Abstract

Intracranial vessel wall imaging (VWI), which requires both high spatial resolution and high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), is an ideal candidate for deep learning (DL)-based image quality improvement. Conventional VWI (Conv-VWI, voxel size 0.51 × 0.51 × 0.45 mm3) and denoised super-resolution DL-VWI (0.28 × 0.28 × 0.45 mm3) of 117 patients were analyzed in this retrospective study. Quality of the images were compared qualitatively and quantitatively. Diagnostic performance for identifying potentially culprit atherosclerotic plaques, using lesion enhancement and presence of intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH), was evaluated. DL-VWI significantly outperformed Conv-VWI in all image quality ratings (all P < .001). DL-VWI demonstrated higher SNR and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) than Conv-VWI, both in normal walls (basilar artery; SNR 4.83 ± 1.23 vs. 3.02 ± 0.59, P < .001) and lesions (contrast-enhanced images; SNR 22.12 ± 11.68 vs. 8.33 ± 3.26, P < .001). In the assessment of 86 lesions, DL-VWI showed higher confidence of detection (4.56 ± 0.55 vs. 2.62 ± 0.77, P < .001), more concordant IPH characterization (Cohen’s Kappa 0.85 vs. 0.59) and greater enhancement. For culprit plaque identification, IPH exhibited higher sensitivity in DL-VWI compared to Conv-VWI (70.6% vs. 23.5%) and excellent specificity (94.3% vs. 94.3%). Deep learning application of intracranial vessel wall images successfully improved the quality and resolution of the images. This aided in detecting vessel wall lesions and intraplaque hemorrhage, and in identifying potentially culprit atherosclerotic plaques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAD) is one of the most common causes of ischemic stroke, and serves as an important indication for the intracranial vessel wall imaging (VWI)1. The currently recommended VWI protocol in ICAD patients includes 3D T1-weighted images (T1WI) with and without contrast-enhancement2, which can detect imaging features of the culprit atherosclerotic plaques, such as contrast enhancement and intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH)1,3,4. However, due to the practical limitation of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in VWI, it is often challenging to identify these features or even detect the lesion itself, especially in small distal arteries5,6. Considering the size of intracranial arteries and the pathologic lesions, the recommended VWI protocols require both submillimeter in-plane resolution and sufficient SNR within a clinically acceptable scan time5,6. Many acceleration techniques, such as parallel imaging and compressed sensing, have been applied in VWI to achieve this goal5,7,8,9. Nevertheless, obtaining VWI with desirable image quality remains a challenging task.

Recently, image quality improvement of MRI is a promising application for deep learning (DL) in radiology10. VWI is an ideal candidate for DL-based image quality improvements, and a few studies have considered the benefit of DL-based noise reduction of VWI11,12. Meanwhile, super-resolution is another approach for image quality improvement that is commonly used in nonmedical images13. As recent reports have suggested the use of DL-based super-resolution on brain and neurovascular MRI14,15, super-resolution would be another well-suited method for improving the image quality of VWI.

In this study, we hypothesize that the improvement of image quality and resolution can increase the clinical value of VWI, particularly for the detection and characterization of small vessel wall lesions. To achieve this goal, we employed a DL-based method that simultaneously performs super-resolution and noise reduction on VWI. The purpose of this study is to assess the image quality of DL-augmented intracranial VWI and to explore the clinical value of the proposed method in detection and characterization of vessel wall lesions.

Methods

Study subjects

The institutional review board of The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine (KC22RISI0764), approved this single-center study and waived the requirement for informed consent due to its retrospective nature. The entire process of the research was performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki, and with relevant guidelines and regulations of our Institutional Ethics Committee.

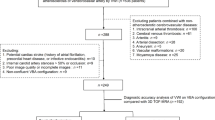

A total of 143 patients underwent MRI with a high-resolution VWI protocol from January to July 2022 at our institution. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) deviant VWI protocols (n = 26) and (2) loss of unprocessed DICOM images (n = 0). Clinical parameters, including age, sex, indication of the VWI, presence of acute and chronic ischemic lesions, and cerebrovascular risk factors, were recorded. For the participants with acute ischemic strokes, we also collected the date of the image-confirmed infarct.

MRI protocols

All MRI examinations were performed on one of four 3.0-T scanners (MAGNETOM Vida; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with 64-channel coils. The protocol for acquiring VWI included acquisition of 3D turbo spin-echo T1WI with and without contrast enhancement and proton density images (PDI). Oblique coronal scans were performed to cover the circle of Willis and both carotid bifurcations at once. Both sequences were scanned with voxel size of 0.51 × 0.51 × 0.45 mm3 within 6 min. Further detailed scan parameters are provided in Supplemental Materials. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (CE-T1WI) were acquired 4 min after intravenous infusion of gadolinium-based contrast media with the same protocol as nonenhanced T1-weighted images (NE-T1WI).

Deep learning-based image quality improvement

This study utilized SwiftMR v2.2.0.0 (AIRS Medical, Seoul, Korea)16, an MR image reconstruction software incorporating a deep neural network (DNN) based on the U-Net architecture17. The model includes 18 convolutional blocks complemented by layers for max-pooling, up-sampling, and feature concatenation, culminating in three convolutional layers. This design aims to improve spatial resolution and contrast while minimizing noise.

In generating the training inputs, k-space sampling patterns were applied through multi-dimensional degradation of k-space data. Various undersampling patterns (uniform, random, kmax, partial Fourier, and elliptical) and noise addition were simulated and incorporated. Auxiliary contextual data, defining k-space sampling and expected noise reduction ratios, were prepared to assist the network in handling diverse learning tasks. To effectively utilize this auxiliary input, the U-Net architecture was modified to include a dynamic modulation pathway, resulting in a context-enhanced U-Net (CE U-Net).

L1-loss ensured reconstructed images closely matched high-resolution reference images and maintained anatomical precision. The learning rate, initially set at 0.001, was reduced by a factor of 0.1 after 10 epochs, followed by 3 additional epochs of training. The model was optimized using Adam18 and four GPUs (Tesla V100, NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), each with 32 GB of memory. The training and validation datasets included approximately 3 million image slices (1 million 2D slices and 2 million 3D slices), covering a broad range of MR imaging sequences, anatomical locations, and imaging parameters.

Vessel wall images were part of both training and validation datasets described above, and they are mutually exclusive from the dataset used during this study to maintain the study’s analytical validity. The trained model transforms conventional vessel wall images (Conv-VWI) into deep learning-augmented vessel wall images (DL-VWI) by performing super-resolution (0.28 × 0.28 × 0.45 mm3) and noise reduction (Fig. 1).

An example of DL-based image quality improvement on nonenhanced T1-weighted VWI. Conv-VWI (A) displays acceptable image quality and good wall-to-lumen contrast. DL-VWI (B) show excellent suppression of noise with well-preserved contrast. Especially, vessel walls are more clearly visualized on DL-VWI than on Conv-VWI (magnified views, bifurcation of internal carotid arteries).

Image quality and vessel wall lesion assessments

Two neuroradiologists (with 18 and 7 years of experience, respectively) independently assessed overall image quality, visually perceived SNR, conspicuity of vessels, and degree of artifacts, in nonenhanced T1-weighted Conv-VWI and DL-VWI. The four parameters were rated on a 5-grade Likert scale (Supplemental Table 1). We referred to the image quality evaluation method from a previous study with our modifications9.

The two reviewers also independently assessed every delineable vessel wall lesion, regarding the features of confidence of detection, conspicuity, presence of IPH, and contrast enhancement (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table 1). IPH was considered present when a plaque exhibited a focal or segmental region with precontrast T1WI hyperintensity (> 150% of the normal wall) within the eccentric thickened wall lesion1,4. Lesion enhancement was scored as 0 (none), 1 (less than the pituitary stalk) and 2 (equal to or greater than the pituitary stalk); based on previous studies, only score 2 was considered positive for plaque classification1,19,20,21. The images were randomly divided into two complementary sets, each consisting of either Conv-VWI or DL-VWI per patient. Both reviewers were blinded to the patient order and the types of randomly shuffled images. A four-week interval was maintained between the assessments of the two image sets to avoid recall bias.

Quantitative image quality assessment was based on a 3D semiautomatic segmentation of the normal vessel walls and lumens of the 1st segments of the middle cerebral arteries (M1s) and basilar arteries (BAs) in NE-T1WI, supported by PDI (Fig. 3). During the SNR and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) calculation, noise was measured in the vessel lumen. All measured values were normalized across subjects based on the reference tissue (central pons). The same procedure was performed for the included vessel wall lesions, both in NE-T1WI and CE-T1WI (Fig. 3). The entire assessment was performed using dedicated software (3D Slicer, version 5.0.3, http://slicer.org) by an experienced neuroradiologist, and the further detailed methods are provided in Supplemental Materials.

An example of the segmentation process for the vessel wall, lumen, and vessel wall lesions. After coregistration of NE-T1WI (A, B) and PDI (C), the regions of interest for a normal vessel wall and lumen are drawn semiautomatically (outer margin, yellow; inner margin, orange). The region of interest for a delineable middle cerebral arterial wall lesion is shaded in yellow on NE-T1WI (D, E) and CE-T1WI (F).

Atherosclerotic plaque classification

The reference standard was determined after completing the entire image analysis procedure, which was blinded to the previous image analysis. All detected atherosclerotic plaques were deliberately classified by the consensus of two experienced neuroradiologists into potentially culprit and nonculprit plaques. A plaque was considered potentially culprit if it met one of the following criteria: (a) it was the only lesion or (b) it was the most stenotic lesion in the vascular territory associated with a concurrent image-proven acute ischemic stroke1,19,20. All plaques located in other vascular territories, and the indeterminate plaques other than the most stenotic lesion within the stroke vascular territory, were regarded as nonculprit plaques. The presence and accurate location of these lesions were confirmed by consensus between two neuroradiologists, using not only Conv-VWI and DL-VWI but also all other available clinical information and radiologic modalities, including MR, CT or digital subtraction angiographies.

Statistical analysis

The clinical characteristics of the patients are provided as descriptive statistics. Cohen’s quadratically weighted Kappa coefficients (κ) were calculated based on the quality ratings of the two reviewers. The criteria of Landis and Koch were used to interpret these values, with κ values of 0.00–0.20, 0.21–0.40, 0.41–0.60, 0.61–0.80, and 0.81–1.00 indicating slight, fair, moderate, substantial, and almost perfect agreement, respectively22. The Conv-VWI and DL-VWI scores were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Values of the quantitative assessment, i.e., SNR, CNR, normalized mean signal intensity (SI) and standard deviation (SD) of vessel walls, lumens and lesions were compared with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test or paired t-test, according to their normality of distribution. The diagnostic performance of plaque enhancement and IPH in identifying potentially culprit plaques was assessed using sensitivity, specificity and area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC). Differences between the AUROCs of Conv-VWI and DL-VWI were compared using DeLong’s test. All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 4.0.3; R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Subject characteristics

A total of 117 eligible patients were included in our study, and their overall clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Among the eligible patients, 15 patients showed markedly degraded images in the vessel wall segmentation step and were excluded from the subsequent quantitative analysis (Supplemental Fig. 1). The most frequent indication on VWI was workup for acute ischemic stroke (74/117, 63.2%), followed by assessment of steno-occlusive intracranial arterial lesions (23/117, 19.7%) and suspicion of dissection (11/117, 9.4%). Approximately two-thirds of the patients had acute infarcts, with a mean interval of 5.41 days (range: 1–21 days) between the image-confirmed infarct and VWI.

A total of 86 vessel wall lesions were delineated from the VWI of 56 patients. Among them, 70 lesions were atherosclerotic plaques, and 11 lesions were suspected to be dissections. Four lesions from 4 patients were excluded in lesion assessment using CE-T1WI due to lack of contrast-enhanced images.

Image quality and vessel wall lesion assessments

Table 2 displays the results of the image quality and lesion assessments. Overall image quality (4.18 ± 0.72 vs. 2.94 ± 0.62), visual SNR (4.32 ± 0.68 vs. 2.59 ± 0.55) and vessel wall conspicuity (4.26 ± 0.69 vs. 3.12 ± 0.65) were significantly higher in DL-VWI than in Conv-VWI. While the interrater agreement was fair to substantial for both Conv-VWI and DL-VWI, it was generally higher in DL-VWI than in Conv-VWI (Table 2).

In the vessel wall lesion assessment, confidence of detection (4.54 ± 0.56 vs. 2.59 ± 0.79) and conspicuity (4.30 ± 0.67 vs. 3.00 ± 0.83) were significantly higher in DL-VWI compared to Conv-VWI with moderate to substantial agreement. The two reviewers made more concordant judgments (discordant results 5 vs. 11; Kappa 0.85 vs. 0.59) and reported a higher presence of IPH (19 vs. 11) in DL-VWI compared to Conv-VWI. The visual degree of lesion enhancement was slightly but significantly higher in DL-VWI (1.40 ± 0.65 vs. 1.26 ± 0.76) with substantial to almost perfect interrater agreement.

On quantitative analysis the SNR and CNR of normal vessel walls in DL-VWI were significantly higher than those in Conv-VWI (SNR M1 4.04 ± 1.05 vs. 3.38 ± 0.81, BA 4.83 ± 1.23 vs. 3.02 ± 0.59; CNR M1 2.21 ± 0.83 vs. 2.00 ± 0.75, BA 1.80 ± 0.75 vs. 1.32 ± 0.53), and this difference was larger in BAs than M1s (Supplemental Fig. 2). The decrease of SD in DL-VWI, which represents decreased image noise, was more prominent in the central area of images (BA) than in their periphery (M1) (Supplemental Table 2).

The vessel wall lesions demonstrated significantly higher SNR and CNR in DL-VWI compared to Conv-VWI, both in CE-T1WI (SNR 22.04 ± 11.62 vs. 8.30 ± 3.25, CNR 16.67 ± 11.05 vs. 6.49 ± 3.27) and NE-T1WI (SNR 7.56 ± 3.15 vs. 4.76 ± 1.34, CNR 4.68 ± 2.60 vs. 3.05 ± 1.26, Supplemental Fig. 3). The lesions in CE-T1WI demonstrated slightly but significantly higher SI in DL-VWI (Supplemental Table 2), in line with the qualitative lesion assessment. The decrease of SD in wall lesions was weaker compared to normal vessel walls and lumens, especially in CE-T1WI (normal walls and lumens, all P < 0.001; lesions in CE-T1WI, P = 0.10; Supplemental Table 2). Notably, culprit plaques in CE-T1WI showed slightly higher SD in DL-VWI than in Conv-VWI (44.13 ± 12.43 vs. 42.44 ± 10.66), but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.10).

Atherosclerotic plaque classification using VWI

The diagnostic performance of Conv-VWI and DL-VWI in plaque classification is demonstrated in Table 3. Plaque enhancement showed similar sensitivity (88.2% vs. 88.2%) and specificity (83.7% vs. 81.6%) between Conv-VWI and DL-VWI (AUROC 0.86 vs. 0.85, P = 0.32). IPH exhibited only 23.5% sensitivity in Conv-VWI, which has significantly increased to 70.6% in DL-VWI, while maintaining excellent specificity in both VWIs (94.3% and 94.3%, respectively). DL-VWI was significantly better for detection of potentially culprit plaque using IPH (AUROC 0.59 vs. 0.82). When combination of enhancement and IPH was used for culprit plaque classification, DL-VWI showed higher AUROC (0.91; sensitivity 100%, specificity 81.6%) in diagnosing culprit plaques than Conv-VWI (0.84; sensitivity 88.2%, specificity 79.6%), with marginal significance (P = 0.10).

Representative cases

Figure 4 demonstrates better depiction of the culprit plaque characteristics on DL-VWI. DL-VWI was also helpful in detecting subtle plaque enhancement (Fig. 5) and lesions in severely motion-degraded images (Supplemental Fig. 4). Identification of dissection, especially differentiating it from atherosclerosis, was more confidently performed when nonenhanced and contrast-enhanced DL-VWI were available (Supplemental Figs. 5, 6). Another example culprit lesion containing IPH was used to measure signal profiles, both on NE-T1WI and CE-T1WI (Fig. 6).

Two illustrative cases of potentially culprit plaques. (A) In a 62-year-old male with abrupt dysarthria and pontine infarct, only mild distal basilar stenosis was identified on MR angiography. (B) Conv-VWI revealed the plaque with punctate T1WI hyperintensity, which was interpreted as an intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH) by only one reviewer. (C) DL-VWI more clearly depicts the apparent T1WI hyperintensity and positive remodeling. (D) Another 66-year-old male presented with abrupt left homonymous hemianopia, showing right posterior cerebral artery territory infarct with focal distal stenosis. (E) Same as Fig. 1, the signal of the plaque in Conv-VWI was misinterpreted as image noise by both reviewers. (F) DL-VWI provides a clearer depiction of the presence of IPH.

A 71-year-old female with a segmental atherosclerotic plaque along the 1st segment of the left middle cerebral artery. The shape of the wall lesion is more clearly delineated in DL-VWI (D–F) than in Conv-VWI (A–C). In contrast-enhanced Conv-VWI (B and C), contrast enhancement is not clearly seen due to the background noise of the vessel wall and brain parenchyma. However, contrast-enhanced DL-VWI (E and F) clearly depict subtle enhancement at the distal portion of the wall lesion.

An example of a potentially culprit vessel wall lesion containing intraplaque hemorrhage. The signal profile is measured using both Conv-VWI (A, NE-T1WI; D, CE-T1WI) and DL-VWI (B, NE-T1WI; E, CE-T1WI). Both signal peaks from the normal vessel wall and the lesion are of similar height when comparing nonenhanced Conv-VWI and DL-VWI (C). On the other hand, contrast-enhanced images display a slightly higher signal intensity peak in DL-VWI compared to Conv-VWI (F). Note that the background noise signal variation is more flattened in DL-VWI, both in nonenhanced (C) and contrast-enhanced images (F).

Discussion

This study demonstrated the clinical value of deep learning-based noise reduction and super-resolution for improving the image quality of intracranial vessel wall imaging. The deep learning-based approach simultaneously improved image quality and spatial resolution, which was feasible and useful for the clinical evaluation of vessel walls. This assisted in detecting vessel wall lesions and identifying potentially culprit plaques, particularly by better characterizing intraplaque hemorrhage.

Prior approaches to acquire VWI with acceleration techniques were practically limited in terms of the acceleration factor that can be achieved while maintaining image quality7,8,9. For example, to attain DL-VWI resolution (0.28 × 0.28 × 0.45 mm3) using conventional acceleration while minimally preserving SNR (similar as Conv-VWI), it requires at least a fourfold increase in acquisition time (24 min) compared to the current protocol, which is not practical in most clinical circumstances. DL-based approaches can resolve this clinical dilemma. Another benefit of our approach is that direct application is possible without any specialized or dedicated method for acquisition or reconstruction. As shown by our results, DL-based image quality improvement can be successfully incorporated into MR images already obtained with conventional acceleration techniques.

Many reports have explored the value of DL-based MRI quality improvement for imaging of various body parts, mostly focusing on noise reduction11,12,23,24,25,26. Meanwhile, there have been reports regarding the potential of DL-based super-resolution processing for MRI14,15,27,28. In this study, we applied a model that performs both denoising and super-resolution simultaneously. This allows seamless integration of the two competing goals for VWI, aiming to achieve the recommended “ideal” resolution near the histologically suggested normal vessel wall thickness while retaining excellent image quality5. Compared to the pilot study, which used same quality ratings12, even a slight decrease in voxel size (0.56 × 0.56 × 0.5 mm3 vs. 0.51 × 0.51 × 0.45 mm3) largely degraded the visually rated SNR of the original images (3.5 vs. 2.59). The combination of DL-based denoising and super-resolution effectively compensated for the threefold decrease in voxel size (0.28 × 0.28 × 0.45 mm3), resulting in high SNR in both qualitative and quantitative assessments.

We demonstrated the clinical feasibility of DL-VWI in detecting potentially culprit plaques, aided by better identification of the IPH and contrast enhancement. In previous reports, IPH generally showed a low sensitivity (12.1‒49.5%) but high specificity (66.7‒98.3%) in detecting culprit plaques1,4,21,29,30, more similar to Conv-VWI in our results. Our DL-VWI identified an additional 8 potentially culprit plaques (47.1% out of 17 plaques; Table 3) containing IPH that Conv-VWI did not detect properly, while maintaining excellent specificity. Meanwhile, plaque enhancement was not significantly different between Conv-VWI and DL-VWI for culprit plaque detection. Similar to our results, previous studies reported a high prevalence of grade 2 enhancement among culprit plaques (50.0‒92.3%), suggesting high diagnostic sensitivity1,19,21,29,31. Our study presents that DL-VWI could be particularly beneficial for culprit lesion detection in patients unable to use contrast materials. It should also be emphasized that detection and delineation of the lesion itself were more confidently performed in nonenhanced DL-VWI.

DL-VWI better revealed the presence of IPH, despite a slightly lower precontrast mean SI of potentially culprit plaques compared to Conv-VWI (88.13 ± 20.37 vs. 89.14 ± 18.49, P < 0.001, Supplemental Table 2). In Fig. 6, the SI of the normal vessel wall and the lesion did not substantially increase in nonenhanced images. Instead, signal variation from background noise was more suppressed in DL-VWI, resulting in better contrast between the lesion and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). On the other hand, the intrinsic signal heterogeneity of the culprit plaques, caused by various internal components32 and presented as higher SD than other lesions, was retained after DL-based denoising (Supplemental Table 2). We speculate that the DL-based image transformation may preserve the true heterogeneous appearance of culprit plaques, such as IPH, making them more noticeable (Fig. 5).

Interestingly, CE-T1WI showed slightly but significantly higher lesion enhancement in DL-VWI, both qualitatively and quantitatively. These findings address the concerns raised by a prior meta-analysis regarding the reduced visibility of small enhancing lesions in high-resolution images due to decreased partial volume effect3. DL-based processing might be a practical solution for this issue, which suppresses undesired background noise while preserving the true enhancement signal (Fig. 6). However, this increased enhancement did not improve the diagnostic performance of DL-VWI in plaque characterization significantly. More than three-quarters of potentially culprit plaques already displayed strong enhancement in Conv-VWI, indicating that the clinical benefit of DL-VWI for detecting contrast enhancement was not remarkable.

There are a few points that should be kept in mind for the clinical application of DL-VWI. Although the DL-based approach is a black box and cannot be fully understood, there were some findings that may imply signal referencing from adjacent structures. For example, a slight increase in lumen SI might be affected by the features of the adjacent vessel walls. Lower SI of the normal BA walls in DL-VWI could be associated with surrounding CSF and susceptibility-related signal loss of the skull base, whereas M1 walls, which are more frequently adjacent to gray matter, showed higher SI in DL-VWI (Supplemental Table 2). Quantitative signal increase of the lesions in contrast-enhanced DL-VWI may also be explained by this signal referencing (Fig. 6). Although this phenomenon may accentuate some signal characteristics of input images, it has not produced false positive lesions based on the observation of this study. However, further evaluation is required in real-world settings, especially for the lesions in images involving tiny structures and subtle signal changes such as VWI.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective study with a limited number of patients. The reference standard was not pathologically proven, so indeterminate lesions less stenotic than the culprit plaque were assumed to be nonculprit to avoid excluding them or designating two culprits for one infarct territory, thereby minimizing selection bias. Owing to the clinically unfeasible acquisition time as mentioned above, the reference standard scans not utilizing DL for super-resolution images could not be obtained for each patient. Additionally, during the quality rating, radiologists may have recognized apparent quality differences in some images even after shuffling, constituting a failure of image type blinding and prevention of observer bias. Coregistration of the images for quantitative measures may not be perfect in some cases, since normal vessel walls are extremely thin and misregistration of a single voxel may cause partially inadequate segmentation. Finally, SNR was calculated only on a single clinical scan per patient, which might lead to errors for images with parallel imaging.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the application of deep learning-based noise reduction and super-resolution to intracranial VWI successfully improved the quality and spatial resolution of the images. Deep learning-augmented VWI led to increased detection of the vessel wall lesions and intraplaque hemorrhage compared to conventional VWI, suggesting its clinical feasibility in identifying potentially culprit plaques.

Data availability

The data analyzed during the current study are not publicly available owing to internal data transfer policies but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- VWI:

-

Vessel wall imaging

- ICAD:

-

Intracranial atherosclerotic disease

- SNR:

-

Signal-to-noise ratio

- CNR:

-

Contrast-to-noise ratio

- NE-T1WI:

-

Nonenhanced T1-weighted images

- CE-T1WI:

-

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images

- Conv-VWI:

-

Conventional vessel wall images

- DL-VWI:

-

Deep learning-augmented vessel wall images

- M1:

-

1st segment of the middle cerebral artery

- BA:

-

Basilar artery

- IPH:

-

Intraplaque hemorrhage

References

Wu, F. et al. Differential features of culprit intracranial atherosclerotic lesions: A whole-brain vessel wall imaging study in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, 1 (2018).

Song, J. W. et al. MR intracranial vessel wall imaging: A systematic review. J. Neuroimag. 30, 428–442 (2020).

Song, J. W. et al. Vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers of symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis: A meta-analysis. Stroke 52, 193–202 (2021).

Zhu, C. et al. Clinical significance of intraplaque hemorrhage in low- and high-grade basilar artery stenosis on high-resolution MRI. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 39, 1286–1292 (2018).

Lindenholz, A., van der Kolk, A. G., Zwanenburg, J. J. M. & Hendrikse, J. The use and pitfalls of intracranial vessel wall imaging: How we do it. Radiology 286, 12–28 (2018).

Mandell, D. M. et al. Intracranial vessel wall MRI: Principles and expert consensus recommendations of the american society of neuroradiology. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 38, 218–229 (2017).

Jia, S. et al. Joint intracranial and carotid vessel wall imaging in 5 minutes using compressed sensing accelerated DANTE-SPACE. Eur. Radiol. 30, 119–127 (2020).

Suh, C. H., Jung, S. C., Lee, H. B. & Cho, S. J. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging using compressed sensing for intracranial and extracranial arteries: Comparison with conventional parallel imaging. Kor. J. Radiol. 20, 487–497 (2019).

Sannananja, B. et al. Image-quality assessment of 3D intracranial vessel wall MRI using DANTE or DANTE-CAIPI for blood suppression and imaging acceleration. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 43, 837–843 (2022).

Lui, Y. W. et al. Artificial intelligence in neuroradiology: Current status and future directions. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 41, E52–E59 (2020).

Eun, D. I. et al. Deep-learning-based image quality enhancement of compressed sensing magnetic resonance imaging of vessel wall: Comparison of self-supervised and unsupervised approaches. Sci. Rep. 10, 13950 (2020).

Jung, W. et al. MR-self Noise2Noise: Self-supervised deep learning-based image quality improvement of submillimeter resolution 3D MR images. Eur. Radiol. 33, 2686–2698 (2023).

Glasner, D., Bagon, S. & Irani, M. Super-resolution from a single image in 2009 IEEE 12th international conference on computer vision 349–356 (IEEE, 2009).

Rudie, J. D. et al. Clinical assessment of deep learning-based super-resolution for 3D volumetric brain MRI. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 4, e210059 (2022).

Koktzoglou, I., Huang, R., Ankenbrandt, W. J., Walker, M. T. & Edelman, R. R. Super-resolution head and neck MRA using deep machine learning. Magn. Reson. Med. 86, 335–345 (2021).

Jeong, G., Kim, H., Yang, J., Jang, K. & Kim, J. All-in-One Deep Learning Framework for MR Image Reconstruction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.03684 (2024).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation in Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5–9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Qiao, Y. et al. Intracranial plaque enhancement in patients with cerebrovascular events on high-spatial-resolution MR images. Radiology 271, 534–542 (2014).

Sanchez, S. et al. 3D enhancement color maps in the characterization of intracranial atherosclerotic plaques. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 43, 1252–1258 (2022).

Lu, S. S. et al. MRI of plaque characteristics and relationship with downstream perfusion and cerebral infarction in patients with symptomatic middle cerebral artery stenosis. J. Magn. Reson. Imag. 48, 66–73 (2018).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174 (1977).

Kim, M. et al. Thin-slice pituitary MRI with deep learning-based reconstruction: Diagnostic performance in a postoperative setting. Radiology 298, 114–122 (2021).

Chen, F. et al. Variable-density single-shot fast spin-echo MRI with deep learning reconstruction by using variational networks. Radiology 1, 180445 (2018).

Ueda, T. et al. Deep learning reconstruction of diffusion-weighted MRI improves image quality for prostatic imaging. Radiology 303, 373–381 (2022).

Hahn, S. et al. Image quality and diagnostic performance of accelerated shoulder MRI With deep learning-based reconstruction. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 218, 506–516 (2022).

Iglesias, J. E. et al. Quantitative brain morphometry of portable low-field-strength mri using super-resolution machine learning. Radiology 306, e220522 (2023).

Almansour, H. et al. Deep learning-based superresolution reconstruction for upper abdominal magnetic resonance imaging: An analysis of image quality, diagnostic confidence, and lesion conspicuity. Invest. Radiol. 56, 509–516 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. incremental value of plaque enhancement in patients with moderate or severe basilar artery stenosis: 3.0 T high-resolution magnetic resonance study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 4281629 (2017).

Lin, X. et al. Follow-up assessment of atherosclerotic plaques in acute ischemic stroke patients using high-resolution vessel wall MR imaging. Neuroradiology 64, 2257–2266 (2022).

Kwee, R. M., Qiao, Y., Liu, L., Zeiler, S. R. & Wasserman, B. A. Temporal course and implications of intracranial atherosclerotic plaque enhancement on high-resolution vessel wall MRI. Neuroradiology 61, 651–657 (2019).

Shi, Z. et al. Quantitative Histogram Analysis on Intracranial Atherosclerotic Plaques: A High-Resolution Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Stroke 51, 2161–2169 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Nuri-light Radiological Medicine Research Society.

Funding

National Research Foundation of Korea, RS-2023-00208409.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S., W. J., and J.J.: designing the study. M.S., I.S., J.J. L., and J.J.: data collection and literature search. W. J,, G.J., and S.Y.: image processing. M. S. and J. J.: data analysis and interpretation. M. S. and J. J.: drafting the manuscript. All authors have approved the final draft submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Woojin Jung, Geunu Jeong, and Seungwook Yang are employees of AIRS medical. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seo, M., Jung, W., Jeong, G. et al. Deep learning improves quality of intracranial vessel wall MRI for better characterization of potentially culprit plaques. Sci Rep 14, 18983 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69750-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69750-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A multinational study of deep learning-based image enhancement for multiparametric glioma MRI

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Deep learning-based image enhancement for improved black blood imaging in brain metastasis

European Radiology (2025)