Abstract

Presbycusis, or age-related hearing loss, affects both elderly humans and dogs, significantly impairing their social interactions and cognition. In humans, presbycusis involves changes in peripheral and central auditory systems, with central changes potentially occurring independently. While peripheral presbycusis in dogs is well-documented, research on central changes remains limited. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a useful tool for detecting and quantifying cerebral white matter abnormalities. This study used DTI to explore the central auditory pathway of senior dogs, aiming to enhance our understanding of canine presbycusis. Dogs beyond 75% of their expected lifespan were recruited and screened with brainstem auditory evoked response testing to select dogs without severe peripheral hearing loss. Sixteen dogs meeting the criteria were scanned using a 3 T magnetic resonance scanner. Tract-based spatial statistics was used to analyze the central auditory pathways. A significant negative correlation between fractional lifespan and fractional anisotropy was found in the acoustic radiation, suggesting age-related white matter changes in the central auditory system. These changes, observed in dogs without severe peripheral hearing loss, may contribute to central presbycusis development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Presbycusis, or age-related hearing loss, is a common condition among the elderly affecting approximately one-third of individuals aged 65–74 and nearly half of those over 751. This condition significantly impacts public health, as it not only impairs effective communication but is also linked with social isolation and accelerated cognitive decline2,3. In humans, presbycusis typically manifests as reduced sensitivity to high-pitched sounds, difficulty understanding speech in noisy environments, and impaired sound localization4,5. Traditionally, primary histological changes contributing to presbycusis were thought to involve peripheral hearing structures, such as hair cell loss, strial atrophy, and basilar membrane thickening6,7,8,9,10,11. However, clinical observations such as speech recognition difficulties are not fully explained by peripheral hearing loss, suggesting that alterations in the central hearing system may also play a role. Advanced imaging techniques like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) have revealed age-related atrophy in the auditory cortex and changes in the white matter of central auditory pathways12,13,14.

Recent human studies using functional auditory tests have revealed that age-associated decline in central auditory function is independent of peripheral auditory function. Bao et al. observed a significant age-related increase in gap detection thresholds, a measure of central auditory temporal processing function, which was not correlated with peripheral hearing function as measured by pure-tone audiometry. Such observation suggests that central auditory function deterioration is not directly linked to the degree of peripheral hearing loss15. Similarly, Purner et al. found that an individual's capacity to discriminate sound duration and decibel level, aspects of central auditory function, deteriorate with age independently of peripheral hearing loss5. Further evidence comes from a study by Qian et al.16. Their study, focusing on adults with normal peripheral hearing, showed age-related increases in gap detection thresholds, particularly in the high-frequency range. This study also noted a decrease in speech recognition in noisy environments as age advances, with the most significant decline occurring after the age of 40. These findings collectively underscore an age-related decline in the central auditory function, suggesting that central presbycusis develops independently and possibly precedes noticeable peripheral hearing loss in people.

Peripheral presbycusis has been reported in dogs, beginning around 8–10 years of age. Similar to humans, histological changes reported in dogs involve the organ of Corti, stria vascularis, and basilar membrane17. Auditory impairment in dogs is most pronounced at middle to high-frequency ranges and adversely affects cognitive function18,19, further aligning with findings in humans. Yet, the concept of central presbycusis in dogs still needs to be explored. This knowledge gap is particularly significant given the similarities between human and canine auditory systems and the understanding of presbycusis thus far. This study aimed to evaluate age-related changes in the central hearing pathway in senior dogs using MRI by measuring DTI scalars. We hypothesized that DTI scalar changes in the central hearing pathway occurred in senior dogs without severe peripheral hearing loss defined as detectable BAER waveforms at 70 dB nHL or less.

Results

Twenty dogs with a fractional life span (FLS) of 0.75 or greater (defined as senior) were initially recruited and underwent hearing testing using brainstem auditory evoked responses (BAER). Anxiolytic or sedative medication was required in 10 dogs to complete the BAER test. Nine dogs received trazodone PO (median dosage 4 mg/kg, range 1.3–6.2 mg/kg), and one dog received 3 ug/kg dexmedetomidine IV. Dogs were categorized as hearing at 50, 70 or 90 decibels (dB nHL) if they had at minimum a wave V on their BAER trace at the dB nHL level being tested. Four dogs were excluded due to severe hearing loss (no detectable waveforms at 70 dB nHL). Evidence of hearing was detected at 70 dB nHL in sixteen dogs, of which six also had a response at 50 dB nHL. These 16 dogs met the criteria for the MRI study.

The dogs who underwent MRI included 5 neutered males and 11 spayed females. Breeds included: American Staffordshire terrier (n = 3), Labrador retriever (n = 3), golden retriever (n = 2), Siberian husky (n = 1), Jack Russell terrier (n = 1), German shorthaired pointer (n = 1), American foxhound (n = 1), boxer (n = 1), and mixed breed (n = 3). The median weight was 25.9 kg (range 8.4–34.0 kg). The median chronological age was 11.95 years (range 10.9–15.6 years), and the median FLS was 1.012 (range 0.85–1.16). Owner feedback on the hearing status of these 16 dogs, obtained prior to the disclosure of BAER result, revealed that 6 owners suspected hearing loss, 9 reported normal hearing, and one did not respond. All demographic information, hearing status and MRI findings are summarized in Table 1.

Brain MRIs were essentially normal structurally, with no evidence of intracranial neoplasia in any of the dogs. Four dogs had a total of 11 cerebral microhemorrhages, including 5 in the caudate nucleus, one in the olfactory bulb, one in the sensorimotor cortex, one in the cingulate gyrus, one in the subcallosal gyrus, and two in the occipital cortex (Fig. 1). The presence of cortical atrophy was assessed by measurement of the interthalamic adhesion20 (Figs. 2 and 3). The median interthalamic adhesion height was 7.00 mm (range 3.46–7.95 mm). Cortical atrophy was observed in two dogs with interthalamic adhesion heights of 3.46 mm and 3.64 mm, respectively. We traced streamlines connecting the established auditory structures to identify the central auditory pathway21,22. This pathway began from the caudal colliculus, continued craniolaterally to the medial geniculate nucleus, and ascended dorsolaterally via the internal capsule to the middle ectosylvian cortex at the temporal lobe (Fig. 4). This pathway was used as the region of interest (ROI) in the ROI-restricted Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS) to analyze the DTI data, including fractional anisotropy (FA), radial diffusivity (RD), axial diffusivity (AD), and mean diffusivity (MD)23,24,25.

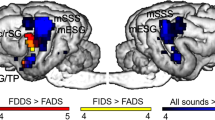

TBSS analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between FA and FLS within the acoustic radiation bilaterally, but more predominantly in the right hemisphere (Fig. 5). However, no significant correlations were found between FLS and the other DTI scalars (RD, AD, and MD), nor between chronological age and DTI scalars. A comparison of DTI scalars between dogs with a BAER threshold of 50 dB nHL (n = 6) and those with a threshold of 70 dB nHL (n = 10) showed no significant differences. Similarly, when dogs were categorized based on owner suspicion of hearing loss (n = 6) versus no suspicion (n = 9), no significant differences in DTI scalars were observed. When dogs were grouped in this way, based on BAER threshold and on owner suspicion of hearing loss, there were no significant differences in age or FLS across groups (Table 2).

Heatmap visualization of TBSS results overlaid on a brain atlas. This heatmap highlights voxels with a significant negative correlation between FA and FLS. The color gradient from red to white reflects a spectrum of FWE-corrected p values. The green regions correspond to the ectosylvian cortex, the purple regions correspond to the medial geniculate nucleus, and the blue regions correspond to the caudal colliculus.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate age-related changes in the central auditory pathways of dogs who had intact peripheral hearing based on BAER testing. We mapped the central auditory pathways using whole brain tractography and connectome matrix. We used voxel-wise analysis to measure the association of DTI scalars to fractional lifespan and chronological age, alongside the difference of DTI scalars between dogs with different BAER thresholds and owner assessment of dog’s hearing capabilities. Our findings revealed a significant decline in FA with increasing FLS in the central auditory pathway bilaterally, but particularly in the right acoustic radiation. This result suggests that as dogs age, microstructural changes in the white matter of the central hearing pathway occur, even in the absence of severe peripheral hearing loss. The age-related changes identified in our study correlate more closely with the life stage, as denoted by FLS, rather than the chronological age in years. This suggests that the white matter changes align more closely with the stage of life based on the expected lifespan than with simple chronological aging.

Diffusion Tensor Imaging is a widely used technique to characterize white matter organization and integrity in vivo. This technique is based on the principles of diffusion-weighted imaging, which measures the direction and extent of water molecule movements in nerve tissue. Cellular structures constrain water molecules within axons and tend to move parallel to the orientation of the axons. Thus, changes in water diffusivity can reflect underlying pathologies in axonal structure and can be quantified through multiple DTI scalars, such as FA, RD, MD, and AD. AD primarily reflects diffusivity along the axial direction, closely associated with axonal injury, while RD measures diffusivity along the radial direction, indicative of demyelination23,24. MD represents average diffusivity in all directions, typically linked with edema25. FA encompasses diffusivity along both axial and radial directions, making it sensitive to a range of microstructural changes in white matter, including axonal injury, demyelination, or combination26. Therefore, FA is considered a sensitive indicator for the directional coherence of white matter tracts, even though it does not specify particular pathologies.

Our results show a decrease in FA within the central auditory pathway as dogs age, particularly in the acoustic radiation. This aligns with a previous canine study, which demonstrated a widespread decrease in FA in the white matter of senior dogs, indicating age-related changes in the white matter structure27. We specifically focused on changes in the central auditory pathway, as these alterations could potentially contribute to presbycusis in dogs. Our findings suggest notable age-related white matter pathologies, including axonal loss, demyelination, or a combination, which could disrupt signal transmission from the medial geniculate nucleus to the auditory cortex, thereby impacting sound perception and contributing to presbycusis in dogs. The fact that FA is sensitive but not specific to certain types of pathologies may suggest that the pathology affecting the auditory pathway in dogs can be attributed to a combination of both axonal loss and demyelination without the predominance of either pathology. This explanation may account for the absence of correlation with other DTI scalars which are more specific to certain pathologies. The interpretation of DTI scalars, however, is complex and can be influenced by a variety of elements, including imaging noise, effects of partial volume, and the presence of crossing fibers25,28. Therefore, further histological investigations are necessary, particularly focusing on acoustic radiation, to deepen our understanding of central presbycusis in dogs.

The DTI scalars did not reveal significant structural differences between the two BAER categories. Although no similar canine study has been conducted yet, some human studies have suggested that central auditory function can deteriorate independently of peripheral auditory function5,15,16. Therefore, different BAER categories might not necessarily show structural differences in the central auditory system, or our small group size meant we did not have enough statistical power. We anticipated potential differences in DTI scalars based on owner suspicion of hearing loss, as owners might notice changes in their pet’s response to sounds, involving sound processing and perception in the central auditory system. However, this suspicion was based on a simple yes or no question without detailed reporting. Numerous environmental and behavioral factors could affect a dog's response to sound. This finding underscores a more comprehensive owner survey is needed to accurately capture these observations, and once again, a larger sample size would have been more powerful.

The question of whether the aging process of particular tissues reflects a physiological aging rate linked to lifespan, or to the number of years that have passed is of great interest29. This question can be studied in dogs because their expected lifespan varies widely between breeds and is linked to weight and height, thus allowing calculation of expected lifespan and expression of stage of life as a proportion of this lifespan (fractional lifespan, FLS)30. Our findings of correlation between FA and FLS but not chronological age suggest aging of white matter is linked to the physiological aging rate that dictates expected lifespan rather than chronological age. Conversely, a previous study using owner-performed cognitive testing found that chronological age had a greater impact on cognitive function than life stage29. Given these white matter changes are evident before severe hearing loss becomes detectable, this might reflect a disconnect between white matter imaging changes that are caused by changes in myelination and ultimate loss of auditory function due to neuronal loss, underscoring the need for further research on central auditory function in senior dogs. In veterinary audiology, the assessment of the central auditory function is neglected. The primary method for assessing canine hearing is the BAER, which effectively evaluates auditory pathways up to the caudal colliculus. However, this electrodiagnostic test faces challenges in assessing middle and late latency responses, which are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of higher auditory pathways. Unlike in human audiology, where a variety of functional auditory tests provide essential insights into central auditory functions, such equivalent tools are not readily available in veterinary settings. In human audiology, these tests include dichotic listening, binaural interaction tasks, monaural low-redundancy tests, and temporal processing tests. Temporal processing tests are considered the most sensitive in assessing the integrity of the central auditory system, evaluating an individual's capacity to perceive and interpret auditory information over time, and covering aspects like gap detection, pattern recognition, and temporal integration31. These tests are extensively applied in studying central auditory function and diagnosing central presbycusis in humans. The progress in human audiology highlights the necessity for the development of comparable functional auditory tests in veterinary medicine. Such advancements would considerably improve our understanding of the central auditory system in dogs, thereby addressing the existing knowledge gap regarding central presbycusis in dogs.

In this study, we observed significant changes bilaterally but more prominently in the right hemisphere, similar to the findings of Ma et al., who noted a reduction in FA near the right auditory regions in human presbycusis patients13. A loss of high-pitch sound perception often marks presbycusis in humans, a function typically associated with the right hemisphere32. This parallel suggests the possibility of similar auditory changes in dogs, specifically in the context of presbycusis. While there is no direct research on lateralized hemispheric functions for pitch perception in dogs, cerebral lateralization at various functional levels, including motor and sensory functions, has been extensively studied in dogs33,34,35,36,37. A study conducted by Siniscalchi et al. reported a functional dichotomy between the hemispheres of dogs. They found the left hemisphere of dogs primarily processes familiar sounds and species-specific vocalizations. In contrast, the right hemisphere is predominantly involved in processing unfamiliar and emotionally charged sounds, such as the sound from a thunderstorm38. This observation highlights the specialized role each hemisphere serves in auditory processing in dogs.

This study has several limitations that should be noted. First, the inclusion of only sixteen dogs with a limited age range may only partially capture the association between all DTI scalars and age. A more extensive population size and a more comprehensive study design, either group-wise or longitudinal, could provide a more detailed understanding of age effects. Second, while DTI is a sensitive and widely utilized technique for detecting microstructural changes in white matter, confirmation of specific pathologies in the auditory pathway requires histopathological examination. Third, our methodology focused exclusively on streamlines connecting established auditory structures, but without a corresponding histological comparison, it is challenging to assess the robustness of the tractography results. Our study did not address gray matter changes, instead focusing on white matter using DTI, but a gray matter morphometry study would be of great interest in this population of dogs. Finally, the lack of established functional auditory tests for dogs limits our ability to correlate these structural changes with actual clinical outcomes or auditory performance in dogs.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated age-related changes in the central auditory pathways of dogs, revealing a decrease in FA in the acoustic radiation as dogs age. These findings suggest microstructural alterations in the white matter that could precede severe peripheral hearing loss, contributing to our understanding of canine presbycusis. Our findings also highlight the need for further research on the development of functional auditory tests in dogs.

Methods

Ethics declarations

This study was conducted and reported according to the ARRIVE guidelines. Protocols underwent review and approval by the North Carolina State University Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee (IACUC # 21-303-O). All procedures were performed in accordance with these approved protocols and institutional guidelines. Owners of the dogs who participated in these studies reviewed and signed an informed consent form. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was not sought because all collected data pertained to dogs, and as such, the work was categorized as “Non-Human Subject Research”.

Study population

This study, conducted at North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine (NCSU CVM), prospectively enrolled companion dogs. Recruitment focused on local community owners and NCSU CVM staff through emails and postings on the NCSU CVM clinical trials website from November 1st 2020 through October 31st 2023.

To be included, dogs were required to have a FLS equal to or greater than 0.75, indicating an age surpassing 75% of their anticipated lifespan. The expected lifespan for each dog was determined using the formula proposed by Greer et al., which incorporates their height and weight30. The FLS was calculated by dividing the chronological age of the dog by its expected lifespan. This decision was based on the definition of life stages in dogs in which dogs that are greater than 75% of their expected lifespan are classified as senior39. To qualify for participation, dogs also needed to be healthy enough to undergo anesthesia without undue risk, and the owner agreed to let them undergo an MRI scan after being informed of related risks. If diagnosed with congenital or acquired deafness prior to reaching 75% of their expected lifespan, the dogs were excluded.

Hearing assessments

To identify dogs before the onset of significant hearing loss, we conducted BAER assessments following the protocol outlined by Fefer et al.19. If needed, dogs were given oral trazodone (1–7 mg/kg, Pliva, Zagreb, Croatia) or intravenous dexmedetomidine (3 ug/kg, Zoetis, Michigan, USA) prior to BAER testing. Electrodes were placed subcutaneously with the recording electrode at the vertex, the ground electrode dorsal to the first cervical vertebra and reference electrodes over the mastoid process bilaterally. Tubal inserts with foam tips were placed in the external ear canals. Monaural click stimuli at 70 dB nHL were used, delivered at 11.4 Hz with alternating polarity. The average response to 1000 clicks was recorded. A masking noise at 40 dB nHL was applied to the non-stimulated ear. If a distinct wave V was detected during the examination of either ear, the stimulus intensity was reduced to 50 dB nHL, and the test was repeated. In the absence of waveforms at 70 dB nHL, the stimulus intensity was increased to 90 dB nHL, and testing was repeated. Dogs who demonstrated a distinct wave V at either 70 dB nHL or 50 dB nHL, subsequently underwent MR imaging. Dogs with no detectable waveforms at 70 dB nHL were excluded due to severe hearing loss. Prior to disclosing the BAER outcomes and proceeding with MRI, owners of the eligible dogs were questioned about any suspicions of hearing impairments in their dogs, recording a simple “yes” or “no”.

MRI

The dogs underwent general anesthesia performed by a board-certified veterinary anesthesiologist. Anesthesia protocol was determined by the anesthesiologist for each patient, drugs used to premedicate, induce and maintain anesthesia are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, end-tidal carbon dioxide level, and electrocardiogram were monitored during the anesthesia. MRI was performed in a 3.0 T Siemens MAGNETOM Skyra (Siemens, Cary, NC) with a 15-channel knee coil receiver. All dogs were positioned in sternal recumbency. A 3D T1 magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) image was acquired through the following protocol: slice thickness of 0.5 mm, voxel size of 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm, repetition time of 2300 ms, echo time of 3.68 ms, and flip angle of 9°. Other conventional MRI sequences including T2 weighted sagittal, T2 weighted transverse, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery transverse, and susceptibility—weighted transverse images were also acquired. Imaging parameters for the conventional MRI are outlined in the Supplementary Table 2.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) scans were acquired in the transverse plane using a bipolar diffusion encoding scheme and the following imaging protocol: slice thickness of 1.5 mm, voxel size of 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm, 64 gradient directions, b-value of 800 s/mm2, repetition time of 9300 ms, and echo time of: 91 ms. All brain MRI scans were reviewed by two board-certified veterinary neurologists (NZ, NJO). Dogs with intracranial neoplasia were excluded. Brain atrophy was assessed by NZ by measuring the interthalamic adhesion height as described previously in order to assess the degree of age-associated cerebral atrophy20. Microhemorrhages are a common finding in the aging dog brain and could potentially affect the auditory pathway. They were identified based on the presence of round or oval-shaped signal voids within the cerebral parenchyma with maximal diameter ≤ 5.7 mm on transverse susceptibility-weighted imaging40,41,42.

Data processing

Raw diffusion DICOM data were converted to NIfTI format using dcm2niix43. DWI data were processed via FSL (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/) and MRtrix3 (https://www.mrtrix.org) software. DWI preprocessing includes denoising44, Gibbs artifact removal45, eddy-current and motion correction46, and bias field correction47. Diffusion tensor scalar maps, including FA, RD, AD, and MD were generated through dwi2tensor and tensor2metric48. Modified TBSS analysis was conducted following a canine study reported by Barry et al.27. tbss_1_preproc was used to perform image erosion and remove zero-end slices, improving data quality and alignment. Using the − n flag of tbss_2_reg, nonlinear registration was performed to align each FA map to another. Based on the result of the last step, tbss_3_postreg with − S flag was used to identify the most representative subject of the group as the template space. The individual FA maps were then registered to the template space, averaged, and subjected to a threshold at 0.2 to create an FA skeleton. Individual FA data was projected onto the FA skeleton using tbss_4_prestats to generate a 4D skeletonized file for statistical analysis49. MD, AD, and RD were projected similarly based on the FA skeleton.

Region of interest (ROI)

The streamlines connecting the caudal colliculus, medial geniculate nucleus and middle ectosylvian cortex were selected as the ROI. We first computed the response functions for white matter, gray matter, and CSF using the dhollander algorithm in the dwi2response50 and then computed voxel-wise fiber orientation distributions (FODs) using dwi2fod51,52. With the FOD data of each individual, whole-brain probabilistic tractography was performed53. A parcellated canine brain atlas54 was registered to each individual’s space to create a connectome matrix using tck2connectome55. Regions of interest include the caudal colliculus, medial geniculate nucleus, and middle ectosylvian cortex. Based on the connectome matrix, the subject with the highest number of anatomically correct streamlines was selected. Using connectome2tck48, streamlines connecting the regions of interest were extracted as a mask in the following analysis.

Statistics

Using the region of interest as a mask, the skeletonized data were analyzed through a non-parametric permutation general linear model (GLM) framework. To comprehensively assess age-related changes, this study utilized two measures of age: chronological age and FLS. Chronological age refers to the actual age of the dogs in years, whereas FLS is calculated based on the expected lifespan of the breed30. This approach provides a relative measure of age that accounts for breed-specific differences in longevity. In the GLM, the FLS or age were designated as the independent variables and diffusion scalars were identified as the dependent variables. The skeletonized data for each individual were categorized according to their BAER category (50 dB nHL vs. 70 dB nHL) and the owner’s suspicion of hearing loss (Yes vs. No). Group comparisons of chronological age and FLS were performed using independent t-test or Wilcoxon 2-sample test based on the data distribution. Comparisons of DTI scalars between groups were conducted within the GLM framework using independent t-test. Multiple comparisons were corrected by threshold-free cluster enhancement and family-wise error correction (FWE). FWE-corrected p < 0.05 was considered significant56,57,58.

Data availability

References

NIDCD. Age-Related Hearing Loss (Presbycusis). https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/age-related-hearing-loss (National Institutes of Health, 2023).

Lin, F. R. et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 173, 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868 (2013).

Lin, F. R. et al. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch. Neurol. 68, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2010.362 (2011).

Gates, G. A. & Mills, J. H. Presbycusis. Lancet 366, 1111–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67423-5 (2005).

Purner, D., Schirkonyer, V. & Janssen, T. Changes in the peripheral and central auditory performance in the elderly—A cross-sectional study. J. Neurosci. Res. 100, 1791–1811. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.25068 (2022).

Bredberg, G. Cellular pattern and nerve supply of the human organ of Corti. Acta Otolaryngol. 236, 231 (1968).

Johnsson, L. G. & Hawkins, J. E. Jr. Sensory and neural degeneration with aging, as seen in microdissections of the human inner ear. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 81, 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348947208100203 (1972).

Pauler, M., Schuknecht, H. F. & White, J. A. Atrophy of the stria vascularis as a cause of sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope 98, 754–759. https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-198807000-00014 (1988).

Kusunoki, T. & Cureoglu, S. Age-related histopathologic changes in the human cochlea. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 134, 715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2005.10.052 (2006).

Suzuki, T. et al. Age-dependent degeneration of the stria vascularis in human cochleae. Laryngoscope 116, 1846–1850. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000234940.33569.39 (2006).

Huang, Q. & Tang, J. Age-related hearing loss or presbycusis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 267, 1179–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-010-1270-7 (2010).

Profant, O. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging and MR morphometry of the central auditory pathway and auditory cortex in aging. Neuroscience 260, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.010 (2014).

Ma, W. et al. DTI analysis of presbycusis using voxel-based analysis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 37, 2110–2114. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4870 (2016).

Armstrong, N. M. et al. Association of poorer hearing with longitudinal change in cerebral white matter microstructure. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 146, 1035–1042. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2020.2497 (2020).

Bao, J. et al. Evidence for independent peripheral and central age-related hearing impairment. J. Neurosci. Res. 98, 1800–1814. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24639 (2020).

Qian, M. et al. The effects of aging on peripheral and central auditory function in adults with normal hearing. Am. J. Transl. Res. 13, 549–564 (2021).

Shimada, A., Ebisu, M., Morita, T., Takeuchi, T. & Umemura, T. Age-related changes in the cochlea and cochlear nuclei of dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 60, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.60.41 (1998).

Ter Haar, G., Venker-van Haagen, A. J., van den Brom, W. E., van Sluijs, F. J. & Smoorenburg, G. F. Effects of aging on brainstem responses to toneburst auditory stimuli: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 22, 937–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0126.x (2008).

Fefer, G. et al. Relationship between hearing, cognitive function, and quality of life in aging companion dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 36, 1708–1718. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.16510 (2022).

Hasegawa, D., Yayoshi, N., Fujita, Y., Fujita, M. & Orima, H. Measurement of interthalamic adhesion thickness as a criteria for brain atrophy in dogs with and without cognitive dysfunction (dementia). Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 46, 452–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8261.2005.00083.x (2005).

de Lahunta, A., Glass, E. & Kent, M. In de Lahunta’s Veterinary Neuroanatomy and Clinical Neurology 5th edn (eds de Lahunta, A. et al.) 457–464 (W.B. Saunders, 2021).

Uemura, E. E. In Fundamentals of Canine Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology (ed. Uemura, E. E.) 329–346 (Wiley, 2015).

Song, S. K. et al. Dysmyelination revealed through MRI as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. Neuroimage 17, 1429–1436. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2002.1267 (2002).

Song, S. K. et al. Demyelination increases radial diffusivity in corpus callosum of mouse brain. Neuroimage 26, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.028 (2005).

Alexander, A. L., Lee, J. E., Lazar, M. & Field, A. S. Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics 4, 316–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011 (2007).

Aung, W. Y., Mar, S. & Benzinger, T. L. Diffusion tensor MRI as a biomarker in axonal and myelin damage. Imaging Med. 5, 427–440. https://doi.org/10.2217/iim.13.49 (2013).

Barry, E. F. et al. Diffusion tensor-based analysis of white matter in the healthy aging canine brain. Neurobiol. Aging 105, 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.04.021 (2021).

Figley, C. R. et al. Potential pitfalls of using fractional anisotropy, axial diffusivity, and radial diffusivity as biomarkers of cerebral white matter microstructure. Front. Neurosci. 15, 799576. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.799576 (2021).

Watowich, M. M. et al. Age influences domestic dog cognitive performance independent of average breed lifespan. Anim. Cogn. 23, 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-020-01385-0 (2020).

Greer, K. A., Canterberry, S. C. & Murphy, K. E. Statistical analysis regarding the effects of height and weight on life span of the domestic dog. Res. Vet. Sci. 82, 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2006.06.005 (2007).

Musiek, F. E. & Chermak, G. D. In HandBook of Clinical Neurology, vol. 129, 313–332 (2015).

Zatorre, R. J., Evans, A. C., Meyer, E. & Gjedde, A. Lateralization of phonetic and pitch discrimination in speech processing. Science 256, 846–849. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1589767 (1992).

Quaranta, A., Siniscalchi, M., Frate, A. & Vallortigara, G. Paw preference in dogs: Relations between lateralised behaviour and immunity. Behav. Brain Res. 153, 521–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2004.01.009 (2004).

Quaranta, A., Siniscalchi, M. & Vallortigara, G. Asymmetric tail-wagging responses by dogs to different emotive stimuli. Curr. Biol. 17, R199-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.008 (2007).

Siniscalchi, M., Sasso, R., Pepe, A. M., Vallortigara, G. & Quaranta, A. Dogs turn left to emotional stimuli. Behav. Brain Res. 208, 516–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.042 (2010).

Siniscalchi, M., d’Ingeo, S. & Quaranta, A. The dog nose “KNOWS” fear: Asymmetric nostril use during sniffing at canine and human emotional stimuli. Behav. Brain Res. 304, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2016.02.011 (2016).

Siniscalchi, M., D’Ingeo, S. & Quaranta, A. Lateralized functions in the dog brain. Symmetry 9, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9050071 (2017).

Siniscalchi, M., Quaranta, A. & Rogers, L. J. Hemispheric specialization in dogs for processing different acoustic stimuli. PLoS ONE 3, e3349. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003349 (2008).

Creevy, K. E. et al. 2019 AAHA canine life stage guidelines. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 55, 267–290. https://doi.org/10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6999 (2019).

Greenberg, S. M. et al. Cerebral microbleeds: A guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 8, 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70013-4 (2009).

Kerwin, S. C., Levine, J. M., Budke, C. M., Griffin, J. F. T. & Boudreau, C. E. Putative cerebral microbleeds in dogs undergoing magnetic resonance imaging of the head: A retrospective study of demographics, clinical associations, and relationship to case outcome. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 31, 1140–1148. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.14730 (2017).

Fulkerson, C. V., Young, B. D., Jackson, N. D., Porter, B. & Levine, J. M. MRI characteristics of cerebral microbleeds in four dogs. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 53, 389–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8261.2011.01910.x (2012).

Li, X., Morgan, P. S., Ashburner, J., Smith, J. & Rorden, C. The first step for neuroimaging data analysis: DICOM to NIfTI conversion. J. Neurosci. Methods 264, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.03.001 (2016).

Veraart, J. et al. Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory. Neuroimage 142, 394–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.016 (2016).

Kellner, E., Dhital, B., Kiselev, V. G. & Reisert, M. Gibbs-ringing artifact removal based on local subvoxel-shifts. Magn. Reson. Med. 76, 1574–1581. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26054 (2016).

Andersson, J. L. R. & Sotiropoulos, S. N. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage 125, 1063–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.019 (2016).

Tustison, N. J. et al. N4ITK: Improved N3 bias correction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 29, 1310–1320. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2010.2046908 (2010).

Tournier, J. D. et al. MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. Neuroimage 202, 116137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116137 (2019).

Smith, S. M. et al. Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 31, 1487–1505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024 (2006).

Dhollander, T., Mito, R., Raffelt, D. & Connelly, A. Improved white matter response function estimation for 3-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution. Proc. Int. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 27, 555 (2019).

Jeurissen, B., Tournier, J. D., Dhollander, T., Connelly, A. & Sijbers, J. Multi-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution for improved analysis of multi-shell diffusion MRI data. Neuroimage 103, 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.07.061 (2014).

Tournier, J. D., Calamante, F., Gadian, D. G. & Connelly, A. Direct estimation of the fiber orientation density function from diffusion-weighted MRI data using spherical deconvolution. Neuroimage 23, 1176–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.037 (2004).

Tournier, J. D., Calamante, F. & Connelly, A. Improved probabilistic streamlines tractography by 2nd order integration over fibre orientation distributions. Proc. Int. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 1670, 88 (2010).

Johnson, P. J. et al. Stereotactic cortical atlas of the domestic canine brain. Sci. Rep. 10, 4781. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61665-0 (2020).

Smith, R. E., Tournier, J. D., Calamante, F. & Connelly, A. The effects of SIFT on the reproducibility and biological accuracy of the structural connectome. Neuroimage 104, 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.10.004 (2015).

Winkler, A. M., Ridgway, G. R., Webster, M. A., Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Permutation inference for the general linear model. Neuroimage 92, 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.060 (2014).

Salimi-Khorshidi, G., Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Adjusting the effect of nonstationarity in cluster-based and TFCE inference. Neuroimage 54, 2006–2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.088 (2011).

Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 44, 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Dr. Kady M. Gjessing and Rhanna M. Davidson Distinguished Chair of Gerontology. We would like to acknowledge Jennifer Massey for MRI acquisition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y., N.J.O., and M.E.G. contributed to the conceptualization of the study. C.Y. and Y.W. were responsible for processing the data. C.Y. conducted the data analysis. Y.W., P.T. and N.J.O. reviewed the methodology. C.Y., N.Z., G.F., and N.C.N. participated in data acquisition. The original draft was prepared by C.Y., P.T., and N.J.O. All authors participated in the final editing and reviewing process of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, CC., Yap, PT., Wu, Y. et al. Voxelwise analysis of the central hearing pathway in senior dogs reveals changes associated with fractional lifespan. Sci Rep 14, 18121 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68828-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68828-3