Abstract

During captivity, round stingrays, Urobatis halleri, became infected with the marine leech Branchellion lobata. When adult leeches were deprived of blood meal, they experienced a rapid decrease in body mass and did not survive beyond 25 days. If kept in aquaria with host rays, B. lobata fed frequently and soon produced cocoons, which were discovered adhered to sand grains. A single leech emerged from each cocoon (at ~ 21 days), and was either preserved for histology or molecular analysis, or monitored for development by introduction to new hosts in aquaria. Over a 74-day observation period, leeches grew from ~ 2 to 8 mm without becoming mature. Newly hatched leeches differed from adults in lacking branchiae and apparent pulsatile vesicles. The microbiome of the hatchlings was dominated by a specific, but undescribed, member of the gammaproteobacteria, also recovered previously from the adult leech microbiome. Raising B. lobata in captivity provided an opportunity to examine their reproductive strategy and early developmental process, adding to our limited knowledge of this common group of parasites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leeches are highly unusual annelids (Clitellata: Hirudinea) present in both terrestrial and aquatic habitats, that display a diversity of nutritional strategies, ranging from parasitic blood-feeding to predation. Piscicolid leeches comprise approximately 60 genera and 120 species which feed predominantly on the blood of fishes, including both teleosts and elasmobranchs1,2,3,4. Compared to terrestrial leeches, little is known about the biology of marine leeches, likely due to their seasonality, non-viability in captivity, and inaccessibility to their primary hosts5 although some information is available on leeches associated with aquaculture6.

External fertilization in the Clitellata mainly takes place in a thick-walled cocoon composed of outer wall material and albuminous fluid secreted by two separate cocoon glands1,5. Leeches deposit cocoons containing 1–10 small eggs, depending on the species2,7. Duration of cocoon development among the Piscicolidae is widely variable from 7 days to 8 months, and hatching appears to be dependent upon a specific temperature window8,9. For example, cocoons of the marine leeches Oceanobdella blennii Knight-Jones, 1940 and Piscicola salmositica Meyer, 1946 will only hatch at 6–7 °C and 5–12 °C, respectively7,8,10.

The piscicolid genus Branchellion Savigny, 1822 consists of eight species that parasitize elasmobranchs, primarily rays and skates, and occasionally teleosts2,11,12. Branchellion lobata Moore, 1952, a species of marine leech found off of California, Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama, and Chile, parasitizes numerous elasmobranchs, including angel sharks, leopard sharks, bat rays, and butterfly rays12,13,14,15,16. Beyond a single study demonstrating the hatching of cocoons of B. torpedinis Savigny, 18229 little is known of the reproduction and development of Branchellion species.

During the rearing of round stingrays at the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, newly birthed rays held in aquaria occupied by adult rays became infected with B. lobata. The ability of this leech to be transmitted in an aquarium setting provided an opportunity to study its development. In this paper, we describe the cocoons and morphology and experimental development of Branchellion lobata.

Methods

Sample collection and observations

Round stingrays (Urobatis halleri) infected with Branchellion lobata (Fig. 1) were collected by set line in Mugu Lagoon, Point Mugu Naval Air Station (Oxnard, CA) in accordance with a permit issued to R. Appy by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (S-200810003-20163-001 and amendments). Leeches were removed from stingrays which, with exception of two rays, were released at the site of capture. Two rays were held in captivity at 18 °C at the Cabrillo Beach Aquarium and subsequently infected by placing collected leeches into the tank holding the rays. After approximately 1 month, sandy substrate was collected from the tanks, and kept at 4–18 °C, until sorted. Cocoons, adhered to clusters of sand grains, were collected and later characterized by Leica stereomicroscope as either early stage, late stage (with a visible segmented leech inside), or empty, and preserved in 70% ethanol for molecular analysis. Cocoons in sediment with a high organic load more often failed to develop or died, thus the layer of sand during the initial collection and observation of cocoons was kept to a minimum thickness to prevent anoxia. Sand grains, not attached to cocoons, were also preserved in 70% ethanol for microbial analysis. Images were taken using a Pentax WG-III digital camera and measurements made in ImageJ software17. Healthy appearing cocoons were placed into clear, sterile petri dishes (100 × 15 mm) in 15 ml of filtered seawater and kept in an incubator at 18 °C. Leech ‘nurseries’ were checked daily and newly hatched leeches were preserved in either 70% ethanol, 4% paraformaldehyde or 3.5% formalin for molecular analysis, light microscopy, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), respectively. Cabrillo Marine Aquarium is accredited by the American Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and round rays were held with standards, programs and processes established by CMA in accordance with AZA standards and policies.

Branchellion lobata and the Pacific round ray (Urobatis halleri). A) Ray, with numerous attached Branchellion lobata (arrows) on the ventral surface, initially collected in Mugu Lagoon, Los Angeles, CA and held in captivity at 18 °C at the Cabrillo Beach Aquarium (San Pedro, CA). B) Branchellion lobata with blood filled stomach diverticula (SD), lateral diverticula of the intestine filled with digested blood (LD). Cephalic anterior sucker (aS), eyespots (E), proboscis (P), the male (♂) reproductive system, including ejaculatory duct and seminal vesicle, the female (♀) reproductive system (ovaries), branchiae (B), and caudal posterior sucker (pS). Photo taken with a Pentax Optio WG-III digital camera over a light box. Scale 3 mm.

Hatchling transmission to uninfected round rays

In order to study development and growth of leeches on round stingrays, sand containing cocoons was introduced into a small aquarium containing two juvenile stingrays birthed in captivity August 3, 2023 (held at 17–20 °C). Leech growth was monitored at irregular intervals over 74 days by photographing the ventral surface of infected rays. Leeches were measured in ImageJ, with reference to the known size of ray disc width.

Morphology

Cocoons, hatchlings, and adult leeches initially fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h, were rinsed in 1X phosphate buffered saline, and transferred to 70% ethanol. Specimens were rehydrated in 30% ethanol, and stained with either Grenacher’s Alcoholic Borax-carmine or Celestine Blue B. Specimens were de-stained in 70% acid alcohol, dehydrated through a graded series of 85–95–100% ethanol, and cleared with methyl salicylate. Specimens were mounted in Canada balsam and visualized on a Nikon E80i microscope. Additional images were taken with a Pentax Optio WG-III digital camera. For SEM, preserved juvenile leeches and cocoons were post-fixed in 4% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in an ethanol series and critical point dried using CO2, and placed on stubs covered with adhesive copper tape. Specimens were coated with gold/palladium using an Pelco SC-4 4000 sputter coater and imaged using a Phenom Pro’X G6 Desktop SEM.

DNA extraction and Bacterial 16S rRNA sequencing

DNA was extracted from pooled sand grains, cocoons, and hatchlings (4–8 in each DNA extract) using the Qiagen DNeasy Kit, according to the manufacturer's recommendation, and quantified using a QuBit fluorometer. The V4-V5 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was PCR amplified using bacterial primers (515F: GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA and 806R: GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT18) with Illumina adapters on the 5′ end (San Diego, CA, United States). Each PCR product was secondarily barcoded with Illumina NexteraXT index v2 Primers that included unique 8-bp barcodes, with NEB Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Mix at an annealing temperature of 66 °C for 11 cycles. Barcoded products were purified using Millipore-Sigma (St. Louis, MO, United States) MultiScreen Plate MSNU03010 with a vacuum manifold and quantified using the QuantIT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a BioRad CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System. Barcoded samples were combined in approximately equimolar amounts and purified again with Promega’s Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-up System, and quantified again using the QuBit system. This sample, usually 1500–3000 ng DNA total, was submitted to Laragen, Inc. (Culver City, CA, United States) for 2 × 250 bp paired-end analysis on the Illumina MiSeq platform with PhiX addition of 20%. Raw 16S rRNA reads were deposited in the NCBI archive under accession number PRJNA1088531.

Raw 16S rRNA reads were processed according to Happy Belly Bioinformatics19. Briefly, CutAdapt v4.1 was used to remove the primer sequences, which allowed one error for every 10 bp in the primer sequence20. FastQC v1.13 was used to quality control the raw sequence data and identify trim cutoffs for both the forward and reverse reads, ahead of pairing. Raw sequences were then processed with DADA2 (for initial quality trimming, error rate estimation, merging of read pairs, chimeric sequence removal, and community data matrix construction21) and taxonomy was assigned to the processed amplicon sequence variants (ASVs at 100% identity) using the SILVA database v138.122.

Blood deprivation experiments in adult Branchellion lobata

Adult Branchellion lobata (n = 15) were collected from the ventral surface of Urobatis halleri from Mugu lagoon, Los Angeles, CA, and kept in 400 ml glass containers with filtered seawater with a 12-h light cycle in an incubator at 18 °C. For 25 days, the number of surviving leeches was counted, weighed (wet weight–excess water was removed, as much as possible without harming the animal, by gently blotting on a kimwipe), and preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde. While in captivity, leeches were strongly photopositive when a host was not present, so it was necessary to add a layer of black tape to prevent them from climbing out of the water.

Ethical approval

Collection of round stingrays was conducted under permits SC-10578, SC-13105, and S-200810003-20163-001. Laboratory maintenance of stingrays was conducted at the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, accredited by the American Association of Zoos and Aquariums and per their animal care and management practice guidelines. Where applicable, methodological detail is provided in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Results and discussion

Branchellion lobata cocoons were found in abundance adhered to sand grains in a tank containing captive pacific round stingrays, Urobatis halleri, themselves heavily infected with B. lobata. Cocoons were readily sampled by agitation of the sand, which brought them to the surface. Deposition of cocoons was not observed, so it is not known whether adult leeches detach from their host to secrete the cocoons or if they deposit cocoons while still attached at a time when the ray is stationary on the bottom. Some piscicolid leeches (ex. B. torpedinis) remain on their host and release cocoons into the water9,23, whereas some detach to deposit cocoons on vegetation, abiotic substrates, or even other organisms2,7,8,10,24,25,26. The presence of up to 5 sand grains adhering to cocoons, and the morphology of the attached cocoon as viewed with SEM, suggests that they were actively placed on the sand grains (Fig. 2A-C). However, the absence of cocoons in jars containing mature (large) leeches would suggest that the leech remains attached to the host while depositing cocoons. Leeches often left the host and climbed the walls of the lighted side of the aquarium, perhaps due to anoxic conditions in the sediment at the bottom of the aquarium, but cocoons were never found attached to aquarium walls. Branchellion lobata held without a host immediately climbed the walls of the jar to the air water interface. This photopositive behavior may be an adaptation to facilitate encountering new hosts.

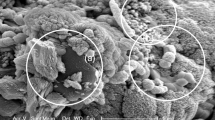

Development in Branchellion lobata, from cocoon to hatching. (A) Cocoon adhered to five sand grains. (B–D) Cocoons in various stages of apparent successive development. (D) Cocoon stained with carmine red, showing the leech embryo surrounded by albuminous fluid (arrowhead). (E) Developing leeches inside of cocoons. Note the segmentation (arrow). (F, G) Leech emerging from a cocoon. The arrow shows the cephalic sucker, with eyespots. (H, I) Leeches emerging from cocoons, imaged via scanning electron microscopy. Note the lack of both branchiae and pulsatile vesicles in the hatchling, compared to Fig. 3F. All scales, 0.5 mm, except I, scale = 0.2 mm.

Branchellion lobata cocoons measured 0.65 + /− 0.1 mm in diameter (x + /− SD; n = 13; Fig. 2), which is on the small end of the size range for cocoons of other piscicolids (0.5–20 mm in diameter7,27). B. lobata cocoons were found in various stages of development, including early stage, as shown by the carmine stained embryo inside the cocoon (Fig. 2D) and late stage with a visible segmented, often moving, leech inside (Fig. 2E-F). Cocoon incubation time was estimated to be at least 21 days, the time between sampling of sand grains from the captive rays to the first observed hatchling emergence. This is similar to the incubation time for B. torpedinis, documented at ~ 30 days9.

During hatching, a single translucent B. lobata emerged from each cocoon and pulled itself out by attaching its anterior sucker to nearby surfaces (Fig. 2G-H). Hatchlings measured ~ 2.5 + /− 0.4 mm in length on average (avg ± SD; n = 75), with a ratio of length to width of 12.5:1. This size at hatching is generally consistent with sizes reported for the piscicolids Oceanobdella microstoma Johansson, 1896 and O. blennii (~ 2–5 mm in length8,13, but smaller than Janusion scorpii Malm, 1863 (~ 4–12 mm6). By comparison, adult B. lobata are 13–40 mm in length, with a length to width ratio of ~ 8:1 (this study Fig. 3 and28).

Branchellion lobata external anatomy. (A) Adult, ventral surface. (B) Adult, dorsal surface. (C) Adult, cephalic sucker, dorsal view, with medial pair of eyespots (arrow). (D) Adult caudal sucker, ventral view, with numerous secondary suckers. (E) Adult, pulsatile vesicles (arrows), every 3 branchiae. (F) Late-stage juvenile, ventral surface showing foliaceous branchiae (arrowheads) and pulsatile vesicles (arrows), imaged via scanning electron microscopy. (G) Hatchling, ventral surface. (H) Hatchling, dorsal surface. Scale bars for A and B, 2 mm. Scale bars; C–E, 1 mm. F, 500 µm. G–H, 250 µm.

Newly hatched B. lobata strongly resemble the adults13, as do most marine leeches with direct development, with some exceptions. They possess two distinct body regions, the trachelosome and urosome, divided by a deep furrow (Fig. 4), originally described for adults28. The trachelosome includes a cephalic sucker that is flattened and circular, with a pair of dorsal pigmented eyespots, a muscular proboscis, and the male reproductive system (Fig. 4A-B). The urosome contains a pair of ovisacs, 5 pairs of testes that alternate with stomach diverticula, 4 posterior lateral diverticula of the intestine, and ganglia aligned along the testisacs and chambered stomach intestine (Fig. 4B-D). Posterior of the last lateral diverticula, there is an obvious rectum tapering to the anus (Fig. 4E). However, hatchlings lack the 31 pairs of conspicuous branchiae and pulsatile vesicles (Fig. 2I), characteristic of adult Branchellion species (Fig. 34,14,28,29). Like the adults, the hatchling caudal sucker was hemispherical, cupped, and nearly twice the size of the cephalic sucker, and it possessed many obvious small ventral secondary suckers, or cupules (Figs. 3, 4F28). Segmental ganglia, which in adults are obscured by internal organs, were prominent. Nephridia and cocoon glands were not visible in stained whole mounts. The new hatchlings obviously had no blood meal in their digestive system compared to the reddish-black blood meal observed in adults (Figs. 1,3).

Branchellion lobata Hatchling Histology. (A) Single pair of eyespots (collections of pigmented ocelli; blue arrow) on the dorsal side of cephalic sucker. (B) A pair of ovisacs (arrowhead). Also note the furrow separating trachelosome and urosome in this region (arrow at center). (C) The first pair of testes (arrowhead) and ganglia (arrow). (D) Lateral diverticula (arrowhead); there are 4 pairs posterior to the last pair of testes. (E) Rectum (arrow) and anus (arrowhead) located in the posterior end of the leech. (F) Secondary suckers (arrowhead, plus inset) located ventrally on the caudal sucker. Leeches were preserved in 4% PFA, rinsed with 1X PBS, stored in ethanol, and stained with celestine blue. Scale bar is 0.5 mm.

In general, leech hatchlings are precocious, but the timing of their first blood meal is highly variable4,9. For example, hatchlings of J. scorpii are able to survive without feeding for at least 3 weeks post emergence6 while young Hemibdella soleae van Beneden & Hesse, 1863 can survive without a host for two months5,30, instead relying on stored nutrients from the cocoon. By comparison, the young leeches of B. torpedinis were estimated to have just 5 days to find their first blood meal or they would not survive9. In the present study, the young leeches attached to the ventral surface of the rays, often in close proximity to one another in the area of the gill opening (not shown). Hatchlings took in blood meal, and quadrupled in length over a 74-day observation period, from ~ 2 to 8 mm, although they did not reach maturity as the rays died due to a system failure. These relatively slow growth measures are consistent with O. blennii, which took ~ 6 months to increase in length from 3 to 14 mm8. This, too, can be extremely variable among marine leeches. The marine leech J. scorpii matured within 48 days after emergence6, while Pterobdella arugamensis Silva, 1963 only took ~ 14 days post emergence to become mature31,32, both with access to a blood meal. For B. lobata, time to maturity (ex. viable reproductive organs) and specific fecundity (ex. how many cocoons can be deposited from a single B. lobata leech) were not determined, but development was noted to be relatively slow (> 74 days in experimental conditions).

Molecular analysis of the 16S rRNA bacterial gene allowed for a specific determination of the microbiomes for both B. lobata cocoons and hatchlings. The microbiome of the cocoons included an abundance of nitrogen-cycling bacteria and archaea (Nitrosopumilus, Nitrosomonas, and Nitrospina), Rhodobacteraceae and Saprospiraceae, all in near equal proportions, followed by Pirellulaceae and Rubritaleaceae, some also found in association with the sand grains (Fig. 5). The microbiome of the hatchlings, on the other hand, was found to be a subset of the Branchellion adult microbiome previously surveyed16,33, including the dominance of a specific, yet undescribed, member of the gammaproteobacteria (comprising ~ 66% of the average recovered ribotypes across all 4 hatchling samples; Fig. 5). Notably, amplification of this bacterium from the sand grains was unsuccessful, confirming that it is specifically associated with B. lobata and likely transmitted vertically from parent to offspring. Given its dissimilarity from all known bacteria (< 90% 16S rRNA gene identity to any known bacterial families), it remains an intriguing undescribed leech-associated microbe to explore in more detail. Additional bacterial groups associated with the hatchlings, but not present in the cocoons might be acquired by the hatchlings from environmental sources, such as seawater or biological surfaces, including Patescibacteria, Nitrincolaceae, Alteromonadaceae, and Marinomonadaceae (Fig. 5). The adult microbiome also included several of these bacterial groups, however, more research is needed to determine whether this potential microbe benefits the leech16.

The microbiome of Branchellion developmental stages. Relative abundance of bacterial families associated with Branchellion cocoons (n = 3 pooled samples), hatchlings (n = 4 pooled samples), and 1 sample of pooled sand grains (“rocks”), based on 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. The symbol sizes correspond to the relative abundance (%). The Shannon Diversity value for each type of sample is also shown.

In the present study, adult B. lobata removed from their elasmobranch host experienced a rapid decrease in body mass and did not survive beyond 25 days, with most dying within 11 days (80%, n = 15). During this period of time, leeches did not deposit cocoons, and became significantly smaller in average body mass (Fig. 6). By day 4 they had lost an average of 26% of their body mass, and by day-7 they had lost another 18%, significantly different from their starting weights (ANOVA p value = 0.037, f-ratio value = 5.3335). The requirement of B. lobata to feed frequently in order to survive is in stark contrast to terrestrial and freshwater leeches (ex. the medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis Linnaeus, 1758) that have slow digestion rates and feed very infrequently (every 8–10 months34). We suspect this may be a trend for marine leeches in general, where finding a host in a large habitat like the ocean is difficult, and staying attached, and feeding, is an effective strategy.

Adult Branchellion lobata without a blood meal for 25 days. At Day 0, there was obvious fresh blood in the stomach diverticula (arrowheads) and darker digested blood in the lateral diverticula. The bright red blood meal of newly fed B. lobata appears to move posteriorly and turns dark without replenishment of fresh blood anteriorly. By Day 8, there was very little observable blood meal, and the testisacs became most prominent on Day 12. Only 1 leech survived to Day 25, but was extremely small compared to leeches at Day 0. Photos taken with a Pentax Optio WG-III digital camera over a light box. Day 4 is a ventral view. All others are dorsal views. All scale bars, 1 mm.

While piscicolid leeches are infrequently associated with outbreaks and disease35, B. torpedinis has been listed as an emerging disease of elasmobranchs in aquaria23. Leeches can cause epidermal disruption and blood loss24,36, and the presence of even a single leech can result in humoral response in the host9. Similar to rays infected with B. torpedinis, heavily infected round rays in this study did not readily feed, were generally lethargic and in one case became anorexic and died (R. Appy, personal observation). Since there are few effective drugs against adult leeches and cocoons are difficult to treat or remove once deposited in the substrate23, we recommend mechanical removal of all leeches during quarantine35 to avoid any negative effects to the fish host in public aquarium exhibits.

Conclusion

The ability to raise the marine leech Branchellion lobata in captivity provided an opportunity to examine their reproductive strategy and development. During captivity, round stingrays (Urobatis halleri), became infected with B. lobata. Subsequently, cocoons were discovered adhered to sand grains in the aquarium substrate, and allowed to hatch. Young leeches had similar morphological features to the adults, except they lacked branchiae and apparent pulsatile vesicles. The microbiome of the hatchlings included a specific member of the gammaproteobacteria found also in the adult population. When introduced to naive ray hosts, also held in aquaria, hatchlings quadrupled in length over an observation period of 74 days, without becoming mature. While this study adds to our limited body of knowledge of marine leeches, difficulty of sampling the nomadic elasmobranch hosts of B. lobata continues to impact our understanding of the behavior, life history, and development of this common group of parasites.

Data availability

Raw 16S rRNA reads were deposited in the NCBI archive under accession number PRJNA1088531.

References

Mann, K. H. Leeches (Hirudinea): Their structure, physiology. Ecology and Embryology. Oxford: Pergamon Press (1962).

Sawyer, R. T. Leech biology and behavior (Vols. 1–3). Oxford University Press (1986).

Ko, D. H. & Lai, Y. T. On the origin of leeches by evolution of development. Dev. Growth Differ. 61, 43–57 (2019).

Burreson, E. M. Marine and estuarine leeches (Hirudinea: Ozobranchidae and Piscicolidae) of Australia and New Zealand with a key to the species. Invertebr. Syst. 34(3), 235–259 (2020).

Kearn, G. C. Leeches. Leeches, lice and lampreys: A natural history of skin and gill parasites of fishes. Springer Science & Business Media (2005).

Khan, R. A. & Meyer, M. C. Taxonomy and biology of some Newfoundland marine leeches (Rhynchobdellae: Piscicolidae). J. Fish. Board Can. 33(8), 1699–1714 (1976).

Light, S. F. The light and smith manual. Intertidal Invertebrates from Central California to Oregon. 4th Edition. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1001 p (2007).

Gibson, R. N. & Tong, L. J. Observations on the biology of the marine leech Oceanobdella blennii. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 49(2), 433–438 (1969).

Marancik, D. P., Dove, A. D. & Camus, A. C. Experimental infection of yellow stingrays Urobatis jamaicensis with the marine leech Branchellion torpedinis. Dis. Aquat. Org. 101(1), 51–60 (2012).

Becker, C. D. & Katz, M. Distribution, ecology, and biology of the salmonid leech, Piscicola salmositica (Rhynchobdellida: Piscicolidae). J. Fish. Board Can. 22(5), 1175–1195 (1965).

Narváez, K. & Osaer, F. The marine leech Branchellion torpedinis parasitic on the angel shark Squatina squatina and the marbled electric ray Torpedo marmorata. Mar. Biodivers. 47(3), 987–990 (2017).

Ruiz-Escobar, F. & Oceguera-Figueroa, A. A new species of Branchellion Savigny, 1822 (Hirudinea: Piscicolidae), a marine leech parasitic on the giant electric ray Narcine entemedor Jordan & Starks (Batoidea: Narcinidae) off Oaxaca Mexico. Syst. Parasitol. 96(7), 575–584 (2019).

Moser, M. & Anderson, S. An intrauterine leech infection: Branchellion lobata Moore, 1952 (Piscicolidae) in the Pacific angel shark (Squatina californica) from California. Can. J. Zool. 55(4), 759–760 (1977).

Burreson, E.M. Hirudinida. In The Light and Smith Manual. Intertidal Invertebrates from Central California to Oregon. (pp 303-309) 4th Edition. Los Angeles: University of California Press (2007).

Russo, R. A. Observations on the ectoparasites of elasmobranchs in San Francisco Bay California. Calif. Fish Game 99, 233–236 (2013).

Goffredi, S. K., Appy, R. G., Hildreth, R. & deRogatis, J. Marine vampires: Persistent, internal associations between bacteria and blood-feeding marine annelids and crustaceans. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1113237 (2023).

Abràmoff, M. D., Magalhães, P. J. & Ram, S. J. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophoton. Int. 11(7), 36–42 (2004).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108(Suppl 1), 4516–4522 (2011).

Lee, M. D. Happy Belly Bioinformatics: An open-source resource dedicated to helping biologists utilize bioinformatics. J. Open Source Educ 4(41), 53 (2019).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17(1), 10–12 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13(7), 581–583 (2016).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucl. Acids Res. 41, 590–596 (2012).

Dove, A.D.M., T.M. Clauss, D.P. Marancik & A.C. Camus. Emerging diseases of elasmobranchs in aquaria. In The Elasmobranch Husbandry Manual II: Recent Advance in the Care of Sharks, Rays and their Relatives. (eds. Smith, M, Warmolts, E. Thoney, R. Hueter, M. Murray & J. Ezcurra) 263–275 (2017).

Burreson, E. M. (2006). Phylum Annelida: Hirudinea as vectors and disease agents. In Fish Diseases and Disorders. Volume 1: Protozoan and Metazoan Infections (566–591). Wallingford UK: CABI.

Goffredi, S. K., Appy, R. G., Burreson, E. M. & Sakihara, T. S. Pterobdella occidentalis n. sp. (Hirudinida: Piscicolidae) for P abditovesiculata (Moore, 1952) from the Longjaw Mudsucker, Gillichthys mirabilis, and Staghorn Sculpin, Leptocottus armatus, and other fishes in the Eastern Pacific. J. Parasitol. 109(2), 135–144 (2023).

Ruiz-Escobar, F., Torres-Carrera, G., Islas-Villanueva, V. & Ocegurea-Figuroa, A. Molecular phylogeny of the leech genus Pontobdella (Hirudinida: Piscicolidae) with notes on Pontobdella californiana and Pontobdella macrothela. J. Parasitol. 110(3), 186–194 (2024).

Malek, M., Jafarifar, F., Roohi Aminjan, A., Salehi, H. & Parsa, H. Culture of a new medicinal leech: growth, survival and reproduction of Hirudo orientalis Utevsky and Trontelj, 2005 under laboratory conditions. J. Nat. Hist. 53(11–12), 627–637 (2019).

Moore, J. P. New Piscicolidae (leeches) from the Pacific and their anatomy. Occasional Papers of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum, 21(2), 17–44 (1952).

Meyer, M. C. The rediscovery together with the morphology of the leech, Branchellion ravenelii (Girard, 1850). J. Parasitol. 27(4), 289–298 (1941).

Llewellyn, L. C. Some aspects of the biology of the marine leech Hemibdella soleae. Proc. Zool. Soc. London 145, 509–527 (1965).

Kua, B. C., Azmi, M. A. & Hamid, N. K. A. Life cycle of the marine leech (Zeylanicobdella arugamensis) isolated from sea bass (Lates calcarifer) under laboratory conditions. Aquaculture 302(3–4), 153–157 (2010).

Azmey, S. et al. Population genetic structure of Marine Leech, Pterobdella arugamensis in Indo-West Pacific Region. Genes 13(6), 956 (2022).

Goffredi, S. K., Morella, N. M. & Pulcrano, M. E. Affiliations between bacteria and marine fish leeches (Piscicolidae), with emphasis on a deep-sea species from Monterey Canyon CA. Environ. Microbiol. 14(9), 2429–2444 (2012).

Phillips, A. J., Govedich, F. R. & Moser, W. E. Leeches in the extreme: Morphological, physiological, and behavioral adaptations to inhospitable habitats. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasit. Wildl. 12, 318–325 (2020).

Hadfield, C. A. & Clayton, L. A. Elasmobranch Quarantine. In The Elasmobranch Husbandry Mannual II: Recent Advances in the Care of sharks, Rays and their Relatives (eds Smith, M. et al.) 113–133 (Ohio Biological Survey Inc, 2017).

Noga, E.J. Fish disease: Diagnosis and treatment. 2nd Edition. Wadsworth Publishing (2010).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was made possible by a National Science Foundation grant to SG (IOS-1947309). The authors would also like to thank Jeff Landesmand and Carin Latino (Cabrillo Marine Aquarium) for animal husbandry, Bianca Dal Bó for assisting in the molecular analysis, and the Occidental College Undergraduate Research Center and generous donations by Ron and Susan Hahn for student support. Collection of round stingrays was conducted under permits SC-10578, SC-13105, and S-200810003-20163-001. Special thanks to Martin Ruane, U.S. Navy, Point Mugu Air Station for providing access to Mugu Lagoon to catch round stingrays.

Funding

Funding for this project was made possible by a National Science Foundation grant to SG (IOS-1947309).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception, design, data collection and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by A.L. All authors edited previous versions of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lizarraga, A., Appy, R. & Goffredi, S.K. Life cycle and development of the marine leech Branchellion lobata (Hirudinea: Piscicolidae), from round stingrays, Urobatis halleri, from southern California. Sci Rep 14, 18108 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69078-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69078-z