Abstract

Nonlinear optics (NLO) and its applications have attracted increasing research interest in recent years owing to their contribution to the development of photonic technology. Accordingly, in this study, we investigated the NLO response of pumpkin seed oil using the spatial self-phase modulation (SSPM) method. Significant NLO characteristics have been experimentally studied at \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) continuous wave (CW) laser wavelengths, yielding second-order nonlinear refractive index (\(n_{2,\,th}\)) values of \(6.54 \times 10^{ - 5} \,{{{\text{cm}}^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{cm}}^{2} } W}} \right. \kern-0pt} W}\) and \(2.73 \times 10^{ - 5} \,{{{\text{cm}}^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{cm}}^{2} } W}} \right. \kern-0pt} W}\), respectively. The findings suggest that the absorption of the material leads to higher optical nonlinearity at shorter wavelengths owing to higher thermal effects. Furthermore, we implemented a light-controlled-light system based on the spatial cross-phase modulation (SXPM) technique employing pumpkin seed oil. We successfully achieved all-optical switching by designing the 'ON' and 'OFF' modes. The results of this study can be considered for the future development of NLO applications. Moreover, our work investigates the potential of pumpkin seed oil for designing low-cost and high-efficiency NLO devices, and this contribution opens up a novel practical avenue for oil-based optical devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonlinear optics (NLO) phenomena were first observed in the early 1960s, with the discovery of lasers by Maiman. These phenomena describe the interaction between intense coherent light and a nonlinear medium1. NLO has reached an advanced level, proven to be an interesting field, and has played a very important role in advancing photonic technologies2. NLO has produced and developed many optical devices that are essential to our daily lives. Moreover, it is the source of several important applications such as all-optical switching, all-optical modulation, all-optical diodes, optical limiting, optical computing, and many others3,4,5,6,7,8. However, the advantages of all-optical devices that provide higher speed at a lower cost, smaller size, and lower loss are expected to displace all-electronic devices in communication, computing, and many other areas9. Therefore, researchers are actively seeking and introducing materials with significant NLO behavior for potential use in this industry. Currently, several techniques are used to measure the NLO parameters of various materials, including four-wave mixing, interference method, Z-scan, Mach–Zehnder interferometry, and spatial self-phase modulation (SSPM) techniques, with good agreement between the results obtained from these techniques10,11,12.

The SSPM method is widely employed to investigate the optical nonlinearity of materials because it has a simple experimental setup, provides accurate measurements, and does not require complex calculations. It is also associated with a physical mechanism related to thermally induced nonlinearity or optical Kerr nonlinearity2,13. Typically, the SSPM effect occurs when a strong Gaussian light beam interacts with NLO medium. The refractive index of the medium changes owing to this interaction. This causes a phase change (or phase modulation) in the laser beam that impinges on the medium, thereby creating a ring-shaped diffraction pattern14. Ultrafast laser pulses and continuous-wave lasers can be used to explore nonlinear optical responses of different materials. In their studies, Rui Wu and co-workers demonstrated that graphene sheets in solution dispersion have remarkably high optical nonlinearity using ultrafast laser beams and near-infrared, visible, and ultraviolet continuous waves15. It was believed that the strong interaction of the laser with these materials, which have high third-order nonlinearity, generated ring patterns from the diffraction of laser light by spatial self-phase modulation in liquid suspensions of 2D nanomaterials. In addition, continuous lasers were used to study the NLO response of several materials, including liquid suspensions of 2D nanomaterials16, solutions of fullerenes17, MoSe2 nanosheets18, and suspensions of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenides19. Among recent works, Wang and co-workers challenged the concept that SSPM in liquid suspensions of 2D materials under continuous-wave illumination was based on third-order nonlinear susceptibility (\(\chi^{3}\))15. Variations in the refractive index have been found in the case of using a continuous light source, where thermal effects are induced by laser light13,14,20. In this regard, the thermal effect and heat accumulation on the materials have significant consequences for their nonlinear optical properties, which can also be induced by exposure to single laser pulses with a high repetition rate. Even at an energy level as low as nanojoules (\(nJ\)), high-repetition-rate femtosecond pulses may cause significant thermal effects, leading to an extensive thermo-optic nonlinear refractive index. This is especially applicable to materials with high absorption coefficients, such as graphene21. Therefore, the thermal effect is intrinsically correlated with the material's light absorption capacity. As the material's absorption of light energy intensifies, the resultant heating rises, leading to significant changes in the refractive index.

The SSPM technique has many similarities to the Mach–Zehnder interferometer. Due to its precise light measurement and manipulation capabilities, the Mach–Zehnder interferometer enables the investigation of nonlinear phenomena and the development of advanced optical devices for applications such as all-optical switching, logic gates, frequency conversion, and modulation22,23. Similarly, the SSPM method is not only useful and practical for characterizing the NLO behavior of materials but also plays an important role in optical switching and modulation. Therefore, many studies have applied this technique to test materials for various NLO and photonic device applications2,24,25. To investigate the operation of optical switches and other photonic devices based on the light-modulation-light process, the dual-beam SSPM method was employed. This technique is known as spatial cross-phase modulation (SXPM)26. Using this technique, a weak probe light experiences an additional phase modulation induced by another powerful pump light. This process results in the simultaneous formation of diffraction ring patterns for both pump and probe beams simultaneously27. According to the fundamental principles of light propagation, when two beams of light intersect in space, they usually do not interact, but rather remain in their respective paths of propagation. However, in a light-controlled-light system (all-optical switching), it is possible to make these different light beams interact with each other using materials that have a strong NLO response. The optical switching process is performed based on the principle of controlling the light with another light. This device can convert or perform logical operations on optical signals within an optical network or integrated optical system28. High optical nonlinearity enables rapid and reversible switching between states for all optical signal parameters such as frequency, phase, power, and polarization. Furthermore, the significance of optical switching devices in the design and development of all-optical systems such as all-optical information conversion29, optical computing systems2, and optical communication networks30, has made them an important research topic. The first light-modulation-light system based on SSPM was developed by Yanling Wu and co-workers31, where they used MoS2 was used as the NLO medium. Several other studies have reported the design of all-optical switchers based on SXPM that take advantage of different materials, including few-layer bismuthene26, few-layer Tin Sulfide32, MXene33, 2D TaSe2 nanosheets34, pyrromethene-56727, and many more. Furthermore, in the search for different materials with high NLO behavior that can be used in NLO applications, recent studies have shown that various organic materials35, crocin36, Congo red37, 2D materials2, acid blue 2938, liquid crystal39, and many others have high NLO properties. In our previous study, edible oils such as cherry seed oil, avocado seed oil, and sesame oil showed a high NLO response8.

In this study, we employed the SSPM technique to examine the oil under a continuous laser beam at wavelengths of \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(532\,{\text{nm}}\). In addition, as a convenient and economical sample of a nonlinear all-optical switching/modulation application, we examined pumpkin seed oil using two continuous laser beams at wavelengths of \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(633\,{\text{nm}}\) as the pump and probe light beams, respectively. The findings presented in this contribution show that pumpkin seed oil exhibits considerable NLO behavior, wherein optical nonlinearity is higher at \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelength than at \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelength. Furthermore, we found that incorporating the SXPM into pumpkin seed oil allows the realization of optical switching/modulation caused by two continuous laser beams, which could be an interesting candidate for the development of nonlinear photonic devices.

Materials and methods

In the present study, the experimental sample was virgin pumpkin seed oil, which is commonly used in the health food, food marketing, and cosmetic industries as an edible vegetable oil. This oil is rich in essential fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, natural proteins, omega 3, 6, and 9, and vitamins. It contains minerals such as Zn, Fe, Mg, and Se40,41. Commonly, high-quality pure edible oils are extracted by mechanical cold pressing without the use of chemical solvents or heating processes42,43. Herein, for pumpkin seed oil extraction, we applied this technique, in which pumpkin seeds were pressed under high pressure using a suitable mechanical pressing machine.

Then, using the prepared oil sample, an absorption spectrum was obtained to analyze the light absorption of the pumpkin seed oil within the visible spectral range of \(380 - 750\,{\text{nm}}\). The absorption measurements were performed on a PHYSTEC-UVS-2500 spectrometer with a \(10\,{\text{mm}}\) path length cuvette. As seen in Fig. 1, the pumpkin seed oil sample exhibited considerable absorbance, especially in the \(400 - 600\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelength region. From this figure, we can determine the absorption coefficient values (\(\alpha_{0}\)) of the pumpkin seed oil sample at \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelengths, which are measured to be \(1.5\, \text{cm}^{ - 1}\) and \(1.55\,\text{cm}^{ - 1}\), respectively. It is important to note that the light absorption spectrum of each oil sample depends on the composition of the fatty acids and other components in the oil. However, the amount of fatty acid components determines the absorption level44.

The NLO behavior of pumpkin seed oil was examined using the SSPM technique. Previous studies have demonstrated that the SSPM phenomenon depends on a wide range of factors, including molecular reorientation45, third-order susceptibility effects2,46, and thermo-optical effects19. When the SSPM is due to the electronic polarization or molecular orientation of NLO materials, it can be related to the real part of the third-order susceptibility10. In this case, the measurement of \(n_{2}\) through the analysis of SSPM patterns allows for the measurement of \(\chi^{3}\). This can be achieved by using ultrafast pulse lasers. However, a continuous-wave laser does not provide sufficient time for the system to relax thermally. Hence, the observed diffraction ring pattern could not be explained because of the inherent electronic NLO effect of the samples. As described in Ref.16, when the SSPM is caused by thermal effects, the relationship between the nonlinear refractive index (\(n_{2}\)) and third-order susceptibility (\(\chi^{3}\)) is often inaccurate. In this case, the medium experiences localized heating and thermal effects owing to the intensity of the laser beam. Optical materials with a high thermo-optical coefficient undergo significant changes in their nonlinear refractive index20,47. The relative phase shift of a cylindrically symmetric Gaussian beam propagating in a liquid sample is approximated by48:

where \(\Delta \phi \left( r \right)\) is symmetric with respect to the axis at \(r = 0\) and \(\Delta nkL_{eff} = \Delta \phi \left( 0 \right)\), \(\Delta n\) represents the average change in refractive index, \(k\) is the wave vector, \(L_{eff}\) is the effective length of the sample, \(a\) is the constant that determines the extent of phase shift, and \(\Delta \phi \left( 0 \right)\) is the corresponding phase shift. Because of the symmetric nature of \(\Delta \phi \left( r \right)\), interference can occur between the radiation fields at two different radial positions, \(r_{1}\) and \(r_{2}\), having the same wave vector. Constructive interference (bright rings) or destructive interference (dark rings) occurs when \(\phi \left( {r_{2} } \right) - \phi \left( {r_{1} } \right) = m\pi\), where \(m\) is an even or odd integer. When \(\Delta \phi \left( 0 \right) > 2\pi\), multiple diffraction rings are expected to be observed. The number of observable rings (\(N\)) can be correlated with the phase shift \(\Delta \phi \left( 0 \right)\) and can be estimated using Eq. 49:

Since, the correlation between \(\Delta n\) attributed to thermal effects \(\Delta n_{th}\) and incident on-axis laser intensity \(I\left( 0 \right)\) may be expressed as follows19:

where \(n_{2,\,th}\) is the effective nonlinear coefficient and the subscript "th" refers to its thermal origin. Thus, using Eq. (2) and the relationship between the number of concentric rings \(N\) and the incident beam intensity \(I\left( 0 \right)\), we can derive an estimation for the \(n_{2,\,th}\) based on the nonlinear phase shifts, which are expressed as:

Using Eq. (2) and Eq. (3), the nonlinear refractive index \(n_{2,\,th}\) is given by19,47:

As mentioned previously, the variable \(N\) represents the number of SSPM fringes and \(\lambda\) denotes the wavelength of the laser used in the experiment. Additionally, \(I = {{2P_{average} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{2P_{average} } {\left( {\pi \omega^{2} } \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {\pi \omega^{2} } \right)}}\) represents the intensity of the laser beam where \(\omega\) is the computed beam radius at the cuvette’s entrance. In this relation, the focalization of the beam was accounted for by taking \(\omega\) as the radial distance from the axis where the intensity is reduced to \({1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {e^{2} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {e^{2} }}\) of its maximum value. On the other hand, when the cuvette length (\(L\)) is smaller than the estimated Rayleigh length (\(z_{R}\)), and the sample is placed in front of the laser in the Rayleigh range, the beam spot remains approximately constant. In this case, assuming a reasonably collimated beam passes through the sample with a nearly constant transverse area within the cuvette length, \(L_{eff}\) can be determined by the linear absorption of the samples (\(\alpha_{0}\)) and the length of the sample’s cuvette (\(L\))19:

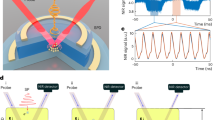

The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2a. We used two continuous laser beams at the wavelengths of \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) individually as light sources to radiate the oil sample. The laser beams were focused on a quartz cuvette containing the sample after passing through a convex lens with a focal distance of \(100\,{\text{mm}}\). The thickness of the cuvette cell was selected based on the transmittance of laser light and the Rayleigh range, which was smaller than the Rayleigh length. We estimated the Rayleigh length (\(z_{R} = {{\pi \omega_{0}^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\pi \omega_{0}^{2} } \lambda }} \right. \kern-0pt} \lambda }\)) to be approximately \({19}{.4}\text{mm}\) and \(62 \, \text{mm}\) for both \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beams used, respectively, where \(\omega_{0}\) refers to the beam waist at the focal point. For a laser wavelength of \(532\,{\text{nm}}\), a cuvette thickness of \(10\,{\text{mm}}\) was used. While for the wavelength of \(405\,{\text{nm}}\), a thickness of \(1\,{\text{mm}}\) was selected. This difference in cuvette thickness is attributed to the difference in the waist (\(\omega\)) of the laser beams at the cuvette's entrance, where the \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) laser wavelength beam waists are \(55\,\mathrm{\mu}{m}\) and \(168\,\mathrm{\mu}{m}\), respectively. This indicates that the \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beam is more concentrated than the \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beam, which raises the \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) beam's intensity in the sample. Consequently, the \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beam is more effective at inducing thermal effects within the sample, as the heat generated is more concentrated in the smaller sample volume. This concentration can create a sufficient temperature gradient, leading to significant variations in the refractive index and subsequently forming the SSPM ring pattern. Conversely, the energy of the \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beam is distributed over a larger area when a \(1\,{\text{mm}}\) cuvette thickness is used, resulting in lower temperature gradients and diminished thermal effects. In this case, the variation in the refractive index is insufficient to form SSPM ring patterns. Therefore, we selected a thicker cuvette to provide a longer path length for the laser beam. This increased path length allows the material to absorb more of the beam's energy, leading to greater overall heating. As a result, this enables a more substantial change in the refractive index, facilitating the formation of SSPM ring patterns. In Table 1, the computed values of the experimental parameters are presented.

In another phase of our experiment, the pumpkin seed oil sample was studied for NLO switching application using the SXPM method. To achieve this, we selected two laser beams and combined them to simultaneously irradiate pumpkin oil samples. The first beam (Diode laser-\(405\,{\text{nm}}\)) as pump beam, had a wavelength, that falls within a spectral range that is highly absorbed. The second beam (He–Ne laser-\(633\,{\text{nm}}\)) acts as a probe beam which falls within a spectral range where our samples exhibit very low absorption. The light beams, pump, and probe were positioned at similar heights to ensure that they passed through the same point of the pumpkin seed oil sample. The sample was placed in a quartz cuvette with a thickness of \(1\,{\text{mm}}\). The laser beams were focused through two identical lenses with a \(100\,{\text{mm}}\) focal point. The diffraction ring patterns that appeared on the screen located behind the sample were captured using a digital camera (Camera EOS Kiss X50). Figure 2b shows the arrangement diagram for this technique.

Results and discussion

Optical nonlinearity of pumpkin seed oil

Nonlinear refractive index of a NLO medium is wavelength-dependent due to changes in the absorbance of the medium at different wavelengths. The higher the absorbance, the higher the energy of light absorbed, and hence, the increased thermal effects and more localized heat produced within the medium. However, the intensity and power of the laser directly contribute to the appearance of the NLO response. Therefore, this is a crucial factor in the formation of SSPM patterns and an increase in the number of rings. In this study, as mentioned earlier, we employed both \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) continuous lasers to investigate the NLO behavior of pumpkin seed oil in the thermal regime. Figure 3 shows the SSPM diffraction ring patterns as a function of the input power for both laser beams. As evident from Fig. 3a① and Fig. 3b①, no rings were observed for the laser beams \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(405\,{\text{nm}}\), respectively. This can be attributed to the laser power being below the threshold power/intensity required to induce a phase shift to generate the first ring. According to Eq. (4), the threshold intensity is the minimum required intensity for \(\Delta \phi = 2\pi\) and observing the first diffraction ring with \(N = 1\). Additionally, it is worth noting that intensities below the threshold intensity do not provide sufficient values to induce a nonlinear response and generate SSPM phenomena. In other words, Eq. (5) is only applicable for incident intensities that exceed the threshold intensity. In NLO materials that exhibit a stronger nonlinear response, lower threshold energy values are required to observe the first SSPM diffraction ring. Upon reaching the threshold intensity, the first SSPM ring appeared. The number and size of the rings increased progressively with further increments of laser power as shown in Fig. 3a② and Fig. 3b②. When the laser power increases from \(10.7\,\) to \(52.3\,{\text{mW}}\) for \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) and from \(4.5\,\) to \(28.4\,{\text{mW}}\) for \(405\,{\text{nm}}\), a pattern called SSPM begins to emerge on the screen. This pattern gradually grew in size, consisting of many small rings. The intensity of the outermost ring was the highest, and the intensity of the inner rings decreased steadily as the rings moved towards the center of the pattern. This is because the outermost ring was created by the interference of light waves at the maximum slope (at inflection points) of the Gaussian curve. It is worth noting that the ring patterns were formed in the same shape as the cross-sectional incident laser beams.

In addition, the smaller incident laser beam wavelength (\(405\,{\text{nm}}\)) results in more rings forming at the same power compared to the larger wavelength (\(532\,{\text{nm}}\)). This demonstrates the impact of the excitation laser wavelength on the appearance of NLO behavior and SSPM ring patterns. Additionally, according to Song and co-workers in their research50, the dependency of the increase in the number of diffraction rings on the intensity/power can be justified by the Gaussian profile of the laser beam. After passing through a nonlinear medium, a Gaussian beam exhibits a phase shift, represented by a curved graph with a Gaussian shape. In this graph, the positions with the same slope exhibit coherence. The position with the highest slope in the graph indicates the number of diffraction rings. The highest slope position can be further shifted by increasing the intensity/power of the light source. Consequently, the number of rings formed increases.

From Eq. (5), in order to measure the second-order nonlinear refractive index \(n_{2,\,th}\), it is necessary to measure the \({N \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {N I}} \right. \kern-0pt} I}\) parameter. The \({N \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {N I}} \right. \kern-0pt} I}\) parameter represents the slope of the number of diffraction rings \(N\) plotted against the laser beam intensity \(I\). Figures 4a and 4b, show the variation of \(N\) against \(I\) for both employed wavelengths employed. As shown in these figures, we observe that the threshold intensity for both \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelengths is \(26.5\,{W \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {W {cm^{2} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {cm^{2} }}\) and \(24.15\,{W \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {W {cm^{2} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {cm^{2} }}\), respectively. The obtained values of \({{dN} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{dN} {dI}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {dI}}\) and \(n_{2,\,th}\) for the examined pumpkin seed oil sample at both wavelengths are presented in Table 1. At both wavelengths, we measure a high \(n_{2,\,th}\) value of order \(10^{ - 5}\) for the sample. These significant values can be attributed to the high localized light absorption of the sample in the visible spectrum. The high localized absorption implies that the material effectively absorbs incident photons, leading to significant thermal effects and the generation of localized heat. Consequently, a temperature gradient is produced due to excess thermal energy that raises the medium's temperature. This heating effect induces a considerable change in the refractive index (\(\Delta n_{th}\)) through the thermal effect, which is directly affected by the temperature gradient inside the material. Therefore, the higher the absorption capacity, the more changes occur in the sample's refractive index. Further, from Eq. (3), the relationship between \(n_{2,\,th}\) and \(\Delta n_{th}\) is directly proportional; with increasing \(\Delta n_{th}\), optical nonlinearity rises, confirming the higher nonlinear refractive index (\(n_{2,\,th}\)).

Relationship between the number of rings and the incident laser intensity of the laser beam at different wavelengths: (a) \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) and (b) \(405\,{\text{nm}}\). The solid lines represent the linear relation, and the corresponding slopes directly yield the second-order nonlinear refractive index \(n_{2,\,th}\) for different wavelengths.

On the other hand, Fig. 4 clearly demonstrates that there is a noticeable difference in the slopes of the lines at the \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelengths. It is important to highlight that the slope for the \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelength is smaller than that for the \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelength. This difference can be related to the effective length of the sample, which is \(0.93\,{\text{mm}}\) at the \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelength and \(5.07\,{\text{mm}}\) at the \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelength. According to the correlations we mentioned earlier, as the effective length increases, the value of \(\Delta \phi\) rises, resulting in the formation of additional rings within a specific laser intensity range, thereby leading to an increase in \({{dN} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{dN} {dI}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {dI}}\). Additionally, it is interesting to note that the value of \(n_{2,\,th}\) in Table 1 indicates that the optical nonlinearity of the pumpkin seed oil sample is higher at the \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelength than at the \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelength, although the sample's absorption is very close at both wavelengths. This result can be attributed to the greater effectiveness of the \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beam in inducing a thermal effect on the material compared to the \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beam, which generates more heat in a given sample volume. Table 2 provides a comparison of the nonlinear refractive index values of pumpkin seed oil obtained in this study with those of other recently reported samples. The results obtained show that the pumpkin seed oil sample has a higher nonlinear refractive index at both \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(532\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelengths compared to some other samples. This difference could be due to the significant absorbance of the pumpkin seed oil sample at these wavelengths, which we attribute to its substantial fatty acid content41,43,44. In contrast, the value of \(n_{2,\,th}\) for pumpkin seed oil is relatively lower than the samples reported in Ref.33 and Ref.51. This can be attributed to the lower heat generated in the pumpkin seed oil samples compared to the samples containing the 2D materials mentioned in these references. Furthermore, in Table 3, we compare our results with those presented in the studies using the Z-scan technique. These studies generally reported second-order nonlinear refractive index values within a comparable range to our findings.

Optical switching based on pumpkin seed oil

Optical switching works based on NLO principles, and materials that exhibit high NLO responses could be used for the realization of optical switches28. The SXPM method is frequently used to design and study optical switching26,32. As mentioned earlier, this method operates through the same NLO mechanism as the SSPM method. In this method, two laser beams (pump and probe) of different wavelengths are merged to irradiate a sample that exhibits NLO behavior. Herein, we conducted an experimental examination of the light-controlled-light technique in our study using pumpkin seed oil as the main experimental component. Initially, for this purpose, we set the \(633\,{\text{nm}}\) laser power at \(3.53\,{\text{mW}}\); here, as shown in Fig. 5a, only the red laser spot can be observed on the screen. Simultaneously, we passed the intense pump laser (\(\lambda = 405\,{\text{nm}}\), violet color) with sub-threshold power through the sample, which appears as a violet Gaussian spot on the screen, as shown in Fig. 5b. Subsequently, with increasing pump laser power (\(P_{pump}\)), the SSPM diffraction ring patterns immediately for the pump and probe beams are formed together. As illustrated in Fig. 5c①, when the power of the pump laser beam reached the threshold value (\(P_{pump} = 4.99\,{\text{mW}}\)), the first ring was concurrently generated for both lasers. With a continuous increase in laser pump power, the number of rings and sizes of the patterns gradually expanded; refer to Figs. 5c (② and ③). It can be observed that there are fewer red diffraction rings in comparison to the violet rings, which could be attributed to the lower power and photon energy of the \(633\,{\text{nm}}\) probe beam.

(a) Snapshot of the probe laser beam spot (\(\lambda = 633\,{\text{nm}}\)). (b) Snapshot of the pump laser beam spot (\(\lambda = 405\,{\text{nm}}\)). (c) Diffraction ring pattern images for probe and pump laser beams together at three different pump beam powers. (d) Generation of diffraction ring patterns for the \(633\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beam by increasing the \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beam power, with a fixed \(633\,{\text{nm}}\) power below the threshold power. (e) Variation in the ring number of the probe laser beam controlled by the pump laser beam. It has been clearly shown that the probe laser power does not affect the results.

It is important to note that the weak power of the probe laser cannot excite the diffraction rings. Therefore, only the power of the pump laser can control the number of red probe laser rings. As shown in Fig. 5d, the visible diffraction ring patterns for the \(633\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beam are captured on the screen by filtering the passing \(405\,{\text{nm}}\) laser beam (i.e., filtering the violate ring patterns), where 12 rings are formed at the highest pump laser power used (\(P_{pump} = 27.7\,{\text{mW}}\)). Meanwhile, the red SSPM rings reveal the nonlinear phase variation of the probe beam. This variation is caused by the refractive index change of the nonlinear medium when the pump beam passes through it. It indicates that the phase of the incident probe signal is significantly modulated or controlled due to the influence of the powerful pump beam. Figure 5e illustrates the obvious linear relationship between the diffraction ring number of the probe beam \(N_{probe}\) and the intensity of the pump beam \(I_{pump}\). Further, we can point out that when we vary the power of the probe laser \(P_{probe}\), we consistently observe the same outcome. Thus, at different low probe powers, almost the same value for \({{dN_{probe} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{dN_{probe} } {dI_{pump} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {dI_{pump} }}\) was obtained. This result shows that the nonlinear phase variation of the probe is independent of the power of the probe laser (as long as it is at low powers that cannot excite the SSPM rings). Based on these results, it is apparent that pumpkin seed oil could be used to design all-optical switches using the SXPM effect. To understand this process, we attached a power meter to one of the outermost red bright rings in order to measure the power of the transmitted light from an aperture positioned in front of the red diffraction rings, as depicted in Fig. 6a. At a power level of \(P_{pump} = 15.1\,{\text{mW}}\), we recorded a bright ring power \(N = 6\) at \(P_{R} = 0.14\,{\mathrm{\mu}} W\). When we increased the power of the pump laser to a higher value \(P_{pump} = 16.5\,{\text{mW}}\), the power meter registered a drop on a dark ring. In this case, the power of the dark ring will be recorded at \(P_{R} = 0.05\,{\mathrm{\mu}} W\) with a corresponding change in the number of probe diffraction rings to 7 rings. Following this, the incident pump power keeps rising until it reaches \(18\,{\text{mW}}\), causing the detector to fall on the next bright ring and measure the maximum power again (\(P_{R} = 0.13\,{\mathrm{\mu}} W\)). By continuously increasing the pump laser power, the probe laser ring power undergoes periodic variation, as illustrated in Fig. 6b. These results demonstrate the significant potential of utilizing pumpkin seed oil in an all-optical switching application. Accordingly, the switcher will turn "ON" when the probe ring power received from the detector reaches its maximum value and "OFF" when it receives its minimum power. Furthermore, we believe that pumpkin seed oil is more effective than other previously reported materials3,33 for NLO switching because, based on the results, pumpkin seed oil is more efficient and has a higher degree of precision. As a result, within certain pump power ranges, it can perform a larger number of "ON" and "OFF" operations.

(a) Illustrates the positioning of a power meter on one of the outermost bright rings of a probe laser to measure the transmitted power of light from an aperture placed in front of probe diffraction patterns. (b) Realizing the all-optical switch by employing pumpkin seed oil based on controlling the probe beam by a pump beam to obtain “ON” and “OFF” modes.

Conclusion

In the present study, the spatial self-phase modulation (SSPM) technique was used to study the high optical nonlinearity of pumpkin seed oil. The second-order nonlinear refractive index was measured using a low-power continuous laser beam at \(\lambda = 405\,{\text{nm}}\) and \(\lambda = 532\,{\text{nm}}\) wavelengths in a thermal regime. From our experimental results, we show that the optical nonlinearity presents wavelength dependence, which could be attributed to laser-induced thermal effects due to the appearance of local heating phenomena. These effects are more pronounced at shorter wavelengths. The NLO properties of pumpkin seed oil were utilized to formulate a light-controlled-light system that resulted from the spatial cross-phase modulation (SXPM) effect. Such a system would allow the switching/modulation of an optical signal, whereby an intense pump beam controls the state of the weak probe beam and becomes an all-optical switch. In our investigation, we showed that pumpkin seed oil has the potential for efficient use in optical switching applications; therefore, the results are of great interest from an economic point of view for designing and conceiving NLO devices. These results suggest that the considerable development of all-optical devices is possible.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in this published article.

References

Boyd, R. W. The nonlinear optical susceptibility in Nonlinear Optics (Fourth Edition) (ed. Robert W. Boyd) 1–64 (Academic Press, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811002-7.00010-2

Wu, L. et al. Recent advances of spatial self-phase modulation in 2D materials and passive photonic device applications. Small 16, 2002252. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202002252 (2020).

Wu, L. et al. 2D Tellurium based high-performance all-optical nonlinear photonic devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806346. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201806346 (2019).

Chen, H., Wang, C., Ouyang, H., Song, Y. & Jiang, T. All-optical modulation with 2D layered materials: Status and prospects. Nanophotonics 9, 2107–2124. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0493 (2020).

Tang, J. et al. Broadband nonlinear optical response in GeSe nanoplates and its applications in all-optical diode. Nanophotonics 9, 2007–2015. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0531 (2020).

Tian, Y. B., Li, Q. H., Wang, Z., Gu, Z. G. & Zhang, J. Coordination-induced symmetry breaking on metal-porphyrinic framework thin films for enhanced nonlinear optical limiting. Nano Lett. 23, 3062–3069. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c00635 (2023).

Jiao, S. et al. All-optical logic gate computing for high-speed parallel information processing. OES 1, 220010. https://doi.org/10.29026/oes.2022.220010 (2022).

Hassan, A. N., Haddad, M. A., Golestanifar, M. & Behjat, A. Non-linear optical response as a food authentication: Investigation of non-linear optical properties of edible oils by spatial self-phase modulation (SSPM) method. Food Anal. Methods 16, 1392–1402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12161-023-02514-4 (2023).

Nozaki, K. et al. Sub-femtojoule all-optical switching using a photonic-crystal nanocavity. Nat. Photonics 4, 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2010.89 (2010).

Li, C. Optical kerr effect and self-focusing. In Nonlinear Optics: Principles and Applications (ed. Li, C.) 109–147 (Springer, Singapore, 2017).

Wu, L. et al. Kerr nonlinearity in 2D graphdiyne for passive photonic diodes. Adv. Mater. 31, 1807981. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201807981 (2019).

Boudebs, G., Sanchez, F., Troles, J. & Smektala, F. Nonlinear optical properties of chalcogenide glasses: Comparison between Mach-Zehnder interferometry and Z-scan technique. Opt. Commun. 199, 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0030-4018(01)01582-6 (2001).

Hassan, A. N., Haddad, M. A., Golestanifar, M. & Behjat, A. Investigating the nonlinear optical response of virgin cherry kernel oil and its application to detecting adulteration. Phys. Scr. 99, 075507. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ad5064 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. A review on spatial self-phase modulation of two-dimensional materials. J. Cent. South Univ. 26, 2295–2306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-019-4174-8 (2019).

Wu, R. et al. Purely coherent nonlinear optical response in solution dispersions of graphene sheets. Nano Lett. 11, 5159–5164. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl2023405 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. Distinguishing thermal lens effect from electronic third-order nonlinear self-phase modulation in liquid suspensions of 2D nanomaterials. Nanoscale 9, 3547–3554. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6NR08487G (2017).

Dengler, S., Azarian, A. & Eberle, B. New insights into nonlinear optical effects in fullerene solutions—A detailed analysis of self-diffraction of continuous wave laser radiation. Mater. Res. Express 8, 085702. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ac1c31 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Coherent nonlinear optical response spatial self-phase modulation in MoSe2 nano-sheets. Sci. Rep. 6, 22072. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22072 (2016).

Bautista, J. E. Q. et al. Intensity-dependent thermally induced nonlinear optical response of two-dimensional layered transition-metal dichalcogenides in suspension. ACS Photonics 10, 484–492. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.2c01598 (2023).

Bautista, J. E. Q. et al. Thermal and non-thermal intensity dependent optical nonlinearities in ethanol at 800 nm, 1480 nm, and 1560 nm. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 38, 1104–1111. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.418635 (2021).

Dey, S., Bongu, S. R., Sagar, V. K. & Bisht, P. B. Investigation of thermal nonlinearity due to nJ high repetition rate fs pulses on wrinkled graphene. JOSA B. 38, 2019–2026. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.420119 (2021).

Wu, Y. D., Huang, M. L., Chen, M. H. & Tasy, R. Z. All-optical switch based on the local nonlinear Mach-Zehnder interferometer. Opt. Express 15, 9883–9892. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.15.009883 (2007).

Taraphdar, C., Chattopadhyay, T. & Roy, J. N. Mach-Zehnder interferometer-based all-optical reversible logic gate. Opt. Laser Technol. 42, 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2009.06.017 (2010).

Ali, A. H., Sultan, H. A., Hassan, Q. M. A. & Emshary, C. A. Thermal and nonlinear optical properties of sudan III. J. Fluoresc. 34, 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10895-023-03312-1 (2024).

Shi, Y. et al. Spatial self-phase modulation with tunable dynamic process and its applications in all-optical nonlinear photonic devices. Opt. Lasers Eng. 158, 107168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2022.107168 (2022).

Lu, L. et al. All-optical switching of two continuous waves in few layer bismuthene based on spatial cross-phase modulation. ACS Photonics 4, 2852–2861. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.7b00849 (2017).

Thomas, T., Jayaprasad, K. V., Vijesh, K. R., Nampoori, V. P. N. & Vaishakh, M. Investigation of nonlinear optical response and all-optical switching/modulation in pyrromethene 567 based on spatial self-phase modulation. J. Opt. 25, 115401. https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8986/acf5fc (2023).

Xu, J., Peng, Y., Qian, S. & Jiang, L. Microstructured all-optical switching based on two-dimensional material. Coatings 13, 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings13050876 (2023).

Pan, Y., Lyu, Z. & Wang, C. All-optical switching in azo dye doped liquid crystals based on spatial cross-phase modulation. OSA Contin. 4, 2714–2720. https://doi.org/10.1364/OSAC.434765 (2021).

Dawes, A. M. C., Illing, L., Clark, S. M. & Gauthier, D. J. All-optical switching in Rubidium vapor. Science 308, 672–674. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1110151 (2005).

Wu, Y. et al. Emergence of electron coherence and two-color all-optical switching in MoS2 based on spatial self-phase modulation. PNAS 112, 11800–11805. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1504920112 (2015).

Wu, L. et al. Few-Layer Tin Sulfide: A promising black-phosphorus analogue 2D material with exceptionally large nonlinear optical response, high stability, and applications in all-optical switching and wavelength conversion. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6, 1700985. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201700985 (2018).

Wu, L. et al. MXene-based nonlinear optical information converter for all-optical modulator and switcher. Laser Photonics Rev. 12, 1800215. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201800215 (2018).

Shan, Y. et al. A promising nonlinear optical material and its applications for all-optical switching and information converters based on the spatial self-phase modulation (SSPM) effect of TaSe2 nanosheets. J. Mater. Chem. C 7, 3811–3816. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TC00333A (2019).

Ganeev, R. A., Boltaev, G. S., Tugushev, R. I. & Usmanov, T. Investigation of nonlinear optical properties of various organic materials by the Z-scan method. Opt. Spectrosc. 112, 906–913. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0030400X12060094 (2012).

Azarpour, A., Sharifi, S. & Rakhshanizadeh, F. Nonlinear optical properties of crocin: From bulk solvent to nano-confined droplet. J. Mol. Liq. 252, 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2017.12.141 (2018).

Hoseini, M., Sazgarnia, A. & Sharifi, S. Cell culture medium and nano-confined water on nonlinear optical properties of Congo red. Opt. Quantum Electron. 51, 144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-019-1865-1 (2019).

Ghanem, A., Zidan, M. D. & El-Daher, M. S. Diffraction ring patterns of the acid blue 29 in different solvents. Results Opt. 9, 100268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rio.2022.100268 (2022).

Al-Hamdani, U. J. et al. Optical nonlinear properties and all optical switching in a synthesized liquid crystal. J. Mol. Liq. 361, 119676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119676 (2022).

Shaban, A. & Sahu, R. P. Pumpkin seed oil: An alternative medicine. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 9, 11. https://doi.org/10.25258/phyto.v9i2.8066 (2017).

Siano, F. et al. Physico-chemical properties and fatty acid composition of pomegranate, cherry and pumpkin seed oils. J. Sci. Food Agric. 96, 1730–1735. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.7279 (2016).

Cakaloglu, B., Ozyurt, V. H. & Otles, S. Cold press in oil extraction. A review. Ukr Food J. 7, 640–654. https://doi.org/10.24263/2304-974X-2018-7-4-9 (2018).

Akin, G., Arslan, F. N., Karuk Elmasa, S. N. & Yilmaz, I. Cold-pressed pumpkin seed (Cucurbita pepo L.) oils from the central Anatolia region of Turkey: Characterization of phytosterols, squalene, tocols, phenolic acids, carotenoids and fatty acid bioactive compounds. Grasas y Aceites 69, 232. https://doi.org/10.3989/gya.0668171 (2018).

Puspita, I., Kurniawan, F., Hatta, A. & Koentjoro, S. Absorption spectra of edible oils on UV-visible-near infrared region. SPIE 11789, 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2587047 (2021).

You, J. W., Bongu, S. R., Bao, Q. & Panoiu, N. C. Nonlinear optical properties and applications of 2D materials: Theoretical and experimental aspects. Nanophotonics 8, 63–97. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2018-0106 (2019).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Two-dimensional atomic crystals. PNAS 102, 10451–10453. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0502848102 (2005).

Zidan, M. D., Al-Ktaifani, M. M., El-Daher, M. S., Allahham, A. & Ghanem, A. Diffraction ring patterns and nonlinear measurements of the Tris(2′,2-bipyridyl)iron(II) tetrafluoroborate. Opt. Laser Technol. 131, 106449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2020.106449 (2020).

Ogusu, K., Kohtani, Y. & Shao, H. Laser-induced diffraction rings from an absorbing solution. Opt. Rev. 3, 232–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10043-996-0232-1 (1996).

Durbin, S. D., Arakelian, S. M. & Shen, Y. R. Laser-induced diffraction rings from a nematic-liquid-crystal film. Opt. Lett. 6, 411–413. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.6.000411 (1981).

Song, C., Liao, Y., Xiang, Y. & Dai, X. Liquid phase exfoliated boron nanosheets for all-optical modulation and logic gates. Sci. Bull. 65, 1030–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2020.03.029 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Broadband third-order nonlinear optical responses of black phosphorus nanosheets via spatial self-phase modulation using truncated Gaussian beams. Opt. Laser Technol. 151, 108018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2022.108018 (2022).

Pramanik, A. et al. Synthesis, green photoluminescence and studies of nonlinear optical spatial self phase modulation effect in 2D Ga2Te3 nanosheets. ACS Appl. Opt. Mater. 1, 1634–1642. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaom.3c00119 (2023).

Wang, G. et al. Tunable nonlinear refractive index of two-dimensional MoS2, WS2, and MoSe2 nanosheet dispersions [Invited]. Photon. Res. 3, A51–A55. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.3.000A51 (2015).

Biswas, S. & Kumbhakar, P. Measurement of large nonlinear refractive index of natural pigment extracted from Hibiscus rosa-sinensis leaves with a low power CW laser and by spatial self-phase modulation technique. SAA 173, 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2016.09.049 (2017).

Alencar, M. A. et al. Large spatial self-phase modulation in castor oil enhanced by gold nanoparticles. SPIE 6103, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.647000 (2006).

Zamiri, R. et al. Investigation on nonlinear-optical properties of palm oil/silver nanoparticles. JEOS:RP 7, 12020. https://doi.org/10.2971/jeos.2012.12020 (2012).

Fontalvo, M., Garcia, A., Valbuena, S. & Racedo, F. Measurement of nonlinear refractive index of organic materials by z-scan. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 687, 012100. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/687/1/012100 (2016).

Marbello, O., Valbuena, S. & Racedo, F. J. Non-linear optical response of edible oils by means of the Z-scan technique. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1219, 012008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1219/1/012008 (2019).

Acknowledgements

"The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the team of the Research and Development (R&D) at Yazd Neshatavar Food Industry Company (Datis Co.) for their invaluable scientific guidance and support." "M. Ali Haddad dedicates this paper to Prof. Harold Linnartz, who passed away unexpectedly on New Year's Eve, 2023, at the age of 58. As the head of the Astrophysics Laboratory at Leiden Observatory, Prof. Linnartz made invaluable contributions to the field and inspired many with his passion and dedication. His legacy will continue to influence and guide the scientific community."

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. N. H. material preparation, data collection, prepared figures, analysed the results, wrote the main manuscript text, and writing review and editing. M. A. H. data collection, analysed the results, and writing review and editing. A. B. analysed the results, contributed to the investigation, and writing review and editing. M. G. material preparation, and writing review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, A.N., Haddad, M.A., Behjat, A. et al. Optical nonlinearity and all-optical switching in pumpkin seed oil based on the spatial cross-phase modulation (SXPM) technique. Sci Rep 14, 18158 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69170-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69170-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Exploring the thermal-induced optical nonlinearity of crude oil via spatial self-phase modulation technique

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Comparative study for the nonlinear properties of edible vegetable oils by using Z-scan technique

Journal of Optics (2024)