Abstract

This study aimed to determine whether urinary creatinine excretion rate (CER), a marker of muscle mass, is associated with diabetic retinopathy in individuals with type 2 diabetes and to ascertain whether this putative association depends on body mass index (BMI). This cross sectional study evaluated 2035 individuals with type 2 diabetes. Twenty-four-hour urine was collected. Individuals with diabetic retinopathy had lower CER and BMI values than those without. Patients in higher CER quartiles had higher BMI values and a lower prevalence of diabetic retinopathy. A significant relationship between CER and diabetic retinopathy persisted, even after adjusting for traditional risk factors, including glycated hemoglobin, diabetes duration, and hypertension, in multivariable analysis. Further adjustment for BMI did not significantly alter the association between CER and diabetic retinopathy. This study suggests that CER is inversely associated with diabetic retinopathy in individuals with type 2 diabetes, and this association is independent of BMI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy is a common diabetic complication and a major contributor to blindness in patients with diabetes mellitus1. Beyond its adverse effects on the retina, diabetic retinopathy is linked to the elevated risk of cardiovascular diseases including, coronary artery disease, stroke, and heart failure, in addition to increased mortality2,3. In patients with diabetes, quality of life may also be adversely affected by diabetic retinopathy4. Extensive evidence has revealed that poor glycemic control, prolonged diabetes, and hypertension contribute to the increased risk of diabetic retinopathy1. However, this risk has not been eliminated in clinical practice, despite rigorous efforts to control glucose and blood pressure5. Hence, evaluating other factors implicated in diabetic retinopathy is important in further comprehending the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy.

Skeletal muscle constitutes about 40% of total body weight6 and is a crucial contributor to whole-body insulin-mediated glucose disposal7, indicating its important role in metabolic disease. The recent interest in body composition has highlighted that skeletal muscle loss may have an influence on metabolic disorders and its related conditions. A prior study has shown that low muscle mass is closely related to insulin resistance and dysglycemia8. Low muscle mass is also associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D)9 and the progression of chronic kidney disease and albuminuria in patients with T2D10.

Body mass index (BMI), a marker of obesity, is a well-known risk factor for T2D5,11. Prior studies have suggested that a high BMI is a risk factor for diabetic nephropathy, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in patients with diabetes12,13,14. In contrast, several studies have reported paradoxical relationships between BMI and diabetic retinopathy, indicating an inverse association between BMI and the risk of diabetic retinopathy15,16,17. However, although BMI is a widely used indicator of adiposity, BMI does not distinguish between the relative contributions of adiposity and muscle18. Prior studies have reported that patients with a higher BMI have greater skeletal muscle mass and fat mass19,20. Thus, it is assumed that muscle mass may be linked to an association between BMI and diabetic retinopathy. However, to the best of our knowledge, the association between BMI, muscle mass, and diabetic retinopathy has not been investigated in patients with T2D.

Creatinine excretion rate (CER) assessment via 24-h urine collection is the classic method for estimating total-body skeletal muscle mass21,22. CER has been considered a reliable method for estimating muscle mass, even in patients with advanced renal failure19,23,24,25.

Therefore, this study aimed to determine whether CER is associated with diabetic retinopathy in individuals with T2D and to ascertain whether this putative association depends on BMI.

Results

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the patients with T2D. Patients with diabetic retinopathy were older and had higher systolic BP, a longer duration of diabetes, lower BMI values, higher HbA1c levels, worse albuminuria, and lower eGFR values than those without. A higher prevalence of hypertension was also noted in patients with diabetic retinopathy. A greater proportion of patients with diabetic retinopathy required insulin treatment than that of those without. In addition, patients with diabetic retinopathy had lower CER values than those without.

Age, diabetes duration, HbA1c level, albuminuria, and the prevalence rates of hypertension and insulin use were lower in patients with increased CER values in the entire patients (Table 2). BMI and the prevalence of lipid-lowering therapy were higher in patients with higher CER values. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy was lower in patients with increased CER values. In addition, significant differences were observed in diastolic BP, total cholesterol level, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, and eGFR according to CER quartile. In patients both with low BMI (< 50th percentile) and high BMI (≥ 50th percentile), age, diabetes duration, HbA1c levels, albuminuria, and the prevalence rates of hypertension, diabetic retinopathy and insulin use were lower in patients with increased CER values (Table 3). In addition, BMI values were greater in patients with higher CER values in both groups.

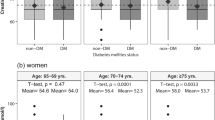

The mean values (95% CI) of CER according to the degree of diabetic retinopathy are shown in Fig. 1. In the entire patients, the mean CER values differed significantly according to retinopathy severity (absent diabetic retinopathy, 1070 mg/day; nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, 947 mg/day; proliferative diabetic retinopathy, 878 mg/day, p < 0.001). The significant differences in mean CER values were also retained according to the severity of retinopathy in patients both with low BMI (absent diabetic retinopathy, 987 mg/day; nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, 883 mg/day; proliferative diabetic retinopathy, 806 mg/day, p < 0.001) and high BMI (absent diabetic retinopathy, 1152 mg/day; nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, 1037 mg/day; proliferative diabetic retinopathy, 979 mg/day, p < 0.001).

The mean values (95% CI) of CER in patients with T2D according to the degree of diabetic retinopathy. A. The entire patients. B. Patients with low BMI (> 50th percentile) and high BMI (≥ 50th percentile). Data are presented as the geometric mean (95% CI). CER, urinary creatinine excretion; CI, confidence interval; DR, diabetic retinopathy; NPDR, nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

To evaluate the relationship between CER and diabetic retinopathy, we performed logistic regression analysis using multiple regression models (Table 4). When CER was evaluated as a continuous variable, adjustments for age, sex, smoking, hypertension, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride, HbA1c, diabetes duration, albuminuria, eGFR, and the use of OHA, lipid-lowering agent and insulin did not abolish the significant correlation between CER and diabetic retinopathy (model 1: odds ratio [OR] per 1-SD increment in the logarithmic value, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.71–0.91, p = 0.001). Additional adjustment for BMI did not significantly alter the association between CER and diabetic retinopathy (model 2: OR per 1-SD increment in the logarithmic value, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.73–0.94, p = 0.004). Likewise, the results were replicated for diabetic retinopathy when CER was treated as a categorical variable (model 2: OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77–0.99 for the highest vs. the lowest CER quartile; p = 0.031). Almost identical results were also found when systolic BP was included instead of hypertension status as a covariate in this regression model (Supplementary Table 1).

In the sensitivity analysis, we excluded participants with a deviation > 50% or > 30% from the estimated CER. On excluding participants with a > 50% deviation from the estimated CER value (n = 309), 1,726 participants were finally eligible for analysis. On excluding participants with a > 30% deviation from the estimated CER value (n = 608), 1,427 participants were finally eligible for analysis. Both exclusions did not significantly alter the relationship between CER and diabetic retinopathy (full-model ORs: 0.70 [95% CI, 0.54–0.90], p = 0.006, and 0.68 [95% CI, 0.47–0.98], p = 0.036, respectively; Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship of CER, a marker of muscle mass, with diabetic retinopathy in patients with T2D. Additionally, the association between CER and diabetic retinopathy was evaluated in relation to BMI. This study’s data demonstrated that CER was inversely associated with diabetic retinopathy in patients with T2D. The relationship between CER and diabetic retinopathy was independent of BMI.

CER acts as a substitute for muscle mass19,26. Previous studies have revealed inverse associations between CER and the risk of cardiovascular disease in the general population19 and among individuals with chronic heart failure27. A relatively low CER value has also been related to an increased risk of mortality in individuals with coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease23, and renal transplantation26. In addition, Micco et al.23 found low CER values to predict the increased risk of renal failure requiring dialysis in chronic kidney disease. These findings suggest that CER is a potentially useful marker for cardiovascular and renal outcomes.

Diabetes mellitus is related to reduced CER24,28. Previous studies have observed lower CER values in patients with diabetes than in those without26,29. Low CER values have been implicated in the increased risk of mortality in patients with T2D and concomitant nephropathy24. Furthermore, this study’s data revealed an inverse relationship between CER and diabetic retinopathy in patients with T2D. In this study, CER was associated with diabetes duration, HbA1c, eGFR, albuminuria, dyslipidemia, and the prevalence of hypertension, exhibiting consistency with the findings of previous studies24,25,29,30. The HbA1c level and diabetes duration are independent risk factors for diabetic retinopathy1. In addition, diabetic retinopathy is associated with renal impairment, dyslipidemia, and hypertension1. Thus, these factors may partially contribute to the relationship between CER and diabetic retinopathy observed in this study. However, the significant association between CER and diabetic retinopathy persisted, even after adjusting for these confounders in multivariable analysis, revealing that these factors did not substantially affect the relationship between CER and diabetic retinopathy.

Plausible explanations for the relationship between muscle mass and diabetic retinopathy exist. Skeletal muscle has recently been recognized as an endocrine organ, secreting various myokines with endocrine effects31,32. Some myokines are involved in endothelial function and oxidative stress31,32, which potentially contribute to the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy1. Among these myokines, myostatin, a negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth31,32, is suggested to induce oxidative stress33 and has been implicated in endothelial dysfunction34. Moreover, myostatin has been reported to be positively related to diabetic retinopathy in patients with T2D35. In addition, low muscle mass is possibly associated with a more poorly controlled form of diabetes, while high muscle mass reflects a milder form of diabetes, as suggested by the inverse associations of CER with HbA1c level, diabetes duration, and albuminuria found in this study (Table 2). However, the relationship between CER and diabetic retinopathy remained statistically significant after adjusting for these confounders in multivariable analysis. Another possible explanation is that visual impairment may result in reduced physical activity and muscle mass decline, although visual acuity data were unavailable in the present study.

BMI is reportedly associated with muscle mass in the general population and among individuals with chronic kidney disease19,23,29. In addition, previous investigations have reported an inverse association between BMI and diabetic retinopathy15,16,17, while the contribution of BMI to diabetic retinopathy remains inconclusive36. The risk of diabetic retinopathy was associated with a low BMI in a population-based study37. Rooney et al. also demonstrated an inverse association between BMI and diabetic retinopathy in individuals with diabetes16. However, the relationships among muscle mass, BMI, and diabetic retinopathy in patients with T2D are not fully understood. In the present study, lower CER and BMI values were each associated with diabetic retinopathy in patents with T2D. We also observed higher BMI values in patients with higher CER values. However, in subgroup analysis higher CER was associated with a lower prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in patients both with low and high BMI, and furthermore, multiple regression analyses revealed that CER was significantly associated with diabetic retinopathy independently of BMI. Therefore, our data suggest that the relationship between muscle mass and diabetic retinopathy is not significantly affected by BMI.

There are possible explanations for the association between muscle mass and diabetic retinopathy independent of BMI, although the exact mechanism is not clear. In the present study, CER was negatively associated with HbA1c level and diabetes duration in patients both with low and high BMI (Table 3). In addition, higher CER was associated with lower albuminuria and prevalence of hypertension in both groups. Because such factors play a critical role in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy1, these may partially underlie the contribution of muscle mass to the risk of diabetic retinopathy, regardless of BMI status. In addition, although individuals with higher BMI have more muscle mass19, the increase in muscle mass may be inhibited to a certain degree by the muscle lipotoxicity, inflammation, and atrophy caused by secretion of free fatty acids and adipokines from excessive fat38. Thus, the contribution of muscle mass to BMI for diabetic retinopathy may be limited. Large-scale prospective studies are necessary to investigate the dynamics between muscle mass, BMI, and diabetic retinopathy in patients with T2D.

We acknowledge the lack of direct measurement of muscle mass in this study. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scans provide detailed anatomical information about muscle structures39. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and bioelectrical impedance analysis have also been demonstrated in many studies as methods for estimating body composition40,41. CER is an indirect measure of muscle mass and may be influenced by factors such as age, gender, and diet. Thus, it could be considered a limitation that we used CER as a measure of muscle mass instead of these methods. However, using CER to assess muscle mass may have advantages. Because almost all (> 98%) of creatinine comes from skeletal muscle, CER has been recognized as one of the most specific indexes of total skeletal muscle mass in a steady state21. Other measurements, such as bioelectric impedance analysis and dual energy x-ray absorptiometry, are often considered reference methods for the assessment of muscle mass in clinical studies, but may be confounded by intramuscular adipose tissue and edema40,41. It has been suggested that even computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging may have this drawback42. However, CER is less likely to be influenced by intramuscular fat and fluid retention.

Errors in urine collections are considered a limitation in 24-h urine collection data. We performed a sensitivity analysis to minimize the impact of inaccurate collection on the results. Participants who deviated > 50 or > 30% from estimates based on a previously reported CER-estimation formula24,43 were considered to have inaccurate collections and were excluded in the sensitivity analysis. These did not substantially change our results, indicating that our main findings were not significantly affected by collection errors. Moreover, although very high or low values of the CER may reflect errors in urine collections, it may also indicate the extreme body composition.

This study has additional limitations. Because this study was cross-sectional, the causality of the associations between CER, BMI, and diabetic retinopathy could not be inferred. In addition, although patients with cardiovascular disease were excluded in our study, patients with subclinical cardiovascular disease might be included because cardiovascular disease was diagnosed on the basis of medical history and electrocardiogram44. Finally, even though several potential confounding factors were considered in the regression models, the relationship between CER, BMI, and diabetic retinopathy could still be influenced by unmeasured confounders. Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings might provide valuable information on the relationship between muscle mass, BMI, and diabetic retinopathy in patients with T2D.

In conclusion, CER, a proxy for muscle mass, is inversely associated with diabetic retinopathy in patients with T2D, and its relationship is independent of BMI. Further studies are required to evaluate the mechanisms underlying the relationship between muscle mass and diabetic retinopathy and determine whether low muscle mass contributes to an increased risk of adverse outcomes in patients with T2D and concurrent diabetic retinopathy.

Methods

Participants

In this cross-sectional study, 2042 patients with T2D who visited the diabetes clinic in our hospital were randomly enrolled between August 2019 and December 2020. T2D was diagnosed in conformity with the Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus45. Exclusion criteria in this study are presented in Fig. 2. BMI was computed by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of the height in meters. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg, or the use of antihypertensive agents. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Chonnam National University Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study was performed in conformity with the Helsinki Declaration-based ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects.

Measurement

Twenty-four-hour urine specimens and fasting (12-h) morning venous blood samples were obtained. Urine collection was initiated after voiding the bladder in the morning, and it lasted for the subsequent 24-h and included the last urination on the following morning. Using the Jaffe colorimetric assay, the urinary creatinine concentration was measured. CER was determined by multiplying the urinary creatinine concentration with the urine volume obtained via 24-h urine collection. Using the creatinine-based Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Equation46, the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was computed. To evaluate diabetic retinopathy, fundoscopy was performed by ophthalmologists following dilation of the pupils. Participants were classified into the following three groups: absent diabetic retinopathy, nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The last two groups were regarded as diabetic retinopathy.

Participants with a CER > 3,500 mg/day (n = 2) or CER < 350 mg/day (n = 5) were excluded from the analyses, as CER values > 3,500 or < 350 mg/day suggest inaccurate 24-h urine collections according to the literature43. Therefore, a total of 2,035 participants were analyzed in the present study.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or frequencies (percentages). Data with skewed distributions were log-transformed before analysis and are presented as the geometric mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). The CER and BMI values were divided into sex-stratified quartiles. Differences in categorical data were tested using the chi-squared test. For continuous data, differences between two groups were examined using Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, and differences among four groups were tested using the Kruskal–Wallis test or analysis of variance. Multivariable analyses were conducted to analyze the association between CER and diabetic retinopathy using a logistic regression model. Age, BMI, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), diabetes duration, hypertension (or systolic BP), anti-diabetic therapy, albuminuria, and eGFR were significantly associated with diabetic retinopathy in the univariable logistic regression analysis using p < 0.10 as a significance cutoff and were selected as covariates for multivariable analyses (Supplementary Table 3). Smoking, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride, and lipid-lowering therapy were also included as covariates in multivariable analyses, as these variables were previously found to affect diabetic retinopathy in the literature1,44,47. Sex was also considered as a covariate. In the multiple logistic regression analyses, we sequentially adjusted for potential confounding factors. According to the hypothesis, our study focused on two factors, CER and BMI, adjusting for other covariates in the final model. Multicollinearity was evaluated using a variance inflation factor. A variance inflation factor > 10 was excluded from the model. Interactions between CER and other covariates in the multivariable model were tested. Significant interactions between CER and any of the covariates were not detected (p for interaction > 0.05). Model 1 included adjustments for age, sex, smoking, hypertension, HbA1c, diabetes duration, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride, albuminuria, eGFR, and the use of oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs), insulin and lipid-lowering agents. Model 2 was further adjusted for BMI. For sensitivity analysis, cut-off values of > 50% or > 30% deviation from the estimated CER values were used to assess the effect of exclusion criteria more stringent than CER values > 3,500 or < 350 mg/day for inaccurate 24-h urine collections on the relationship between CER and diabetic retinopathy, based on a previously reported CER-estimation formula24,43. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cheung, N., Mitchell, P. & Wong, T. Y. Diabetic retinopathy. Lancet 376, 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62124-3 (2010).

Kramer, C. K., Rodrigues, T. C., Canani, L. H., Gross, J. L. & Azevedo, M. J. Diabetic retinopathy predicts all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in both type 1 and 2 diabetes: Meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Care 34, 1238–1244. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-0079 (2011).

Cheung, N. & Wong, T. Y. Diabetic retinopathy and systemic vascular complications. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 27, 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.12.001 (2008).

Brown, M. M., Brown, G. C., Sharma, S. & Shah, G. Utility values and diabetic retinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 128, 324–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00146-4 (1999).

Beulens, J. W. et al. Effects of blood pressure lowering and intensive glucose control on the incidence and progression of retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 52, 2027–2036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1457-x (2009).

Frontera, W. R. & Ochala, J. Skeletal muscle: A brief review of structure and function. Calcif. Tiss. Int. 96, 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-014-9915-y (2015).

Merz, K. E. & Thurmond, D. C. Role of Skeletal muscle in insulin resistance and glucose uptake. Compr. Physiol. 10, 785–809. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c190029 (2020).

Srikanthan, P. & Karlamangla, A. S. Relative muscle mass is inversely associated with insulin resistance and prediabetes. Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 2898–2903. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-0435 (2011).

Son, J. W. et al. Low muscle mass and risk of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and older adults: Findings from the KoGES. Diabetologia 60, 865–872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-4196-9 (2017).

Low, S. et al. Low muscle mass is associated with progression of chronic kidney disease and albuminuria - An 8-year longitudinal study in Asians with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 174, 108777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108777 (2021).

Garvey, W. T. et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists and american college of endocrinology position statement on the 2014 advanced framework for a new diagnosis of obesity as a chronic disease. Endocr. Pract. 20, 977–989. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP14280.PS (2014).

Khalangot, M., Tronko, M., Kravchenko, V., Kulchinska, J. & Hu, G. Body mass index and the risk of total and cardiovascular mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes: A large prospective study in Ukraine. Heart 95, 454–460. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2008.150524 (2009).

Maric, C. & Hall, J. E. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and diabetic nephropathy. Contrib. Nephrol. 170, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1159/000324941 (2011).

Eeg-Olofsson, K. et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes: An observational study in 13,087 patients. Diabetologia 52, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-1190-x (2009).

Chaturvedi, N. & Fuller, J. H. Mortality risk by body weight and weight change in people with NIDDM. The WHO Multinational Study of Vascular Disease in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 18, 766–774. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.18.6.766 (1995).

Rooney, D. et al. Body mass index and retinopathy in Asian populations with diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol 52, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-014-0602-2 (2015).

Lim, L. S. et al. C-reactive protein, body mass index, and diabetic retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 4458–4463. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.09-4939 (2010).

Nuttall, F. Q. Body mass index: Obesity, BMI, and health: A critical review. Nutr. Today 50, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1097/NT.0000000000000092 (2015).

Oterdoom, L. H. et al. Urinary creatinine excretion, an indirect measure of muscle mass, is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the general population. Atherosclerosis 207, 534–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.010 (2009).

Romero-Corral, A., Lopez-Jimenez, F., Sierra-Johnson, J. & Somers, V. K. Differentiating between body fat and lean mass-how should we measure obesity?. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 4, 322–323. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpendmet0809 (2008).

Heymsfield, S. B., Arteaga, C., McManus, C., Smith, J. & Moffitt, S. Measurement of muscle mass in humans: validity of the 24-hour urinary creatinine method. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 37, 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/37.3.478 (1983).

Wang, Z. M., Gallagher, D., Nelson, M. E., Matthews, D. E. & Heymsfield, S. B. Total-body skeletal muscle mass: evaluation of 24-h urinary creatinine excretion by computerized axial tomography. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 63, 863–869. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/63.6.863 (1996).

Di Micco, L. et al. Urine creatinine excretion and clinical outcomes in CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 8, 1877–1883. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.01350213 (2013).

Sinkeler, S. J. et al. Creatinine excretion rate and mortality in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. Diabetes Care 36, 1489–1494. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-1545 (2013).

Ix, J. H. et al. Urinary creatinine excretion rate and mortality in persons with coronary artery disease: The Heart and Soul Study. Circulation 121, 1295–1303. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.924266 (2010).

Oterdoom, L. H. et al. Urinary creatinine excretion reflecting muscle mass is a predictor of mortality and graft loss in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 86, 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0b013e3181788aea (2008).

ter Maaten, J. M. et al. Creatinine excretion rate, a marker of muscle mass, is related to clinical outcome in patients with chronic systolic heart failure. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 103, 976–983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-014-0738-7 (2014).

Sun, Z., Liu, L., Liu, N. & Liu, Y. Muscular response and adaptation to diabetes mellitus. Front. Biosci. 13, 4765–4794. https://doi.org/10.2741/3038 (2008).

Tynkevich, E. et al. Decrease in urinary creatinine excretion in early stage chronic kidney disease. PLoS One 9, e111949. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111949 (2014).

Carter, C. E. et al. Influence of urine creatinine on the relationship between the albumin-to-creatinine ratio and cardiovascular events. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 7, 595–603. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.09300911 (2012).

Severinsen, M. C. K. & Pedersen, B. K. Muscle-organ crosstalk: The emerging roles of myokines. Endocr. Rev. 41, 594–609. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnaa016 (2020).

Pang, B. P. S., Chan, W. S. & Chan, C. B. Mitochondria homeostasis and oxidant/antioxidant balance in skeletal muscle-do Myokines play a role?. Antioxidants (Basel) 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10020179 (2021).

Sriram, S. et al. Modulation of reactive oxygen species in skeletal muscle by myostatin is mediated through NF-kappaB. Aging Cell 10, 931–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00734.x (2011).

Butcher, J. T. et al. Effect of myostatin deletion on cardiac and microvascular function. Physiol. Rep. 5, 1. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13525 (2017).

Chung, J. O., Park, S. Y., Chung, D. J. & Chung, M. Y. Serum myostatin levels are positively associated with diabetic retinopathy in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Complicat. 34, 107592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107592 (2020).

Diabetes Prevention Program Research, G. The prevalence of retinopathy in impaired glucose tolerance and recent-onset diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabet Med 24, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02043.x (2007).

Jee, D., Lee, W. K. & Kang, S. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008–2011. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 6827–6833. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-12654 (2013).

Pellegrinelli, V. et al. Human adipocytes induce inflammation and atrophy in muscle cells during obesity. Diabetes 64, 3121–3134. https://doi.org/10.2337/db14-0796 (2015).

Mitsiopoulos, N. et al. Cadaver validation of skeletal muscle measurement by magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(85), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1998.85.1.115 (1998).

Khalil, S. F., Mohktar, M. S. & Ibrahim, F. The theory and fundamentals of bioimpedance analysis in clinical status monitoring and diagnosis of diseases. Sensors (Basel) 14, 10895–10928. https://doi.org/10.3390/s140610895 (2014).

Levine, J. A. et al. Measuring leg muscle and fat mass in humans: Comparison of CT and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(88), 452–456. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2000.88.2.452 (2000).

Watt, M. J., Heigenhauser, G. J. & Spriet, L. L. Intramuscular triacylglycerol utilization in human skeletal muscle during exercise: is there a controversy?. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(93), 1185–1195. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00197.2002 (2002).

Ix, J. H. et al. Equations to estimate creatinine excretion rate: The CKD epidemiology collaboration. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 6, 184–191. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.05030610 (2011).

Itoh, H. et al. Achieving LDL cholesterol target levels <1.81 mmol/L may provide extra cardiovascular protection in patients at high risk: Exploratory analysis of the Standard Versus Intensive Statin Therapy for Patients with Hypercholesterolaemia and Diabetic Retinopathy study. Diabetes Obes Metab 21, 791–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13575 (2019).

Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 26 Suppl 1, S5–S20, https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5 (2003).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150, 604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 (2009).

Cai, X. et al. The association of smoking and risk of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Endocrine 62, 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-018-1697-y (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2021R1F1A1062776) and Chonnam National University Hospital Biomedical Research Institute (BCRI24035).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.O.C. designed the study, analyzed data, drafted the manuscript, and approved its final version. S.Y.P. and M.Y.C. contributed to the statistical analyses and interpretation of data. J.O.C., B.K, D.H.C., and D.J.C. acquired data. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, J.O., Park, SY., Kim, Bn. et al. Association of urinary creatinine excretion and body mass index with diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep 14, 17175 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68220-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68220-1