Abstract

This paper introduces a new latent variable probabilistic framework for representing spectral data of high spatial and spectral dimensionality, such as hyperspectral images. We use a generative Bayesian model to represent the image formation process and provide interpretable and efficient inference and learning methods. Surprisingly, our approach can be implemented with simple tools and does not require extensive training data, detailed pixel-by-pixel labeling, or significant computational resources. Numerous experiments with simulated data and real benchmark scenarios show encouraging image classification performance. These results validate the unique ability of our framework to discriminate complex hyperspectral images, irrespective of the presence of highly discriminative spectral signatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spectroscopy is a powerful and fascinating scientific tool used to study and analyse the properties of light or electromagnetic emission and reflection. It enables scientists to gain valuable insights into the composition, structure, and physical properties of various objects and phenomena, ranging from celestial bodies like stars and galaxies to microscopic samples in laboratories1,2. By examining spectral patterns, spectroscopy provides a wealth of information about chemical composition, temperature, density, velocity, and other characteristics. It has applications in a wide range of disciplines, including astronomy3, chemistry4, physics5, environmental science6, and materials science7 to name a few and plays a fundamental role in advancing our understanding of the universe and the world around us.

In practice, the use of spectroscopy brings with it a number of challenges that researchers and technicians frequently face. These range from rather practical considerations, such as issues of cost, hardware maintenance, and calibration8 given the expense and complexity of the instrumentation involved, to more specific problems, such as experimental design, sample preparation, noise reduction9, environmental issues (illumination, humidity, atmospheric conditions), different spectral corrections10,11 and spectral resolution competence for particular applications12.

Imaging spectroscopy13 represents an important step in increasing the complexity of the wide range of existing remote sensing, field and laboratory spectroscopic techniques, as it multiplies the amount of data available by incorporating the spatial dimension. Specifically in the field of reflectance spectroscopy14,15, with the advent of multispectral and hyperspectral imaging16, the main challenge is the handling of large amounts of data and the consequent inference from them. However, this challenge also requires data quality assurance to deal with poor and/or noisy measurements, an approach to manage the high dimensionality of the data (curse of dimensionality) and, most especially, consideration of the high cost of annotating and labelling data to make it suitable for supervised methods17.

In this context, a huge variety of techniques have been used to handle (process and learn from) this data; the amount of literature is overwhelming and must be examined for specific applications – for quite comprehensive recent reviews, see18,19,20. To mention a few of the most relevant applications, there are numerous techniques for noise reduction21, baseline correction and normalisation22,23 and feature extraction techniques24,25, such as dimensionality reduction methods26,27,28,29, like principal component analysis (PCA)30.

For the classification problem, techniques range from the most classical – where the best results seem to have been obtained with SVM31 (among random forests32, adaboost33, active learning34) – to more recent ones, using machine learning35,36,37,38,39,40,41 and deep learning techniques42,43,44,45. Such models require large amounts of (annotated) data for effective training, so data augmentation techniques such as spectral interpolation or augmentation based on physical principles have been tried to cope with data scarcity46. Finally, since spectral data can show significant variations due to factors such as those mentioned above (instrument calibration, sample preparation or measurement conditions), sophisticated transfer learning techniques have been used, where models are pre-trained on large spectral datasets and fitted to specific tasks by exploiting prior knowledge47,48,49.

Overall, conventional strategies designed to discriminate a hyperspectral image require supervised data (at the pixel level) and the generation of models trained with this information. The objective is to discriminate specific phenomenological identities (according to the meaning introduced below in “A hierarchical imaging model for spectroscopy”, which refers to the labels of supervised methods), from spectral signatures, in the Fourier domain at the pixel level. Fundamentally, all the methods presented have a common denominator: they rely on a feature-based discrimination hypothesis. There is no doubt that this feature-based approach has proven to be a powerful strategy in many areas of machine learning and pattern recognition. However, in the challenging context of hyperspectral image classification, its adoption has several limitations. In this regard, we can mention the following:

-

Spectral signature existence. It is widely accepted that there is a specific link between the phenomenon under investigation and certain spectral features that typically require pixel-wise extraction and processing. This applies to conventional techniques, such as the well-known spectral angle mapper (SAM), and its derivatives (matched filtering, unmixing, etc.)50,51, as well as the more sophisticated methods mentioned above. However, difficulties arise when the sensor fails to capture the spectral signature of the phenomenon being studied. In this case, it is usual to state that the phenomenon is not active in the spectra recorded by that sensor.

-

Spectral signature extraction. Given the usual association between the phenomenon and its spectral features, in the implementation or deployment of classification or regression methods, a key requirement is to identify, extract and analyse the spectral signature, that is linked to the phenomenon being studied. In other words, the focus is on discovering discriminative features in the Fourier domain. In carefully controlled laboratory settings, this approach could be acceptable . However, in field conditions or in remote sensing applications, it is virtually impossible to control even the most basic parameters (acquisition noise, atmospheric conditions, incident light, circulating dust, ambient and sample humidity, instrument calibration, among many others). Then robust and discriminate feature extraction becomes very challenging52.

-

Partial and noisy labelling. To construct effective inference models, the data needs to be labeled for supervised training53. In the context of hyperspectral imaging, this is a major limitation since a single sensor capture may comprise millions of spectral measurements where pixel-based high resolution labelling would be required. Therefore, it is necessary to deal with the absence of labels (unsupervised or partially supervised learning) or with noisy labels for robust learning.

Given these limitations, in this paper we propose a radically different perspective for the treatment of hyperspectral images, in particular for their classification. Our philosophy models the imaging process in a way that is consistent with the hidden nature of the relationship between phenomena and their spectral expression in a generative approach.

Contribution of this work

We propose a generative model-based approach to hyperspectral image analysis and classification, which takes full advantage of the spectral depth and spatial resolution provided by current hyperspectral imaging technology. Specifically,

-

We introduce a new hierarchical-Bayesian generative model that allows to statistically represent the formation process of a hyperspectral image. Despite its simplicity, this model is endowed with several layers of abstraction and information. Unlike traditional methods, our approach does not rely on a strong discriminative assumption at the pixel level – through assuming the existence of so-called ‘spectral signatures’ or ‘spectral features’. Instead, our model produces descriptions of hyperspectral images at a higher level of semantic abstraction that we call probabilistic spectral signatures.

-

We propose a two-stage inference process that is interpretable, unlike black-box methods (such as deep generative models), and provides a representation of the information extracted from the image sufficient for discrimination. Furthermore, we show that, given certain theoretical and practical conditions, it is possible to make inference using the proposed model without the need to use signatures or spectral features in the traditional sense.

-

We propose an algorithm to implement our inference scheme that can be implemented with simple and straightforward tools. This algorithm is designed based on the clean Bayesian interpretation of our schemes and is built assuming a realistic condition of partial labels and noisy annotations. Consequently, unlike conventional strategies, our training strategy does not require abundant and expensive pixel-level annotations and is robust to occlusion, missing spectral observations and poor spectral detection conditions, as well as being computationally efficient by keeping the number of parameters to be fitted very low.

-

Finally, we designed synthetic scenarios to validate the learning and discrimination capability of our model. We also tested our framework in numerous experimental conditions with real data and known benchmarks. Surprisingly, our strategy delivers impressive performance and state-of-the-art results on known hyperspectral imaging benchmarks.

Related work

In the recent literature we can find works that incorporate generative-Bayesian elements for the analysis and classification of hyperspectral images. For example, new alternatives have been proposed to improve the behaviour of Variational Autoencoders (VAE), in data augmentation tasks54,55, where the efforts are in incorporating the dimensions of spatial and spectral correlation or in regularising the latent space, to improve the quality of the augmented data produced. The same happens with the recent use of Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN), where the focus is on improvements such as reducing the dimensionality of the generated data56 or the use of complementary networks, which work at the patch level and capture semantic contexts or low-level textures57. However, all these works occur in the context of spectroscopy based on spectral features in the traditional sense. Our proposal is an out-of-the box thinking effort consistent with the evolution of spectral sensors (which nowadays generate both spectral and high-dimensional spatial data) to model them directly in an abstract way. In this sense, the mentioned Bayesian frameworks (VAE and GAN) are used integrated in the context of black-box architectures, and not in a bare form as direct modelling.

Paper outline

In order to present the proposed ideas in a hopefully clear way, we have structured this paper as follows: in “A hierarchical imaging model for spectroscopy” we present, in great detail, the proposed model, its components and assumptions; in “The exact inference process” we show how inference is obtained from it, particularly how to arrive at the expressions (12) and (15), which we believe are the central message of this paper, since they show that it is indeed possible to make inference without the need to use the classical spectral signatures; in “Learning the generative model” we provide a simple and straightforward implementation scheme of the model; in “Analysis with synthetic data” and “Experiments with real data” we show a detailed analysis of experiments with synthetic and real data; and finally, in “Conclusion” we provide a final discussion of the paper.

Notations

Upper case letters are used to denote a random variable, X, and lower case letter, x, indicates a particular value for X. Bold letter \(\textbf{X}\) are used to represent random vectors or, more generally, an indexed collection of random variables. The distribution of a random variable X is denoted by \(P_X\) and the distribution of a random vector \(\textbf{X}\) is denoted by \(P_\mathbf{{X}}\). A finite-alphabet space is denoted by \([N]\equiv \left\{ 1,\ldots ,N \right\}\), where \(\mathcal {P}([N])\) represents the family of probabilities on [N]. By the notation \(Z \rightarrow T \rightarrow X\), we mean that Z and X are independent given T58,59.

A hierarchical imaging model for spectroscopy

The central idea of our model is that it formulates in an abstract way how an ideal hyperspectral image \(\textbf{X}=(X_{(i,j)})\) is produced in purely statistical terms, with the intention of abstracting from any particular sensor – this is what is known in the literature as a generative model60; we mention this to avoid confusion with generative AI, so much in vogue today, where a generative model is embedded within a deep learning architecture61. We consider, then, that there is a phenomenon, encoded in Z (whose nature is also abstract; in practice, it can be anything possible to be measured by a particular hyperspectral sensor) which is captured in image \(\textbf{X}\). Between these two elements, we assume that there is a hidden or latent, i.e. unmeasured, process \(\textbf{T}=(T_{(i,j)})\) that organises the pixels of \(\textbf{X}\) into meaningful populations. The graph of the proposed model is very simple and can be summarised as follows

It is inspired by ideas used to model time series (hidden Markov models) and texture images (hidden Markov tree-indexed structures)62,63. Note that \(\textbf{T}\) represents a hidden state at the pixel level, while Z encodes what an expert or a gold standard test can identify in what we will call phenomenological identity on the global image scale, in terms of an arbitrary (eventually scalar) category – for example, \(z = 1\) can be a type 1 material, \(z = 2\) a type 2, and so on. In short, there is an underlying phenomenon in the sensed object, which is abstract, there is an identification at the level of labelling, by an informed observer, which we call the phenomenological identity Z, and there is a set of possible values for this identity of the type \({z_1,\cdots ,z_n}\) which are those we would like to infer by means of a classifier.

Bayesian formulation of the model

Then, the graph (1) represents the forward generation of a hyperspectral image using three layers of random objects. The first layer is a discrete random variable \(Z \in \mathcal {Z}= [M] \equiv \left\{ 1 \ldots M \right\}\) that represents the higher-level phenomenological identity of \(\textbf{X}\) that we want to infer. Next, we consider a discrete hidden random image \(T_{i,j}\in [N] \equiv \left\{ 1 \ldots N \right\}\) with \((i,j)\in [L] \times [K]\) that represents the “hidden population identity” of the hyperspectral information sensed at position (i, j). The set [N] indicates the possible population identities at the pixel level. In this context, Z determines the distribution of the random field \(\textbf{T} \equiv (T_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\) by the conditional distribution \(P_{\textbf{T}|Z}(\cdot |\cdot )\). Finally, the observed image is a collection of high-dimensional random vectors \(X_{i,j}\in \mathbb {R}^m\) (spectral observations) where \((i,j)\in [L] \times [K]\). At this stage, \(\textbf{T}\) determines the distribution of \(\textbf{X} \equiv (X_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\) by the conditional distribution \(P_{\textbf{X}|\textbf{T}}(\cdot |\cdot )\).

Consequently, the joint distribution of the hierarchical model \((Z, \textbf{T}, \textbf{X})\) for the conditional independent Markov structure of the graph in Eq. (1) has the following factorization:

Elements of the Bayesian model

Here we present in detail the central assumptions of the model. The aim is that these are general and sufficient to allow inference of Z (“The exact inference process”) without particular distributional assumptions.

We assume a permutation invariant symmetry in the model, which is common for spatially organised objects and natural images63,64,65 and refine the general structure of \(P_{Z, \textbf{T}, \textbf{X}}\) in (2) as follows:

-

i)

From (2), Z determines the distribution of the population image \(\textbf{T}\). Conditioning on \(Z=z\in [M]\), we assume that \((T_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\) are independent random variables with \(T_{i,j}\) following the same distribution \(v_z = P_{\textbf{T}|Z = z} \in \mathcal {P}([N])\) for any position (i, j). Then, for any product event \(B=\bigotimes _{(i,j) \in [L] \times [K]} B_{i,j}\) where \(B_{i,j} \subset [N]\) – i.e. joint events of population identities occurring in \(\textbf{T}\) – we have that

$$\begin{aligned} P_{\textbf{T}|Z} (B|z)= \prod _{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]} P_{T_{i,j}|Z}(B_{i,j}|z) = \prod _{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]} v_z(B_{i,j}). \end{aligned}$$(3)The i.i.d. structure in (3) models the assumption that the hidden pixel-wise population identity is an attribute invariant to pixel permutations. In “Stage 1: Pre-processing” we present the implementation solution to this aspect when it comes to real images that strangely meet the aforementioned assumption.

-

ii)

On the other hand, we assume a pixel-by-pixel conditional independent structure between \(\textbf{T}\) and \(\textbf{X}\). More precisely, given the value of \(T_{i,j}=t_{i,j}\in [N]\) the random vector \(X_{i,j}\) is independent of all the other positions of the random image \(\textbf{X}\). Then, \(T_{i,j}\) acts as a discrete hidden state of \(X_{i,j}\) (like a hidden Markov model (HMM)) for any pixel position (i, j). Formally, we have that for any discrete set of states \(\textbf{t}= (t_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]} \in [N]^{L\cdot K}\) and for any product observation event \(A=\bigotimes _{(i,j) \in [L] \times [K]} A_{i,j}\) where \(A_{i,j} \subset \mathcal {B}(\mathbb {R}^m)\) occurring in \(\textbf{X}\):

$$\begin{aligned} P_{\textbf{X}|\textbf{T}} (A|\textbf{t})= \prod _{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]} P_{X_{i,j}| T_{i,j}}(A_{i,j}| t_{i,j}) = \prod _{(i,j) \in [L] \times [K]} \mu _{t_{i,j}}(A_{i,j}), \end{aligned}$$(4)where \(\mu _{t_{i,j}}(\cdot )\) represents the observation probability in \(\mathbb {R}^m\) of our image model. Then, at this final stage, the model is equipped with the following discrete collection of observation probabilities: \(\left\{ \mu _t (\cdot ), t = 1\ldots N \right\} \subset \mathcal {P}(\mathbb {R}^m)\).

The hidden Markov conditional independent structure of the triplet \((Z, \textbf{T}, \textbf{X})\) is illustrated in Fig. 1.

In summary, our hierarchical model has three components:

-

a)

Phenomenological identity level (Z): \(P_Z=(p_Z(1),\ldots ,p_Z(M)) \in \mathcal {P}([M])\) that models the prior distribution of the underlying identity.

-

b)

Hidden state level (\(\textbf{T}\)): \(\left\{ v_1 \ldots v_M \right\} \subset \mathcal {P}([N])\) that models the collection of conditional distributions of the hidden (or target) state \(\textbf{T}\) given Z in (3).

-

c)

Spectral level (\(\textbf{X}\)): \(\left\{ \mu _1\ldots \mu _N \right\} \subset \mathcal {P}(\mathbb {R}^m)\) that models the collection of conditional continuous distributions of \(\textbf{X}\) given \(\textbf{T}\) in (4).

Thus, the hierarchical model given by \(\Lambda =(P_Z, \left\{ v_1 \ldots v_M \right\} , \left\{ \mu _1\ldots \mu _N \right\} )\) offers a complete characterization of the joint distribution of \((Z,\textbf{T},\textbf{X})\) using (2), (3) and (4).

The probabilistic spectral signature

The level of the population identity of our model (i.e., the hidden state \(\textbf{T}\)) is essential. In this domain, Z induces a finite collection of discrete probabilities \(\mathcal {H} = \left\{ v_1 \ldots v_M \right\} \subset \mathcal {P}([N])\). Then, our main task is to infer Z from \(\textbf{X}\). The latter set of discrete distributions represent the hidden probabilistic identity of the spatial observation \(\textbf{X}\) in the model space \(\mathcal {P}([N])\) (which is the simplex of dimension \(N-1\)). These models can be understood as the “probabilistic spectral signatures” of \(\textbf{X}\). In this context, the discrimination condition \(v_i \ne v_j\) is required for any pair in the hypothesis space \(\mathcal {H} = \left\{ v_1, \ldots , v_M \right\}\). The next section elaborates on this model selection interpretation, which is the inference task of using \(\textbf{X}\) (evidence) to select one of the models in \(\mathcal {H} = \left\{ v_1, \ldots , v_M \right\}\) to infer Z.

Graphical structure (directed graph) of the hierarchical model \((Z, \textbf{T}, \textbf{X})\) presented in “Bayesian formulation of the model”.

Relationship between Z and phenomenological identity

To clarify the relationship between Z’s inference and phenomenological identity (\(Ph_{Id}\)), it is worth noting that what we agree to call classical spectroscopy – a technique that relates a spectrum measured by a sensor to a phenomenon that emerges from the observed physical sample, through a set of spectral features in the Fourier domain – can be modelled (almost metaphorically) as

where \(\textbf{S}\) is the spectral signature that can be recognised by the expert by observing the measured spectrum. It is understood that by observing an instance of \(\textbf{S}\) (i.e. \(\textbf{S}=s\)), \(Ph_{Id}\) can be inferred through characterising the probability \(P_Z(z|\textbf{S}=s)\). The decision rule would then be

The exact inference process

To derive an expression analogous to (6), at the inference stage of our model, we assume that we have access to \(\textbf{X} = (X_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\) to infer Z in the classical minimum probability of error (MPE) sense59. This implies implementing the well-known maximum a posteriori (MAP) decision rule: \(Ph_{Id}(\textbf{X}) \equiv \arg \max _{z\in [M]} P_{Z|\textbf{X}}(z| \textbf{X})\). To address this task, we consider the analysis of a simplified oracle setting that provides insight into the discrimination potential of this hierarchical framework, in particular when the image is of (deep) high resolution, i.e., \(L\times K\) is large.

The oracle case: observing \(\textbf{T}\) to infer Z

In the second component of our model, we observe that \(X_{i,j}\) can be interpreted as a noisy data corrupted version of the hidden state variable \(T_{i,j}\) (see Fig. 1). Then, it is insightful to analyze an idealized oracle setting, where we have access to \(\textbf{T}=(T_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\) to discriminate Z in the MPE sense.

By data processing inequality and the Markov structure \(Z \rightarrow \textbf{T} \rightarrow \textbf{X}\) in (2), we know that the inference power of using \(\textbf{T}\) to detect Z is better than using \(\textbf{X}\) instead. In this context, the MAP decision rule computes the log-likelihood scores for any \(Z=z \in [M]\) (or model hypothesis) by

where (\(\textbf{1}_{A} (\cdot )\) is the indicator function.)

\(\mathcal {S}_n\) indicates the number of pixel (i, j) where the condition \(t_{i,j}=n\) holds (ie. the empirical frequency of the event \(\left\{ n \right\}\)). We recognize \(\hat{p} (n) \equiv \mathcal {S}_n/(K \cdot L)\) for any \(n \in [N]\) as the empirical distribution (or histogram) induced by \((t_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\). Therefore,

is the cross-entropy loss of the model \(v_z\) w.r.t. \(\hat{p}\).

Finally, it is simple to verify that for any \(z\in [M]\)

where \(H(p) \equiv - \sum _{n \in [N]} p(n) \cdot \log p(n) \ge 0\) is the Shannon entropy58 and \(D(p||q) \equiv \sum _{n \in [N]} p(n) \log \frac{p(n)}{q(n)} \ge 0\) is the discrete Kullback-Leibler divergence (KLD)66. Integrating (10) and (11) in the MAP rule, we have that the optimal decision is given by

This rule implements a model selection task: a minimum distance decision (using the KLD as a distance) in the space of models \(\mathcal {H} = \left\{ v_1, \ldots , v_M \right\} \subset \mathcal {P}([N])\) (see Fig. 2). Importantly, the empirical distribution \(\hat{p} \in \mathcal {P}([N])\) obtained from the population information \(\textbf{T}\) represents a sufficient statistic for the task. Then, \(\hat{p}\) can be interpreted as an empirical model that summarises the evidence obtained from \(\textbf{T}\). The two-stages (data summary and decision) of this inference process are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Note that the second term of the Eq. (12) contains the a priori distribution (or information) of the phenomenon, encoded in the ‘phenomenological identity’ Z, which in practice includes knowledge about the associated spectral features, if they exists. This implies that if the spatial resolution \([L] \times [K]\) is sufficiently high, this term disappears, leaving the inference capability of the model in the information contained in \(\textbf{T}\), the sufficient statistic.

The two stages needed to implement the MPE decision in (12) for the oracle setting where \(\textbf{T}\) is used to infer Z.

Observing X (a noisy version of T) to infer Z

However, in our Markov structure \(Z \rightarrow \textbf{T} \rightarrow \textbf{X}\), we observe \(\textbf{X}\) to infer Z, and \(\textbf{T}\) remains unobserved (hidden). As in our setting, we know the set of population identities in \(\mathcal {P}([N])\) (see “The probabilistic spectral signature”), and we know \(P_{\textbf{T} | \textbf{X}}\). Then, inspired by the Viterbi algorithm67 a two-stage algorithm can be constructed to infer Z from \(\textbf{X}\) following the oracle decision scheme in (12):

-

1.

Inferring \(\textbf{T}\) from \(\textbf{X}\): At this stage, we use Eqs. (4) and (3) to note that given Z, \((T_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\) are independent component-wise and, consequently, \((X_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\) are independent (component-wise). This implies that for any individual pixel (i, j), \(T_{i,j}\) is independent of \((X_{\tilde{i},\tilde{j}})_{({\tilde{i},\tilde{j}})\ne (i,j)}\) conditioned on \(X_{i,j}\) – by the conditional independence Markov structure \(T_{i,j} \rightarrow X_{i,j} \rightarrow (X_{\tilde{i},\tilde{j}})_{({\tilde{i},\tilde{j}})\ne (i,j) \in [L] \times [K]}\). Therefore, the MPE decision to infer \(T_{i,j}\) given \(\textbf{X} = \textbf{x}=(x_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\) is

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{T}_{i,j}=\arg \max _{t \in [N]} \mathbb {P} (T_{i,j}=t | \textbf{x} ) = \arg \max _{t \in [N]} \mathbb {P} (T_{i,j}=t | x_{i,j}), \end{aligned}$$(13)which is a function that only depends on the single spectrum vector \(x_{i,j}\), i.e., \(\hat{T}_{i,j} = \hat{T}_{i,j}(x_{i,j})\). Then our MPE approximation of \(\textbf{T}\) given \(\textbf{X} = \textbf{x}=(x_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\) is

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{\textbf{T}}(\textbf{x}) = (\hat{T}_{i,j}(x_{i,j}))_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]} \end{aligned}$$(14)where \(\hat{T}_{i,j}(x_{i,j})\) is the solution presented in the RHS of (13) for all positions (i, j).

-

2.

Inferring Z from \(\hat{\textbf{T}}(\textbf{X})\): Using the output of the first stage, i.e., \(\hat{t}_{i,j} \equiv \hat{T}_{i,j}(x_{i,j})\) for all positions (i, j), we implement a noisy version of Eq. (12) using \((\hat{t}_{i,j})_{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]}\):

$$\begin{aligned} Ph_{Id}(\textbf{X} = \textbf{x}) = \tilde{Ph}_{Id}(\hat{\textbf{T}}(\textbf{x})) = \arg \min _{z \in [M]} D(\hat{p}|| v_z) + \frac{1}{K \cdot L} \cdot \log \frac{1}{p_Z(z)} \end{aligned}$$(15)where in this context \(\hat{p}=(\hat{\mathcal {S}}_n/(K\cdot L))_{n\in [N]}\) and

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{\mathcal {S}}_n \equiv \sum _{(i,j)\in [L] \times [K]} \textbf{1}_{ \left\{ n \right\} } (\hat{t}_{i,j}). \end{aligned}$$(16)

In short, given \(\mathcal {H} = \left\{ v_1, \ldots , v_M \right\} \subset \mathcal {P}([N])\) (our probabilistic spectral signatures) and \(P_{\textbf{T} | \textbf{X}}\), we extract the information that X contains to infer the population identities encoded in T, as X can be seen as a noisy but informative version of T. This approximated inference pipeline is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Learning the generative model

We now turn to the challenging task of learning our generative model from real hyperspectral data. We face the realistic context presented in many applications where we only have access to partial information to learn \(P_{Z, \textbf{T}, \textbf{X}}\) in (2). In particular, we tackle the realistic scenario mentioned in the introduction where we have semi-supervised data in the form of a collection of real hyperspectral images (remember that \(\textbf{X}\) is only an idealised representation) with some partial identity annotations: \(\left\{ (\mathcal {I}_1, \tilde{z}_1), \cdots ,(\mathcal {I}_Q, \tilde{z}_Q)\right\}\).

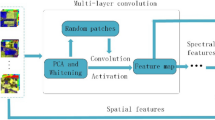

Inspired by ideas raised in the formalism of hierarchical Dirichlet processes68 and generalising the methodology proposed in12, we propose a learning framework that takes into account that we do not have supervised examples of the pairs \((X_{i,j},T_{i,j})\) and, consequently, the proposed latent state is hidden and not observable at the time of learning. This means that we do not know the set of population identities [N], nor do we have direct access to supervised samples to learn the joint distribution \(P_{\textbf{T}, \textbf{X}}\), which is essential to apply the inference method proposed in “Observing X (a noisy version of T) to infer Z”. To meet these challenges, we propose a learning methodology that consists of three stages:

-

Stage 1: Pre-processing: Use the annotated data \(\left\{ (\mathcal {I}_1, \tilde{z}_1) , \cdots ,(\mathcal {I}_Q, \tilde{z}_Q)\right\}\) to produce i.i.d. samples of the pair \((Z,\textbf{X})\) in our model.

-

Stage 2: Inducing the population labels (estimating \(\textbf{T}\)): Introduce a hybrid (unsupervised/supervised) strategy to estimate \(T_{i,j}\) (pixel-level population identities) from \(X_{i,j}\) and, in the process, determine the set of population identities [N] in a data-driven manner.

-

Stage 3: Stage 3: Learning \(P_{Z, \textbf{T}, \textbf{X}}\): Use the supervised sample estimates to learn \(P_{Z, {T}, {X}}\) for the inference process.

Stage 1: Pre-processing

It is reasonable to assume that our partially annotated raw hyperspectral data \(\left\{ (\mathcal {I}_1, \tilde{z}_1) , \cdots ,(\mathcal {I}_Q, \tilde{z}_Q)\right\}\) may have some correlation at the pixel level – natural images are rarely i. i.d. at the pixel level69,70. This is not consistent with our assumption of pixel-level i.i.d. in “Elements of the Bayesian model”. Therefore, an essential part of our implementation strategy is a random spatial sampling process that de-correlates the spatial information presented in the original image. This spatial de-correlation method has proven to be super-efficient and provides a link to many of the i.i.d assumptions of our model. Furthermore, the invariant permutation structure adopted in our model implies a significant reduction in the number of learning parameters, which is an essential element for adopting and deploying our method. As implementation solution, we propose a randomisation scheme to shuffle the pixels contained in \(\{\mathcal {I}_1,\ldots ,\mathcal {I}_Q\}\) and produce i.i.d. samples of the pair \((Z,\textbf{X})\) with only two additional parameters: the sample size n (the number of pixels i.i.d to be sampled from each image \(\mathcal {I}_k\)) and a function \(\mathcal {K}_s: \mathcal {X}=\mathbb {R}^m \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^m\). What this function does is to ‘convolve’ (i.e. guarantees the use of information from) the neighbouring pixels of a given pixel. As a result, it produces an aggregated spectrum (i.e. the average of all neighbouring pixels). In this way it concentrates, at a very local level, the spatial correlation information around a given pixel of a real image – it is not necessary to consider the correlation in larger ranges due to the random sampling that precisely tries to de-correlate it. Implementation details are shown in Appendix A.

Rule of thumb for the determination of the pre-processing function parameters

As defined in Appendix A, the application of the \(\mathcal {K}_s\) function has two parameters, s, which is the size of the averaging kernel on which the local convolution operation is performed on the image, and n, which is the number of times this operation is applied. The value of the first one depends on the type of spatial correlation that the phenomenon of interest has on the image surface. If, for example, it is a dust or sand, \(s=3\) may be a good first value to try. If, on the other hand, it is a more heterogeneous material, where the spatial correlation is on a larger scale, a value of s of one third of one side of the image size, will be a good starting point. As an example, if the image has \(300 \times 300\) pixels, \(s=100\) would be a good starting value. With respect to n usually with a value of 100, for an image of \(500 \times 500\) pixels it can be a good starting point. The convergence of the model is asymptotic with respect to this parameter, so the higher the better. A general rule of thumb would be that \(s \times n\) does not exceed the total number of pixels in the image by too much.

Stage 2: inducing the population labels (estimating \(\textbf{T}\))

This is the most challenging of the three stages. Using the produced i.i.d. samples of \((Z,\textbf{X})\), which we denote by \(\{(\tilde{Z}_1, \tilde{\textbf{X}}_1), \ldots , (\tilde{Z}_J, \tilde{\textbf{X}}_J)\}\) from (Algorithm 1 - Appendix A), we introduce a hybrid unsupervised/supervised strategy to estimate \(\textbf{T}_k\) from \(\tilde{\textbf{X}}_k\), for any image in our collection. Since for any pixel (i, j), \(T_{i,j}\) models the population identity underlying the distribution of \(X_{i,j}\), we exploit the depth of the hyperspectral image and its high-dimensional content to assume that this pixel-level population information is embedded in the unsupervised samples \(\{\tilde{\textbf{X}}_1, \ldots ,\tilde{\textbf{X}}_J\}\). Denoted by \([\tilde{N}]\) the set of such embedded population identities, we train a regressor \(r:\mathcal {X}=\mathbb {R}^m \rightarrow [\tilde{N}]\) that estimates for any hyperspectral vector (pixel i.i.d.) its population index in \([\tilde{N}]\).

In addition, we enrich this inference with the identity labels \(\{\tilde{Z}_1, \ldots , \tilde{Z}_J\}\) that belong to \([Q]=\cup _{i=1}^J \{\tilde{Z}_i\}\). We train a second regressor \(s:\mathcal {X}=\mathbb {R}^m \times [\tilde{N}]\rightarrow [Q]\) that estimates, for any hyperspectral vector with a particular index in \([\tilde{N}]\), the component that can complete the estimation of its specific population identity. Then, for any image \(\tilde{\textbf{X}}_k\) in our collection, we estimate its (hidden) population identity image as

where

Thus, we can say that \([\hat{N]} = [\tilde{N}] \times [Q]\) determines the estimated space of population identities.

For learning the first regressor \(r(\cdot )\), we use \(\tilde{\textbf{X}} = \cup _{i=1}^J \{\tilde{\textbf{X}_i}\}\) and a standard (unsupervised) clustering algorithm \(\mathcal {C}(\cdot )\) that produces a group of \(\tilde{N}\) cells (or clusters) in \(\mathbb {R}^m\) associated with some learned population identities:

where \(\{ \mathcal {C}_1, \cdots , \mathcal {C}_{\tilde{N}} \}\) are the cells that partition the space. Then, for \(\textbf{x} \in \tilde{\textbf{X}}\), \(r(\textbf{x}) = k\) if \(\textbf{x} \in \mathcal {C}_k\).

To learn the second regressor \(s(\cdot , \cdot )\), we take advantage of the fact that \([\tilde{N}]\) is a discrete space, which allows us to train \(\tilde{N}\) regressors \(s_k: \mathcal {X}=\mathbb {R}^m \rightarrow [Q]\) (one for each index \(k \in [\tilde{N}]\)) using the samples contained in the corresponding cell \(\mathcal {C}_k\), remembering that each \(\textbf{x} \in \mathcal {C}_k\) has an associated label in \(\{\tilde{Z}_1, \ldots , \tilde{Z}_J\}\) – because it comes from some \(\tilde{\textbf{X}}_i\) taken from the collection \(\{(\tilde{Z}_1, \tilde{\textbf{X}}_1), \ldots , (\tilde{Z}_J, \tilde{\textbf{X}}_J)\}\). Thus, \(s(\textbf{x}, k) = s_k(\textbf{x})\) \(\forall k \in [\tilde{N}]\).

Stage 3: learning \(P_{Z, \textbf{T}, \textbf{X}}\)

Learning the joint model \(P_{Z, \textbf{T}, \textbf{X}}\) from our produced supervised samples \(\{(\tilde{Z}_1, \tilde{\textbf{T}}_1, \tilde{\textbf{X}}_1), \ldots , (\tilde{Z}_J, \tilde{\textbf{T}}_J,\tilde{\textbf{X}}_J)\}\), reduces to implement the inference strategy presented in “Observing X (a noisy version of T) to infer Z”. Therefore, we only need to implement (13) from the model \(P_{Z, \textbf{T}, \textbf{X}}\) and determine \(\mathcal {H} = \left\{ v_1 \ldots v_M \right\} \subset \mathcal {P}([N])\) (our stochastic signatures).

For the first part, i.e. implementing (13), we only need the pixel-wise posterior \(P_{T_{i,j}|X_{i.j}}(\cdot |\cdot )\) which can be estimated from \(\{(\tilde{\textbf{T}}_1, \tilde{\textbf{X}}_1), \ldots , (\tilde{\textbf{T}}_J,\tilde{\textbf{X}}_J)\}\).

For the second part, we need to determine \(\mathcal {H} = \left\{ v_1 \ldots v_M \right\}\). We consider for that

The empirical distribution \(\hat{p}(\cdot )\) is reviewed in the next section “Revisiting the inference process in test condition”.

Revisiting the inference process in test condition

With all the elements of our model in place, it is now relevant to review the inference process of “Observing X (a noisy version of T) to infer Z”. For a given hyperspectral image \(\mathcal {I}\) (in test condition), inference is reduced to determining the empirical distribution (histogram) \(\hat{p}\) in (16). In the context of our learning design, we have

with

and \(\tilde{\textbf{T}}(\tilde{\textbf{X}}_\mathcal {I})=(\tilde{T}_{i,j})_{(i,j) \in [L] \times [K]}\) in a similar way as presented in (17) and (18), and with \(\tilde{\textbf{X}}_\mathcal {I}\) obtained by processing \(\mathcal {I}\) with Algorithm 1 (Appendix A).

Finally, as the dimensionality of the hyperspectral image becomes deep, i.e., \(K \cdot L\) becomes very large, the prior distribution of the phenomenological identity \(Ph_{Id}\) becomes irrelevant, i.e., \(\frac{1}{K \cdot L}\log \frac{1}{p_Z(z)} \approx 0\), leaving all the discrimination power of our model to the histogram \(\hat{p}(\tilde{\textbf{X}}_\mathcal {I})\) in (21). Then from Eqs. (15) and (21), the inference is

Equation (23) summarises the power of the proposed method, when dealing with spatially dense images, as the inference process can be performed on the basis of the experimental a posteriori distribution alone.

The infographic describes the process to generate an image \(\mathcal {I} = (\mathcal {I}_{i,j})_{(i,j) \in [L] \times [K]}\) with the model \(Z \rightarrow \textbf{T} \rightarrow \textbf{X}\). In this specific model instance, \(\textbf{X} = \mathcal {I}\), the associated label (phenomenological identity) is \(\tilde{z}_k\), \(\mathcal {I}_{i,j} \sim N(\varvec{\mu }_{i,j}, \sigma ^2I_m)\) and \(\varvec{\mu }_{i,j} \sim v_k(\varvec{\mu }_1, \cdots , \varvec{\mu }_Q)\).

Analysis with synthetic data

We begin our experimental analysis with a controlled simulated setting following the generative construction presented in “A hierarchical imaging model for spectroscopy”. The aim is to test the elements presented in our inference strategies and the steps of the learning method presented in “Learning the generative model” under controlled conditions.

Data generation

For the generation of the data, we consider the three layers (“Elements of the Bayesian model”) of the model (1) to build a Gaussian observation model with a hidden discrete latent variable (as illustrated in Fig. 4):

-

Phenomenological identity level (Z): A finite set \(\left\{ \tilde{z}_1, \cdots ,\tilde{z}_Q\right\}\) of labels that induce a set of \(Q=4\) phenomenological identities presented at the top of Fig. 4.

-

Hidden state level (\(\textbf{T}\) or pixel population identities): Concerning \(P_{T_{i,j}|Z}\), this is captured in the hypothesis space \(\mathcal {H} = \left\{ v_1 \ldots v_Q \right\}\), which are the probabilistic signatures of hyperspectral identities.

-

Spectral level (\(\textbf{X}\) or \(\mathcal {I}\) in Fig. 4): For each value of variable \(T_{i,j}=k\in [N]\), we consider that \(X_{i,j}|T_{i,j}=k\sim N(\varvec{\mu }_{i,j},\sigma ^2 I_m)\) where the mean vectors are in the known set \(\{\varvec{\mu }_1, \cdots , \varvec{\mu }_Q\}\) and the scalar parameter \(\sigma ^2\) represents the precision of the sensor.

In this setting, we have the following:

-

We consider m “spectral bands” for the observation \(X_{i,j}\) (indexed by the pixel of the image).

-

The \(\mathcal {K}_s(q)=q\) patch function is used: the images are generated without spatial correlation among pixels.

-

We consider \(L=K=100\).

Then, our data generation model can be summarised as

for the set \(\mathcal {H} = \left\{ v_1 \ldots v_Q \right\}\), where \(\varvec{\mu }_h = (\mu _p^{(h)})_{p \in \{1, \cdots , m\}} \in \mathbb {R}^m\) are vectors of known fixed means. We define that

Then, the hypothesis model \(v_k\) merely randomly chooses a known mean using a discrete probability with weights \(\{w_1^k, \cdots , w_Q^k\}\).

The process to generate an image \(\mathcal {I} = (\mathcal {I}_{i,j})_{(i,j) \in [L] \times [K]}\), with an associated label \(\tilde{z}_k\), is set as

Figure 5 shows the hypothesis models (probability mass function) used for each \(v_k\). In each case, the model is a signature of the label \(\tilde{z}_k\) with which that model is associated. The frequencies of the histogram \(v_k\) are the weights \(\{w_1^k, \cdots , w_Q^k\}\).

Confusion in the pixel domain (\(\sigma ^2\))

In our analysis, \(\sigma ^2\) is used to control the level of confusion between the population identities associated with the pixels of \(\mathcal {I}\). Varying \(\sigma ^2\) not only produces confusion at the pixel level, but also produces scenarios with different spectral variability. Figure 6 illustrates different levels of confusion for the \(m=2\) case. Note that, as the means are in \([0, 1]^2\), for \(\sigma ^2 > 1\) the classes are indistinguishable, which is how we are simulating phenomenological mixtures in the space of observations (images). Large \(\sigma\)s are considered to avoid misleading conclusions in a trivial (non-challenging) domain where the variance is low.

Training

In this analysis, the algorithm is trained with k-means as the clustering function \(\mathcal {C}(\cdot )\) (with 10 target clusters) and with simple logistic regressions (with the default penalty rule \(l_2\)) as the functions that implement the regressor \(s(\cdot , \cdot )\).

Checking the hypothesis models inference

First, we are interested in verifying the ability of the learning algorithm (in “Learning the generative model”) to estimate the true models (pmf) from the observations. To do this, 20 synthetic training images are generated, 5 for each \(\tilde{z}_k\) (\(k \in \{1, \cdots , Q = 4\}\)) with \(m=300\) bands (enough to be hyperspectral) and a confusion \(\sigma ^2 = 3\) which is large enough, so that the clustering stage is not an over-simplistic task; this is elaborated in “Pixel-level confusion sensitivity analysis”).

We then train the algorithm for different sample sizes n and verify how the inferred models approach the true models as n increases (see Fig. 7). It can be seen that for \(n = 100\) (\(1\%\) of the original pixel) the inference is poor, but from \(n = 1000\) (\(10\%\) of the original pixels) onwards, the inferences of the models are very accurate.

Pixel-level confusion sensitivity analysis

The idea now is to verify how the algorithm behaves for different numbers of spectral bands (m) with respect to the level of pixel-level confusion \(\sigma\); Table 1 shows a nomenclature of sensors for different ms.

For this purpose, 50 data sets of 100 images each are generated for each combination of \(m \in \{3, 30, 100, 300, 1000\}\) and \(\sigma ^2 \in \{0.01, 0.05, 0.08, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, 300, 500\}\). The inference algorithm is then trained on \(20\%\) of each data set, using the same hypothesis models and parameters (and hyperparameters) as for “Checking the hypothesis models inference”, and the remaining \(80\%\) is used to test and infer the class of each image and calculate the classification accuracy. Table 1 and Fig. 8 (logarithmic in x) show the results.

Accuracy reached by models trained with 50 data sets of 100 images each, generated for each combination of \(m \in \{3, 30, 100, 300, 1000\}\) and \(\sigma ^2 \in \{0.01, 0.05, 0.08, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, 300, 500\}\). The inference algorithm is trained on \(20\%\) of each data set and the remaining \(80\%\) is used to test and infer the class of each image.

It can be observed that

-

At lower levels of confusion (\(\sigma ^2 < 0.1\)), the results are very accurate, as expected, since the clustering algorithm is the one that seems to separate the classes correctly, regardless of the size (depth) of the observation (spectral) domain.

-

Remarkably, perfect classifications (\(100\%\) accuracy) are obtained for \(m = 1000\), up to \(\sigma ^2 = 100\), which is an impressively large level of confusion in this context. In the realm of high-dimensional hyperspectral domain, the inherent separability of objects persists despite the considerable pixel-level confusion they exhibit. Then, the higher the m, the higher the level of pixel-level confusion supported by the method will be.

Experiments with real data

In this section, we present four sets of classification experiments with real data. Each is explained, in objective and scope, in its corresponding section. These are presented in order of increasing difficulty for our model and method.

The first experiment aims to show the behaviour of our model in a classification application, on public domain satellite hyperspectral images, whose ground truth has been built at the level of individual labelled pixels, which is an idealized situation from the point of view of Stochastic Image Spectroscopy. This has led us to adapt our method, in order to have noisy labelled sub-images, as required by the presented model.

The second and third experiments represent major challenges for the method as they consider a database of hyperspectral images taken on comminuted mixed mineral samples, at a spatial resolution such that each pixel contains a high level of mixing. Moreover, the labels are one per image, so they are noisy and refer to the underlying phenomenon or phenomenological identity in a general way, based on laboratory analysis or expert indication.

In the case of the fourth experiment, this is a texture classification exercise, on a database of images in RGB format. Due to the low dimensionality of this type of data, a great deal of effort is required of the method in this case.

Regarding the model parameters used, in the second and the fourth experiments, the learning algorithm is trained with k-means as the clustering function \(\mathcal {C}(\cdot )\) (with 10 target clusters) and with simple logistic regressions (with the default penalty rule \(l_2\)) as the functions that implement the regressor \(s(\cdot , \cdot )\). We use \(n = 3000\) for all cases. In all cases, the main difference with the synthetic cases is that, since we are dealing with real images, we need to deal with spatial correlation at the pixel level. In this context, the convolution function used is \(\mathcal {K}_s(q) = w * q\), where “\(*\)” is the convolution operator and w is an averaging kernel of size \(s = 10\) around pixel q. In the case of the first and third experiments, we include parameter sensibility analysis; therefore, there are different values for some of them, which will be described in Sects. "Satellite hyperspectral image classification" and "Classification of mineralogical categories" respectively.

Satellite hyperspectral image classification

As a way to show an application of the method on public data sources, we have chosen three well-known satellite hyperspectral datasets used in multiple image segmentation classification works. These are the Indian Pines71, Salinas and Botswana72 datasets.

A general characteristic of this type of satellite data is that parts of the scenes have been labelled pixel by pixel, with various categories representing types of crops, buildings, tree species, water areas, and so on. From the perspective of our method and our experience, this way of proceeding is an idealisation. It is good to consider the fact that whatever the spatial resolution of the image, there is always a mixture in the same pixel. To make it possible to work with our model, which is multi pixel, and in each sample image we use only one category or noisy label, we have generated a sampling by means of a moving window, of between 4 and 6 pixels per side, over the each satellite image, and we have determined the category of each window-sample by simple voting. In this way, we generated different sets of samples to apply the method, as described below.

For each of the selected satellite hyperspectral datasets we perform different kind of experiments. In the first case (Indian Pines) we performed two leave-one-out runs with different amounts of window samples as described above. In the second case (Salinas) we did a best case search, with varying model parameters s and n and a comparison of results, with two different sampling window sizes. Finally, in the third case (Botswana) a comparison of results was made with respect to the noisiness of the labels of the samples created by the moving window, with variation of the number of samples as an implicit consequence.

Indian Pines

The Indian Pines dataset contains a scene called Site 3, as shown in Fig. 9, which has 16 categories of labelled pixels, including the background. To test this dataset, two different sets of samples were generated from a 25-pixel moving window.

In Table 2 the total number of samples per category generated with the \(5 \times 5\) pixels moving window is shown, and the random collections of samples taken for each experiment (Exp 1 and Exp 2) are shown as well. The total number of samples was generated considering those windows where all pixels had the same label value, except in the case of categories 7 and 9, where due to the low number of available pixels, a simple majority of 10 equal pixels was tolerated.

As shown in Fig. 10 the method delivers correct classification results of 100% for two sub-sets of samples whose detail can be seen in Table 2. In both Leave One Out runs model parameters s and n were fixed at \(3 \times 3\) and 30 respectively.

These results place our model in the state of the art of behaviour for this dataset, as can be seen in the graph in Fig. 11, which shows the Overall Accuracy of the most successful classification methods with this dataset in recent years73,74,75,76.

Salinas

Salinas dataset consists of a scene containing a set of agricultural crops, in some of which the corresponding pixels are labelled one by one with the type of product being grown, with 16 different categories. An overlay of the scene with the classes in colours and a list of the categories is shown in Fig. 12 for reference only. The scene is 217 x 512 pixels.

The first experiment performed with the Salinas dataset consisted of a comparison of results from the variation of the s and n parameters (see Table 3), on a set of 50 samples per category, generated with a \(5 \times 5\) pixel moving window. Samples were randomly selected from the set of all samples per category where all 25 pixels had the same label value.

Figure 13 shows the Leave One Out result for the case of \(s=2 \times 2\) and \(n=20\) in which the Overall Accuracy is 99%. It can be seen that the only confusions that occur are between categories 8 and 15 (Grapes untrained and Vineyard untrained) in a reciprocal way, which is consistent with the result of the second experiment performed on this dataset, shown below.

Best result out of the 9 runs with 50 sample categories for Salinas experiment described in Table 3.

Figure 14 shows the result of two Leave One Out runs for 150 samples per category. In the first run, a 25-pixel moving window was used, with \(s=2 \times 2\) and \(n=30\) and in the second run a 36-pixel moving window was used, with \(s=2 \times 2\) and \(n=40\). An increase in OA is observed in the second case and it is also observed that the categories that are confused are the same as in the case of the first experiment. Although an intensive Greed Search for the parameters has not been performed here, it is understood that possibly even a better behaviour of the model can be achieved for these categories.

Botswana

Botswana dataset consists of a 145-band hyperspectral scene, 1476 by 256 pixels, in which we can find a natural environment, in which relatively small groups of pixels have been labelled, with 14 different categories such as water, exposed soils, different types of grasses, and so on. Figure 15 shows the complete scene on the left and a zoom in on the right where the size of the labelled areas can be seen.

In this case we performed a different experiment, where we want to show the influence of the noisiness of the labels on the behaviour of our classification model. As explained in the experiments described above, for these satellite scenes we used a moving window that runs through the scene and for each feed generates a sample of the window size. The label of this sample is then defined based on the label value of the pixels it contains. In the previous experiments only samples where all pixels had the same value were considered, except in cases where the categories had too few pixels and therefore this criterion was inapplicable. In the case of this dataset, the idea is precisely to play with this aspect. For this purpose, 4 different sets of samples were generated, based on the following criteria. The entire scene was traversed with a 4x4 pixel window and all possible samples were generated, so that it was possible to determine a category with a majority of pixels in the sample. This total set was then filtered so that all samples had a maximum of m pixels for at least one category. The background was discarded as the majority category, because there are certainly many pixels that spectrally correspond to one of the 14 categories, which can lead to confusion.

It is interesting to see in the results shown in Fig. 16 that regardless of the noise level of the labels of each sample, generated with the moving window, the Overall Accuracy (OA) level is almost the same for all four cases (100%). Interestingly, in the case of \(m=16\), i.e. the one where the labels are less noisy, or rather noiseless, with respect to the labelling process, but not the spectral information, of course, is the only case where there is confusion in the result.

Classification of geometallurgical categories

In this experiment, we test the ability of our approach to classify categories of a higher level of abstraction relative to the physicochemical phenomena that are normally considered in this problem. In our scheme, the latent state \(\textbf{T}\) that allows modelling population identities is flexible and can be used for different tasks (or abstract variables).

In Fig. 17, we present the levels of abstraction used in geometallurgic classification or emergence levels (according to the categories of the theory of systems77), from left (simpler) to right (more complex). At one end, we have geochemistry, where spectral signatures have typically been identified for various elements, such as Cu or Fe, in different spectral ranges. To the right, we have geological categories, such as rock type, alteration type and mineralization, which are emergent phenomena from geochemistry. Further to the right, we have categories associated with the output (pipeline) of the mining process, in which the simpler characteristics of the ore are mixed, resulting from the blasting, loading and haulage processes. Finally, the ore is delivered to three processing lines, each of which takes samples for analysis, precisely those involved in this case study.

Experiment description

Using one of the hyperspectral image sets published in78, specifically the set called “Mineral 1” (see Fig. 18), we performed two classification experiments, based on the approximate inference algorithm described in (4). Each hyperspectral image in the “Mineral 1” dataset has an associated set of labels. For the experiments performed, two of these were used: the grain size of the associated sample and the provenance of the mineral sample. In the first case, the experiment resembles a texture classification task. In the second case, the experiment is the classification of a hidden variable (provenance classification task) associated with the identification of the deposit areas from which the mineral samples contained in each image come.

These are some of the RGB format images provided in78 as a complement to each VNIR hyperspectral image. The colours are false colours and help to visualise ranges with more spectral energy. We can observe different grain profiles and mineral compositions. Not all images have the same size, due to the different amount of mass of the samples.

The hyperspectral data consists of 99 images of mineral samples, which belong to three grain size profile categories (fine, coarse and mixed) and, at the same time, belong to three different mineral flotation processing lines (P1, P2 and P3), as shown in Table 4. Then from the same images, we have two different inference tasks: the size classification task and the provenance classification task.

Each task was performed using all 99 images. In both cases 67 different combinations of train and test sets of images were used, each with a different ratio between the number of images used for each subset (3-96, up to 70-30 respectively). For the size classification task, we use the relationship between a label (fine, coarse, and mixed) and sample characteristics (size distribution) that are fairly obvious, as they have been generated in a physical preparation process using size separation meshes for the different sets of mineral samples. However, in the case of the provenance classification task, our inference method is aggressively tested, since, as shown in Fig. 17, the relationship between the geochemical characteristics of each mineral sample and its provenance is circumstantial. Thus, the causal relationship between the label (provenance) and the underlying physicochemical phenomenon that translates in the spectral information is highly abstract.

Results

As shown in Figs. 19 and 20, in the case of the grain profile variable, 100% classification accuracy was achieved with 28 training samples. In the case of provenance classification, the number of training samples required to achieve 100% accuracy is slightly higher (33). It is interesting to note that both cases are solved using our general framework with excellent results, even though the type of variables (or inference tasks) are quite different. In this sense, it is important to note that our method has the capacity to uncover – in a data-driven way – the causal relationship between the characteristics of the samples and any phenomenon attributed to them.

This flexibility is attributed to the hierarchical nature of our model that can represent and capture complex relationships between causes (explanatory factors) and observations (effects).

Infogram of the sample size classification experiment: (a) shows the classification accuracy as a function of the number of occupied samples for the training set; (b) shows the confusion matrix for the case of 28 training samples; (c) shows the confusion matrix for the case of 4 training samples; and (d) shows examples of the histograms \((\hat{p} (I)\) for each \((\mathcal {I}, \tilde{z}_k)\) in confusion cases, with respect to their hypothesis models \(\tilde{v}_k\).

Infogram of the sample provenance classification experiment: (a) shows the classification accuracy as a function of the number of occupied samples for the training set; (b) shows the confusion matrix for the case of 33 training samples; (c) shows the confusion matrix for the case of 10 training samples; and (d) shows examples of the histograms \((\hat{p} (I)\) for each \((\mathcal {I}, \tilde{z}_k)\) in confusion cases, with respect to their hypothesis models \(\tilde{v}\).

Classification of mineralogical categories

In this experiment, we address a rather more challenging and realistic scenario – considering the issues mentioned in detail in “Introduction”, related to spectroscopic field applications. The database used is published in78 and called “Porphyry”. It consists of 28 mineral samples (two images of each, in each spectral range used) whose compositions and grain profiles were designed in the laboratory. The challenges of classification in this case are a) the small amount of data per category, which rules out deep learning methods; b) the single label each image has, which represents the full complexity of the sample (captured in the image); c) the highly-mixed nature of the samples, which means that each pixel contains mixtures of mineral components and particle sizes; and d) the lack of spectral expression of several of the minerals in the spectral ranges used in the experiment, such that traditional techniques that rely on specific spectral features cannot be applied.

Experiment description

The hyperspectral images in this dataset were acquired from laboratory-mixed mineral samples from twelve relatively pure minerals. Based on the principal components of each mixture, the samples were assembled into eight groups (\(Q_1\) to \(Q_8\)). Table 5 shows the average content of each of the 12 minerals in the samples from each of the groups. For samples within each of the eight groups, the differences in hyperspectral content are less significant, but no sample is the same as another, except that each sample corresponds to two images for each spectral range used.

The experiment consisted of classifying the \(Q_n\) groups using our model. Five different sets of images were used, as shown in the Table 6. The first set corresponds to images taken in the Visual and Near Infrared (VNIR) range, which ranges from a wavelength of 400-1000 nanometres. The next three sets correspond to images in three continuous sub-segments of the previous range, each with the same number of bands (312). Finally, the last set corresponds to the Short Wave Near Infrared (SWIR) range, which ranges from a wavelength of 1000-2500 nanometres. In addition, this last sensor has a higher signal-to-noise level, but with a lower spatial resolution than the VNIR. The aim of using this variety of sensors is to compare the behaviour of our model in different discrimination conditions and to provide corroborating evidence that our framework offers good discrimination beyond the presence or absence of specific spectral features.

In this case, the mixture in each sample is composed of minerals that are expressed with respect to their particular spectral characteristics, in different ranges, according to the widely documented standards of reflectance spectroscopy in minerals. A summary of these standards for the 12 minerals included in the mixtures used is presented in Table 7. It can be verified that for each mineral the situation in the table is different in each spectral range. The designations “No Diag,” “Inferred,” and “Good” convey the following meanings in the context of spectral analysis: “No Diag” denotes the absence of discernible spectral attributes characterizing the mineral within the specified range. “Inferred” suggests the likelihood of a specific mineral presence inferred from prevailing spectral attributes detected within the range, while “Good” signifies the explicit identification of distinctive spectral features within the specified range. A quick cross-check of Tables 5 and 7 confirms that none of the \(Q_n\) groups can be classified by specific spectral characteristics.

The experiment then consisted of classifying into the 5 spectral ranges (VNIR, VNIR 1/3, VNIR 2/3, VNIR 3/3, and SWIR), for different combinations of the following parameters: a) size of the averaging kernel s, b) number of sampled pixels n, and c) the size of the support set b (test set) — as the total number of images in each spectral range is 56, then the size of the training set is \((56 - b)\) in each case. The first 4 columns of Table 8 show the combinations of these parameters included in the experiment. Finally, for the 5 classification tasks, it is important to mention that we used stratified sampling to choose the training set, i.e. we included at least one sample per target set (\(Q_1\)-\(Q_8\)) and approximately the same proportion with respect to the total number of samples per group.

Results

First, leave-one-out validation rounds were performed for each spectral range, with fixed parameters \(s=4\) and \(n=1000\). In this case, the result was 100% correct classification for the 5 spectral sensors. Given this result, a short sensitivity analysis was performed on the parameters s, n and b, to verify under which conditions our model fails. In this way, 17 experiments were performed for each spectral range, using the k-fold method. The results of these experiments are shown in Table 8. For each spectral range used and each combination of parameters used, the following indicators are presented: normalized accuracy (Acc), weighted precision (Prec), and weighted recall (Rec). It can be seen that the cases of confusion in the classification of some images are quite limited, even in experiments where the parameters have been forced to an extreme (e.g. \(n=10\) or \(b=47\)). To illustrate that, Fig. 21 presents two sets of 5 confusion matrices, corresponding to the results of two of the worst cases of the experiments shown in Table 8. The top row corresponds to experiment 1 (\(b=47\)) and the bottom row to experiment 10 (\(n=10\)). In both cases, the number of confusions is quite low.

To dig into the reported confusions presented in Fig. 21, Table 9 shows the mineral contents of each of the samples of groups \(Q_1\) and \(Q_7\) with the most recurrent confusions.

It can be seen that the most important difference between the two groups is the pyrite (Py) content, where the rest of the minerals, including quartz (Qz) and molybdenite (Mb), have more subtle differences in the mixtures. If we look at Table 7, pyrite has no clear spectral expression in any of the ranges, except in the case of the VNIR, where by inference its presence can be identified. However, in the case of experiment 10 (Fig. 21 bottom row), the best behaviour occurs in the SWIR range, which can be explained by the higher signal-to-noise level of the sensor or by the relation between the s parameter of the experiment and the lower spatial resolution of the sensor.

Another interesting aspect to note is that in both experiments (1 and 10) the behaviour of VNIR sub-segments 2 and 3 is very similar, but not that of the first sub-segment. In this case, it can be conjectured that the worse classification behaviour in the VNIR 1/3 range is due to a general decay of the signal in this spectral range, which is a characteristic presented in all samples. This feature could be attributed to the low light reflection of the whole set of all minerals in this range.

RGB image texture classification

As an alternative, we tested our model and learning algorithm in a case where we cannot rely on the depth of spectral information but where our model could still be valid. This is a scenario in which the objective is the classification of RGB texture images (i.e., \(m=3\)). We consider a dataset with 8674 surface texture images, grouped into 64 categories from 3 public datasets – see Fig. 22 for examples of textures in the database that can be accessed here https://github.com/abin24/Textures-Dataset.

We trained on 20% of the dataset, without any specific adaptation of our framework to the task, and we reproduced the experiment presented in79 – where the authors tested 18 deep neural network architectures – for a random subset of categories of 6 classes. Remarkably, we obtained an accuracy of 97.9% – the results in79 are 99.93% (best), 97.02% (worst), 98.93% (average). To complement, Fig. 22 shows the relationship between the inferred hypothesis models and a sample of each of the 6 associated categories. It is worth noting how these models capture the individuality of each texture from the knowledge (presence/absence) presented in the data.

These distributions offer a signature description of each texture identity that can be used to understand the problem and the hidden image formation process of the dataset.

Conclusion

We have presented a novel and disruptive framework for approaching the problem of hyperspectral image analysis and classification that departs from the classical and widely used featured-based approach. It rests on three pillars:

-

1.

A generative latent variable model expressing the hyperspectral image formation process. This model captures the realistic assumption that between the phenomenon (phenomenological identity) and the observations (pixels) there is a hidden layer that groups pixels into meaningful population identities.

-

2.

An approximate inference scheme that is implementable . This offers an effective discrimination of phenomenological identities exploiting the deep nature of hyperspectral images.

-

3.

A semi-supervised learning strategy that learns our generative model using partial and noisy annotations of the phenomenological identities.

Experiments on simulated data, according to the proposed direct latent graphical model, validate the discrimination capability of our framework, showing that both inference and learning schemes are consistent with it. More importantly, experiments with real hyperspectral data showed that our framework is able to achieve 100% accuracy with only 30% of the data poorly annotated at the global level, i.e. without the need to have extensive pixel-by-pixel annotations. Furthermore, we have tested our approach using an extensively studied texture classification task (RGB), achieving 97.9% accuracy without any fine-tuning, which is very close to state-of-the-art results. These results show the ability of our strategy to capture the formation generative process of many image classification tasks and use that knowledge for effective discrimination.

Discussion

It is important to note that the introduction of the hidden layer (which we call \(\textbf{T}\)) in our model has two remarkable consequences:

-

1.

It allows us to infer complex causal factors (variables), which are the mixtures of simpler phenomena from the classical physicochemical and spectroscopic perspective. If we look at this capacity from the perspective of systems theory77, our approach allows us to discriminate categories that are at a higher level of emergence from the characteristics or signatures conventionally considered by spectroscopy experts.

-

2.

It allows inferences to be highly discriminative by exploiting the deep nature of state-of-the-art hyperspectral sensors. Then, our model is capable of inferring phenomena whose pixel-level spectral characteristics are not clearly expressed in the frequency spectral range of the sensor.

However, although it has been shown by Eq. (12), that knowledge of the spectral signature (a priori distribution) is not necessary to perform inference with this method, which is confirmed by the result of the experiment in “Classification of mineralogical categories” (where it turns out that it is possible, with the proposed model, to classify mineralogical species whose spectral characteristics are not in the ranges in which the data are found), it is important to determine how this occurs, which leaves open an important question, which has not been addressed in this work. Beyond the concept of the coined probabilistic spectral signature, from the point of view of the physical phenomenon in which the spectra are generated, it is important to reach well-founded conclusions, since we would be talking about the transfer of information expressed in different energy levels.

Future work

Our inference and learning schemes were designed for image classification. A relevant direction for future work would be to extend our approach to the context of regression problems. Furthermore, we envision the following lines of future work:

-

To study the spectral physical phenomenon behind the fact that a hyperspectral image contains sufficient information, in different spectral sub-ranges, for the model to be able to classify species, whose spectral characteristics, commonly known, are not in any of these ranges.

-

Extend our three-layer latent variable model to richer deep probabilistic structures;

-

Extend the learning scheme to cover the case of fully unsupervised data. This would enable the generation of knowledge from data with a non-specific task at hand;

-

Embed the model (1) in a deep neural network architecture, taking advantage of its similarity to those used in variational autoencoders (VAE);

-

From a hardware implementation point of view, study hyperspectral sensor design strategies that include i.i.d. image generation, along the lines of that proposed in80, to reduce the amount of data that needs to be processed.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the Figshare repository, in the GitHub repository, in the Pardue University repository and in the University of the Basque Country repository: https://springernature.figshare.com/articles/dataset/HIDSAG_Hyperspectral_Image_Database_for_Supervised_Analysis_in_Geometallurgy_-_MINERAL1_data/19726804. https://springernature.figshare.com/articles/dataset/HIDSAG_Hyperspectral_Image_Database_for_Supervised_Analysis_in_Geometallurgy_-_PORPHYRY_data/19726822. https://github.com/abin24/Textures-Dataset. https://purr.purdue.edu/publications/1947/1. https://www.ehu.eus/ccwintco/index.php/Hyperspectral_Remote_Sensing_Scenes. For any information about the data used in this study, please contact Alejandro Ehrenfeld by email at aehrenfeld@alges.cl.

References

James, J. A brief history of spectroscopy 1–5 (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Hunt, R. History of Spectroscopy - an essay. Ph.D. thesis, Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) (2011).

Minardi, S., Harris, R. J. & Labadie, L. Astrophotonics: astronomy and modern optics. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 29, 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00159-021-00134-7 (2021).

Pasquini, C. Near infrared spectroscopy: A mature analytical technique with new perspectives-a review. Analytica Chimica Acta 1026, 8–36 (2018).

Lagalante, A. Atomic absorption spectroscopy: A tutorial review*. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 34(3), 173–189 (2007).

Wang, Q. & Nielsen, U. G. Applications of solid-state nmr spectroscopy in environmental science. Solid State Nuclear Magn. Reson. 110, 101698 (2020).

Theophile, T. Infrared spectroscopy: Materials science, engineering and technology (BoD-Books on Demand, UK, 2012).

Geladi, P., Burger, J. & Lestander, T. Hyperspectral imaging: Calibration problems and solutions. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 72, 209–217 (2004).

Curran, P. & Dungan, J. Estimation of signal-to-noise: A new procedure applied to aviris data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 27, 620–628 (1989).

Burger, J. & Geladi, P. Hyperspectral nir image regression part i: Calibration and correction. J. Chemom. 19, 355–363 (2005).

Vidal, M. & Amigo, J. M. Pre-processing of hyperspectral images. Essential steps before image analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 117, 138–148 (2012).

Egaña, Á. F. et al. A robust stochastic approach to mineral hyperspectral analysis for geometallurgy. J. Min. 10, 1139 (2020).

Raychaudhuri, B. Imaging spectroscopy: Origin and future trends. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 51, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/05704928.2015.1087405 (2016).

Hapke, B. in Reflectance methods and applications Third edition edn, (eds Lindon, J. C., Tranter, G. E. & Koppenaal, D. W.) Encyclopedia of Spectroscopy and Spectrometry (Third Edition) 931–935 (Academic Press, Oxford, 2017). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128032244000194.

Badura, I. & Da̧bski, M. Reflectance spectroscopy in geology and soil sciences: Literature review. Quaest. Geogr. 41, 157–167. https://doi.org/10.2478/quageo-2022-0031 (2022).

Amigo, J. M., Babamoradi, H. & Elcoroaristizabal, S. Hyperspectral image analysis. A tutorial. Analytica Chimica Acta 896, 34–51 (2015).

Torres, I. & Amigo, J. M. in Chapter 2.8 - an overview of regression methods in hyperspectral and multispectral imaging (ed.Amigo, J. M.) Hyperspectral Imaging, Vol. 32 of Data Handling in Science and Technology 205–230 (Elsevier, 2019). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444639776000109.

Khan, M. J., Khan, H. S., Yousaf, A., Khurshid, K. & Abbas, A. Modern trends in hyperspectral image analysis: A review. IEEE Access 6, 14118–14129 (2018).

Saha, D. & Manickavasagan, A. Machine learning techniques for analysis of hyperspectral images to determine quality of food products: A review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 4, 28–44 (2021).

Grewal, R., Singh Kasana, S. & Kasana, G. Machine learning and deep learning techniques for spectral spatial classification of hyperspectral images: A comprehensive survey. Electronics 12, 488 (2023).

Zhang, T., Fu, Y. & Zhang, J. Guided hyperspectral image denoising with realistic data. Int. J. Comput. Vision 130, 2885–2901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-022-01660-2 (2022).

Hu, Z. & Zhang, Y. Effect of dimensionality reduction and noise reduction on hyperspectral recognition during incubation period of tomato early blight. Guang Pu Xue Yu Guang Pu Fen Xi/Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 43, 744–752 (2023).