Abstract

We aimed to assess the weight loss trend following Roux en Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB), One Anastomosis Gastric Bypass (OAGB), and Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG), utilizing a change-point analysis. A retrospective cohort study was conducted on 8640 patients, from 2009 to 2023. The follow-up period extended to 7 years, with a median follow-up of 3 years (interquartile range: 1.4–5). Following metabolic bariatric surgery, four weight loss phases (three change points) were observed. The primary, secondary, and tertiary phases, transitioned at 12.64–13.73 days, 4.2–4.8 months, and 11.3–13.1 months post-operation, respectively, varying based on the type of procedure. The weight loss rate decreased following each phase and plateaued after the tertiary phase. The nadir weight was achieved 11.3–13.1 months post-procedure. There was no significant difference in the %TWL between males and females, however, males achieved their nadir weight significantly earlier. Half of the maximum %TWL was achieved within the first 5 months, with the greatest reduction rate in the first 2 weeks. Our findings inform healthcare providers of the optimal timing for maximum weight loss following each surgical method and underscore the importance of close patient monitoring in the early postoperative period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is recognized as a major public health crisis, affecting over a billion individuals globally. Metabolic bariatric surgery (MBS) has emerged as a life-changing solution for individuals with severe obesity experiencing significant health-related problems, who have been unsuccessful in achieving sustained weight loss through non-surgical methods. It not only leads to substantial reductions in body weight but also improves associated health complications, thus enhancing the quality of life for numerous patients struggling with obesity1,2,3,4. While these surgeries have been shown to be effective in achieving weight loss, the weight loss trends vary over time. Understanding the weight loss trends following these procedures holds significant importance in clinical practice.

Patients experience a gradual weight loss following MBS until reaching their lowest weight (nadir weight). Nevertheless, it has been observed that the weight loss trend changes and many patients face recurrent weight gain at some point. A 5-year follow-up shows 50.2% gaining 15% or greater of the nadir weight, and 86.5% gaining 10% or greater of the maximum weight loss following surgery5,6. The timeframe for reaching nadir weight varies across studies, with most reporting it within 12 to 24 months following surgery, while recurrent weight gain has typically been observed between 1 to 5 years post-surgery in the majority of studies. The highest rate of recurrent weight gain occurs during the first year following nadir weight, but data suggests that this trend continues throughout follow-ups5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Understanding the time point patients achieve their highest weight loss rates and nadir weight following surgery is crucial for assessing surgical efficacy and identifying suboptimal initial clinical response or recurrent weight gain.

This large-scale study aims to assess the weight loss trend following three common MBS procedures including Roux en Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB), One Anastomosis Gastric Bypass (OAGB), and Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG), over a 7-year follow-up period. Utilizing a change-point analysis, we seek to identify the specific time points at which the weight loss trend changes. Understanding the weight changes following these procedures may improve patient outcomes by informing healthcare providers of the optimal timing for maximum weight loss following each surgical method. This knowledge allows them to closely monitor patients' progress during this critical period and adjust weight management strategies accordingly.

Materials and methods

A single-center retrospective cohort study was conducted in a referral bariatric center from 2009 to 2023. The study population consisted of adult individuals aged ≥ 18 with morbid obesity defined as Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 35, who underwent one of the following types of MBS: OAGB, RYGB, or SG with at least one follow-up visit after the procedure. The exclusion criteria were defined as those who underwent secondary MBS procedures, pregnancy throughout the follow-up period, major complications such as leakage or hemorrhage, and prolonged ICU admission.

Data on demographic information including age and gender, anthropometric measurements encompassing height, weight, and BMI, co-morbidities including Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), Hypertension, and Hypothyroidism, operative information, and postoperative follow-ups were obtained from the Iran National Obesity Surgery Database (INOSD). More information regarding the INOSD is available elsewhere12,13.

All patients were evaluated by a multidisciplinary team prior to MBS based on the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) guidelines. All procedures were performed by a single experienced MBS surgeon. The selection of the type of surgical procedure was based on the surgeon’s judgment and each patient's characteristics, including initial BMI, comorbidities, dietary habits, endoscopic findings, and patient preferences. The perioperative and follow-up protocols were similar for all MBS procedures. Patients were followed up at 10 days, 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, and subsequently annually after operation. However, follow-up visits did not always occur precisely at predetermined intervals. To ensure a continuous timeline and enable a more precise assessment of weight changes and weight loss trends throughout the entire follow-up period, data was entered by the date of each patient visit, rather than being limited to the predetermined follow-up time points. This approach allowed for a more accurate analysis of weight loss trends, as it accounted for the exact timing of patient visits and provided a more comprehensive understanding of the weight loss trends following MBS.

Weight loss outcomes were measured by percentage total weight loss (%TWL) calculated as:

Suboptimal initial response was defined as total body weight loss of less than 20%. Late postoperative deterioration was defined as recurrent weight gain of more than 30% of the initial surgical weight loss14.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of continuous variables was initially characterized using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. Variables that met the normality assumption were described using the mean and standard deviation, while the median and interquartile range were used for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. The distributions of variables across different surgical types were compared using a one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and a chi-squared test for categorical variables.

The factors influencing the TWL were investigated using a generalized linear regression model via a generalized estimating equation (GEE). Both univariate and multivariate models were constructed.

To detect change points in the weight reduction trend, we utilized a Bayesian inference method known as Multiple Change Points (MCP) between linear segments. This approach uses random initial points to divide the overall trend into segments, aiming to minimize the ratio of between-segment variation to within-segment variation. To ascertain the optimal number of segmentations, we fitted a linear model with a single segmentation and compared it with models containing 2, 3, and 4 segmentations. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) were employed for model comparison, assisting in the selection of the most suitable number of thresholds.

All statistical analyses and data visualizations were conducted using R statistical software (version 4.2.2, https://www.R-project.org). A significance level of 0.05 was applied to all analyses.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committees of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC.1402.770). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and informed written consent was obtained from all participants for the utilization of their data on the Iran National Obesity Surgery Database for future research purposes.

Results

Baseline characteristics and factors associated with weight loss

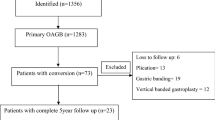

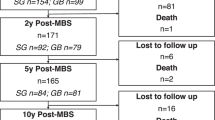

Of a total of 9582 individuals undergoing OAGB, SG, or RYGB surgery in our center from 2009 to 2023, 152 individuals under the age of 18, 238 individuals undergoing secondary surgery, 488 individuals with a BMI less than 35 kg/m2, 276 pregnant women, and 46 patients with major complications were excluded from the study. 8640 cases were included in the final analysis, with 54.5% undergoing OAGB, 17.5% undergoing RYGB, and 28% undergoing SG (Fig. 1).

Table 1 presents the characteristics of participants. The mean age of the study population was 40 years (SD: 11) and the majority were female constituting 78% of the participants. The mean pre-operative BMI was 44.9 kg/m2 (SD: 6.0). The median follow-up period was 3 years (IQR: 1.4–5), yet it varied among different types of surgery with RYGB having the longest follow-up [5 years (IQR: 4–9)] and SG the shortest [2 years (IQR: 1.1–3.2)]. The number of participants was 6,794 after one year and 5,190 after two years (Table 1).

In both univariate and multivariate regression analyses using the GEE approach, the %TWL was significantly higher in patients who underwent OAGB (p-value < 0.001) and significantly lower in those who underwent RYGB (p-value < 0.001), in comparison to SG. T2DM and older age were associated with a lower %TWL, while higher baseline BMI was associated with a higher %TWL. However, there was no significant difference in %TWL between males and females (Table 2).

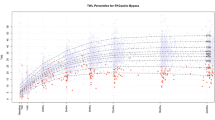

Weight loss trends

Following MBS, four weight loss phases were observed: the primary weight loss phase, the secondary weight loss phase, the tertiary weight loss phase, and the plateau phase. Following the initial three phases, a decrease in the rate of weight loss was observed, leading to the onset of a subsequent phase characterized by a sustained reduction in weight loss rate, until the weight loss rate stabilized, and the plateau phase was observed (Fig. 2). The secondary, tertiary, and plateau phases were reached at 12.6–13.7 days, 4.2–4.8 months, and 11.3–13.1 months post-operation, respectively.

RYGB was the first to reach the secondary weight loss phase (in 12.6 days), while SG was the last (in 13.7 days) (Table 3). The weight loss phases transitioned earlier following RYGB with the nadir weight being reached at 11.3 months. The tertiary and plateau phases were observed later following OAGB compared to RYGB and SG (in 4.8 vs 4.2 and 4.7 months and 13.1 vs. 11.3 and 12.7 months). OAGB was the last procedure to reach the nadir weight after 13.1 months. The overlapping confidence intervals suggest that the time to reach the secondary weight loss phase and plateau phase are comparable between the three types of procedures. However, the time to reach the tertiary weight loss phase occurred significantly earlier following RYGB.

Remarkably, the tertiary weight loss phase and plateau phase occurred significantly earlier in males compared to females in all three types of MBS procedures (Fig. 3). The non-overlapping confidence intervals suggest that males achieved the nadir weight significantly earlier (Table 3).

During the plateau phase, a notable shift was observed in the weight loss trend, indicating a tendency towards recurrent weight gain. Patients who underwent RYGB and OAGB exhibited a daily decrease of 0.003 in the %TWL, while a daily decrease of 0.006 was observed in those who underwent SG (Table 3).

Weight loss outcomes

OAGB had better weight loss outcomes at the time of reaching the plateau phase and achieved TWL of 36.9% in 13.1 months after surgery, while RYGB and SG achieved 31.7% and 34.3% TWL in 11.3 and 12.7 months respectively. The initial slope of weight loss in the primary weight loss phase was higher in RYGB (0.64) compared to OAGB (0.61) and SG (0.63), according to %TWL measures, meaning that a TWL of 6.4% was achieved 10 days after RYGB surgery compared to 6.1% and 6.3% following OAGB and SG consecutively (Table 3). During the primary weight loss phase RYGB, OAGB, and SG achieved a %TWL of 8.1%, 8.3%, and 8.7% respectively, within 12.6, 13.7, and 13.7 days, indicating that over 20% of the maximum %TWL was attained within the first 2 weeks after all three MBS procedures. At the end of the secondary weight loss phase, a %TWL of 23.1%, 26.9%, and 27.0% were attained following RYGB, OAGB, and SG respectively, in 4.2, 4.8, and 4.7 months. Over half of the maximum %TWL [54% (18.5/34.3) in SG; 51% (18.8/36.9) in OAGB; 50.5% (16/31.7) in RYGB] was achieved within the initial 5 months post-MBS.

After a 5-year follow-up period following MBS, the total rate of late postoperative deterioration (recurrent weight gain) was 14.4%. Specifically, 17.5% of patients who underwent SG, 16.7% of those who underwent RYGB, and 11.6% of those who underwent OAGB experienced recurrent weight gain. The rate of recurrent weight gain was significantly lower in patients who underwent OAGB (p-value < 0.001) (Table 1).

Discussion

The present study provides valuable insights into weight loss patterns following three common MBS procedures including RYGB, OAGB, and SG. The weight loss trend stabilizes approximately a year post-operation (11.3–13.1 months), whereby maximum weight loss is achieved and the individuals reach their nadir weight. The main weight reduction occurs primarily within the first 5 months, with the greatest reduction rate in the first 2 weeks, highlighting the critical importance of early and intensive patient monitoring during the initial postoperative period. Early identification of suboptimal clinical responders is crucial for timely intervention and optimization of therapeutic outcomes.

Numerous studies have previously investigated the timeline for the achievement of nadir weight following MBS, with some reporting it 12 months post-operation8,15,16,17 and others suggesting it occurs within 18–24 months9,17,18,19. However, these estimates may be limited by the fixed postoperative follow-up periods, which were typically conducted at six-month intervals. To overcome this limitation, our study utilized a continuous timeline approach with data entry by the exact date, allowing for a more precise estimated range of 11.3 to 13.1 months for reaching the nadir weight, depending on the type of surgery.

While this study is observational and lacks randomization, it offers valuable insights for readers regarding different surgical procedures. Establishing a causal relationship is not possible; however, the comparison between different procedures provides important clues. It is imperative to interpret these findings with caution. In this context, the OAGB procedure appears to have a longer timeline for achieving the nadir weight, ensuring sustained weight loss over an extended period. Notably, patients who underwent OAGB achieved the highest %TWL at 36.9%, surpassing the effectiveness of both RYGB (31.7%) and SG (34.3%). Moreover, the %TWL was significantly higher in OAGB patients and significantly lower in those who underwent RYGB, compared to SG. Consistent with our findings, a multicenter study including 9617 patients from India found better weight reduction outcomes in OAGB compared to RYGB and SG20. Additionally, a systematic review of 25 randomized control trials (RCTs) comparing OAGB or SG to RYGB showed that OAGB had superior weight loss outcomes compared to RYGB, and RYGB had superior outcomes compared to SG21. However, SG showed better weight reduction outcomes in our findings compared to RYGB.

Approximately 15–35% of patients experience suboptimal initial clinical response following MBS. This outcome is often associated with various factors such as mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, alcohol and substance abuse, attentional impulsiveness, personality disorder, and low self-esteem. In addition, eating behaviors such as increased consumption of sweets, emotional eating, binge eating, loss of control and disinhibition during eating, and not following dietary and exercise instructions have also been linked to a suboptimal initial clinical response. Lack of adherence to regular and long-term follow-up, low socio-economic status, and genetics are further contributory factors22,23. Therefore, it is essential to adopt a multi-disciplinary approach, involving comprehensive assessments to effectively prevent and manage inadequate weight loss. Behavioral therapy and lifestyle counseling, dietitian counseling and structured dietary intervention, support group programs, and pharmacological agents such as phentermine and liraglutide have demonstrated efficacy in addressing this issue24,25,26,27. The current study presents a timeline of anticipated weight changes following MBS, highlighting key points for effective intervention. Notably, over half of the maximum TWL (51% in OAGB, 50.5% in RYGB, and 54% in SG) was achieved within the initial 5 months post-surgery, underscoring the importance of close observation with shorter follow-up intervals during this critical period. Timely detection of individuals with suboptimal initial clinical response (demonstrated either by total body weight of less than 20% or by inadequate improvement in an obesity complication that was a significant indication for surgery)14 and an understanding of the underlying factors contributing to inadequate weight loss can result in more efficacious intervention strategies, ultimately decreasing suboptimal initial clinical responses. This study emphasizes the importance of closely monitoring patients in the initial postoperative period and implementing early psychological and dietary interventions to enhance weight loss outcomes.

Recurrent weight gain after MBS is a major concern that significantly impacts the long-term success of the procedure. Various factors contribute to recurrent weight gain, such as dysregulated or maladaptive eating, noncompliance with dietary recommendations, sedentary lifestyle, hormonal changes, and psychological issues. Recurrent weight gain has a negative impact on the quality of life and obesity-related comorbidities7,26,28. The overall rate of recurrent weight gain was 14.4% in the present study. Notably, individuals who underwent RYGB and SG had significantly higher rates of recurrent weight gain (16.7% and 17.5%) compared to those who underwent OAGB (11.6%; p-value < 0.001). Consistent with prior research, OAGB demonstrated superior outcomes in terms of recurrent weight gain7,20,29. Therefore, OAGB might be the preferable choice for patients prone to weight gain. For individuals undergoing RYGB and SG, close monitoring may be required for early detection of recurrent weight gain and for devising a personalized management plan, which may include dietary and lifestyle changes, psychological support, and revisional surgery if required. Overall, addressing recurrent weight gain after MBS is crucial to optimize patient outcomes and ensure that patients receive the full benefits of the procedure and maintain optimal health outcomes.

In accordance with prior studies, our findings revealed a negative correlation between age and T2DM with weight loss30,31,32,33. Additionally, a higher initial BMI was associated with a greater %TWL34,35. The relationship between gender and weight loss has been inconsistently reported in previous studies, with some indicating female gender as an unfavorable factor for weight loss and others suggesting the opposite30,31. Our study did not reveal a significant difference in the %TWL between males and females. However, males achieved their nadir weight significantly earlier than females. Similarly, a study by Alfadda et al.36 Also reported earlier achievement of the nadir weight in males.

It was noted that the initial BMI tended to be slightly higher in the OAGB surgery group. This finding may be attributed to the selection of this surgical procedure for patients with higher BMIs, considering its favorable outcomes in terms of weight loss21,37,38. Additionally, a higher baseline prevalence of comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes and hypertension, was observed in the OAGB group. This observation can potentially be linked to the selection of this surgical procedure for patients with such comorbidities, as OAGB has been noted for its better comorbidity resolution rates39,40,41.

The present study is notable for its large scale and prolonged duration of follow-up. With the relatively recent rise of OAGB as a popular surgical approach, long-term follow-up data on this procedure is limited. Despite this, our study presents a substantial sample size of OAGB cases, with an acceptable length of follow-up, contributing valuable insights to the existing knowledge regarding the outcomes of OAGB. All surgical procedures and postoperative care were conducted solely by a single surgical team under the supervision of one surgeon, thereby ensuring uniformity in the practices employed. The perioperative and follow-up protocols were similar for all MBS procedures to minimize variability in outcomes due to differences in clinical practices. Additionally, our data entry process ensured a cohesive timeline and permitted a more meticulous evaluation of weight changes throughout the follow-up period, which enabled us to conduct a more precise analysis of weight loss trends.

However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations, including variance in the duration of follow-up periods among different MBS procedures (2 years post-SG to 5 years post-RYGB). Moreover, a decrease in the number of patients was observed in our study as the duration of follow-up extended (Fig. 1). The number of participants decreased to 6,794 one year after operation and to 5,190 two years after (Table 1). RYGB had longer follow-up durations and a higher proportion of its participants had long follow-up periods, compared to other procedures, likely due to its status as the earliest MBS procedure performed at our center. As a procedure's history extends, more patients undergo follow-ups annually, contributing to increased long-term follow-ups. Conversely, in more recently performed procedures, like OAGB, fewer patients reach longer follow-ups, resulting in comparatively shorter follow-up durations. Given that SG does not require gastrointestinal anastomosis or a bypass, it is anticipated to result in fewer nutritional deficiencies and complications42,43. Consequently, for patients having difficulties with adhering to follow-up visits, such as those from distant provinces, foreign countries, or with other constraints, SG has been the preferred choice at our center. This selection may potentially contribute to the observed lower number of participants in longer follow-ups and shorter follow-up durations associated with this procedure. Nevertheless, our results remained consistent despite these potential confounders. Our study period incorporated the COVID-19 pandemic era, which could potentially introduce confounding factors. Nonetheless, a recent investigation conducted at our center, utilizing data from the INOSD—the database used in our study—compared individuals who underwent MBS during the COVID-19 pandemic with a control group that completed their 6-month follow-up before the pandemic. The results of this study demonstrated no significant difference between the groups concerning weight reduction44. Consequently, we decided against excluding the COVID-19 period from our study's analysis. Furthermore, the retrospective design of our study is another limitation. This study was conducted at a single medical center, which could limit the applicability of the results to other healthcare settings with different surgical techniques, or postoperative management protocols. As a non-randomized, observational study, we cannot establish a causal relationship between the variables under investigation. Further multicenter prospective studies with a randomized controlled trial design may be required to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

The weight loss achieved through MBS tends to plateau around 11.3 to 13.1 months post-procedure, with patients undergoing RYGB reaching their nadir weight earlier in 11.3 months, and those undergoing OAGB taking slightly longer to reach their nadir weight in 13.1 months. The %TWL did not differ between males and females, however, males achieved their nadir weight significantly earlier than females. Furthermore, OAGB demonstrated superior outcomes in terms of weight loss and recurrent weight gain compared to RYGB and SG. The main weight reduction was observed primarily within the first 5 months, with the greatest reduction rate in the first 2 weeks, underscoring the importance of close patient monitoring in the early postoperative period. Our study's findings on weight loss change points after MBS provide valuable insights for healthcare providers to better evaluate patients’ weight loss outcomes at specific time points post-procedure. This knowledge allows them to closely monitor patients' progress during this critical period and adjust weight management strategies accordingly. Early implementation of psychological and dietary interventions, personalized lifestyle changes, and regular follow-up appointments, particularly within the first 5 months postoperatively, enables healthcare providers to optimize weight loss outcomes and minimize the risk of suboptimal clinical responses in patients undergoing MBS.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jabbour, G. & Salman, A. Bariatric surgery in adults with obesity: The impact on performance, metabolism, and health indices. Obes Surg 31, 1767–1789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-05182-z (2021).

Lo, T. & Tavakkoli, A. Bariatric surgery and its role in obesity pandemic. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 12, 51–56 (2019).

Nguyen, N. T. & Varela, J. E. Bariatric surgery for obesity and metabolic disorders: State of the art. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2016.170 (2017).

Wolfe, B. M., Kvach, E. & Eckel, R. H. Treatment of obesity: Weight loss and bariatric surgery. Circ. Res. 118, 1844–1855. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.116.307591 (2016).

King, W. C., Hinerman, A. S., Belle, S. H., Wahed, A. S. & Courcoulas, A. P. Comparison of the performance of common measures of weight regain after bariatric surgery for association with clinical outcomes. JAMA 320, 1560–1569. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14433 (2018).

Maciejewski, M. L. et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 151, 1046–1055. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2317 (2016).

Noria, S. F., Shelby, R. D., Atkins, K. D., Nguyen, N. T. & Gadde, K. M. Weight regain after bariatric surgery: Scope of the problem, causes, prevention, and treatment. Curr. Diab. Rep. 23, 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-023-01498-z (2023).

Peterli, R. et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: The SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 319, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.20897 (2018).

Santos, A. L. et al. Weight regain and the metabolic profile of women in the postoperative period of bariatric surgery: A multivariate analysis. ABCD Arquivos Brasileiros de Cirurgia Digestiva São Paulo 36, e1755 (2023).

Tolvanen, L., Christenson, A., Surkan, P. J. & Lagerros, Y. T. Patients’ experiences of weight regain after bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 32, 1498–1507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-05908-1 (2022).

Yarigholi, F. et al. Predictors of weight regain and insufficient weight loss according to different definitions after sleeve gastrectomy: A retrospective analytical study. Obes. Surg. 32, 4040–4046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06322-3 (2022).

Kabir, A., Pazouki, A. & Hajian, M. Iran obesity and metabolic surgery (IOMS) cohort study: Rationale and design. Indian J. Surg. 1–9 (2021).

Kermansaravi, M. et al. The first web-based Iranian national obesity and metabolic surgery database (INOSD). Obes. Surg. 32, 2083–2086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06014-y (2022).

Salminen, P. et al. IFSO consensus on definitions and clinical practice guidelines for obesity management—An international Delphi Study. Obes. Surg. 34, 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06913-8 (2024).

Grönroos, S. et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss and quality of life at 7 years in patients with morbid obesity: The SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 156, 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5666 (2021).

Schauer, P. R. et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 641–651. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1600869 (2017).

Sjöström, L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial—A prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J. Intern. Med. 273, 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12012 (2013).

Lemanu, D. P. et al. Five-year results after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A prospective study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 11, 518–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2014.08.019 (2015).

Magro, D. O. et al. Long-term weight regain after gastric bypass: A 5-year prospective study. Obes. Surg. 18, 648–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9265-1 (2008).

Baig, S. J., Priya, P., Mahawar, K. K. & Shah, S. Weight regain after bariatric surgery—A multicentre study of 9617 patients from Indian bariatric surgery outcome reporting group. Obes. Surg. 29, 1583–1592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03734-6 (2019).

Uhe, I. et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or one-anastomosis gastric bypass? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Obesity (Silver Spring) 30, 614–627. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23338 (2022).

Cadena-Obando, D. et al. Are there really any predictive factors for a successful weight loss after bariatric surgery?. BMC Endocr. Disord. 20, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-0499-4 (2020).

Kim, E. Y. Definition Mechanisms and predictors of weight loss failure after bariatric surgery. J. Metab. Bariatr. Surg. 11, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.17476/jmbs.2022.11.2.39 (2022).

Amiki, M. et al. Revisional bariatric surgery for insufficient weight loss and gastroesophageal reflux disease: Our 12-year experience. Obes. Surg. 30, 1671–1678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04374-6 (2020).

Andreu, A. et al. Bariatric support groups predicts long-term weight loss. Obes. Surg. 30, 2118–2123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04434-2 (2020).

El Ansari, W. & Elhag, W. Weight regain and insufficient weight loss after bariatric surgery: Definitions, prevalence, mechanisms, predictors, prevention and management strategies, and knowledge gaps—A scoping review. Obes. Surg. 31, 1755–1766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-05160-5 (2021).

Nijamkin, M. P. et al. Comprehensive nutrition and lifestyle education improves weight loss and physical activity in Hispanic Americans following gastric bypass surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 112, 382–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.10.023 (2012).

Jirapinyo, P., Abu Dayyeh, B. K. & Thompson, C. C. Weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has a large negative impact on the Bariatric Quality of Life Index. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 4, e000153. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgast-2017-000153 (2017).

Hatami, M., Pazouki, A., Hosseini-Baharanchi, F. S. & Kabir, A. Bariatric surgeries, from weight loss to weight regain: A retrospective five-years cohort study. Obes. Facts 16, 540–547. https://doi.org/10.1159/000533586 (2023).

Melton, G. B., Steele, K. E., Schweitzer, M. A., Lidor, A. O. & Magnuson, T. H. Suboptimal weight loss after gastric bypass surgery: Correlation of demographics, comorbidities, and insurance status with outcomes. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 12, 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0427-1 (2008).

Park, J. Y. Weight loss prediction after metabolic and bariatric surgery. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 32, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes23008 (2023).

Rebelos, E., Moriconi, D., Honka, M. J., Anselmino, M. & Nannipieri, M. Decreased weight loss following bariatric surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes. Obes. Surg. 33, 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06350-z (2023).

Saux, P. et al. Development and validation of an interpretable machine learning-based calculator for predicting 5-year weight trajectories after bariatric surgery: A multinational retrospective cohort SOPHIA study. Lancet Digit. Health 5, e692–e702. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2589-7500(23)00135-8 (2023).

Grover, B. T. et al. Defining weight loss after bariatric surgery: A call for standardization. Obes. Surg. 29, 3493–3499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04022-z (2019).

Ochner, C. N., Jochner, M. C., Caruso, E. A., Teixeira, J. & Xavier Pi-Sunyer, F. Effect of preoperative body mass index on weight loss after obesity surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 9, 423–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2012.12.009 (2013).

Alfadda, A. A. et al. Long-term weight outcomes after bariatric surgery: A single center Saudi Arabian cohort experience. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214922 (2021).

Barzin, M., et al. Does one-anastomosis gastric bypass provide better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy in patients with BMI greater than 50? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 109, 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1097/js9.0000000000000203 (2023)

Castro, M. J. et al. Long-term weight loss results, remission of comorbidities and nutritional deficiencies of sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-En-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) on type 2 diabetic (T2D) patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207644 (2020).

Bhandari, M., Nautiyal, H. K., Kosta, S., Mathur, W. & Fobi, M. Comparison of one-anastomosis gastric bypass and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for treatment of obesity: A 5-year study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 15, 2038–2044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2019.05.025 (2019).

Ding, Z. et al. Comparison of single-anastomosis gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy on type 2 diabetes mellitus remission for obese patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asian J. Surg. 46, 4152–4160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2023.03.062 (2023).

Vrakopoulou, G. Z., Theodoropoulos, C., Kalles, V., Zografos, G. & Almpanopoulos, K. Type 2 diabetes mellitus status in obese patients following sleeve gastrectomy or one anastomosis gastric bypass. Sci. Rep. 11, 4421. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83807-8 (2021).

Gehrer, S., Kern, B., Peters, T., Christoffel-Courtin, C. & Peterli, R. Fewer nutrient deficiencies after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) than after laparoscopic Roux-Y-gastric bypass (LRYGB)—A prospective study. Obes Surg 20, 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-009-0068-4 (2010).

Howard, R. et al. Comparative safety of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass up to 5 years after surgery in patients with severe obesity. JAMA Surg. 156, 1160–1169. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.4981 (2021).

Mokhber, S. et al. Did the COVID-19 pandemic change the weight reduction in patients with obesity after bariatric surgery?. BMC Public Health 23, 1975. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16837-8 (2023).

Funding

This study was funded by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS); Grant Number: IUMS- 1402-3-39-27171.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.B. wrote the manuscript and participated in data interpretation. A.S. conceptualized the study and was involved in data management and data analysis. S.M. and A.P. supervised the study and were involved in the recruitment and care of patients. S.M. and A.S. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boustani, P., Sheidaei, A., Mokhber, S. et al. Assessment of weight change patterns following Roux en Y gastric bypass, one anastomosis gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy using change-point analysis. Sci Rep 14, 17416 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68480-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68480-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Early prediction of suboptimal clinical response after bariatric surgery using total weight loss percentiles

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Estimation of common breaks in linear panel data models via screening and ranking algorithm

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Sleeve Gastrectomy Versus Semaglutide for Weight Loss in a Severely Obese Minority Cohort: A Propensity-Matched Study

Obesity Surgery (2025)

-

Long-Term Outcomes of One Anastomosis Gastric Bypass: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 5-Year and Beyond

Obesity Surgery (2025)

-

Greater durability of weight loss at ten years with gastric bypass compared to sleeve gastrectomy

International Journal of Obesity (2025)