Abstract

Desmodesmus spp. are one of the most dominant components of phytoplankton, which are present in most water bodies. However, identification of the species based only on morphological data is challenging. The aim of the present study was to provide a comprehensive understanding of the actual distribution of the Desmodesmus species in Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan. In the present study, 38 water bodies were surveyed between June 2017 and March 2023. A total of 86 culture strains were established from the samples collected from the 21 sites, and identified by molecular phylogenetic analysis, comparison of ITS2 rRNA secondary structures, and observation of surface microstructure. In total, four new species, including D. notatus Demura sp. nov., D. lamellatus Demura sp. nov., D. fragilis Demura sp. nov., and D. reticulatus Demura sp. nov. were proposed and 17 Desmodesmus species were identified as described species. The present study revealed > 20 Desmodesmus species, exhibiting high genetic diversity in a small area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Desmodesmus (R. Chodat) S. S. An, T. Friedl & E. Hegewald (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) is a green algal genus observed in most freshwater areas1,2,3. It is phytoplankton of approximately 10–50 μm. The morphology of Desmodesmus is mostly a colony (coenobium) of four cells in a row with a characteristic structure called “spine” at the edge of the outer cells4,5. However, the spine may be absent in certain species6 or present in all cells of the colony7. In recent years, because of the rapid growth and easy cultivation of Desmudesmus, research on algal mass cultivation that combines the removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater with algal biomass production has increased8,9.

Desmodesmus was an established genus, independent of Scenedesmus by An et al.10.

Scenedesmus is a genus described nearly 200 years ago11, and many species have been described only by morphological information. An et al.10 performed a detailed analysis based on molecular phylogenetic and secondary structure analysis using internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) sequences and showed that Desmodesmus is an independent genus from Scenedesmus.

Desmodesmus exhibits high morphological variation depending on environmental conditions12,13,14; therefore, descriptions based solely on optical microscopic morphological information led to numerous synonyms being attributed to it. However, since the study performed by An et al.10, Hegewald et al. have facilitated the accurate and efficient identification by utilizing a method that combined molecular phylogenetic analysis using ITS2 sequences, ITS2 RNA secondary structure analysis, and detailed morphological observations using scanning electron microscopy (SEM)[e.g., Refs.7,10,15,16]. In the secondary structure analysis of ITS2 RNA, the compensatory base change (CBC) has been proven to be an important character. The CBC is a base mutation that occurs in both nucleotides in a paired structural position, whereas the hemi-CBC is a mutation of a single nucleotide in a paired structural position, in which the nucleotide bond is retained17. The CBC and hemi-CBC, which are predicted from the sequence of ITS2 RNA, have enabled classification that considers the biological species concept17. The CBC and hemi-CBC have been used for taxonomic systematics and identification in microalgae other than Desmodesmus, such as Chlorophyceae17,18 and diatoms19. Nguyen et al.20 have utilized specific sequences ITS2 RNA, considering CBC and hemi-CBC, for the identification of Desmodesmus.

Currently, distributional studies of Desmodesmus species, based on phylogenetic analysis and detailed morphological observation using SEM, are underway in various locations, including Romania21, New Zealand22, and Poland23.

In Japan, Desmodesmus (recorded as Scenedesmus at the time) has been documented as a major phytoplankton genus in many lakes and marshes since the 1930s24,25. However, these studies only reported morphological observations using optical microscopy, and the exact distribution of the species remained unclear. Demura et al.26 were the first to clarify the distribution of Desmodesmus species in Japan by utilizing a method that combined molecular phylogenetic analysis using ITS2 sequences, ITS2 RNA secondary structure analysis, and detailed morphological observations using SEM. Demura et al.26 identified seven previously described species and one new species of Desmodesmus in five water bodies in Saga City, Japan.

Saga University and Saga City office are promoting a microalgae biomass production project and have focused on rapidly-growing Desmodesmus as a target microalgae. The search for Desmodesmus culture strains that could propagate faster was necessary, and a diversity survey of Desmodesmus in lakes and ponds in the city has been conducted. However, Demura et al.26 surveyed only five water bodies, which is insufficient for comprehensively understanding the diversity and distribution of Desmodesmus in Saga City, Japan. Therefore, in this study, I aimed to provide a more detailed understanding of the actual distribution of the Desmodesmus species in Saga City, Japan, and determine the true diversity of Desmodesmus by expanding the study area within Saga City, and increasing the number of analyzed strains.

Results

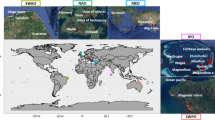

Distribution surveys were conducted across 38 water bodies in Saga City, from June 2017 to March 2023. Desmodesmus species were observed at 21 sites (55.3%) (Fig. 1). In total, 86 Desmodesmus strains were established (Table 1, Fig. 1), and 21 species of Desmodesmus were identified including four new species (Table 1, Fig. 2). Desmodesmus armatus was the most widely distributed, being detected at 10 sites. In contrast, certain species were only found at a single site; for example, D. communis was only found at Hirao-yon-chome-ike; D. insignis was only detected at Kannonji-tsutsumi. D. insignis and D. communis were detected at Kannonji-tsutsumi and Hirao-yon-chome-ike, respectively, throughout the sampling period.

Survey and sampling sites in Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan. Sites (black dots) are numbered from north to south and represent areas from which Desmodesmus culture strains could be established (Table 1). White circles represent sites that were surveyed but where Desmodesmus was not detected. Sites 3, 5, 12, 17, 20 were the study sites referenced in Demura et al.26.

Molecular phylogenetic analyses of the maximum likelihood method and the Bayesian phylogenetic inference using ITS2 sequences derived almost identical phylogenetic trees (Fig. 3). In Clade 2, eight strains, including dSDes-Koumin3, dSgDes-Shizu1, and dSgDes-Ko2; dSgDes-ecoJ1, dSgDes-ecoOc3, and dSgDes-ecoApr(belonging to phylogenetic lineage D); and dSgDes-Nemu1and dSgDes-YO2-1 (belonging to phylogenetic lineage E), formed a clade that was sister to dSgDes-Hasu1, which showed 100% homology with the sequence represented by GenBank accession number MK447733, identified by D. opoliensis. Therefore, strain dSgDes-Hasu1 was identified as D. opoliensis based on the ITS2 sequence from GeneBank and on the morphology of naviculoid or fusiform inner cells (Fig. 4D), which is consistent with that of the species described previously27 however, the inner cells of the eight strains were not naviculoid or fusiform, but were bale-shaped (Fig. 4A). The density of cell surface microprojections (warts) was 20–30/µm2 for cells of the eight strains (Fig. 4C), and 1–2/µm2 for dSgDes-Hasu1 cells (Fig. 4E). The ridges on cells of the eight strains had small fold-like structures (height: 0.2 µm; Fig. 4A, B) that were not present on those of dSgDes-Hasu1 cells (Fig. 4D). These morphologies, i.e., cell morphology, number of dots, ridges, etc., were stable at different growth stages and under different culture conditions. CBCs were detected between dSgDes-Hasu1 and the eight strains for 2–3 locations, but not among the eight strains (Table 2, Fig. 5A). The sequence difference (%) between D. opoliensis (strain dSgDes-Hasu1) and the eight strains ranged from 2.11 to 3.38% (Table 2). The sequence difference (%) among strains with undetectable CBC ranged from 0.42 to 3.38% (Table 2).

Phylogenetic tree constructed using maximum likelihood method using internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) sequences. Bootstrap values greater than 70 are shown with posterior probability. Letters from A to P represent multiple culture strains that resulted in the same sequence (Table 1). Abbreviations for the public culture collections; CCAP, Culture Collection of Algae & Protozoa at the Scottish Association for Marine Science; SAG, The Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Göttingen; UTEX, Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Texas.

Scanning electron micrographs of the strain dSgDes-Oc3 (A,B,C), representing a type strain of Desmodesmus notatus; and the strain dSgDes-Hasu1 (D,E), identified as D. opolinensis. (A) Coenobium of the strain dSgDes-Oc3, with small folds on the ridges of each cell (indicated by arrows). (B) A part of the outer cell and small fold (indicated by arrows). (C) Magnified view of cell surface of the strain dSgDes-Oc3 showing a high density of microprojections (warts). (D) Coenobium of the strain dSgDes-Hasu1. (E) Magnified view of cell surface of the strain dSgDes-Hasu1 showing a low density of warts.

Secondary structures of the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) sequence. (A) secondary structure of the type strain dSgDes-ecoOc3 (Desmodesmus notatus) with high similarity to the ITS2 sequence of the D. opoliensis strain dSgDes-Hasu1. (B) secondary structure of the type strain dSgKDesA3 (D. lamellatus) with high similarity to the ITS2 sequence of the D. lefevrei strain dSgDes-eco12. (C) Secondary structure of the type strain dSgBigDes4/1 (D. fragilis) with high similarity to the ITS2 sequence of the D. intermedius strain dSgDes-Hyo. (D) Secondary structure of the type strain dSgKDes4/2 (D. reticulatus) with high similarity to the ITS2 sequence of the D. intermedius strain dSgDes-Hyo. I to IV indicated helix information. The black arrows in the secondary structure indicate the position of the compensating base changes (CBCs). The white arrows in the secondary structure indicate the position of the hemi-compensating base changes (hemi-CBCs).

Clade 3-1 mainly comprised species with asymmetric spines at both ends of their cells (Fig. 6A, arrows). However, the cells of strains dSgDes-0 and dSgKDesA3 that formed a clade with a high bootstrap value (99) and posterior probability (1.00) did not have asymmetric spines at either end, although there was a short spine at the ends of all cells (Fig. 6B, C, arrows). In addition, cells of strains dSgDes-0 and dSgKDesA3 had tube-like structures on their cell ridges (Fig. 6B, arrowheads). The cells of strain dSgKDesA3 had a large fold-like structure on each of their ridges as stable morphology, which was not observed for cells of other Desmodesmus species (Fig. 5B). The strains dSgDes-0 and dSgKDesA3 formed a clade with D. lefevrei and D. pirkollei (Fig. 3). No CBCs were detected between the strain dSgDes-0 and D. lefevrei or D. pirkollei (Table 3). However, one CBC each was detected between the strain dSgKDesA3 and strains of D. lefevrei or D. pirkollei (Table 3, Fig. 5B). The number of hemi-CBCs detected between strain dSgDes-0 and the other strains being compared was the lowest for dSgKDesA3 (Table 3). The sequence difference (%) between dSgDes-0 and dSgKDesA3 was 1.29%, a low value among closely related strains (Table 3).

Scanning electron micrographs of the strain dSgDes-eco12 (A), identified as Desmodesmus lefevrei; the strain dSgKDesA3 (B), representing a type strain of D. lamellatus; and the strain dSgDes-0 (C). (A) Coenobium of the strain dSgDes-eco12 with asymmetric spines (arrows). (B) Coenobium of the strain dSgKDesA3 with a large fold-like structure on the ridges of the cells (asterisks), tube-like structures on the cell ridges (arrowheads), and short spines (arrows). (C) Coenobium of the strain dSgDes-0 with tube-like structures on the cell ridges (arrowheads), and short spines (arrows).

Although strain dSgDes-eco12 was identified as D. pirkollei by Demura et al.26, it was classified as D. lefevrei in this study owing to the absence of branched warts characteristic of D. pirkollei16, and to the ITS2 sequence being monophyletic (sister position) with that of D. lefevrei with a high bootstrap value (94) and posterior probalility (0.85) (Fig. 3).

In the Clade 3-2, the lineage H (dSgDes-Nemu3, dSgBigDes4/1) and G (dSgHokuzan2, dSgDes-Hyo, dSgDes-Kami), which was identified as D. intermedius, formed a robust clade supported by a high bootstrap value (100) and posterior probalility (1.00) (Fig. 3). This clade was monophyletic with the lineage I (dSgKDes12/2, dSgKDes4/2) with a high bootstrap value (99) and posterior probalility (0.99) (Fig. 3). The cells of strains in the lineage H were similar to those of D. intermedius in the presence of spines at both ends, but differed from those of D. intermedius in the absence of a reticulate pattern on the cell surface (Fig. 7A–D). Compared to those of other Desmodesmus strains, cells in the lineage H were often crushed during pretreatment for SEM. The cells of strains in the lineage I had a reticular pattern (size 0.1–0.3 μm, Fig. 7E, F) of surface structure similar to those of D. intermedius; however, spines were absent (Fig. 7E), although fold-like structure were present at the outer edge of terminal cells (Fig. 7E, arrow). One or three CBCs were detected among the lineages G (D. intermedius), H, and I (Table 4, Fig. 5C, D). The sequence difference (%) among the three species ranged from 2.36 to 6.67%.

Scanning electron micrographs of the strain dSgDes-Hyo (A,B), identified as Desmodesmus intermedius; the strain dSgBigDes4/1 (C,D), representing a type strain of D. fragilis; and the strain dSgKDes4/2 (E,F), representing a type strain of D. reticulatus. (A) Coenobium of the strain dSgDes-Hyo. (B) A reticulate pattern on the cell surface of the strain dSgDes-Hyo. (C) Coenobium of the strain dSgBigDes4/1. (D) Cell surface of the strain dSgBigDes4/1. (E) Coenobium of the strain dSgKDes4/2 with small fold-like structures on the outer cells (arrows). (F) A reticulate pattern on the cell surface of the strain dSgKDes4/2.

Descriptions of new taxa

Desmodesmus notatus Demura, sp. nov.

Holotype: TNS-AL-63142 in TNS (Department of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science), Japan. This represents the dried algal material prepared from the strain dSgDes-ecoOc3 for SEM.

Ex-holotype strain: Strain dSgDes-ecoOc3, maintained in Demura Laboratory, Saga Algal Industry R&D Center, Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan. The strain was isolated from Hirano-yon-chome-ike, Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan (N33.299276, E130.293793).

DNA sequence: ITS2 (LC777154).

Description: coenobia size was 13.2 ± 1.2 μm × 19.9 ± 2.6 μm (Fig. 2A). Coenobium of four cells was observed with the outer cells bearing spines. The inner cells were bale-shaped. The size of spines was 11.9 ± 1.2 μm. Microprojections (warts) were present on the cell surface, at a density of 20–30/µm2. Folds of height approximately 0.2 μm were present on the ridges of the cells. This species was monophyletic (sister taxon) with D. opoliensis in the phylogenetic tree constructed using ITS2 sequences; however, it can be distinguished from D. opoliensis by its bale-shaped inner cells, density of warts, ridges on the cells, and by the presence of CBC between both species.

Etymology: the specific epithet “notatus” is derived from the Latin word meaning “pattern of small dots”.

Morphological keys that identify D. notatus and D. opolienesis.

-

1.

Inner cell morphology: Bale-shaped..…D. notatus, Naviculoid or fusiform..…D. opolienesis.

-

2.

Density of wall surface warts: High..…D. notatus, Low..…D. opolienesis.

-

3.

Edges on the cells: Present..…D. notatus, Absent..…D. opolienesis.

Desmodesmus lamellatus Demura, sp. nov.

Holotype: TNS-AL-63143 in TNS (Department of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science), Japan. This represents the dried algal material prepared from the strain dSgKDesA3 for SEM.

Ex-holotype strain: Strain dSgKDesA3 maintained in Demura Laboratory, Saga Algal Industry R&D Center, Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan. The strain was isolated from Kannonji-tsutsumi, Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan (N33.327028, E130.298031).

DNA sequence: ITS2 (LC777107).

Description: coenobia size was 6.8 ± 1.2 μm × 10.8 ± 2.4 μm (Fig. 2B). Coenobium of four cells was observed, which did not contain any long spines. The ridge of each cell was surrounded by a fold of approximately 1 μm length. This species exhibited a large fold-like structure on each of their ridges as a stable morphology, a feature not observed in cells of other Desmodesmus species. Tube-like structures were present within these folds. Short spines of 1–1.5 μm length were present at the ends of all cells. One CBC each was detected between this species and D. lefevrei and D. pirkollei.

Etymology: the specific epithet “lamellatus” is derived from the Latin word meaning “folded”.

Morphological key that identifies D. lamellatus from D. leferei and D. pirkollei.

-

Large fold-like structure: Present..…D. lamellatus, Absent..…D. leferei and D. pirkollei.

Desmodesmus fragilis Demura, sp. nov.

Holotype: TNS-AL-63144 in TNS (Department of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science), Japan. This represents the dried algal material prepared from the strain dSgBigDes4/1 for SEM.

Ex-holotype strain: Strain dSgBigDes4/1 maintained in Demura Laboratory, Saga Algal Industry R&D Center, Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan. The strain was isolated from Kose Park Creek, Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan (N33.255848, E130.325748).

DNA sequence: ITS2 (LC777172).

Description: coenobia size was 5.2 ± 0.8 μm × 13.0 ± 3.4 μm (Fig. 2C). Coenobium of four cells was observed, the outer cells of which contained spines. The size of the spines was 6.7 ± 0.7 μm. Except for small dots on the cell surface, no other structures were observed. This species was monophyletic (sister taxon) with D. intermedius in the phylogenetic tree constructed using ITS2 sequences. However, this species is clearly distinguished from D. intermedius, which has a reticulate structure on the cell surface. Two CBCs were detected between this species and D. intermedius.

Etymology: the specific epithet “fragilis” is derived from the Latin word meaning “fragile”.

Desmodesmus reticulatus Demura, sp. nov.

Holotype: TNS-AL-63145 in TNS (Department of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science), Japan. This represents the dried algal material prepared from the strain dSgKDes4/2 for SEM.

Ex-holotype strain: strain dSgKDes4/2 maintained in Demura Laboratory, Saga Algal Industry R&D Center, Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan. The strain was isolated from Kannonji-tsutsumi, Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan (N33.327028, E130.298031).

DNA sequence: ITS2 (LC777110).

Description: coenobia size was 3.5 ± 0.5 μm × 6.1 ± 0.9 μm (Fig. 2D). Coenobium of four cells was observed, which did not contain any spines. A reticulum of size 0.1–0.3 μm was present on the cell surface. Small fold-like structures of height 0.3–0.5 μm were present on the outer cells. This species was monophyletic (sister taxon) with D. intermedius and D. fragilis in the phylogenetic tree constructed using ITS2 sequences. However, this species is clearly distinguished from D. intermedius and D. fragilis, which have spines at the ends of the cell. Three CBCs were detected between this species and D. intermedius or D. fragilis.

Etymology: the specific epithet “reticulatus” is derived from the Latin word meaning “reticulated”.

Morphological keys that identify D. intermedius, D. fragilis and D. reticulatus.

-

1.

A reticulum structure on the cell surface: Present..…D. intermedius, D. reticulatus, Absent..…D. fragilis.

-

1a.

Spines at the ends of the cell: Present…..D. intermedius, Absent…..D. reticulatus.

-

2.

Small fold-like structures on the outer cells: Present..…D. reticulatus, Absent..…D. intermedius and D. fragilis.

Discussion

This study revealed the distribution of Desmodesmus species within the limits of Saga City (431.4 km2). In the present study, Desmodesmus was present at more than half (55.3%) of the surveyed sites. The actual percentage is expected to be much higher because this survey was limited to 1 L of surface water, and many of the sites were surveyed only once. In addition, based on the habitat diversity of freshwater environments that includes ponds, wetlands, dams, artificial ponds, and creeks, and considering that D. insignis and D. communis can be found throughout the entire sampling period, Desmodesmus is considered a genus capable of adapting to a wide range of environmental conditions.

In the present study, D. armatus was identified at many sites, with no regular occurrence pattern being observed regarding sites, environments, or seasons. Vanormelingen et al.28 reported genetic and morphological variations in D. armatus strains found in adjacent ponds in response to predation pressures and environmental differences. The fact that D. armatus was found in a highly variable environment in this study indicates its adaptive nature.

Of the species recorded in the present study, D. communis has the most documented occurrence worldwide; Hegewald & Braband7 identified strains of this species from Europe, India, North America, South America, and New Zealand. However, in the present study, D. communis was only found in one pond (Hirao-yon-chome-ike), where it was observed throughout the entire sampling period. Different species may exhibit varying distribution and diffusion patterns, and further studies are required to confirm this aspect.

In the present study, D. notatus was found to be genetically closely related to D. opolinensis; however, differences in cell morphology and surface structure, as well as in the presence of CBC between the two species, classified these as different species. The maximum sequence difference (3.38%) among D. notatus strains was identical to the sequence difference (3.38%) between the strain of D. opolinensis and strain dSgDes-Ko2 of D. notatus. Zou et al.29 reported the presence of 1.1 to 21.7% interspecific sequence differences in ITS (probably a combined ITS1 and ITS2 sequence) among species of Scenedesmus, which is very closely related to Desmodesmus, indicating the difficulty of identifying species by sequence difference alone in the case of Desmodesmus.

Desmodesmus notatus was found in six ponds and creeks in Saga City, and showed high genetic diversity compared to other species; therefore, it is likely that, similar to D. armatus, it will be found in a wider area in the future.

The strains dSgDes-0 and dSgDes-eco12 were previously identified as D. pirkollei by Demura et al.26. However, in the present study, detailed morphological observations revealed that the strain dSgDes-eco12 was D. lefevrei. The strain dSgDes-0 could also be identified as D. lamellatus for the following two reasons: first, it formed a robust clade with the strain dSgKDesA3 (D. lamellatus), and second, no CBCs were identified between the strains dSgDes-0 and dSgKDesA3, and the number of hemi-CBCs was the lowest. However, large folds on the cell ridges, a morphological feature of D. lamellatus, were rarely observed for the dSgDes-0 strain, and additionally, no CBCs were identified between the dSgDes-0, D. lefevrei, and D. pirkollei strains. Undoubtedly, ITS2 is very effective in classifying Desmodemus; however, the limitations of analysis using ITS2 alone may be experienced. More detailed molecular phylogenetic analyses, with the addition of sequence data of ITS full length sequence (ITS1, the 5.8S rRNA gene, ITS2), chloroplast and mitochondrial genes are warranted for accurate identification of the dSgDes-0 strain in the future.

Desmodesmus fragilis cells exhibited an extremely limited surface structure, despite the presence of reticulate structures on the cell surfaces of the closely related D. intermedius and D. reticulatus. The role of “cell wall structures” of Desmodesmus is unknown, although some studies have been conducted on the “spines” that may influence buoyancy30. Desmodesmus fragilis cells are very fragile and are easily crushed compared with those of other Desmodesmus species, indicating that cell wall structures may play a role in protecting the cell structure.

The water bodies investigated in this study comprise a variety of environments that include ponds, wetlands, dams, artificial ponds, and creeks. Demura et al.3 reported water quality surveys over a period of more than one year for the ponds Kannonji-tsutsumi and Hirao-yon-chome-ike, and found that the total nitrogen, total phosphorus, and organic matter concentrations for Hirao-yon-chome-ike exceeded those for Kannonji-tsutsumi, indicating that Hirao-yon-chome-ike is a highly eutrophic pond. In the present study, D. serratus, D. arthrodesmiformis, D. lamellatus, and D. reticulatus were detected from Kannonji-tsutsumi but not from Hirao-yon-chome-ike, whereas D. communis, D. tropicus, D. notatus, D. subspcatus, D. protuberans, and D. lefervrei were detected from Hirao-yon-chome-ike but not from Kannonji–tsutsumi, which suggests that the differences in species composition likely reflect differences in water quality.

Although the survey area in the present study was geographically limited, it is expected that extending this study will lead to a better understanding of the distribution of Desmodesmus throughout Japan and worldwide. To understand the true diversity of Desmodesmus and the evolutionary process of its distribution, it is necessary to investigate not only the water quality, but also the interrelationships with coexisting organisms, birds, wind, etc., all of which serve as vectors for its distribution.

Research on the utilization of microalgal biomass, not only for fuels but also for pharmaceuticals and food products, is developing extensively31,32. Microalgal biomass has also attracted attention from Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and carbon-neutrality perspectives33. Desmodesmus is a candidate microalga for algal biomass production owing to its high productivity and tolerance to various water qualities8,9. Although studies have reported the mass cultivation of Desmodesmus34, actual commercialization of the genus has yet to begin. To use Desmodesmus for biomass production in the future, it is necessary to search for culture strains with properties such as rapid growth and ability to produce commercially useful substances. The present study revealed > 20 Desmodesmus species, exhibiting high genetic diversity, in a small area. The results of this study indicate that Desmodesmus possesses a variety of characteristics, and that useful culture strains can be established even in local area.

Materials and methods

Distribution survey and strain establishment

Distribution surveys were conducted across 38 water bodies in Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan, from June 2017 to March 2023 (Fig. 1, Table 1). Surface water samples (1 L) were collected in plastic bottles. These were brought back to the laboratory and placed at 10 °C for approximately 15 h. Thereafter, the sedimentary microalgae that settled at the bottom were observed under an inverted light microscope (CKX53; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to determine the presence or absence of Desmodesmus. When Desmodesmus was detected, the culture strain was established by the method described by Demura et al.26. In brief, the coenobium of Desmodesmus was isolated from the water sample using a micropipette35 under an inverted light microscope (CKX53; Olympus). All established strains were maintained in 15 mL test tubes containing AF6 medium36 at 25 °C under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle using white fluorescent illumination (approximately 100 µmol photons m−2 s−1). In total, 86 new strains were established in unialgal culture and in a clonal state (Table 1).

Observation by using scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

For SEM, 10 mL of the culture was centrifuged at 2000×g for 5 min (KUBOTA 3740, KUBOTA CO., Tokyo, Japan) at 25 °C. After removing the supernatant, the sedimented coenobia were resuspended in 500 µL of deionized water. Then, 5 µL of the resuspended mixture was pipetted onto a cellulose ester membrane filter (ADVANTEC, Tokyo, Japan) or RO membrane (ADVANTEC), following which 5 µL of 2% ionic liquid HILEM IL1000 (Hitachi High-Tech Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was added to it by pipetting. Thereafter, the samples were air dried for approximately 15 h at 25 °C, sputtered with platinum (JFC-1600; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), and subjected to SEM using a JSM-6510 microscope (JEOL) with the following settings: voltage of 15 kV and working distance of “10”.

Phylogenetic analysis and species identification

DNA was isolated from each sample and the ITS region, containing a part of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene, the ITS1, the 5.8S rRNA gene, the ITS2 and a part of the 28S rRNA gene, was amplified following the methods described by Demura et al.26. Since the study by An et al.10, molecular phylogenetic and secondary structure analyses of Desmodesmus have been performed using only ITS2; therefore, the data that exist in GenBank are often ITS2-only. In addition, because taxonomic studies of Desmodesmus have been sufficiently successful with ITS2 sequences [e.g., Refs.7,10,15,16], ITS2-only sequences were used in the present study. A total of 127 sequences, including 86 new sequences and 46 database sequences from GenBank37, were used for phylogenetic analysis of the ITS2 region (approximately 236 bp). Identical sequences are collectively presented as “lineages A to P” on the molecular phylogenetic tree.

Sequence alignment was performed using the analysis software MAFFT38 with default settings, except for changing “L-INS-i” in “iterative refinement methods” in the “advanced settings” option. Aligned sequences were checked manually using AliView39, and sites with gaps in more than half of the sequences were removed. Molecular phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum likelihood method and IQ-Tree40. The settings selected in “substitution model options” in IQ-Tree were “Substitution model Auto” and “FreeRate heterogeneity Yes [+ R].” In addition, the bootstrap analysis standard and the number (100) of bootstrap alignments were chosen. The molecular phylogenetic tree was edited using FigureTree41.

Bayesian phylogenetic inference was performed using PhyloBayes version 4.142 with the same dataset used for the maximum likelihood phylogeny estimation. Two independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were run under the general time-reversible (GTR) substitution model with discrete gamma-distributed among-site rate heterogeneity. Chain convergence and stationarity were assessed using the bpcomp program in PhyloBayes. The first 10,000 generations were discarded as burn-in, and trees were sampled every 10th generation from the subsequent 15,000 generations. The two chains were confirmed to have converged sufficiently (maxdiff < 0.1).

Identification of the species was performed by confirming that the ITS2 sequence of the strain established in this study was monophyletic with the database sequences of the described species, and that the morphological characteristics were consistent with those of the species reported in previous studies5,6,7,10,15,16,23,26,27,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56.

Comparison of RNA secondary structure

Some strains could not be identified by molecular phylogenetic analysis of ITS2 sequence or morphological observation using SEM; for these, the RNA secondary structures were compared using the CBC and hemi-CBC of related strains. A one-to-one structural comparison was performed using the software LocARNA57 with default settings, and the CBC and hemi-CBC were visually counted. The ITS2 sequence diversity comparison (sequence difference, %) was calculated manually by comparing alignment sequences performed using LocARNA.

Data availability

The dataset used in this study in available upon reasonable request through the following email contact: st8148@cc.saga-u.ac.jp.

Change history

15 November 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79441-9

References

Çelekli, A., Öztürk, B. & Kapı, M. Relationship beween phytoplankton composition and environmental variables in an artificial pond. Algal Res. 5, 37–41 (2014).

Halder, P., Debnath, M. & Ray, S. Occurrence and diversity of microalgae in phytoplankton collected from freshwater community ponds of Hooghly District, West Bengal, India. Plant Sci. Today 6, 8–16 (2019).

Demura, M., Honjo, A., Ohi, Y., Noma, S. & Hayashi, N. Annual survey of microalgal diversity and water quality factors in 3 freshwater areas of Saga City, Saga Prefecture, Japan—The search for microalgae candidates of mass culture. Jpn. J. Phycol. 71, 1–12 (2023).

Baudelet, P.-H., Ricochon, G., Linder, M. & Muniglia, L. A new insight into cell walls of Chlorophyta. Algal Res. 25, 333–371 (2017).

Hegewald, E. & Braband, A. A taxonomic revision of Desmodesmus serie Desmodesmus (Sphaeropleales, Scenedesmaceae). Fottea 17, 191–208 (2017).

Vanormelingen, P. et al. The systematics of a small spineless Desmodesmus species, D. costato-granulatus (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyceae), based on ITS2 rDNA sequence analyses and cell wall morphology. J. Phycol. 43, 378–396 (2007).

Hegewald, E., Schmidt, A., Braband, A. & Tsarenko, P. Revision of the Desmodesmus (Sphaeropleales, Scenedesmaceae) species with lateral spines. 2. The multi-spined to spinless taxa. Algol. Stud. 116, 1–38 (2005).

Ye, S. et al. Simultaneous wastewater treatment and lipid production by Scenedesmus sp. HXY2. Bioresour. Technol. 302, 122903 (2020).

Premaratne, M., Liyanaarachchi, V. C., Nishshanka, G. K. S. H., Nimarshana, P. H. V. & Ariyadasa, T. U. Nitrogen-limited cultivation of locally isolated Desmodesmus sp. for sequestration of CO2 from simulated cement flue gas and generation of feedstock for biofuel production. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105765 (2021).

An, S. S., Friedl, T. & Hegewald, E. Phylogenetic relationships of Scenedesmus and Scenedesmus-like coccoid green algae as inferred from ITS-2 rDNA sequence comparisons. Plant Biol. 1, 418–428 (1999).

Meyen, F. J. F. Beobachtungen über einige niedere Algenformen. Verhandl. Kais. Leop. Carol. Akad. Naturf. 14, 769–778 (1828).

Trainor, F. R. Cyclomorphosis in Scenedesmus communis Hegew. Ecomorph expression at low temperature. Br. Phycol. J. 27, 75–81 (1992).

Morales, E. A. & Trainor, F. R. Algal phenotypic plasticity: Its importance in developing new concepts the case for Scenedesmus. Algae 12, 147–157 (1997).

Lürling, M. Phenotypic plasticity in the green algae Desmodesmus and Scenedesmus with special reference to the induction of defensive morphology. Ann. Limnol. Int. J. Lim. 39, 85–101 (2003).

Hegewald, E., Schmidt, A. & Schnepf, E. Revision of the Desmodesmus species with lateral spines. 1. Desmodesmus subspicatus (R. Chod.) E. Hegew. et A. Schmidt.. Algol. Stud. Arch. Hydrobiol. Suppl. 101, 1–26 (2001).

Hegewald, E., Coesel, P. F. M. & Hegewald, P. A phytoplankton collection from Bali, with the description of a new Desmodesmus species (Chlorophyta, Scenedesmaceae). Algol. Stud. 105, 51–78 (2002).

Coleman, A. W. The significance of a coincidence between evolutionary landmarks found in mating affinity and a DNA sequence. Protist 151, 1–9 (2000).

Hoshina, R., Hayakawa, M. M., Kobayashi, M., Higuchi, R. & Suzaki, T. Pediludiella daitoensis gen. et sp. nov. (Scenedesmaceae, Chlorophyceae), a large coccoid green alga isolated from a Loxodes ciliate. Sci. Rep. 10, 628 (2020).

Behnke, A., Friedl, T., Chepurnov, V. A. & Mann, D. G. Reproductive compatibility and rDNA sequence analyses in the Sellaphora pupula species complex (Bacillariophyta). J. Phycol. 40, 193–208 (2004).

Nguyen, M. L. et al. DNA signaturing derived from the internal transcribed spacer 2(ITS2): A novel tool for identifying Desmodesmus species (Scenedesmoaceae, Chlorophyta). Fottea 23, 1–7 (2023).

Bica, A. et al. Desmodesmus communis (Chlorophyta) from Romanian freshwaters: coenobial morphology and molecular taxonomy based on the ITS2 of new isolates. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 17, 16–28 (2012).

Gopalakrishnan, K. K., Novis, P. M. & Visnovsky, G. Alpine Scenedesmaceae from New Zealand: New taxonomy. N. Z. J. Bot. 52, 84–99 (2014).

Shubert, E., Wilk Woźniak, E. & Ligęza, S. An autecological investigation of Desmodesmus: Implications for ecology and taxonomy. Plant Ecol. Evol. 147, 202–212 (2014).

Miyauchi, T. Plankton in the Kasumigaura. Jpn. J. Limnol. 5, 26–32 (1935).

Hada, Y. Plankton of lake Harutori at Kusiro, Hokkaido. Jpn. J. Limnol. 8, 396–409 (1938).

Demura, M., Noma, S. & Hayashi, N. Species and fatty acid diversity of Desmodesmus (Chlorophyta) in a local Japanese area and identification of new docosahexaenoic acid-producing species. Biomass 1, 105–118 (2021).

Richter, P. G. Scenedesmus opoliensis P.Richt, nov. sp.. Z. Angew. Mikrosk. 1, 3–7 (1895).

Vanormelingen, P., Vyverman, W., De Bock, D. & Van der Gucht, K. Local genetic adaptation to grazing pressure of the green alga Desmodesmus armatus in a strongly connected pond system. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 503–511 (2009).

Zou, S. et al. How DNA barcoding can be more effective in microalgae identification: A case of cryptic diversity revelation in Scenedesmus (Chlorophyceae). Sci. Rep. 6, 36822 (2016).

Conway, K. & Trainor, F. R. Scenedesmus morphology and flotation. J. Phycol. 8, 138–143 (1972).

Chandrasekhar, K. et al. Algae biorefinery: A promising approach to promote microalgae industry and waste utilization. J. Biotechnol. 345, 1–16 (2022).

Ubando, A. T., Ng, E. A. S., Chen, W. H., Culaba, A. B. & Kwon, E. E. Life cycle assessment of microalgal biorefinery: A state-of-the-art review. Bioresour. Technol. 360, 127615 (2022).

Onyeaka, H. et al. Minimizing carbon footprint via microalgae as a biological capture. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 1, 100007 (2021).

Nagappan, S. & Verma, S. K. Growth model for raceway pond cultivation of Desmodesmus sp. MCC34 isolated from a local water body. Eng. Life Sci. 16, 45–52 (2016).

Andersen, R. A. & Kawachi, M. Traditional microalgae isolation techniques. In Algal Culturing Techniques (ed. Andersen, R. A.) 83–100 (Elsevier, 2005).

Kasai, F., Kawachi, M., Erata, M. & Watanabe, M. M. NIES-Collection List of Strains 7th edn, 7–9 (National Institute for Environmental Studies, USA, 2004).

Benson, D. A. et al. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 17–20 (2002).

Katoh, K., Rozewicki, J. & Yamada, D. K. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 20, 1160–1166 (2019).

Larsson, A. AliView: A fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 30, 3276–3278 (2014).

Trifinopoulos, J., Nguyen, L. T., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. W-IQ-TREE: A fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W232–W235 (2016).

Rambaut A. FigTree v1.4.4. (2024). http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/.

Lartillot, N. & Philippe, H. A bayesian mixture model for across-site heterogeneities in the amino-acid replacement process. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1095–1109 (2004).

Chodat, R. Scenedesmus. etude de génétique, de systématique expérimentale et d’hydrobiologie. Schweiz. Z. Hydrol. 3, 71–258 (1926).

Demura, M. Nomenclatural validation of Desmodesmus dohacommunis (Chlorophyta). Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci. Ser. B Bot. 48, 51–52 (2022).

Dragos, N. et al. Desmodesmus tropicus (Chlorophyta) in the Danube Delta—Reassessing the phylogeny of the series Maximi. Euro. J. Phycol. 54, 300–314 (2019).

Fawley, M. W., Fawley, K. P. & Hegewald, E. Desmodesmus baconii (Chlorophyta), a new species with double rows of arcuate spines. Phycologia 52, 565–572 (2013).

Jeon, S. L. & Hegewald, E. A revision of the species Desmodesmus perforatus and D. tropicus (Scenedesmaceae, Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta). Phycologia 45, 567–584 (2006).

Korshikov AA. Bakuol'ni (Vacuolales) ta Protokokovi (Protococcales) in Viznachnik prisnovodnihk vodorostey Ukrainsykoi RSR. 1–439 (Akademyy Nauk Ukrayins'koy RSR, Kyiv, Ukrainsykoi RSR. (1953).

Lemmermann, E. Das phytoplankton sächsischer teiche. Forsch. Aus Der Biol. Stn. Plön 7, 96–135 (1899).

Satpati, G. G. & Pal, R. SEM study of planktonic chloropytes from the aquatic habitat of the Indian Sundarbans and their conservation status. J. Threat. Taxa 11, 14722–14744 (2019).

Staehelin, L. A. & Pickett-Heaps, J. D. The ultrastructure of Scenedesmus (Chlorophyceae). I. Species with the “reticulate” or “warty” type of ornamental layer. J. Phycol. 11, 163–185 (1975).

Tell, G. & Vinocur, A. L. Taxonomy, morphological variability, and ecology in Scenedesmus opoliensis Richt. (Chlorococcales). Crypt. Bot. 2, 93–103 (1991).

Tsarenko, P. M., Hegewald, E. & Krienitz, L. LM and SEM studies on Scenedesmus of lake Tollense (Baltic Lake District, Germany). Algol. Stud. 82, 13–36 (1996).

Tsarenko, P. M., Hegewald, E. & Braband, A. Scenedesmus-like algae of Ukraine. 1. Diversity of taxa from water bodies in Volyn Polissia. Algol. Stud. 118, 1–45 (2005).

West, W. & West, G. S. A contribution to our knowledge of the freshwater algae of Madagascar. Trans. Linn. Soc. Bot. Lond. 5, 41–90 (1895).

Wu, L., Xu, L. & Hu, C. Screening and characterization of oleaginous microalgal species from Northern Xinjiang. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25, 910–917 (2015).

Raden, M. et al. Freiburg RNA tools: A central online resource for RNA-focused research and teaching. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W25–W29 (2018).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Biomass Industry Promotion Division of Saga City for their support of this study. In addition, I would like to thank Dr. N. Ryuda for her advice on SEM sample preparation, and Dr. T. Nakayama for his advice on molecular phylogenetic analysis. I would also like to thank Dr. A. Tuji for confirmation of the rule “International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen code).” I would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing. SEM was conducted using equipment shared for the MEXT project to promote the public utilization of advanced research infrastructure (Program for supporting the introduction of the new sharing system; Grant Numbers JPMXS0422400020 and JPMXS0422400021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was conducted by M. Demura.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in Figures 4 and 6, where the scales were displayed incorrectly.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Demura, M. New species and species diversity of Desmodesmus (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) in Saga City, Japan. Sci Rep 14, 18980 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69941-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69941-z