Abstract

Polygonatum kingianum Collett & Hemsl., is one of the most important traditional Chinese medicines in China. The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between herb quality and microbial-soil variables, while also examining the composition and structure of the rhizosphere microbial community in Polygonatum kingianum, the ultimate goal is to provide a scientific approach to enhancing the quality of P. kingianum. Illumina NovaSeq technology unlocks comprehensive genetic variation and biological functionality through high-throughput sequencing. And in this study it was used to analyze the rhizosphere microbial communities in the soils of five P. kingianum planting areas. Conventional techniques were used to measure the organic elements, pH, and organic matter content. The active ingredient content of P. kingianum was identified by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Colorimetry. A total of 12,715 bacterial and 5487 fungal Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU) were obtained and taxonomically categorized into 81 and 7 different phyla. Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Acidobacteriae were the dominant bacterial phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota were the dominat fungal phyla. The key predictors for bacterial community structure included hydrolysable nitrogen and available potassium, while for altering fungal community structure, soil organic carbon content (OCC), total nitrogen content (TNC), and total potassium content (TPOC) were the main influencing factors. Bryobacter and Candidatus Solibacter may indirectly increase the polysaccharide content of P. kingianum, and can be developed as potential Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR). This study has confirmed the differences in the soil and microorganisms of different origins of P. kingianum, and their close association with its active ingredients. And it also broadens the idea of studying the link between plants and microorganisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A perennial herb in the Liliaceae family, Polygonatum kingianum Collett & Hemsl., is one of the most important traditional Chinese medicines in China. P. kingianum also is an important industrial crop in Southwest China with a high economic value. Chinese medical classics like Mingyi Bielu (456–536 AD, Han Dynasty) and Xinxiu Bencao (659 AD, Tang Dynasty) mention that it has the ability to extend life without toxicity1. Therefore, people consider it a “top-class” herb and have studied its chemical composition and pharmacological activity in depth. According to recent studies, P. kingianum contains Polygonatum polysaccharide, Steroidal saponins, and flavonoids2,3 which possess hypoglycemic, antioxidant, antitumor, and anti-inflammatory properties. There are over 150 kinds of modern traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) compounds and 170 kinds of health care products made from P. kingianum as the main raw material, such as HuangJing ZanYu Capsules, Huangjing Yangyin Syrup, Eleven Flavor Huangjing Granules (https://db.yaozh.com/zhongyaocai). In 2020, the planting area for this herb reached 101,000 mu, resulting in an output value of 660 million yuan (Department of Agricultural Rurality, Yunnan, China). The economic benefits of this plant are directly related to its quality. However, the quality of P. kingianum plants is currently uncontrollable, resulting in uneven quality. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a safe and effective method to enhance the quality of P. kingianum.

The rhizosphere is the narrow region of soil belt that is connected to the plants and affected by root exudates. Soil microorganisms in the rhizosphere are essential for enhancing soil nutrient availability and regulating soil fertility, which also plays a key role in promoting plant health4. Certain types of bacteria, such as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), have the capability to produce auxin analoguesthat stimulate plant growth5. Active bacteria in the soil can also greatly improve the enrichment of nutrient elements in the soil6. Bacterial genera such as Genera, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, Acinetobacter, Burkholderia, Arthrobacter, and Paenibacillus are considered as PGPR which helps in agricultural production7,8,9. Similarly, the secretions produced by the plant roots create an environment conducive to bacteria survival in the rhizosphere, thus affecting the bacterial growth in soil10,11. The complementary relationship between plant roots, microorganisms, and soil is evident and understanding the specific internal relations between them will helps us compered the factors influencing plant growth.

The research direction on P. kingianum cultivation has always focused on light, water, undergrowth cultivation, etc., but little is known about nutrient levels, pH values, organic elements, etc., that may affect soil quality12,13. As a result, there is a certain relationship between the quality of P. kingianum, the physical and chemical properties of soil samples, and its rhizosphere microbial community. To explore this relationship, we collected rhizosphere soil and root samples from five different P. kingianum growing regions in Yunnan Province, China. Using Illumina NovaSeq technology, we studied the variation, diversity, and abundance of rhizosphere soil microbial communities, determined the content of organic elements pH, organic matter, and main active components in the soil, and investigated the correlation between the physical and chemical properties of the soil and bioactive components. The study findings will help to understand the rhizosphere microbial diversity and provide theoretical references for improving the quality of cultivated P. kingianum.

Materials and methods

Collection of samples

The samples were collected in Yunnan Province, China, which is the main production area of P. kingianum (Fig. 1) in October 2021, mainly in Wase Township (WS), Yongping County, Longmen Township (YP), Gucheng Township (DL), Dali City, Zijin Township (ZJ), Weishan County, and Hongyan Township (MD), Maidu County. The soil attached to the rhizomes of P. kingianum (5 years old) was collected (Table 1).The rhizomes were gently shaken to remove the bulk soil, and the soil remaining on the rhizomes surface were considered the rhizosphere. The rhizosphere was placed in sterile 0.9% NaCl for 5 min with moderate agitation, and then the precipitated soil was collected and preserved at − 80 °C14. P. kingianum roots were washed with tap water and used to detect the content of chemical components’ content.

Rhizosphere microbiome analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the samples using the CTAB method. The DNA purity and concentration were evaluated by gel electrophoresis15. Appropriate samples were taken in centrifuge tubes and diluted to 1 ng/µL with sterile water16. The V4 region of bacterial 16S rRNA was PCR amplified using primers 515f-806r, while the fungal ITS fragment was amplified using primers ITS1 (Its5-1737f, ITS2-2043r) and ITS2 (ITS3-2024f, ITS4-2409r). (The amplification program included predenaturation at 98 °C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles at 98 °C for 10s, 50 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min). The bacterial 16S rRNA genes of the V4 regions were amplified by specific primers (515F-806R). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction solution consisted of 15 μL 2× Phusion Master Mix (Phusion® High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix with GC Buffer New England Biolabs), 3 μL primer (2 µM/μL), 10 μL DNA (1 ng/μL), and 2 μL of double distilled (dd) H2O. The reaction took place in Bio-rad T100 instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratory, CA, USA) with a thermocycling program of 1 min at 94 °C for predenaturation, 30 cycles of 10 s denaturation at 98 °C, 30 s annealing at 52 °C, 30 s extension at 72 °C, Gelelectrophoresis (2% Agarose) was used to determine the lengths and concentrations of the PCR products. According to the product concentration, equal concentrations of the mixes were taken. Subsequently, the PCR product mixture was purified using the GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA), resulting in bands of 400 –450 bp. The DNA libraries were then prepared using the TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, CA, USA). The library’s quality of the library was assessed using the Qubit@ 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific) and the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. Finally, the library was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina Company, CA, USA), generating 250 bp paired-end reads. There was 97% similarity was observed in the clustered operational taxonomic units (OTU). Taxonomic data annotation of bacteria and fungi sequences was conduted using the SILVA (https://www.arb-silva.de/) and UNITE (version 8.0, https://unite.ut.ee) databases.

Soil physicochemical properties analysis

The extracted soil’s pH with deionized water (soil:deionized water = 1:5) was measured using a pH meter. The dichromate oxidation method17 was used to measure the organic carbon content (OCC). The total nitrogen content (TNC) was measured using the Kjeldahl method. The total phosphorus content (TPHC) and total potassium content (TPOC) content were measured using the molybdenum antimony anti-colorimetric and flame photometric methods after the perchloric acid sulfuric acid method. The alkaline hydrolysis method measured the hydrolysable nitrogen content (HNC). Sodium bicarbonate extraction and the molybdenum antimony anti-colorimetric method measured the available phosphorus content (APHC). The available potassium content (APOC) was measured by the ammonium acetate exchange-flame photometry18.

Ingredients analysis

Chemicals and reagents

Ginsenoside Rb1 (MUST-2111512), ginsenoside Rc (MUST-21111511), dioscin (17071104), liquiritigenin (MUST-21091602), rutinum (MUST-22022507), quercetin (SYVX-RS2M), and pseudoginsenoside F11 (MUST-21051408) (purity > 98%) were purchased from the Chengdu Must Bio-technology Co., Ltd (Chengdu, China). Acetonitrile and ammonium acetate were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany, 20171013). Analytical-grade chemicals and solvents were also utilized.

Instrumentation and chromatographic conditions

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was conducted using an Agilent 1260 Infinity system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The HPLC column utilized was a Phenomenex Gemini NX-C18 (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm, Phenomenex, MA, USA). The analysis was carried out with a mobile gradient phase of water (A) and acetonitrile (B) at 30 °C. A linear gradient was applied as follows: 0–5 min (95–90%, A), 5–12 min (90–79%, A), 12–15 min (79–75%, A), 15–19 min (75–75%, A), 19–29 min (75–57%, A), 29–40 min (57–0%, A), and 40–45 min (0–0%, A). The flow rate was 1 mL∙min−1, the DAD detector was set at 200 nm, and the sample injection volume was 20 μL.

Preparation of sample solution

The P. kingianum samples before use were dried at 50 °C for 12 h to reach a constant weight. Each dried sample was ground to a fine powder (0.84 mm) using a pulverizer. An accurately weighed sample of 1 g powder sample was placed inside the stoppered Erlenmeyer flasks. Approximately 80% ethanol was added to achieve a 1:20 ration. Ultrasonic extraction was conducted at 60 °C for 50 min. The filtrate was then filtered, distilled, and dried by adding the 20 ml of distilled water, extracting twice with 20 ml of n-butanol, (20 ml, 20 ml) taking the n-butanol layer, spin-drying it, and adding a small amount of methanol in a 10 ml volumetric flask. Finally, a 0.45 μM Millipore filter membrane was used to filtrate the filtrate for the trial.

Statistical analysis

The experiments were repeated in triplicates. Alpha diversity was estimated using Qiime software (Version 1.9.1)19, including Chao1, Simpson, and Shannon indices20, and tested using Kruskal–Wallis analysis. The differences in were observed and analyzed by the Analysis of Similarity (ANOSIM) function of the vegan package in R version 4.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). ANOSIM was employed to analyze the differences between microbial communities. For bacteria and fungi, Bray–Curtis, Weighted UniFrac (WU), and Unweighted UniFracto (UU) distance matrices were employed. The relative abundance of the different taxa was plotted using heat maps. Additionally, LEfSe was utilized to detect biomarkers in the microbial communities. The correlation between microbial communities and environmental elements was studied using the Mantel test and redundancy analysis (RDA). The figures were plotted generated using ggplot2 and the vegan package. The relationship between dominant rhizosphere microorganisms, soil physicochemical properties, and major active constituents of P. kingianum21,22 was determined through Spearman correlation analysis using SPSS software. Significant correlations between Bray–Curtis community heterogeneity, environmental factors, and geographical distance were identified using the Mantel test. Distance–decay relationships (DDR) for community similarity were compared using covariance analysis and visualized with the ggplot2 package. The SparCC algorithm calculated the correlations between Operationl Taxonomic Units (OTUs) for different locations. Based on the significant correlations (absolute correlation values > 0.6 and p-values < 0.05) co-occurrence networks of bacteria and fungi were constructed that existed between the two pairs.

Results

Microorganisms diversity and structure analysis of the rhizosphere soil

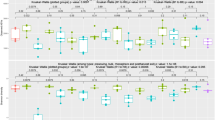

Microbial communities’ alpha diversity (Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson) was calculated for soil samples from different areas (Fig. 2). The results of soil samples taken from various locations did not significantly differ according to the chao1 and Simpson indices of bacterial communities (p > 0.05), while the Shannon index varied significantly (p < 0.05) depending on the sample sites. The Simpson index was above 99%, while the Shannon indices all exceeded 10. This suggests that the bacterial species present in the soil in this region are abundant and more uniformly distributed, which is also evident by the Chao1 index. There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the three indices at the five sites in terms of fungal communities. The Shannon indices in descending order were MD, ZJ, WS, YP, and JD. However, the total number of species (Chao1) at JD was much greater than MD. Additionally, Bray–Curtis, WU, and UU distances analyses were used to visualize the Beta diversity at various sampling sites (Fig. 2). The study found that the microbial community composition and structure varied significantly among the five sampling sites, while all three samples from different sites showed good consistency. Figure 2 showed three sites, WS, ZJ, and YP, close to each other, while the other two sites, MD and JD, were far from the rest. ADONIS analysis revealed significant differences among different bacterial community samples (R2 = 0.81525, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.76485, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.79804, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.50369, p < 0.01, R2 = 7717, p < 0.01). The intergroup differences between MD, JD and ZJ, JD in the fungal community samples were extremely significant (R2 = 0.80127, p < 0.01, and R2 = 0.74887, p < 0.01).

Alpha and beta diversity of microbial communities. a-f: the alpha diversity index of Chao (a), Shannon (b), and Simpson (c) for the bacterial community; the alpha diversity index of Chao (d), Shannon (e), and Simpson (f) for the fungal community, different letters on the bars indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). g-l: the beta diversity of the bacterial community based on the Bray-Curtis (g), WU (i), and UU distances (h); the beta diversity of the fungal community based on the Bray-Curtis (j), WU (l), and UU distances (k).

Microbiological community composition

The rhizosphere soil samples collected from five different locations identified 1915 bacterial species. The maximum number of WS species was 1155 and the minimum number of MD species was 460. Around 81 bacterial phyla were identified. There were 12 phyla with relative abundance greater than 1% (Fig. 3), among which the phylum Proteobacteria was the dominant in most sample sites, with a relative abundance ranging from 22.3 to 43.7%. Acidobacteriae, (14.2% to 19.1%), Verrucomicrobiota (2% to 10.1%) and Actinobacteriota (1.7% to 8.2%) were the other relatively abundant phyla of bacteria. However, among the five sample sites, there were differences in the relative abundance of these soil bacterial phyla. The relative abundance of the phylum Proteobacteria, for instance, was consistently higher at the WS locus than that of JD, but the relative abundance of the phyla Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, and Verrucomicrobiota was lower than those of the other locales. Among them, ascomycota and basidiomycota were the most abundant fungal phyla, with a relative abundance around 75%. The abundance of ascomycota was greater than that of basidiomycota in most of the areas except WS and YP. Furthermore, 883 bacterial genera were identified in the studied soils. The top 30 most abundant genera are shown in the figure, and the dominant genera in these sample sites were similar, including Bradyrhizobium, Bryobacter, Candidatus_Udaeobacter, and Candidatus_Solibacter. For fungi, fusarium, and geminibasidium were dominant.

Identification of microbial biomarkers

We used LEfSe analysis to identify and compare P. kingianum biomarkers at each site based on the taxonomic composition of the rhizosphere microbial communities (Fig. 4). The aim was to explore the taxonomic characteristics of the rhizosphere soil microbial communities of P. kingianum across different sites. Ultimately, 46 discriminatory biomarkers with a logarithmic LDA score > 4.5 were found. The bacterial community identified 16 biomarkers in the ZJ, WS, and MD groups that belonged to diverse phylogenetic groups such as Verrucomicrobiae, Verrucomicrobiota, Candidatus_Udaeobacter, Chthoniobacterales, Chthoniobacteraceae, and in the JD, and YP groups, Acidobacteriae and Proteobacteria were identified, respectively. The LEfSe study revealed 30 biomarkersin the fungal community, spanning 7 genus, 6 families, 8 orders, and 7 phyla, and 2 phylum levels. Biomarkers at the phylum level were clustered in Basidiomycota and Ascomycota, indicating uniformity tin fungal communities across the five sites in terms of water composition. In the MD region, biomarkers were clustered at the order and family levels, while in the WS region, they were clustered in the Basidiomycota and its subordinate Agaricomycetes, Tremellomycetes, and Tremellomycetes. Tremellomycetes and the its subordinate Tremellales were also identified. Rhizosphere fungi biomarkers were found in the JD and MD regions, showing relative similarity among the five regions. Additionally, the WS, YP, and ZJ regions exhibited greater similarity, possibly due to shared soil climate and other factors.

The LEfSe identifies the significantly different (p < 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test, linear discriminant analysis values > 4.5) bacterial (a) and fungal (b) at multiple taxonomic levels in the five regions. Colored dots represent the taxa with significantly different abundances between sites, and from the center outward, they represent the kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, and genus levels.

®

Correlation analysis of soil physicochemical properties and microbial abundance

Table 2 presents the main physicochemical characteristics of the rhizosphere soils from the five sample sites. The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test indicated that soil physicochemical properties, including OCC, TNC, TPOC, APOC, and altitude, were accompanied by significant changes (p < 0.01) depending on the origin. The pH of the soil ranged from 6.5 to 7.5, with significant differences among sampling sites, indicating a neutral soil in the area. Additionally, the APOC content in the WS sample site was lower than the other loci and the pH value was the lowest among all samples. The APHC content had differences among the five sampling sites as YP > MD > WS > ZJ > JD, and the TNC in ZJ was higher than in the other sites. It is noteworthy that the TPHC did not differ extensively among the five sampling sites. The correlation analysis of species composition diversity of rhizosphere microorganisms with physicochemical properties by Mantel Test revealed a positive correlation between elevation and OCC, TNC, and TPOC in the rhizosphere soil. Soil TPOC and APOC contents had significant effects on microbial diversity, and soil OCC, TNC, and HNC contents affected the bacterial diversity. Based on bacterial diversity, soil OCC and TPOC contents were highly correlated with Actinobacteria and Verrucomicrobiota, and HNC contents with Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota. Soil physicochemical properties had little effect on fungal diversity, where TPOC, TNC, and OCC content were correlated with lomeromycota. Additionally, HNC was correlated with Aphelidiomycota, APOC with Ascomycota, and Zoopagomycota and elevation were negatively correlated with Ascomycota and Zoopagomycota. The response of the microbial community to environmental factors was analyzed via redundancy analysis (RDA) and Pearson correlation analysis. The RDA results showed that the first two axes contained 69.34% and 71.54% of the bacterial and fungal community composition, (Fig. 5); with RDA1 explaining most of it. Among the bacterial species, Bryobacter, Candidatus_Solibacter, and Sphingomonas were positively correlated with pH, altitude, OCC, and TPOC. Corynebacterium, Candidatus_Udaeobacter was positively correlated with TNC, MND1, and HNC. TPOC and APOC were positively correlated. Among fungal species, Fusarium was positively correlated with APOC, pH, TNC, and the RDA double point method.Further replacement tests showed that the soil’s HNC and APOC identified the bacterial community structure. Meanwhile, OCC, TNC, and TPOC of the soil changed the fungal community structure.

Analysis of the active components of P. kingianum

Table 3 presents the primary active components of P. kingianum from five sampling sites. The results indicate that the polysaccharide content of P. kingianum obtained from YP sampling site is the highest, followed by the WS sampling site. While there are variations in the content of the active components of Polygonatum sibiricum in different areas, the Kruskal–Wallis test results suggest that this variation is not extreme. The RDA and Pearson correlation analysis illustrated the relationship between the top 10 bacterial and fungal genera in abundance across different locations of P. kingianum and rhizosphere soils. The study found that the revealed that polysaccharide content was positively correlated with Mortierellomycota, saponin flavone ginsenoside. Additionally, the Rb1 content showed positive correlations with Proteobacteria, Ascomycota, Bacteroidota, and these correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

The correlation analysis between the main active components of P. kingianum and soil physicochemical properties (Fig. 6a) showed that TNC had a promoting effect on the accumulation of dioscin based on Spearman’s coefficient. The pH also had a promoting effect on the ginsenoside accumulation. Rb1, flavone, HNC, and APOC had a promoting effect on the accumulated active components of P. kingianum except for polysaccharides. However, OCC and TPOC had inhibitory effects on the accumulated components, except for polysaccharide flavone, and saponin.

Network analysis

The intricate relationship among microorganisms were delineated based on their topological characteristics (Table 4). In summary, the bacterial co-occurrence exhibited higher edges, density, and average degree in JD, ZJ, YP, and MD, indicating more complex topologies compared to the fungal networks. However, these characteristics were not observed in WS (Fig. 7). The bacterial network primarily consisted of members from Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, and Verrucomicrobiota, aligning with community composition results. In the ZJ region, the edges, density, and average degree of the bacterial co-occurrence network in ZJ region were significantly higher than in other regions. YP and MD also showed higher values for edges, density, and average degree compared to other regions. The negative correlations between the co-occurrence networks of YP, MD, and ZJ were lower than in other regions, suggesting reduced competition among bacterial species in these two locations.

The co-occurrence network interactions of soil bacteria (a) and fungi (b). Nodes represent OTU, whereas a connection indicates a strong (r > 0.6) and significant positive (p < 0.05) correlation. The color of the nodes indicated the phylum, the size of each node was proportional to the number of connections (i.e., degree); the thickness of each connection between two nodes (i.e., edge) was proportional to the correlation coefficient (red indicates a positive correlation and gray indicates negative correlation).

The co-occurrence network of fungi was dominated by Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, which accounted for more than 50% of the total. The co-occurrence network of MD and ZJ contained mostly Basidiomycota nodes, aligning with the community composition findings. The edges, density, and average of the fungal co-occurrence network in WS were significantly higher than in other regions. This region also had very few negative correlations, which may explain the highest microbial diversity.

Distance decay of microbial communities

The change community similarity with increasing geographical distance was characterized by DDR. The results revealed that bacterial and fungal community similarity gradually decreased with increasing geographic distance (Fig. 8). Fungal communities (R2 = 0.162) exhibited a faster rate of community similarity reduction than the bacterial communities (R2 = 0.1312). The geographic differences had a greater impact on microbial communities than the environmental differences. The Mantel test indicated that fungal community changes were significantly correlated with the geographic distance factor (r = 0.334, p = 0.026) rather than with the environmental factors (r = 0.174, p = 0.071). This suggests that geographical distance is more important than environmental factors within the range of 2–102 km (Table 5).

Discussion

The rhizosphere soil is composed of a complex, dynamic biological environment. A good root environment is important for maintaining the rhizosphere stability and promoting the healthy development of the surrounding plants22. According to previous studies, rhizosphere microorganisms can coexist with the plant roots, colonize, and maintain tgem. They play an important role in promoting the growth and development of plants23. These microorganisms can use the plant root exudates to trigger feedback mechanisms that to promote plant growth24, improve theenvironment25, or treat certain diseases26. Therefore, understanding the microbial community structure, nutrient elements, physical and chemical properties and other micro-environmental factors of the rhizosphere, and extracting soil environmental information, can help develop ways to promote growth of the medicinal plants growth and enhance drug efficacy.

Relationship between bacterial community in the rhizosphere and environmental factors

As discussed, the rhizosphere microbial community structure of P. kingianum was varied across different soil regions, as revealed from α and β diversity analysis. In this study, Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriae, Actinobacteriota, and Verrucomicrobiota were identified as the most abundant taxa biomarkers on account of the rhizosphere bacterial community of P. kingianum. However, previous studies have indicated that the predominant rhizosphere microorganisms of watermelon27, grape28, barley29, Dendrobium nobile30, and Citrus reticulata31 plants are primarily found in Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, and Bacteroidetes. The presence of different dominant phyla in the rhizosphere of P. kingianum may be attributed to the unique root secretions and the specific location of the drug application site underground. This also demonstrates that the rhizosphere microorganisms vary among different plants differ under diverse soil conditions, influenced by factors such as drought, salinity, and fertility. Among the dominant phyla, Proteobacteria are considered to be the r-strategists, thriving under high nutrient conditions. Their increased abundance often indicates changes in the soil’s nutrient composition and plays a crucial role in carbon and nitrogen cycling in the soil32. This aligns with the findings of this study, which show a positive correlation between Proteobacteria and the HNC amount in the soil. Actinobacteriota, another dominant phylum, play a role in the global carbon cycle14 and the decomposition of soil organic matter33 decomposition. Actinobacteria, are also unutilized as biocontrol agents to manage plant diseases transmitted through soil and seeds34. Ascomycota and Basidiomycota are the most prevalent fungal phyla, with Ascomycota exhibiting rapid growth and contributing to soil nutrient cycling, promoting eutrophication in the natural environments35. The abundance of Ascomycota reflects the nutrient level in the soil.

RDA/CCA analysis mapped the influencing factors that contributed to the change in microbial community composition. It was found that microbial communities in each of the five regions were associated with different biological and spatial variables, suggesting that different P. kingianum cultivation regions have significantly different biogeographic patterns. Mantel test further showed significant correlation between bacterial and fungal community associations in different locations and various soil properties to be significantly correlated. Proteobacteria and Actinobacteriota were found to exhibit higher metabolic activity in soils contaminated with heavy metals, aligns with is similar to our findings that Actinobacteriota and Verrucomicrobiota were more abundant in soils with higher organic carbon content (OCC), total particulate organic carbon (TOPC), and total nitrogen content(TNC). Furthermore, our results revealed that altitude was negatively correlated with the phylum Aspergillus and positively correlated with the Actinobacteriota, Acidobacteria, and Verrucomicrobiota. This finding contradicts that of Lazzaro et al., who revealed that high-altitude soil microorganisms are usually dominated by the phylum Aspergillus36. We speculate that this difference it may be due to seasonal and climatic variations, as high-altitude soil microorganisms are typically influenced by factors such as like altitude, climate, and temperature. Weak correlations were found between Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota and HNC, but HNC was identified as the most efficient form of nitrogen (N) in the soil, directly absorbable by plants37,38. It strongly correlates with rhizosphere microorganisms. Further exploration is necessary to gain deeper understanding of their relationships.

At the genus level, Candidatus_Udaeobacter is the most abundant among the five sample sites. Recent and recent reports have revealed it as an anaerobic heterotrophic microorganism that can utilize limited carbon sources like glucose, pyruvate, and chitosan. It metabolizes polysaccharides, individual amino acids, and vitamins, and shows deficiencies in several amino acids and vitamins39. This indicates the dependency of it on the external environment for survival. Coincidentally, the RDA analysis results showed that its abundance was positively correlated with the organic matter content in the soil, which could be one of the potential relationships between soil physicochemical properties and microbial abundance. The abundance of Fusarium among fungi was significantly correlated with the amount of APOC in the soil (Fig. 5). However, Fusarium causes pathogenicity in a large number of plants, such as cucumber40, wheat41 and cotton42. The occurrence of soil-borne diseases can be reduced by decreasing the application of phosphorus fertilizer. It was found that rhizosphere microorganisms are actively involved in root–soil interactions, and plant roots are capable of attracting or recruiting specific microorganisms into the rhizosphere by deposition secondary metabolites, thus shaping the rhizosphere microbiome’s composition and structure.

Analysis of co-occurrence networks and biogeographic patterns of rhizosphere microorganisms

The results show that bacterial and fungal co-occurrence networks differ in various regions, aiding in our understanding of which helps us understand the potential interactions within a typical ecological niche space43. We observed that the network of bacteria that co-occur in the MD rhizosphere had more positive correlations, indicating that the bacterial communities in this region collaborate and may help plants resist resistance external stresses44. The rhizosphere microbial network also revealed connections among taxa, exposing potential ecological niches and highlighting key species among them45,46. The modularity values of the rhizosphere fungal network were higher than those of the rhizosphere bacterial network, suggesting stronger ecological niche differentiation and implying greater stability of the rhizosphere fungi44. It was discovered that species can uphold maintain microbial ecological network stability and support soil function47,48. The key species among the rhizosphere bacteria of P. kingianum in our study were Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, and Verrucomicrobiota, while the key species among the rhizosphere fungi were Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, which was consistent with the findings of abundance analysis findings. A higher number of key species indicates a more stable network in soil microbial communities49. The microbial network in our study had relatively more WS nodes, suggesting a more stable network, which a correlation to the modularity value. However, microbial networks are influenced by multiple parameters, and the current parameters are insufficient not sufficient for precise prediction, necessitating further series of experiments for validation44.

The DDR analysis revealed significantly different distance decay relationships in the rhizosphere microbial communities of P. kingianum with significantly different distance decay relationships (Fig. 7), possibly attributed to distinct habitats and diffusion limitations50,51. We assessed various spatially relevant environmental variables, including temperature, altitude, precipitation, etc., to elucidate the impact of describe the distance effect on microbial communities52. The Mantel test indicated that both spatial distance and environmental factors influence the distribution of rhizosphere microbial communities, with the spatial factors having a stronger impact. Particularly, rhizosphere fungal communities exhibit significant differences, with increasing spatial distance, a finding consistent with Zhao et al.32. The distribution and abundance of microbial communities are influenced controlled by distance and environmental variables53,54, leading to variations in the composition and structure differences of microbial communities across different regions. Specific plant-associated microbiota in medicinal plants and their rhizosphere have been reported to produce unique bioactive secondary metabolites. Harnessing these specific rhizosphere microorganisms can potentially impact and enhance the quality of medicinal plants55. Strategic manipulation of microbial communities can aid in the biological management of P. kingianum cultivation and serve as foundation for enhancing the productivity of herbal medicines.

Analysis of relevant factors affecting the quality of P. kingianum

Several studies have reported the role of PGPR in promoting the accumulation of plant active ingredients56. After inoculation with PGRP (B. polymixa, Pseudomonas putida, and Azotobacter chroococ) the active ingredient stevioside of Stevia rebaudiana is increased57. Exiguobacterium oxidotolerans and B. pumilus can increase the main chemical constituent of Bacopa monnieri, bacoside-A58. Several studies have shown that the composition and abundance of inter-root microbial communities may play a crucial role in influencing healthy plant growth and ecological functions. For instance, microorganisms are involved in various physiological processes of the host plant Ruppia sinensis. The surrounding environment serves as a vibrant microbial resource site for host microorganisms. Seagrass sediments and the diversity of bacterial communities in the inter-root contain more nutrients than the surrounding seawater, which can protect microbial growth while providing nutrients to the host plant59. Ubiquitous actinomycetes, a group of G+C Gram-positive bacteria characterized by filamentous morphology, are widely distributed in soil and water bodies. They play a vital role in the decomposition of organic matter and carbon cycling. Their presence as a significant component of inter-root microorganisms positively impacts plant growth and soil health through the production of bioactives and enzymes60. The abundance of denitrifying bacteria (e.g., Steroidobacteraceae) decreased, while the abundance of denitrification-associated bacteria (e.g., Geobacter, Anaeromyxobacter, and Ignavibacterium) increased, contributing to enhanced nitrogen effectiveness. Furthermore, the combined treatment of tufted mycorrhizal fungi and biochar promoted plant root growth, resulting in changes in soil microbial structure61. This led to an increase in the abundance of nitrogen-cycling genes, consequently enhancing nitrogen uptake by maize roots and stems62. Although some studies have conducted the preliminary analyses of the rhizosphere microbial community of P. kingianum, no in-depth studies have been conducted on rhizosphere bacteria affecting the active ingredient content, and their effect on the quality of P. kingianum is still not clear63. This study compared the active ingredient contents of P. kingianum from five P. kingianum cultivation areas in southwest China and explored the soil and biological factors that might affect the effect on the quality of P. kingianum. Bradyrhizobium, Sphingomonas and Bryobacterium accounted for a relatively high proportion of the dominant bacterial genera in the rhizosphere. They are considered PGPRs and are widely found in rhizosphere plant soils. Due to their strong environmental adaptability and PGP characteristics, such as nitrogen fixation, resistance to salt stress and resistance to pathogenic bacteria, it is widely used in agricultural production64,65. Thus, these dominant genera may have a significant impact on the growth and accumulation of active ingredients in P. kingianum. However, the environment in which the existence of rhizosphere bacteria exist is complex, and bacteria are not the only factors that affect the content of active substances in medicinal plants. Soil factors play an important role in the soil environment affecting the structure of bacterial diversity, and the quality of medicinal plants66,67. The correlation between soil factors and bacterial genera, and active ingredients in rhizosphere soils was expressed in this study through correlation and redundancy analysis. Soil pH, OCC, APHC, and TPHC were positively correlated with polysaccharide and saponin contents in the rhizomes of P. kingianum. Among the responsive bacteria, Dongia, Bryobacter, Gaiella, Ellin6067, Candidatus Solibacter, and MND1, which play important roles in the accumulation of polysaccharides, flavonoids and saponins, were classified as Chloroflexi. Among them, Candidatus, can decompose organic matter and utilize carbon sources52, which is positively correlated with soil organic matter content, and Bryobacter was significantly enriched in healthy plants. These genera showed a positive correlation with pH and OCC and had a significant impact on sugar accumulation. The biological activity of microorganisms could provide substrates for polysaccharide synthesis in A. flavus, promoting the accumulation of polysaccharides and total sugars in rhizomes. These bacteria, through nutrient uptake, could increase the nutrient content in the plant, which could explain how polysaccharides accumulate in the rhizomes of P. kingianum. The study found that high pH and OCC create a suitable environment for bacterial growth (Fig. 6), resulting in an increase in indirect polysaccharide content in P. kingianum’s rhizomes. Differences in rhizosphere bacteria and soil factors were observed in different regions, and understanding their potential relationships may help identify key factors affecting herb quality.

Conclusion

The findings examine the rhizosphere soil’s physical and chemical properties of the rhizosphere soil, as well as its diversity, composition, and key species. They provide new insights to deepen our understanding of the rhizosphere’s ecological role in the environment. The findings revealed that Proteobacteria, Acidobacterium, Actinobacteria, and Warts were discovered as highly abundant taxa in all soil samples and played a crucial role in soil health, nitrogen cycling, and disease control. According to the results of our experiments, the OCC is believed to have a significant impact on the abundance and diversity of both fungal and bacterial communities. The increase in polysaccharide content in P. kingianum may be attributed to the bacterial species Bryobacter and Candidatus Solibacter, both of which have the potential to be developed into PGRP. This study enhanced our understanding comprehension of the factors influencing soil quality and proposed a theoretical framework and potential production method for its cultivation.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data are accessible at the NCBI-SRA under the accession number PRJNA909426.

References

Xu, Y. L., Wang, Y. Z., Yang, M. Q. & Zhang, J. Y. Textual research on Polygonati rhizoma and ethnic usage. Chin. J. Exp. Trad. Med. Formulae 27, 237–250 (2021).

Li, X. C. et al. Steroid saponins from Polygonatum kingianum. Phytochemistry 31, 3559–3563 (1992).

Wang, Y. F., Lu, C. H., Lai, G. F., Cao, J. X. & Luo, S. D. A new indolizinone from Polygonatum kingianum. Planta Med. 69, 1066–1068 (2003).

Baudoin, E., Benizri, E. & Guckert, A. Impact of artificial root exudates on the bacterial community structure in bulk soil and maize rhizosphere. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35, 1183–1192 (2003).

Vessey, J. K. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria as biofertilizers. Plant Soil 255, 571–586 (2003).

Mendes, L. W., Kuramae, E. E., Navarrete, A. A., Veen, J. A. & Tsai, S. M. Taxonomical and functional microbial community selection in soybean rhizosphere. ISME J. 8, 1577–1587 (2014).

Shang, J. & Liu, B. Application of a microbial consortium improves the growth of Camellia sinensis and influences the indigenous rhizosphere bacterial communities. J. Appl. Microbiol. 130, 2029 (2020).

Wang, L., Li, Z. Y., Liu, R. R., Li, L. L. & Wang, W. W. Bacterial diversity in soybean rhizosphere soil at seedling and mature stages. Pol. J. Microbiol. 68, 281–284 (2019).

Zi, H. Y., Jiang, Y. L., Cheng, X. M., Li, W. T. & Huang, X. X. Change of rhizospheric bacterial community of the ancient wild tea along elevational gradients in Ailao mountain, China. Sci. Rep. 10, 9203 (2020).

Bais, H. P., Prithiviraj, B., Jha, A. K., Ausubel, F. M. & Vivanco, J. M. Mediation of pathogen resistance by exudation of antimicrobials from roots. Nature 434, 217–221 (2005).

Peiffer, J. A. et al. Diversity and heritability of the maize rhizosphere microbiome under field conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 6548–6553 (2013).

Qin, D. et al. Microbial assemblages of Schisandraceae plants and the correlations between endophytic species and the accumulation of secondary metabolites. Plant Soil 483, 85–107 (2023).

Tang, S. et al. Impact of N application rate on tea (Camellia sinensis) growth and soil bacterial and fungi communities. Plant Soil 475, 343–359 (2022).

Fradin, E. F. & Thomma, B. P. H. J. Physiology and molecular aspects of Verticillium wilt diseases caused by V. dahliae and V. albo-atrum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7, 71–86 (2006).

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naïve Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261–5267 (2007).

Magoc, T. & Salzberg, S. L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963 (2011).

Wang, Y. F., Liu, L., Yue, F. X. & Li, D. Dynamics of carbon and nitrogen storage in two typical plantation ecosystems of different stand ages on the Loess Plateau of China. PeerJ 7, e7708 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Humic acid fertilizer improved soil properties and soil microbial diversity of continuous cropping peanut: A three-year experiment. Sci. Rep. 9, 12014 (2019).

Gregory, J. C. et.al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature methods. 7, 335–336 (2010).

Adrain, J. M., Westrop, S. R., Chatterton, B. D. E. & Ramsköld, L. Silurian trilobite alpha diversity and the end-Ordovician mass extinction. Paleobiology 26, 625–646 (2000).

Chao, A. Nonparametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand. J. Stat. 11(4), 265–270 (1984).

Raaijmakers, J. M., Paulitz, T. C., Steinberg, C., Alabouvette, C. & Moënne-Loccoz, Y. The rhizosphere: A playground and battlefield for soilborne pathogens and beneficial microorganisms. Plant Soil 321, 341–361 (2009).

Zhou, L. S., Li, H., Zhang, Y., Han, S. Q. & Xu, H. Development of genus-specific primers for better understanding the diversity and population structure of Sphingomonas in soils. J. Basic Microbiol. 54, 880–888 (2014).

Hu, L. F. et al. Root exudate metabolites drive plant-soil feedbacks on growth and defense by shaping the rhizosphere microbiota. Nat. Commun. 9, 2738 (2018).

Tan, S. Y. et al. The effect of organic acids from tomato root exudates on rhizosphere colonization of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens T-5. Appl. Soil Ecol. 64, 15–22 (2013).

Berg, G. et al. Plant microbial diversity is suggested as the key to future biocontrol and health trends. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 93, 1–9 (2017).

Ling, N. et al. The response of root-associated bacterial community to the grafting of watermelon. Plant Soil 391, 253–264 (2015).

Berlanas, C. et al. The fungal and bacterial rhizosphere microbiome associated with grapevine rootstock genotypes in mature and young vineyards. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1142 (2019).

Bulgarelli, D. et al. Structure and function of the bacterial root microbiota in wild and domesticated barley. Cell Host Microbe 17, 392–403 (2015).

Zuo, J. J., Zu, M. T., Liu, L., Song, X. M. & Yuan, Y. D. Composition and diversity of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere of the Chinese medicinal herb Dendrobium. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 127 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. The structure and function of the global citrus rhizosphere microbiome. Nat. Commun. 9, 4894 (2018).

Zhao, J. et al. Influence of straw incorporation with and without straw decomposer on soil bacterial community structure and function in a rice-wheat cropping system. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 4761–4773 (2017).

Upchurch, R. A. et al. Differences in the composition and diversity of bacterial communities from agricultural and forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40, 1294–1305 (2008).

Priyadharsini, P. & Dhanasekaran, D. Diversity of soil Allelopathic Actinobacteria in Tiruchirappalli district, Tamilnadu, India. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 14, 54–60 (2015).

Cho, H., Kim, M., Tripathi, B. M. & Adams, J. M. Changes in soil fungal community structure with increasing disturbance frequency. Microbial Ecol. 74, 62–77 (2016).

Lazzaro, A., Hilfiker, D. & Zeyer, J. Structures of microbial communities in Alpine soils: Seasonal and elevational effects. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1330 (2015).

Naether, A. et al. Environmental factors affect acidobacterial communities below the subgroup level in grassland and forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 7398–7406 (2012).

Ramirez, K. S., Craine, J. M. & Fierer, N. Consistent effects of nitrogen amendments on soil microbial communities and processes across biomes. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 1918–1927 (2012).

Brewer, T. E., Handley, K. M., Carini, P., Gilbert, J. A. & Fierer, N. Genome reduction in an abundant and ubiquitous soil bacterium ‘Candidatus Udaeobacter copiosus’. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16198 (2017).

Zhou, X. G. & Wu, F. Z. p-Coumaric acid influenced cucumber rhizosphere soil microbial communities and the growth of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum owen. PLoS ONE 7, e48288 (2012).

Dong, Y., Dong, K., Zheng, Y., Tang, L. & Yang, Z. Faba bean fusarium wilt (Fusarium oxysporum) control and its mechanism in different wheat varieties and faba bean intercropping system. J. Appl. Ecol. 25, 1979–1987 (2014).

Gaspar, Y. M. et al. Field resistance to Fusarium oxysporum and Verticillium dahliae in transgenic cotton expressing the plant defensin NaD1. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 1541–1550 (2014).

Kara, E. L., Hanson, P. C., Hu, Y. H., Winslow, L. A. & McMahon, K. D. A decade of seasonal dynamics and co-occurrences within freshwater bacterioplankton communities from eutrophic Lake Mendota, WI, USA. ISME J. 7, 680–684 (2013).

Zhang, B. G., Zhang, J., Liu, Y., Shi, P. & Wei, G. H. Co-occurrence patterns of soybean rhizosphere microbiome at a continental scale. Soil Biol. Biochem. 118, 178–186 (2018).

Faust, K. & Raes, J. Microbial interactions: From networks to models. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 538–550 (2012).

Zhao, Z. et al. Protist communities are more sensitive to nitrogen fertilization than other microorganisms in diverse agricultural soils. Microbiome 7, 33 (2019).

Fan, K. K. et al. Biodiversity of key-stone phylotypes determines crop production in a 4-decade fertilization experiment. ISME J. 15, 550–561 (2020).

Lu, L. H. et al. Fungal networks in yield-invigorating and -debilitating soils induced by prolonged potato monoculture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 65, 186–194 (2013).

Coyte, K. Z., Schluter, J. & Foster, K. R. The ecology of the microbiome: Networks, competition, and stability. Science 350, 663–666 (2015).

Lear, G., Bellamy, J., Case, B. S., Lee, J. E. & Buckley, H. L. Fine-scale spatial patterns in bacterial community composition and function within freshwater ponds. ISME J. 8(8), 1715–1726 (2014).

Ranjard, L. et al. Turnover of soil bacterial diversity driven by wide-scale environmental heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 4, 1434 (2013).

Ma, B. et al. Distinct biogeographic patterns for Archaea, Bacteria, and Fungi along the vegetation gradient at the continental scale in Eastern China. mSystems 2, e00174 (2017).

Fukami, T. Historical contingency in community assembly: Integrating niches, species pools, and priority effects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 46, 1–23 (2015).

Moeller, A. H. et al. Dispersal limitation promotes the diversification of the mammalian gut microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 13768–13773 (2017).

Qi, X. J., Wang, E. S., Xing, M., Zhao, W. & Chen, X. Rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere bacterial community composition of the wild medicinal plant Rumex patientia. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 28, 2257–2265 (2012).

Khalediyan, N., Weisany, W. & Schenk, P. M. Arbuscular mycorrhizae and rhizobacteria improve growth, nutritional status and essential oil production in Ocimum basilicum and Satureja hortensis. Ind. Crops Prod. 160, 113–163 (2020).

Vafadar, F., Amooaghaie, R. & Otroshy, M. Effects of plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on plant growth, stevioside, NPK, and chlorophyll content of Stevia rebaudiana. J. Plant Interact. 9, 128–136 (2014).

Bharti, N., Yadav, D., Barnawal, D., Maji, D. & Kalra, A. Exiguobacterium oxidotolerans, a halotolerant plant growth promoting rhizobacteria, improves yield and content of secondary metabolites in Bacopa monnieri (L.) Pennell under primary and secondary salt stress. World J. Microbial. Biotechnol. 29, 379–387 (2013).

Shuai, S. et al. Studies on the composition and diversity of seagrass Ruppia sinensis rhizosphere mmicroorganisms in the Yellow River Delta. Plants 12, 1435 (2023).

Nagarajan, S. et al. Chapter 15—Actinobacterial enzymes—An approach for engineering the rhizosphere microorganisms as plant growth promotors. In Rhizosphere Engineering (eds Nagarajan, S. et al.) 273–292 (Elsevier, 2022).

Shi, Z. B., Yang, Y. M., Fan, Y. H., He, Y. & Li, T. Dynamic responses of rhizosphere microorganisms to biogas slurry combined with chemical fertilizer application during the whole life cycle of rice growth. Microorganisms 7, 1755 (2023).

Meng, L. B., Cheng, Z. Y. & Li, S. M. Response of soil nitrogen-cycling genes to the coupling effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation and biochar application in maize rhizosphere. Sustainability 8, 1 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Effects of hot pepper stalks on rhizosphere microflora structure of Polygonatum kingianum. Microbiol. China 1, 1–21 (2022).

Beeckmans, S. & Xie, J. P. Glyoxylate cycle. In Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences (eds Beeckmans, S. & Xie, J. P.) (Elsevier, 2015).

Yuan, M. M. et al. Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 343–348 (2021).

Wang, C. Y., Pei, X. H., Yue, S. S. & Wen, Y. N. The response of Spartina alterniflora biomass to soil factors in Yancheng, Jiangsu Province, P.R. China. Wetlands 36, 229–235 (2016).

Xiao, X., Fan, M. C., Wang, E. T., Chen, W. M. & Wei, G. H. Interactions of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and soil factors in two leguminous plants. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 8485–8497 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data are accessible at the NCBI-SRA under the accession number PRJNA909426.

Funding

This study was funded by the Major Projects of Science and Technology Plan of Dali-state (D2019NA03): Li Jian Expert Workstation of Yunnan Province (2020-1)-(202005 AF150013). The National Natural Science Foundation projects, (81960696). The Top-level Project of Basic Research Program of Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department (202101AT070001, 202301AT070898).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the experimental design oversight. J.L. and Y.Q. analysed the data. J.L.,W.Y., and Y.Q. wrote the draft. M.Y., B.D., Y.Z. interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. C.X. and Y.Y. supervised the project. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Qian, Y., Yang, W. et al. Elucidating the interaction of rhizosphere microorganisms and environmental factors influencing the quality of Polygonatum kingianum Coll. et Hemsl.. Sci Rep 14, 19092 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69673-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69673-0