Abstract

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is released from injured cells and aggravates inflammation. Patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) often develop pneumonia and respiratory failure, and require oxygen therapy (OT), including mechanical ventilation (MV). It remains unclear whether cfDNA predicts the risk of receiving OT or MV in COVID-19 patients. Therefore, we hypothesized that circulating cfDNA levels could reflect the severity of respiratory failure and determine a therapeutic approach for oxygenation in patients with COVID-19. We analyzed cfDNA levels in serum samples from 95 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 at Showa University Hospital (Tokyo, Japan). cfDNA levels were assessed by measuring the copy numbers of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and nuclear DNA (nDNA) using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Both cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA levels were negatively correlated with adjusted SpO2 for FiO2 (SpO2/FiO2 ratio). Elevated cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA levels were associated with the requirement for OT or MV during patient admission. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA levels were independent risk factors for OT and MV. These results suggest that both serum cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA could serve as useful early biomarkers to indicate the necessity of OT or MV in patients with COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is a global pandemic that has resulted in more than 775 million confirmed cases and 7.0 million deaths as of June 09, 2024 (https://covid19.who.int/). COVID-19 presents a broad spectrum of clinical features ranging from asymptomatic disease to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)1. Critical criteria for hospitalization includes respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath and dyspnea, abnormal chest imaging, and low oxygen saturation (SpO2)1. Therefore, oxygen therapy (OT), including mechanical ventilation (MV), is a key treatment option for patients hospitalized with respiratory failure stemming from COVID-19.

Accumulating evidence suggests that cellular DNA, including both nuclear DNA (nDNA) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), is secreted from cells and circulates systemically under various pathophysiological conditions, such as exercise, obesity, autism spectrum disorder, trauma, sepsis, cancer, and myocardial infarction2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Circulating cell-free (cf)-mtDNA levels are also increased in geriatric syndromes with viral infection9,10. In the respiratory system, the level of circulating cf-nDNA or cf-mtDNA is associated with disease severity and the prognosis of pulmonary diseases such as ARDS, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and lung cancer3,4,11,12,13,14,15. Notably, released extracellular DNA acts as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) that can drive molecular processes, leading to the exacerbation of inflammatory responses and organ injuries4,16,17,18.

Recent reports have suggested that the plasma levels of cf-mtDNA and cf-nDNA are increased in COVID-19 patients19,20,21,22, and that cf-mtDNA may serve as a potential early indicator of poor COVID-19 outcomes19. In addition, total cfDNA (including both cf-mtDNA and cf-nDNA) likely provides a comprehensive profile of tissue injury20. However, it remains unclear whether circulating cf-mtDNA and cf-nDNA can serve as useful early biomarkers for initiating oxygen administration, not limited to MV but also include other devices such as masks, in patients with COVID-19. In this study, we hypothesized that circulating cfDNA levels are associated with the severity of respiratory failure and are inversely associated with SpO2 in COVID-19 patients. Therefore, this study aimed to test whether circulating cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA could serve as useful biomarkers to indicate the necessity of OT or MV in COVID-19 patients.

Results

Enrolled patients

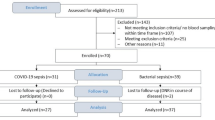

We enrolled 345 patients with COVID-19 hospitalized at Showa University Hospital between April 2020 to April 2021. SARS-CoV-2 infections were confirmed by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with samples obtained from nasopharyngeal swabs23,24. Patients with the following criteria were excluded: (i) inability to collect pretreatment serum, (ii) unknown outcomes due to transfer to other hospitals, (iii) age < 18 years, and (iv) pregnancy. After application of the exclusion criteria, 95 patients were included in the analysis.

Correlation between cfDNA levels and SpO2

Since SpO2 is a key clinical parameter for evaluating the severity of COVID-19 and respiratory failure, we first investigated the relationship between serum cfDNA (cf-mtDNA and cf-nDNA) levels and SpO2 in enrolled COVID-19 patients upon admission. Serum was isolated from the patients’ blood within 6 h of admission. SpO2 was negatively correlated with cf-nDNA (R: − 0.256, P = 0.012; Fig. 1a), whereas no significant association was found between SpO2 and cf-mtDNA (R = − 0.123, P = 0.233; Fig. 1b). Given that some patients received oxygen during the SpO2 measurement, we examined the relationship between the SpO2/ fraction of inspiratory oxygen (FiO2) ratio and cfDNA25,26. SpO2/FiO2 ratios negatively correlated with both circulating cf-nDNA (R = − 0.423, P < 0.001; Fig. 1c) and cf-mtDNA (R = -0.284, P = 0.005; Fig. 1d).

Correlation between cfDNA and blood oxygen levels. Blood was obtained from COVID-19 patients within 6 h of admission, followed by serum isolation. Total cfDNA isolated from serum was analyzed by qPCR for the quantification of cf-nDNA and -mtDNA. Scatter plots show the correlation between SpO2 and (a) cf-nDNA, and (b) cf-mtDNA; between SpO2/FiO2 ratio and (c) cf-nDNA, and (d) cf-mtDNA.

We also investigated the relationship between circulating cfDNA levels and clinically used biomarkers measured upon admission. cf-nDNA levels were positively associated with circulating neutrophil counts, d-dimer, ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein (CRP), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), and Krebs von den Lungen 6 (KL-6) levels (Supplementary Fig. 1). Similarly, cf-mtDNA levels positively correlated with circulating neutrophil counts, d-dimer, LDH, CRP, and KL-6 levels (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, cf-mtDNA levels did not significantly correlate with ferritin and BNP levels (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Furthermore, we carried out multiple regression analyses to determine the clinical indicators independently associated with cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA levels. Among the blood markers that were significantly correlated with cf-nDNA levels (Supplementary Fig. 1), only neutrophil count remained independently associated (Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, only d-dimer levels were independently associated with cf-mtDNA levels (Supplementary Table 2).

Comparison of circulating cfDNA levels in COVID-19 patients by disease severity

Given the negative correlation between cfDNA and SpO2 upon admission, we examined the levels of circulating cfDNA based on the severity of COVID-19. The enrolled patients were categorized as “moderate,” “severe,” and “critical” based on the severity scoring system and classification from previous reports (Table 1)27,28,29. Moderate cases included patients with pneumonia who did not require OT; severe cases included those who required OT; and critical cases were individuals admitted to the intensive care unit requiring MV with or without extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Figure 2 illustrates the study flow diagram, and Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study participants. Among the 95 patients, 41 (43.2%) received various types of OT, including oxygen supplementation via a nasal cannula, mask, or MV, during hospitalization, whereas 54 (56.8%; moderate group) did not receive any OT (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Among those who received OT, 24 (25.3%; severe group) received OT without MV and 17 (17.9%; critical group) required MV. Within the critical group, ECMO was used in four patients (4.2%), and three patients (3.2%) died during hospitalization. The duration from admission to death for the three deceased patients was 29, 35, and 81 days. Significant differences were observed among the three groups in terms of age (P < 0.001), sex (P = 0.048), smoking status (P = 0.006), and frequency of comorbidities with COPD (P = 0.018) and diabetes mellitus (DM) (P = 0.005). The median age of the moderate group was significantly lower than that of the severe and critical groups (P = 0.002 and P = 0.003, respectively). The moderate group tended to have more females and never smokers, whereas the critical group showed a higher frequency of comorbidities with COPD and DM.

We first compared serum cfDNA levels between COVID-19 patient groups. Notably, significant differences were observed among the three groups for both types of cfDNA (cf-nDNA, P = 0.016; cf-mtDNA, P = 0.012; Fig. 3a and b). Critical COVID-19 cases (630.6 [440.5–1,463.8] copies/µL) had higher cf-nDNA levels than moderate cases (349.4 [224.2–618.7] copies/µL) (P = 0.004, Fig. 3a). No significant differences in cf-nDNA levels were observed between moderate and severe cases (351.4 [282.4–922.0] copies/µL) as well as that between severe and critical cases (P = 0.389 and P = 0.088, respectively; Fig. 3a). Similarly, the levels of cf-mtDNA in critical cases (1,073.4 [639.5–2,572.5] copies/µL) were higher than those in moderate cases (543.5 [298.9–1,035.2] copies/µL) (P < 0.001, Fig. 3b). No significant differences were observed in cf-mtDNA levels between moderate and severe cases (632.9 [298.9–1,805.9] copies/µL) or between severe and critical cases (P = 0.360 and P = 0.070, respectively; Fig. 3b). The cfDNA levels of critical cases (N = 17) were further compared between the high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) group (PEEP ≥ 12 cmH2O) (N = 9) and the low PEEP group (PEEP < 12 cmH2O) (N = 8). Three patients receiving ECMO were included in the high PEEP group. The results for cf-nDNA were 1138.7 [469.7–1,463.9] copies/µL in the high PEEP group and 561.7 [491.7–2,085.3] copies/µL in the low PEEP group, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.958; Supplementary Fig. 3a). For cf-mtDNA, the high PEEP group was 1,228.6 [519.1–4,357.5] copies/µL, while the low PEEP group was 1,073.4 [1009.9–1405.5] copies/µL. There was no significant difference in cf-mtDNA levels between the two groups (P = 0.985; Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Serum levels of cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA in COVID-19 patients. cf-nDNA (a) and cf-mtDNA (b) were measured in COVID-19 patients, including those with moderate (N = 54), severe (N = 24), and critical disease (N = 17). Data are presented as medians with boxes indicating upper and lower quartiles, whiskers indicating extremes, and with P values calculated by Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test.

Increased cfDNA levels in COVID-19 patients who required OT

To investigate whether receiving OT accounted for the increase in circulating cfDNA in COVID-19 patients, all 95 patients were grouped into two categories; those who underwent OT and those who did not (non-OT) (Supplementary Table 3). The OT group was characterized by older age (P < 0.001) and comprised a higher proportion of males (P = 0.043) than the non-OT group. Significant differences in smoking status were also observed (P < 0.001). There were 38 (70.4%) never smokers in the non-OT group and 15 (36.6%) in the OT group. Body mass index (BMI) was also generally higher in the OT group than in the non-OT group, although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.058). Additionally, the OT group had more comorbidities, such as interstitial pneumonia and DM than the non-OT group (P = 0.019 and P = 0.001, respectively). The levels of cf-nDNA were significantly higher in the OT group as compared to the non-OT group (549.9 [289.0–1158.2] copies/µL versus 349.4 [224.2–618.7] copies/µL) (P = 0.026; Fig. 4a). In the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, the area under the curve (AUC) of cf-nDNA for OT was 0.634 (P = 0.005; Fig. 4c), and an optimal cutoff value of 843.5 copies/µL distinguished those in the OT group from those in the non-OT group with a sensitivity of 36.6% and specificity of 90.7%. Patients with a cf-nDNA level ≥ 843.5 copies/µL had increased odds of receiving OT (odds ratio [OR] 5.65, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.84–17.29, P = 0.001). cf-mtDNA levels were significantly higher in the OT group than in the non-OT group (953.4 [429.3–1,873.4] copies/µL versus 543.5 [298.9–1,035.2] copies/µL) (P = 0.021; Fig. 4b). The AUC of cf-mtDNA for OT was 0.639 (P = 0.029; Fig. 4d), and a cutoff value of 945.2 copies/µL distinguished those with OT from those without OT with a sensitivity of 53.7% and specificity of 74.1%. Patients with a cf-mtDNA level ≥ 945.2 copies/µL had increased odds of receiving OT (OR 3.31, 95% CI 1.39–7.85, P = 0.006).

Elevated cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA levels in COVID-19 patients subject to OT. cf-nDNA (a) and cf-mtDNA (b) were measured in COVID-19 patients including those with OT (N = 41) and non-OT (N = 54). Data are presented as medians with boxes indicating upper and lower quartiles, whiskers indicating extremes, and with P values calculated by Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test. (c) ROC curves for cf-nDNA to predict OT. The AUC was 0.634 for OT with a cf-nDNA level of 843.5 copies/µL. (d) ROC curves for cf-mtDNA to predict OT. The AUC was 0.639 for OT with a cf-mtDNA level of 945.2 copies/µL.

Given that established clinical blood biomarkers such as LDH, d-dimer, and ferritin have been associated with disease severity in COVID-19 patients30,31,32,33,34, we tested whether these biomarkers, along with cfDNA, could predict the risk of receiving OT. For every 100 copies increase in cf-nDNA level, patients had increased odds of receiving OT after adjusting for age and sex (OR 1.11, 95% CI 1.00–1.24, P = 0.033) (Table 2). Other markers, including neutrophil count, d-dimer, ferritin, LDH, and CRP levels were also significantly associated with OT after adjustment (Table 2). Notably, LDH was the most strongly associated with increased odds of receiving OT among the markers tested (OR 4.32, 95% CI 2.04–9.12, P < 0.001) (Table 2). Although univariate analyses showed that both KL-6 and cf-mtDNA were associated with OT, these associations were no longer significant in the multivariable analysis after adjustment (Table 2).

Increased cfDNA levels in COVID-19 patients who required MV

To investigate whether receiving MV contributed to an increase in circulating cfDNA levels in COVID-19 patients, we categorized all 95 subjects into two groups: patients who received MV and those who did not (non-MV) (Supplementary Table 4). The MV group was characterized by older age (P = 0.020) and a higher proportion of males (P = 0.022) than the non-MV group. Significant differences in smoking status were evident between the MV and non-MV groups (P = 0.044), with never smokers constituting 47 (60.2%) of the non-MV group and 6 (35.3%) in the MV group. Moreover, patients in the MV group had more comorbidities such as hypertension and COPD than those in the non-MV group (P = 0.027 and P = 0.005, respectively). The levels of cf-nDNA were significantly higher in patients who received MV than in the non-MV group (630.6 [440.5–1,463.8] copies/µL versus 351.4 [230.4–646.5] copies/µL) (P = 0.006; Fig. 5a). In ROC analysis, the AUC of cf-nDNA for MV was 0.712 (P = 0.002; Fig. 5c), and an optimal cutoff value of 389.4 copies/µL distinguished those with MV from those without MV with a sensitivity of 82.4% and specificity of 59%. Patients with a cf-nDNA level ≥ 389.4 copies/µL had increased odds of receiving MV (OR 6.36, 95% CI 1.67–24.14, P = 0.002). The levels of cf-mtDNA were significantly higher in patients with MV than in the non-MV group (1,073.4 [639.5–2,572.5] copies/µL versus 560.8 [330.3–1,078.4] copies/µL) (P = 0.004; Fig. 5b). The AUC of cf-mtDNA for MV was 0.720 (P = 0.005, Fig. 5d), and a cutoff value of 945.2 copies/µL distinguished those with MV from those without MV with a sensitivity of 70.6% and specificity of 69.2%. Patients with a cf-mtDNA level ≥ 945.2 copies/µL had increased odds of receiving MV (OR 6.87, 95% CI 2.01–23.4, P < 0.001).

Elevated cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA levels in COVID-19 patients subject to MV. cf-nDNA (a) and cf-mtDNA (b) were measured in COVID-19 patients including those with MV (N = 17) and non-MV (N = 78). Data are presented as medians with boxes indicating upper and lower quartiles, whiskers indicating extremes, and with P values calculated by Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test. (c) ROC curves for cf-nDNA to predict MV. The AUC was 0.712 for MV with a cf-nDNA level of 389.4 copies/µL. (d) ROC curves for cf-mtDNA to predict MV. The AUC was 0.720 for MV with a cf-mtDNA level of 945.2 copies/µL.

We also assessed the association between cfDNA levels and clinically established measures with MV. For every 100 copies increase in cf-nDNA level, patients displayed increased odds of receiving MV after adjusting for age and sex (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.03–1.27, P = 0.008). Similarly, for every 100 copies increase in cf-mtDNA level, patients had increased odds of receiving MV after adjustment (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01–1.12, P = 0.008) (Table 3). Similar to the observed prediction for OT, neutrophil count, d-dimer, ferritin, LDH, CRP, and KL-6 levels were significantly associated with MV after adjustment. Notably, among the tested markers, LDH had the highest predictive value (OR, 2.38) for MV (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we observed that serum cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA levels were elevated in COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure. Elevated cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA levels were also associated with requiring OT or MV in COVID-19 patients. Moreover, both cfDNA levels were negatively correlated with the SpO2/FiO2 ratio. Although both cfDNA types were independent risk factors for OT and MV, LDH had the highest OR among the clinically used inflammatory and cell injury biomarkers known to increase in COVID-19.

The data from the present study cannot be used to determine the cell types responsible for the secretion of nDNA and mtDNA, or the underlying mechanisms by which nDNA and mtDNA are released from cells. Accumulating evidence, however, suggests that DNA is released from cells that undergo apoptosis or necrosis 35,36. In addition, recent studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 triggers neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) 37 and that NETosis, a unique form of cell death characterized by the release of decondensed chromatin and granular contents to the extracellular space, increased in patients with COVID-1938. Our data showed an independent association between circulating neutrophil counts and cf-nDNA levels, suggesting that neutrophils may be one of sources releasing DNA in patients with COVID-19. We also observed that the levels of d-dimer, a fibrin degradation product of fibrinolysis, were independently associated with cf-mtDNA levels. A recent meta-analysis showed that circulating d-dimer levels increase in COVID-19 patients with venous thromboembolism, and are associated with disease severity39. Platelets of thrombi can release mtDNA accompanied by d-dimer during fibrinolysis, as mature platelets contain mitochondria but not nuclei40,41,42. These reports may partly explain why the d-dimer levels were an independent predictor of cf-mtDNA, but not cf-nDNA, in our study. However, it remains unclear whether circulating cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA levels increase as a result of the severity of illness alone, or whether mtDNA actively contributes to the pathogenesis of COVID-19 in patients with DAMPs4,18. Further studies are required to confirm this hypothesis.

Our findings are consistent with those of recent studies demonstrating that plasma cf-mtDNA and cf-nDNA levels are associated with disease severity in COVID-19 patients19,20. Moreover, we demonstrated that serum cf-mtDNA and cf-nDNA are early predictive markers of the necessity of oxygen administration in COVID-19 patients. Interestingly, a recent report showed significantly higher circulating cfDNA levels in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, but not in those with influenza or respiratory syncytial virus20. Thus, circulating cfDNA may be a unique biomarker for OT in patients with COVID-19 among respiratory tract viral infections. Our observation of an inverse correlation between cfDNA levels and the SpO2/FiO2 ratio also supports the potential usefulness of cfDNA as a biomarker for respiratory failure in COVID-19. Another important aspect of our study was that commonly measured bedside biomarkers, such as LDH, d-dimer, and CRP levels, also predicted the requirement for oxygenation in COVID-19 patients. Among the biomarkers examined, LDH showed the highest OR for predicting both OT and MV. Although we did not examine specific isoforms of LDH (i.e., LDH-1–5) in this study43, molecules released from damaged cells, such as LDH and DNA, are likely to be potential biomarker targets for COVID-19.

Our study has several limitations. First, none of the participants had received the current COVID-19 vaccine or effective anti-COVID-19 drugs during recruitment. Some recently developed COVID-19 vaccines have been reported to present systemic immune responses (e.g., fever) as common side effects44,45, and anti-COVID-19 drugs, such as remdesivir and ritonavir-boosted nirmatrelvir, have been shown to ameliorate the severity of COVID-1946,47,48,49. Therefore, COVID-19 vaccination or drug treatment may increase or decrease cfDNA levels in COVID-19 patients. In this regard, the cfDNA levels in the COVID-19 patients examined in our study are unlikely to be affected by medicines targeting SARS-CoV-2. Second, based on the recruitment period of this study, most patients were likely infected with SARS-CoV-2 Alpha (B.1.1.7 and Q lineages)1. It is possible that patients infected with other variants known to cause more severe illness, such as the Delta variant, may present higher levels of circulating cfDNA than the patients recruited in this study. Further studies are needed to clarify whether the virulence of SARS-CoV-2 variants influences the levels of circulating cf-nDNA or cf-mtDNA. Third, it remains unclear whether the comorbidities of COVID-19 patients affected cfDNA levels observed in our study. For example, recent studies have shown that cfDNA levels increase in patients with obesity 7 or COPD 14,15, known comorbidities associated with a higher risk of severe COVID-19 50,51. Therefore, the presence of these comorbidities may have partly contributed to the increased cfDNA levels in patients with severe COVID-19. Finally, due to the low number of deceased cases (3 out of 95)52, we were unable to determine whether cfDNA was a predictive marker of mortality in COVID-19 patients in this study. Nevertheless, our patients’ characteristics were similar to those seen in other reports (e.g., patients with comorbidities such as COPD and DM tended to have greater severity of COVID-19)53,54. Additionally, our ROC curves of both cfDNA types showed a higher AUC in predicting MV than in OT (Figs. 4 and 5), suggesting that cfDNA remains a potential biomarker for predicting critical illness in patients with COVID-19.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated elevated serum levels of cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA in COVID-19 patients who required respiratory intervention, including OT and MV. Both cfDNA levels were inversely correlated with adjusted SpO2 (i.e., SpO2/FiO2 ratio) levels. Circulating cfDNA levels may predict the severity of respiratory condition (i.e., an increase in patients’ oxygen requirement) in the early stages of COVID-19. Further studies are needed to validate cfDNA levels in COVID-19 as predictive markers for assessing disease severity and guiding treatment decisions.

Methods

Study design, study patients, and clinical data collection

This study complied with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Showa University School of Medicine on April 11, 2020 (Study protocol #3176) and Nara Medical University on May 1, 2020 (Study protocol #2651). All patients provided written informed consent before participation. The patients were treated based on the most updated evidence available at that time55,56. MV with endotracheal intubation was performed in patients with worsening respiratory failure. Pressure-controlled ventilation was administered to the patients who received MV. The prone position was used as appropriate in patients with deteriorating respiratory conditions. All patients were followed up with until either discharge or death.

Physiological parameters and comorbid states were collected from patients’ medical records as patient background factors. If no information was available in the medical records, it was collected via telephone. For patient description, we used sex, age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, and laboratory data. Laboratory data, including peripheral blood neutrophils, d-dimer, ferritin, LDH, CRP, BNP, and KL-6, were collected as part of routine clinical care. SpO2 was assessed using standard pulse oximetry. FiO2 was derived either by the FiO2 sensor in the ventilator or estimated through validated formulas considering administered oxygen liters or the manufacturer’s instructions in conventional oxygen support devices.

DNA isolation from serum and PCR

Blood samples were drawn into serum separator tubes within 6 h after admission, followed by centrifugation for 20 min at 2000×g23,24. Subsequently, the serum was separated, aliquoted, and stored at − 80 °C until further processing. DNA was isolated from serum using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (51104; Qiagen), as previously described13,57. DNA levels in the samples were measured by a SYBR Green dye-based quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assay using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences were as follows13,57,58,59: human NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene (mtDNA): forward 5′-ATACCCATGGCCAACCTCCT-3′, reverse 5′-GGGCCTTTGCGTAGTTGTAT-3′; human β-globin (nDNA): forward 5′-GTGCACCTGACTCCTGAGGAGA-3′, reverse 5′-CCTTGATACCAACCTGCCCAG-3′; double-stranded DNA (gBlocks®) with complementary DNA sequences for human mtDNA and nDNA was obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies. The thermal profile was determined as previously described13,57.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as medians and interquartile ranges, whereas nominal variables are expressed as frequencies (%). Differences in continuous variables were analyzed using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test or Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate. Differences in categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson χ2 tests. To assess whether cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA could predict the patients’ probability of requiring oxygenation and intubation, we performed ROC analysis and identified the sensitivity, specificity, and cutoff points for cf-nDNA and cf-mtDNA. The cutoff point was determined to maximize the sensitivity and specificity in accordance with the Youden index. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the clinical factors associated with OT or MV, including cf-nDNA or cf-mtDNA. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to examine the association between serum cf-nDNA or cf-mtDNA levels and clinical parameters. Correlations between cfDNA levels and clinical biomarkers were determined using Spearman’s correlation. All analyses were performed using JMP, version 16 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, U.S.A). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for all analyses.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study complied with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Showa University School of Medicine on April 11, 2020 (Study protocol #3176) and Nara Medical University on May 1, 2020 (Study protocol #2651). All patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Hu, B., Guo, H., Zhou, P. & Shi, Z. L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7 (2021).

Kananen, L. et al. Circulating cell-free DNA level predicts all-cause mortality independent of other predictors in the Health 2000 survey. Sci. Rep. 10, 13809. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70526-9 (2020).

Harrington, J. S. et al. Circulating mitochondrial DNA as predictor of mortality in critically ill patients: A systematic review of clinical studies. Chest 156, 1120–1136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.07.014 (2019).

Nakahira, K., Hisata, S. & Choi, A. M. The roles of mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns in diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 23, 1329–1350. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2015.6407 (2015).

Stortz, J. A. et al. Cell-free nuclear, but not mitochondrial, DNA concentrations correlate with the early host inflammatory response after severe trauma. Sci. Rep. 9, 13648. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50044-z (2019).

Al-Kafaji, G., Jahrami, H. A., Alwehaidah, M. S., Alshammari, Y. & Husni, M. Mitochondrial DNA copy number in autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1196035. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1196035 (2023).

Camuzi Zovico, P. V. et al. Cell-free DNA as an obesity biomarker. Physiol. Res. 69, 515–520. https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.934242 (2020).

Cossarizza, A. et al. Increased plasma levels of extracellular mitochondrial DNA during HIV infection: A new role for mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns during inflammation. Mitochondrion 11, 750–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2011.06.005 (2011).

Johnston, C. D. et al. Plasma cell-free mitochondrial DNA as a marker of geriatric syndromes in older adults with HIV. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 90, 456–462. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002993 (2022).

Johnston, C. D. et al. Plasma extracellular vesicles and cell-free mitochondrial DNA are associated with cognitive dysfunction in treated older adults with HIV. J. Neurovirol. 29, 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-023-01122-6 (2023).

Bulgakova, O. et al. The level of free-circulating mtDNA in patients with radon-induced lung cancer. Environ. Res. 207, 112215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.112215 (2022).

Ryu, C. et al. Extracellular mitochondrial DNA is generated by fibroblasts and predicts death in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 196, 1571–1581. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201612-2480OC (2017).

Nakahira, K. et al. Circulating mitochondrial DNA in patients in the ICU as a marker of mortality: Derivation and validation. PLoS Med. 10, e1001577. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001577 (2013) (discussion e1001577).

Ware, S. A. et al. Cell-free DNA levels associate with COPD exacerbations and mortality. Respir. Res. 25, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02658-1 (2024).

Zhang, W. Z. et al. Association of plasma mitochondrial DNA with COPD severity and progression in the SPIROMICS cohort. Respir Res 22, 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-021-01707-x (2021).

Liaw, P. C., Ito, T., Iba, T., Thachil, J. & Zeerleder, S. DAMP and DIC: The role of extracellular DNA and DNA-binding proteins in the pathogenesis of DIC. Blood Rev. 30, 257–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2015.12.004 (2016).

Gong, T., Liu, L., Jiang, W. & Zhou, R. DAMP-sensing receptors in sterile inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0215-7 (2020).

Marchi, S., Guilbaud, E., Tait, S. W. G., Yamazaki, T. & Galluzzi, L. Mitochondrial control of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00760-x (2022).

Scozzi, D. et al. Circulating mitochondrial DNA is an early indicator of severe illness and mortality from COVID-19. JCI Insight https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.143299 (2021).

Andargie, T. E. et al. Cell-free DNA maps COVID-19 tissue injury and risk of death and can cause tissue injury. JCI Insight https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.147610 (2021).

Hammad, R. et al. Circulating cell-free DNA, peripheral lymphocyte subsets alterations and neutrophil lymphocyte ratio in assessment of COVID-19 severity. Innate Immun. 27, 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753425921995577 (2021).

Valdes-Aguayo, J. J. et al. Peripheral blood mitochondrial dna levels were modulated by SARS-CoV-2 infection severity and its lessening was associated with mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 754708. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.754708 (2021).

Miyata, Y. et al. Serum cystatin C and CRP are early predictive biomarkers for emergence of hypoxia in COVID-19. Am. J. Med. Sci. 364, 706–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2022.06.027 (2022).

Fukuda, Y. et al. Serum IL-28A/IFN-lambda2 is linked to disease severity of COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 12, 5458. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09544-8 (2022).

Fukuda, Y. et al. Utility of SpO2/FiO2 ratio for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure with bilateral opacities in the ICU. PLoS ONE 16, e0245927. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245927 (2021).

Kim, J. H. et al. ROX index and SpO2/FiO2 ratio for predicting high-flow nasal cannula failure in hypoxemic COVID-19 patients: A multicenter retrospective study. PLoS ONE 17, e0268431. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268431 (2022).

Spinner, C. D. et al. Effect of remdesivir vs standard care on clinical status at 11 days in patients with moderate COVID-19: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 324, 1048–1057. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.16349 (2020).

Attaway, A. H., Scheraga, R. G., Bhimraj, A., Biehl, M. & Hatipoglu, U. Severe covid-19 pneumonia: Pathogenesis and clinical management. BMJ 372, n436. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n436 (2021).

Iwamura, C. et al. Elevated Myl9 reflects the Myl9-containing microthrombi in SARS-CoV-2-induced lung exudative vasculitis and predicts COVID-19 severity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2203437119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2203437119 (2022).

Szarpak, L. et al. Lactate dehydrogenase level as a COVID-19 severity marker. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 45, 638–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.11.025 (2021).

Martha, J. W., Wibowo, A. & Pranata, R. Prognostic value of elevated lactate dehydrogenase in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad. Med. J. 98, 422–427. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139542 (2022).

Yao, Y. et al. D-dimer as a biomarker for disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients: A case control study. J. Intensive Care 8, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-020-00466-z (2020).

Yu, H. H., Qin, C., Chen, M., Wang, W. & Tian, D. S. D-dimer level is associated with the severity of COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 195, 219–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.07.047 (2020).

Alroomi, M. et al. Ferritin level: A predictor of severity and mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 9, 1648–1655. https://doi.org/10.1002/iid3.517 (2021).

Stawski, R., Nowak, D. & Perdas, E. Cell-free DNA: Potential application in COVID-19 diagnostics and management. Viruses https://doi.org/10.3390/v14020321 (2022).

Bronkhorst, A. J., Ungerer, V. & Holdenrieder, S. The emerging role of cell-free DNA as a molecular marker for cancer management. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 17, 100087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bdq.2019.100087 (2019).

Veras, F. P. et al. SARS-CoV-2-triggered neutrophil extracellular traps mediate COVID-19 pathology. J. Exp. Med. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20201129 (2020).

Zuo, Y. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.138999 (2020).

Zhan, H. et al. Diagnostic value of d-dimer in COVID-19: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 27, 10760296211010976. https://doi.org/10.1177/10760296211010976 (2021).

Melchinger, H., Jain, K., Tyagi, T. & Hwa, J. Role of platelet mitochondria: Life in a nucleus-free zone. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 6, 153. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2019.00153 (2019).

Gremmel, T., Frelinger, A. L. 3rd. & Michelson, A. D. Platelet physiology. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 42, 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1564835 (2016).

Boudreau, L. H. et al. Platelets release mitochondria serving as substrate for bactericidal group IIA-secreted phospholipase A2 to promote inflammation. Blood 124, 2173–2183. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-05-573543 (2014).

Farhana, A. & Lappin, S. L. StatPearls (2022).

Beatty, A. L. et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA . Open 4, e2140364. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364 (2021).

Menni, C. et al. Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK: A prospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 939–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00224-3 (2021).

Update to living systematic review on drug treatments for covid-19. BMJ 378, o1717, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o1717 (2022).

Murakami, N. et al. Therapeutic advances in COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-022-00642-4 (2022).

Hammond, J. et al. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 1397–1408. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2118542 (2022).

Beigel, J. H. et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—final report. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1813–1826. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2007764 (2020).

Mohammad, S. et al. Obesity and COVID-19: What makes obese host so vulnerable?. Immun. Ageing 18, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12979-020-00212-x (2021).

Gerayeli, F. V. et al. COPD and the risk of poor outcomes in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 33, 100789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100789 (2021).

Onozuka, D. et al. Reduced mortality during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan, 2020: A two-stage interrupted time-series design. Int. J. Epidemiol. 51, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab216 (2022).

Dessie, Z. G. & Zewotir, T. Mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 21, 855. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06536-3 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Comorbidities and the risk of severe or fatal outcomes associated with coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 99, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.029 (2020).

Wiersinga, W. J., Rhodes, A., Cheng, A. C., Peacock, S. J. & Prescott, H. C. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A review. JAMA 324, 782–793. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.12839 (2020).

Agarwal, A. et al. A living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19. BMJ 370, m3379. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3379 (2020).

Zhang, W. Z. et al. Association of urine mitochondrial DNA with clinical measures of COPD in the SPIROMICS cohort. JCI Insight https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.133984 (2020).

Moreira, V. G., Prieto, B., Rodriguez, J. S. & Alvarez, F. V. Usefulness of cell-free plasma DNA, procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as markers of infection in febrile patients. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 47, 253–258. https://doi.org/10.1258/acb.2010.009173 (2010).

Yang, Q. et al. Evaluation of suitable control genes for quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of maternal plasma cell-free DNA. Mol. Med. Rep. 12, 7728–7734. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2015.4334 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Akiyo Nakano for technical support and Megumi Matsuda for collecting blood samples. The authors also thank Editage for reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH KL2-TR-0002385 (K.N.), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI 20K09293 (K. N.), 23K08465 (K.N.), 20K07073 (M.Y.), Nara Prefecture Health Promotion Center R02-2 (K.N.), Nara Medical University Grant-in-Aid for Collaborative Research Projects (K.N.), and a research grant from the Kobayashi Foundation (K.N.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft. K.W.: investigation, methodology, data curation, writing–review and editing. Y.F., S.O., T.H.: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing. K.A.: formal analysis, investigation, writing—review, and editing. Y.N.: investigation, writing—review and editing. R.N., J.Z., Y.S., K.K., K-P.C.: methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing. Y.K.: investigation, writing—review, and editing. H.Y., H.S.: resources, investigation, writing—review and editing. M.Y.: investigation, resources. funding acquisition. writing—review, and editing. K.N.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, funding acquisition. writing—original draft. supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, A., Wakayama, K., Fukuda, Y. et al. Increased levels of circulating cell-free DNA in COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure. Sci Rep 14, 17399 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68433-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68433-4

This article is cited by

-

Cytosolic nucleic acid sensing as driver of critical illness: mechanisms and advances in therapy

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2025)

-

A feedback loop between DNA damage, genomic instability, and cytoplasmic DNA sensing contributes to cytokine production in COVID-19

Archives of Virology (2025)