26% (n = 704) of the total. The proportion of the migrant population among the patients was relatively low, at only 35.40% (n = 451). Notably, most patients (97.96%, n = 1248) were new, indicating that they had either never received anti-TB drugs or had been receiving treatment for < 1 month. In terms of case finding method, mainly due to clinical consultation, accounting for 97.25% (n = 1239), including direct treatment, referral, and follow-up. In addition, most patients (63.89%, n = 814) were clinically diagnosed. Zhejiang Province has 12 municipal PTB diagnosis and treatment hospitals; however, most patients (60.36%, n = 769) were first diagnosed in county-level units (Table 1).

Time intervals and delays among pediatric PTB

The median TB care-seeking interval was 14 days (IQR: 5–34 days), and the median diagnostic interval was 1 day (IQR: 0–8 days) (Table 2). Of the 1274 patients, 632 (49.61%) experienced TB care-seeking delay, and 190 (14.91%) experienced diagnostic delay. Overall, the interval for diagnosis was shorter than that for TB care seeking.

Trends in TB care-seeking and diagnostic delays among pediatric patients with PTB

Among pediatric PTB cases in Zhejiang Province, the proportion of TB care-seeking delays ranged from 37.42 to 64.89% (χ2 = 28.69, P = 0.001). Among them, the highest TB care-seeking delay proportion (64.89%) was found in 2013, and the lowest TB care-seeking delay proportion (37.42%) was found in 2020, with a decreasing, but not generally linear, trend (χ2 = 27.79, P < 0.001). During this period, a fluctuating upward trend from 2014 to 2017 and a steady decline from 2017 to 2020 were observed. In addition, the trend in diagnostic delay generally fluctuated, and the proportion of diagnostic delays ranged from 6.11 to 21.02% (χ2 = 19.69, P = 0.02). And the lowest proportion of diagnostic delay was in 2013 (6.11%) and the highest was in 2018 (21.02%). It indicate an upward trend (χ2 = 16.06, P = 0.007) while a downward trend was observed after 2018, but the difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 3.63, P = 0.305) (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Factors affecting TB care-seeking delay in pediatric patients with PTB

Univariate logistic regression results showed that the year of enrollment, registered residence, current residence, and hospitals of first contact may be the influencing factors for delayed TB care-seeking (P < 0.1). The statistically significant results after univariate analysis were incorporated into the multi-factor model, and the results of the step-up analysis showed that the year of enrollment, current residence, and hospitals of first contact affected TB care-seeking delay (P < 0.05). As the years progressed, patients with TB were less likely to be delayed (OR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.90–0.98, P = 0.003). The odds of care-seeking delay were 0.78 for children living in urban areas compared to those living in rural areas (OR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.62–0.98, P = 0.030), and the odds of delays were lower at the municipal level as opposed to the county level which carrying out etiological examination and recommending suspected multi-drug resistance patients to designated medical institutions at or above municipal level for examination and diagnosis (OR = 0.57, 95%CI 0.45–0.72, P < 0.001).The odds of delays were also lower among clinically diagnosed patients (OR = 0.66, 95%CI 0.52–0.84, P < 0.001) (Table 4). In our further analysis, we categorized all patients into two groups based on the TB care-seeking interval (28 days). The results revealed that enrollment year, age, diagnostic method, registered residence and the TB-designated hospitals of initial contact were significantly associated with delays in TB care-seeking. In particular, children aged 10–14 years exhibited a lower likelihood of experiencing TB care-seeking delay compared to those aged 0–4 years (OR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.33–0.90, P = 0.019). Additionally, migrant populations demonstrated a higher likelihood of experiencing delays (OR = 1.30, 95% CI 1.01–1.68, P = 0.040). The odds for delay in TB care seeking were lower at the municipal level as opposed to the county level (OR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.50–0.85, P = 0.001). The clinically diagnosed patients were less likely to experience care-seeking delay (OR = 0.67, 95%CI 0.52–0.88, P = 0.003) (Supplementary Table S1).

Factors affecting diagnostic delay in pediatric patients with PTB

Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that factors such as current residence, case finding method, and hospitals of first contact likely influenced diagnostic delay (P < 0.1). Subsequently, in stepwise regression, the hospitals of first contact emerged as a factor of diagnostic delay factor (P < 0.05). Specifically, the diagnostic delay was 2.05 times more likely at the municipal level than that at the county level (OR = 2.05, 95% CI 1.49–2.80, P < 0.001) (Table 5). When we use 28 days as a threshold for diagnostic delay, we found that the hospitals of patient first contact remained a contributing factor to diagnostic delay (OR = 1.66, 95% CI 1.10–2.52, P = 0.016) (Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

Using longitudinal pediatric TB surveillance data spanning a 10-year period in one Chinese province, this study evaluated the risk factors for TB care-seeking and diagnostic delays for pediatric patients with PTB in Zhejiang Province. Approximately 1/2 and 1/5 of pediatric PTB patients experienced TB care-seeking and diagnostic delays, respectively, using a 14-day threshold to define delays. The median TB care-seeking and diagnostic intervals for pediatric PTB were 14 days and 1 day, respectively. Multivariate analysis revealed that urban residents, children aged 10–14 years, clinically diagnosed patients, and the hospital of first contact at the municipal level were significant protective factors against TB care-seeking delay while migrant population was a risk factor. Additionally, the hospital of first contact at the municipal level was a factor influencing diagnostic delay in pediatric patients with PTB.

The median time interval from the onset of symptoms to seeking care (14 days) found in this study was lower than the 60 days reported in Ethiopia19, and 59 days reported in Ghana20, but higher than the 3 days reported in India21, and the 11 days reported in Anqing City, China22. The median diagnostic time interval was lower than the 41 days reported in India21, 6 days reported in Ethiopia19, and 45 days reported in Ghana20. These differences may be attributed to differences in the selection of the study population, sample size, sociodemographic, cultural and economic conditions of the study population, and the start time and duration of the study. The median time interval for TB care-seeking decreased by 11 days between 2013 and 2022, whereas the diagnostic time interval remained relatively stable but increased by 2 days between 2013 and 2022. These findings suggest that, over time, the state and society have placed an increasing emphasis on the dissemination of knowledge about TB, thereby reducing the time lag between the onset of symptoms and the seeking of health care by children and their parents. However, the escalating complexity of pediatric disease conditions can prolong the time interval to diagnosis. Therefore, to control the TB epidemic and reduce the time to diagnosis, consideration should be given to the development of strategies that may impact diagnostic delay, focusing on how healthcare services and professionals can help patients reach the healthcare system more quickly23,24,25.

The proportion of TB care-seeking delays for pediatric TB has increased from 2014 to 2017, potentially because of the lack of knowledge and understanding of TB among parents and guardians, leading to the inability to recognize their children's symptoms and the importance of seeking care in a timely manner. This may result to the increase in the delayed incidence of PTB in Zhejiang Province from 2014 to 2017. However, these are only potential explanations, and further research and analysis are required to determine the exact causes. As the child population includes schoolchildren who often congregate with their peers, transmission can easily occur in the event of TB exposure. In 2017, China enacted policies related to TB prevention and control in schools, which led to increased attention by national and local governments to strengthen screening and surveillance of PTB among students to avoid outbreaks of PTB in schools26,27. The development of the economy also affects health care accessibility to a certain extent, and the convenience of transport allows patients to seek medical treatment more quickly and easily across cities or provinces. These factors may potentially explain the decline in TB care-seeking delays after 2017. The diagnosis of PTB in children differs from that in adults. Respiratory tract excretion of PTB in children is low, which leads to a low diagnosis rate through sputum smears, sputum cultures, and other MTB etiological diagnosis methods. PTB is mainly transmitted through the respiratory tract, and its prevention and control are difficult. This difficulty may contribute to the increase in the diagnostic delay rate of pediatric PTB in Zhejiang Province in recent years. In 2017, TB nucleic acid amplification technology (TB-NAAT) was popularized in Zhejiang Province, which significantly improved the detection rate of PTB pathogens. The positive and negative predictive values of the TB-NAAT test was higher than those of other detection methods, and the average time taken to detect positive or negative results was only 2.5 h. Moreover, in recent years, bronchoscopy has emerged as a valuable tool for early detection of pediatric TB, enabling the inspection of tracheal and bronchial lesions while facilitating the retrieval of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples28. The upgradation of detection means led to a fluctuating downward trend in the proportion of diagnostic delays between 2018 and 2022. To achieve the mitigation of PTB, a series of patient-centered comprehensive prevention and control measures should be taken to improve treatment compliance and reduce transmission in families and society.

In recent years, the country has actively formulated a series of PTB prevention and control policies and regulations and has widely publicized them through various channels, which has increased public awareness of PTB. Therefore, as time passes, the incidence of TB care-seeking delay in children with PTB gradually decreases. According to previous research on PTB prevention and control, rural residents are more likely to experience TB care-seeking delays, which is consistent with our research results29,30,31. This correlation is mainly attributed to the low level of PTB knowledge in rural areas, compared with that in urban areas, which leads to a lack of awareness of PTB among rural children and their parents and an inadequate understanding of its symptoms, signs, and hazards. Medical resources in rural areas are relatively limited, and the level of health services is relatively low, further exacerbating the risk of TB care-seeking delay. Children who seek treatment at county-level hospitals are more likely to experience TB care-seeking delays, possibly because they mainly reside in rural areas and choose to seek treatment in nearby county-level hospitals. Moreover, TB awareness and knowledge of parents and guardians may not be robust32,33. Our study showed that laboratory-confirmed patients were more likely to experience TB care-seeking delay. This may because that the process from infection to lung lesions and then to symptoms was relatively long in laboratory-confirmed patients. In this long process, they did not go to the medical institution, indicating that they may not pay attention to the disease or the restrictions of family conditions led to their delay in seeing health care. When we analyzed pediatric TB care-seeking delay using a 28-day threshold, it was apparent that children who aged 0–4 years, laboratory-confirmed patients, migrant population and hospitals of first contact at the county level were more susceptible to such delays. These may be because children in this age group were unable to accurately communicate their symptoms. And these could also stem from lower economic and cultural levels within migrant communities, resulting in delayed healthcare awareness and action. Hospitals of first contact at the municipal level are more prone to diagnostic delays, possibly because children who visit city-level hospitals for treatment usually have more severe conditions and complex disease situations requiring additional diagnostic methods for clarification. In addition, diagnostic delay also involves factors related to the patients themselves, such as delays in the time taken for patients to seek follow-up medical attention, which may lead to delayed diagnoses. For example, patients may delay seeking follow-up medical attention because of their distance to the hospital or because parents may not pay timely attention to their children's health conditions. These factors increase the risk of delayed diagnosis of PTB in children. Previous studies have reported that active case screening in adults is beneficial for early TB detection, so patients can receive timely diagnoses and treatment, shortening the time interval for disease diagnosis34. However, given the difficulty of diagnosing TB in children, the cost-effectiveness of active screening in the pediatric population requires further investigation. Therefore, enhancing TB awareness in rural areas and paying more attention to the pediatric population are essential. Additionally, strengthening the diagnostic capabilities of hospitals is needed to ensure the timely diagnosis of patients.

This study had some limitations. First, data were collected from TBIMS, which includes data from 89 designated PTB hospitals in Zhejiang Province. Because the registered information was limited in this TB registration and reporting system, patients’ family information could not be reflected in the system. Second, no designated TB hospitals for children were available during the study period; thus, the diagnosis and treatment of diseases in younger children were generally performed in children's hospitals or non-designated hospitals. However, information on children seeking medical treatment in these hospitals cannot be registered in the system, which may result in the loss of information related to diseases in younger children.

In Conclusion, many pediatric patients with PTB still face long-term TB care-seeking and diagnostic delays in Zhejiang Province. Research has found that as time progresses, the likelihood of TB care-seeking delay in children with PTB gradually decreases. Additionally, female gender, 0–4 years old child, children living in rural areas, migrant populations and those who first received treatment in county-level hospitals were more likely to experience TB care-seeking delays. However, children who received their first diagnosis in county-level hospitals had a lower chance of experiencing diagnostic delays. Therefore, society should give more attention to the health statuses of 0–4 years old, rural, and migrant children. Additionally, their parents should pay more attention to their children in daily life and if they show any suspicious symptoms, they should be taken to the hospital promptly.

Methods

Study area

This study was conducted in Zhejiang Province, China. Zhejiang Province has an estimated total area of 103,436 square kilometers. As of 2022, the province has a population of 51.11 million, with approximately 8.68 million children aged 0–14 years.

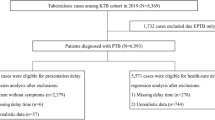

Data source

Data on all TB cases among children aged 0–14 years in Zhejiang Province were collected from the Tuberculosis Information Management System (TBIMS) which was network-based between January 2013 and December 2022. All children aged 0–14 years admitted with TB in the 89 hospitals were included in this study. Patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) were excluded. The details of each PTB cases included basic demographic information, clinical diagnostic information, and treatment classification.

Definitions

This study covered both laboratory-confirmed and clinically diagnosed PTB cases. The former is diagnosed by bacteriological evidence acquired by sputum smear and culture or a rapid diagnostic system, such as the GeneXpert MTB/RIF. The latter is diagnosed by chest imaging, epidemiological findings, and clinical symptoms along with other relevant testing35. Based on previous studies, delay in TB care-seeking is primarily caused by the patient and is defined as a period of > 14 days from the onset of PTB symptoms to the first visit to a PTB-designated hospital. Diagnostic delay is defined as a period of > 14 days from the first consultation to the diagnosis of PTB at designated medical institutions6,18,23. A cutoff point of 14 days was used analyze TB care-seeking and diagnostic delays. Urban residents were categorized as those who lived in towns and cities beyond the county level, while the rest were categorized as rural residents. The resident population was defined as individuals residing at the research site for 6 months. The migrant population comprised individuals who relocated from their original place of domicile to Zhejiang for various reasons36. First treatment patients were defined as those who had never been treated with anti-TB drugs or who had been treated with anti-TB drugs for ≤ 1 month (excluding treatment with anti-TB drugs for other diseases). Case finding method included clinical consultations, active screening, and health examinations. Clinical consultation was defined as a person with suspected symptoms of TB (cough, sputum for ≥ 2 weeks, hemoptysis, or bloody sputum) visiting a healthcare facility which including community-level medical and health institutions, comprehensive medical institutions and TB designated hospitals. When they were suspected to be TB patients, they were uniformly referred to designated TB hospitals for diagnosis and treatment. These included direct visits, referrals, and follow-up appointments. Active screening was defined as disease prevention and control institutions organizing PTB-designated medical institutions and grassroots medical and health institutions to carry out PTB screening in high-risk groups, such as those in close contact with pathogen-positive PTB and patients with HIV/AIDS within their jurisdiction. Health examination was defined as medical and health institutions at all levels and types conducting health examinations with prompt referral of PTB or suspected PTB cases to PTB-designated medical institutions for diagnosis and treatment.

General characteristics of PTB in children

Data were collected on registered year, age, sex, current residence, registered residence, treatment classification, case finding method, diagnostic method, and hospitals of first visit.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R version 4.3.2. Descriptive statistics were conducted and presented as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables and medians with interquartile range (IQR) or mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. The proportions of TB care-seeking and diagnostic delays in pediatric PTB cases from to 2013–2022 were analyzed using the Cochran-Armitage trend test. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the influencing factors of TB care-seeking delay and diagnostic delays, and variables with a P value of < 0.1 were included in the multivariate logistic regression model, and stepwise regression method was used for analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant when the P values were < 0.05.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Zhejiang Provincial Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. The Ethics Committee of the Zhejiang Provincial Centre for Disease Control and Prevention reviewed and approved the request for waiver of informed consent, as only public health surveillance data were used. This study statement confirms that all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations in the declaration.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- MTB:

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- PTB:

-

Pulmonary tuberculosis

- EPTB:

-

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis

- TBIMS:

-

Tuberculosis Information Management System

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- IQR:

-

Interquartile ranges

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- 95% CI:

-

95% Confidence interval

- TB-NAAT:

-

Tuberculosis nucleic acid amplification technology

References

WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2023. https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2023 (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2023).

Marais, B. J. & Graham, S. M. Childhood tuberculosis: A roadmap towards zero deaths. J. Paediatr. Child Health 52(3), 258–261 (2016).

Pearce, E. C., Woodward, J. F., Nyandiko, W. M., Vreeman, R. C. & Ayaya, S. O. A systematic review of clinical diagnostic systems used in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in children. AIDS Res. Treat. 2012, 401896 (2012).

Graham, S. M. et al. Childhood tuberculosis: Clinical research needs. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 8(5), 648–657 (2004).

Scheinmann, P., Refabert, L., Delacourt, C., Bourgeois, M. L. & Blic, J. D. Paediatric tuberculosis. Eur. Respir. Monogr. 2(4), 144–174 (1997).

Bello, S. et al. Empirical evidence of delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. BMC Public Health 19(1), 820 (2019).

Bojovic, O. et al. Factors associated with patient and health system delays in diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in Montenegro, 2015–2016. PLoS One. 13(3), e0193997 (2018).

WHO. The Global Plan to Stop TB 2011–2015: Transforming the Fight Towards Elimination of Tuberculosis (World Health Organization, 2010).

WHO. Systematic Screening for Active Tuberculosis: Principles and Recommendations (World Health Organization, 2013).

Farah, M. G. et al. Patient and health care system delays in the start of tuberculosis treatment in Norway. BMC Infect. Dis. 6, 33 (2006).

Getnet, F., Demissie, M., Assefa, N., Mengistie, B. & Worku, A. Delay in diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in low-and middle-income settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 17(1), 202 (2017).

Cai, J. et al. Factors associated with patient and provider delays for tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 10(3), e0120088 (2015).

Lewis, K. E., Stephens, C., Shahidi, M. M. & Packe, G. Delay in starting treatment for tuberculosis in east London. Commun. Dis. Public Health 6(2), 133–138 (2003).

Madebo, T. & Lindtjorn, B. Delay in treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: An analysis of symptom duration among Ethiopian patients. Medgenmed 18, E6 (1999).

Lusignani, L. S. et al. Factors associated with patient and health care system delay in diagnosis for tuberculosis in the province of Luanda, Angola. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 11 (2013).

Rajeswari, R. et al. Socio-economic impact of tuberculosis on patients and family in India. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 3(10), 869–877 (1999).

Marais, B. J. et al. The natural history of childhood intra-thoracic tuberculosis: A critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 8(4), 392–402 (2004).

Zhang-Ting, H. D. et al. Study on the current situation of treatment delay of childhood tuberculosis in Chongqing. Chongqing Med. 45, 25 (2016).

Demissie, M., Lindtjorn, B. & Berhane, Y. Patient and health service delay in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in Ethiopia. Bmc Public Health. 2, 7 (2002).

Osei, E., Akweongo, P. & Binka, F. Factors associated with DELAY in diagnosis among tuberculosis patients in Hohoe Municipality, Ghana. Bmc Public Health. 15, 11 (2015).

Kalra, A. Care seeking and treatment related delay among childhood tuberculosis patients in Delhi, India. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 21(6), 645–650 (2017).

Xia, D. et al. Factors associated with patient delay among new tuberculosis patients in Anqing, China. Biomed. Res. India 27(3), 651–658 (2016).

Sreeramareddy, C. T., Panduru, K. V., Menten, J. & Van den Ende, J. Time delays in diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: A systematic review of literature. BMC Infect. Dis. 9, 91 (2009).

Storla, D. G., Yimer, S. & Bjune, G. A. A systematic review of delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health 8, 15 (2008).

Lambert, M. & Van Der Stuyft, P. Delays to tuberculosis treatment: Shall we continue to blame the victim?. Citeseer 2005, 945–946 (2005).

Xu, J. et al. An outbreak of tuberculosis in a middle school in Henan, China: Epidemiology and risk factors. PLoS One. 14(11), e0225042 (2019).

Hou, J. et al. Outbreak of mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing strain in a high School in Yunnan, China. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102(4), 728–730 (2020).

Wu, Q. et al. The role of Xpert MTB/RIF using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in active screening: Insights from a tuberculosis outbreak in a junior school in eastern China. Front. Public Health. 11, 1292762 (2023).

Bogale, S., Diro, E., Shiferaw, A. M. & Yenit, M. K. Factors associated with the length of delay with tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment among adult tuberculosis patients attending at public health facilities in Gondar town, Northwest, Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 17(1), 145 (2017).

Saqib, S. E., Ahmad, M. M., Amezcua-Prieto, C. & Virginia, M. R. Treatment delay among pulmonary tuberculosis patients within the pakistan national tuberculosis control program. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 99(1), 143–149 (2018).

Lin, Y. et al. Patient delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in China: Findings of case detection projects. Public Health Action 5(1), 65–69 (2015).

Yue-Xiuyan, C. X. & Shi, Y. Investigation of the knowledge of prevention and control for tuberculosis among parents of children in middle and elementary school in Tangshan. Modern Prevent Med. 35, 12 (2008).

Chen-Xiaoyan, Z. W., Ye, Y. & Liu, Y. A survey of tuberculosis prevention knowledge of children’s parents in LuBei district. Western J. Trad. Chin. Med. 27, 8 (2014).

Hu, Z. F. et al. Mass tuberculosis screening among the elderly: A population-based study in a well-confined, rural county in Eastern China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 77(10), 1468–1475 (2023).

Jiang, H. et al. Changes in incidence and epidemiological characteristics of pulmonary tuberculosis in mainland China, 2005–2016. JAMA Netw. Open 4(4), e215302 (2021).

Li-Jia, Y. J. & Huang, L. Epidemiological characterisation of tuberculosis patients in mobile population in Fuzhou City, 2015–2020. J. Appl. Prevent. Med. 29, 2 (2023).

Funding

This study was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Project (grant numbers 2024KY902) and National-Zhejiang Health Commission Major S&T Project (grant number WKJ-ZJ-2118).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZ and FW contributed equally to this paper. FW, and BC shared joint correspondence in this work. BC, FW, LH, and YZ contributed to the study design and manuscript revision. YZ and FW contributed to the data extraction, analysis, and paper writing. BC, FW, KL, and YZ contributed to the fund acquisition and manuscript editing. DL, YL and YL contributed to the data analysis and paper finalization. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Wang, F., Huang, L. et al. Factors associated with tuberculosis care-seeking and diagnostic delays among childhood pulmonary tuberculosis in Zhejiang Province, China: a 10-year retrospective study. Sci Rep 14, 17086 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68173-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68173-5