Abstract

The purpose of this study was to understand the dynamic behaviors of lignin-amended loess. Dynamic properties tests of lignin-amended loess with different contents and strength tests at optimum content were carried out by using a hollow cylinder torsion shear apparatus. Firstly, the effect of lignin fiber content (0%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 3% and 4%) on the dynamic properties of improved loess was investigated, and the results showed that the optimal lignin content for improved loess was 1%, at which time compared with pure loess the highest increase of the dynamic shear stress in the skeleton curve of the soil was 73.8%, the increase of dynamic shear modulus was 26%, and the decrease of dynamic damping ratio was 60%; Then, the effects of moisture content (12%, 17%, 21%) and consolidated confining pressure (100 kPa, 200 kPa, 300 kPa) on the dynamic strength of 1% modified loess were studied, and the subsidence characteristics of the improved loess were also focused on, the results indicated that the dynamic strength of the improved loess decreased with the increase of moisture content and increase with the confining pressure, and the seismic characteristics increase with the increase of dynamic shear stress and the number of cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Loess has strong dynamic structural breakage due to its loose large pores, weak cementation, vertical cracks and fissures development of the structure, and is prone to seismic disasters such as subsidence and landslides under strong earthquakes1, so it is necessary to strengthen the loess. Among many methods of soil reinforcement, fiber reinforcement has been widely identified as an effective engineering technology2,3. Fibers can be classified into two categories, synthetic fibers4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 such as nylon7, polyester, and polypropylene9,12,13,14 and natural fibers15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 such as lignin, jute, coconut husk24, and corn stover. Natural fibers have a rough surface, can be well bonded to the soil matrix, they are eco-friendly and economical, so they have received extensive attention from researchers.

Vinayak25 used Grewia Optivia and Pinus Roxburghii fibers to reinforce clay soil, explored the effects of fiber content and age on the compressive strength of the soil. Quang26 studied the effect of corn fiber on the strength of soft soils by unconfined compression test and splitting tension test, they found that the addition of fibers increased the compressive strength and splitting tensile strength of soft soils. Alireza27 found that lignocellulose could improve the shear strength of Sandy soil through triaxial compression test, they analyzed the mechanism of fiber-reinforced soil by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and other techniques. Owino28 investigated the effect of basalt fiber length on the shear strength of clay soil through a series of triaxial compression tests, they found that the increase of basalt fiber filament length significantly increased the deviator stress and increased the cohesion and internal friction angle by 81% and 63%, respectively. The results of the above studies show that fiber reinforcement can indeed improve the mechanical properties of the soil and increase its strength. But most of the existing studies focus on the static properties of fiber-amended soils, which are dominated by triaxial compression tests10,4,29, with less research on the dynamic properties. However, soil-dynamic disasters seriously threaten the life and property safety of the people, for example, the 1999 Taiwan Chi-Chi earthquake caused 2400 deaths and more than 10,000 injuries30, and the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake resulted in 1100 billion yuan of indirect economic losses31, so earthquake mitigation has been a serious and very urgent issue. Therefore, it is necessary to study the dynamic characteristics of fiber-amended soil.

In this study, the effect of fiber content on the dynamic properties of lignin-amended loess was investigated through the dynamic properties test and strength test, and the dynamic strength of amended loess under different moisture contents and confining pressures was analyzed, while the seismic subsidence characteristics of amended loess at optimal content were also paid attention to.

Test materials, apparatus, and methods

Materials

Soil

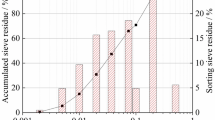

The loess for this test was taken from the construction site of the Happy Forest Belt commercial area in Xi'an City, Shaanxi Province, China. A lateral well was manually opened into the sidewall of the on-site pit to an excavation depth of 5–9 m to obtain an in-situ soil sample in the form of a cube with a side length of 30–40 cm. The loess was classified as Q3 loess according to ASTMD 2487. Table.1 lists the basic physical properties of tested loess, and Fig. 1 shows the particle size distribution of the soil. The soil consists of 8.2% sand, 71.63% silt, and 20.15% clay. The compaction curve is presented in Fig. 2 with an optimal moisture content of 20.97% and a maximum dry density of 1.63 g/cm3.

Lignin

The lignin used in the test came from a Chinese technology company and had a yellowish needle-like fiber (Fig. 3). Table.2 shows the relevant physical property indicators of lignin fiber.

Specimens

All specimens in this test are hollow cylindrical samples with a height of 100 mm, an inner diameter of 30 mm and an outer diameter of 70 mm. The specimen preparation process is as follows: Firstly, the taken loess specimen was crushed, milled and passed through a 2 mm standard geotechnical sieve, and the soil material was formulated to the target moisture content by spraying method; Next, according to the experimental design, lignin with different admixture ratios (mass of lignin to mass of dry soil) of 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% was added to make a homogeneous mix with the wet soil, after which it was placed in a sealed bag for 48 h; Finally, the soil was pressed into a solid cylindrical soil sample with a height of 100 mm and a diameter of 70 mm in four layers using a matching sample-making mold, and then shaved into a hollow cylindrical sample with an inner diameter of 30 mm using a drill cutter in the hollow cylindrical mold after being removed from the mold, and then placed in a humidified cylinder for three days(Fig. 3).

Test apparatus and the stress state of the specimen

The instrument used in the test is the dynamic hollow cylinder torsion shear DTC-199HVS, which is made in Japan SEIKEN Inc. The instrument consists of hydraulic pump, water and air control system, pressure chamber, electrical control cabinet, data collection system and so on (Fig. 4).

As shown in Fig. 5, the specimen is subjected to axial load \(W\), torque \(T\), inner chamber pressure \(P_{i}\) and outer chamber pressure \(P_{o}\) in the dynamic hollow cylindrical torsion shear, which produce four stress components: shear stress \(\tau_{z\theta }\)(caused by torque), radial stress \(\sigma_{r}\) and hoop stress \(\sigma_{\theta }\)(caused by internal and external pressure) and axial stress \(\sigma_{z}\) (caused by both axial force and internal and external pressure). The stress component can be found by Eqs. (1)–(4), Where \(r_{o}\) is the outer radius of the specimen and \(r_{i}\) is the inner radius of the specimen. The hollow cylinder torsion shear apparatus allows for flexibility in the magnitude and direction of the principal stresses, making it an ideal method for soil dynamic testing.

Test plan

Dynamic characteristics test of loess under different levels of lignin

The research objective of this experiment is to obtain the optimal amount of lignin added to loess. The optimal incorporation of lignin was obtained by the effects of six lignin incorporation amounts (0%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%) on the dynamic characteristics of loess. The moisture content of the sample in this test is 21% of the best moisture content obtained by the compaction test, and the confining pressure was 100 kPa. The dynamic shear stress in the test was applied step by step at a frequency of 1 Hz, and according to the Seed principle of equivalent stress, each level of equivalent stress was 10 cycles. At the end of each level of loading, consolidation was carried out under initial static stress conditions for one minute, followed by the application of the next level of load until the specimen fails. Figure 6 shows the torque time history curve of the specimen at load.

Strength and seismic subsidence tests

The single-stage loading method was used to carry out dynamic strength and seismic subsidence tests on the improved loess with optimal lignin admixture, mainly to explore the variation rule of its strength and seismic subsidence characteristics under dynamic loading. During the test, cyclic torsional shear stress was applied to the specimen until the specimen was failed. The test considered three moisture content (12%, 17%, 21%), three consolidation confining pressures (100 kPa, 200 kPa, 300 kPa) and four dynamic shear amplitudes (12 N m, 20 N m, 30 N m, 40 N m). The test plan is shown in Table 3. Figure 7 is the time history curve of cyclic torsional shear stress.

Experimental results and discussion

Effect of lignin fiber content on dynamic properties of loess

The test data of the fifth vibration in each stage of cyclic load is selected to obtain the skeleton curve of improved loess with different lignin content, and its development law is shown in Fig. 8. It is evident that the skeleton curves of pure loess and lignin-amended loess conform to the deformation law of the hyperbolic model, and both show elastic–plastic. Under the same conditions, with the increase of lignin content, the dynamic shear stress of soil increases first and then decreases, and the dynamic shear stress of the improved loess reaches the peak at 1% lignin content, at which time it increases by 73.8% than pure loess. The stress values at 4% lignin content were slightly lower than those of pure loess, indicating that excessive lignin content may even reduce loess strength. The reason is that the soil particles interact with lignin, which creates tensile strength in the lignin and acts on the nearby loess particles to prevent the soil from sliding18. In addition, lignin particles are also attached to the coarse particles of loess, which improves the contact form between large particles in the soil and helps to further enhance the cohesion between particles32. However, when the content is too high, the adhesive properties of lignin itself will promote lignin to preferentially bind with itself, rather than binding particles26. At the same time, the increase of lignin particles between soil particles will increase the distance between soil particles, resulting in a decrease in the attractiveness between particles, making soil particles easier to slide and reducing soil strength.

The dynamic shear modulus of soil is defined as the dynamic shear stress generated by the unit dynamic shear strain of soil, which is one of the important parameters for evaluating the dynamic characteristics of soil. It can be determined from the skeleton curve of the soil body and is commonly described by the Hardin-Drnevich hyperbolic function model, show in Eq. (5).

where \(G_{d}\) is the dynamic shear modulus of the soil, \(\gamma_{d}\) is the dynamic shear strain, \(\tau_{d}\) is the dynamic shear stress, \(G_{0}\) is the initial dynamic shear modulus of the soil,\(\tau_{d\max }\) is the maximum dynamic shear stress, \(a\) is the slope of the function, and \(b\) is the intercept of the function.

Figure 9 shows the variation rule of dynamic shear modulus with dynamic shear strain of improved loess under different lignin contents. The variation trend of the curve under different lignin content is basically the same, with the gradual increase of horizontal torsional shear stress, the accumulation of dynamic shear strain \(\gamma_{d}\) increases, and the dynamic shear modulus decreases rapidly \(G_{d}\) the initial stage and then gradually flattens out. When the dynamic shear strain is the same, the dynamic shear modulus \(G_{d}\) increases firstly and then decreases with lignin content. It is the largest at 1% lignin content and the smallest at 4%. The dynamic shear modulus is increased by 26% at 1% compared with pure loess, which indicates that the optimal content of lignin-amended loess is 1%.

The damping ratio is another important parameter to evaluate the dynamic characteristics of soil, the 5th cycle of dynamic load applied to each stage is selected, and the hysteresis curve can be drawn. The definition of the damping ratio \(\lambda_{d}\) is given in Eq. (6) and its schematic is shown in Fig. 10.

where:\(\Delta S\) is the energy lost in a cycle and \(S\) is the total energy of the action.

Figure 11 presents the effect of different lignin content on the improved loess damping ratio. The dynamic damping ratio is the smallest at 1% lignin content, the largest at 0% content (pure loess), it is 60% lower at 1% lignin content than pure loess. As the dynamic shear strain increases gradually, the damping ratio also increases gradually and shows an approximately linear relationship. The variation of the improved loess damping ratio is significantly affected by the lignin content, because the addition of lignin fibers made the larger pores between the soil particles fully filled, and at the same time, the cohesion between the soil particles increased due to its own cementation32, and the stability and integrity of the soil skeleton were enhanced, which in turn reduced the friction and energy loss of the soil particles under dynamic load, so the damping ratio decreased.

Through the analysis of the dynamic characteristics of loess under different levels of lignin content, combined with economic and environmental benefits, the optimal lignin content is 1%, at which point the improvement effect of lignin on loess is most significant.

Dynamic strength characteristics of improved loess with 1% lignin content

From the previous experimental results, it is evident that the improvement effect of loess is best when the lignin dosage is 1%, thus only focusing on the dynamic strength characteristics of the improved loess at 1% lignin content. The dynamic strength of a soil is the dynamic stress required to produce a certain destructive strain (or to satisfy a certain destructive criterion) under a certain number of cycles. For the horizontal torsional shear test, the dynamic stress is expressed as the horizontal torsional shear stress, so the dynamic strength curve is the \(\sigma_{z\theta } \sim \log N_{f}\) curve.

In this test, both axial and horizontal shear strains were generated in the specimen, and taking into account the effects of these two strains, the failure criterion was chosen to be a generalized shear strain of 5% of the specified value. Calculation of generalized shear strain in Eq. (7).

where \(\gamma\) is generalized shear strain, \(\varepsilon_{z}\) and \(\gamma_{d}\) are axial strain and horizontal shear strain, respectively.

Figure 12 shows the dynamic strength curves of improved loess with 1% lignin content at 12%, 17% and 21% moisture content under different confining pressures. Under the same moisture content, with the increase of confining pressure, the dynamic strength curve of the improved loess gradually increases, and the dynamic strength gradually increases. The reason is that with the increase of confining pressure, the structure in the specimen soil body is squeezed and destroyed, large and medium-sized pores collapse, the voids between soil particles and lignin fibers are further compressed, and the bonding between the two is further enhanced, so that the shear capacity of the improved loess is enhanced with the increase of confining pressure.

Figure 13 shows the dynamic strength curve of 1% lignin content improved loess under the same confining pressure, reflecting the dynamic strength change rule of improved loess with moisture content at the confining pressure of 100 kPa, 200 kPa and 300 kPa, respectively. The dynamic strength of the improved loess gradually decreases with the increase of moisture content when the confining pressure is unchanged. Although the dynamic strength curves all shifted downward with increasing moisture content, the degree of downward shift at different stages was clearly distinguished. For example, the downward shift of the dynamic strength curve from 12 to 17% is significantly smaller than the decrease in the moisture content from 17 to 21%. This suggests that the dynamic strength of improved loess shows a non-uniform trend with the change of moisture content. It is evident that the thickening of the water film between the soil particles and the lignin fibers under the action of water, the reduction of matrix suction, and the weakening of lignin adhesion, resulting in a significant decrease in the dynamic strength of the improved loess at higher moisture content.

Three typical failure patterns appeared after the lignin-improved loess reached the failure standard under the action of horizontal cyclic torsional shear stress of single-stage loading. As shown in Fig. 14a, there is no obvious failure surface of the sample under low moisture content, which may be due to the reinforcement effect of lignin fiber under low moisture content to effectively improve the tensile ability of the specimen, and with the increase of moisture content, the arc-shaped shear failure surface and the oblique through-type shear failure surface shown in Fig. 14b,c gradually appear in the specimen, and the crack deepens with the increase of the number of cycles.

Seismic subsidence characteristics of improved loess with 1% lignin content

In the loess subsidence test, the size of subsidence is usually expressed by the residual strain of the specimen under a certain number of vibrations and a certain cycle of dynamic shear stress, the residual strain is defined as Eq. (8).

where \(\varepsilon\) is the residual strain of the specimen for a certain number of vibration N and a cyclic dynamic shear stress \(\sigma_{z\theta }\), it is usually called the specimen's subsidence coefficient, \(H_{1}\) and \(H_{2}\) are the height of the specimen for the cyclic dynamic shear stress before and after the action.

The seismic subsidence curves at 17% moisture content and 100 kPa, 200 kPa and 300 kPa confining pressures were selected to study the seismic subsidence characteristics of lignin doped 1% improved loess, and the seismic subsidence curves are shown in Figs. 15 and 16. The deformation pattern of the improved loess is basically the same under all vibration frequencies. The seismic collapse coefficient increases with the increase of cyclic dynamic shear stress, indicating that the residual strain of the soil is increasing. Under the small dynamic shear stress, the improved loess began to undergo subsidence and deformation, indicating that the weak structural unit of the soil began to be damaged, and then, with the increase of dynamic shear stress, the structure of the improved loess was further damaged, and the seismic deformation gradually increased. During torsional shear, with the increase of vibration frequency, the axial cumulative deformation of loess develops gradually, and the coefficient of seismic subsidence becomes larger. Meanwhile, comparing the graphs (a) (b) (c) of Figs. 15 and 16, the seismic deformation of the modified loess is decreasing with the increase of the circumferential pressure at a certain moisture content.

Conclusions

The mechanical properties of lignin fiber-amended loess were investigated through dynamic characteristic tests and strength tests, then the following conclusions can be drawn from the test results:

The content of lignin in loess has a significant effect on the dynamic characteristics of soil. Compared with pure loess, the dynamic shear stress in the loess skeleton curve increased by 73.8%, the dynamic shear modulus increased by 26% and the dynamic damping ratio decreased by 60% when the lignin content was 1%; its dynamic characteristics were even lower than pure loess when the lignin content was 4%. The optimal content of improved loess is 1%, and too high content will reduce soil strength.

The dynamic strength of 1% improved loess decreases with the increasing moisture content and increases with the increasing confining pressure. There are three modes of improving loess destructive surfaces.

The seismic collapse characteristics of 1% improved loess are affected by the dynamic shear stress and the number of cycles, and the subsidence coefficient is positively correlated with the dynamic shear stress, which increases with increasing the cycle number.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shao, S., Shao, S. J., Chen, P. & Zhang, B. Experimental study on seismic subsidence characteristics of structural loess under cyclic torsional shear. Yantu Gongcheng Xuebao/Chin. J. Geotechn. Eng. 42, 1167–1173 (2020) ((in Chinese)).

Zhao, Y. et al. Comparative mechanical behaviors of four fiber-reinforced sand cemented by microbially induced carbonate precipitation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 3075–3086 (2020).

Hejazi, S. M., Sheikhzadeh, M., Abtahi, S. M. & Zadhoush, A. A simple review of soil reinforcement by using natural and synthetic fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 30, 100–116 (2012).

Lian, B., Peng, J., Zhan, H. & Cui, X. Effect of randomly distributed fibre on triaxial shear behavior of loess. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 1555–1563 (2020).

Dhar, S. & Hussain, M. The strength behaviour of lime-stabilised plastic fibre-reinforced clayey soil. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 20, 1757–1778 (2019).

Ghorbani, A. & Salimzadehshooiili, M. Evaluation of strength behaviour of cement-RHA stabilized and polypropylene fiber reinforced clay-sand mixtures. Civ. Eng. J. 4, 2628 (2018).

Estabragh, A. R., Bordbar, A. T. & Javadi, A. A. Mechanical behavior of a clay soil reinforced with nylon fibers. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 29, 899–908 (2011).

Tang, C., Shi, B., Gao, W., Chen, F. & Cai, Y. Strength and mechanical behavior of short polypropylene fiber reinforced and cement stabilized clayey soil. Geotextiles Geomembr. 25, 194–202 (2007).

Mishra, B. & Kumar Gupta, M. Use of randomly oriented polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fiber in combination with fly ash in subgrade of flexible pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 190, 95–107 (2018).

Nouri, S., Nechnech, A., Lamri, B. & Lopes, M. L. Triaxial test of drained sand reinforced with plastic layers. Arab. J. Geosci. 9, 1–9 (2016).

Dafalla, M. A. & Ai-Obaid, A. K. Enhancing tensile strength in clays using polypropylene fibers. Int. J. Geomate 12, 33–37 (2017).

Cai, Y., Shi, B., Ng, C. W. W. & Tang, C. Effect of polypropylene fibre and lime admixture on engineering properties of clayey soil. Eng. Geol. 87, 230–240 (2006).

Taha, M. M. M., Feng, C. P. & Ahmed, S. H. S. Influence of polypropylene fibre (PF) reinforcement on mechanical properties of clay soil. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2020, 1–15 (2020).

Chen, M. et al. Laboratory evaluation on the effectiveness of polypropylene fibers on the strength of fiber-reinforced and cement-stabilized Shanghai soft clay. Geotextiles Geomembr. 43, 515–523 (2015).

Abou Diab, A. et al. Effect of compaction method on the undrained strength of fiber-reinforced clay. Soils Found. 58, 462–480 (2018).

Yuan-jun, J. et al. Effect of root orientation on the strength characteristics of loess in drained and undrained triaxial tests. Eng Geol 296, 106459 (2022).

Abou Diab, A., Sadek, S., Najjar, S. & Abou Daya, M. H. Undrained shear strength characteristics of compacted clay reinforced with natural hemp fibers. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 10, 263–270 (2016).

Yixian, W., Panpan, G., Shengbiao, S., Haiping, Y. & Binxiang, Y. Study on strength influence mechanism of fiber-reinforced expansive soil using jute. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 34, 1079–1088 (2016).

Anggraini, V., Asadi, A., Huat, B. B. K. & Nahazanan, H. Effects of coir fibers on tensile and compressive strength of lime treated soft soil. Measurement 59, 372–381 (2015).

Chauhan, M. S., Mittal, S. & Mohanty, B. Performance evaluation of silty sand subgrade reinforced with fly ash and fibre. Geotextiles Geomembr. 26, 429–435 (2008).

Widianti, A., Diana, W. & Alghifari, M. R. Shear strength and elastic modulus behavior of coconut fiber-reinforced expansive soil. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1144, 012043 (2021).

Bordoloi, S., Hussain, R., Garg, A., Sreedeep, S. & Zhou, W.-H. Infiltration characteristics of natural fiber reinforced soil. Transp. Geotech. 12, 37–44 (2017).

Ahmad, F., Bateni, F. & Azmi, M. Performance evaluation of silty sand reinforced with fibres. Geotextiles Geomembr. 28, 93–99 (2010).

Nahar, N., Owino, A. O., Khan, S. K., Hossain, Z. & Tamaki, N. Effects of controlled burn rice husk ash on geotechnical properties of the soil. J. Agric. Eng. 52, 1216 (2021).

Sharma, V., Vinayak, H. K. & Marwaha, B. M. Enhancing compressive strength of soil using natural fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 93, 943–949 (2015).

Tran, K. Q., Satomi, T. & Takahashi, H. Effect of waste cornsilk fiber reinforcement on mechanical properties of soft soils. Transp. Geotech. 16, 76–84 (2018).

Moslemi, A., Tabarsa, A., Mousavi, S. Y. & Aryaie Monfared, M. H. Shear strength and microstructure characteristics of soil reinforced with lignocellulosic fibers-Sustainable materials for construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 356, 129246 (2022).

Owino, A. O. & Hossain, Z. The influence of basalt fiber filament length on shear strength development of chemically stabilized soils for ground improvement. Constr. Build. Mater. 374, 130930 (2023).

Lal, D., Sankar, N. & Chandrakaran, S. Triaxial test on saturated sands reinforced with coir products. Int. J. Geotechn. Eng. 13, 270–276 (2019).

Lin, J. H., Lin, Y. J. & Tan, Y. J. Research on earthquake loss estimation approach and its application. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 39, 373–380 (2017) ((in Chinese)).

Zheng, S. S. et al. Method and application of economic loss assessment for earthquake disasters. J. Catastrophol. 35, 94–101 (2020) ((in Chinese)).

Prabakar, J. & Sridhar, R. S. Effect of random inclusion of sisal fibre on strength behaviour of soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 16, 123–131 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Fund project (52108342) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (No. 2024JC-YBQN-0605 and 2024JC-YBMS-427).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sj.Shao gave the experimental programme, D.Guo and Rf.Guo did the experiments, and D.Guo wrote the main manuscript.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, D., Shao, S. & Guo, R. Experimental study on the dynamic behavior of lignin-amended loess. Sci Rep 14, 17404 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68505-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68505-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Anisotropy and microscopic mechanism of lignin-modified loess

Journal of Mountain Science (2025)