Abstract

In this study, PROP adsorption was investigated using activated carbon derived from Bactris Guineensis residues and physical statistical modeling. The characterization results indicate high specific surface areas (624.72 and 1125.43 m2 g−1) and pore diameters (2.703 and 2.321 nm) for the peel and stone-activated carbon, respectively. Adsorption equilibrium was investigated at different temperatures (298 to 328 K), and it was found that the adsorption capacity increased with temperature, reaching maximum values of 168.7 and 112.94 mg g−1 for the peel and stone-activated carbon, respectively. The application of physical statistical modeling indicates that a monolayer model with one energy site is adequate for describing both systems, with an R2 above 0.986 and a low BIC of 20.021. According to the steric parameters, the density of molecules per site tends to increase by 116.9% for the stone and 61.6% for the peel. In addition, the model indicates that the number of molecules decreases with increasing temperature from 1.36 to 0.81 and from 1.03 to 0.82. These results indicate that temperature controls the number of receptor sites and the orientation in which propranolol is adsorbed at the surface. The adsorption energies were similar for both systems (approximately 10 kJ mol−1), which indicates that the adsorption occurred due to physical interactions. Finally, the application of thermodynamic potential functions indicates that the maximum entropy is reached at concentrations of half-saturation (Ce 3.85 and 4.6 mg L−1), which corresponds to 1.60 × 10–18 and 1.86 × 10–18 kJ mol−1 K−1 for the stone and peel, respectively. After this point, the number of available sites tends to decrease, which indicates the stabilization of the system. The Gibbs energy tended to decrease with increasing concentration at equilibrium, reaching minimum values of − 1.73 × 10–19 and − 1.99 × 10–19 kJ mol−1, respectively. Overall, the results obtained here further elucidate how the adsorption of propranolol occurs for different activated carbons from the same source.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emerging micropollutants present in hospital, industrial, domestic, agricultural, and livestock effluents1 are residues that have been released in different ways into the environment, resulting in the contamination of surfaces, soils, and water bodies. Conducting long-term studies is necessary to comprehensively comprehend the ecological repercussions and consumption patterns of living organisms in relation to these pollutants2. The growing awareness of ocean water pollution, in line with the sustainable development objectives established by the United Nations (UN), has driven the implementation of environmental policies and legislation at the global level3. However, there are emerging pollutants, such as drugs, which still lack regulation and are constantly discarded in the environment4. Even at low concentrations (on the order of ng to µg per liter), these substances can present a high degree of toxicity to aquatic organisms over time5.

The growing consumption of drugs for hypertension in recent years has led to an increase in the presence of propranolol hydrochloride (C16H21NO2. HCl) in the environment6. A substantial portion of this compound undergoes limited absorption within the human body and is subsequently excreted in urine, leading to its presence in effluent streams. It is important to note that this drug compound, once present in water resources, exhibits significant chemical persistence. This means that it remains in the environment for an extended period without breaking down. Furthermore, its primary metabolite, 4-hydroxy propranolol, is not only persistent but also toxic. This combination of persistence and toxicity raises concerns about its potential impact on aquatic ecosystems and human health2. Conventional effluent treatment processes have shown only partial removal of this contaminant, resulting in its release into water bodies, which poses a risk to aquatic biota, including the green algae S. vacuolatus4. Issues involving its high consumption and chemical characteristics contributed to the detection of propranolol (PROP) in Brazil's most varied surface water compartments and even in sewage and treatment plants3. To address this problem, several techniques have been studied, especially for the removal and degradation of this compound7. Adsorption using new adsorbents obtained from plant residues, such as activated carbon, has emerged as a promising option8. These carbonaceous materials, which are predominantly composed of carbon, possess elevated surface areas and well-developed pores, which are critical attributes for effective adsorbents9.

The arboreal species Bactris guineensis is a widely distributed palm in the hillside region of the Colombian Caribbean. Its rapid adaptation to the local climate allowed the species to occupy all of Central America, starting to present great commercial value due to its characteristic fruits. Popularly, the fruits are called corozo; they are small in size with a rounded shape, and the edible part is the pulp, causing the peel and the core to be discarded. The purple-colored pulp is rich in nutrients and has a vast list of applications in Colombian cuisine, being used in the production of wines, juices, jellies, sweets, and even paints10. The cultivation of this palm tree presents a challenge in managing substantial volumes of residual biomass, given that a significant portion of the fruit consists of seeds. On average, a single plant yields approximately 30 kg of fruit per year, resulting in approximately 750 kg of fruit per hectare under cultivation. Studies have shown that corozo pulp has antioxidant activity due to its dark color11,12,13. However, to date, no studies have explored the potential of corozo residual biomass as an adsorbent material, especially for the removal of emerging contaminants such as propranolol.

Adsorption is often described through traditional models, such as the Freundlich or Langmuir models. As good as these models are at describing experimental data, they fail to provide relevant information about the system14. On the other hand, physical statistical models (PSMs) are different approaches based on particle states between dissolved and adsorbed15,16,17. To date, investigations of propranolol through physical statistical modeling are scarce in the literature, especially the work of Sellaoui et al.18, which employs the aforementioned modeling for propranolol/magnetic activated carbon. Therefore, in the present study, two adsorbents were developed from the peel and stone of Bactris guineensis fruit. Both residues underwent carbonization with zinc chloride (ZnCl2), and the original and carbonized materials were subjected to various characterization techniques for analysis. Later, physical statistical modeling was employed for both systems at different temperatures (from 298 to 328 K).

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

All the chemicals, reagents, and solvents utilized in the present study were of analytical grade and were acquired from Sigma‒Aldrich, USA. Fruits were purchased from a market for consumption to produce juice. The residues were separated and used for adsorption. To enhance textural characteristics such as surface area and pore development, zinc chloride (ZnCl2) was chosen as the activating agent. Propranolol hydrochloride (MW: 259.34 g mol−1) was selected as the adsorbate for pharmacological purposes. Isothermal studies were conducted using varying concentrations of propranolol (PROP). A standard solution was first prepared by diluting 1000 ppm of propranolol in methanol, as the drug exhibits low solubility. Subsequently, a solution of 1000 mg L−1 was obtained by further dilution of the stock solution. The additional concentrations utilized in the studies were produced by diluting the original concentration and thereafter stored in containers made of amber material.

Synthesis and characterization of material

The paragraph delineates the methodology employed in the production of activated carbon derived from residual fruits of Bactris guineensis. The fruits were collected from local market, first subjected to a washing procedure, after which the skins and core were carefully separated. Next, both the peels and core were subjected to drying, grinding, and sieving procedures to obtain a uniform particle size. To remove the extractives, the materials were washed with ethanol. The liquid and solid phases were separated using the decantation technique, and this procedure was repeated iteratively until the liquid phase achieved clarity. The solid materials were dried and characterized. The residual material was then employed to produce activated carbon, with zinc chloride serving as the activating agent. The precursor material and salt were mixed and heated in an oven. The dry materials were macerated and then subjected to pyrolysis under a N2 atmosphere. After pyrolysis, the salt was removed using HCl. The pyrolyzed material was washed with water, dried, crushed, and sieved to obtain activated carbon. A further detailed description of the method is given in the Supplementary Material (S.1). The activated carbons were named according to their origin: activated carbon from the core (ACC) and activated carbon from the peel (ACP).

Adsorption experiments

The samples underwent agitation using a thermostatic shaker that operated at a consistent pace. The detection of propranolol (PROP) within the aqueous medium was ascertained using a spectrophotometer calibrated to a wavelength of 255 nm. To ensure reliability, all experiments were replicated three times, and after each trial, the samples were centrifuged to separate the PROP from the activated carbon. Isothermal experiments were carried out at a dosage of 0.7 g L−1 and a pH of 10. Isothermal curves were generated at various concentrations of bark/PROP and stone/PROP, along with different temperatures. To reach equilibrium in the PROP/AC system, the samples were stirred for 5 h in Erlenmeyer flasks. Further details are given in the Supplementary Material.

Physics-statistics models

The PSMs are based on the possible exchanges that occur between the particles in the free state (dissolved in the medium) and the particles that are adsorbed16. The PSMs are based on the grand canonical ensemble, which considers the change in particle number in both phases. In addition, several hypotheses are considered: (i) interactions between the propranolol molecules are negligible15; (ii) the dissolution process diminishes the number of free states, resulting in exchanges through translation19; and (iii) vibrational and rotational degrees are neglected in comparison with translation17. In general, PSMs consider the number of molecules (n) adsorbed onto receptor sites (Nm).

The monolayer model with one energy site (MLO) is based on Eq. (1). where n molecules are adsorbed, forming an energetically homogenous layer, which is represented by the grand canonical partition function, according to Eq. (2)20:

This leads to the following solution, which can be found elsewhere21:

where qe is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium (mg g−1), qm is the maximum adsorption capacity (mg g−1), Ce is the equilibrium at concentration (mg L−1), and C1/2 is the concentration at half-saturation (mg L−1).

Other models, such as the dual layer with one energy site (DLO) and the triple layer with one energy site (TLO), consider that the adsorbate can further form new layers according to reaction Eqs. (4) and (5):

This leads to the following grand canonical partition functions:

The solution of the grand canonical partition functions (Eqs. 6 and 7) leads to the DLO and TLO, which are expansions of the MLO22,23,24,25:

The selected model considers that the site's energies are the same, i.e., the energy is homogeneous for all the adsorption. The adsorption energy (ΔEa kJ mol−1) can be obtained according to Eq. (4)26:

where Cs is the concentration solubility (200 mg L−1, taking into consideration the dilution effect on methanol), R is the gas constant (8.31 × 10–3 kJ mol−1 K−1), and T is the temperature of the system (K).

Further exploration of MLO through potential thermodynamic functions

Thermodynamic potential functions are a group of equations that describe thermodynamic properties. Given that the MLO model relies on the grand canonical ensemble, it becomes feasible to employ the original functions for computing the partial derivatives of β and µ. These derivatives are crucial for determining the thermodynamic properties of the system according to the following equations26:

Sa is the evolution of the configuration entropy (kJ mol−1 K−1), Ga is the evolution of Gibb’s adsorption-free energy (kJ mol−1), EI is the evolution of the internal energy (kJ mol−1), Zgc is the total grand canonical partition, μ is the chemical potential of propranolol in relation to rotation (J mol−1), β is the inverse of the Boltzmann constant (kB = 1.380649 × 10–23 J K−1) and system temperature (T, K), the Planck constant (6.62607004 × 10–34 m2 kg s−1) and m is the propranolol mass (259,340 mg mol−1).

From the application of the partial derivatives and the MLO, it is possible to obtain the thermodynamic properties as a function of the propranolol concentration at equilibrium (Ce mg L−1) according to the following Equations:

Parameter estimation and model validation

The steric parameters were assessed through MATLAB scripting programming, leveraging built-in functions. More precisely, the initial guess estimation was accomplished using the particle swarm function, while lsqnonlin or nlinfit were utilized to correct inaccurate particlewarm estimations. The distinction between nlinfit and lsqnonlin lies in their treatment of restrictions. The former is designed for cases with limited boundaries, whereas the latter enables optimization without predefined boundaries. The fitting was validated through the evaluation of the steric parameters and the application of statistical indicators, as described in the Supplementary Material.

Regeneration study

An evaluation of the developed AC regeneration tests was conducted. First, the already used adsorbent was separated from the solution. Second, the loaded adsorbent was added to an HCl solution (25 mL 75% v/v), and the flask was stirred for 2 h. Finally, the separated adsorbent was subjected to adsorption under the same conditions as those used for the isotherms. The completion of these steps is known as a cycle, which was performed up to 6 times in this work.

Results and discussion

Characterization results

In the pyrolysis phase, a significant portion of cellulose and lignin undergo conversion into volatile material, impacting the ultimate yield and augmenting the surface area. Consequently, approximately 29% of the carbonaceous skeleton formed from both residues was produced as a result of this process. This finding aligns with other studies that similarly employed ZnCl2 in a 1:1 ratio27,28,29. As shown in Table 1, the pore volume of the charred skin was 4.223 × 10–1 cm3 g−1, the pore diameter was 2.70 nm, and the surface area was 624.728 m2 g−1. Carbonization using zinc chloride also resulted in favorable textural characteristics for an adsorbent from the core (Table 1), with an even greater surface area compared to that of the skin (SBET = 1125.43 m2 g−1). Furthermore, the material showed good pore development (Vp = 3.241 × 10–1 cm3 g−1; Dp = 2.321 nm). The surface area is one of the main factors influencing the adsorption capacity of a material. However, carbonization with ZnCl2 may limit the good performance compared to that of PROP for both adsorbents due to certain factors. Compared with the results obtained with other carbons developed in the literature, we observed that the surface area obtained from carbonization with zinc chloride is significantly greater. For example, in a study carried out by Liu et al.30 using coconut shells as precursors, the surface area was reported to be 803 m2 g−1 after chemical activation with ZnCl2. Another study carried out by Ferrari et al.31 using grape seed waste reported a surface area of 542 m2 g−1 after carbonization with ZnCl2.

Figure S1 enables the identification of the primary functional groups present on the surface of the materials. Initially, the functional groups within the carbonized material derived from the corozo core were analyzed. (Fig. S1A), and all functional groups identified in the second material (Fig. S1B) will not be reported. Therefore, the residues before and after carbonization share similar chemical groups. The 3441 cm−1 O–H bond region occurred in the same way as it remained after heating but with lower intensity32. The binding of CH (2918 cm−1), which was exclusively detected in the precursor material, suggested that the pyrolysis step led to the consumption of this group33. The disappearance of these functional groups corroborates the loss of volatile material that occurs during the pyrolysis process34. The presence of CO groups (1743 cm−1) in both materials is generally attributed to the presence of ketones35. The carboxylate stretching vibrations are associated with the spectral band at approximately 1636 cm−136. Aromatic rings are also found at 1452 cm−1 in the precursor material34. The band present in the 1041 cm−1 region corresponds to the secondary alcohol stretching of CO bonds37. Regarding the carbonization of the core (Fig. S1B), only the bands at 2851 cm−1 were not observed in Fig. S1A. Asymmetric vibrations of CH2 in the precursor were found at 2851 cm−138. Therefore, both materials share similar functional groups corresponding to structures that are formed by cellulose, and when lignin is added, the pyrolysis step reduces the heterogeneity of the surface, resulting in the formation of carbonaceous material with carbon as the final product.

X-ray diffraction serves as a structural analysis methodology facilitating the elucidation of the crystalline structure of a material based on the acquired diffraction pattern. Figure S2 shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of the original sample and the charred sample for both residues. In the case of the sample in question, both patterns (Fig. S2A and B) show the presence of amorphous carbon in the form of a long diffraction band between 15° and 30°. Amorphous carbon is a disorganized and irregular form of carbon that does not have a definite crystal structure39. However, carbonization can lead to the formation of more organized and crystalline structures, which may explain the decrease in diffraction bandwidth and increase in intensity (Fig. S2B). The empty spaces present in the amorphous structure can be occupied by adsorbate molecules, which are substances adsorbed on the surface of the material40. This can be useful for the adsorption of substances in purification or separation processes, as in the case of this study41.

The micrographs before the carbonization step (Fig. S3A and C) show that the surface of the residual corozo biomass is composed of irregular particles of different sizes. After carbonization with ZnCl2, the particles maintained their irregular shape and varied in size (Fig. S3B and D). However, the surface shape was modified, becoming smoother and more regular with some randomly distributed cavities. Similar morphological modifications have been reported in the literature in several studies of carbonized materials of plant origin for the purpose of removing different compounds42,43,44,45.

Propranolol adsorption equilibrium and application of the PSM

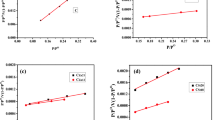

The experimental results and the model predictions are shown in Fig. 1. In both cases, the adsorption capacity tends to increase according to the propranolol equilibrium concentration and the temperature. These results indicate that ACC and ACP have strong affinities for propranolol. For the temperature, this indicates that both systems are endothermic, indicating that the temperature causes some modification of the material or that the propranolol molecules present higher energy or change the solubility. The shape of the isotherm may be related to the L2 shape according to the Giles classification, without the presence of a plateau. This indicates that the adsorption capacity will steadily decrease with increasing concentration at equilibrium due to the decrease in the number of vacant sites46. The choice of the best PSM was based on statistical indicators (Table S.1) and the stereographic parameters of the mode. In this case, it was found that all the employed models presented good statistical indicators (no major significance was found) regarding the correlation factor (R2 > 0.98), average relative error (ARE < 7.84%), and minimum squared error (MSE). Thus, the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was used as an indicator for selecting the model; the lower the BIC value is, the more suitable the model. Therefore, from the comparison of the BIC values, the MLO model was selected, and the DLO and TLO models were discarded. MLO indicates that the propranolol molecules are adsorbed, forming a monolayer on the surface of the ACC and/or ACP, and it is also assumed that the adsorption energy is the same for all the adsorbed molecules21,47.

Figure 2A illustrates the correlation between the anticipated adsorption capacity and the system temperature. Upon scrutinizing the parameters, it was observed that the adsorption capacity exhibited an upward trend in both systems, directly mirroring the inherent characteristics of the adsorption system. For ACC/propranolol, the adsorption capacity increased from 105.82 to 168.70 mg g−1 as the experimental value increased from 100.24 to 112.94 mg g−1, which corresponds to an ARE of 14.28%. For ACP/propranolol, the predicted adsorption capacity increased from 124.49 to 160.0 mg g−1, with experimental values corresponding to 117.2 to 145.45 mg g−1, corresponding to an ARE of 7.89%. Overall, this indicates that the adsorption capacity predicted by the MLO is in agreement with the experimental data. The evolution of the receptor site (Nm) density according to temperature is shown in Fig. 2B. Similar behaviors emerge for the Nm parameters, which indicates that propranolol tends to have similar behavior for both systems. For the ACC/propranolol system, the receptor density started at 77.76 and reached 168. 70 mg g−1 at the highest temperature of 328.15 K. In the ACP/propranolol system, Nm also increased linearly with temperature, starting at 120.0 to 194.56 mg g−1 according to the temperature. The increase in Nm with temperature can be attributed to two different effects: (i) a decrease in the number of molecules adsorbed per site or (ii) the appearance of new receptor sites due to the temperature effect. Therefore, it is possible that ACP presented a greater density of molecules per site than ACC22,48.

Stereographic parameters evolution according to the temperature for the ACC/propranolol and ACP/propranolol systems; (A) anticipated adsorption capacity in correlation with the system temperature, (B) densities of the receptor sites (Nm) according to the temperature, (C) number of molecules versus temperature, (D) adsorption energy versus temperature, (E) main adsorption mechanism of propranolol for ACC and ACP.

The number of molecules per site (n), also called the stoichiometric coefficient, can be considered the most important parameter that explains the adsorption of propranolol from different points of view. From a chemical point of view, this parameter describes the degree of aggregation of propranolol for both22. In this study, a similar trend was found for both adsorbents, where the number of molecules tended to decrease with temperature (Fig. 2C). For the ACC, the values decreased from 1.36 to 0.8176, and for the ACP, the values ranged from 1.03 to 0.82. The magnitude and change of these values indicate different behaviors. The first is the magnitude, which indicates the orientation of the adsorbed propranolol molecules, which can be separated into two possibilities: when n > 1, the propranolol is adsorbed horizontally, and when n < 1, the propranolol molecules are adsorbed in parallel. For the ACC, the initial value is 1.36 at 298.15 K, followed by 1.06 at 308.15 K, meaning that at the early initial temperature, the propranolol molecules will be adsorbed in a horizontal manner. As the temperature of the system increases, the manner in which the propranolol molecules are adsorbed in this system shifts in a parallel way, since the values for n reach 0.933 and 0.817 for 318.15 and 328.15 K, respectively. Similarly, for the propranolol/ACP system, the initial values for n were found to be 1.03 and 1.06 for 298.15 and 308.15 K, respectively. However, as the temperature starts to increase from 308.15 K, it is possible to quickly shift the position of the adsorption since the values are under one unit. The second observation is the overall change in the n values, which decreases almost linearly according to the system temperature evolution, revealing the reverse behavior of the receptor density. This further corroborates the theory that temperature causes the generation of new receptors that were previously hidden due to thermal expansion.

The application of MLO also provides information regarding the concentration of half-saturation, which is employed for the determination of the adsorption energy, as shown in Fig. 2D. The adsorption energy is a useful parameter since it indicates the nature of the adsorption and provides information regarding the type of adsorption mechanism involved. In this case, it was found that the adsorption energy tends to increase linearly with the evolution of the system temperature, indicating that the adsorption of propranolol for both systems is endothermic. For the magnitude of the adsorption energy, the maximum value is approximately 10.8 kJ mol−1 for both systems, and it is possible to presume that the adsorption is based on physical interactions8.

Possible adsorption mechanism

From the characterization results, propranolol speciation and modeling results were used to propose an adsorption mechanism. For both materials, classical groups such as O–H, C–H, CO, and CH2 indicate the possible formation of aromatic rings49,50,51. Propranolol has two states according to the pH of the solution (Fig. S4), meaning that at pH 10, 99% of the molecules are in neutral form. For the adsorbent surface, the pH values at zero charge are 6.56 and 6.44 for the stone and peel, respectively (Fig. S5). This means that the surface will be negatively charged at pH 10. Finally, the adsorption energy was found to be lower than 40 kJ mol−1, which strongly indicates that the coupling of the propranolol molecules onto the surface of the adsorbents is due to physical interactions. Thus, it is expected that the propranolol molecules are adsorbed through hydrogen bonding (due to the presence of hydrogen in the adsorbate and adsorbents)52, electrostatic interactions (due to the even being a neutral molecule part of its negative region, Fig. S6)23, and anion-π interactions (due to the surface charge and aromatic rings of the propranolol)8 as shown in Fig. 2E.

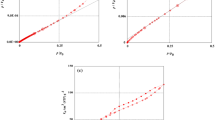

Thermodynamic property simulation results

The evolution of the configuration entropy is shown in Fig. 3. Both systems presented similar trends in terms of concentration equilibrium and system temperature. In both cases, it was found that the entropy tends to increase with the equilibrium concentration, reaching maximum values around the concentration at half-saturation, also called entropic peaks. After this point, the entropy starts to diminish until reaching equilibrium (Ce > 100 mg L−1), which is not shown. The lack of equilibrium in the evolution of thermodynamic parameters is directly related to the experimental data not reaching the isotherm plateau, indicating that further adsorption can still occur. Regarding the temperature, both systems tended to follow the same trend, where the entropy increased with temperature due to the endothermic nature of the systems. However, it should be noted that all the stereographic parameters can influence the thermodynamic properties; in this case, minor overlap occurs for the ACP/propranolol systems, as shown in Fig. 3B. This can be related to the number of molecules per site; in this case, the values are similar, and at 308.15 K, the number of molecules per site increases by 0.03.

The evolution of Gibb’s free energy is shown in Fig. 4A and B. Regarding the concentration at equilibrium effect, it was found that the Gibbs energy tends to quickly increase at lower concentrations, and this effect is directly related to the number of available sites at the initial stage of adsorption. In addition, it was found that the Gibbs energy tends to behave similarly for both systems, where the energy tends to be more negative according to the system temperature, directly reflecting the endothermic nature of the systems, which is mainly related to the appearance of hidden sites. Additionally, the configuration entropy of the Gibbs energy did not reach equilibrium, which is related to the possibility of further adsorption of propranolol.

Finally, Fig. S7A and B present the progression of the internal energy with respect to the system, equilibrium concentration, and system temperature. Similar to the other results obtained for thermodynamic proprieties, the equilibrium concentration tends to increase the internal energy without reaching equilibrium, which also indicates that the adsorption capacity could be improved. For the temperature effect, the internal energy presents the same behavior as the Gibbs adsorption-free energy. The magnitude tends to increase with temperature and is negative throughout all the simulated ranges. The negative signal here also indicates that the adsorption is endothermic, with the adsorption naturally increasing at higher concentrations.

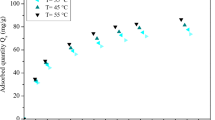

Regeneration performance

The regeneration results for the ACC and ACP are shown in Fig. 5. The first aspect to be noted is that both adsorbents present a linear behavior; this type of behavior is related to the affinity of the material for propranolol and the low loss of activated sites per cycle. A minor percentage of removal was 71.1% for ACC and 66.2% for ACP, which was expected since ACC presented a greater adsorption capacity than ACP. Finally, it is possible to estimate that ACC has an average loss of 5.77% per cycle, while ACP has a slightly greater loss of 6.76% per cycle.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from [Dison S. P. Franco] Still, restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Dison S. P. Franco.

References

Bonilla-Petriciolet, A., Mendoza-Castillo, D. I. & Reynel-Ávila, H. E. Adsorption processes for water treatment and purification. Adsorpt. Process. Water Treat. Purif. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58136-1 (2017).

Bound, J. P. & Voulvoulis, N. Predicted and measured concentrations for selected pharmaceuticals in UK rivers: Implications for risk assessment. Water Res. 40, 2885–2892 (2006).

Riasa, I. N. P. & Kawilarang, B. “The effect of propanolol and metformin on clinical outcomes in burns patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis” burn. Open https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burnso.2023.04.002 (2023).

Canadas, K. T., Baum, E. D., Lee, S. & Ostrower, S. T. Case report: Treatment failure using propanolol for treatment of focal subglottic hemangioma. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 74, 956–958 (2010).

Thue, P. S. et al. Single-step pyrolysis for producing magnetic activated carbon from tucumã (Astrocaryum aculeatum) seed and nickel(II) chloride and zinc(II) chloride. Application for removal of nicotinamide and propanolol. J. Hazard. Mater. 398, 122903 (2020).

Cho, C. W. et al. Development of prediction models for adsorption properties of chitin and chitosan for micropollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 426, 131341 (2021).

Hassan, N., Maldonado-Valderrama, J., Gunning, A. P., Morris, V. J. & Ruso, J. M. Investigating the effect of an arterial hypertension drug on the structural properties of plasma protein. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 87, 489–497 (2011).

Georgin, J., Franco, D. S. P., Da Boit Martinello, K., Lima, E. C. & Silva, L. F. O. A review of the toxicology presence and removal of ketoprofen through adsorption technology. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107798 (2022).

Georgin, J. et al. Effective adsorption of harmful herbicide diuron onto novel activated carbon from Hovenia dulcis. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 654, 129900 (2022).

Sequeda-Castañeda, L. G., Barrera-Bugallo, A. R., Celis, C., Iglesias, J. & Morales, L. Evaluation of antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of extracts from fruits in fibroblastoma HT1080 cell lines: Four fruits with commercial potential in Colombia. Emirates J. Food Agric. 28, 143–151 (2016).

Brieva-Oviedo, E., Maia, A. C. D. & Núñez-Avellaneda, L. A. Pollination of Bactris guineensis (Arecaceae), a potential economically exploitable fruit palm from the Colombian Caribbean. Flora Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 269, 151628 (2020).

Diaz-Uribe, C. et al. TiO2 thin films sensitization with natural dyes extracted from Bactris guineensis for photocatalytic applications: Experimental and DFT study. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 24, 407–416 (2020).

Osorio, C., Carriazo, J. G. & Almanza, O. Antioxidant activity of corozo (Bactris guineensis) fruit by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 233, 103–108 (2011).

Amrhar, O., El Gana, L. & Mobarak, M. Calculation of adsorption isotherms by statistical physics models: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 19, 4519–4547 (2021).

Bouzid, M., Bouaziz, N., Torkia, Y. B. & Lamine, A. B. Statistical physics modeling of ethanol adsorption onto the phenol resin based adsorbents: Stereographic, energetic and thermodynamic investigations. J. Mol. Liq. 283, 674–687 (2019).

Ben Khemis, I., Bouzid, M., Mechi, N. & Ben Lamine, A. Statistical physics modeling and interpretation of the adsorption of enantiomeric terpenes onto the human olfactory receptor OR1A1. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 171, 428–434 (2021).

Bouzid, M., Sellaoui, L., Khalfaoui, M., Belmabrouk, H. & Lamine, A. B. Adsorption of ethanol onto activated carbon: Modeling and consequent interpretations based on statistical physics treatment. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 444, 853–869 (2016).

Sellaoui, L. et al. Application of a multilayer physical model for the critical analysis of the adsorption of nicotinamide and propranolol on magnetic-activated carbon. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 30184–30192 (2022).

Ben Khemis, I. et al. Interpretations of key food odorant dose-olfactory response curves using statistical physics method. J. Mol. Liq. 322, 114553 (2021).

Missaoui, N. et al. Interpreting of the carbon dioxide adsorption on high surface area zeolitic imidazolate Framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanoparticles using a statistical physics model. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 360, 112711 (2023).

Knani, S., Mathlouthi, M. & Lamine, A. B. Modeling of the psychophysical response curves using the grand canonical ensemble in statistical physics. Food Biophys. 2, 183–192 (2007).

Georgin, J. et al. Efficient removal of naproxen from aqueous solution by highly porous activated carbon produced from Grapetree (Plinia cauliflora) fruit peels. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 106820 (2021).

Vieira, Y. et al. Mechanistic insights and steric interpretations through statistical physics modelling and density functional theory calculations for the adsorption of the pesticides atrazine and diuron by Hovenia dulcis biochar. J. Mol. Liq. 367, 120418 (2022).

Moussout, H., Dehmani, Y., Franco, D. S. P. & Georgin, J. Towards an in-depth experimental and theoretical understanding of the cadmium uptake mechanism on a synthesized chitin biopolymer. J. Mol. Liq. 383, 122106 (2023).

Dehmani, Y. et al. Comparison of phenol adsorption property and mechanism onto different Moroccan clays. Water 15, 1881 (2023).

Knani, S., Khalfaoui, M., Hachicha, M. A., Mathlouthi, M. & Ben Lamine, A. Interpretation of psychophysics response curves using statistical physics. Food Chem. 151, 487–499 (2014).

Suo, F., You, X., Ma, Y. & Li, Y. Rapid removal of triazine pesticides by P doped biochar and the adsorption mechanism. Chemosphere 235, 918–925 (2019).

Üner, O. & Bayrak, Y. The effect of carbonization temperature, carbonization time and impregnation ratio on the properties of activated carbon produced from Arundo donax. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 268, 225–234 (2018).

Cunha, M. R. et al. Removal of captopril pharmaceutical from synthetic pharmaceutical-industry wastewaters: Use of activated carbon derived from Butia catarinensis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 104506 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. Effect of modified coconut shell biochar on availability of heavy metals and biochemical characteristics of soil in multiple heavy metals contaminated soil. Sci. Total Environ. 645, 702–709 (2018).

Ferrari, V. et al. Chemical evaluation of by-products of the grape industry as potential agricultural fertilizers. J. Clean. Prod. 208, 297–306 (2019).

Wu, H., Gong, L., Zhang, X., He, F. & Li, Z. Bifunctional porous polyethyleneimine-grafted lignin microspheres for efficient adsorption of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid over a wide pH range and controlled release. Chem. Eng. J. 411, 128539 (2021).

Cruz González, G., Julcour, C., Chaumat, H., Jáuregui-Haza, U. & Delmas, H. Degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid by photolysis and photo-Fenton oxidation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 6, 874–882 (2018).

Lua, A. C., Yang, T. & Guo, J. Effects of pyrolysis conditions on the properties of activated carbons prepared from pistachio-nut shells. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 72, 279–287 (2004).

Bouchelta, C., Medjram, M. S., Bertrand, O. & Bellat, J. P. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from date stones by physical activation with steam. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 82, 70–77 (2008).

Li, X., Deng, S. & Fu, H. Inhibition of the corrosion of steel in HCl, H2SO4 solutions by bamboo leaf extract. Corros. Sci. 62, 163–175 (2012).

Mohd Din, A. T., Hameed, B. H. & Ahmad, A. L. Batch adsorption of phenol onto physiochemical-activated coconut shell. J. Hazard. Mater. 161, 1522–1529 (2009).

Spessato, L. et al. KOH-super activated carbon from biomass waste: Insights into the paracetamol adsorption mechanism and thermal regeneration cycles. J. Hazard. Mater. 371, 499–505 (2019).

Choudhary, M., Kumar, R. & Neogi, S. Activated biochar derived from Opuntia ficus-indica for the efficient adsorption of malachite green dye, Cu+2 and Ni+2 from water. J. Hazard. Mater. 392, 122441 (2020).

Ali, I., Al-Othman, Z. A. & Alwarthan, A. Synthesis of composite iron nano adsorbent and removal of ibuprofen drug residue from water. J. Mol. Liq. 219, 858–864 (2016).

Franco, D. S. P. et al. The production of activated biochar using Calophyllum inophyllum waste biomass and use as an adsorbent for removal of diuron from the water in batch and fixed bed column. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-26048-8 (2023).

Lin, S. H. & Juang, R. S. Adsorption of phenol and its derivatives from water using synthetic resins and low-cost natural adsorbents: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 90, 1336–1349 (2009).

Dural, M. U., Cavas, L., Papageorgiou, S. K. & Katsaros, F. K. Methylene blue adsorption on activated carbon prepared from Posidonia oceanica (L.) dead leaves: Kinetics and equilibrium studies. Chem. Eng. J. 168, 77–85 (2011).

Galhetas, M. et al. Carbon-based materials prepared from pine gasification residues for acetaminophen adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 240, 344–351 (2014).

Rodrigues, D. L. C. et al. Adsorption of amoxicillin onto high surface area–activated carbons based on olive biomass: Kinetic and equilibrium studies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 41394–41404 (2020).

Giles, C. H., Smith, D., D’Silva, A. P., Easton, I. A. & Smith, D. A general treatment and classification of the solute adsorption isotherm part. II. Experimental interpretation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 47, 766–778 (1974).

Ben Yahia, M. et al. Models for type VI adsorption isotherms from a statistical mechanical formulation. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 31, 341–357 (2013).

Franco, D. S. P., Georgin, J., Netto, M. S., da Boit Martinello, K. & Silva, L. F. O. Preparation of activated carbons from fruit residues for the removal of naproxen (NPX): Analytical interpretation via statistical physical model. J. Mol. Liq. 356, 119021 (2022).

Dehmani, Y. et al. Towards experimental and theoretical understanding of the adsorption behavior of phenol on a new activated carbon prepared from oak wood. J. Water Process Eng. 54, 103936 (2023).

Ramirez, R. et al. Transformation of residual Açai fruit (Euterpe oleracea) seeds into porous adsorbent for efficient removal of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid herbicide from waters. Molecules 27, 7781 (2022).

Bouzidi, M. et al. A comprehensive study on paracetamol and ibuprofen adsorption onto biomass-derived activated carbon through experimental and theoretical assessments. J. Mol. Liq. 376, 121457 (2023).

Gao, P., Fan, X., Wang, W. & Yang, C. Sustainable technologies for adsorptive removal of estrogens from water: A comprehensive review for current advances. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 110780 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through the Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/182/45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software: D. S. P. F, J. G, D. A, L. M, E.A.L. M. Data curation: D. S. P. F, J. G, D. A, L. M, E.A.L. M, A.H. K, MA. H, A. H. Formal analysis: D. S. P. F, J. G, D. A, L. M, E.A.L. M, A.H. K, MA. H, A. H. Visualization and investigation: D. S. P. F, J. G, D. A, L. M, E.A.L. M, A.H. K, MA. H, A. H. Writing—original draft: D. S. P. F, J. G, D. A. Supervision, writing—review and editing: D. S. P. F, J. G, D. A, L. M, E.A.L. M, A.H. K, MA. H, A. H.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Franco, D.S.P., Georgin, J., Allasia, D. et al. Investigation of propranolol hydrochloride adsorption onto pyrolyzed residues from Bactris guineensis through physics statistics modeling. Sci Rep 14, 18101 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68977-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68977-5