Abstract

The industrial production of cement contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, making it crucial to address and reduce these emissions by using fly ash (FA) as a potential replacement. Besides, Graphene oxide (GO) was utilized as nanoparticle in concrete to augment its mechanical characteristics, deformation resistance, and drying shrinkage behaviours. However, the researchers used Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to evaluate the compressive strength (CS), tensile strength (TS), flexural strength (FS), modulus of elasticity (ME), and drying shrinkage (DS) of concrete that was mixed with 5–15% FA at a 5% increment, along with 0.05%, 0.065%, and 0.08% of GO as potential nanomaterials. The concrete samples were prepared by using mix proportions of design targeted CS of about 45 MPa at 28 days. From investigational outcomes, the concrete with 10% FA and 0.05% GO exhibited the greatest CS, TS, FS, and ME values of 62 MPa, 4.96 MPa, 6.82 MPa, and 39.37 GPa, on 28 days correspondingly. Besides, a reduction in the DS of concrete was found as the amounts of FA and GO increased. Moreover, the development and validation of response prediction models were conducted utilizing analysis of variance (ANOVA) at a significance level of 95%. The coefficient of determination (R2) values for the models varied from 94 to 99.90%. Research study indicated that including 10% fly ash (FA) as a substitute for cement, when combined with 0.05% GO, in concrete yields the best results. Therefore, this approach is an excellent option for the building sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is now the 2nd most frequently useful product globally and is mostly employed in the construction industry1,2. It is extensively employed because of its versatility, durability, and accessibility3. High-strength concrete (HSC) or ultra-high performance concrete is often utilized in many construction projects due to the rapid expansion of structures including skyscrapers, roadways, dams, offshore footings, marine structures, and others4,5,6,7. This is particularly relevant in situations where the expansion of component dimensions would result in land waste8. One notable distinction between HSC and normal-strength concrete is in the relative proportions of Portland cement (PC) to other constituents, as well as the w/c ratio9,10. Put simply, more robust concrete requires a higher content of PC compared to less robust concrete. As a result, the heightened utilization of HSC leads to an increased demand for cement. Concrete emits carbon owing to the existence of PC11,12,13,14.

The process of cement manufacture is associated with certain limitations, such as elevated production costs and substantial energy consumption. Cement manufacturing generates significant quantities of CO2 and other GHG emissions15,16,17. The production of one metric ton of PC results in the emission of around one to 1.25 metric tons of CO2 into the environment18,19. Additionally, the manufacture of one metric ton of PC requires approximately 1.60 MWh of energy. PC production is seen as an expensive and environmentally conscious process20. Additionally, it is worth noting that the production of cement has resulted in environmental ramifications, as it is accountable for approximately 7 to 10% of global CO2 release21,22,23. The emission of GHG is the primary source of global warming and temperature rises24,25. Furthermore, the escalation in the usage of natural resources for the purpose of cement manufacture results in a shortage of renewable resources26. This study aims to solve two significant difficulties by exploring the potential application of by-products and underutilized elements as supplemental cementitious materials (SCMs) to partially replacement the quantity of PC in concrete or mortar27,28,29,30. The phenomenon of rapid development and industrialization has led to a surplus of by-products and unused ingredients. The handling and transportation of hazardous waste have been overwhelmed by the accumulation of by-products and trash generated by various industrial and agricultural enterprises. Consequently, there has been a decline in soil quality and adverse health effects for the local population. As a result, replacing a portion of the PC level with cementitious components not only reduces the need for PC as the primary binding agent and reduces the utilization of non-renewable resources, but also provides an opportunity to recycle unused resources that would otherwise be disposed of in landfills31,32. The municipality has the authority to define the types and quantities of by-products and underutilized resources produced, and the total quantity produced may vary significantly across different locations33. Their attributes may also vary. It is mandatory to use locally available by-products and waste as recycled building composites. This study investigates the use of fly ash (FA) SCMs in concrete.

Fly ash (FA) is a residual substance generated after the burning of coal that is mostly deposited at the uppermost section of boilers, notably in coal-fired power plants34,35. During or after the combustion process, the mineral particles or components not included in the coal undergo liquefaction, evaporation, consolidation, or agglomeration. The formation of sphere-like, amorphous FA particles occur as a result of surface tension forces during the fast-cooling process in the post-combustion region. Upon reaching an elevated temperature, the imprisoned volatile matter undergoes expansion, resulting in the formation of a hollow cenosphere. Certain residues have the potential to undergo crystallization, while others may have a glassy appearance, depending on composition of the contaminants and the conditions of both heating and cooling36. FA is a specialty SCM that is utilized in matrix37,38. The accumulation of FA has been shown to enhance the flow of concrete39, decrease thermal fracture during the early stages, and enhance the properties related to hardened and toughness of composites, particularly in the later stages40,41.

The reaction between the amorphous silica existing in FA and Ca(OH)2 results in the development of C–S–H42,43. According to reference44, the pozzolanic response of FA enhances its efficacy not only in concrete but additionally in several other building applications. The pozzolanic procedure results in a much longer duration of strength development compared to conventional concrete45. Furthermore, it has been shown that FA enhances the workability of concrete via the mitigation of bleeding46. Prior studies have confirmed that the incorporation of FA into conventional and reused aggregate concrete may enhance its long-term CS47. The growth of strength in FA, however, is contingent upon its chemical and physical properties. Investigate has revealed that FA with a smaller particle size exhibits a higher CS compared to FA with a larger particle size48. The presence of the binder induces shrinkage in the concrete throughout its hydration phase, and a high degree of shrinkage may lead to the development of significant fractures in concrete. FA is advantageous for reducing shrinkage49. The usage of a substantial amount of FA in concrete, mostly by substituting 50% of PC with FA, has been seen to provide a 30% decrease in shrinkage in comparison to conventional concrete50.

The utilization of nanoparticles has gained important attention in the field of concrete bonding due to their outstanding features, containing a significant specific surface area, improved response pace, and minimal quantity needed51,52,53. Hence, graphene oxide (GO) was utilized as the nanoparticle in this study. GO is a nanoplatelet with a two-dimensional structure. The inherent characteristics of GO exhibit similarities to those of graphene. These include a two-dimensional structure composed of atom-thick sp2 bonds, a favorable elastic modulus of 1100 GPa, an outstanding thermal conductivity of 3000 W m−1 K−1, a larger specific surface area of 2600 m2/g, a commendable tensile strength of 125 GPa, and favorable stiffening54,55,56. Moreover, GO exhibits a extensive range of functional groups containing oxygen on both the bottom and outer surfaces, such as epoxy compounds, ketone, carbonyls, hydroxyls, and carboxylic acids. GO has many notable benefits in comparison to other nanoparticles. These benefits include its capacity to impede fracture development at the nanoscale, its capability to expedite the process of hydration, and its facile distribution in liquid owing to presence of functional groups (FG) with hydrophilic characteristics on the situation basal surfaces.

Currently, the majority of researchers are studying the influence of GO on the concrete characteristics and other fields57. Their attention is mostly on the influences of GO on mechanical and durability behavior, hydration, and dispersal of the material. Wang et al.58 have shown that GO contributes to the process of cement hydration by enhancing the rate of production, growth, and segregation of hydrated products. This facilitated the procedure of hydration and enhanced the arrangement of crystals, leading to significant rises of about 91% in FS and 53% in CS of the mortar, correspondingly. Mohammed et al.59 have shown that GO has the potential to enhance the pore structure of composites, directing to a considerable improvement in durability. Additionally, their study has revealed that GO may adapt the cement composites to display exceptional resistance to freezing and thawing.

Furthermore, there are so many studies performed on FA as SCM and GO as a nanomaterial separate in concrete. But there is very limited investigation performed on concrete combined with GO as nanomaterial along with FA as SCM by using RSM modelling. Therefore, this research examines the impact of GO as a nanomaterial and FA as a SCM on the mechanical, deformation, and drying shrinkage characteristics of concrete. The aim is attained by employing response surface methodology (RSM) to create mixtures utilizing the GO and FA as input factors. RSM-based predictive algorithms are then developed by applying the real-world information produced, which is then analysed through ANOVA. In addition, an optimization with multiple goals is performed, followed by investigational validation.

Experimental program

Materials

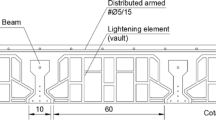

The binding agent utilized consists of a combination of Portland cement (PC) according to ASTM C150 and fly ash (FA) containing a low calcium concentration. This combination is categorized as class F conferring to ASTM C618, with an overall oxide (Al2O3 + Fe2O3 + SiO2) content over 70%, as illustrated in Table 1. The FA is used as SCM in concrete. The sand utilized for the fine aggregate having 4.75 mm in size, whereas the coarse aggregate employed in the research study possesses a size of 20 mm. The properties of aggregates are summarized in Table 2. In the study, a slurry consisting of a distribution of GO-water with a concentration level of 2.5 wt.% was employed. Moreover, the superplasticizer (SP) was utilized in the concrete which contains specific gravity of 1.08 and a pH reading of 6.20. The mixtures were made with drinking water that met the specifications outlined in ASTM C1602. Furthermore, the materials used in concrete are mentioned in Fig. 1 and the sieve analysis of aggregates are mentioned in Fig. 2.

Mix design produced by RSM and material proportioning

The RSM modelling was developed and analyzed the experiments information60. The model employs a dependent factor, which is also referred to as the response, as its output parameter, and distinct variables, which serve as input parameters. The RSM evaluates the impact of the independent aspects and the association between these factors on the variable that is dependent. It is used across multiple fields, such as the design, modeling, and optimization of concrete. The study used GO incorporation at cement weights of 0.05%, 0.065%, and 0.08%, as well as FA as substitutes for cement at 5%, 10%, and 15%, as input elements for the RSM. A total of thirteen mixtures were produced by combining eight different input components and repeating the core points five times, following the central composite design arrangement. The concrete mix percentage was determined to conduct several mix trials in order to get the desired compressive strength of about M45 with a water-to-cement ratio of 0.36 by using DOE method. The first dosage for each mixture included using 1% of SP by weight of PC. Nevertheless, due to the fact that GO diminishes the flowability of concrete, its proportion was adapted based on the particular demands of each mix to enable a workable enough mixture. Table 3 depicts the combinations established by the RSM and the associated quantities of constituents utilized.

Mixing and testing procedures

Mixing

It conducted the blending process with a concrete mixer, adjusting the speeds granting to the particular constituents incorporated at each step. The mixing procedure started by including the dry ingredients, like PC, FA, CA, and sand and mixing at a low velocity of 30 RPM for a period of 2 min. Afterwards, a mixture containing water, 1% SP, and GO was put in mixture for three-minute mixing period at a rapid rotating velocity of 60 RPM. Consistent with previous studies61, GO was mixed with SP to aid the distribution of GO without requiring sonication. The SP was included in mixtures with a greater concentration of GO in order to offset the reduction in fluidity and deliver a practical mixture. The fresh concrete was put into several specimens and after 24 h, all specimens were demoulded. After demoulding, all samples were put in curing tank for 28 days for the purpose of conducting mechanical and deformation testing.

Mechanical characteristics tests

The evaluations were achieved on the samples after a 28-day curing period in water. Three cubical specimens (100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm) were subjected to the compressive strength assessment for each mixture at 28 days. The experiment was assessed via a UTM with a capability of 3000 kN by verifying the BS EN 12390-362. The approach described by JSCE63 was used to perform a direct tensile examination on a dog-bone-shaped sample measuring 420 mm × 120 mm × 30 mm. The experiment was performed on UTM with a capability of 200 kN. The UTM was fitted with integrated linear variable-diameter transistors and a data logger. The assessment information was then sent to a computer, which analyzed and presented the values in real-time. Similarly, the flexural assessment was conducted on 500 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm beam specimens utilizing the same kind of UTM by following the BS EN 12390-564 standard, at 28 days. Three of the samples were prepared to testing for each mixture, and the average result of each flexural attribute was reported. The experimental set up for mechanical characteristics are revealed in Fig. 3.

Deformation properties tests

The static technique was used to measure the modulus of elasticity (ME) in agreement with the specifications outlined in ASTM C46965. The assessment was performed on four cylinders (300 mm × 150 mm) for each mixture. The compressive strength was determined using two of the cylinders, while the ME was determined using the remaining two cylinders. The experimental setting included a compressormeter that was outfitted with dial indicators attached to sample. The dial indicators served to measure the longitudinally and laterally deformations of the sample when subjected to a force that was 40% of the highest load determined from the compressive measurement. The ME was computed through Eq. (1)66.

where E is Young's modulus, GPa, σ2 is the Stress related to 40% of the final load or final Stress, MPa, σ1 is the Stress related to a longitudinal strain of 0.000050, MPa, \({\varepsilon }_{{\sigma }_{2}}\) is the lateral strain at mid-height of the specimen at a stress, σ2.

Specimens with measurements of 280 × 50 × 30 mm were used to assess the shrinkage of GO-concrete compositions utilizing FA as cementitious material, in agreement with the procedures stated in ASTM C157/C157M67. Two specimens of each GO-concrete mixture were fabricated, subjected to curing under standard laboratory circumstances, and assessed for changes in length on a weekly basis over a period of 90 days utilizing a length comparator. The density of the specimens was observed and recorded until the disparity between two successive measurements was found to be below 0.5%. Furthermore, the experimental set up of deformation properties are mentioned in Fig. 4.

Outcomes and discussions

Compressive strength (CS)

Figure 5 demonstrates the CS outcomes of concrete combined with several concentrations of GO as a nanomaterial, in conjunction with FA as SCM. The graph depicts the arrangement of mixes with identical GO content, arranged in increasing order based on the incorporation of fly ash for each group. Figure 5 displays the mean outcomes of the five repeating mixtures of the CCD central points (0.065% GO and 10% FA), which are referred to as MCP for clarity. It is evident that the inclusion of 0.065% GO and 10% FA led to in an enhancement in CS. The observed phenomenon may be owing to the ongoing hydration process, which results in the making of more C–S–H gel, indicating to an upward trajectory68. The strength exhibited a substantial increase across all fiber volume fractions as the GO concentration rose from 0 (control) to 0.05%. A substantial rise of 16.98% is noted between the control group (M0) and the experimental group (M2) (0.05%, 10%) at 28 days. The observed improve in CS when using GO may be due to the combined physical and chemical impacts shown by the nanoparticle. The robust hardened concrete combined with GO play a vital character in improving the CS. The presence of wrinkled GO nanosheets could make the composite stronger and less likely to crack by making it easier for different reaction products to connect at different stages. Moreover, due to its nanoscale nature, GO has a high affinity for the pores within the cement matrix, leading to enhanced densification and, therefore, improved mechanical properties69. From a chemical perspective, the huge surface area of GO assists as an ideal location for the formation of hydration products. The general opinion is that oxygen functional groups of GO interact with the chemicals in cement, leading to the development of flower-like crystals within the composite. This interaction is considered to boost the strength of the combination70.

Nevertheless, with the increase in GO to 0.65% and 0.08%, the observed rise in compressive strength at 0.05% steadily decreased, particularly when larger FA concentrations were present. Although MCP (0.065%, 10%) exhibits a somewhat greater strength compared to the CM at 28 days, it is comparatively smaller than M2 (0.05%, 10%), which has a lower GO concentration but an equivalent FA level. The strength of all the subsequent mixtures in the 0.065% and 0.08% GO groups was less than CM. The extent of the strength loss improved as the FA as SCM rises. The rationale for this phenomenon may be accredited to the adverse consequences associated with increased dosages of GO. These consequences include issues related to the dispersing and agglomeration of nanoplatelets, which have been seen to impede the effective use of nanomaterials in boosting the strength of combinations71. Additional research has revealed that agglomerated GO nanoplates are less efficient at increasing the mechanical characteristics of the matrix compared to widely distributed GO sheets. This is because the latter utilizes a larger surface area to augment cement hydration via the action of nuclei72. The outcomes are in line with the studies supported by Wang et al.58 and Kang et al.73.

Tensile strength (TS)

The TS assessment on dog-bone samples determines the tensile characteristics of the GO-concrete with FA as SCM after 28 days. The present study focused on evaluating the tensile characteristics, specifically the ultimate TS. It refers to the highest TS of samples at the failure point, which is determined by the strain value associated with the greatest tensile strength. Figure 6 displays the average TS value derived from three samples for each GO-concrete, which incorporates different proportions of FA as a cementitious ingredient. The findings indicate a notable enhancement of 17% in TS when comparing the CM to the mixture including 0.05% GO at 10% FA as SCM. The observed enhancement in strength at lower concentrations of GO and 10% FA is ascribed to the nanoplatelets' potential to occupy pores and accelerate the hydration process, causing in augmented formation of C–S–H gel. Additionally, this improvement can be accredited to the strengthened bonding between the constituents of the concrete, leading to an enhanced inter-transition zone74. While the enhancement in TS is not as significant as seen in the M2 sample, it still surpasses that of the control group when 5% and 15% of FA are added in the 0.05% GO group. The increase in TS is accompanied by the greater specific surface area of FA compared to PC. However, when FA is added as a SCM, the strength decreases. This reduction in strength may be due to the small amount of Ca(OH)2 in the HSC, which acts as a dilution effect of FA. The inclusion of 0.065% GO resulted in a 17% enhancement in TS than CM, particularly when 10% FA was used as SCM. Nevertheless, the rise is negligible when considering a 15% increase in FA adds. The tensile strength of the combination decreased when the GO was further increased to 0.08 in comparison to CM. The rationale for this phenomenon may be accredited to the adverse consequences associated with increased dosages of GO. These consequences include issues related to the dispersing and agglomeration of GO, which have been seen to impede the effective use of nanomaterials in boosting the strength of composites71. The outcomes are in line with the studies supported by Bheel et al.75,76.

Flexural strength (FS)

Figure 7 displays the FS outcomes of GO blends of concrete when coupled with different proportions of FA as SCM. The FS of the blended concrete mixes, including GO and FA, varies from 4.62 to 6.61 MPa. The data indicates a significant rise in flexural strength when 0.05% GO and 10% FA are added together, in comparison to the control. As the content of FA grows up to 10 and GO up to 0.05% as nanomaterials, there is an observed rise in flexural strength. The GO nanoparticles have a nano-reinforcing action that directly impacts the micromechanical characteristics. The 2D nanomaterials at the nanoscale level effectively intercept and bridge the nano fractures, therefore impeding their propagation. The authors Li et al.77 have highlighted the significance of effective transfer of stresses between the GO and the mortar, as well as across the nano cracks, at the ITZ. The filling mechanism and amplification of the hydration process are attributed to the nuclei and template influences of GO78. Though, the FS is getting decreases when the FA increases due to the inclusion of SCM and GO. As previously mentioned, the inclusion of higher levels of GO is shown to be counterproductive as a result of agglomeration and sliding phenomena. An excessive amount of GO adversely impacts the fresh concrete and compactness of concrete owing to self-curing properties exhibited by the enormous surface area of GO. This self-curing impact leads to an increase in cement flocculation, therefore capturing free water. The researchers, Bheel et al.76, made an analogous finding.

Modulus of elasticity (ME)

Figure 8 demonstrations the ME for GO-concrete compositions with different amounts of FA as SCM. The ME values of the mixtures exhibit a range of 32.40 to 39.37 GPa. The composite's ME exhibits an optimal gain of 8.20% in comparison with the CM, which has a ME of 36.40 GPa. The observed increase in ME surpasses the about 29% rise documented by Mohammed et al.79 when the composites was modified with nano silica. In general, the CS of concrete is linked to its ME80. Several factors, including the dimension, form, quantity, and ME of the aggregates, as well as the ITZ located between the aggregates and the binding material, influence the ME of composites. Moreover, the integration of GO caused in enhanced toughness and compactness of the hardened cementitious matrix. Consequently, this resulted in superior stress transmission at the interface between the aggregates and the hardened cement mix, resulting in enhanced ME measurements. The decrease in the ME readings seen with an increased quantity of FA may be ascribed to the buildup of a substantial amount of FA, resulting in the formation of a hard mixture. The increased concentration of FA in concrete leads to a greater absorption of water, resulting in the development of a hard mixture. This is attributed to a shortage of water as the quantity of FA in mixture rises, which causes the concrete to segregate. Concrete segregation decreases the ME of concrete. In contrast to the control and ME findings of concrete blends from earlier research81,82, the ME readings observed for all GO inclusion groups exhibit a high level of quality. Therefore, this demonstrates the capacity of GO alteration in concrete and results in a substantial increase in ME. Bheel et al.75,76 conducted a comparable observation.

Drying shrinkage (DS)

The reduction in volume resulting from the shrinkage strain, known as drying shrinkage, is attributed to water loss occurring throughout the capillary openings of concrete material. Figure 9 demonstrates a significant decrease in DS as the combination of FA and GO increased. The shrinkage readings for GO-Concrete vary from 0.038 to 0.062%, which is considerably lesser than the shrinkage measurement for the CM specimen, which is 0.07%, and the published range of shrinkage readings for concrete, which is from 1200 × 10−6 to 1800 × 10−683. The DS of the CM and the GO-concrete mixed with 15% FA mix, which exhibits its smallest drying shrinkage value (M11), demonstrates a reduction of 45.71%. The decrease in DS is credited to the reduction and refinement of the pore structure in the matrix, which is a consequence of the densification action of GO84. In addition, the existence of many reactive FG on the surface of GO resulted in enhanced PC hydration, leading to an increase in density of PC paste and stability of volume while simultaneously reducing DS. Furthermore, the hydrophilic nature of GO, coupled with their extensive surface area, enables them to effectively absorb a significant quantity of water throughout the mixing procedure. This water is subsequently released back into the combination, thereby enhancing the hydration procedure of PC. This is achieved by promoting the production of hydration products, enhancing the density of the matrix, and reducing DS. Conversely, the DS of all GO-concrete combinations is consistently lesser than CM, regardless of the incorporation of GO and FA. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of GO in mitigating the problem of excessive DS in concrete. A analogous discovery was conducted by Bheel et al.76 and Abdulkadir et al.85.

RSM modelling

Analysis of variance (ANOVA)

The outcome of experiments was used to construct and verify empirical response-predictive algorithms. According to the relations between the input elements and their effect on the intended result, the mathematical framework has the ability to adopt any of the two forms specified in Eqs. (2) and (3)86,87,88 for a linear or quadratic connection, correspondingly.

Equations (4–8) were obtained from RSM modelling for mechanical and deformation properties of concrete. These equations provide the developed models from RSM modelling. Besides, quadratic representations were determined to be more appropriate for analysing the CS, TS, FS, ME and DS of GO-concrete mixes combined with fly ash as cementitious material. This decision was based on SMSS, which included a greater number of significant additional terms and did not exhibit any aliasing. The provided models are encoded into factors, with the smallest, middle, and highest values of the input components represented by − 1, 0, and + 1, consistently89,90,91.

where A is the GO as nanomaterial and B is the fly ash by the weight of cement.

The models underwent ANOVA with a confidence level of 95%. Therefore, models and its terms that had a possibility of smaller than 5% were deemed to be statistically significant92,93. Table 4 succinctly displays the ANOVA result. All of the developed approaches have arithmetical significance, as evidenced by a likelihood value (P-value > F) lower 0.005. The significance of the model terms is determined by assessing whether the p-value > F of the term is smaller than or greater than 5%, as seen in Table 4. On the other hand, it is crucial that the p-value associated with the 'Lack of Fit' be deemed 'not significant' (> 5%) in order for approach to be considered adequate88,92. Nevertheless, when evaluating the diagnostic tools of other models, it is evident that all models are sufficiently robust for their intended purpose.

Furthermore, Table 5 presents additional model validation characteristics that were taken into account throughout the investigation. All the models have a relatively high R2, indicating the degree to which the produced approach accurately agrees to the actual information90. The coefficient R2 ranges from 0 to 1, with a value of 1 or a value close to 1 being considered the most favourable94,95. The R2 values for all the approaches fluctuated from 94 to 99%, suggesting that the selected models accurately represent the data. In order to achieve a high level of accuracy in predicting the response, it is essential that the adjusted R2 and anticipated R2 exhibit a maximum difference of 0.287,88. Upon examination of the Adj. R2 and Pred. R2 values for all the models, it is evident that this threshold is met. In addition, a developed model must have a minimum precision (Adeq. Precision) of four or higher92,93. Moreover, all the produced approaches had an Adeq. precision of more than 10, representing their robustness and ability to properly anticipate the responses.

Model diagnostics and response surface plots

The actual vs. projected graph is a model diagnostic technique often used in RSM to assess the quality of the created model. This graph visually represents the efficacy of the model and allows for a comparison with the null model76. The data points ought to conform to the 45º fitting line, accompanied by small confidence intervals, in order to achieve a satisfactory fit76. Conversely, the outcome of the interplay between the factors and the response may be effectively represented via the use of either a 2D graph or a 3D diagram. The 3D chart conveys identical information to the 2D chart, however, from a 3D standpoint. Figures 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14 provide the diagnostic chart comparison the actual values with the predictable information, and the 3D response surface chart for entirely response estimate prototypes that were built in this study. The placement of the statistics points with the line of fit in the actual against anticipated charts is evident across all constructed models, indicating a robust relationship between the investigational findings and the predictable response information generated by the mathematical models.

Concerning the 3D charts, the use of color coding shows different zones on the surface graph that correspond to different levels of response intensity caused by the input factors interacting with each other. The areas with the largest response magnitudes are exposed by the red zones, whereas the regions with the lowest response concentrations are represented by the blue areas. The obtained graphs demonstrate that the relations between the input parameters and their impact on the responses align closely with previous study on the effects of parameters on the mechanical, deformation and DS characteristics of GO-concrete mixtures.

Multi-objective optimization

The objective of optimization is to generate the intended outcome by maximizing the optimum standards of the constraints. To accomplish the intended purpose, goals are established for the factors with various criteria and levels of significance. The optimization is evaluated utilizing the desirability rate (0 ≥ dj ≥ 1). As the result improves, the value approaches to 1.076,92,93.

The objective functions for optimization were constructed in this case, as shown in Table 6, which also displays the outcomes. The findings indicate that by adding GO and FA at levels of 0.05% and 10%, the optimal values for CS, TS, FS, ME, and DS were achieved, with values of 61.63 MPa, 4.93 MPa, 6.78 MPa, 39.29 GPa, and 0.055%, respectively. These values were obtained at a high desirability value of 77.50%. The optimization solution ramps and desirability outcomes are shown in Figs. 15 and 16, correspondingly.

Investigational validation

The concluding stage of the RSM study entails the empirical verification of the constructed models and the optimization solutions via the generation of specimens through the suggested optimized input parameters. Following a 28-day curing, the specimens underwent testing, and the acquired experimental findings were then compared to the expected outcomes derived from the optimization process. Equation (9) was used to compute the experimental error, and the outcomes are displayed in Table 7. The experimental findings revealed a high degree of correspondence with the expected outcomes, with a percentage error of less than 10% across all replies. Therefore, the Eqs. (4–8) that have been created may be used to accurately forecast the replies.

Here, \(\delta \) denotes the percentages Error, \({\vartheta }_{E}\) indicates the experimental outcome, and \({\vartheta }_{P}\) shows the predicted outcome.

Comparing the RSM modelling outcome with prior research

A model analysis of the outcome was undertaken to examine the influence of input parameters on predicting the result. Every model must undergo statistical verification and validation to determine its compatibility with the findings from the experiment. The statistical significance and adequacy of the suggested approach are assessed using different methods derived from the ANOVA acquired from the RSM. These approaches include P-values, PRESS, R2, adjusted R2, predicted R2, and adequate precision96. Probability tests were used to assess the statistical importance of all approaches and their individual terms. If the likelihood of the Fisher statistical outcome for an algorithm or its term is below 0.05, then the prototypical or term is considered statistically important as shown in Table 869,97,98. There was a significant correlation between the mathematical models and the parameters. The significance level of each term in the framework is assessed. Any prototypical term with a p-value less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant in the model. The backward elimination procedure can improve the approach by eliminating a parameter from the model if the p-value exceeds 0.05, indicating its lack of statistical significance.

Calculating R2 using the PRESS can demonstrate the model's proven efficiency, appropriateness, and competency. R2, a number ranging from 0 to 1, quantifies the degree of fit between the experimental results and the predicted outcome of the model as shown in Table 869,76,97. Values approaching 1 show a high level of conformity between the data and the model, indicating the model's predictive capability is stronger. A R2 score of 1 show that the model effectively accounts for all the variability in the experimental data relative to the mean, while a score of 0 proposes that the prototypical does not describe any of the variability. Once R2 has been confirmed, it is crucial to analyse the difference between the expected and modified R2 values. The adjusted R2 is the amended version of the R2 that takes into account the number of predictors in the model. On the other hand, the anticipated R2 measures the extent to which the investigational data differs from the predicted approaches. A good model should have a discrepancy of less than 0.2 between the adjusted and forecasted R2 values69,76. If the discrepancy exceeds 0.2, it indicates a problem with either the approach or the data. When encountering this issue in the model, possible remedies include examining for outliers, reducing the complexity of the model, transforming the model, or adjusting the polynomial order of the model99,100. The dependability of the model was further examined by comparing standard deviations to means.

The modest standard deviations of the models in relation to their mean results further reinforced their suitability and accuracy for predictions. The mean prediction error may be matched to the anticipated outcomes at the design points utilising the appropriate precision, resulting in a signal-to-noise ratio that matches the range of anticipated outcomes at the design points to the average prediction error. If the model's accuracy exceeds 4, it may be effectively used to explore the design space101.

The multi-objective optimisation of RSM validates and clarifies the desirability of a solution. Desirability is a technique that uses a multiple-response approach to define desired response ranges using a 0–1 objective function as shown in Table 876. An objective function value of 1 or near 1 shows the successful attainment of optimal combinations of various optimisation objectives with minimal or no significant errors, leading to expected values that match the anticipated outcomes96,102.

Conclusion

This research aimed to examine the impact of GO as a nanomaterial on mechanical, deformation, and drying shrinkage characteristics of concrete combined with fly ash as replacement for PC by apply RSM modelling. The following key points are summarized below:

-

The optimum CS, TS and FS were observed by 62 MPa, 4.96 MPa, and 6.82 MPa at 0.05% of GO and 10% of FA together in concrete at 28 days consistently.

-

The ME was enhanced by 39.37 GPa when adding 0.05% GO as a nanomaterial and 10% FA as SCM in concrete at 28 days of curing. The ME is improved as the concentration of GO increases in concrete combined with the various contents of fly ash.

-

The DS of concrete is getting reduced when GO as nanomaterial and FA as SCM increases. This decrement in shrinkage behaviour is associated to the pore filling effect of GO and FA and make the concrete hard.

-

Response-predictive models were generated and validated via ANOVA and experimentally. The developed models have high R2 values, fluctuating between 94 and 99%. The optimisation of output responses was attained at 0.05% of GO and 10% FA together, achieving a desirability value of 77.50%.

-

From the investigational results, it is observed that the use of 0.05% of GO as nanomaterial and 10% of FA as SCM provides outstanding results therefore it is recommendation for structural applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kanagaraj, B., Anand, N., Alengaram, U. J., Raj, S. & Jayakumar, G. Promulgation of engineering and sustainable performances of self-compacting geopolymer concrete. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106093 (2023).

Kanagaraj, B., Alengaram, U. J., Raj, S. & Tattukolla, P. B. K. Performance evaluation on engineering properties and sustainability analysis of high strength geopolymer concrete. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105147 (2022).

Bheel, N., Memon, F. A. & Meghwar, S. L. Study of fresh and hardened properties of concrete using cement with modified blend of millet husk ash as secondary cementitious material. Silicon 13, 4641–4652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-020-00794-7 (2021).

Wei, J. et al. Seismic performance of concrete-filled steel tubular composite columns with ultra high performance concrete plates. Eng. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.115500 (2023).

Huang, H., Yuan, Y., Zhang, W. & Zhu, L. Property assessment of high-performance concrete containing three types of fibers. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40069-021-00476-7 (2021).

Sun, L. et al. Experimental investigation on the bond performance of sea sand coral concrete with FRP bar reinforcement for marine environments. Adv. Struct. Eng. 26, 533–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/13694332221131153 (2023).

Zhao, R., Li, C. & Guan, X. Advances in modeling surface chloride concentrations in concrete serving in the marine environment: A mini review. Buildings https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14061879 (2024).

Hosozawa, H.O. Structural design of an ultra high-rise building using concrete filled tubular column with ultra high strength materials. In 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering (2012).

Ma, B. et al. Utilization of waste marble powder in cement-based materials by incorporating nano silica. Constr. Build. Mater. 211, 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.248 (2019).

Sounthararajan, V. M. & Sivakumar, A. Effect of the lime content in marble powder for producing high strength concrete. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 8, 260–264 (2013).

Pratap, B., Mondal, S. & Hanumantha Rao, B. NaOH molarity influence on mechanical and durability properties of geopolymer concrete made with fly ash and phosphogypsum. Structures https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105035 (2023).

Pratap, B., Mondal, S. & Hanumantha Rao, B. Development of geopolymer concrete using fly ash and phosphogypsum as a pavement composite material. Mater. Today Proc. 93, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.06.207 (2023).

Bahari, A. et al. Experimental studies on rheological, mechanical, and microstructure properties of self-compacting concrete containing perovskite nanomaterial. Struct. Concr. 23, 564–578. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202000548 (2022).

Choudhary, R., Gupta, R., Alomayri, T., Jain, A. & Nagar, R. Permeation, corrosion, and drying shrinkage assessment of self-compacting high strength concrete comprising waste marble slurry and fly ash, with silica fume. Structures. 33, 971–985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2021.05.008 (2021).

Golewski, G. L. Green concrete based on quaternary binders with significant reduced of CO2 emissions. Energies. 14, 4558 (2021).

Channa, S. H., Mangi, S. A., Bheel, N., Soomro, F. A. & Khahro, S. H. Short-term analysis on the combined use of sugarcane bagasse ash and rice husk ash as supplementary cementitious material in concrete production. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 3555–3564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15877-0 (2022).

Keerio, M. A., Saand, A., Kumar, A., Bheel, N. & Ali, K. Effect of local metakaolin developed from natural material soorh and coal bottom ash on fresh, hardened properties and embodied carbon of self-compacting concrete. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 60000–60018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14960-w (2021).

Bheel, N. et al. Use of marble powder and tile powder as cementitious materials in concrete. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 10, 5448–5451. https://doi.org/10.48084/etasr.3378 (2020).

Naidu, P.V. & Pandey, P.K. Replacement of cement in concrete. Int. J. Environ. Res. Dev. 4, 91–98 http://www.ripublication.com/ijerd.htm (2014).

Neville, A.M. Properties of Concrete. 14, 15, 35, 83, 191, and 192 (Pearson Education Asia Pte. Ltd., 2000).

Andrew, R. M. Global CO2 emissions from cement production. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 10, 195–217. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-10-195-2018 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Analysis of CO2 emission for the cement manufacturing with alternative raw materials: A LCA-based framework. Energy Proc. 61, 2541–2545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2014.12.041 (2014).

Xiao, J., Xiao, Y., Liu, Y. & Ding, T. Carbon emission analyses of concretes made with recycled materials considering CO2 uptake through carbonation absorption. Struct. Concr. 22, E58–E73. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.201900577 (2021).

Golewski, G. L. Comparative measurements of fracture toughgness combined with visual analysis of cracks propagation using the DIC technique of concretes based on cement matrix with a highly diversified composition. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 121, 103553 (2022).

Sun, C., Chen, Q., Xiao, J. & Liu, W. Utilization of waste concrete recycling materials in self-compacting concrete. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104930 (2020).

Jhatial, A. A., Goh, W. I., Mastoi, A. K., Traore, A. F. & Oad, M. Environmental assessment and mechanical properties of polypropylene fibres reinforced ternary binder foamed concrete. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 2985–3007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15076-x (2022).

Diao, X. et al. Enhanced dynamic compressive performance of silicon carbide whiskers-modified mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136626 (2024).

Dai, T. et al. Waste glass powder as a high temperature stabilizer in blended oil well cement pastes: Hydration, microstructure and mechanical properties. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137359 (2024).

Fang, B. et al. Evaluation of early crack resistance performance of concrete mixed with ternary minerals using temperature stress testing machine (TSTM). J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142780 (2024).

Ke, G., Li, Z. & Jiang, H. Study on long-term solidification of all-solid waste cementitious materials based on circulating fluidized bed fly ash, red mud, carbide slag, and fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136284 (2024).

Sadeghi-Nik, A., Bahari, A., Nik, A.S., Club, Y.R., Branch, J., Sadeghi Nik, A. & Amiri, B. Nanostructural properties of cement-matrix composite. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. Res. 1, 2167–2173. https://www.textroad.com (2011).

Sadeghi-Nik, A., Bahari, A., Khorshidi, Z. & Gholipur, R. Effect of lanthanum oxide on the bases of cement and concrete. In Third International Conference on Construction Developing Countries. 4–6 (Advancing Civil, Architectural Technology and Construction Management, 2012).

Khalilpasha, M.H., Sadeghi-Nik, A., Lotfi-Omran, O., Kimiaeifard, K. & Amirpour-Molla, M. Sustainable development using recyclable rubber in self-compacting concrete. In Third International Conference on Construction Developing Countries. 580–585 (Advancing Civil, Architectural Technology and Construction Management, 2012).

Li, G. et al. Fly ash application as supplementary cementitious material: A review. Materials (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15072664 (2022).

Usanova, K. & Barabanshchikov, Y. G. Cold-bonded fly ash aggregate concrete. Mag. Civ. Eng. 95, 104–118. https://doi.org/10.18720/MCE.95.10 (2020).

Barbara, G. K. & Ann, G. K. Fly ash characterization by SEM-EDS. Fuel. 85, 2537–2544 (2006).

Sua-iam, G. & Makul, N. Rheological and mechanical properties of cement-fly ash self-consolidating concrete incorporating high volumes of alumina-based material as fine aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 95, 736–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.07.180 (2015).

Amran, M. et al. Fly ash-based eco-efficient concretes: A comprehensive review of the short-term properties. Materials (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14154264 (2021).

Pratap, B., Mondal, S. & Rao, B. H. Mechanical and durability assessment of phosphogypsum- bauxite residue—Fly ash-based alkali-activated concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134670 (2024).

Şahmaran, M. & Li, V. C. Durability properties of micro-cracked ECC containing high volumes fly ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 39, 1033–1043 (2009).

Uthaman, S. et al. Enhancement of strength and durability of fly ash concrete in seawater environments: Synergistic effect of nanoparticles. Constr. Build. Mater. 187, 448–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.214 (2018).

Li, X. et al. A systematic review of waste materials in cement-based composites for construction applications. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103447 (2022).

John, E., Matschei, T. & Stephan, D. Nucleation seeding with calcium silicate hydrate—A review. Cem. Concr. Res. 113, 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.07.003 (2018).

González, A., Navia, R. & Moreno, N. Fly ashes from coal and petroleum coke combustion: Current and innovative potential applications. Waste Manag. Res. 27, 976–987. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X09103190 (2009).

Saha, A. K. & Sarker, P. K. Sustainable use of ferronickel slag fine aggregate and fly ash in structural concrete: Mechanical properties and leaching study. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 438–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.035 (2017).

Yao, Z. T. et al. A comprehensive review on the applications of coal fly ash. Earth-Sci. Rev. 141, 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.11.016 (2015).

Berndt, M. L. A links open overlay panel, properties of sustainable concrete containing fly ash, slag and recycled concrete aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 23, 2606–2613 (2009).

Chindaprasirt, P., Jaturapitakkul, C. & Sinsiri, T. Effect of fly ash fineness on compressive strength and pore size of blended cement paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 27, 425–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2004.07.003 (2005).

Lee, H. K., Lee, K. M. & Kim, B. G. Autogenous shrinkage of high-performance concrete containing fly ash. Mag. Concr. Res. 55, 507–515. https://doi.org/10.1680/macr.2003.55.6.507 (2003).

Atis, C. D. High-volume fly ash concrete with high strength and low drying shrinkage. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 15, 153–156 (2003).

He, H. et al. Deciphering size-induced influence of carbon dots on mechanical performance of cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136030 (2024).

He, H. et al. A general and simple method to disperse 2D nanomaterials for promoting cement hydration. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136217 (2024).

He, H. et al. Exploring green and efficient zero-dimensional carbon-based inhibitors for carbon steel: From performance to mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134334 (2024).

Long Dong, L., Ge Chen, W., Deng, N. & Hao Zheng, C. A novel fabrication of graphene by chemical reaction with a green reductant. Chem. Eng. J. 306, 754–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2016.08.027 (2016).

Horszczaruk, E., Mijowska, E., Kalenczuk, R. J., Aleksandrzak, M. & Mijowska, S. Nanocomposite of cement/graphene oxide—Impact on hydration kinetics and Young’s modulus. Constr. Build. Mater. 78, 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.12.009 (2015).

Kuilla, T. et al. Recent advances in graphene based polymer composites. Prog. Polym. Sci. 35, 1350–1375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2010.07.005 (2010).

Jatoliya, A., Saha, S., Pratap, B., Mondal, S. & Rao, B. H. Assessment of bauxite residue stabilized with lime and graphene oxide as a geomaterial for road applications. Soils Rocks https://doi.org/10.28927/SR.2023.003722 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Influence of graphene oxide additions on the microstructure and mechanical strength of cement. Carbon N. Y. 95, 1083–1084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2015.08.089 (2015).

Mohammed, A., Sanjayan, J. G., Duan, W. H. & Nazari, A. Graphene oxide impact on hardened cement expressed in enhanced freeze–thaw resistance. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)mt.1943-5533.0001586 (2016).

Pratap, B., Mondal, S. & Rao, B. H. Prediction of compressive strength of bauxite residue-based geopolymer mortar as pavement composite materials: An integrated ANN and RSM approach. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 25, 597–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-023-00797-w (2024).

Abdulkadir, I., Mohammed, B. S., Ali, M. O. A. & Liew, M. S. Effects of graphene oxide and crumb rubber on the fresh properties of self-compacting engineered cementitious composite using response surface methodology. Materials (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15072519 (2022).

BS EN 12390-3. Testing Harden Concrete. Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. (BSI, 2009).

Japan Society of Civil Engineers. Recommendations for Design and Construction of High Performance Fiber Reinforced Cement Composites with Multiple Fine Cracks (HPFRCC), Concrete Engineering Series. Testing Method. Vol. 82. 6–10 (2008).

BSI, BS EN 12390-5: 2000. Testing Hardened Concrete. Flexural Strength of Test Specimens. (Br. Stand. Inst., 2000).

ASTM C469. Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. 1–5 (ASTM Stand. B. 04, 2002).

Bheel, N. & Mohammed, B. S. Modelling and optimization of long-term modulus of elasticity and Poisson’s ratio of graphene oxide based engineered cementitious composites by using response surface methodology. Diam. Relat. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2024.110949 (2024).

ASTM, A. C157/C157M-08: Standard Test Method for Length Change of Hardened Hydraulic-Cement Mortar and Concrete. (Annu. B. ASTM Stand., ASTM International, 2008).

Abdulkadir, I., Mohammed, B.S., Liew, M.S. & Wahab, M.M.A. Modelling and optimization of the impact resistance of graphene oxide modified crumb rubber-ECC using response surface methodology. In IOP Conference Series on Material Science Engineering. 012043. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/1197/1/012043 (2021).

Abdulkadir, I., Mohammed, B. S., Liew, M. S. & Wahab, M. M. A. Modelling and optimization of the mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composite containing crumb rubber pretreated with graphene oxide using response surface methodology. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125259 (2021).

Shamsaei, E. et al. Graphene-based nanosheets for stronger and more durable concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 183, 642–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.06.201 (2018).

Young, R. J. et al. The mechanics of reinforcement of polymers by graphene nanoplatelets. Compos. Sci. Technol. 154, 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2017.11.007 (2018).

Zhao, L. et al. An intensive review on the role of graphene oxide in cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117939 (2020).

Kang, D., Seo, K. S., Lee, H. Y. & Chung, W. Experimental study on mechanical strength of GO-cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 131, 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.11.083 (2017).

Devi, S. C. & Khan, R. A. Compressive strength and durability behavior of graphene oxide reinforced concrete composites containing recycled concrete aggregate. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101800 (2020).

Bheel, N., Ali, M. O. A., Kırgız, M. S., Shafiq, N. & Gobinath, R. Effect of graphene oxide particle as nanomaterial in the production of engineered cementitious composites including superplasticizer, fly ash, and polyvinyl alcohol fiber. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.03.010 (2023).

Bheel, N., Mohammed, B. S., Abdulkadir, I., Liew, M. S. & Zawawi, N. A. W. A. Effects of graphene oxide on the properties of engineered cementitious composites: Multi-objective optimization technique using RSM. Buildings https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13082018 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Dispersion of graphene oxide agglomerates in cement paste and its effects on electrical resistivity and flexural strength. Cem. Concr. Compos. 92, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2018.06.008 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Effects of graphene oxide agglomerates on workability, hydration, microstructure and compressive strength of cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 145, 402–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.04.058 (2017).

Mohammed, B. S., Achara, B. E., Nuruddin, M. F., Yaw, M. & Zulkefli, M. Z. Properties of nano-silica-modified self-compacting engineered cementitious composites. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 1225–1238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.137 (2017).

Khed, V. C., Mohammed, B. S., Liew, M. S. & Abdullah Zawawi, N. A. W. Development of response surface models for self-compacting hybrid fibre reinforced rubberized cementitious composite. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117191 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Yuvaraj, A., Di, J. & Qian, S. Matrix design of light weight, high strength, high ductility ECC. Constr. Build. Mater. 210, 188–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.159 (2019).

Zhang, Z. & Zhang, Q. Matrix tailoring of engineered cementitious composites (ECC) with non-oil-coated, low tensile strength PVA fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 161, 420–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.11.072 (2018).

Zhang, J., Gong, C., Guo, Z. & Zhang, M. Engineered cementitious composite with characteristic of low drying shrinkage. Cem. Concr. Res. 39, 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2008.11.012 (2009).

Li, G. & Zhang, L. W. Microstructure and phase transformation of graphene-cement composites under high temperature. Compos. Part B Eng. 166, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.11.127 (2019).

Abdulkadir, I. & Mohammed, B.S. RSM analysis and study on the 6 months compressive strength development and shrinkage behaviour of high volume fly ash rubberized ECC ( HVFA-RECC ). Int. J. Adv. Res. Eng. Technol. 11, 965–980 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3711364%0Ahttps://www.academia.edu/download/66200417/IJARET_11_09_095.pdf (2020).

Bheel, N. et al. A comprehensive study on the impact of nano-silica and ground granulated blast furnace slag on high strength concrete characteristics: RSM modeling and optimization. Structures https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106160 (2024).

Abdullah, G. M. S. et al. Effect of titanium dioxide as nanomaterials on mechanical and durability properties of rubberised concrete by applying RSM modelling and optimizations. Front. Mater. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2024.1357094 (2024).

Bheel, N., Mohammed, B. S., Liew, M. S. & Zawawi, N. A. W. A. Effect of graphene oxide as a nanomaterial on the durability behaviors of engineered cementitious composites by applying RSM modelling and optimization. Buildings. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13082026 (2023).

Bheel, N., Mohammed, B. S., Liew, M. S. & Zawawi, N. A. W. A. Durability behaviours of engineered cementitious composites blended with carbon nanotubes against sulphate and acid attacks by applying RSM modelling and optimization. Buildings https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13082032 (2023).

Bheel, N. et al. Effect of calcined clay and marble dust powder as cementitious material on the mechanical properties and embodied carbon of high strength concrete by using RSM-based modelling. Heliyon. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15029 (2023).

Bheel, N. et al. Utilization of millet husk ash as a supplementary cementitious material in eco-friendly concrete: RSM modelling and optimization. Structures. 49, 826–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.02.015 (2023).

Bheel, N., Mohammed, B. S., Mohamad, H., Sutanto, M. H. & Tafsirojjaman, T. Synergetic effect of multiwalled carbon nanotubes on mechanical and deformation properties of engineered cementitious composites: RSM modelling and optimization. Diam. Relat. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2024.111299 (2024).

Bheel, N., Chohan, I. M., Alwetaishi, M., Waheeb, S. A. & Alkhattabi, L. Sustainability assessment and mechanical characteristics of high strength concrete blended with marble dust powder and wheat straw ash as cementitious materials by using RSM modelling. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2024.101606 (2024).

Chohan, I. M. et al. Effect of seawater salinity, pH, and temperature on external corrosion behavior and microhardness of offshore oil and gas pipeline: RSM modelling and optimization. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67463-2 (2024).

Bheel, N. et al. A comprehensive study on the impact of human hair fiber and millet husk ash on concrete properties: Response surface modeling and optimization. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63050-7 (2024).

Gunst, R. F., Myers, R. H. & Montgomery, D. C. Response surface methodology: Process and product optimization using designed experiments. Technometrics. 38, 285. https://doi.org/10.2307/1270613 (1996).

Hong, D. L. H. et al. Deformation properties of rubberized ecc incorporating nano graphene using response surface methodology. Materials (Basel) 13, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13122831 (2020).

Adamu, M., Trabanpruek, P., Jongvivatsakul, P., Likitlersuang, S. & Iwanami, M. Mechanical performance and optimization of high-volume fly ash concrete containing plastic wastes and graphene nanoplatelets using response surface methodology. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125085 (2021).

Ryan, T. P. Design and analysis of experiments. Mod. Eng. Stat. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470128442.ch12 (2007).

Ba, D. & Boyaci, I. H. Modeling and optimization I: Usability of response surface methodology. J. Food Eng. 78, 836–845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.11.024 (2007).

Adamu, M., Haruna, S. I., Ibrahim, Y. E. & Alanazi, H. Evaluation of the mechanical performance of concrete containing calcium carbide residue and nano silica using response surface methodology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-20546-x (2022).

Bheel, N., Mohammed, B. S., Ali, M. O. A., Shafiq, N. & Radu, D. Effect of graphene oxide as a nanomaterial on the bond behaviour of engineered cementitious composites by applying RSM modelling and optimization. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 26, 1484–1507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.07.278 (2023).

Divya, S. & Praveenkumar, S. An integrated evaluation of graphene-based concrete mixture with copper slag and quarry dust using response surface methodology. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.108876 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number: TU-DSPP-2024-173.

Funding

This Research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, Project No. (TU-DSPP-2024-173).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sandeep Kumar: Conceptualizations; design the experiments, materials, analysis tools or data. Naraindas Bheel: Conceptualizations; design the experiments; analyzed and interpreted the data; wrote the original paper. Shahnawaz Zardari: Data curation; analyzed and interpreted the data. Ahmed Saleh Alraeeini: Conceptualizations; formal analysis; analyzed and interpreted the data; designed the experiments; writing the original paper. Abdulrazak H. Almaliki: Conceptualizations; Funding Acquisition; formal analysis; Writing-reviewing and Editing. Omrane Benjeddou: analyzed and interpreted the data; writing and reviewing the original manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, S., Bheel, N., Zardari, S. et al. Effect of graphene oxide on mechanical, deformation and drying shrinkage properties of concrete reinforced with fly ash as cementitious material by using RSM modelling. Sci Rep 14, 18675 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69601-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69601-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effect of seawater salinity and temperature on material performance and marine ecotoxicity of offshore pipeline using RSM modelling

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2026)

-

Optimizing nanomaterial dosages in concrete for structural applications using experimental design techniques

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Synergistic effects of fly ash, ground granulated blast furnace slag, and graphene oxide in low-carbon concrete: modelling, optimization, and sustainability assessment

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Optimization of durability characteristics of engineered cementitious composites combined with titanium dioxide as a nanomaterial applying RSM modelling

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Evaluation of the mechanical characteristics of bagasse ash concrete using response surface methodology

Discover Sustainability (2025)