Abstract

We present a methodology for the synthesis of inorganic-organic Janus-type molecules based on mono-T8 and difunctionalized double-decker silsesquioxanes (DDSQs) via hydrosilylation reactions, achieving exceptionally high yields and selectivities. The synthesized compounds were extensively characterized using various spectroscopic techniques, and their sizes and spatial arrangements were predicted through molecular modelling and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Quantum chemical calculations were employed to examine the interactions among four molecules of the synthesized compounds. These computational results allowed us to determine the propensity for molecular aggregation, identify the functional groups involved in these interactions, and understand the changes in interatomic distances during aggregation. Understanding the aggregation behaviour of silsesquioxane molecules is crucial for tailoring their properties for specific applications, such as nanocomposites, surface coatings, drug delivery systems, and catalysts. Through a combination of experimental and computational approaches, this study provides valuable insights into the design and optimization of silsesquioxane-based Janus-type molecules for enhanced performance across various fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxanes (SQs, POSS®)1 belong to a large and diverse class of specific organosilicon frameworks with inorganic Si-O-Si core and organic coronae, constituting hybrid molecules of the general formula (RSiO3/2)n up to n=18. They exhibit diverse architectures, from random via ladder to partially or closed caged ones2,3. Still, from the application point of view, the most important are cube-like T8 derivatives but also double-decker silsesquioxanes (DDSQ)4,5,6. SQs for their unique physicochemical properties have found application in many branches of chemistry, e.g. in materials (building blocks or polymer modifiers)7,8, optoelectronics (e.g. sensors, OLED devices)9, heterogeneous catalysis10, or in medicine (e.g. drug delivery systems)11,12.

Janus particles have been known in the literature for nearly twenty years. Nonetheless, they are still arousing scientific interest. These systems are characterized by exclusive properties due to their asymmetrical structure that constitutes two kinds of surfaces with diverse physico-chemical features. In 1989, Casagrande and Veyssie were the firsts to describe spherical glass particles with one of the hemisphere hydrophobic and another hydrophilic. In their report, the amphiphilic beads were synthesized by protecting one of the hemispheres with cellulose varnish and treating another part of the molecule with a silane reagent (octadecyl trichlorosilane)13. The unique surface of Janus molecule allows two distinct types of chemistry and physics to occur on the same particle14. Until now, in the scientific literature, Janus molecules have been based mainly on: polystyrene and poly (methyl methacrylate), polyacrylic acid, gold and iron oxides, fibers, allyl alcohol, protein cages, and pigments15,16,17. Thanks to the fact that they possess two distinct “faces” in their structure, it makes them a particular class of materials among microparticles16. Janus molecules can be divided into a few groups, according to their architecture and dimensionality e.g. spherical, two types of disc-like particles and two types of cylinders16. Due to such different physical and chemical properties in one structure, the synthesis of Janus particles has remained challenging for a long time. It requires the ability to create (selectively and with high yield) each hemisphere particle with individual features in a unique way. Currently, few major methods have been applied in the synthesis of these systems, e.g. masking, self-assembly, phase separation14. One of the most popular and important strategies for the Janus particles synthesis is to temporarily immobilize one face of a particle for symmetry-breaking. On the other hand, masking involves the protection of one side of a nanoparticle followed by the modification of the unprotected side and the removal of the protection14.

Since the last decade, Janus-type molecules have found numerous applications, among others as nanocorals18, water-repellent fibers15, catalyst, stabilizers in emulsions19, batteries20, nanocomposites, membranes, novel compatibilizer for PS/PMMA polymer blends21,22, and as an amphiphilic colloidal surfactants13,14. The use of spherical Janus molecules has allowed increasing work efficiency of optical probes for biological interactions or rheological measurements in confined space (compared to ordinary molecules). With this strategy, it is possible to create devices ranging from precise nanoviscosimeters to nanothermometers23,24,25.

The extension of the synthetic approach towards Janus particles has been also reflected in the use of specific organosilicon frameworks, i.e. functionalized silsesquioxanes (SQs). In recent years, Professor Unno research group has reported the formation of Janus-type inorganic-organic nanoparticles based on cubic T8 silsesquioxane containing four phenyl groups and four iso-butyl groups in the cage26. The other results refer to the synthesis of the same cubic structure with a different kind of inert groups affecting the physical properties of these molecules27,28,29. The synthesis of Janus-type nanoparticles based on silsesquioxanes involves the formation of organic-inorganic hybrids which properties become dual. The inorganic core of silsesquioxane provides, among others very good thermal and mechanical stability, dielectric properties, oxidation resistance as well as non-flammability. A properly selected organic inert group (alkyl and aryl type) can positively influence, e.g. solubility in organic solvents, amphiphilic or optoelectronic properties. By combining two silsesquioxane (SQ) compounds with different organic substituents into one molecule, one can enhance the functional versatility of the resulting system. This may enable modulation of its solubility in organic and/or aqueous solvents, potential self-assembly capabilities, and diversification of chemical reactivity.

Their further application is also possible, e.g. as complex metals and anions, used as a selective sensor for the recognition of ions and biomolecules30. Janus-type particles containing silsesquioxanes may form amphiphilic molecules to obtain improved colloidal surfactants or solvent separation membranes31,32,33. The use of silsesquioxanes for the synthesis of Janus molecules improves the compatibility properties in polymer mixing, reduces the size of domains and structural defects as well as enhances the mechanical properties of the entire system (e.g. in Young’s modulus and strain at the break or hardness)31,34. The scientific literature concerning synthetic methodology using silsesquioxanes for the formation of Janus-type nanoparticles is still limited and mainly based on mono- and octafunctionalized silsesquioxanes20,21, 30, 31, 34,35,36,37,38,39. Moreover, there are no literature reports on the use of DDSQs that are still quite novel class of organosilicon Si-O-Si frameworks.

The proposed research fulfills the idea of basic research as it concerns the original experimental work undertaken to acquire new information on the synthesis and finally the properties of Janus-type molecules containing silsesquioxanes with diverse organic coronae. The synthesis of Janus-type molecules utilizing silsesquioxanes and DDSQ-type system and selection of catalytic protocols to yield those systems, represents a significant advancement in this field of chemistry. By leveraging the structural versatility and reactivity of double-decker silsesquioxanes alongside the precise control afforded by hydrosilylation chemistry, this research paves the way for tailored Janus architectures with enhanced functionality and tunable properties. The scope of this study includes an application of hydrosilylation in presence of TM complexes, e.g. platinum, for the preparation of products (Fig. 1). Hydrosilylation has been a fundamental synthetic path leading to saturated or unsaturated organosilicon compounds40. It is a convenient synthetic tool of fundamental importance in the industry towards the formation of molecular and macromolecular organosilicon compounds of desirable physical and chemical properties41. In addition to experimental synthesis, this research integrates computational molecular modeling and Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to provide crucial insights into the structural properties and electronic behaviors of the designed Janus molecules. By combining experimental findings with computational modeling, a comprehensive understanding of the structure-function relationships and potential applications of the synthesized Janus molecules can be achieved. This synergistic approach not only validates experimental observations but also enables predictive modeling and facilitates further refinement of molecular design strategies, offering a holistic framework for advancing the field of Janus molecule synthesis and applications.

Experimental section

Materials

The chemicals were purchased from the following sources: Sigma-Aldrich for toluene, chloroform, dichloromethane-d, THF, chloroform-d, Karstedt’s catalyst ([Pt2(dvs)3]) (2% xylene solution), Chloro(1,5-cyclooctadiene)iridium(I) dimer ([Ir(cod)Cl]2) and silica gel 60. AmBeed for 2-Dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,4′,6′-triisopropylbiphenyl (XPhos). Thermo Scientific Acros for PtO2. Pt/SDB was prepared according to the previously reported method42. The following silsesquioxanes: DDSQ-2SiOSiVi and DDSQ-2SiVi and 1-dimethylsiloxy-3,5,7,9,11,13,15-hepta(ethyl)pentacyclo[9.5.1.13,9.15,15.17,13]octasiloxane (Et7T8H), 1-dimethylvinylsiloxy-3,5,7,9,11,13,15-hepta(phenyl)pentacyclo[9.5.1.13,9.15,15.17,13]octasiloxane (Ph7T8Vi), 1-dimethylsiloxy-3,5,7,9,11,13,15-hepta(isobutyl)pentacyclo[9.5.1.13,9.15,15.17,13]octasiloxane (iBu7T8H), 1-dimethylvinylsiloxy-3,5,7,9,11,13,15-hepta(isobutyl)pentacyclo[9.5.1.13,9.15,15.17,13]octasiloxane (iBu7T8Vi), 1-dimethylsiloxy-3,5,7,9,11,13,15-hepta(isooctyl)pentacyclo[9.5.1.13,9.15,15.17,13]octasiloxane (iOc7T8H), 1-dimethylsiloxy-3,5,7,9,11,13,15-hepta(phenyl)pentacyclo[9.5.1.13,9.15,15.17,13]octasiloxane (Ph7T8H) were prepared according to the literatures procedure43,44,45,46. All solvents were dried over CaH2 prior to use and stored under argon over 4Å molecular sieves. The liquid substrates were dried and degassed by bulb-to-bulb distillation. All syntheses were conducted under argon atmosphere using standard Schlenk-line and vacuum techniques.

Measurements

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

1H, 13C, and 29Si Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) were performed on Brucker Ultra Shield 400 and 300 spectrometers using CD2Cl2 or CDCl3 as a solvent. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm with reference to the residual solvent (CD2Cl2 or CDCl3) peaks for 1H and 13C and to TMS for 29Si NMR.

FT-IR spectroscopy

Fourier Transform-Infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded on a Nicolet iS5 (Thermo Scientific) spectrophotometer equipped with a diamond ATR unit. In all cases, 16 scans at a resolution of 2 cm−1 were collected, to record the spectra in a range of 4000-450 cm−1.

Elemental analyses

Elemental analyses were performed using a Vario EL III instrument.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

For both investigated compounds Ph7T8-T8Et7 and Ph7T8-T8iBu7 four molecules were used to create system for simulations. Our goal was to find possible interactions which will suggest aggregation of those structures. We also wanted to check how interatomic distances changes during simulation and if those distances affect the energy of the obtained clusters. The CHARMM36 force field was selected to perform Molecular Dynamics simulations as it is often used for this type of simulations47. Each molecule was parametrized with the use of PARATOOL48 program which is a plug-in for the molecular viewer VMD49. The molecular geometry of each compound was optimized at B3LYP/6-31+G(d)50,51 level of theory. Sets of point charges and a Cartesian Hessian matrices were obtained from natural population (NPA) and frequency analyses52 for each molecule studied. The calculations were performed with the Gaussian 09 programme53. Molecular Dynamics simulations were performed in chloroform box obtained with use of VMD Solvate Plugin54. Electrostatic and van der Waals interactions were treated with a cut-off of 12 Å as it was suggested for non-bonded interactions in simulations with CHARMM parameters55. The first step of each simulation was minimization. Energy minimization was followed by simulated annealing for 1.4 ns with temperature rising from 250 to 600 K56,57 and then decreasing back to 250 K. The last step of simulation was the production run during which temperature was kept at 298 K by applying to all heavy atoms the Langevin forces with damping coefficient of 1ps−158. Production run lasted 60 ns. All simulations were performed in NAMD 2.959. To assess the stability of the investigated systems we calculated RMSD (Root- mean-square deviation)60. Calculated RMSD were used to group conformers into eight clusters, with use of VMD Clustering plug-in, which is using quality threshold algorithm61,62. After completing simulations and grouping conformers to eight clusters, for each cluster average structures were obtained. Electronic energies of those structures were then computed with B3LYP63 method and 6-31++G(d,p)64 basis set which were also used for computational studies of similar compounds65,66,67. To take into account the effect of chloroform solvent we used the Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM)68.

Synthetic procedures

General synthetic procedure for Janus-type organic-inorganic molecules based on monofunctionalized silsesquioxanes obtained via hydrosilylation reaction

The procedure for the synthesis of Ph7T8-T8iBu7 is described as an example. Into a two-neck round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer Ph7T8Vi (0.047 g, 0.044 mmol), an anhydrous toluene (6 mL) and 1.0 equiv. of iBu7T8H (0.04 g, 0.044 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was heated up to 95 ℃ and 1×10−3 equiv. of [Pt2(dvs)3] (4.4×10−8 mol) was added. Reactions were carried out until >99% conversion of iBu7T8H, that was precisely controlled by FT-IR spectroscopy. After cooling it to room temperature, the excess of solvent was evaporated under vacuum and crude product was transferred onto chromatographic column (silica gel 60) using chloroform as an eluent. Evaporation of eluent gave an analytically pure sample of Ph7T8-T8iBu7 with 94% yield.

General synthetic procedure for Janus-type organic-inorganic molecules based on monofunctionalized silsesquioxane and difunctional DDSQ compounds obtained via hydrosilylation reaction

The procedure for the synthesis of DDSQ-2Si-(T8iBu7)2 is described as an example. Into a two-neck round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, DDSQ-2SiVi (0.034 g, 0.029 mmol), an anhydrous toluene (6 mL) and 2.0 equiv. of iBu7POSS-OSiMe2H (iBu7T8H) (0.05 g, 0.058 mmol) were added respectively. The reaction mixture was heated up to 95 ℃ and 2×10−3 equiv. of [Pt2(dvs)3] (5.8 ×10−8 mol) was added. Reactions were carried out until >99% conversion of iBu7T8H, that was precisely controlled by FT-IR spectroscopy, analysing the disappearance of signal at 2139 cm−1 (from Si-H bond). After cooling the reaction mixture to room temperature, the excess of solvent was evaporated under vacuum and crude product was transferred onto chromatographic column (silica gel 60) using chloroform as an eluent. Evaporation of eluent gave an analytically pure sample of DDSQ-2Si-(T8iBu7)2 with 93% yield.

Additional tests for hydrosilylation reaction of DDSQ-2SiVi with iOc7T8H in the presence of different catalysts

[IrCl(cod)]2 69

DDSQ-2SiVi (30 mg, 0.025 mmol), [IrCl(cod)]2 (0.7 mg, 2×10−6 mol) and anhydrous toluene (2 mL) were introduced into Schlenk reactor purged with argon and equipped with a magnetic stirrer. Afterwards iOc7T8H (64 mg, 0.05 mmol) in 3 mL of anhydrous toluene was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was heated up to 95 ℃ and carried out for 24 h. After cooling the reaction mixture to room temperature, the excess of solvent was evaporated under vacuum and crude product was transferred onto chromatographic column (silica gel 60) using chloroform as an eluent. Evaporation of eluent gave an analytically pure sample.

PtO2/XPhos70

PtO2 (0.02 mg, 6.5×10−7 mol) and XPhos (0.6 mg, 1.3×10−6 mol) and anhydrous THF (1 mL) were introduced into Schlenk reactor purged with argon and equipped with a magnetic stirrer. The reaction mixture was heated up to 60 ℃. Afterwards iOc7T8H (64 mg, 0.05 mmol) in 2 mL of THF and DDSQ-2SiVi (30 mg, 0.025 mmol) in 2 mL of THF were added dropwise. The reaction was carried out for 24 h. After cooling the reaction mixture to room temperature, the excess of solvent was evaporated under vacuum and crude product was transferred onto chromatographic column (silica gel 60) using chloroform as an eluent. Evaporation of eluent gave an analytically pure sample.

Pt/SDB42

DDSQ-2SiVi (30 mg, 0.025 mmol) and anhydrous toluene (2 mL) were introduced into Schlenk reactor purged with argon and equipped with a magnetic stirrer. Afterwards iOc7T8H (64 mg, 0.05 mmol) in 3 mL of anhydrous toluene was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was heated up to 90 ℃ and Pt/SDB was added (0.3 mg, 1.7×10−6 mol). Reaction was carried out for 24 h. After cooling the reaction mixture to room temperature, the excess of solvent was evaporated under vacuum and crude product was transferred onto chromatographic column (silica gel 60) using chloroform as an eluent. Evaporation of eluent gave an analytically pure sample.

Result and discussion

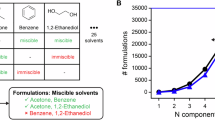

The reports on Janus-type compounds based on silsesquioxanes has been still limited. As a result, there was a scientific necessity to explore this area of chemistry. It should be underlined that the combinations of SQs structures with inert and functional groups anchored onto Si-O-Si core constitute a vast library of Janus-type organic-inorganic compounds of complex structural motifs that may possess various and interesting physical and chemical properties. This concept is an expansion of the up to date research in the area of SQ chemistry.

The first part of presented research was focused on hydrosilylation reaction of two monofunctionalized T8-type SQs possessing different inert groups anchored onto their cores (Ph, iBu, Et, iOc). Inert groups have been selected in great detail due to the differences in their physical and chemical properties (thermal stability, solubility, state of matter, modulus values, creep-recovery, reactivity, melting and crystallization temperatures, tensile strength and elongation) but also based on their availability44,71, 72. As pointed by Naka, physical properties (solubility, the state of matter, and their thermal behavior) are determined by, e.g. the type of chemically inert organic substituents present in the structure of SQ. It was observed that the thermal stability of the compounds increased with inert groups in a row: iBu < iOc < Ph44. Silsesquioxanes compounds with isobutyl groups yielded greater modulus values than their phenyl counterparts. Similar trends were observed with tensile strength and elongation at yield. Compounds with isobutyl groups also experienced less creep than their phenyl counterparts71. The main plot of the reaction along with the structures of exploited SQs structures is presented below (Fig. 2).

As an example, we present a Janus-type organic-inorganic molecule based on two monofunctionalized silsesquioxanes (containing two different types of groups: phenyl and iso-Butyl). Hydrosilylation reaction was performed using Karstedt’s catalyst, 10−3 mol per 1 mol of Si-H group were established basing on literature for molecular compounds. The reaction was monitored via FT-IR to detect complete conversion of iBu7T8H (Si-H bond disappearance at ῡ = 2138 and 900 cm−1). What is more, the process was strictly controlled by the 1H NMR with Si-H (4.71–4.69 ppm) as well as Si-HC=CH2 (6.14–5.68 ppm) chemical shifts disappearance from iBu7T8H and Ph7T8Vi respectively (Fig. 3). Also, the exclusive formation of the β-hydrosilylation product was confirmed, i.e. CH2 moiety presence was observed (0.53–0.50 ppm, Fig. 3) along with the absence of CH and CH3 groups, characteristics for α-hydrosilylation. The reaction product Ph7T8-T8iBu7 was isolated with 94% yield.

Formation of the desired product was also confirmed by 29Si NMR analysis. Nine signals, at 14.06, 12.33, −66.98, −67.76, −67.79, −78.16, −78.33, −108.81 and −109.46 ppm in the case of Ph7T8-T8iBu7 can be discerned (Fig. 4). The first two signals might be assigned to the SiM atoms shifted significantly in comparison to the respectively signals of SiM atoms of the substrates (14.06 and 12.33 ppm vs -2.97 and −1.43 ppm). Signals −66.98, −67.76 and −67.79 ppm are assigned to the SiT (from silsesquioxanes with iBu moieties), −78.16 and −78.33 are assigned to the SiT (from silsesquioxanes with Ph moieties), −108.81 is assigned to the SiQ (from silsesquioxanes with Ph moieties) and the last one −109.46 is assigned to the SiQ (from silsesquioxanes with iBu moieties). The integrated areas of these signals are in excellent agreement with the expected values.

All obtained products based on monofunctionalized silsesquioxanes are air-stable solids. They are soluble in organic solvents like DCM, CDCl3, THF and toluene but not in, e.g. methanol, MeCN. They were isolated an characterized by means of spectroscopic methods (NMR, FT-IR spectroscopy) and elemental analysis.

Structures of SQs may vary and even in the family of well-defined cages, so-called double-decker silsesquioxanes (DDSQ) are crucially different from T8-type systems. The structure of DDSQ includes two “decks” of cyclosiloxane rings stacked on top of one another with four phenyl groups at the silicon atoms of each ring (joined by oxygen bridges)4. Recent years have shown that the concept of synthesis of molecular and macromolecular organosilicon compounds based on DDSQ have led to two major trends in their development and our understanding of their interesting physicochemical properties. DDSQ might possess two or four reactive groups, therefore it is possible to obtain Janus-type molecular compounds differently silsesquioxanes. We focused our research on difunctional DDSQ and joined it with T8 SQs possessing different groups attached to their core (phenyl-Ph, iso-Butyl-iBu, Ethyl-Et, iso-Octyl-iOct) (Fig. 5). As a result a new type of Janus compounds based on silsesquioxanes differing in their Si-O-Si structures, resembling a dumbbell shape, were successfully obtained. To our knowledge this is the first example of DDSQs exploitation in formation of Janus-type compounds.

Reaction path for the hydrosilylation experiments of DDSQ-2SiVi with iBu7T8H (to yield product DDSQ-2Si-(T8iBu7)2) is described as an example. 2×10−3 mol of Karstedt’s catalyst per 1 mol of Si-H group was established based on literature reports. Estimated time for the reactions for all Janus-type organic-inorganic molecules was approximately 20–24 h. The reaction was monitored via FT-IR to detect complete conversion of iBu7T8H (Si-H bond disappearance at ῡ = 2138 and 900 cm-1). According to the state of the art, addition sequence and stoichiometry of reagents are important for proper course of the reaction, i.e. 2 equiv. of iBu7T8H per 1 equiv. of DDSQ-2SiVi. The reaction progress was also monitored by 1H NMR analyses. The disappearance of chemical shifts characteristic for Si-H (4.71–4.69 ppm) and Si-HC=CH2 groups (6.22–5.89 ppm) during hydrosilylation was observed (Fig. 6). What is more, the exclusive formation of the β-hydrosilylation product was confirmed, i.e. CH2 moiety presence (signal overlapped with signal from the CH2 of isobutyl group, i.e. 0.53–0.59 ppm) was observed along with the absence of CH and CH3 groups, characteristics for α-hydrosilylation. The reaction product DDSQ-2Si-(T8iBu7)2 was isolated with 93% yield.

Formation of the desired product was also confirmed by 29Si NMR analysis. Eight signals, at 12.20, −16.88, −66.99, −67.02, −67.81, −78.60, −79.60, and −109.50 ppm in the case of DDSQ-2Si-(T8iBu7)2 can be discerned (Fig. 7). The first signal might be assigned to the SiM (from SQ with iBu moieties), while the second is assigned to the SiD (from DDSQ), signals −66.99, −67.02 and −67.81 ppm are assigned to the SiT (from SQ with iBu moieties), while −78.60 and −79.60 ppm are assigned to the SiT (from DDSQ). The last one (−109.50 ppm) is assigned to the SiQ (from SQ with iBu moieties). The integrated areas of these signals are in excellent agreement with the expected values.

Obtained products are air-stable solids and can be synthesis on multigram scale with high yields. They are soluble in organic solvents like DCM, THF and toluene but not in, e.g. methanol, MeCN. They were isolated an characterized by means of spectroscopic methods and elemental analysis.

It is worth mentioning that hydrosilylation may not proceed with a complete selectivity control towards the desired product and side reactions may occur. There is one exception from the β-addition product exclusive formation during hydrosilylation reaction of DDSQ moieties with T8 derivatives, i.e. the reaction of DDSQ-2SiVi with iOc7T8H. Careful evaluation of 29Si NMR analysis of DDSQ-2Si-(T8iOc7)2 revealed multiplied signals for SiM and SiQ from iOc7T8 and also SiD from DDSQ-2Si (See supplementary materials, Fig. S27) which is characteristics for α-hydrosilylation product formation. This might be connected with the steric hindrance of bulky iOc groups. However, this was not observed for the hydrosilylation of iOc7T8H with DDSQ-2OSiVi. Therefore presence of α-hydrosilylation product in the case of DDSQ-2Si-(T8iOc7)2 might be related with other steric but also electron aspects of the reagent. Vinyl groups in DDSQ-2SiVi are connected directly to the DDSQ core while in DDSQ-2OSiVi they are separated by additional siloxane linkers (-OSiMe2-). This might explain the formation of only β-addition product in the case of DDSQ-2OSi-(T8iOc7)2. For that reason, additional tests of iOc7T8H hydrosilylation reaction with DDSQ-2SiVi with different catalysts known for their reactivity in that process, i.e. [IrCl(cod)]269, PtO2/XPhos70, Pt/SDB42 were performed (see ESI). Unfortunately none of them did ensure the complete conversion of Si-H bond.

Computational studies

Our simulations allowed us to find potential energy minima corresponding to the studied systems consisted of four molecules of Ph7T8-T8Et7 compound. Clustering analysis helped identify eight clusters based on simulation trajectory (coordinates of average structures of those systems are included in supplementary information Table S1–S8). Clusters numbering depend on how many structures from simulation trajectory fit to specific cluster (1 is for the biggest number of structures, 8 is for the lowest number of structures). These structures were used to obtain energies of the systems62.

The energetically favored cluster 2 (see Table 1) consisted of four molecules of Ph7T8-T8Et7; it is depicted in Fig. 8.

As it can be observed the aggregation of Ph7T8-T8Et7 molecules is so strong that it is hard to see four molecules separately. Figure 9 shows those four molecules coloured in red, grey, orange and black.

It can be observed that ‘red’ molecule of Ph7T8-T8Et7 is oriented with its ethyl groups to phenyl groups of black molecule. For orange and grey molecules it was observed that their ethyl groups are oriented to their phenyl groups. Ethyl groups of orange molecule and phenyl groups of grey molecule are also oriented to phenyl groups of red molecule.

Interatomic distances of each of obtained structures of Ph7T8-T8Et7 molecule were calculated on the basis of their coordinates. For cluster 2 with lowest energy four molecules of Ph7T8-T8Et7 had the interatomic distance respectively 22.72, 19.91, 19.79 and 20.46 Å. (See supplementary materials Table S4). The biggest interatomic distances for Ph7T8-T8Et7 molecule had cluster 5 (23.56 Å) and the lowest had cluster 8 (19.22 Å). From all of the obtained data it can be noticed that the lowest energy cluster is consisted of three Ph7T8-T8Et7 molecules with smaller interatomic distances (19.91, 19.79 and 20.46 Å) and one more extended conformation of the molecule (22.72 Å).

From all investigated systems (coordinates of average structures of those systems are included in supplementary information Table S5–S7) consisted of four molecules of Ph7T8-T8iBu7 the lowest energy had cluster 5 (see Table 2). Structure of cluster 5 system is depicted in Fig. 10.

In comparison to clusters observed for Ph7T8-T8Et7 in the case of Ph7T8-T8iBu7 clusters do not show interaction between four Ph7T8-T8iBu7 molecules. In all eight obtained clusters of Ph7T8-T8iBu7 the molecules interact with solvent molecules (chloroform) but not with one another - they are not close enough each other to say that they are aggregating.

From all structures of Ph7T8-T8iBu7 the largest interatomic distance was observed in cluster 3 (28.44Å). The smallest one in cluster 2 (23.21 Å). Cluster 5 with the lowest energy had structures with largest interatomic distances of 24.79, 28.07, 24.03 and 24.05 Å. Similarly as it was observed for Ph7T8-T8Et7 compound the energetically favoured cluster had three molecules of Ph7T8-T8iBu7 in the most compact conformation while the forth molecule was present in the extended conformation (See supplementary materials Table S8).

Conclusions

This study provides insights through experimental and computational methods on understanding silsesquioxane molecule aggregation for tailoring their future properties as nanocomposites, coatings, drug delivery systems, and catalysts.

In summary, we have developed an efficient and selective approach to synthesize Janus-type inorganic-organic molecules based on monofunctionalized silsesquioxanes (R7T8, where R = Et, Ph, iBu, iOc) and difunctional double-decker symmetric systems (DDSQ-2SiVi and DDSQ-2OSiVi). We revealed simple and effective methods for their synthesis and isolation, achieving high purity and thorough characterization. This work represents the first demonstration of the catalytic reactivity of monofunctionalized silsesquioxanes in hydrosilylation reactions with other monofunctional silsesquioxanes (leading to the formation of R7T8-T8R’7) and of di-substituted DDSQs with various monofunctional silsesquioxanes (resulting in DDSQ-2Si-(T8R7)2 and DDSQ-2OSi-(T8R7)2). All compounds were comprehensively investigated using NMR, FT-IR spectroscopy, and elemental analysis. Looking ahead, we anticipate developing new Janus compounds by modifying phenyl groups attached to the Si-O-Si core through halogenation and catalytic reactions such as Heck, Sonogashira, and Suzuki coupling. Computational investigations revealed the aggregation behavior of the synthesized molecules and enabled visualization of the most energetically preferred structures. Molecular modeling and DFT calculations provided detailed information on the interatomic distances within the compounds, depending on their interactions within studied clusters. This study offers valuable understanding through both experimental and computational methods, enhancing our comprehension of silsesquioxane molecule aggregation. These insights are crucial for tailoring their properties for future applications in nanocomposites, coatings, drug delivery systems, and catalysts.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

POSS - Hybrid Plastics. Regist. trademark.

Cordes, D. B., Lickiss, P. D. & Rataboul, F. Recent developments in the chemistry of cubic polyhedral. Chem. Rev. 110, 2081–2173 (2010).

Laird, M. et al. Large polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane cages: The isolation of functionalized POSS with an unprecedented Si18O27 core. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 3022–3027 (2021).

Dudziec, B. & Marciniec, B. Double-decker silsesquioxanes: Current chemistry and applications. Curr. Org. Chem. 21, 2794–2813 (2017).

Wang, M., Chi, H., Joshy, K. S. & Wang, F. Progress in the synthesis of bifunctionalized polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane. Polymers (Basel) 11, 2098–2118 (2019).

Li, L., Wang, H. & Zheng, S. Well-defined difunctional POSS macromers and related organic–inorganic polymers: Precision synthesis, structure and properties. J. Polym. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.20230428 (2023).

Ye, Q., Zhou, H. & Xu, J. Cubic polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane based functional materials: Synthesis, assembly, and applications. Chem. Asian J. 11, 1322–1337 (2016).

Zhou, H., Ye, Q. & Xu, J. Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane-based hybrid materials and their applications. Mater. Chem. Front. 1, 212–230 (2017).

Gon, M., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Recent progress on designable hybrids with stimuli-responsive optical properties originating from molecular assembly concerning polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane. Chem. Asian J. 17, e202200144 (2022).

Calabrese, C., Aprile, C., Gruttadauria, M. & Giacalone, F. POSS nanostructures in catalysis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 10, 7415–7447 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Multi-stimuli-responsive nanoparticles formed of POSS-PEG for the delivery of boronic acid-containing therapeutics. Biomacromolecules 24, 5071–5082 (2023).

Jafari, M. et al. Dendritic hybrid materials comprising polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) and hyperbranched polyglycerol for effective antifungal drug delivery and therapy in systemic candidiasis. Nanoscale 15, 16163–16177 (2023).

Poggi, E. & Gohy, J. F. Janus particles: From synthesis to application. Colloid Polym. Sci. 295, 2083–2108 (2017).

Walther, A. & Mu, A. H. E. Janus particles: Synthesis, self-assembly, physical properties, and applications. Chem. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr300089t (2013).

Synytska, A., Khanum, R., Ionov, L., Cherif, C. & Bellmann, C. Water-repellent textile via decorating fibers with amphiphilic Janus Particles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 3, 1216–1220 (2011).

Walther, A. & Müller, A. H. E. Janus particles. Soft Matter 4, 663–668 (2008).

Xu, L., Pradhan, S. & Chen, S. Adhesion force studies of Janus nanoparticles. Langmuir https://doi.org/10.1021/la700774g (2007).

Wu, L. Y., Ross, B. M., Hong, S. & Lee, L. P. Bioinspired nanocorals with decoupled cellular targeting and sensing functionality **. Small https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.200901604 (2010).

Valadares, L. F. et al. Catalytic nanomotors: Self-propelled sphere dimers. Small https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.200901976 (2010).

Chinnam, P. R. & Wunder, S. L. Polyoctahedral silsesquioxane-nanoparticle electrolytes for lithium batteries: POSS-lithium salts and POSS-PEGs. Chem. Mater. 23, 5111–5121 (2011).

Han, D., Zhang, Q., Chen, F. & Fu, Q. RSC advances using POSS—C 60 giant molecules as a novel compatibilizer for PS / PMMA polymer blends †. RSC Adv. 6, 18924–18928 (2016).

Han, D. et al. AC SC. Polymer (Guildf). 136, 84–91 (2018).

Anker, J. N., Behrend, C. J., Huang, H. & Kopelman, R. Magnetically-modulated optical nanoprobes (MagMOONs) and systems. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 293, 655–662 (2005).

Xu, H., Aylott, J. W., Kopelman, R., Miller, T. J. & Philbert, M. A. A real-time ratiometric method for the determination of molecular oxygen inside living cells using sol-gel-based spherical optical nanosensors with applications to rat C6 glioma. Anal. Chem. 73, 4124–4133 (2001).

Behrend, C. J. et al. Metal-capped Brownian and magnetically modulated optical nanoprobes (MOONs): Micromechanics in chemical and biological microenvironments †. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 10408–10414 (2004).

Tanaka, T., Hasegawa, Y., Kawamori, T., Kunthom, R. & Takeda, N. Synthesis of double-decker silsesquioxanes from substituted difluorosilane. Organometallics https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00896 (2018).

Asuncion, M. Z., Ronchi, M., Abu-Seir, H. & Laine, R. M. Synthesis, functionalization and properties of incompletely condensed ‘half cube’ silsesquioxanes as a potential route to nanoscale Janus particles. Comptes Rendus Chim. 13, 270–281 (2010).

Oguri, N., Egawa, Y., Takeda, N. & Unno, M. Janus-cube octasilsesquioxane: Facile synthesis and structure elucidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 9336–9339 (2016).

Shiba, H., Yoshikawa, M., Wada, H., Shimojima, A. & Kuroda, K. Synthesis of polycyclic and cage siloxanes by hydrolysis and intramolecular condensation of alkoxysilylated cyclosiloxanes. Chem. Eur. J. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201805942 (2019).

Blázquez-Moraleja, A., Pérez-Ojeda, M. E., Ramón Suárez, J., Jimeno, M. L. & Chiara, J. L. Chemical communications. Chem. Commun. 52, 5792–5795 (2016).

Chen, X. et al. Science of the total environment single step synthesis of Janus nano-composite membranes by atmospheric aerosol plasma polymerization for solvents separation. Sci. Total Environ. 645, 22–33 (2018).

Meng, Y., Li, W., Kunthom, R., Liu, H. Rational Design and Application of Superhydrophobic Fluorine-Free Coating Basedon Double-Decker Silsesquioxane for Oil-Water Separation. Polymer 304, 127143 (2024)

Li, W.; Liu, H. Rational Design and Facile Preparation of Hybrid Superhydrophobic Epoxy Coatings Modified byFluorinated Silsesquioxane-Based Giant Molecules via Photo-Initiated Thiol-Ene Click Reaction with Potential Applications.Chem. Eng. J. 480, 147943 (2024)

Laine, R. M. et al. Perfect and nearly perfect silsesquioxane (SQs) nanoconstruction sites and Janus SQs. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 46, 335–347 (2008).

Liu, H. et al. Unraveling the self-assembly of hetero-cluster Janus dumbbells into hybrid cubosomes with internal double diamond structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b08016 (2018).

Ma, C. et al. A filled-honeycomb-structured crystal formed by self-assembly of a Janus polyoxometalate – silsesquioxane (POM – POSS) co-cluster Angewandte. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 54, 15699–15704 (2015).

Wang, F., Phonthammachai, N., Mya, K. Y., Tjiu, W. W. & He, C. PEG-POSS assisted facile preparation of amphiphilic gold nanoparticles and interface formation of Janus nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 47, 767–769 (2011).

Liu, H. et al. Manipulation of self-assembled nanostructure dimensions in molecular Janus particles. ACS Nano https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.6b01336 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. Two-dimensional nanocrystals of molecular Janus particles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 10691–10699 (2014).

Marciniec, B., Pietraszuk, C., Pawluć, P. & Maciejewski, H. Inorganometallics (transition metal-metalloid complexes) and catalysis. Chem. Rev. 122, 3996–4090 (2022).

Troegel, D. & Stohrer, J. Recent advances and actual challenges in late transition metal catalyzed hydrosilylation of olefins from an industrial point of view. Coord. Chem. Rev. 255, 1440–1459 (2011).

Walczak, M. et al. Hydrosilylation of alkenes and alkynes with silsesquioxane (HSiMe2O)(i-Bu)7Si8O12 catalyzed by Pt supported on a styrene-divinylbenzene copolymer. J. Catal. 367, 1–6 (2018).

Walczak, M. et al. Unusual cis- and trans- architecture of dihydrofunctional double-decker shaped silsesquioxane – design and construction of its ethyl bridged π-conjugated arene derivatives. New J. Chem. 41, 3290–3296 (2017).

Mituła, K., Dutkiewicz, M., Dudziec, B., Marciniec, B. & Czaja, K. A library of monoalkenylsilsesquioxanes as potential comonomers for synthesis of hybrid materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 132, 1545–1555 (2018).

Duszczak, J. et al. Distinct insight into the use of difunctional double-decker silsesquioxanes as building blocks for alternating A-B type macromolecular frameworks. Inorg. Chem. Front. 10, 888–899 (2022).

Mrzygłód, A., Rzonsowska, M. & Dudziec, B. Exploring polyol-functionalized dendrimers with silsesquioxane cores. Inorg. Chem. 62, 21343–21352 (2023).

Best, R. B. et al. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 3257–3273 (2012).

Saam, J., Ivanov, I., Walther, M., Holzhütter, H. G. & Kuhn, H. Molecular dioxygen enters the active site of 12/15-lipoxygenase via dynamic oxygen access channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 13319–13324 (2007).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 13319–13324 (2007).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. Lett. 38, 3098–3100 (1988).

Ditchfield, R., Hehre, W. J. & Pople, J. A. Self-consistent molecular-orbital methods. IX. An extended Gaussian-type basis for molecular-orbital studies of organic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 54, 720–723 (1971).

Reed, A. E., Weinstock, R. B. & Weinhold, F. Natural population analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 83, 735–746 (1985).

Frish, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.1 (Gaussian Inc., 2009).

Solvate Plugin, Version 1.5. https://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/plugins/solva at (2021).

The Energy Function - CHARMM tutorial. https://www.charmmtutorial.org/index.php/The_Energ at (2021).

Kirkpatrick, S., Gelatt, C. D. & Vecchi, M. P. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 220, 671–680 (1983).

Franz, A., Hoffmann, K. H. & Salamon, P. Best possible strategy for finding ground states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5219–5222 (2001).

Allen, M. P. & Tildesley, D. J. Computer Simulation of Liquids (Clarendon Press, 1989).

Phillips, J. C. et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 (2005).

Coutsias, E. A., Seok, C. & Dill, K. A. Using quaternions to calculate RMSD. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1849–1857 (2004).

Heyer, L. J., Kruglyak, S. & Yooseph, S. Exploring expression data identification and analysis of coexpressed genes. Genome Res. 9, 1106–1115 (1999).

Clustering plugin for VMD. http://physiology.med.cornell.edu/faculty/hweinste at (2019).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Petersson, G. A., Mohammad, A. & Laham, A. A complete basis set model chemistry. II. The total energies of open-shell atoms and hydrides of the first-row atoms. J. Chem. Phys. 9, 6081–6090 (1991).

Asaduzzaman, A., Runge, K., Muralidharan, K., Deymier, P. A. & Zhang, L. Energetics of substituted polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes: A DFT study. MRS Commun. 5, 519–524 (2015).

Asaduzzaman, A., Runge, K., Deymier, P. A. & Muralidharan, K. The role of aluminum substitution on the stability of substituted polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes. Zeitschrift Fur Phys. Chem. 230, 1005–1014 (2016).

Muya, J. T., Ceulemans, A., Gopakumar, G. & Parish, C. A. Jahn-teller distortion in polyoligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) cations. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 4237–4243 (2015).

Tomasi, J., Mennucci, B. & Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 105, 2999–3093 (2005).

Sokolnicki, T., Franczyk, A., Janowski, B. & Walkowiak, J. Synthesis of bio-based silane coupling agents by the modification of eugenol. Adv. Synth. Catal. 363, 5493–5500 (2021).

Stefanowska, K. et al. Selective hydrosilylation of alkynes with octaspherosilicate (HSiMe2O)8Si8O12. Chem. Asian J. 13, 2101–2108 (2018).

Spoljaric, S. & Shanks, R. A. Poly (styrene- b -butadiene- b -styrene)—dye-coupled polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes. Adv. Mater. Res. 125, 169–172 (2010).

Yuasa, S., Sato, Y., Imoto, H. & Naka, K. Thermal properties of open-cage silsesquioxanes: The effect of substituents at the corners and opening moieties. Bulletin Chem. Soc. Jpn. 92, 127–132 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the grant no. POWR.03.02.00-00-I026/16 co-financed by the European Union through the European Social Fund under the Operational Program Knowledge Education Development and grant Beethoven3 no. UMO-2018/31/G/ST4/04012 financed by National Science Center Poland. The calculations were performed in the Poznan Supercomputing and Networking Center.

Funding

The National Centre for Research and Development,POWR.03.02.00-00-I026/16, National Science Center Poland, UMO-2018/31/G/ST4/04012

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D.-K.—investigation and writing original draft; K.M.-Ch.—investigation and writing original draft; M.R.—investigation; W.J.—DFT calculations and molecular modelling; M.H.—conceptualization of DFT and molecular modelling; J.W.—conceptualization of hydrosilylation using Ir and other Pt catalysis; B.D.—conceptualization, review and editing, work supervision. All authors were involved in the preparation of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duszczak-Kaczmarek, J., Mituła-Chmielowiec, K., Rzonsowska, M. et al. Preparation of T8 and double-decker silsesquioxane-based Janus-type molecules: molecular modeling and DFT insights. Sci Rep 14, 18527 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69481-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69481-6