Abstract

Yaks live in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau for a long time where oxygen is scarce, but can ensure the smooth development of testis and spermatogenesis. The key lies in the functional regulation of the Sertoli cells under hypoxia. In this study, we sequenced yak Sertoli cells cultured in normal oxygen concentration (Normoxia) and treated with low oxygen concentration (Hypoxia) by whole transcriptomics, and screened out 194 differentially expressed mRNAs (DEmRNAs), 934 differentially expressed LncRNAs (DELncRNAs) and 129 differentially expressed miRNAs (DEmiRNAs). GO and KEGG analysis showed that these differential genes were mainly concentrated in PI3K-AKT, MAPK, RAS, and other signaling pathways, and were associated with glucose metabolism, tight junction, steroid hormone synthesis, cell fusion, and immunity of yak Sertoli cells. We constructed the gene interaction network of yak Sertoli cells in hypoxia and screened out the relationship pairs related to glucose metabolism and tight junction. The results suggested that the changes in energy metabolism, tight junction, and immune regulation of yak Sertoli cells under hypoxia might provide favorable conditions for spermatogenesis. This study provides data for further study on the role of non-coding RNA in testis development and spermatogenesis of yak.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypoxia has a significant negative effect on the reproductive ability of mammals and may cause oligospermia and low reproductive function in male animals, which is the most important factor restricting the fertility of humans and animals in high-altitude areas1,2,3,4. Studies have shown that hypoxia can significantly reduce the diameter of spermatogenic tubules and change the arrangement structure of spermatogenic cells5. The endocrine and microenvironment of the testis in hypoxic rats were changed, which led to abnormal development and even death of germ cells6,7. Sertoli cells are important cells in the microbiogenic environment, providing essential nutritional support for the development and differentiation of germ cells and spermatogenesis8. Hypoxia affects the development and differentiation of germ cells and spermatogenesis by regulating the gene expression of Sertoli cells. For example, it affects the expression of tight junction protein in Sertoli cells, damages the integrity of the blood-testis barrier, and reduces the proliferation of cells9,10,11.

With the wide application of omics sequencing in the study of animal reproductive regulation, testicular transcriptome data has been gradually improved. The transcriptomic results of mouse testis showed that 766 genes were up-regulated and 965 genes were down-regulated after hypoxic exposure, which caused irreversible damage to spermatogenesis6. miR-762 inhibited the expression of Ring finger protein 4 (RNF4) by binding to its 3 'UTR and blocked the activation of androgen receptor in the testis of Landrace pigs12. And miR-1285 can regulate the glycolysis of Sertoli cells and promote the proliferation of immature Sertoli cells13. Some recent studies have shown that the regulation of non-coding RNA plays an important physiological role in testicular heat stress, neodymium oxide exposure, testicular fusion, testicular endocrine homeostasis, and spermatogenesis14,15,16,17,18. However, the role of non-coding RNA in the regulation of testicular function in mammals with hypoxia is not clear.

Yaks, as a representative species of the Tibetan Plateau, offer a natural model for the study of hypoxia adaptation. The advent of omics technologies has markedly advanced this field in recent years. For instance, transcriptomic and proteomic analyses have been instrumental in examining the effects of hypoxia on yak pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells, shedding light on the cellular responses to hypoxia conditions19. Proteomics has further contributed to our understanding of yak testicular development, identifying key proteins involved in the spermatogenesis process20. A comparative multi-omics analysis has elucidated the genetic and proteomic disparities between yak and cattle-yak testicles, providing insights into the infertility mechanisms observed in cattle-yak hybrids21. Additionally, a whole transcriptomic study has pinpointed differential gene expression associated with the development and differentiation of Sertoli and Leydig cells within yak testicles22. Collectively, these studies underscore the pivotal role of omics technology in enhancing our comprehension of yak biology and its adaptation to high-altitude environments. At present, the application of omics technology in hypoxia-related studies mostly focuses on the lung, heart, kidney, mammary gland, ovary, and other organs of yaks23,24,25,26,27, and less on the testis, which is limited to development and differentiation.

Previous studies of our research found that compared with other cattle breeds living at low altitudes, yak testicles are smaller in weight and volume and have a tight distribution of blood vessels28,29,30, but their testicles can develop normally and ensure the occurrence and maturation of sperm after sexual maturity. Therefore, the problem of how to provide a stable condition for spermatogenesis in yak testis under hypoxia for a long time has aroused our concern. At present, most of the relevant studies on hypoxia regulation of male reproduction focus on human and model animals, while few reports have been reported in large mammals such as cattle and sheep. Moreover, the regulation of hypoxia on the microbiological environment of animals remains unclear. In summary, this paper analyzed the hypoxia response mechanism of yak Sertoli cells by whole transcriptomics, established the "non-coding RNA-mRNA" regulatory network of yak Sertoli cells under hypoxia, and explored the influence of hypoxia on yak spermatogenesis and the possible regulatory role of Sertoli cells in hypoxia. It provides a theoretical basis for the comprehensive analysis of the plateau adaptability mechanism of yak testis and the development of plateau reproductive medicine.

Results

Culture and identification of yak Sertoli cells

The primary yak Sertoli cells were cultured in vitro, and the adjacent cells were closely connected under the microscope, and the cells were integrated into sheets and spread into membrane-like monolayers. The cell grew well, and subsequent research could be conducted (Fig. 1A).

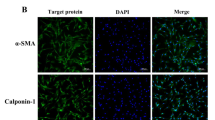

Culture and Identification of yak Sertoli cells. (A) Culture of yak Sertoli cells in vitro (100 ×). (B) Feulgen staining of yak Sertoli cells (100 ×). (C) Feulgen staining of yak Sertoli cells (400 ×). (D) Immunofluorescence staining of FASL and GATA4 in yak Sertoli cells under normoxia and hypoxia (200 ×). Red fluorescence: Target proteins, respectively. Blue fluorescence: cell nucleus.

The second generation of purified yak Sertoli cells was identified by Feulgen staining and indirect immunofluorescence staining, respectively. The results of Feulgen staining showed that the cytoplasm of the cells was light, the nucleus was dark, and purple particles were visible in the nucleus as special markers for Sertoli cells (Fig. 1B,C). Indirect immunofluorescence staining showed that marker proteins FASL and GATA4 were strongly expressed in cytoplasm and nucleus of yak Sertoli cells under normal and hypoxia, respectively, and the fluorescence intensity was basically the same, indicating that yak sertoli cells were successfully isolated and purified, and the cell properties remained unchanged under hypoxia (Fig. 1D).

Quality control of yak Sertoli cell samples

The results of the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer showed that the 6 yak Sertoli cell samples under normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (5% O2) did not degrade, the RIN value > 8.0, and the total RNA > 1 μg, which met the requirements of sequencing library construction. The results of RNA gel electrophoresis clearly showed three bands, indicating that samples were of good quality. It can be used for subsequent sequencing (Fig. 2).

Sequencing result

After sequencing, an average of 12.57 Gb of Raw reads were obtained per sample from the linear RNA library. Q20, Q30, mapped reads, and their ratios are shown in Table 1. The Raw reads of the raw Data were filtered, and the Valid Data Reads of the 6 samples were more than 10.50 Gb, respectively, and the Q30 was more than 97.30%. The mapping rate of filtered Clean reads was 91.87–92.21% when compared with the yak reference genome. Among them, the proportion of exon region, intron region, and intergene region were 41.53–47.9%, 40.92–47.43%, and 10.83–11.19%, respectively (Fig. 3A). The FPKM distribution box diagram was drawn according to the obtained gene expression levels (Fig. 3B), and the expression value density diagram (Fig. 3C) was made according to the value log10 (FPKM) after processing according to the respective expression levels of different samples. The results showed that the expression density diagram of all samples was in line with the normal distribution, the expression trend of biological duplicate samples tended to be consistent, the mRNA expression was relatively stable, as well as the quality of sequencing data was better in each group. The sequencing results of LncRNA showed that the length of most LncRNA and mRNA transcripts was more than 1000 bp, while the number of LncRNA transcripts with shorter lengths was more than mRNA (Fig. 3D). In addition, the number of LncRNAs was similar to mRNA, and its expression level was similar to mRNA, or even slightly higher than mRNA, indicating that LncRNAs played an important role in the functional regulation of yak Sertoli cells under hypoxia (Fig. 3E). The clean reads of each miRNA sequencing sample were no less than 9,751,553, and the Q30 was greater than 91.70% (Table 2). Figure 3F shows the length distribution of known miRNAs, most of which range from 21 to 23 nt and were dominated by 22 nt. Figure 3G showed that the conservative analysis of miRNA was highest in cattle.

Results of sequencing. (A) The ratios of mapped reads are located at different positions in the reference genome. (B) Samples FPKM box diagram. The X-axis is the sample name, and the Y-axis is log10(FPKM). (C) Expression value density plot. The X-axis is log10(FPKM) and the Y-axis is the density of the gene. (D) LncRNA and mRNA length statistics and comparison. (E) Statistics of LncRNA and mRNA expression levels. (F) The length distribution of known miRNAs. (G) Conservative analysis of miRNAs.

Differential gene expression analysis

A total of 194 DEmRNAs were identified by comparing the expression levels of genes in yak Sertoli cells in the normal oxygen group and the hypoxia group, among which 139 mRNA were up-regulated and 55 mRNA were down-regulated after hypoxia treatment (|1og2FC|≥ 1, P < 0.05). There were 934 DELncRNAs, of which 497 LncRNAs were up-regulated and 437 LncRNAs were down-regulated in the hypoxia group (|1og2FC|≥ 1, P < 0.05). There were 129 DEmiRNAs, of which 59 were up-regulated and 70 down-regulated (|1og2FC|≥ 1, P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A–C). The heat map showed the stratified clustering of samples (Fig. 4D–F), and the volcano map showed the differential expression of RNA between the yak Sertoli cells under normoxia and hypoxia (Fig. 4G–I).

DEmRNA, DELncRNA and DEmiRNA number statistics, Hierarchical clustering heat maps, and volcano maps. (A) Number of DEmRNAs. (B) Number of DELncRNAs. (C) Number of DEmiRNAs. (D) Heat map of DEmRNAs. (E) Heat map of DELncRNAs. (F) Heat map of DEmiRNAs. (G) Volcano map of DEmRNAs. (H) Volcano map of DELncRNAs. (I) Volcano map of DEmiRNAs.

The accuracy of the sequencing results was verified by q-PCR

A total of 12 mRNAs, 6 LncRNAs and 10 miRNAs were selected for relative expression detection. q-PCR detection results and FC values obtained by sequencing were respectively taken from the cells in the normoxia group and the hypoxia group, and their log values at the base of 2 were taken as the ordinate to draw the histogram (Fig. 5A–C), which directly reflected the expression level of the selected differential genes in the two groups of cells. The results showed that the relative expression of genes detected by qPCR showed the same trend as that by sequencing, which proved the reliability of full transcriptomic sequencing data and could be further analyzed and verified.

GO and KEGG analysis

GO functional annotation includes three categories: Biological process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular function (MF), while KEGG mainly focuses on cell signaling pathways. Figures 6 and 7 shows some functional annotations with the most significant differences in GO and KEGG of mRNA, LncRNA, and miRNA respectively. Due to the large number of enriched terms in the three functions of BP, CC, and MF, it was impossible to show all the enrichment analysis results. Therefore, the terms of BP, CC, and MF were sorted from largest to smallest according to the number of differentially expressed genes (S gene number), and Top25, Top15, and Top10 terms were selected respectively for drawing display. The GO function of differential genes is mainly concentrated in innate immune response, G protein-coupled receptor activity, transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling pathway, and mannosyl glycoprotein 4-β-n-acetylglucosamine transferase activity, intracellular calcium homeostasis, negative regulation of interleukin-12 production, B-cell receptor signaling pathway, extracellular ligand-gated monatomic ion channel activity, positive regulation of B-cell proliferation, protein binding, protein kinase activity regulation, Golgi function, endoplasmic reticulum function, ATP activity, enzyme binding and other biological processes (Fig. 6A–C). KEGG analysis showed that the regulation of hypoxia on yak Sertoli cells was mainly concentrated in retinol metabolism, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, primary immune deficiency, steroid hormone biosynthesis, NF-κB signaling pathway, natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, arachidonic acid metabolism, calcium signaling pathway, linoleic acid metabolism, Ras signaling pathway, nucleotide excision repair, inflammatory mediators regulation of TRP channels and Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation, MAPK signaling pathway, RAS signaling pathway, FoxO signaling pathway, Th17 cell differentiation, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, mitochondrial autophagy, tight junction, endocytosis and other signaling pathways (Fig. 7A–C).

Interaction network of DEmRNAs-DELncRNAs-DEmiRNAs

This part of the Cytoscape interaction network has a lot of results, so we will not show all of them here. We selected 5 genes closely related to the function of Sertoli cells and analyzed their ceRNA interaction network. These molecules were as follows: SLC2A1 (GLUT1), CLDN1, CRB2, STAR, CPXM1. The establishment of the ceRNA interaction network showed that ncRNA plays an important role in the hypoxic response of yak Sertoli cells, maintaining the balance under hypoxia, and assisting spermatogenesis by regulating biological processes such as cellular glucose metabolism, mitochondrial homeostasis, cell polarity, tight junction, and hormone synthesis. There were 4 target miRNAs and 114 LncRNAs of SLC2A1 (GLUT1). There were 2 target miRNAs and 136 LncRNAs of CLDN1. There were 2 target miRNAs and 212 LncRNAs of CRB2. There were 1 target miRNA and 30 LncRNAs for STAR. There were 1 target miRNA and 99 LncRNAs of CPXM1 (Fig. 8).

Discussion

The nutrition and energy provided by Sertoli cells are the prerequisites for testicular development and spermatogenesis in animals. In this study, the effects of hypoxia (5% O2) on the gene expression and function of yak Sertoli cells and the role of ncRNAs were analyzed by whole transcriptomics, to further explore the possible special regulatory mechanism of yak testicular response to hypoxia. We first constructed linear RNA libraries and miRNA libraries, respectively, to measure the expression of mRNAs, LncRNAs, and miRNAs in yak Sertoli cells before and after hypoxia treatment. After sequencing and comparative analysis, a total of 40,826 mRNAs, 26,891 LncRNAs, and 92,741 miRNAs were obtained, indicating that ncRNAs may be involved in the regulation of hypoxia on Sertoli cell function.

Compared with the normoxia group, there were 194 DEmRNAs in the hypoxia group, of which 134 mRNAs were up-regulated and 55 mRNAs were down-regulated. The GO function of differential genes was mainly concentrated in innate immune response, G protein-coupled receptor activity, transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling pathway, and mannosyl glycoprotein 4-β-n -acetylglucosamine transferase activity, calcium-mediated signaling regulation, intracellular calcium homeostasis, negative regulation of interleukin-12 production, B-cell receptor signaling pathway, extracellular ligand-gated monatomic ion channel activity, positive regulation of B-cell proliferation and other biological processes. These results indicate that hypoxia changed the microbiogenic environment by regulating immune molecular activation, glucose metabolism, signal transduction, and calcium ion transport in yak Sertoli cells. KEGG analysis showed that the regulation of hypoxia on yak Sertoli cells was mainly concentrated in retinol metabolism, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, primary immune deficiency, steroid hormone biosynthesis, NF—κB signaling pathway, natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, arachidonic acid metabolism, calcium signaling pathway, linoleic acid metabolism, Ras signaling pathway, nucleotide excision repair, inflammatory mediators regulation of TRP channels, and Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation signaling pathways. It was concluded that hypoxia had significant effects on the metabolism and immune function of yak Sertoli cells. The expression levels of glucose metabolizing genes HK2, MCT4, and GLUT3 were significantly increased, suggesting that hypoxia improved the energy conversion and supply of Sertoli cells and was conducive to spermatogenesis in yaks31,32,33. Studies have shown that Sertoli cells can selectively express some immunomodulatory factors to maintain immune regulation, including TGF-β, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. This is conducive to the survival of germ cell34. And literature has shown that in the process of spermatogenesis, the residue of spermatogenic cell death can be engulfed by Sertoli cells, and harmful substances invading spermatogenic epithelium and invading bacteria and viruses were also cleared by Sertoli cells35,36,37, so the activation of Sertoli cell immune function effectively guarantees the spermatogenic environment of the testis. Vascular epidermal growth factor (VEGFA) and connective tissue growth factor CCN5 were increased at the same time, indicating that hypoxia promoted the growth of Sertoli cells and inhibited testicular fibrosis38,39.

There were 934 DELncRNAs between the yak Sertoli cells in the hypoxia group and normoxia group, among which 497 LncRNAs were up-regulated and 437 LncRNAs were down-regulated. It was found that LncRNA Tug1 maintains the integrity of the blood-testicular barrier by regulating the expression of CCl240, and LncRNA MEG3 inhibits the proliferation and apoptosis of testicular spermatogenic cells41. LncWNT3-IT affects the proliferation of Sertoli cells by regulating the expression of WNT3 in goat testis42. The importance of LncRNA in the regulation of testicular function was demonstrated. We found that after hypoxia treatment of yak Sertoli cells, the GO function of differential LncRNAs was mainly concentrated in immune system development, cell development, and growth, regulation of translation accuracy, and JAK-STAT cascade signaling pathway. KEGG pathway analysis showed that the regulation of hypoxia on yak Sertoli cells was mainly concentrated in fructose and mannose metabolism, cell adhesion, and immune function regulation. Participating in these controls were ENSBGRT00000000971, ENSBGRT00000032566, ENSBGRT00000020112, ENSBGRT00000048815, ENSBGRT00000048815, ENSBGRT00000030575, ENSBGRT00000014254, ENSBGRT00000032649, ENSBGRT00000022812 and other DELncRNAs. Glucose metabolism is a pivotal regulatory factor in spermatogenesis, as evidenced by various studies. In male diabetic patients, disruptions in glucose metabolism can result in DNA damage to sperm, highlighting the critical role of glucose homeostasis in male fertility43. Melatonin has been found to enhance the survival of porcine Sertoli cells under heat stress conditions, potentially through its regulatory effects on glycolysis44. In the adult mouse testis, the hormone Asprosin has been shown to stimulate both steroid production and spermatogenesis by optimizing glucose metabolism45. Furthermore, the glucose-sensitive transcription factor MLX, which is involved in balancing metabolism and stress, has been identified as an inhibitor of apoptosis and a promoter of spermatogenesis46. These studies highlight the complex relationship between glucose metabolism and the maintenance of sperm health.

We found that hypoxia also had a regulatory effect on miRNA in yak Sertoli cells. There were 129 DEmiRNAs in the hypoxia group compared with normoxia group cells. The GO function of differential miRNA was mainly concentrated in the biological processes of protein binding, regulation of protein kinase activity, Golgi apparatus function, endoplasmic reticulum function, ATP activity, enzyme binding, etc., indicating that hypoxia has regulatory effects on gene transcription and translation and energy metabolism of yak Sertoli cells. KEGG analysis showed that the signaling pathways were mainly enriched in the MAPK signaling pathway, RAS signaling pathway, FoxO signaling pathway, Th17 cell differentiation, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, mitochondrial autophagy, tight junction, entosis, and other pathways, indicating that hypoxia had significant effects on energy metabolism and immune function of yak Sertoli cells. We found that bta-miR-2290 may have a targeting relationship with TGFB2, FLT4, IKBKB, MAPK8IP1, MAPK8, MAP3K20, and MAPKAPK3, and affect the MAPK pathway through regulation of these genes. The MAPK pathway plays an important role in testicular development, spermatogenesis, and maturation47,48,49. Bta-miR-11984, bta-miR-2308, bta-miR-2397-3p, bta-miR-503-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, bta-mir-502b-p5, and other miRNAs target multiple genes in the PI3K-AKT pathway50,51. It may be related to the regulation of proliferation, apoptosis, and autophagy of yak Sertoli cells under hypoxia. Targeting CCL19, TRAF5, IL1R1, and other genes, bta-miR-2308 can regulate the immune function of Sertoli cells in a hypoxic environment through the NF-κB signaling pathway52. Hypoxia enhanced the glucose metabolism of yak Sertoli cells and changed the energy supply. In this highly dynamic process, the enhancement of cellular immune function may contribute to the maintenance of cell homeostasis and enable yak Sertoli cells to adapt to hypoxia.

We then constructed the interaction between hypoxia with energy metabolism and tight junction genes of yak Sertoli cells. Claudin1 (CLDN1) is an important regulatory protein of the testis blood-testis barrier42. The combination of Claudin proteins determined the permeability of the tight junction and provided suitable conditions for spermatogenesis. We found that there was a targeting relationship between hsa-miR-320b, hsa-miR-539-3p, and CLDN1, and hypoxia significantly reduced the expression of hsa-miR-320b and hsa-miR-539-3p. miRNA exerts biological functions by participating in the regulation of the translation process of its downstream target genes. Studies have shown that hsa-miR-320b has a regulatory effect on the proliferation of breast cancer cells and prostate cancer cells53,54, while hsa-miR-539-3p is related to the damage protection of cardiomyocytes glucose deficiency, MDA content, LDH release, SOD activity and apoptosis under hypoxia55. The results of this study suggested that hsa-miR-320b and hsa-miR-539-3p may be involved in the regulation of hypoxia on CLDN1 of yak Sertoli cells, and then affect the tight connection of yak Sertoli cells and the formation of blood-testis barrier. There were 2 miRNAs that target CRB2, and 212 LncRNAs that the change of Sertoli cells polarity can help spermatogenic cells develop and differentiate, and promote spermatogenesis under a hypoxic environment56,57. GLUTs are a kind of important sugar transporter58. Bta-miR-2285 had a targeting relationship with GLUT1. Hypoxia may regulate the expression of GLUT1 through bta-miR-2285 and affect glucose metabolism in cells under hypoxia. In addition, we found that there is a targeting relationship between miR-188-5p and GLUT3. Studies have shown that miR-188-5p has a regulatory effect on the proliferation and invasion of various cancer cells, but its role in reproduction has not been studied58,59,60,61. These results suggested that miR-188-5p may regulate glucose metabolism in yak Sertoli cells in response to hypoxia, acting as a hub between hypoxia and glucose metabolism.

In conclusion, this study identified a total of 194 DEmRNAs, 934 DELncRNAs, and 129 DEmiRNAs in yak Sertoli cells under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. An interaction network among these differential genes was constructed, revealing that hypoxia significantly impacts the glucose metabolism, blood-testis barrier regulation, immune regulation, and other functions of yak Sertoli cells. These findings will provide valuable insights into the hypoxia response mechanism of yak testis, potentially advancing the field of plateau reproductive medicine.

Materials and methods

Culture and identification of primary yak Sertoli cells

Five pairs of adolescent yak testicles were collected from Tianzhu, Gansu Province, China, placed in sterile saline at 35–37 °C, and brought back to the laboratory within 4 h. In vitro isolation, culture and identification of yak Sertoli cells refer to the operation methods of Zomer et al.62 and Zhang et al.63. The cells were separated by the combined digestion method of collagenase and trypsin enzyme, hypotonic treatment with 20 mmol L−1 Tris–Hcl, and then purified by starvation treatment. The cells were then cultured in DMEM F12 medium containing 10% FBS under the conditions of 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 21% O2. After cell growth was stable, Feulgen staining and immunofluorescence staining of Fas Ligand (FASL) and GATA binding protein 4 (GATA4) proteins were used for identification.

Establishment of hypoxia model of yak Sertoli cells in vitro and total RNA quality detection

The normoxia culture condition for cells were 21% O2, 5% CO2, 74% N2, and the hypoxia culture conditions were 5% O2, 5% CO2, 90% N2. Yak Sertoli cells were collected and cultured under Normoxia (21% O2) and Hypoxia (5% O2) conditions for 48 h. And 6 biological replicates were set up in each group. Then 3 samples were randomly selected in each group and total RNA were extracted using TRIzol kit (TransGen, Beijing, China). RNA quality was assessed using Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer and and gel electrophoresis.

Library construction and whole transcriptome sequencing

Second strand cDNA was synthesized by DNA polymerase I, RNaseH, dNTPs (dUTP instead of dTTP), and buffer solution. The miRNA sequencing library was prepared using the TruSeq Small RNA Sample Prep Kits from Illumina, San Diego, USA. After the miRNA library preparation was completed, the constructed library was sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform, with a read length of 1 × 50 base pairs (single-end). For mRNA and lncRNA, a method of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion was used to construct strand-specific libraries. Once the library passed quality control, it was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq™ 6000 platform, with a read length of 2 × 150 base pairs (paired-end).

Data quality control and mapping to the reference genome

Illumina HiSeq2500 and Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencers were used to obtain raw data. Since raw data contained sequencing connector sequences, low-quality read segments, sequences with high N (N indicates uncertain base information) rate, and sequences with excessively short length, subsequent analysis results and quality were affected. Therefore, raw data needs to be preprocessed, and cutadpter was used to filter out unqualified sequences to obtain clean data, and then the next analysis was carried out. The specific processing steps were as follows: (1) reads with Adaptor were removed. (2) The proportion of reads containing N(N indicates that base information cannot be determined) was greater than 5%. (3) Low-quality Reads were removed (base number of reads with mass value Q ≤ 10 accounted for more than 20% of the whole read). (4) The original sequencing quantity, effective sequencing quantity, Q20, Q30, and GC contents were counted and comprehensively evaluated. Then, hisat was used to compare the reference genomes of the pre-processed Valid Data, and the gene location information specified in the genome annotation file gtf was counted respectively, including (1) the sequencing data was compared with the reference genome Reads statistics. (2) Chromosome density distribution of sequencing data compared with the reference genome. Then the sequence of Clean Reads was compared with the yak reference genome sequence (http://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-104/fasta/bos_grunniens/dna/) to obtain mapped reads for expression calculation and subsequent transcript assembly.

Identification and analysis of miRNA, lncRNA and mRNA

The original sequencing data was first removed with the 3 'splitter sequence, removing sequences with sequence base lengths less than 18nt, filtered out if the sequence contains 80% A or C or G or T, 3N (not necessarily continuous), only A, C without G, T, or only G, T without A, C, or continuous nucleotide dimers and trimers. At the same time, the measured sequences were compared and filtered with mRNA, RFam (including rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, snoRNA) and Repbase database, and the filtered data were further compared, identified and predicted for miRNA. After the Reads were assembled using StringTie, known mRNA and transcripts smaller than 200 bp were removed, and lncRNA predictions were performed on the remaining transcripts. The prediction software was CPC (Coding Potential Calculator) and CNCI (Coding-non-coding Index). If these remaining transcripts have the potential to encode a protein, we classified them as novel mRNA, then defined them as mRNAs and filter them. Finally, the lncRNA sequence was obtained through some filtering conditions. Differentially expressed miRNAs, LncRNAs and mRNAs were screened with fold change ≥ 2 (|log2FC|≥ 1) and p < 0.05 as the threshold.

Validation of sequencing results by RT-qPCR

To confirm the accuracy of the data obtained from RNA-Seq, 12 mRNAs (MCT4, BNIP3, VEGFA, STC2, HK2, TSPYL5, ZNF395, PTGES, LONRF1, RAB5A, SLCO2A1 and CCN5), 6 LncRNAs (ENSBGRT00000031412, ENSBGRT00000034936, ENSBGRT00000007294, ENSBGRT00000000971, MSTRG.30475.1, and ENSBGRT00000007977), and 10 miRNAs (bta-miR-1260, hsa-miR-433-3p, bta-miR-7859, bta-miR-345-5p, hsa-miR-7977, mmu-miR-193a, bta-miR-2478, hsa-miR-210-3p, bta-miR-2483-5p, and bta-miR-6120-3p) were randomly selected, and their expression levels were verified by q-PCR. The Evo M-MLV RT Kit with gDNA Clean for qPCR II was used to reverse transcribe the linear RNA in the total RNA. Mir-X miRNA First-Strand Synthesis Kit was used to reverse transcribed miRNAs in total RNA. The q-PCR assay was performed using TB Green®Premix Ex Taq™. mRNAs and LncRNAs were amplified by a three-step process as follows: 95 °C, 5 min (pre-denaturation), 95 °C, 30 s (denaturation), 52–60 °C, 20 s (annealing), 72 °C, 30 s (extension), 40 cycles. miRNAs were amplified using a two-step process with the following procedures: 5 min at 95 °C (pre-denaturation), 30 s at 95 °C (denaturation), 15 s at 60 °C (annealing), and 40 cycles.

Primer sequence and annealing temperature are shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5. β-actin and U6 are the internal reference genes of linear RNAs and miRNAs, respectively. All primers in this study were designed based on the sequence obtained by sequencing. Downstream primers of miRNA are general primers included in the reverse transcription kit and are not shown in the table. The 2 −∆∆Ct method was used to calculate the relative expression levels of the two cell detection genes obtained by q-PCR, and statistical analysis was performed using IBM spss statistics 25.0 software, and the FPKM value in the sequencing result was converted into log2FC for comparison with the q-PCR result. The reliability of sequencing data was determined by the differential expression ratio between RNA-seq and q-PCR.

GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis

To better understand the biological functions and potential mechanisms of ncRNAs and mRNAs in yak Sertoli cells in response to hypoxia, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis were performed for differentially expressed mRNAs (DEmRNAs), LncRNAs (DELncRNAs) and miRNAs (DEmiRNAs)64,65. The cis-target genes and trans-target genes of LncRNAs were predicted according to the position relationship and expression level correlation between LncRNAs and mRNAs. Genes in the upstream and downstream 100 Kb range of LncRNAs were considered to be cis-target genes. The Pearson correlation coefficient method was used to analyze the correlation between LncRNA and mRNA among samples, and the correlation between them was greater than 0.9, and the P < 0.01 is considered to have a trans-targeting relationship. Target genes of miRNAs were predicted using miRanda and Targetscan software. According to the Wallenius noncentral hypergeometric distribution principle, the differential genes and their target genes were enriched by GOseq R packages, and the KEGG pathway was analyzed by KOBAS 2.0 software.

Interaction network of DEmRNAs-DELncRNAs-DEmiRNAs

Due to the large number of different LncRNAs, we used fold change ≥ 2 (|log2FC|≥ 1), p < 0.05, q < 0.05 as thresholds to screen LncRNA differential expression in order to more accurately analyze the RNA interaction relationship. Based on the prediction results of LncRNAs and miRNAs target genes, this study uses Cytoscape software to construct the network relationships between DEmRNAs, DELncRNAs, and DEmiRNAs. A total of 68,662 DEmRNAs-DELncRNAs-DEmiRNAs relationship pairs were constructed, which were not visually analyzed due to their large number. In addition, the interaction between LncRNA, miRNA and the genes of glucose metabolizer GLUT1 and tight junction molecule CLDN1 and other genes, was constructed respectively.

Ethics statement

All experiments in this study have been approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Gansu Agricultural University (Ethic approval file No. GSAU-Eth-VMC-2023-004), and all operations are carried out in strict accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the [Sequence Read Archive, SAR] repository. The primary accession code is PRJNA1083316. The BioSample accessions are SAMN40244622, SAMN40244623, SAMN40244624, SAMN40244625, SAMN40244626, SAMN40244627. [https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1083316?reviewer=le5551787tmumq8bdc850mtfkv].

References

JankovicVelickovic, L. & Stefanovic, V. Hypoxia and spermatogenesis. Int Urol Nephrol 46(5), 887–894 (2014).

Liao, W. et al. Hypobaric hypoxia causes deleterious effects on spermatogenesis in rats. Reproduction 139(6), 1031–1038 (2010).

Raisi, A. & Davoodi, F. Testicular torsions in veterinary medicine. Vet. Res. Commun. 46(2), 303–313 (2022).

Oyedokun, P. A. et al. Impact of hypoxia on male reproductive functions. Mol. Cell Biochem. 478(4), 875–885 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Effects of environmental and pathological hypoxia on male fertility. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 725933 (2021).

Li, S. & Yang, Q. E. Hypobaric hypoxia exposure alters transcriptome in mouse testis and impairs spermatogenesis in offspring. Gene 823, 146390 (2022).

He, T. et al. Hypoxia-induced alteration of RNA modifications in the mouse testis and spermdagger. Biol. Reprod. 105(5), 1171–1178 (2021).

Meroni, S. B. et al. Molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways involved in sertoli cell proliferation. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 10, 224 (2019).

Bai, G., et al. Hypobaric hypoxia causes impairment of spermatogenesis in developing rats at pre-puberty. Andrologia (2018).

Yao, C. et al. Protection of pentoxifylline against testis injury induced by intermittent hypobaric hypoxia. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 3406802 (2016).

Wei, H. et al. Melatonin through blockade of Hif-1alpha signaling mediates the anti-fibrosis under hypoxia in canine Sertoli cells. Reprod. Biol. 22(4), 100677 (2022).

Ma, C. et al. miR-762 promotes porcine immature Sertoli cell growth via the ring finger protein 4 (RNF4) gene. Sci. Rep. 6, 32783 (2016).

An, X. et al. miR-1285-3p targets TPI1 to regulate the glycolysis metabolism signaling pathway of Tibetan sheep Sertoli cells. PLoS One 17(9), e0270364 (2022).

Zhuo, L. et al. The role of miR-199a-3p in inhibiting the proliferation of spermatogonial stem cells under heat stress. Theriogenology 211, 56–64 (2023).

Gan, M., et al. Potential function of testicular MicroRNAs in heat-stress-induced spermatogenesis disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(10) (2023).

Wang, S., et al. RNA-seq analysis of testes from mice exposed to neodymium oxide. Toxics 11(12) (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. MicroRNA-30a-5p regulates cypermethrin-induced apoptosis of Sertoli cells by targeting KLF9 in vitro. Reprod. Toxicol. 119, 108414 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Sertoli cells-derived exosomal miR-30a-5p regulates ubiquitin E3 ligase Zeb2 to affect the spermatogonial stem cells proliferation and differentiation. Reprod. Toxicol. 117, 108340 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Regulatory effects of HIF-1alpha and HO-1 in hypoxia-induced proliferation of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells in yak. Cell Signal 87, 110140 (2021).

Ruan, C. M. et al. Proteomic analysis of Tianzhu White Yak (Bos grunniens) testis at different sexual developmental stages. Anim. Sci. J. 90(3), 333–343 (2019).

Cao, M., et al., Analysis of chromatin openness in testicle tissue of yak and cattle-Yak. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(24) (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Transcriptome sequencing reveals differences between leydig cells and sertoli cells of yak. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 960250 (2022).

Huang, Q. et al. Changes in volatile flavor of yak meat during oxidation based on multi-omics. Food Chem. 371, 131103 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Transcriptomic study of yak mammary gland tissue during lactation. Anim. Biotechnol. 33(4), 672–679 (2022).

Zhao, H. et al. Transcriptomics and metabolomics of blood, urine and ovarian follicular fluid of yak at induced estrus stage. BMC Genomics 25(1), 201 (2024).

Long, K. et al. Small non-coding RNA transcriptome of four high-altitude vertebrates and their low-altitude relatives. Sci Data 6(1), 192 (2019).

Wang, K. et al. Different gene expressions between cattle and yak provide insights into high-altitude adaptation. Anim. Genet. 47(1), 28–35 (2016).

Robert, N. et al. Expression of Rad51 and the histo-morphological evaluation of testis of the sterile male cattle-yak. Theriogenology 172, 239–254 (2021).

Zou, S. et al. Heat shock protein 60 expression and localisation in different tissues and testis development of male cattle (cattle-yak and yak). Folia Morphol. (Warsz) 80(4), 857–869 (2021).

Liu, P. et al. Regulation by Hsp27/P53 in testis development and sperm apoptosis of male cattle (cattle-yak and yak). J. Cell Physiol. 234(1), 650–660 (2018).

Galardo, M. N. et al. Participation of HIFs in the regulation of Sertoli cell lactate production. Biochimie 132, 9–18 (2017).

Zhang, X.N., et al., Ldha-dependent metabolic programs in sertoli cells regulate spermiogenesis in mouse testis. Biology (Basel). 11(12) (2022).

Yang, C. X. et al. HSP90AA1 promotes viability and lactate production but inhibits hormone secretion of porcine immature Sertoli cells. Theriogenology 194, 64–74 (2022).

Washburn, R. L. et al. Sertoli cell immune regulation: A double-edged sword. Front. Immunol. 13, 913502 (2022).

O’Donnell, L., Smith, L. B. & Rebourcet, D. Sertoli cells as key drivers of testis function. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 121, 2–9 (2022).

Washburn, R. L., Kaur, G., & Dufour, J. M. Mouse sertoli cells inhibit humoral-based immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(21) (2022).

Fang, Y. et al. Varicocele-mediated male infertility: From the perspective of testicular immunity and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 12, 729539 (2021).

Ahmadi, H. et al. Sertoli cells avert neuroinflammation-induced cell death and improve motor function and striatal atrophy in rat model of huntington disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 65(1), 17–27 (2018).

Barkin, J. M. et al. Significance of CCNs in liver regeneration. J. Cell Commun. Signal 17(2), 321–332 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. LncRNA Tug1 maintains blood-testis barrier integrity by modulating Ccl2 expression in high-fat diet mice. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 79(2), 114 (2022).

Zhou, X. et al. Silencing of MEG3 attenuated the role of lipopolysaccharides by modulating the miR-93-5p/PTEN pathway in Leydig cells. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 19(1), 33 (2021).

He, L. et al. LncWNT3-IT affects the proliferation of Sertoli cells by regulating the expression of the WNT3 gene in goat testis. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 55(9), 1061–1071 (2020).

Dias, T. R. et al. Sperm glucose transport and metabolism in diabetic individuals. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 396(1–2), 37–45 (2014).

Deng, C. C. et al. Melatonin alleviates the heat stress-induced impairment of Sertoli cells by reprogramming glucose metabolism. J. Pineal. Res. 73(3), e12819 (2022).

Maurya, S. et al. Asprosin promotes steroidogenesis and spermatogenesis with improved glucose metabolism in adult mice testis. Andrologia 54(11), e14579 (2022).

Carroll, P. A., et al. The glucose-sensing transcription factor MLX balances metabolism and stress to suppress apoptosis and maintain spermatogenesis. Plos Biol. 19(10) (2021).

Ma, Q. et al. Changes in the tight junctions of the testis during aging: Role of the p38 MAPK/MMP9 pathway and autophagy in Sertoli cells. Exp. Gerontol 161, 111729 (2022).

Luo, D. et al. Role of p38 MAPK signalling in testis development and male fertility. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 6891897 (2022).

Yang, F. et al. FGF9 promotes mouse spermatogonial stem cell proliferation mediated by p38 MAPK signalling. Cell Prolif 54(1), e12933 (2021).

Deng, C. Y. et al. The role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway in male reproduction. Curr. Mol. Med. 21(7), 539–548 (2021).

Chen, K. Q. et al. The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway: How does it regulate development of Sertoli cells and spermatogenic cells?. Histol. Histopathol. 37(7), 621–636 (2022).

Zhang, M. F. et al. Transcription factor Dmrt1 triggers the SPRY1-NF-kappaB pathway to maintain testicular immune homeostasis and male fertility. Zool Res. 44(3), 505–521 (2023).

Jingyang, Z. et al. Mir-320b inhibits pancreatic cancer cell proliferation by targeting FOXM1. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 22(8), 1106–1113 (2021).

Li, J. et al. LINC00680 modulates docetaxel resistance in breast cancer via the miR-320b/CDKL5 axis. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 36, 3946320221105608 (2022).

Tang, Y. et al. AK003290 protects myocardial cells against apoptosis and promotes cardiac function recovery via mir-539-3p/erbb4 axis in ischemic-reperfusion injury. DNA Cell. Biol. 40(12), 1528–1538 (2021).

Moller-Kerutt, A., et al., Loss of surface transport is a main cellular pathomechanism of CRB2 variants causing podocytopathies. Life Sci. Alliance 6(3) (2023).

Paniagua, A. E. et al. CRB2 completes a fully expressed crumbs complex in the retinal pigment epithelium. Sci. Rep. 5, 14504 (2015).

Holman, G. D. Structure, function and regulation of mammalian glucose transporters of the SLC2 family. Pflugers Arch. 472(9), 1155–1175 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. MiR-188-5p inhibits cell proliferation and migration in ovarian cancer via competing for CCND2 with ELAVL1. Cell Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand) 69(3), 69–74 (2023).

Wang, H., et al. Hsa_circ_0001741 suppresses ovarian cancer cell proliferations through adsorption of miR-188-5p and promotion of FOXN2 expression. Mol. Biotechnol. (2023).

Yin, Z. et al. miR-188-5p and host MALAT1 regulate RBE cell migration, invasion, and apoptosis via up-regulating PSMD10 in cholangiocarcinoma. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 195(1), 655–671 (2023).

Zomer, H. D. & Reddi, P. P. Characterization of rodent Sertoli cell primary cultures. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 87(8), 857–870 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Pure cultures and characterization of yak Sertoli cells. Tissue Cell 45(6), 414–420 (2013).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1), D587–D592 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the College of Veterinary Medicine of Gansu Agricultural University for providing the experimental platform and the Livestock Embryo Engineering Research Center of Gansu Province for their help in collecting yak testis.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32372974) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32273091).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data curation: R.M. Formal analysis: J.H., Funding acquisition: Y.C., S.Y., Investigation: R.M., X.B., S.Y., Methodology: R.M., Y.W., L.Z., Supervision: J.H., Y.P., Y.C., S.Y., Writing—original draft: R.M., Writing—review & editing: Y.P., Y.C., S.Y. R.M. wrote the main manuscript text and Y.P., Y.C., and S.Y. reviewed the manuscript. X.B., S.Y. prepared Figs. 1–4. Y.W., L.Z. prepared Figs. 5–8. J.H. prepared the formal analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, R., Cui, Y., Yu, SJ. et al. Whole transcriptome sequencing revealed the gene regulatory network of hypoxic response in yak Sertoli cells. Sci Rep 14, 19903 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69458-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69458-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparative RNA-Seq analysis of differentially expressed genes in the sertoli cells of yak and cattle-yak

BMC Veterinary Research (2025)