Abstract

The subgrade crushed-rocks of Gonghe-Yushu (Gongyu) Expressway in Qinghai Province are seriously weathered, resulting in a series of pavement diseases. Among the weathered crushed-rocks, the weathering degree of slate is particularly serious, and its physical and mechanical properties, weathering resistance and applicability are not clear. Therefore, this paper takes the slate in the subgrade crushed-rocks of Gongyu Expressway as the research object, and drills the core of the slate rock block to make a cylindrical standard sample, and uniaxial and triaxial compression tests, nuclear magnetic resonance tests, and electron probe micro-analysis tests were performed on it within 50 freeze–thaw cycles (FTC) under saturated conditions. According to the test results, the mass, longitudinal wave velocity, and strength of the slate specimens all decrease with the increase of the number of FTC, the cohesion \(({\text{C}})\) increases first and then decreases, and the change trend of internal friction angle (φ) is completely opposite to the cohesion. The FTC has an expansion effect on the pores of the slate specimens, and the microstructure of the rock particles on the specimen’s surface is removed and becomes smooth. The results of mechanical tests are used in the Hoek–Brown (H-B) strength criterion, and a unified expression of the H-B criterion suitable for slate in permafrost regions is established. The above conclusions can provide some construction reference and maintenance of high-grade highways in cold regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

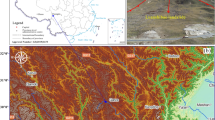

In China, permafrost is widely distributed, of which permafrost accounts for about 22.4% of the country’s land area, mainly distributed in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the northwest mountains and the northeast Xing’an Mountains and other regions1. Qinghai Province is situated on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the climate is dry and cold, the terrain is complex and steep. Therefore, Qinghai has a large area of permafrost distribution. Gongyu Expressway is China’s first high-grade highway in permafrost regions. The highway has an average altitude of more than 4100 m and a total length of 634.8 km, of which 227 km are located in permafrost region, accounting for about 36% of the total length of the line. A series of problems such as thaw collapse and longitudinal and transverse cracks were found on the pavement of Gongyu Expressway during the disease investigation. The pavement disease and subgrade crushed-rocks are shown in Fig. 1.

The crushed-rocks subgrade uses crushed-rocks as subgrade fillers, as shown in Fig. 2a. In order to protect the thermal stability of permafrost under the subgrade and prevent the occurrence of road diseases, the crushed-rocks subgrade is adopted along the Gongyu Expressway2. The climate of the Tibetan Plateau is special, characterized by high altitude, high number of FTC, large diurnal temperature difference, and strong ultraviolet rays. These factors are easy to lead to the weathering of highway subgrade crushed-rocks, and the strength of the weathered stones is reduced. Under the action of wind load and traffic load, the surface of the rock is easy to crack and produce a large amount of debris. These debris fill the gaps, weakening the convective heat transfer function of the subgrade crushed-rocks, which seriously reduces the role of the crushed-rocks subgrade in protecting the permafrost. As a rock with high identification degree, slate can be seen everywhere in the investigation site, and its weathering degree is different. After weathering, slate cracks along the slate joint, mainly in the form of flake, strip and clastic, as shown in Fig. 2b.

So far, a great deal of research has been done by scholars at home and abroad on the physical and mechanical properties and mechanism of freeze–thaw (FT) rock. Ghobadi et al.3 studied the variation of shear parameters and degradation characteristics of jointed rocks under FTC; Tan et al.4 conducted uniaxial compression tests on granite samples under different FTC and found that the uniaxial compressive strength and elastic modulus decreased with the increase of FTC. Park et al.5 took basalt and tuff as the research object, and carried out the FT cycle test. During the test, they found that in the process of low-temperature frozen water transforming into ice, the volume of the rock would be slightly larger, the porosity would increase, cracks would appear on the surface of the rock, and particles would fall off at the corners. It was concluded that the frost heaving force generated inside the rock was the main cause of its weathering. To understand the FT damage mechanism of rock specimens, Khanlari et al.6 studied the wave velocity and uniaxial compressive strength of rocks during FTC. Zhang et al.7 observed that the mass of red sandstone specimens initially increased and then decreased after the FT cycle test. This is because during the early stage of the FT cycle, the original pores or cracks in the specimen developed due to frost heaving force, allowing water to enter and increase the saturated mass. In the later stage of FT cycle, due to the influence of frost heaving force, the specimen will fall off the rock particles first, resulting in a decrease in its saturated mass. Bayram8 investigated the relationship between the rock’s mechanical properties and its basic parameters through the uniaxial compression tests on volcanic clastic rock under different FTC, they established an empirical formula to estimate the loss of uniaxial compressive strength in the rock and concluded that the FT cycle is the main cause of changes in the rock’s physical and mechanical properties. Fu et al.9 conducted uniaxial compression tests with 7 different bedding angles and 6 different test temperatures to investigate the impact of low-temperature freezing on the failure type and compressive strength of slate, they analyzed the variations in the stress–strain curve, uniaxial compressive strength and failure type. Du et al.10 characterized the pore diameter distribution and microstructure of concrete under different FTC using SEM. Zhou et al.11 conducted NMR experiments to investigate the pore diameter distribution of sandstone under FTC. Liu et al.12 conducted uniaxial and triaxial compression tests on slates with different plane inclination angles, they combined the test results with the H-B strength criterion and determined the relevant parameters of the H-B empirical failure criterion and the H-B strength criterion for slates with different plane inclination angles through regression analysis, and the unified expression of H-B strength criterion of slate in the West Route Project Area of South-to-North Water Diversion was established. To study the influence of rock mass anisotropy, Shi et al.13 introduced anisotropy index to improve H-B strength criterion.

Understanding the degradation of physical and mechanical properties of subgrade materials under FTC is crucial for infrastructure stability in permafrost regions. Previous studies have extensively examined the impacts of FTC on various rock types, including granite, sandstone, and limestone. For instance, Eslami et al.14 obtained that the mechanical strength of limestone significantly decreases after multiple FTC, while Zhang et al.15 highlighted similar trends in sandstone. These studies primarily focus on general rock types and often overlook the specific conditions of highway subgrade materials in permafrost regions. In addition, this study innovatively applies the H-B strength criterion to slate under different FTC. Previous research has primarily focused on the application of the H-B criterion under conventional conditions16,17. The pioneering work by Hoek and Brown proposed this criterion and it has been widely used in strength prediction for various rock types18. However, few studies have applied the H-B strength criterion to slate in permafrost regions and explored the effects of different FTC on strength characteristics. Our research can provide reference for the design and maintenance of expressway projects in permafrost regions.

Currently, domestic and foreign scholars have less research on highway subgrade slate in permafrost regions. As a kind of crushed-rocks subgrade filler, the physical and mechanical properties, weathering resistance and applicability of slate are not clear. Therefore, it is of great significance to study the macro and micro FT damage degradation law of slate under FTC through laboratory tests to solve the stability of highway subgrade in permafrost regions. This study is mainly aimed at the FT damage of the subgrade slate of the Gongyu Expressway in Qinghai Province. Fresh slate specimens are taken to make international standard specimens for indoor tests. The indoor tests include saturated FT cycle tests, mass and wave velocity measurement tests, NMR tests, uniaxial and triaxial compression tests and EPMA tests. The mechanical test results are used for H-B strength criterion, and a unified expression of H-B criterion suitable for slate in permafrost regions is established.

Test process

Test materials

Slate specimens for physical and mechanical tests and NMR tests

The slate rocks are all from a quarry in Guoluo Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Qinghai Province, and the subgrade crushed-rocks of Gongyu Expressway are all from this quarry. According to the specifications19,20, core drilling specimens of rock blocks were taken as required, cut and polished into standard slate specimens of cylinders with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm. The mass and longitudinal wave velocity were measured, and specimens with similar mass and longitudinal wave velocity were screened. These screened specimens were divided into 5 groups, each containing 5 specimens (1 standby), totaling 25 specimens. The specimen numbers range from BY-1 to BY-25, as shown in Fig. 3.

Slate specimen for EPMA tests

In order to facilitate the observation of the changes in microstructure of slate under FTC, the complete slate specimen was cut into a flake specimen with a height of 25 mm, a width of 20 mm and a thickness of about 3 mm for the EPMA test. The cut slate specimen needs to be polished smooth on a grinding and polishing machine and fixed on the sample stage before conducting the EPMA test. The flake slate specimen and the sample stage are shown in Fig. 4.

FT cycle temperature selection

The daily average temperature of Maduo County was used as the data point, and the daily average temperature scatter plot of 1 year was drawn. The extreme daily average temperature point with large deviation was removed, and the scatter plot was fitted to the curve. The one-year temperature curve of Maduo County in 2021 is shown in Fig. 5.

The FT cycle test uses the one-year temperature curve of Maduo County as the temperature control curve of a single FT cycle, as shown in Fig. 6. In this experiment, each FT cycle lasted for 24 h. According to the relevant characteristic values of the curve and the shape of the curve, the minimum freezing temperature was − 13.85 °C, and the freezing time was about 14 h under negative temperature conditions. The highest melting temperature is 9.29 °C, and melting for 10 h under normal temperature conditions is a FT cycle.

Test schemes and equipment

The equipment required for indoor test is shown in Fig. 7, the FT cycle test schemes of each test are summarized as Table 1, and the test schemes and processes are as follows.

Physical tests

All the numbered 5 groups of slate specimens were put into an electric hot blast drying oven at 110 °C for 24 h, and then the mass and longitudinal wave velocity of the dried specimens were measured by electronic balance and NM-4A non-metallic ultrasonic detection analyzer. Before the FT cycle test, all the specimens were placed in a saturation device and saturated for 6 h under 0.1 MPa vacuum pressure, and then the specimens were placed in a glass dish for 4 h under atmospheric pressure, and measured the mass and longitudinal wave velocity of the saturated specimens. Then, the FT cycle test was carried out by using TMS9018-500 cold region engineering gradient FT cycle test chamber. Subsequently, the mass and longitudinal wave velocity of the slate specimens undergoing different FTC were measured. And the changes in mass and longitudinal wave velocity of slate specimens under different FTC were obtained.

NMR tests

The slate specimens with different FTC were first saturated with vacuum and then placed into MesoMR12-060H-I medium-size NMR imaging analysis system to obtain the T2 spectrum and porosity of slate specimens under different FTC.

Mechanical tests

Uniaxial and triaxial compression tests of slate specimens subjected to different numbers of FTC were carried out using FRTX-1000 low-temperature high-pressure servo-controlled rock triaxial testing system at normal temperature with the confining pressures taken as 100, 200 and 300 kPa in the triaxial tests, respectively. Axial strain control was adopted during the loading process, with a loading rate of 0.05 mm/min.

EPMA tests

The EPMA test was carried out by using JEOL JXA-8230 electron probe analyzer after the FT cycle test of the flaky slate specimen in the saturated state. In the backscatter mode, the COMPO image of the same position the slate specimen experience different FTC was amplified 2000 times for observing the effect of the FT cycle on the microstructure of the slate specimen.

Experimental study on physical and mechanical properties of slate under freeze–thaw cycles

Physical tests

Basic physical parameters

After the physical properties tests of slate, the average basic physical parameters of slate specimens are obtained by calculation and wave velocity measurement, as shown in Table 2.

Mass change

To determine the mass changes of slate specimens during the FT cycle, the mass data were processed to obtain the average mass change and the average mass loss rate variation of the specimens, as shown in Fig. 8a,b. The FT cycle results in the loss of mass slate specimen, and as the number of FTC increases, so does the mass loss rate. As shown in Fig. 8, the increasing trend of the two is basically the same. According to Fig. 8b, the mass change rate of the slate specimens remains within 0.11%. Furthermore, after 30 FTC, the mass change rate of the specimens gradually decreases. Based on the test results, the reasons for the mass change of slate before and after freezing and thawing are as follows: In the process of negative temperature freezing, the water in the pores or cracks of slate will freeze and expand in volume, and the solid material in the rock will shrink when cold, resulting in the generation of frost heaving force. This force leads to the development of primary pores or cracks in the slate, and the destruction and dissolution of the cemented material and rock particles, so as to increase the porosity. During the process of positive temperature melting, the ice inside the slate melts into water, the volume becomes smaller, and the adsorption force is generated. In the process of seepage and migration of water inside the slate to form penetrating cracks, some cementing materials and rock particles will be taken away, resulting in a decrease in mass. The reason why the mass change and mass loss rate of slate tend to be gentle after 30 FTC is that at the beginning of the FT cycle, the frost heaving force inside the slate rock mass is large, and the pores or cracks inside the rock mass become larger. As the number of FTC increases, the pores or cracks within the rock mass continue to expand, and the water inside the rock can only occupy a certain part of these pores or cracks, resulting in a reduction in frost heaving force. Consequently, the effect of FTC on its mass deterioration is reduced, leading to the curve trend gradually tends to be gentle.

Longitudinal wave velocity change

Figure 9 depicts the variation trend of longitudinal wave velocity for slate specimens after 50 FTC. The figure illustrates that as the number of FTC increases, the longitudinal wave velocity shows a downward trend, and the trend is more and more gentle. The longitudinal wave velocity of slate specimens decreased on average by 3.13%, 6.14%, 8.14%, and 9.22% as the number of FTC increased to 10, 20, 30, and 50 times, respectively. The primary reason for the decrease in the longitudinal wave velocity of the specimens is that during the FT cycle, due to the participation of water, frost heaving force will be generated inside the slate, resulting in larger pores or cracks, and more air will enter the inside of the slate. Since the propagation velocity of sound wave in solid and liquid is greater than that of air, the wave velocity decreases. As the number of FTC increases, the pores or cracks inside the slate further expand, resulting in a further reduction of the longitudinal wave velocity. Since the total amount of pore water or fissure water inside the specimen is certain, further development of pores or cracks will slow down or cease. Consequently, after the slate specimen undergoes multiple FTC, the longitudinal wave velocity change will gradually flatten out. Table 2 indicates that the slate specimens exhibit relatively high density and low porosity. This suggests, to a certain extent, that the FT cycle has minimal impact on the physical properties of slate.

Mechanical tests

Stress–strain curve

Figure 10 displays the stress–strain diagrams of slate specimens under various confining pressure conditions following different FTC \(n\).

Figure 10 illustrates that the stress–strain curves of such slate specimens exhibit similar characteristics across various FTC. In order to facilitate observation, the stress–strain curve of the specimen under 0 FTC and a confining pressure of 300 kPa as the typical stress–strain curve, as shown in Fig. 11.

It can be seen from Fig. 11 that the specimens have experienced the following four different characteristic stages from loading, deformation to failure: (1) Compaction stage (0-a). As the axial load increases, the pores and fissures within the specimen gradually decrease and become more dense. The stress–strain curve will show a concave shape, reflecting the compaction process of the specimen. However, due to the small porosity and high compactness of the slate, its compaction stage is very short, which is not obvious in the stress–strain curve; (2) Elastic deformation stage (a-b). After the compaction stage, the micro-pores and micro-cracks in the slate specimen are almost completely closed, and the compactness between the particles increases. At this time, the slate specimen shows the most obvious elastic characteristics. The stress–strain curve is shown as an inclined straight line, indicating that the elastic modulus of the specimen remains essentially unchanged. The elastic deformation stage of the slate specimens used in this test is almost loaded from the beginning of the specimen to the failure stage; (3) Plastic yield stage (b-c). When the stress on the specimen exceeds the yield stress, the specimen will lose its elastic properties, and the cracks will expand and split greatly. With the interaction between the particles of the specimen, the specimen will undergo irreversible deformation, and its elastic modulus will continue to decrease. Normally, the trend of the stress–strain curve should be slow and convex. However, due to the dense pores of the slate specimen, it shows obvious brittleness, so it is not obvious from the diagram. It shows that there is no obvious sign of sudden drop in ground stress. There is almost no plastic deformation before the specimen is destroyed, indicating that the slate specimen is very brittle; (4) The destruction stage (after point c). The slate specimen loses its bearing capacity, breaks and disintegrates, the rock structure loses its integrity, and the stress–strain curve drops sharply.

In summary, the failure mode of such slate is obvious brittle fracture. After the mechanical test, most of the specimens are crushed, and the distinct failure state cannot be observed. The typical failure state of the slate specimen is shown in Fig. 12. The cracks is marked with red line, showing obvious shear failure mode.

Peak stress change curve

The peak stress of the specimens undergoing different FTC was fitted under the same confining pressure as shown in Fig. 13. The fitting results between the peak stress and the number of FTC \({\text{n}}\) of the specimen under four different confining pressures σ were obtained as follows:

-

(1)

0:

-

(2)

100 kPa:

-

(3)

200 kPa:

-

(4)

300 kPa:

The peak stress of the slate specimens under different confining pressures decreases exponentially with the increase of the number of FTC, as shown by the fitting results of the equations, and the downward trend gradually becomes more gentle. The reason for the decrease of the peak stress is the same as the reason for the decrease of its physical properties. Consequently, the trends in mass, longitudinal wave velocity, and peak stress of slate specimens become more gradual with increasing FTC.

Strength parameter analysis

In the triaxial compression test of slate, the peak stress σ1 is plotted as the ordinate and the confining pressure σ3 as the abscissa to generate the optimal relationship curve21,22 between σ1 and σ3. The cohesion and internal friction angle are calculated based on Eqs. (5) and (6), as presented in Table 3. Based on the data in Table 3, a curve diagram illustrating the relationship between the strength parameters of each group of slate specimens and the number of FTC is depicted in Fig. 14.

where \({\text{C}}\) is the cohesion (MPa), φ is internal friction angle (°), \({\sigma }_{\text{c}}\) is the intercept of the best relation curve on the ordinate, and \({\text{m}}\) is the slope of the best relation curve.

From Fig. 14, it can be seen that the cohesion of slate firstly increases and then decreases with the increase in the number of FTC and gradually tends to be gentle, while the internal friction angle and cohesion exhibit a completely opposite trend, with the variation amplitude of these two parameters becoming relatively weak and tending to be gentle after 30 FTC. During 10 FTC, the cohesion of slate reaches the maximum value of 18.81 MPa, while the internal friction angle reaches its minimum value of 68.65°. During 50 FTC, the cohesion of slate reaches its minimum value of 11.62 MPa and the internal friction angle reaches its maximum value of 74.19°.

The reason why the cohesion of the slate specimens increases first and then decreases is that the cements inside the slate recombines inside the rock during early stage of the FT cycle, resulting in a slight increase in cohesion. As the number of FTC increases, the pores and cracks in the slate expand further, and the cements and rock particles inside the rock begin to lose, so that the adhesion of the rock particles in the specimen is reduced, resulting in a sharp drop in the cohesion. The reason why the internal friction angle decreases first and then increases is that although the total volume of pores and cracks inside the slate becomes larger under FTC, no obvious penetrating cracks are observed on the surface of the specimens after different FTC, indicating that although the cementing materials, clay minerals and rock particles in the specimen are lost, most of them are re-stacked and arranged inside the slate, resulting in a larger frictional resistance between the particles inside the specimen.

Experimental study on the microstructure of slate under freeze–thaw cycle conditions

NMR tests

NMR T2 spectrum changes

The T2 spectrum of the slate specimens was obtained by using the core aperture measurement software provided by the operating computer. The T2 spectrum of a representative specimen was selected from each of the five groups of slate specimens, and the T2 spectrum of the slate specimens was obtained under various FTC, as illustrated in Fig. 15.

In the T2 spectrum, the relaxation time of the abscissa is proportional to the pore size, and the peak position of the curve correlates with the pore size, the further to the right the position, the greater the corresponding pore size. The signal amplitude of the ordinate reflects the quantity of pores across various sizes. According to the distribution pattern analysis of T2 spectrum, the T2 spectrum of slate specimens under different FT times basically has three peaks, with the first peak exhibiting a larger signal amplitude than the second and third peaks, the second peak is relatively small in height and area, and the observation of the third peak is not distinct, indicating that the number of small pores in slate is much more than that of large and medium pores. It can be observed from Fig. 15b,c that during the first 20 FTC, the first peak position gradually moves down, while the second peak position gradually moves up, indicating that the number of small pores in the specimen decreases gradually, while the number of medium pores increases, and some small pores develop into larger pores. When the specimen undergoes 30 FTC, the first peak area increases obviously and the peak position moves up obviously. Compared with the specimen subjected to 30 FTC, the first peak area and peak position of the specimen subjected to 50 FTC do not change significantly, while the second peak area increases slightly and the peak position moves up slightly. It shows that after a certain FTC, some small pores will develop into medium pores with larger pore size, and small pores will develop slowly or even no longer develop after increasing to a certain number.

It can also be observed from Fig. 15b,c that the curve shows different degrees of rightward movement. For the T2 spectrum, the abscissa moves from left to right, indicating the expansion effect FT on slate pores. On the whole, the relaxation time of the pores inside the slate becomes shorter and the relaxation speed becomes faster, the diameter of the pores inside the slate becomes larger. The change of ordinate indicates that under the FT cycle, the number of small pores increases while the number of medium pores decreases. However, due to the phase change of pore water, the size and porosity of pores after FT increase overall.

\({\text{T}}_{2}\)spectrum peak area and peak area proportion changes

The total spectrum area corresponding to the NMR relaxation time can be regarded as the porosity of slate. Therefore, the change of T2 spectrum peak area of slate specimens after different FTC can reflect the change of pore volume in slate specimens. The change pattern of the T2 spectrum peak area and the proportion of each peak after the slate specimens have undergone different numbers of FTC are shown in Table 4.

It can be seen from the Table 4 that the porosity of slate increases with the increase of FTC. The third peak is negligible compared to the first and second peaks. During the first 20 FTC, the proportion of the first peak gradually decreased, and the proportion of the second peak gradually increased, indicating that the small pores in the specimen gradually decreased and the medium pores gradually increased. After 30 FTC, the proportion of the first peak increased sharply, and the proportion of the second peak decreased sharply. Compared with 30 and 50 FTC, the proportion of the first peak decreased slightly, and the proportion of the second peak increased slightly, indicating that after 30 FTC, the small pores became more, the medium pores became less, and the pores increased to a certain number and then slowly developed or even no longer developed.

Porosity change

The core aperture measurement software of NMR instrument was utilized to measure the porosity of the slate specimens after different FTC, and the average porosity obtained is shown in Table 5, and the data in the Table 5 is drawn into Fig. 16.

From Fig. 16, it is evident that the porosity of slate specimens increases significantly as a result of repeated FTC, and the curve tends to be steep between 0 and 30 times, and then the curve tends to be gentle. The reason is that after the pores or fissures of slate specimens develop to a certain extent, the frost heaving force generated by the original pore water or fissure water in the rock under the action of FTC decreases, causing the slow or stop development of pores or fissures.

EPMA tests

The COMPO images obtained by enlarging the slate specimen with different FTC by 2000 times at the same position is shown in Fig. 17. In order to facilitate observation, the position of comparison points has been marked in the figure. From the graph, it can be observed that the surface of the slate specimen that have not undergone FTC is rough, which is related to the inherent properties of slate, showing that there are many sheet structures and sharp edges. As the number of FTC increases, the structure of the specimen deteriorates further. After 10 FTC, particle detachment is evident on the surface of the slate specimen. The surface gradually becomes smoother, and the cementitious material within the specimen is damaged. After 30 FTC, most of the characteristics of the slate surface disappeared, and the sheet structures and sharp edges could hardly be observed on the surface of the specimen. The internal structure becomes unstable, and significant enlargement of pores cannot be observed from the graph. The first reason is that ice formation during FTC generates frost heaving forces, enlarging pre-existing microcracks and pores in the slate specimen. This process weakens the bonding forces between the rock particles, exacerbating the wear and detachment of rock particles from the specimen surface, resulting in a smoother surface. The detached rock particles will rearrange and accumulate within the rock, showing a decrease of the cohesion and an increase of the internal friction angle of the slate specimen as the number of FTC increases. The second reason is that in the hydration environment of slate specimen, the FT cycle will accelerate the dissolution and collapse of rock mineral particles and cementing materials, and the presence of water will produce physical effects such as lubrication and softening on the rock, which will deteriorate its physical properties, resulting in a decrease in its mechanical properties.

Study on strength characteristics of slate based on Hoek–Brown strength criterion

Introduction of Hoek–Brown criterion

The H-B strength criterion is an empirical formula utilized for predicting rock failure. E. Hoek and E. T. Brown initially proposed the H-B criterion in 1980 during their research in underground excavation engineering18,19,20,21,22,23. Although the H-B strength criterion can be applied to all types of rocks, it is more suitable for jointed rocks such as slate, which is manifested in three aspects: first, the criterion considers the impact of joints and fractures in the rock; second, the criterion is based on extensive empirical data from jointed rocks; third, the criterion introduces the Geological Strength Index (\({\text{GSI}}\)), which can be evaluated based on the structural characteristics of the rock, such as the number and spacing of joints24,25.

In 2002, E. Hoek made improvements to the original H-B criterion and introduced relationships between \({\text{m}}_{\text{b}}\), \({\text{s}}\),\({\alpha}\) and \({\text{GSI}}\). He also introduced a new parameter \({\text{D}}\). The improved H-B strength criterion is defined as follows:

where

where \(\sigma_{1}^{{\prime }}\), \(\sigma_{3}^{{\prime }}\) represent the maximum and minimum principal stresses at rock failure, \(\sigma_{ci}\) denotes the uniaxial compressive strength of intact rock, \({\text{m}}_{\text{b}}\), \({\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\) and \({\text{s}}\) are constants of rock mass materials, depending on the rock properties.

The parameters \({\text{s}}\) and \({\alpha}\) in Eq. (7) can be calculated by the following formula:

where \({\text{D}}\) is the disturbance effect of stress release and explosion damage on rock mass. For undisturbed rock mass, \({\text{D}}\) = 0; for severely disturbed rock mass, \({\text{D}}\)=1.

In Eqs. (7) and (8), uniaxial compressive strength \(\sigma_{ci}\) and constant \({\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\) of the intact rock specimens are obtained by statistical analysis of uniaxial and triaxial test results. \(\sigma_{ci}\) and constant \({\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\) are calculated as follows:

There are slight changes to Eq. (7)

If \(\text{x} = {\upsigma}_{3}^{\prime}\) and y \(={\left({\upsigma}_{1}^{\prime}-{\upsigma}_{3}^{\prime}\right)}^{2}\), we can get

The square of the correlation coefficient is

For the special rock of slate, as long as there are no cracks on the surface and no cracks inside, it can be regarded as a complete rock specimen. In this study, the surface of the slate specimens used in the laboratory tests shows a distinct plate-like structure, and because before the mechanical tests, the NMR tests were conducted on saturated slate specimens to determine their porosity, which was found to be very small, indicating that the specimens are dense and free from cracks, so the slate specimens used in this study are considered complete.

After determining that the slate specimens used in this study are all intact specimens, the uniaxial and triaxial test results of the slate specimens under different numbers of FTC in Chapter 3 can be utilized to calculate the uniaxial compressive strength \({\upsigma}_{\text{ci}}\) and the constant \({\text{m}}_{\text{i}}\) of the slate under different numbers of FTC in accordance with Eqs. (13) and (14), respectively. Then \({\text{GSI}}\) value and \({\text{D}}\) value were determined by rock observation and field geological condition investigation and other methods, H-B criteria for slate under different FTC were established, and parameters of H-B criteria for slate under different FTC were obtained. On this basis, the regression equation of \({\upsigma}_{\text{ci}}\) with the number of FTC \({\text{n}}\) was established. Finally, the H-B empirical failure criterion describing the variation in slate strength with FTC \({\text{n}}\) was derived.

Strength characteristics test and H-B criterion of highway subgrade slate in permafrost region

According to the above ideas, using the mechanical test results in Chapter 3, Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 are the mechanical test results of slate specimens under FTC of 0, 10, 20, 30, 50 times, \({\upsigma}_{3}\) is confining pressure and \({\upsigma}_{1}\) is compressive strength.

Furthermore, since the \({\text{GSI}}\) of slate falls between 20 and 60, with higher \({\text{GSI}}\) values indicating better rock mass quality and higher strength. According to the results of a series of physical and mechanical tests conducted on the slate specimens used in this study, the \({\text{GSI}}\) value of the slate specimens is determined to be 60. The rock mass at the sampling site is undisturbed, thus the disturbance factor is taken as \({\text{D}}\) = 0. Utilizing the experimental results, the parameters of the H-B criterion for slate under different FTC are calculated using Eqs. (8) to (10), (13) and (14), respectively. Consequently, the empirical failure criteria of the H-B criterion for slate under different FTC \({\text{n}}\) are obtained:

-

(1)

n = 0

-

(2)

n = 10

-

(1)

n = 20

-

(4)

n = 30

-

(5)

n = 50

Based on the above analysis results, the parameters of the H-B criterion for slate rock mass under FTC of 0, 10, 20, 30, and 50 times can be obtained. The summary is presented in Table 11 below.

It can be concluded from Table 10 that the value of \({\text{m}}_{\text{b}}/{\upsigma}_{\text{ci}}\) in the H-B criterion parameters of slate with varying FTC ranges from 0.0862 to 0.1250, showing a small range of change. It can be seen from Eq. (7) that the value has a negligible impact on the strength of rock mass, and the parameters \({\text{s}}\) and \(\alpha\) are certain values. For the convenience of calculation, the value of \({\text{m}}_{\text{b}}/{\upsigma}_{\text{ci}}\) in H-B criterion is regarded as a certain value, that is, the parameter value of rock mass under 0 FTC is 0.0940, which has little effect on the calculation results.

Therefore, this study will perform regression analysis on the data from Table 9 to determine the relationship between the uniaxial compressive strength \({\upsigma}_{\text{ci}}\) of slate specimens and the number of FTC \({\text{n}}\), as illustrated in Fig. 18. The resulting regression equation is as follows:

Therefore, the unified expression of H-B criterion for slate rock mass in permafrost regions can be established as follows:

Conclusions

Macroscopic physical and mechanical tests and microscopic tests were conducted on slate specimens undergoing different FTC, and several conclusions were obtained:

-

Through physical and mechanical tests, it was found that the mass, longitudinal wave velocity, uniaxial compressive strength, and triaxial compressive strength of slate all decrease as the number of FTC increases. Moreover, these parameters exhibit the greatest variation between 10 to 30 FTC, after which the variation diminishes and tends to stabilize. Concerning the mechanical parameters of slate, the cohesion decreases while the internal friction angle increases as the number of FTC increases. The first 30 FTC have a significant impact on the mechanical parameters of slate, after which the trend gradually stabilizes.

-

Through the fine microscopic test, it is evident that under the action of FTC, there is a gradual increase in small pores and a corresponding decrease in medium pores in slate. However, due to water’s phase change, the porosity of slate increases as a whole, and after 30 FTC, the trend of porosity change gradually becomes gentler. Due to water's involvement, it produces frost heaving force during negative temperature freezing, and accelerate the disintegration and dissolution of rock mineral particles and cementing materials in the FT cycle. This leads to the spalling of fine particles on the surface of slate, so that the surface becomes smooth, and ultimately decreasing its physical and mechanical properties.

-

By applying the mechanical test results to the H-B strength criterion, the parameters and criterion of the H-B criterion for slate rock mass under various FTC were determined. Furthermore, through regression analysis of the experimental results, a unified expression for the H-B criterion for slate in permafrost regions was established.

Data availability

All the generated and analyzed data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Chen, X. B., Liu, J. K. & Liu, H. X. Frost Action of Soil and Foundation Engineering (Science Press, Beijing, 2006).

Wang, Q. Z., Fang, F. H. & Chao, G. Analysis of cooling effect of block-stone expressway embankment in warm temperature permafrost region. Rock Soil Mech. 41(01), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2019.0023 (2020).

Ghobadi, M. H. & Babazadeh, R. Experimental studies on the effects of cyclic freezing–thawing, salt crystallization, and thermal shock on the physical and mechanical characteristics of selected sandstones. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 48(3), 1001–1016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-014-0609-6 (2015).

Tan, X. J., Chen, W. Z., Yang, J. P. & Cao, J. J. Laboratory investigations on the mechanical properties degradation of granite under freeze–thaw cycles. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 68(3), 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2011.05.007 (2011).

Park, J., Hyun, C. U. & Park, H. D. Changes in microstructure and physical properties of rocks caused by artificial freeze-thaw action. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 74(2), 555–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-014-0630-8 (2015).

Khanlari, G., Sahamieh, R. Z. & Abdilor, Y. The effect of freeze-thaw cycles on physical and mechanical properties of upper red formation sandstones, central part of Iran. Arab. J. Geosci. 8(8), 5991–6001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-014-1653-y (2015).

Zhang, H. M. et al. Experimental research of influences of freeze-thaw cycles and confining pressure on physical-mechanical characteristics of rocks. J. China Coal Soc. 43(2), 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1322/j.cnki.jccs.2017.0098 (2018).

Bayram, F. Predicting mechanical strength loss of natural stones after freeze–thaw in cold regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 83, 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2012.07.003 (2012).

Fu, H. L. et al. Experimental study on failure types and uniaxial compressive strength of slate under low temperature freezing conditions. J. Central South Univ. Sci. Technol. 48(11), 3051–3059. https://doi.org/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7207.2017.11.028 (2017).

Du, W., Liu, Q. T. & Lin, R. S. Effects of toluene-di-isocyanate microcapsules on the frost resistance and self-repairing capability of concrete under freeze-thaw cycles. J. Build. Eng. 44, 102880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102880 (2021).

Zhou, X. P., Li, C. Q. & Zhou, L. S. The effect of microstructural evolution on the permeability of sandstone under freeze-thaw cycles. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 177, 103119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2020.103119 (2020).

Liu, Y. Q. et al. Study on strength characteristics of slate based on Hoek-Brown criterion. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 28(S2), 3452–3457 (2009).

Shi, X. C., Yang, X., Meng, Y. F. & Li, G. Modified Hoek-Brown failure criterion for anisotropic rocks. Environ. Earth Sci. 75, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-5810-3 (2016).

Eslami, J., Walbert, C., Beaucour, A. L., Bourges, A. & Noumowe, A. Influence of physical and mechanical properties on the durability of limestone subjected to freeze-thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 162, 420–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.031 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Degradation of physical and mechanical properties of sandstone subjected to freeze-thaw cycles and chemical erosion. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 155, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2018.07.007 (2018).

Li, G. X., Wang, H. L., Peng, J., Wang, L. F. & Dai, B. B. Strength model of anisotropic rocks based on Hoek-Brown criterion. Rock Soil Mech. 44(12), 3541–3550. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2023.0538 (2023).

Liu, Y. S., Fu, H. L., Rao, J. Y., Dong, H. & Zhang, H. M. Tensile strength of slate based on Heok-Brown criterion. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 35(06), 1172–1177 (2013).

Hoek, E. & Brown, E. T. Empirical strength criterion for rock masses. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 106(9), 1013–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(81)90766-x (1980).

Changjiang Academy of Science, SL/T 264-2020, Changjiang Water Resources Commission, Code for rock tests in water and hydropower projects. (Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing, 2020).

Zhongjiao Second Highway Survey and Design Institute, JTG E41-2005, Test methods of rock for highway engineering. (Ministry of Communications of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing, 2005)

Li, T., Zhao, J. J., Xie, M. L., Tan, S. Y. & Wang, G. Experimental study on the effect of slate rock mechanics properties degradation by the saturation-time. Sci. Technol. Eng. 18(6), 217–222 (2018).

Fu, X. M. & Deng, R. G. Laboratory Rock Mechaniestest (Southwest Jiaotong University Press, Sichuan, 2012).

Brown, E. T. & Hoek, E. Underground excavations in rock (CRC Press, London, 1980). https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-7952(83)90009-1.

Eberhardt, E. The Hoek-Brown failure criterion. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 45, 981–988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-012-0276-4 (2012).

Zuo, J. P. & Shen, J. Y. The Hoek-Brown Failure Criterion. The Hoek-Brown Failure criterion—From theory to application (Springer, Singapore, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1769-3.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42161026&41801046), the Science and Technology Plan Project of Qinghai Province (No. 2023-QY-206), the Youth Research Foundation of Qinghai University (No. 2022-QGY-5).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y. and Q.W.; methodology, Z.Y. and Q.W.; software, Q.W. and J.F.; validation, Q.W.; investigate, Z.Y., Q.W., J.F., K.Z., H.H. and Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, Q.W. and Z.C.; data curation, Z.Y., Q.W. and J.F.; visualization, Z.Y.; manuscript modification, Z.Y., Q.W., K.Z., H.H. and Z.C.; supervision, Q.W. and J.F.; funding acquisition, Q.W. and J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, Z., Wang, Q., Fang, J. et al. Study on physical and mechanical properties of high-grade highway subgrade slate in permafrost region under freeze–thaw cycles. Sci Rep 14, 19209 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69972-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69972-6