Abstract

In the present work, a glass system with developed composition consisting of B2O3, ZnO, Na2O and Fe2O3 samples has been investigated. Glass samples were prepared using the melt quenching method and the density of the system was measured using Archimedes’ principle. Spectroscopic analysis using a gamma source and a high-purity germanium detector at four energies of 0.0595, 0.6617, 1.173, and 1.333 MeV emitted from Am-241, Cs-137, and Co-60 were used to determine the attenuation parameters of present glass composites. The sample containing 45 B2O3 + 10 Na2O + 40 ZnO + 5 Fe2O3 (coded BNZF-4) had the highest mass attenuation coefficient (MAC) value at all the energies discussed compared to the other composites. Whoever, the BNZF-1 sample had the lowest value at all ranges of energies. The transmission factors (TF, %) of the manufactured samples were calculated, at 0.0595 MeV (TF, %) values are 32.6429 and 6.4612 for samples BNZF-1 and BNZF-4, respectively. The statistical results demonstrated significantly better to increase the ZnO concentration in the sample, where the percentage of zinc oxide inside the prepared glass samples has the following direction BNZF -4 > BNZF -3 > BNZF -2 > BNZF -1. The significance of this study is that transparent, environmentally harmless glass composites with relatively high density have been prepared that can be used as shielding materials against gamma rays, especially at low energies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Owing to advancements in technology, people are exposed to the risks of ionizing radiation through normal background radioactivity, mining, milling, nuclear power plants that use synthetic radioactive isotopes, space exploration, nuclear research, and other areas. It is crucial to note that radiation exposure can cause a variety of health problems, among the most significant of which include carcinomas, genetic disorders, and tissue damage. It's also crucial to remember that ionizing radiation can alter the physical properties and chemical structure of soil, rock, and water, which can have a negative effect on biodiversity and the ecosystem. This requires careful investigation and effective protection and shielding techniques because they pose significant risks to humans1,2,3.The protection can be attained by using efficient shields, which necessitates researching all aspects of possible shielding substances, including their mechanical attributes, various radiation attenuation features, anticipated energies, expenses and accessibility of substances, no difficulty in manufacturing, performance, and the probability of affordable prices4,5,6.

A crucial characteristic is the degree of resistance of the shielding material against potential harm induced by being exposed to ionizing electromagnetic radiation, together with ensuring that the shields are non-toxic. Along with a large rays-absorption cross-section, the efficient shielding substance must also induce a considerably greater strength attenuation of the incoming rays throughout a narrow penetration depth (thickness)7. Various kinds of substances are frequently employed for this purpose, in accordance with the intended use. For example, because concrete is useful and excellent at attenuating X-rays, it is widely used as the absorber along the exterior walls of X-ray rooms. Concrete may serve as a perfect material in certain situations, but alternative materials are occasionally required because it can crack easily and lose moisture when exposed to radiation for an extended period8,9. Glasses by adding metallic oxides to their formulation, are capable of functioning as radiation shielding materials. Since their high density raises the density of the glass materials, which usually corresponds to higher shielding properties, heavy metal oxides are usually among the most efficient10,11,12,13,14. Moreover, well-known techniques like melt quenching are applicable to create glasses. Because glasses are inexpensive to manufacture, scientists are more inclined to employ them as alternative components for materials that need radiation shielding15.

When manufacturing our glass materials, a few factors will be taken into consideration. These include the need for a large mass density as well as excellent transparency to the visible portion of the electromagnetic range to be able to provide beneficial shielding properties and guarantee a notably significant interaction probability between the glass and photons. Consequently, this elevated contact probability means that the energy of ionizing rays will be much reduced and the rays' capacity to pass through glass will be eliminated15,16. To improve radiation shielding, one of the strategies is to increase the glass density. It was reported that, glasses based on borate have low viscosity, great mechanical strength, short glass transition temperature, high chemical durability, and clear transparency. They are also cost-effective materials. Owing to these characteristics, glasses based on borate have gained attention for a wide range of uses, such as biomedical, shielding, industrial, and several other uses17,18,19. By adding metal oxides as network modifiers such as ZnO, Na2O, Fe2O3, borate glass can be tested for its radiation shielding properties20. Borate-based glasses are gaining a lot of attention as radiation shielding materials and considered a hot topic in the discipline of radiation protection safety. Glasses made of borate could have superior shielding properties as their density could be adjusted. Using heavy-duty rare earth oxides and heavy earth oxide metal oxides in glass samples are a simple way to increase glass density21,22,23.

In this work, our goal was to manufacture non-toxic and cost-effective glass samples of various compositions using a melt quenching procedure (85-x) B2O3 + 10 Na2O + (x)ZnO + 5 Fe2O3, where x = 10, 20, 30 and 40 wt %. It is also an attempt to mitigate the harmful effects of radiation on humans and the environment and ensure the benefit of ionizing radiation in the long term without exposure to serious harm.

Materials and methods

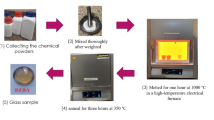

Glass manufacturing

To prepare the glass samples under investigation, some oxides were used, such as ZnO, Na2O, Fe2O3, and B2O3. Four samples of zinc sodium borate glasses were manufactured with different ratios among them as shown in Table.1 and the ratio were variable between B2O3 and ZnO and constant for Na2O, Fe2O3. The samples were Manufactured according to the annealing technique, the material has been mixed perfectly well and conveniently and placed in a crucible of aluminum and then entered an electric oven at a constant temperature of 950 Celsius for a full 60 min. The other stage is to pour the mixture of molten glass into stainless-steel mold and put it in a separate electric oven at a temperature of 300 for almost 180 min to eliminate internal stresses.

The density of each sample is an important parameter in our work. So, to precisely determine the density of the six samples, we used a very simple and correct method of calculating the density of each sample. The following equation, which uses Archimedes’ is used to calculate the density of the manufactured glasses, uses the (Wa) and (WL) values as symbols for the weight of the glasses in liquid and air. Correspondingly, when utilizing water as an immersing liquid, the ρL value represents the density of the immersed liquid, which is taken as 1 g/cm324,25.

Experimental procedures

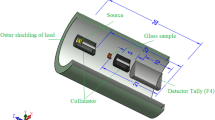

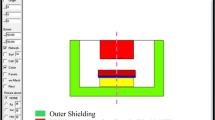

The ionizing γ-ray sources Am-241, Co-60, and Cs-137 were identified using an HPGe (high-purity germanium semiconductor detector) with a 24% relative efficiency in this research. The energy range covered by these sources is 60 to 1333 keV. The glass sample was inserted at an appropriate location between the gamma source and the HPGe, as shown in Fig. 1. It displays the experimental setup diagram of attenuation factor calculations., With a lead collimator positioned between the gamma source and the HPGe-detector, the measurements were carried out using the narrow beam technique. The count rate was measured in the case of the sample (A) and in its absence (A0), and those results were recorded Enabling us to identify linear attenuation coefficient (cm−1) as well as some important parameters in our work26,27,28

where x is the glasses sample thickness, depending on I and Io calculations, the other essential shielding-related parameters, such as the radiation protection efficiency (RPE %), half-value thickness (Δ0.5, cm), and lead's equivalent thickness (Δeq, cm), can be expressed using the following formulae29,30,31.

Result and Discussion:

Table 1 lists the names, densities, and chemical constituents for each chosen glass system. Table 2 shows the results of linear attenuation coefficients, LAC, at certain gamma energies viz., 0.0595, 0.06617, 1.173 and 1.333 MeV acquired with the experimental and theoretical methods. Experiments were performed with the HPGe detector. The renowned XCOM programme was used to confirm the results that were so acquired. The LAC data were also further utilized to compute additional shielding parameters namely mass attenuation coefficient (MAC), half value layer (HVL), mean free path (MFP), tenth value layer (TVL) and radiation protection efficiency (RPE). Additionally, an assessment of the manufactured glass materials’ radiation shielding effectiveness (RSE) and transmission factor (TF %), have been determined.

Table 2 presents the relative deviations of LAC values for glass samples obtained from XCOM programme and experiments. It is seen that the relative differences between the XCOM programme and the LAC values obtained from trials are negligible. For example, the theoretical value of 1.1195 validates the experimental value of 1.0923 for BNZF-1 glass at low energy of 0.05595 MeV. Additionally, the XCOM value of 0.1482 confirms the experimental value of 0.1492 for the same glass system at higher energy (1.333 MeV). For the glass samples under investigation, the range of experimental and theoretical deviations is from −6.67 to 6.09. Figure 2 illustrates how the LAC values of the chosen glass samples varied across the photon energy range of 0.0595 MeV to 1.333 MeV. It is clear from this that LAC is dependent upon the chemical composition of the samples as well as the incoming photon energy. The sample BNZF-4 exhibits higher values of LAC than the others because it has the largest density and greater weight fraction of B2O3 (Table 1). After a steep decline from 0.0595 to 0.6617 MeV, there is a little variation in LAC values. The likelihood of interaction is determined by the atomic number (Zn), where the exponent n fluctuates from 4 to 5, and the dominance of the photoelectric effect at lower energy, in which the interaction cross section depends on energy as σPh ~ E−7/2. At intermediate energies, the Compton effect (σCom ~ E−1) predominates. The attenuation levels at these energies were the same in all samples, as indicated by the LAC values. The reason for this is that Compton scattering has a linear dependence on atomic number, Z32,33.

The mass attenuation coefficient (MAC) quantifies the average number of interactions between light photons and matter in a certain mass per unit area thickness of the substance under investigation33. Figure 3 displays the glasses’ MAC values; the photon energy extends from 0.0595 to 1.333 MeV. It was found that the components of the glasses have a significant impact on MAC values; MAC values behave in line with B2O3 levels. Other constituents Na2O, ZnO and Fe2O3 have same proportions for all the glasses. The MAC is in the following order: BNZF-4 > BNZF-3 > BNZF-2 > BNZF-1. The energy of the incident photons shows a consistent pattern across all glasses in the MACs. For all glasses, MACs show the same trend in the energy of the incident photons, and it has similar behaviour as that of LAC.

The half value layer (HVL), tenth value layer (TVL), and mean free path (MFP) variations as a function of the source photon energy are displayed in Figs. 4,5 and 6. These are important characteristics that provide the necessary material thicknesses at certain energy and the material's ability to shield. These variables exhibit the exact opposite pattern of variation from LAC, that is, a rising tendency with incident energy. The lowest values of these parameters across all samples are found at 0.0595 MeV. At lower energy, these thicknesses fall into the following ranges: 0.253–4.678 cm (HVL); 0.365–6.748 cm (MFP); and 0.841–15.539 cm (TVL). The values of these characteristics were found to increase with the following trend BNZF-4 < BNZF-3 < BNZF-2 < BNZF-1 among the selected samples. This indicates that BNZF-4 is a superior radiation shield among the glasses under investigation. This is explained by the fact that BNZF-4 has the largest density of all the materials under study, which reduces values for HVL, TVL, and MFP and raises the likelihood of interaction. These outcomes are consistent with the earlier research34,35,36.

Figure 7 depicts variation of transmission factor (TF, %) versus energy for 1 cm thickness for the glasses under investigation. The trend of variations in TF levels is comparable to that of energy. TFs have lower values at lower energies and increase with increased photon energy. Sample BNZF-1 has TF of 32.6429 whereas BNZF-4 has TF value 6.4612 at 0.0595 MeV. At higher energy of 1.333 MeV, BNZF-1 and BNZF-4 glasses have TFs 86.2273 and 83.4024 sequentially. The effectiveness of a shielding material is determined by several parameters, one of the crucial parameters is its radiation protection efficiency, RSE (%) of the investigated glasses as a function of energy have been portrayed in Fig. 8 at 1 cm. An inverse relation is clearly observed between energy and RSE33. This declining tendency is brought on by higher energy photons’ greater penetrating power, which lessens ability of these glasses to absorb/block incoming radiation. At 0.0595 MeV, BNZF-1 glass has RSE 67.357% and other glasses have RSE in order of 79–93%. This indicates that the glasses under study are very good at attenuating the lower-energy photons. Among the selected glasses, BNZF-4 glass has shown greatest radiation shielding efficiency.

Conclusion

In the presented investigation a high-purity germanium detector was used for assessing the linear attenuation coefficient of four novel B2O3, ZnO, Na2O, and Fe2O3 glass components coded (BNZF-1 to BNZF-4) at four various energy ranges: Am-241 (0.0595 MeV), tansmetCs-137 (0.6617 MeV), and Co-60 (1.173 and 1.333 MeV). The results indicated that the linear attenuation coefficient values of the glass samples decreased by the following trend BNZF -4 > BNZF -3 > BNZF -2 > BNZF -1. Moreover, the partial density jumped when ZnO concentration grew in relation to B2O3. The manufactured glasses’ density is increased between 2.7677 and 3.4251 g/cm3 when ZnO is substituted for B2O3, with an increase of 10–40 mol% for ZnO. Likewise, the manufactured BNZF glasses’ ability to attenuate gamma radiation is enhanced when ZnO is substituted for B2O3. It is obvious that the glass components have a significant impact on the mass attenuation coefficient MAC values; MAC values behave in line with ZnO levels as the following order: BNZF-4 > BNZF-3 > BNZF-2 > BNZF-1, ranging from highest values 0.802 cm2.g−1 to lowest value 0.406 cm2.g−1 at 0.0595 MeV, respectively. The improvement in the absorption coefficient (μ) values for the manufactured glass reduce the half-value thickness for the manufactured glass samples gets lowered as the μ values gets enhanced. Furthermore, the manufactured samples with high concentration of ZnO shows a superior ionized radiation shielding performance compared to other commercial borate-based glass. Hence, the manufactured sample coded BNZF-4 is a very wise choice for gamma shielding application in various sectors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yasmin, S. et al. Studies of ionizing radiation shielding effectiveness of silica-based commercial glasses used in Bangladeshi dwellings. Res. Phys. 9, 541–549 (2018).

Sayyed, M. I., Elmahroug, Y., Elbashir, B. O. & Issa, S. Gamma-ray shielding properties of zinc oxide soda lime silica glasses. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron 28, 4064–4074 (2017).

Imheidat, M. A. et al. Radiation shielding, mechanical, optical, and structural properties for tellurite glass samples. Optik 268, 169774 (2022).

Saeed, A. et al. Glass materials in nuclear technology for gamma-ray and neutron radiation shielding: A review. Nonlinear Opt., Quantum Opt. 53(202), 107–159 (2021).

Saeed, A. Elastic, transparent, and thermally stable borate glass reinforced by barium as an efficient gamma ray attenuator. Mater. Today Commun. 38, 108361 (2024).

Aloraini, D. A., Abu-raia, W. A. & Saeed, A. An efficient attenuator for gamma rays and slow neutrons of elastic and transparent lead sodium zinc calcium borate glass. Opt. Quant. Electron 56, 340 (2024).

Stepanov, V. A., Demenkov, P. V. & Nikulina, O. V. Radiation hardening, and optical properties of materials based on SiO2. Nucl. Energ. Technol. 7, 145–150 (2021).

El-Samrah, M. G., Abdel-Rahman, M. A. & El Shazly, R. M. Effect of heating on physical, mechanical, and nuclear radiation shielding properties of modified concrete mixes. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 153, 104–110 (2018).

Roman, J., Michał, A. G., Wojciech, K. & Mariusz, D. Application of a non-stationary method in determination of the thermal properties of radiation shielding concrete with heavy and hydrous aggregate. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 130, 882–892 (2019).

Reza, B., Alireza, K. M., Seyed, P. S., Bakhtiar, A. & Mojtaba, S. Determination of gamma ray shielding properties for silicate glasses containing Bi2O3, PbO, and BaO. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 479, 62–71 (2018).

Yin, S., Wang, H., Li, A., Ma, Z. & He, Y. Study on Radiation shielding properties of new barium-doped zinc tellurite glass. Materials 15, 2117 (2022).

Sayyed, M. I. et al. Development of a novel MoO3-doped borate glass network for gamma-ray shielding applications. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136, 108 (2021).

Yin, S. et al. Nuclear radiation shielding performance of the new lead-free TeO2-Bi2O3-ZnO-BaF2 glass. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 21(4), 2906–2914 (2024).

Sayyed, M. I., Olarinoye, O. I. & Elsafi, M. Assessment of gamma-radiation attenuation characteristics of Bi2O3–B2O3–SiO2–Na2O glasses using Geant4 simulation code. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136, 535 (2021).

Zeed, Mona Abo, El Shazly, Raed M., Elesh, Eman, El-Mallah, Hanaa M. & Saeed, Aly. Gamma rays and neutrons attenuation performance of a developed lead borate glass for radiotherapy room. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 200(4), 355–367 (2024).

Abu-raia, W. A. et al. Ni ions doped oxyflourophosphate glass as a triple ultraviolet–visible–near infrared broad bandpass optical filter. Sci. Rep. 12, 16024 (2022).

Kavaz, E. et al. Estimation of gamma radiation shielding qualification of newly developed glasses by using WinXCOM and MCNPX code. Prog. Nucl. Energ. 115, 12–20 (2019).

Kolavekar, S. B., Ayachit, N., Jagannath, G., NagaKrishnakanth, K. & Rao, S. V. Optical, structural and Near-IR NLO properties of gold nanoparticles doped sodium zinc borate glasses. Opt. Mater. 83, 34–42 (2018).

Paz, E. et al. Physical, thermal and structural properties of Calcium Borotellurite glass system. Mater. Chem. Phys. 178, 133–138 (2016).

Yin, S., Wang, H., Wang, S., Zhang, J. & Zhu, Y. Effect of B2O3 on the radiation shielding performance of telluride lead glass system. Crystals 12, 178 (2022).

Alotaibi, B. M. et al. Structural, optical, and gamma-ray shielding properties of a newly fabricated P2O5–B2O3–Bi2O3–Li2O–ZrO2 glass system. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136, 224 (2021).

Rammah, Y. S., Abouhaswa, A. S., Sayyed, M. I., Tekin, H. O. & El-Mallawany, R. Structural, UV and shielding properties of ZBPC glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 509, 99–105 (2019).

Luo, H. et al. Compositional dependence of properties of Gd2O3–SiO2–B2O3 glasses with high Gd2O3 concentration. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 389, 86–92 (2014).

Zeed, Mona Abo, El Aly Saeed, R. M., Shazly, H. .M. . El. - & Mallah, E. Elesh. Double effect of glass former B2O3 and intermediate Pb3O4 augmentation on the structural, thermal, and optical properties of borate network. Optik 272, 170368 (2023).

Elbatal, Aya, Farag, Mohammed A., El-Okr, Mohammed & Aly saeed.,. Influence of the addition of two transition metal ions to sodium zinc borophosphate glasses for optical applications. Egypt. J. Chem. 64(7053), 7058. https://doi.org/10.21608/EJCHEM.2021.79765.3921 (2021).

Sun, X.-Y. et al. Luminescence properties of scintillating glass doped with rare-earth and transition metal ions. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect A Accel. Spectrometers, Detect. Assoc. Equip. 716, 9095 (2013).

More, C. V. et al. Polymeric composite materials for radiation shielding: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 19(2057), 2090 (2021).

Akman, F. et al. Gamma attenuation characteristics of CdTe-Doped polyester composites. Prog. Nucl. Energ. 131, 103608 (2021).

Sayyed, M. I. et al. A Study on the gamma radiation protection effectiveness of nano/Micro-MgO-reinforced novel silicon rubber for medical applications. Polymers 14(14), 2867 (2022).

Sayyed, M. et al. Influence of increasing SnO2 content on the mechanical, optical, and gamma-ray shielding characteristics of a lithium zinc borate glass system. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 1–13 (2022).

More, C. V., Alavian, H. & Pawar, P. P. Evaluation of gamma ray and neutron attenuation capability of thermoplastic polymers. Appl. Radiat. Isot. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2021.109884 (2021).

More, C. V. et al. Extensive theoretical study of gamma-ray shielding parameters using epoxy resin-metal chloride mixtures. Nucl. Technol. Radiat. Prot. 35(2), 138–149 (2020).

More, C. V., Lokhande, R. M. & Pawar, P. P. Effective atomic number and electron density of amino acids within the energy range of 0.122–1.333 MeV. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 125, 14–20 (2016).

Akkaş, A. Determination of the tenth and half value layer thickness of concretes with different densities. Acta Phys. Pol. 129(4), 770–772 (2016).

Dahinde, P. S. et al. Analysis of half value layer (HVL), Tenth value layer (TVL) and mean free path (MFP) of some oxides in the energy range of 122KeV to 1330KeV. Ind. J. Sci. Res. 9(2), 79–84 (2019).

More, C. V. et al. UPR/Titanium dioxide nanocomposite: Preparation, characterization and application in photon/neutron shielding. App.l Radiat. Isot. 194, 110688 (2023).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing the first draft of the manuscript and reviewing editing were performed by M.I Sayyed, Chaitali V More, Ali. Hedaya, Mohamed. Elsafi. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elsafi, M., Sayyed, M.I., Hanafy, T.A. et al. Experimental study of gamma-ray attenuation capability of B2O3-ZnO-Na2O-Fe2O3 glass system. Sci Rep 14, 19141 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68941-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68941-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Gamma radiation shielding effectiveness of PbO2 doped borosilicate glasses

Scientific Reports (2025)