Abstract

The eyes are widely regarded as the mirror of the soul, providing reliable nonverbal information about drives, feelings, and intentions of others. However, it is unclear how accurate emotion recognition is when only the eyes are visible and whether inferring of emotions is altered across healthy adulthood. To fill this gap, the present piece of research was directed at comparing the ability to infer basic emotions in two groups of typically developing females that differed in age. We set a focus on females seeking group homogeneity. In a face-to-face study, in a two-alternative forced choice paradigm (2AFC), participants had to indicate emotions for faces covered by masks. The outcome reveals that although the recognition pattern is similar in both groups, inferring sadness in the eyes substantially improves with age. Inference of sadness is not only more accurate and less variable in older participants, but also positively correlates with age from early through mid-adulthood. Moreover, reading sadness (and anger) is more challenging in the eyes of male posers. A possible impact of poser gender and cultural background, both in expressing and inferring sadness in the eyes, is highlighted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The eyes are believed to be the windows to the soul, delivering nonverbal, reliable information about emotional states and personal traits of a social counterpart. In other words, one can understand a person’s emotions, intentions, drives and desires by simply looking into his or her eyes. This view had been recently questioned in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to mandatory mask wearing that leaves primarily the information from the eyes available for social communication and interaction. Indeed, how accurate is emotion recognition when only the eyes are visible? Recent studies repeatedly report that reading emotions behind a mask remains efficient for some basic expressions such as happiness, but inferring other emotions such as disgust and sadness may be heavily affected1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Yet, cultural differences in emotional expressions as well as some methodological issues, such as the limitations of online research, may substantially contribute to inconsistency and low replicability of some findings, for instance, for anger recognition17,18,19.

Pre-pandemic abilities for reading language of the eyes, as assessed by the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET20; with visual input comparable with masked faces; for review see21), are shown to improve during the pandemic in female adults, as well as male and female adolescents22. In line with this, experience in viewing people wearing face masks leads to better emotion recognition in Brazilian and Swiss preschoolers aged 4 to 6 years23. This suggests a kind of implicit or passive learning. On the other hand, a comparison of emotion recognition in two independent groups of participants in May 2020 and July 2021 suggests that even after more than a year of the COVID-19 pandemic, masks remain a burden for recognizing emotions5. At the same time, individuals who self-reportedly are more practiced in watching and regularly interacting with people wearing masks are more effective and confident in recognizing facial expressions5. On the same wavelength, the face-specific event-related potentials (ERPs, N170 and P2) are reported to be affected by mask wearing, and the impact is more pronounced in individuals with less experience with masked faces24. Therefore, as expected17, the brain appears to adapt to some constraints in decoding social input.

The question arises, whether inferring facial affect from the eyes improves with life experience. By contrast with other cognitive abilities such as working memory, nonverbal social cognition is believed to remain relatively intact with age25,26. Recent research indicates a lack of deterioration or even an improvement in reading language of the eyes as assessed by the RMET in healthy aging27,28. In accordance with this, as compared to younger people (aged 18–33 years), older adults (aged 51–83 years) exhibit equal accuracy and difficulties in inferring happiness, sadness, and disgust in masked faces29. The effect of masks on emotion recognition (anger, fear, contempt, and sadness) in dynamic facial expressions does not differ between younger (18–30 years) and older (65–85 years) adults30.

It is largely unknown whether inferring emotions from the eyes is altered across more comparable intervals of the lifespan, namely, from young adulthood to middle age. To fill this gap, the present piece of research was directed at the assessment of inferring basic emotions in two groups of typically developing (TD) individuals that differ in age. In search of group homogeneity, a focus has been set on female participants, as gender differences are reported in recognition of emotions in masked faces19,31,32.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twenty-five female TD participants (Group 1) were recruited in February–March 2023 to examine gender differences in inferring emotions in masked faces19. Thirty TD female participants (Group 2) were engaged as controls for our earlier study in females with major depressive disorder (MDD) from April 2023 until February 202433. None of them had head injuries, a history of mental disorders, or regular medication. They were recruited from the local community. Participants of Group 1 were aged 22.28 ± 3.34 years (mean±standard deviation, SD; median, Mdn, 22 years, 95% confidence interval, CI [21.74; 22.82]), and those of Group 2 were aged 36.80 ± 13.12 years (Mdn, 33 years, 95% CI [31.90; 41.70]), with a significant age difference between the groups (Mann–Whitney test, U = 106.0, p < 0.001, two-tailed). German as a native language was used as one of the inclusion criteria. As cultural background affects emotion recognition in masked faces34, one of our inclusion criteria was growing up and permanently living in Germany. All observers had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. They were tested individually and were naïve as to the purpose of the study. The study was conducted in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee at the Medical School, Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. Participation was voluntary and the data was processed anonymously.

Emotions in masked faces (EMF) task

The stimuli and task are described in detail elsewhere19. In brief, photographs of six (three female and three male) Caucasians from three distinct age groups (young, middle, and older age), were taken from the Max Planck Institute FACES database35 with permission (see Fig. 1). Each depicted person displayed six emotional states (anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and neutral expressions; a surgical face mask was applied to all faces). This resulted in 36 images and a total of 108 trials (6 emotions × 2 genders × 3 age groups × 3 runs). Two alternative (correct/incorrect) responses for each trial were used, which were chosen based on the emotion confusion data1,5: angry—disgusted, fearful—sad, and neutral—happy. On each trial, in a two-alternative forced choice paradigm (2AFC), participants had to indicate the correct emotion. For avoiding possible implicit learning effects, only masked faces were used. Participants were administered a computer version of the EMF task by using Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc., Albany, CA, USA). The stimuli were presented in a pseudo-randomized order, one at a time for 2 s, in three runs separated by short breaks. Upon image offset, a correct and incorrect response appeared on the right and left sides of a screen. Participants were asked to respond as accurately as possible. Participants were carefully instructed and their understanding had been proven with pre-testing (about ten trials) performed under supervision of an examiner. No immediate feedback was provided. The testing lasted for about 15–20 min per person.

A female poser expressing six basic emotions. Faces are shown under full-face (top) and covered-by-mask conditions (bottom row). From Carbon1, the Creative Commons Attribution [CC BY] license. These images are presented for illustrative purposes only, and have not been used as experimental material in the present study.

Data processing and analysis

All data sets were checked for normality of distribution by means of the Shapiro–Wilk test. For non-normally distributed data, additionally to means and SDs, Mdns and 95% CIs were reported. For normally distributed data, a linear Pearson correlation was calculated, whereas for non-normally distributed data, a non-linear Spearman correlation was used. Inferential statistics was performed by analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and pairwise comparisons with the software package JMP (version 16; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Non-parametric statistics was performed using MATLAB (version 2023a; MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

Results

Recognition accuracy

Individual correct response rates for each emotion of the EMF task were submitted to a two-way mixed-model ANOVA with the within-subject factor Emotion (angry, happy, neutral, sad, fearful, disgusted) and between-subject factor Group (Group 1/Group 2). As expected, a main effect of Emotion was highly significant (F(5,316) = 62.74, p < 0.001, effect size, eta-squared η2 = 0.54). A main effect of Group (F(1,316) = 0.004, p = 0.951, n.s.) as well as a Group by Emotion interaction (F(5,316) = 1.78, p = 0.116, n.s.) were not significant.

Both Groups 1 and 2 exhibited a similar uneven pattern of emotion recognition: inferring facial affect in the eyes was rather accurate for fear, neutral expressions, and happiness, whereas it was less precise for disgust and sadness. This outcome indicates the replicability of our earlier findings19.

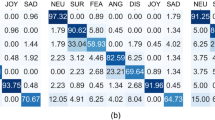

As seen in Fig. 2, pairwise comparisons revealed a significant difference between the groups in inferring sadness (Group 1, 0.691 ± 0.193; Group 2, 0.830 ± 0.162, Mdn, 0.889, 95% CI [0.769; 0.890]; U = 201, p = 0.018, here and further false discovery rate [FDR] corrected for multiple comparisons [p = 0.003, uncorrected] and two-tailed, effect size, Cohen’s d = 0.86). The difference in inferring anger (Group 1, 0.709 ± 0.146; Group 2, 0.783 ± 0.104, Mdn, 0.833, 95% CI [0.745; 0.822]; U = 257, p = 0.047, uncorrected, d = 0.56) and disgust (Group 1, 0.558 ± 0.165; Group 2, 0.650 ± 0.159; t(53) = 2.09, p = 0.041, uncorrected, d = 0.57) was also significant, but did not survive corrections for multiple comparisons and only tended to reach significance (anger, p = 0.094; disgust, p = 0.094). For other emotions, no significant differences in recognition accuracy were revealed between Group 1 and Group 2 (Table S1, Supplementary Material). This finding suggests that in inferring subtle emotions such as sadness in the eyes, experience obtained with age may be of substantial advantage.

Link of EMF task with age

Although the overall recognition rate tended to positively correlate with chronological age (Spearman’s rho, ρ(53) = 0.261, p = 0.054), only sadness showed a significant non-linear positive link with age (ρ(53) = 0.280, p = 0.039). As seen in Fig. 3, younger women exhibited rather high variability in inferring sadness. Interestingly, recognition of sadness and disgust was non-linearly correlated with each other in our sample of female TD participants (ρ(53) = 0.308, p = 0.022).

Recognition accuracy for male and female posers

Individual correct response rates were submitted to a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with the within-subject factors Emotion (angry, happy, neutral, sad, fearful, disgusted) and Gender of Poser (female/male). [Information about the gender of posers was corrupted in the data sets of two participants.] A main effect of Gender of Poser was not significant (F(1,516) = 0.94, p = 0.333, n.s.). A main effect of Emotion was highly significant (F(5,516) = 80.92, p < 0.001, effect size, η2 = 0.61) with a significant Gender by Emotion interaction (F(5,516) = 14.31, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.21).

As seen in Fig. 4, inferring sadness in the eyes of females was more accurate compared to male posers (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, z = 3.45, p = 0.003; here and further two-tailed and FDR corrected for multiple comparisons; Cohen’s d = 1.08). Inferring anger (z = 2.48, p = 0.028, d = 0.72) was also better in female eyes. By contrast, disgust was, and happiness tended to be, better recognizable in the eyes of males (disgust, z = 4.40, p < 0.001, d = 1.52; happiness, z = 1.95, p = 0.077). Inferring neutral expressions and fear did not depend on the gender of the poser (Table S2, Supplementary Material).

For female posers, sadness recognition tended to positively correlate (ρ(51) = 0.243; p = 0.077), whereas disgust recognition positively correlated (ρ(51) = 0.355, p = 0.008) with beholder age. For male posers, recognition of fear (ρ(51) = 0.326, p = 0.016) and anger (ρ(51) = 0.278; p = 0.041) positively correlated with age.

Discussion

The main outcome of the study indicates that when visual input from the eyes only is available, in healthy women, recognition of such a subtle emotional expression as sadness substantially improves across the lifespan, from young to mid-adulthood. It appears that improvement in inferring sadness in female eyes primarily contributes to this result, as sadness recognition in the eyes of male posers does not correlate with age. At first glance, it may appear paradoxical, as masks have a more pronounced impact on inferring sadness in the eyes of males compared to females.

Several factors may potentially contribute to this outcome. First of all, although both the upper (the eyes and surrounding part of a face) and lower parts of a face are believed to essentially contribute to sadness recognition36,37, its recognition accuracy as well as perceived intensity and confidence in recognition are severely affected by masks1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,38. This leads to the conclusion that not only visual information revealed in the eyes is necessary for efficient sadness recognition. This outcome appears startling, as the eyes are traditionally believed to be particularly vital for sadness recognition. In the Facial Action Coding System (FACS39), most facial action units (AUs) engaged in sadness expression come from the eye region: AU1, inner eyebrow raiser; AU4, brow furrower; AU43, upper eyelid lower; AU64, eyes down, and only AU15, lip corner depressor is beyond the eye region40.

Second, expression of emotions in the eyes is/may be gender-dependent. Social norms often encourage women to be more emotionally expressive, while men are typically socialized to exhibit less emotional variability41. This societal influence likely contributes to differences in recognition accuracy, as women, for example, are more prone to use their cheek-raisers while smiling than men, resulting in a smile that appears more genuine (also known as a true or Duchenne smile42). This nicely dovetails with the present findings as far as poorer recognition of sadness (and anger) in male posers may be explained by a lower intensity of sadness in the male eyes. By contrast, however, disgust and happiness tend to be better recognizable in male eyes, which questions the greater poignancy of females in all emotional expressions.

In addition, as pointed out earlier17, in face images routinely used in experimental settings and face databases, facial emotions are displayed by professionals who have been (i) asked and (ii) trained to express emotions. These expressions may turn out to be rather different from the natural feelings we experience and express in real life. In naturalistic environments, we are usually quite far from extreme affect demonstrations.

The ability to express (and read) emotions in the eyes had been plentifully reflected in poetry, for instance, for the eyes expressing hatred, ‘As if there were four, though they are three, stare at him hungrily’ (Alexander S. Pushkin, The Tale of Tsar Saltan, 1831; translated by Marina A. Pavlova).

Third, cultural/ethnical background in emotion expression and experience may contribute to the efficiency of emotion recognition in the eyes as well18. For instance, face masks hamper recognition of happiness in U.S. Americans but not in Japanese individuals, suggesting a higher sensitivity of Japanese people to information available in the eyes34. Individualism is reported to be associated with better recognition of (unmasked) happiness but poorer recognition of (unmasked) sadness43. On the other hand, in a U.S. sample, Asian-born participants exhibit the lowest sadness recognition accuracy compared to both Asian Americans and European Americans44. In light of these findings, the present outcome has to be taken with caution, as both expression of sadness through the eyes (faces were taken from the Max Planck Institute FACES database, German posers35) as well as inferring of sadness in the eyes by German beholders may reflect specific cultural particularities. As seen in Fig. 5, however, even within the same culture, individual differences in expression of sadness (also by the eyes) may be rather pronounced.

Pronounced differences in expression of sadness within the same cultural background. The images are taken from the MPI FACES database (Ebner et al.35; public domain). These images are presented for illustrative purposes only, and have not been used as experimental material in the present study.

In a nutshell, the present findings suggest that in inferring subtle emotional expressions (such as sadness) in the eyes, experience obtained with age, from young through middle healthy adulthood, may be of substantial benefit. At the same time, sadness recognition may be modulated by estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms45. In young women, recognition accuracy of sadness (and disgust) is higher in the follicular phase (with lower levels of estrogen and progesterone) than in the menstrual phase46,47. Overall, females are recently reported to be faster than males in sadness recognition; moreover, both female and male observers are more accurate in inferring sadness in female as compared with male faces48. A better understanding of possible alterations in reading emotions in the eyes with age calls for future tailored work in male observers.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Carbon, C.-C. Wearing face masks strongly confuses counterparts in reading emotions. Front. Psychol. 11, 566886. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566886 (2020).

Freud, E., Stajduhar, A., Rosenbaum, R. S., Avidan, G. & Ganel, T. The COVID-19 pandemic masks the way people perceive faces. Sci. Rep. 10, 22344. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78986-9 (2020).

Bani, M. et al. Behind the mask: Emotion recognition in healthcare students. Med. Sci. Educ. 31, 1273–1277 (2021).

Blazhenkova, O., Dogerlioglu-Demir, K. & Booth, R. W. Masked emotions: Do face mask patterns and colors affect the recognition of emotions?. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 7, 33 (2022).

Carbon, C.-C., Held, M. J. & Schütz, A. Reading emotions in faces with and without masks is relatively independent of extended exposure and individual difference variables. Front. Psychol. 13, 856971. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.856971 (2022).

Grahlow, M., Rupp, C. I. & Derntl, B. The impact of face masks on emotion recognition performance and perception of threat. PLoS One 17, e0262840. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262840 (2022).

Grenville, E. & Dwyer, D. M. Face masks have emotion-dependent dissociable effects on accuracy and confidence in identifying facial expressions of emotion. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 7, 15 (2022).

Maiorana, N. et al. The effect of surgical masks on the featural and configural processing of emotions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 2420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042420 (2022).

Proverbio, A. M. & Cerri, A. The recognition of facial expressions under surgical masks: The primacy of anger. Front. Neurosci. 16, 864490. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.864490 (2022).

Rinck, M., Primbs, M. A., Verpaalen, I. A. M. & Bijlstra, G. Face masks impair facial emotion recognition and induce specific emotion confusions. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 7, 83 (2022).

Tsantani, M., Podgajecka, V., Gray, K. L. H. & Cook, R. How does the presence of a surgical face mask impair the perceived intensity of facial emotions?. PLoS One 17, e0262344. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262344 (2022).

Gil, S. & Le Bigot, L. Emotional face recognition when a colored mask is worn: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 13, 174 (2023).

Ikeda, S. Social sensitivity predicts accurate emotion inference from facial expressions in a face mask: A study in Japan. Curr. Psychol. 43, 1–10 (2023).

Proverbio, A. M., Cerri, A. & Gallotta, C. Facemasks selectively impair the recognition of facial expressions that stimulate empathy: An ERP study. Psychophysiology 60, e14280. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.14280 (2023).

Ventura, M. et al. Face memory and facial expression recognition are both affected by wearing disposable surgical face masks. Cogn. Process. 24, 43–57 (2023).

Thomas, P. J. N. & Caharel, S. Do masks cover more than just a face? A study on how facemasks affect the perception of emotional expressions according to their degree of intensity. Perception 53, 3–16 (2024).

Pavlova, M. A. & Sokolov, A. A. Reading covered faces. Cereb. Cortex 32, 249–265 (2022).

Pavlova, M. A., Carbon, C.-C., Coello, Y., Sokolov, A. A. & Proverbio, A. M. Editorial: Impact of face covering on social cognition and interaction. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1150604 (2023).

Pavlova, M. A., Moosavi, J., Carbon, C.-C., Fallgatter, A. J. & Sokolov, A. N. Emotions behind a mask: The value of disgust. Schizophr 9, 1–8 (2023).

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y. & Plumb, I. The ‘Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 42, 241–251 (2001).

Pavlova, M. A. & Sokolov, A. A. Reading language of the eyes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 140, 104755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104755 (2022).

Kulke, L., Langer, T. & Valuch, C. The emotional lockdown: How social distancing and mask wearing influence mood and emotion recognition in adolescents and adults. Front. Psychol. 13, 878002. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.878002 (2022).

Ger, E. et al. Duration of face mask exposure matters: Evidence from Swiss and Brazilian kindergartners’ ability to recognise emotions. Cogn. Emot. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2024.2331795 (2024).

Prete, G., D’Anselmo, A. & Tommasi, L. A neural signature of exposure to masked faces after 18 months of COVID-19. Neuropsychologia 174, 108334 (2022).

Natelson Love, M. C. & Ruff, G. Social cognition in older adults: A review of neuropsychology, neurobiology, and functional connectivity. Med. Clin. Rev. 01, 6. https://doi.org/10.21767/2471-299X.1000006 (2016).

Reiter, A. M. F., Kanske, P., Eppinger, B. & Li, S.-C. The aging of the social mind - differential effects on components of social understanding. Sci. Rep. 7, 11046. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10669-4 (2017).

Dodell-Feder, D., Ressler, K. J. & Germine, L. T. Social cognition or social class and culture? On the interpretation of differences in social cognitive performance. Psychol. Med. 50, 133–145 (2020).

Yıldırım, E., Soncu Büyükişcan, E. & Gürvit, H. Affective theory of mind in human aging: Is there any relation with executive functioning?. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cogn. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 27, 207–219 (2020).

Faustmann, L. L., Eckhardt, L., Hamann, P. S. & Altgassen, M. The effects of separate facial areas on emotion recognition in different adult age groups: A laboratory and a naturalistic study. Front. Psychol. 13, 859464. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.859464 (2022).

Henke, L. et al. Surgical face masks do not impair the decoding of facial expressions of negative affect more severely in older than in younger adults. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 7, 63 (2022).

Grundmann, F., Epstude, K. & Scheibe, S. Face masks reduce emotion-recognition accuracy and perceived closeness. PLoS One 16, e0249792. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249792 (2021).

Huc, M. et al. Recognition of masked and unmasked facial expressions in males and females and relations with mental wellness. Front. Psychol 14, 1217736. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1217736 (2023).

Moosavi, J. et al. Reading language of the eyes in female depression. Cereb. Cortex 34, bhae253. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhae253 (2024).

Saito, T., Motoki, K. & Takano, Y. Cultural differences in recognizing emotions of masked faces. Emotion 23, 1648–1657 (2023).

Ebner, N. C., Riediger, M. & Lindenberger, U. FACES—A database of facial expressions in young, middle-aged, and older women and men: Development and validation. Behav. Res. 42, 351–362 (2010).

Bassili, J. N. Emotion recognition: The role of facial movement and the relative importance of upper and lower areas of the face. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 37, 2049–2058 (1979).

Wegrzyn, M., Vogt, M., Kireclioglu, B., Schneider, J. & Kissler, J. Mapping the emotional face. How individual face parts contribute to successful emotion recognition. PLoS One 12, e0177239. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177239 (2017).

Hysenaj, A. et al. Accuracy and speed of emotion recognition with face masks. Eur. J. Psychol. 20, 16–24 (2024).

Juslin, P. & Scherer, K. Vocal expression of affect. In The New Handbook of Methods in Nonverbal Behavior Research (eds Harrigan, Jinni et al.) 65–135 (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V. & Hager, J. C. Facial Action Coding System: Facial Action Coding System: The Manual on CD-ROM (Research Nexus, 2002).

Brody, L. R. & Hall, J. A. Gender and emotion in context. In Handbook of Emotions (eds Lewis, M. et al.) 395–408 (The Guilford Press, New York, 2008).

Hess, U. & Bourgeois, P. You smile–I smile: Emotion expression in social interaction. Biol. Psychol. 84, 514–520 (2010).

Elfenbein, H. A. & Ambady, N. When familiarity breeds accuracy: Cultural exposure and facial emotion recognition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 276–290 (2003).

Chung, J. M. & Robins, R. W. Exploring cultural differences in the recognition of the self-conscious emotions. PLoS One 10, e0136411. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136411 (2015).

Gutiérrez-Muñoz, M., Fajardo-Araujo, M. E., González-Pérez, E. G., Aguirre-Arzola, V. E. & Solís-Ortiz, S. Facial sadness recognition is modulated by estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms in healthy females. Brain Sci. 8, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8120219 (2018).

Gasbarri, A. et al. Working memory for emotional facial expressions: Role of the estrogen in young women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33, 964–972 (2008).

Guapo, V. G. et al. Effects of sex hormonal levels and phases of the menstrual cycle in the processing of emotional faces. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34, 1087–1094 (2009).

Kapitanović, A., Tokić, A. & Šimić, N. Differences in the recognition of sadness, anger, and fear in facial expressions: The role of the observer and model gender. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 73, 308–313 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to participants for their engagement in the study, Alessandro Lecchi who was an Erasmus trainee in M.A.P.’s lab and Valentina Romagnano, MSc, for assistance with the study, in particular, with recruitment and testing. We appreciate Prof. Claus-Christian Carbon, University of Bamberg, Germany, for kindly sharing the masked face stimuli.

Funding

The German Research Foundation (DFG, PA847/22-1,3 and PA847/25-1,2; FA331/31-3) to M.A.P. and A.J.F., respectively, and Reinhold Beitlich Foundation to M.A.P. and A.N.S. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. We acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Tübingen and Medical Library, Medical School, University of Tübingen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. performed testing, analyzed the data, recruited participants, wrote the manuscript. A.R. recruited participants and performed testing. A.N.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. A.J.F. contributed materials/analysis tools. M.A.P. designed the study, recruited participants, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All co-authors contributed to the writing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moosavi, J., Resch, A., Sokolov, A.N. et al. ‘The mirror of the soul?’ Inferring sadness in the eyes. Sci Rep 14, 20063 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68178-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68178-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Inferring social signals from the eyes in male schizophrenia

Schizophrenia (2024)