Abstract

Water scarcity and droughts are among the most challenging issues worldwide, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions like Saudi Arabia. Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.), a major crop in Saudi Arabia, is being significantly affected by water scarcity, soil salinity, and desertification. Alternative water sources are needed to conserve freshwater resources and increase date palm production in Saudi Arabia. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia has a significant number of aquaculture farms that generate substantial amounts of wastewater, which can be utilized as an alternative source of irrigation. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the potential of aquaculture wastewater as an alternative irrigation source for date palm orchards. Aquaculture wastewater was collected from 12 different farms (Al-Kharj, Al-Muzahmiya, and Al-Qassim regions, Saudi Arabia) and its quality was analyzed. The impacts of aquaculture wastewater irrigation on soil quality, nutrient availability, nutrient status of date palm trees, and dates fruit quality were assessed in comparison to source water (freshwater) irrigation at Al-Kharj, Al-Muzahmiya, and Al-Qassim regions. The water quality analyses showed higher salinity (EC = 3.31 dSm−1) in farm Q3, while all other farms demonstrated no salinity, sodicity, or alkalinity hazards. Moreover, the aquaculture wastewater irrigation increased soil available P, K, NO3−–N, and NH4+–N by 49.31%, 21.11%, 33.62%, and 52.31%, respectively, compared to source water irrigation. On average, date palm fruit weight, length, and moisture contents increased by 26%, 23%, and 43% under aquaculture wastewater irrigation compared to source water irrigation. Further, P, K, Fe, Cu, and Zn contents in date palm leaf were increased by 19.35%, 34.17%, 37.36%, 38.24%, and 45.29%, respectively, under aquaculture wastewater irrigation compared to source water irrigation. Overall, aquaculture wastewater irrigation significantly enhanced date palm plant growth, date palm fruit quality, and soil available nutrients compared to freshwater irrigation. It was concluded that aquaculture wastewater can be used as an effective irrigation source for date palm farms as it enhances soil nutrient availability, date palm growth, and date fruit yield and quality. The findings of this study suggest that aquaculture wastewater could be a viable alternative for conserving freshwater resources and increase date palm production in Saudi Arabia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The continued growth of the global population has led to an intensive increase in food and water demand while simultaneously causing a decline in the availability and quality of water resources. It has been predicted that a significant increase in food and water demand will occur in the coming decades1. Thus, increasing food production and conserving global freshwater resources have become major challenges to socio-economic development worldwide. It is estimated that the water usage will increase by 50% in the coming 30 years, leading approximately 4 billion people, i.e., half of the world’s population to face acute water shortage by 2030, primarily in Africa, Middle-East and South Asia2. The water situation in the Middle-East is also alarming because the population in the Middle-Eastern countries has increased over the last few decades3. Due to the hot and arid climate and minimal rainfall, Saudi Arabia is facing extreme water scarcity4. Saudi Arabia fulfils its major water requirement through the use of fossil and non-renewable water extraction, consequently these resources are depleting rapidly5. On the other hand, the available water resources have been polluted by the anthropogenic activities, consequently posing a great challenge in the availability of good quality water6. Therefore, water scarcity and poor water quality are the challenging problems worldwide and in Saudi Arabia in particular. This situation needs immediate attention to conserve available water resources and explore alternative water resources for agricultural, municipal, and industrial utilization.

Water shortages and desertification have significantly reduced the productivity of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) over the last decade in Saudi Arabia7. As date palm is one of the major crops contributing to the agroecosystems and economy of Saudi Arabia; therefore, the decline in date palm production could impact the socio-economic development of Saudi Arabia. Due to desertification, climate change, and degradation of land and water, enhancing the productivity of date palm in arid and semi-arid regions such as Saudi Arabia, is extremely difficult and challenging8. Fresh water is the most important commodity in Saudi Arabia9. Extracting groundwater for irrigation and other purposes is financially prohibitive due to its depth, rendering it impractical compared to the cost of production. Meanwhile, in alignment with Vision-2030, Saudi Arabia seeks to substantially increase seafood production, for which aquaculture farms are producing enormous amount of wastewater on daily basis10. Reusing aquaculture wastewater emerges as a promising solution for addressing the dual concerns of water conservation and improving date palm production. It has been estimated that only approximately 5% of the land in Saudi Arabia is arable due to the harsh environment and desert climate, and therefore, date palm production is at risk due to water scarcity and climate change impacts11. Thus, the production technologies for date palm must be improved by considering alternative water resources and by enhancing water use efficiency.

It has been estimated that the agriculture sector consumes almost 80% of the total freshwater resources in Saudi Arabia and it would be the most affected sector facing water scarcity in the future12. Irrigation is the primary way to secure food production as approximately 40% of the world’s crops are being cultivated on irrigated lands13. Thus, the improvement of agricultural production and water use efficiency in arid and semi-arid regions is one of the biggest challenges. A possible technique to raise the “crops per drop” would be to integrate aquaculture into existing agricultural systems. Globally, 167 million tons of fish are being produced and out of which 73.8 million tons (44%) of demand is fulfilled by the aquaculture sector, which can be further increased to 70%14. Aquaculture is providing food to about 7 billion people worldwide15. The production of food using aquaculture also needs a significant amount of water to be used.

Reusing wastewater is a crucial component of water resource planning in many countries, especially in arid regions such as Saudi Arabia. This situation has compelled many countries to consider sustainable management strategies for water resources. Therefore, the reuse of wastewater has been receiving significant attention worldwide16. Using treated wastewater as irrigation water can potentially reduce the consumption of freshwater and protect the environment from contaminants associated with wastewater disposal. Moreover, it adds essential nutrients to soil such as phosphorus (P), potassium (K), nitrogen (N), and organic matter. However, the occurrence of potentially toxic compounds in wastewater may adversely affect human and environmental health. Ganjegunte et al.17 and Muyen et al.18 reported that wastewater could contain huge quantities of heavy metals and soluble salts, which may result in the buildup of heavy metals and salts in soil over time. Some of the other studies demonstrated that wastewater irrigation could result in the accumulation of toxic elements in the soil profile19,20. Likewise, the accumulation of salts in soil could deteriorate soil quality, subsequently hindering plant growth21. It has recently been reported that continuous irrigation with wastewater results in the accumulation of heavy metals in soil and plants22,23. Therefore, proper care should be taken before using wastewater irrigation, as it may contain potentially toxic pollutants as well as salts.

Integrated aquaculture-agriculture favors the efficient use of water, specifically in arid and semi-arid regions24. Integrated aquaculture-agriculture could improve the fish pond water quality, reduce the adverse environmental impacts of discharging nutrient-rich wastewater, reduce the amount of chemical fertilizers needed for crop production, and diversify the production of farms with increased income and improved water efficiency25. The addition of aquaculture to the existing agriculture system makes it a non-consumptive prolific part that doesn’t compete with irrigation.

It has been reported that N use efficiency by the fish is less than 50%, while about 70%–80% of the mineral resources as part of nutrients are converted into waste26. Likewise, fish can consume about 15%–40% P, while about 70% P is released as waste into the water26. Therefore, this kind of irrigation system doesn’t need additional fertilizers because aquaculture water contains numerous important constituents, especially P and N which are essential macronutrients for improving crop growth and production27. Furthermore, it contains dissolved or particulate organic (organic/inorganic) matter, which could influence the hydrophobicity and hydraulics of soil, ultimately leading to better crop yields28. It has been reported that aquaculture wastewater saved more than 40% of nutrients uptake with increasing plant biomass26. The aquaculture wastewater helps to remediate environmental degradation and water conservation. The wastewater produced by aquaculture also helps to improve the fertility of sandy soils which are very deficient in plant nutrients and improves crop productivity29. However, reusing wastewater discharged from aquaculture units needs intensive care and feasible production practices to minimize negative ecological impacts, since large volumes of untreated wastewater are directly discharged into soil and fresh water bodies30. Further, aquaculture wastewater is characterized by low chemical oxygen demand and higher ammonia concentration mainly due to un-consumed fish feed, which needs special consideration and treatment to be reused it for soil applications and agricultural activities.

Therefore, reusing aquaculture wastewater for irrigation could be a cheaper strategy to save freshwater and groundwater resources on one hand, and can increase soil fertility and plant productivity on the other hand due to the presence of nutrients and organic matter. Hence, this research was conducted to (1) assess the potential of reusing aquaculture wastewater for irrigation in agriculture, (2) assess the impacts of aquaculture wastewater irrigation on soil quality and nutrients availability, and (3) investigate the impacts of aquaculture wastewater irrigation on quality and production of date palm fruits.

Materials and methods

Study area

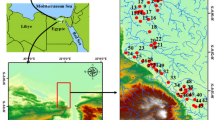

This research was situated in three regions, which are Al-Kharj, Al-Muzahmiya, and Al-Qassim in Saudi Arabia. Al-Kharj is located 77 km south of Riyadh at around 24º 8ʹ 54ʺ N and 47º 18ʹ 18ʺ E, and it contains a desert climate with a higher temperature (23–45.5 °C) and minimum rainfall (67 mm annually). Al-Kharj is famous for its agricultural, fisheries, and dairy production. Al-Muzahmiya is located about 60 km west of Riyadh city, while Al-Qassim is located in the middle of Saudi Arabia, which is about 400 km northwest of Riyadh city. Al-Muzahmiya is comprised of a desert climate with 9.57 mm of mean precipitation. Al-Qassim remains dry for the whole year, except for some rainfall in the winter season. The average summer temperature of Al-Qassim ranges between l7 °C and 46 °C.

Aquaculture water samples collection and quality assessment

The samples from source water, aquaculture ponds, and aquaculture wastewater were collected from different farms located in Al-Kharj, Al-Muzahmiya, and Al-Qassim regions as shown in Fig. 1. Aquaculture water samples were collected from 12 different aquaculture farms, 3 of which were located in Al-Kharj (K1, K2, and K3), 3 were located in Al-Muzahmiya (M1, M2, and M3, and 6 were located in Al-Qassim region (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5, and Q6). A composite water sample was collected with 3 replications from each type i.e., source (freshwater), pond, and aquaculture wastewater. Briefly, the samples were collected in a 2 L polyethylene plastic container from a depth of 0.5 m in the aquaculture ponds and wastewater reservoir. Source water was collected from continuous flow of water from the wells. There was one well on each of the studied farms to withdraw groundwater. A total of 233 samples including sources of water, aquaculture pond, and wastewater drainage were collected. The temperatures of the pond and wastewater drainage reservoir was noted during water sample collection.

Geographical locations of the sampling points in Al-Kharj (K1, K2, and K3), Al-Muzahmiya (M1, M2, and M3), and Al-Qassim (Q1 to Q6), Saudi Arabia. The map was developed using Google Maps, Map Data ©2024, https://mymaps.google.com.

After the collection, the aquaculture water samples were directly transported to the laboratory (Department of Soil Science, College of Food and Agricultural Science, King Saud University Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) and kept at 4℃ for analyses. The collected aquaculture water samples were subjected to physical and chemical analyses immediately upon arriving at the laboratory. A portion of the water samples were filtered using Whatman No. 42 filter papers for chemical analyses, while unfiltered samples were used for some physiochemical analyses. The electrical conductivity (EC) of the water samples was measured by an electrical conductivity meter (YSI Model 35), while pH was measured with a pH meter directly (WTW-pH 523). Soluble cations (Na, K, Mg, and Ca), P, ammonium (NH4+–N), and nitrate (NO3−–N) in all the water samples were analyzed by following the standard protocols. The concentrations of P and K were analyzed with spectrophotometer (Lambda EZ 150) and flame photometer (AE-EP8501, A&E Lab., UK), respectively, while the concentrations of micronutrients (Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn) in water samples were determined with an Inductivity coupled plasma optical emission spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer Optima 4300 DV, USA).

Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR) of water, also called sodium risk, was determined using Eq. 1:

Impacts of aquaculture wastewater irrigation on soil and date palm fruits

A total of 6 date palm farms (2 in Al-Kharj, 1 in Al-Muzahmiya, and 3 in Al-Qassim) were selected for investigation in this study based on the irrigation water type. The method of irrigation at all the studied farms was drip irrigation. In all of the selected farms, part of the farmland was being irrigated with freshwater, while another part was being irrigated with aquaculture wastewater by the farmers for a minimum of 2 years. Both parts of each farm, regardless of whether they were irrigated with aquaculture wastewater or freshwater, were managed in a similar way throughout the study duration. Soil samples from the selected date palm farms were collected during the harvesting seasons. Composite soil samples were collected from 0 to 30 cm, 30 to 60 cm, and 60 to 100 cm depth from different locations in each orchard. The soil samples were collected with the help of auger into polythene bags, then brought to the lab and stored at 4 °C. Overall, 249 soil samples were collected.

For the collection of date palm leaf and fruit samples, permissions were acquired from the farm owners prior to the sampling. Moreover, the study was conducted in compliance with national and international regulations regarding the collection of plant specimens, and in accordance with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. A total of 105 date palm leaf and 38 date palm fruit samples were collected from all farms. Mature and undamaged tree leaf samples were collected. Likewise, mature and fully ripened date palm fruit samples were also collected and stored in paper bags.

The collected soil, and date palm (fruit and leaf) samples were prepared and subjected to further analyses. The soil samples were dried in the air, ground, and passed through a 2-mm sieve, and subjected to further physio-chemical analyses. The date palm fruit and leaf samples were washed with tap water, followed by de-ionized water to remove dust and dirt particles, and then dried in air. The EC and pH of soil samples were measured in 1:2.5 soil to water ratio suspension. Soil organic matter was determined by following the method of Walkley–Black method31. The cation exchange capacity (CEC) of soil was analyzed by standard methods. The concentrations of Na, K, Mg, and Ca, P, NH4+–N, and NO3−–N in all soil samples were analyzed by following the standard protocols. The concentrations of K32 were analyzed with a flame photometer, and P33 was analyzed with a spectrophotometer. Available micronutrients in soil samples were extracted using ammonium bicarbonate-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (AB-DTPA) and determined using an Inductivity coupled plasma optical emission spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer Optima 4300 DV, USA). The SAR of soil samples was determined using the aforementioned Eq. (1).

The fresh weight, length, diameter, and moisture contents of the fruit samples were estimated. The date palm leaf and fruit samples were digested with the wet-digestion method according to the method reported by Wolf32 and the digestate was subjected to further analyses. The contents of micronutrients in samples were analyzed with ICP-OES. The concentrations of K were analyzed with a flame photometer, and P was analyzed with a spectrophotometer (Lambda EZ 150). The contents of total and soluble sugars in fruit samples were analyzed with the help of spectrophotometry34.

Statistical analyses

The mean and standard deviations of the acquired data were computed using descriptive statistics. Statistical analysis of the collected data was performed using the Statistix 8.01 software. Least significant difference (LSD) test was employed to compare the means35.

Results and discussion

Aquaculture wastewater quality assessment

pH, EC, cations, and anions

The results of the average pH, EC, cations, and anions, of the collected source water, pond water, and wastewater samples of aquaculture farms in Al-Kharj, Al-Muzahmiya, and Al-Qassim regions, Saudi Arabia are presented in Table 1. The results of pH indicated that the pH of the source water was slightly lower in all the samples, which increased slightly in the pond water and wastewater samples. Not much variation was found in the pH range of all collected water samples and pH was found in the range of 7.29–8.26. According to FAO36 the suitable range of irrigation water pH is 6.5–8.4, while our findings showed that the pH of wastewater collected from all studied farms was in the range of 7.40–8.26, which makes it suitable for irrigation. The pH beyond this range could cause nutritional imbalances and toxic impacts on plant health37.

Water quality for irrigation can vary greatly, mainly depending on salt type and quantity. The obtained results showed a maximum EC value of 3.10 dSm−1 in Al-Kharj farm K2 wastewater, while the lowest EC value of 0.53 dSm−1 was reported in Al-Qassim farm Q5 source water. The analysis of the collected water samples revealed that the aquaculture wastewater generally exhibited a higher EC compared to the other water types. Overall EC values of water samples were found to be in the suitable range38 with one exception (Al-Kharj farm K2 wastewater) and water is credited as suitable for irrigation. Also, according to Saha et al.39, an EC range of 0.03–5 dSm−1 is suitable for aquaculture rearing. Therefore, our results indicated that each type of water (source water, pond water, and wastewater) is fit for irrigation.

Additionally, the mean concentrations of Ca+2, Mg+2, Na+, and HCO3− were found to be lower in each kind of water sample in the Al-Kharj region, while these concentrations were comparatively higher in Al-Muzahmiya (M1–M3) and Al-Qassim farms (Q1–Q6). According to the US Salinity Laboratory40 and FAO41, concentrations of Ca+2, Mg+2, and Na+ were in the permissible range, and tested water samples were credited suitable for irrigation. In addition to this, SAR values of all collected water samples were below the lowest allowable limit of 10 meq L−140,41 which further endorsed the suitability of tested water samples for irrigation purposes. In brief, all water samples showed variations in pH, EC, cationic, and anionic concentrations, with the highest concentrations found in wastewater which was obvious due to the contents of suspended organic compounds and unconsumed fish feed. However, all observed parameters showed values below the permissible limit, which makes water samples (source water, pond water, and wastewater) suitable for irrigation.

Nutrients status of aquaculture wastewater

The quality of irrigation water plays a major role in soil quality and crop productivity. Adequate amounts of macro- and micronutrients in wastewater are one of the critical factors determining the impacts of such irrigation water on soil and plant health. So, the collected water samples from visited aquaculture farms were analyzed for their nutrient concentrations, including P, N (NO3−, NH4+), K, and micronutrients such as Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn (Figs. 2 and 3). Our findings showed that moderate NH4+–N contents were found in farm K1 aquaculture wastewater samples, while very low concentrations of NH4+–N were found in the rest of the collected water samples. A similar range was observed in all collected pond and wastewater samples from all visited aquaculture farms. Generally, source water was found with the lowest NH4+–N concentrations, while slightly higher NH4+ concentrations were found in wastewater samples except for farm Q3. Nitrate (NO3−–N) concentrations were found maximum in wastewater samples of farms K2 (24.9 mg L−1), Q3 (15.36 mg L−1), Q4 (21.48 mg L−1), and Q6 (13.27 mg L−1), respectively. No significant difference was found in NO3−–N concentration among collected pond and wastewater samples, while NO3−–N concentrations generally were substantially lower in source water in comparison to pond and wastewater samples. Thus, the concentration of N (NO3−) in all the samples was lower as compared to NSW42 guidelines (50 mg L−1) for irrigation water. On the other hand, P concentration was found consistently low in all collected water samples from all visited farms. Water samples from Al-Kharj aquaculture farms showed a slightly higher concentration of P in pond water (0.22 mg L−1) followed by source water (0.16 mg L−1) and wastewater (0.14 mg L−1), while consistently low P concentrations with no significant difference was found in Al-Muzhamiya farms collected water samples. However, wastewater (3.33 mg L−1), pond water (1.77 mg L−1), and source water (0.40 mg L−1) samples from the Q3 farm in Al-Qassim showed comparatively higher concentrations of P than other visited farms. Detected concentrations of P were lower than long-term trigger values of P as recommended by Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council and Agriculture and Resource Management Council of Australia and New Zealand43 and NSW42 (10 mg L−1).

Average concentrations of (a) ammonium (NH4+), (b) nitrate (NO3−), (c) phosphorus, and (d) potassium in water samples (SW: source water, PW: pond water, and WW: wastewater) collected from aquaculture farms located in Al-Kharj (K1, K2, and K3), Al-Muzahmiya (M1, M2, and M3), and Al-Qassim (Q1 to Q6), Saudi Arabia.

Average concentrations of micronutrients (a) iron (Fe), (b) copper (Cu), (c) manganese (Mn), and (d) zinc (Zn) in water samples (SW: source water, PW: pond water, and WW: wastewater) collected from aquaculture farms located in Al-Kharj (K1, K2, and K3), Al-Muzahmiya (M1, M2, and M3), and Al-Qassim (Q1 to Q6), Saudi Arabia.

These results suggested no harmful impacts of using such water in irrigation, as there are minimal chances of N and P toxicities and eutrophication. Additionally, K concentrations in analyzed aquaculture water samples followed a similar trend. The aquaculture wastewater samples had the highest concentrations of K, while the source water samples showed the lowest K levels. The higher concentrations of nutrients like K found in the discharged wastewater from aquaculture farms can be attributed to the feces of the aquatic animals as well as uneaten and undecomposed feed. It is estimated that 50%–90% of the N and over 85% of the P content in the feed ends up being discharged unconsumed in the aquaculture wastewater44,45. The calculated values of observed NH4+–N, NO3−–N, P, and K were found below permissible limits and water was found fit for irrigation46,47. Previous research showed positive impacts of using wastewater on soil fertility48, where a significant increase in the status of soil P, N, and K was observed after irrigation with wastewater. Similarly, Urbano et al.49 reported significant improvements in soil fertility and nutrient status with wastewater irrigation; however, no hazardous impacts of such irrigation were observed. Other studies on aquaculture farming have reported a concentration of 0.35–40.67 mg L−1 for NO3−–N, 0.12–1.746 mg L−1 for NH4+–N, 0.66–8.82 mg L−1 for P, and 212 mg L−1 for K in aquaculture discharged wastewater, which is quite similar to our findings from this study15,45,50,51,52,53.

In all the collected water samples, no significant differences were found in the concentrations of Zn, Fe, Cu, and Mn among different aquaculture farms (Fig. 3). Overall, aquaculture pond water and wastewater showed higher concentrations as compared to source water concentrations of micronutrients, except Fe in farm K3. The relatively higher concentrations of Fe and Mn than Zn and Cu could be due to the unconsumed feed and undissolved organic waste compounds in pond water and wastewater. According to the standard limits of FAO, the maximum concentrations of Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn should not exceed 0.20, 5.00, 0.20, and 2.00 mg L−1, respectively, in irrigation water37. Therefore, the concentrations of Fe, Cu, and Zn in all the tested samples were within the safe limits for heavy metals toxicity in irrigation water as recommended by FAO54. Hence, reusing this aquaculture wastewater for irrigation could supply micronutrients, especially Fe and Mn, to date palm trees, subsequently enhancing tree growth and fruit production. Rusan et al.48 has previously reported that wastewater irrigation could potentially improve nutrients supply to plants, consequently enhancing crop production. Due to the presence of micronutrients, aquaculture wastewater could be a valuable source of maintaining soil fertility by providing nutrients and organic matter, which can result in higher plant productivity. In general, aquaculture wastewater contains higher quantities of solid waste (also known as particulate organic matter) and wide range of chemicals and therapeutic substances, which largely depend on the culture system of aquatic animal species, type of feed, and general management practices55. Such kind of waste is categorized in three forms which are suspended solid contents accumulated at the bottom of the water tank, floating solid waste, and fine waste dissolved in water. Discharge of such kind of aquaculture wastewater may result in a remarkably higher accumulation of organic matter and nutrients in the soil; however, it could also introduce environmental pollution56. Thus, before the application of aquaculture wastewater for crop irrigation and other agricultural practices, there is a need to analyze the wastewater for nutrients status and their toxicities. Our results suggested that aquaculture wastewater from all the studied farms could potentially be used as irrigation water to increase the nutrient availability in the soil without inducing toxicity.

Impacts of aquaculture wastewater on soil quality

The impacts of aquaculture wastewater on soil physio-chemical properties were investigated at all the selected orchards. Aquaculture wastewater contains P, N (NO3− and NH4+), and K, and therefore, irrigating soils with such water may increase soil fertility and nutrient status. However, it must be analyzed before its application in agriculture as it may also cause some serious environmental issues due to the quantitively higher concentrations of some compounds. The results showed that the P, NO3−–N, NH4+–N, and K concentrations in aquaculture wastewater irrigated soils were higher than source water irrigated soil at all soil depths (Fig. 4). Generally, results showed that available macronutrient (N, P, and K) concentrations were in the range of low to marginal levels, suggesting no toxicity57,58. Further, the results revealed that micronutrient (Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn) concentrations in soil (at all soil depths) were higher at all sites after irrigating with aquaculture wastewater. The higher concentrations of micronutrients in aquaculture wastewater irrigated soil could be due to the higher contents of micronutrients in wastewater effluents released from aquaculture farms. The higher concentrations of micronutrients at variable soil depths showed a mixing of micronutrients on surface soil and also lateral movement of these nutrients toward sub-surface soil. These results suggested that irrigation with aquaculture wastewater could improve the status of micronutrients in soil, indicating the higher potential of such wastewater in enhancing soil quality and subsequent date palm productivity. The positive impacts of aquaculture wastewater on soil health and nutrients status have already been reported. For instance, Akindele et al.59 demonstrated improved soil nutrients following the irrigation with aquaculture wastewater in a sweet pepper (Capsicum annum L) farm. Likewise, Urbano et al.49 suggested that wastewater could have two-fold higher nutrients than source water, and therefore, irrigation with such wastewater can reduce fertilizer needs and improve soil and crop quality. In another study, Sun et al.60 reported a significant increase in soil organic carbon, total P, and total N in mangrove soils after irrigating with aquaculture wastewater. The results of this study showed that soil nutrients were increased under aquaculture wastewater irrigation as compared to the source water irrigation. Hence, using wastewater from aquaculture for irrigation purposes may be a fruitful way of increasing agricultural productivity, as it could potentially improve soil health and nutrient availability. Likewise, using this wastewater could be a means for sustainable environment as it reuses the wastewater. Therefore, aquaculture wastewater is recommended for irrigation after proper pre-analyses.

Effects of source water (SW) and aquaculture wastewater (WW) irrigation on available concentrations of soil (a) phosphorus, (b) nitrate (NO3−), (c) ammonium (NH4+), (d) potassium, (a) iron (Fe), (b) copper (Cu), (c) manganese (Mn), and (d) zinc (Zn) in soil samples collected from aquaculture farms located in Al-Kharj (K1 and K2), Al-Muzahmiya (M1), and Al-Qassim (Q1, Q2, and Q3), Saudi Arabia. (A: 0–30 cm, B: 30–60 cm, C: 60–100 cm).

Impacts of aquaculture wastewater on the nutrient’s status of date palm tree leaves

The concentrations of P and K in the date palm leaves as affected by source water and aquaculture wastewater irrigations are presented in Fig. 5. A total of 6 farms were selected among all 12 visited farms to observe the effect of different types of irrigation (source water and wastewater) on the nutrient contents of date palm leaves. In Al-Kharj farms (K1 and K2) no significant differences were found in P and K concentrations of date palm leaves irrigated by source water (P = 0.19–0.20 mg kg−1, K = 2.89–4.31 mg kg−1) and wastewater (P = 0.20–0.23 mg kg−1, K = 3.73–4.60 mg kg−1). However, aquaculture farms in Al-Muzahamiya and Al-Qassim (M1 and Q1–Q3) indicated comparatively higher concentrations of P and K in date palm leaves in wastewater (P = 2.02–2.44 mg kg−1, K = 7.53–14.90 mg kg−1) irrigated plants against source water irrigated plants (P = 1.66–2.05, K = 5.38–12.43 mg kg−1). Higher concentrations of nutrients in wastewater irrigated plant’s leaves could be due to the soluble fraction of these nutrients and also due to nutrient release from unconsumed fish feed residues and suspended organic compounds.

Impacts of source water (SW) and aquaculture wastewater (WW) irrigation on the concentrations of (a) phosphorus (P), (b) potassium (K), (c) iron (Fe), (d) copper (Cu), (e) manganese (Mn), and (f) zinc (Zn) in date palm tree leaves collected from the date palm trees grown in Al-Kharj (K1 and K2), Al-Muzahmiya (M1), and Al-Qassim (Q1, Q2, and Q3), Saudi Arabia.

The concentrations of micronutrients (Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn) in date palm leaves grown on soils irrigated with source water and aquaculture wastewater are shown in Fig. 5. Overall, the concentrations of micronutrients increased in date palm trees grown with aquaculture wastewater irrigation compared to the source water irrigation. A higher concentration of micronutrients in date palm trees grown under aquaculture wastewater irrigation suggested that such water was rich in the soluble fraction of micronutrients61. Several studies demonstrated the positive impacts of wastewater on plant growth26,27. Before utilizing wastewater for irrigation purposes, it is crucial to conduct a comprehensive analysis to assess the status of nutrients and the presence of any toxic substances17,18,19,20. If the analysis identifies the need for treatment, the wastewater should be appropriately treated before being reused for irrigation, whenever necessary.

Irrigation with wastewater is a common practice in some developing countries of Asia and Africa, which is a win–win situation for farmers62. The fast growth rate of the aquaculture species (fish and shrimps) with rapid exchange rates of water in the ponds results in leaving a large portion of feed and nutrients in wastewater during the production period. Moreover, the feces and excreta of the fish contain a portion of undigested feed that get mixed into the wastewater. Therefore, aquaculture wastewater contains feces, undecomposed feed, organic matter, and other elements such as N, P, and Fe63. The application of such nutrient-enriched wastewater in irrigation may result in improved soil health and nutrient availability to the plants. Delaide et al.64 found that wastewater could contain significant amounts of nutrients such as N, P, and K. These nutrients can be absorbed by plants and subsequently accumulate in their leaves and fruits. This suggests that the wastewater from aquaculture could potentially be utilized as a source of fertilizer to support plant growth. The wastewater likely contains essential macronutrients that are crucial for healthy plant development, offering the opportunity to utilize this resource effectively.

The results of this study suggest that aquaculture wastewater could be used effectively for irrigation purposes. The wastewater contains organic and inorganic materials, as well as micro- and macronutrients, that could enhance soil health and fertility. Applying aquaculture wastewater for irrigation may increase crop productivity by improving soil conditions. Furthermore, reusing aquaculture wastewater for irrigation could reduce input costs for agricultural production by eliminating the need for some fertilizers. This would also help facilitate a more circular economy by reusing wastewater instead of discharging it. Overall, the findings indicate that aquaculture wastewater is a valuable resource that can be recycled for beneficial agricultural use, improving both economic and environmental sustainability.

Impacts of aquaculture wastewater on date palm fruit quality

Figure 6 illustrates the effects of the freshwater and aquaculture wastewater irrigation on date palm fruit quality at all studied farms. Overall, it is obvious from the results that aquaculture wastewater irrigation resulted in improved moisture, fruit fresh weight, diameter, and length compared to source water irrigation with different proportions. In general, average date palm fruit weight, length, diameter, and moisture contents were 7.92 g, 3.51 cm, 2.17 cm, and 13.61%, respectively, in Al-Kharj farms irrigated by source water, while wastewater irrigation enhanced date palm fruit growth by an average fruit weight, length, diameter and moisture contents of 10.07 g, 3.82 cm, 2.42 cm, and 19.48%, respectively, which indicated positive impacts of wastewater irrigation on fruit growth. On the other hand, a similar trend of enhancing date palm fruit weight (10.05–14.93 g), fruit length (3.13–4.05 cm), fruit diameter (2.10–2.70 cm), and moisture percentage (14.33–25.5%) was found in Al-Muzhamiya and Al-Qassim farms irrigated by wastewater. Moreover, almost two-fold increase in P contents of fruit was noted in Al-Kharj farms irrigated by wastewater (797.60 mg kg−1), which was 429.75 mg kg−1 in farms irrigated by source water, while contrarily K concentration was decreased to 568 mg kg−1 in wastewater irrigated plants which was 802.17 mg kg−1 under source water irrigation. On the other hand, an increasing trend in P and K concentration in date palm fruits was found under wastewater irrigation in Al-Muzhamiya and Al-Qassim farms. The increment in fruit size, quality, and nutrient contents could be due to the rich soluble contents of plant available nutrients in wastewater against source water, which endorses that aquaculture wastewater could be used as a source of irrigation for better plant growth65. Similarly, the soluble sugar contents of date palm fruits were increased by 2–3 fold in Al-Kharj wastewater irrigated farms, while up to a 24% increase in soluble sugar contents was noted in Al-Muzhamiya and Al-Qassim farms. Manifolds increase in the Fe, Cu, Zn, and Mn contents of date palm fruit were noted in Al-Kharj farms as affected by wastewater irrigation. Average values of Fe, Cu, Zn, and Mn contents in date palm fruit irrigated by source water were 25.50 mg kg−1, 0.05 mg kg−1, 2.62 mg kg−1, and 1.05 mg kg−1 which increased to 106.13 mg kg−1, 0.083 mg kg−1, 8.64 mg kg−1 and 14.02 mg kg−1 respectively, under wastewater irrigation (Fig. 7).

Impacts of source water (SW) and aquaculture wastewater (WW) irrigation on (a) fresh weight, (b) length, (c) diameter, (d) moisture, (e) total sugars, and (f) soluble sugars contents in dates fruits collected from the date palm trees grown in Al-Kharj (K1 and K2), Al-Muzahmiya (M1), and Al-Qassim (Q1, Q2, and Q3), Saudi Arabia.

Impacts of source (fresh) water and aquaculture wastewater irrigation on the concentrations of (a) phosphorus (P), (b) potassium (K), (c) iron (Fe), (d) copper (Cu), (e) manganese (Mn), and (f) zinc (Zn) in date fruits collected from the date palm trees grown in Al-Kharj (K1 and K2), Al-Muzahmiya (M1), and Al-Qassim (Q1, Q2, and Q3), Saudi Arabia.

These results suggested that the aquaculture wastewater used is a good source of micronutrients as irrigation water. Similar results were found by Galal66, who demonstrated that irrigation with wastewater to citrus plants improved the fruit weight and yield of the citrus crops due to the presence of nutrients in the wastewater. In another study, Ofori et al.67 reported that treated wastewater could potentially promote sustainable agriculture and water management. This is because the wastewater can provide valuable nutrients to the soil, while also offering a means to reuse limited water resources. Moreover, an increase in the concentrations of Fe, K, Mn, Zn, Ni, and Na in citrus fruits were observed with wastewater irrigation. Therefore, aquaculture wastewater could be used as an alternative to irrigating date palm orchards to increase date palm tree productivity and the quality of date palm fruits. Irrigation with wastewater resulted in higher plant growth and larger fruit size and nutrient contents; however, such irrigation schemes must be investigated on a long term basis. Previously, the accumulation of heavy metals, soluble salts, as well as undecomposed and undissolved organic compounds have been observed in soils receiving wastewater irrigation for a long time30,68. The accumulation of such soluble salts may enhance soil alkalinity and severely disturb soil texture and soil structure, which may decrease soil moisture and bioavailability of essential nutrients69. Therefore, analyzing wastewater before its mixing with source water bodies and soil to avoid further contamination of soil and water resources is necessary.

Conclusion

The feasibility of aquaculture wastewater for irrigating date palm orchards in Saudi Arabia was assessed in this study. Wastewater, pond water, and source water samples were collected from 12 aquaculture farms and analyzed. The results showed that aquaculture wastewater was rich in macronutrients like P, K, NO3−–N, and NH4+–N, as well as micronutrients including Cu, Fe, Zn, and Mn. Irrigation with aquaculture wastewater improved soil quality, increasing the availability of nutrients (P by 49.31%, K by 21.11%, NO3−–N by 33.62%, and NH4+–N by 52.31%). Aquaculture wastewater irrigation also boosted date palm productivity, resulting in 26% higher fruit fresh weight, 23% greater fruit length, 20% more fruit diameter, and 43% higher moisture content compared to source water irrigation, on average basis. Aquaculture wastewater irrigation did not pose any salinity, sodicity, or alkalinity hazards for soil. These findings demonstrate that aquaculture wastewater could be an effective and sustainable irrigation source for date palm orchards in Saudi Arabia. Aquaculture wastewater irrigation can improve soil health, nutrient availability, and date palm growth and yield, while also providing a beneficial reuse pathway for aquaculture effluents. Overall, this study highlights the potential for reusing aquaculture wastewater in agricultural sector to support sustainable crop production.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are not available in the public domain due to privacy and ethical restrictions, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Keating, B. A., Herrero, M., Carberry, P. S., Gardner, J. & Cole, M. B. Food wedges: Framing the global food demand and supply challenge towards 2050. Glob. Food Sec. 3(3–4), 125–132 (2014).

Bos, M. G., Burton, M. A. & Molden, D. J. Irrigation and drainage performance assessment practical guidelines (CABI, Wallingford, 2005).

Ammar, K. A., Kheir, A. M., Ali, B. M., Sundarakani, B. & Manikas, I. Developing an analytical framework for estimating food security indicators in the United Arab Emirates: A review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26(3), 5689–5708 (2024).

Haque, M. I. & Khan, M. R. Impact of climate change on food security in Saudi Arabia: A roadmap to agriculture-water sustainability. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 12(1), 1–18 (2022).

Alotaibi, B. A., Baig, M. B., Najim, M. M., Shah, A. A. & Alamri, Y. A. Water scarcity management to ensure food scarcity through sustainable water resources management in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 15(13), 10648 (2023).

Mallick, J., Singh, C. K., AlMesfer, M. K., Singh, V. P. & Alsubih, M. Groundwater quality studies in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Prevalent research and management dimensions. Water 13(9), 1266 (2021).

El-Juhany, L. I. Degradation of date palm trees and date production in Arab countries: Causes and potential rehabilitation. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 4(8), 3998–4010 (2010).

Almutawa, A. A. Date production in the Al-Hassa region, Saudi Arabia in the face of climate change. J. Water Clim. Change 13(7), 2627–2647 (2022).

Chandrasekharam, D. Water for the millions: Focus Saudi Arabia. Water-Energy Nexus 1(2), 142–144 (2018).

Malibari, R. et al. Reuse of shrimp farm wastewater as growth medium for marine microalgae isolated from Red Sea-Jeddah. J. Clean. Prod. 198, 160–169 (2018).

Al-Shayaa, M. S., Baig, M. B. & Straquadine, G. S. Agricultural extension in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Difficult present and demanding future. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 22(1), 239–246 (2012).

Abd-Elhamid, H. F. et al. Investigating and managing the impact of using untreated wastewater for irrigation on the groundwater quality in arid and semi-arid regions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(14), 7485 (2021).

Ertek, A. & Yilmaz, H. The agricultural perspective on water conservation in Turkey. Agric. Water Manag. 143, 151–158 (2014).

Saikia, D. K., Chikkaputtaiah, C. & Velmurugan, N. Nutritional enrichment of fruit peel wastes using lipid accumulating Aurantiochytrium strain as feed for aquaculture in the North-East Region of India. Environ. Technol. 45, 1212–1233 (2022).

Li, S., Mubashar, M., Qin, Y., Nie, X. & Zhang, X. Aquaculture waste nutrients removal using microalgae with floating permeable nutrient uptake system (FPNUS). Bioresour. Technol. 347, 126338 (2022).

Meneses, M., Pasqualino, J. C. & Castells, F. Environmental assessment of urban wastewater reuse: Treatment alternatives and applications. Chemosphere 81(2), 266–272 (2010).

Ganjegunte, G., Ulery, A., Niu, G. & Wu, Y. Treated urban wastewater irrigation effects on bioenergy sorghum biomass, quality, and soil salinity in an arid environment. Land Degrad. & Develop. 29(3), 534–542 (2018).

Muyen, Z., Moore, G. A. & Wrigley, R. J. Soil salinity and sodicity effects of wastewater irrigation in South East Australia. Agric. Water Manag. 99(1), 33–41 (2011).

Wafula, D. et al. Impacts of long-term irrigation of domestic treated wastewater on soil biogeochemistry and bacterial community structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81(20), 7143–7158 (2015).

Tillman, R. W. & Surapaneni, A. Some soil-related issues in the disposal of effluent on land. Aust. J. Exp. Agri. 42(3), 225–235 (2002).

Leal, R. M. P. et al. Sodicity and salinity in a Brazilian Oxisol cultivated with sugarcane irrigated with wastewater. Agric. Water Manag. 96(2), 307–316 (2009).

Wang, M., Chen, S., Chen, L., Wang, D. & Zhao, C. The responses of a soil bacterial community under saline stress are associated with Cd availability in long-term wastewater-irrigated field soil. Chemosphere 236, 124372 (2019).

Saha, S., Hazra, G. C., Saha, B. & Mandal, B. Assessment of heavy metals contamination in different crops grown in long-term sewage-irrigated areas of Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Environ. Monitor. Assess. 187, 1–12 (2015).

McIntosh, D. & Fitzsimmons, K. Characterization of effluent from an inland, low-salinity shrimp farm: What contribution could this water make if used for irrigation. Aquac. Eng. 27(2), 147–156 (2003).

Abdul-Rahman, S. et al. Improving water use efficiency in semi-arid regions through integrated aquaculture/agriculture. J. Appl. Aquac. 23(3), 212–230 (2011).

KaabOmeir, M., Jafari, A., Shirmardi, M. & Roosta, H. Effects of irrigation with fish farm effluent on the nutrient content of Basil and Purslane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 90(4), 825–831 (2020).

Carey, R. O. & Migliaccio, K. W. Contribution of wastewater treatment plant effluents to nutrient dynamics in aquatic systems: A review. Environ. Manag. 44, 205–217 (2009).

Chávez-Crooker, P. & Obreque-Contreras, J. Bioremediation of aquaculture wastes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 21(3), 313–317 (2010).

Iber, B. T. & Kasan, N. A. Recent advances in shrimp aquaculture wastewater management. Heliyon 7(11), 08283 (2021).

Brooks, B. W. & Conkle, J. L. Commentary: Perspectives on aquaculture, urbanization and water quality. Soil Sci. 37, 29–38 (2019).

Walkley, A. J. & Black, I. A. Estimation of soil organic carbon by the chromic acid titration method (1934).

Wolf, B. A comprehensive system of leaf analyses and its use for diagnosing crop nutrient status. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 13(12), 1035–1059 (1982).

Soltanpour, P. N. & Schwab, A. P. A new soil test for simultaneous extraction of macro-and micro-nutrients in alkaline soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 8(3), 195–207 (1977).

Chow, P. S. & Landhäusser, S. M. A method for routine measurements of total sugar and starch content in woody plant tissues. Tree Physiol. 24(10), 1129–1136 (2004).

Steel, R. G. D., Torrie, J. H. & Dickey, D. A. Principles and procedures of statistics: A biometrical approach 3rd edn, 400–428 (McGraw Hill Book Co., 1997).

Ayers, R. S. & Westcot, D. W. Water quality for agriculture (Vol. 29, p. 174). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (1985).

Bauder, T. A., Waskom, R. M., Sutherland, P. L., Davis, J. G., Follett, R. H. & Soltanpour, P. N. Irrigation water quality criteria. Service in action; no. 0.506 (2011).

FAO. Water Quality for Agriculture. Paper No. 29 (Rev. 1) UNESCO, Publication, Rome (1985).

Saha, S., Rajib, R. H. & Kabir, S. IoT based automated fish farm aquaculture monitoring system. In 2018 International Conference on Innovations in Science, Engineering and Technology (ICISET) (pp. 201–206). IEEE (2018).

US Salinity Laboratory Diagnosis and improvement of saline and alkali soils, Department of Agriculture, U.S. Handbook 60, Washington DC (1954).

FAO 2013. Fish Stat J, a tool for fishery statistics analysis; Release: 2.0.0. http://www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/software/fishstatj/en (2013).

Department of Environment and Conservation NSW. Environmental; guidelines, use of effluent by irrigation. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/water/effguide.pdf (2003).

ANZECC and ARMCANZ (Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council and Agriculture and Resource Management Council of Australia and New Zealand) National water quality management strategy, Australian and New Zealand guidelines for fresh and marine water quality. ANZECC & ARMCANZ, Canberra (2000).

Zou, Y. et al. Effects of pH on nitrogen transformations in media-based aquaponics. Bioresour. Technol. 210(3), 81–87 (2016).

Esteves, A. F., Soares, S. M., Salgado, E. M., Boaventura, R. A. & Pires, J. C. Microalgal growth in aquaculture effluent: Coupling biomass valorisation with nutrients removal. Appl. Sci. 12(24), 12608 (2022).

Ornamental Aquatic Trade Association (OATA), Water Quality Criteria-ornamental fish Company Limited by Guarantee and Registered in England No 2738119 Registere Office Wessex House, 40 Station Road, Westbury, Wiltshire, BA13 3JN, UK, Version 2.0 March, info@ornamentalfish.org. www.ornamentalfish.org (2008).

Stone, N. M. & Thomforde, H. K. Understanding your fish pond water analysis report (pp. 1–4). Cooperative Extension Program, University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, US Department of Agriculture and county governments cooperating (2004).

Rusan, M. J. M., Hinnawi, S. & Rousan, L. Long term effect of wastewater irrigation of forage crops on soil and plant quality parameters. Desalination 215(1–3), 143–152 (2007).

Urbano, V. R., Mendonça, T. G., Bastos, R. G. & Souza, C. F. Effects of treated wastewater irrigation on soil properties and lettuce yield. Agric. Water Manag. 181, 108–115 (2017).

Félix-Cuencas, L. et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus flux in wastewater from three productive stages in a hyperintensive tilapia culture. J. Water Reuse Desalin. 11(3), 520–530 (2021).

Guldhe, A., Ansari, F. A., Singh, P. & Bux, F. Heterotrophic cultivation of microalgae using aquaculture wastewater: A bio refinery concept for biomass production and nutrient remediation. Ecol. Eng. 99, 47–53 (2017).

Tasung, A. et al. Aquaculture effluent: Effect on yield, nutrient content and uptake in Salicornia brachiata Roxb. Environ. Pollut. 2, 5 (2015).

Bowley, D. G. & Allan, G. L. Nutrients in pond based aquaculture discharge water used for irrigation. NSW Department of Primary Industries, Port Stephen Fisheries Institute (2011).

FAO. Prognosis of salinity and alkalinity. FAO Soils Bulletin 31. FAO, Rome (1976).

Wang, Y. B., Xu, Z. R. & Guo, B. L. The danger and renovation of the deteriorating pond sediment. Feed Ind. 26(4), 47–49 (2005).

Cao, L. et al. Environmental impact of aquaculture and countermeasures to aquaculture pollution in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 14, 452–462 (2007).

Davy, J., Becchetti, T., Lile, D., Fulton, A. & Giraud, D. Establishing and managing irrigated pasture for horses, primary plant nutrients: Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (University of Calfornia, 2012).

Griffin, G., Jokela, W., Ross, D., Pettinelli, D., Morris, T. & Wilf, A. Recommended soil nitrate-N tests. Recommended soil testing procedures for the Northeastern United States, (493) (1995).

Akindele, A. J., Olufayo, A. A. & Faloye, O. T. Influence of borehole and fish wastewater on soil properties, productivity and nutrient composition of sweet pepper (Capsicum annum). Acta Ecol. Sin. 42(1), 56–62 (2022).

Sun, H. et al. Spatial variation of soil properties impacted by aquaculture effluent in a small-scale mangrove. Marine Pollut. Bull. 160, 111511 (2020).

Sultana, N., Sarker, M. J. & Palash, M. A. U. A study on the determination of heavy metals in freshwater aquaculture ponds of Mymensingh. Bangladesh Med. J. 3(1), 143–149 (2017).

Keraita, B., Jiménez, B. & Drechsel, P. Extent and implications of agricultural reuse of untreated, partly treated and diluted wastewater in developing countries. CABI Reviews, p. 15 (2008).

Danaher, J. J. Phytoremediation of aquaculture effluent using integrated aquaculture production systems (Doctoral dissertation, Auburn University) (2013).

Delaide, B., Goddek, S., Gott, J., Soyeurt, H. & Jijakli, M. H. Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. Sucrine) growth performance in complemented aquaponic solution outperforms hydroponics. Water 8(10), 467 (2016).

Bitar, D. A., Abu-Quod, H., Isaid, H. M., Daiq, I. H. A., Aref Aslan, K. W. & Alzuhoor, Z. H. The Effect of Irrigation with Fish and Dairy Farm Effluents on the Production of Date Palm cv. Medjool. Pales. J. Technol. Appl. Sci. (6) (2023).

Galal, H. A. Long-term effect of mixed wastewater irrigation on soil properties, fruit quality and heavy metal contamination of citrus. Am. J. Environ. Prot. 3, 100–105 (2015).

Ofori, S., Puškáčová, A., Růžičková, I. & Wanner, J. Treated wastewater reuse for irrigation: Pros and cons. Sci. Total Environ. 760, 144026 (2021).

Adhikari, S., Ghosh, L., Rai, S. P. & Ayyappan, S. Metal concentrations in water, sediment, and fish from sewage-fed aquaculture ponds of Kolkata, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 159(1), 217–230 (2009).

Das, S. S., Hossain, K. M., Mustafa, M. G., Parvin, A. & Saha, B. Physicochemical properties of water and heavy metals concentration of sediments, feeds and various farmed Tilapia (Oreochoromis niloticus). Bangladesh. Fish Aqua. J. 8, 232 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputy of Agriculture at the Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture, Saudi Arabia for supporting this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Funding acquisition, conceptualization, methodology, writing, reviewing, and editing–M.I.A.-W. and M.M.A.-M.; formal analysis, statistical analysis, writing original draft preparation–M.A.; software, data curation, formal analyses, visualization–H.A.A.-S. and J.A.; supervision, writing, reviewing, and editing–A.S.A.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Wabel, M.I., Almutari, M.M., Ahmad, M. et al. Impacts of aquaculture wastewater irrigation on soil health, nutrient availability, and date palm fruit quality. Sci Rep 14, 18634 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68774-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68774-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Irrigation water requirements of date palms in the Arab region: influencing factors, climate change effect, and sustainable irrigation practices

Euro-Mediterranean Journal for Environmental Integration (2026)

-

Comparative analysis of plant morphometric traits, essential oil yield, and quality of Origanum majorana L. cultivated under diverse sustainable organic nutrient management strategies

Scientific Reports (2025)