Abstract

Lignin syringyl to guaiacyl ratio (S/G) has long been suspected to have measurable impacts on biochar formation, but these effects are challenging to observe in biochars formed from whole biomass. When the model bioenergy feedstock Populus trichocarpa (cottonwood), with predictable lignin macromolecular structure tied to genetic variation, is used as feedstock for biochar production, these effects become visible. In this work, two P. trichocarpa variants having lignin S/G of 1.67 and 3.88 were ground and pyrolyzed at 700 °C. Water-demineralization of feedstock was used to simultaneously evaluate any synergistic influences of S/G and naturally-occurring potassium on biochar physicochemical properties and performance. The strongest effects of lignin S/G were observed on specific surface area (SBET) and oxygen-content, with S/G of 1.67 improving SBET by 11% and S/G of 3.88 increasing total oxygen content in demineralized biochars. Functional performance was evaluated by breakthrough testing in 1% NH3. Breakthrough times for biochars were nearly double that of a highly microporous activated carbon reference material, and biochar with S/G of 3.88 had 10% longer breakthrough time than its lower S/G corollary. Results support a combination of pore structure and oxygen-functionalities in controlling ammonia breakthrough for biochar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biochar is an attractive adsorbent material with high specific surface area, high micropore volume, and tunable surface chemistry which has potential as a carbon sequestration resource with far-reaching global impacts1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. It is commonly sourced from a range of waste materials including waste biomass from agricultural and timber-related activities, animal manures, and municipal sewage sludge12. This inherent feedstock flexibility comes with some challenges, however, most notably in the development of predictive models based on feedstock properties. Pyrolysis conditions account for the bulk of biochar properties; however, large variability in, for instance, hydrogen to carbon ratio or surface area is observed which could be attributed to feedstock compositional variability13,14. For biomass-based feedstocks, natural variation in properties like cellulose to lignin ratio, lignin composition, ash content, and ash composition is expected from one plant source to another14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Composition can vary even within biomass sources of the same type due to natural genetic variation, what part of the plant is used, soil type, and growing conditions15,21,22.

Lignin is the second most abundant component (10–30 wt.%) of lignocellulosic biomass after cellulose, functioning as the “glue” which holds the stiff, structural cellulose microfibrils together much like the matrix in a fiber-reinforced composite. It forms the most solid char by weight (up to 50 wt.% yield) and is therefore of great interest for optimizing char formation23. Lignin composition may strongly impact the formation of lignin pyrolytic products24,25,26. Particularly, the ratio of lignin syringyl to guaiacyl monomeric sub-units, S/G, is relevant in char formation because of the role played by methoxy moieties in formation of the critical char-forming intermediate o-quinonemethide24,27.

The impacts of lignin composition on biochar yield and properties are difficult to observe when comparing feedstocks from different sources. Previous attempts have not adequately elucidated the role of lignin composition because of large inherent differences in the comparative materials, particularly with regard to lignin monomeric subunit content19,22,24. Genetic variation in Populus trichocarpa (cottonwood), a hardwood, has been linked to predictable differences in lignin macromolecular structure, including the number and type of monomeric sub-units, content of interunit linkages, molecular weight, degree of polymerization, and lignin content16,17,21. It is proposed in the current work that S/G, on its own and as a proxy for other important lignin characteristics, has measurable effects on biochar yield and properties if these effects can be made visible through careful choice of feedstock. P. trichocarpa genetic variants with very different lignin S/G were used as a model feedstock to investigate the potential impacts of S/G on biochar yield and physicochemical properties. Dynamic adsorption in 1% ammonia was used to establish relationships between physicochemical properties and breakthrough performance.

Background

The macromolecular structure of lignin is based on three cross-linked monomeric subunits, syringyl (S), guaiacyl (G), and hydroxyphenyl (H), differentiated by the number of methoxy pendant groups (Supplemental Information Fig. S1)16. Relative content of H, S, and G varies between biomass types. For instance, switchgrass lignins have significant amounts of all three28, while hardwoods and softwoods have very low H-content compared to grasses17. Hardwood lignin has a greater percentage of S-units compared to softwood lignin, which has primarily G-units19,28. More subtle variation in H, S, and G content has been observed between genetic variants of the same species16,17,28. Lignin consists of a number of aromatic structures like phenylcoumaran, resinol, and p-hydroxy benzoate, but H, S, and G units predominate16.

Relationships between S/G and other lignin properties have been observed in P. trichocarpa16,21. Lignin S/G correlated positively with β-O-4 and β–β linkages, but a strong negative correlation was observed between S/G and β-5 linkages21,29. S/G correlated negatively with total lignin content21 but positively with lignin molecular weight17. In addition to methoxy functional groups, lignin contains a number of O- and H-rich groups, including ether-type oxygen (like β-O-4 bonds), hydroxyl-, carboxyl-, and carbonyl-related oxygen, and aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons30. Hydroxyl functional groups have low thermal stability and are likely lost through dehydration reactions, one of the primary pyrolytic processes, before char begins to form and are therefore are not likely a significant source of oxygen in biochar. Carboxyl and carbonyl groups may, on the other hand, be more thermally stable. The fate of hydrogen during pyrolysis is complicated but if not lost to fragmentation, volatilization, or gasification reactions, will migrate along the carbon skeleton as carbonization progresses31

Aromatics are key in lignin biochar formation, accounting for the high biochar yield from lignin compared to that of carbohydrate structures like cellulose32. The aromatic character of lignin decreases with increased methoxy group content, lowering the activation energy for thermal decomposition of extracted lignins33. Conversely, low-methoxy lignins have higher aromatic content and more C–C bonds between monomeric subunits, thus are more “compact” and possibly more easily carbonized33. However, methoxy functional groups provide reactive sites which may also promote carbonization24,33. Differences in primary products formation, char reactivity and coke production have been observed during pyrolysis of S and G derivatives26 that indicate feedstocks with different S/G may form char through different pathways and at different rates, impacting physicochemical properties and yield.

Lignin is known to share mechanistic synergy with naturally-occurring potassium in the formation of biochar, impacting its surface area, pore structure and surface chemistry14,20,34,35,36,37. During pyrolysis of woody biomass, potassium lowers the activation energy for thermal decomposition of plant biopolymers and catalyzes condensation reactions critical to solid char formation38,39,40,41,42. Importantly, potassium suppresses the demethylation reaction for syringyl units during pyrolysis, thus with demineralization this reaction is expected to increase38. A reduction in naturally-occurring potassium is expected to reduce biochar yield in favor of liquid products and volatiles, with the latter related to the formation of interconnected, open porosity in pyrolytic carbons14,22,38, thus, demineralization of feedstocks appears to enhance both surface area and pore volume of resulting biochar14,42,43. Relative to the more aggressive acid-based demineralization approaches, water leaching is preferred because it can remove a large percentage of naturally occurring potassium without any associated lignin structural degradation40,44. In the present work, naturally-occurring potassium was altered through water-demineralization as a means of (1) ensuring expected results were observed, and (2) probing potential synergies between lignin S/G and naturally-occurring potassium in biochar properties formation.

One of the more consequential attributes of biochar is the ubiquitous presence of oxygenated functional groups. Oxygen functionalities offer favorable sites for chemisorption of ammonia molecules, and function in conjunction with accessible surface area in determining quasi-static ammonia adsorption capacity9,10,45. Lactonic, phenolic, and carboxylic functional groups were observed to improve ammonia adsorption in activated biochars46. Since quasi-static adsorption capacity is directly related to dynamic adsorption capacity, oxygen groups should play a similar role in extending breakthrough times47. Surface area may be less important than oxygen content in biochar dynamic adsorption of very low concentrations of gaseous ammonia45,48,49,50.

Populus trichocarpa as a model feedstock

Two P. trichocarpa variants study with very different S/G were chosen for the present study, BESC-316 and CHWH-27–2, having S/G of 1.67 and 3.88, respectively. These two materials were previously characterized by others16,21, with relevant compositional parameters reported in Table 1.

The greatest impact of increasing S/G on interunit linkages in any biomass may be a reduction in the β-β-type C–C bonds associated with the presence of both S and G units29. The content of β-O-4 bonds between S and G units, and β-β, and β-5 C–C linkages was 9% greater, 82% lower, and 19% lower, respectively, for CHWH-27–2 compared to BESC-316. Uncondensed structures are formed by β-O-4 linkages29, therefore BESC-316, with a higher percentage of C–C bonds, is more condensed. An increase in β-O-4 bonds increases the reactivity of the lignin during pyrolysis and may increase oxygen content51. Conversely, C–C linkages have greater thermal stability, and, particularly in absence of naturally-occurring potassium which would catalyzed cracking-type reactions, may increase the yield, aromaticity, and reduce the final oxygen content of the biochar.

Glucan content is 11.5% higher and lignin content is 16.3% lower for CHWH-27-2 compared to BESC-316, while the difference in S/G is 132%. The inherent uncertainty of the measurement for biopolymer content was not reported in21, but standard deviation for all P. trichocarpa variants utilized in reference16 is low, therefore there is confidence in these values. It is proposed in this present work that for whole, untreated biomass, the differences in polysaccharide and phenylpropanoid content are minor compared to, for instance, comparison of a herbaceous feedstock28 and a hardwood or even a softwood and a hardwood52.

Results and discussion

Demineralization of biomass

Naturally-occurring potassium was successfully removed by water demineralization of the ground biomass (Table S2). Potassium decreased by more than 89%, and sodium was almost completely removed. Water demineralization was less successful with Ca and Mg, removing up to 39% and 45%, respectively.

During pyrolysis of woody biomass, potassium lowers the activation energy for thermal decomposition of plant biopolymers and catalyzes condensation reactions critical to solid char formation, resulting in enhanced production of gaseous and solid products38,39,40,41,42. A reduction in naturally-occurring potassium, either by acid- or water-washing, was expected to reduce biochar yield in favor of liquid products and volatiles, with the latter related to the formation of interconnected, open porosity in pyrolytic carbons14,22,38,42,53. Demineralization of feedstocks has also been observed to increase the oxygen content of biochars14. These expected effects were tracked in the appropriate sections below as a function of potassium content to validate experimental methods in gauging the effects of lignin S/G, as well as investigating any synergistic effects between lignin S/G and naturally-occurring potassium content.

Thermal gravimetric analysis

Thermal gravimetric studies provided insight into the moisture, ash, volatile carbon, and recalcitrant carbon content, as well as decomposition behavior, and chemistry of biochars. Characteristic differences were observed based on S/G and demineralization (Supplemental Information Table S3).

Demineralization reduced the ash content (Table S3) in BESC-316-based biochars, BC-B and BC-BL40, by approximately half (1.91% wt. to 1.02% wt., respectively). Similarly, the reduction for CHWH-27-2-based biochars, BC-C and BC-CL40, was ⁓60% wt. (2.44% wt. to 0.94% wt., respectively). BC-C contained more inorganics than BC-B, while for BC-CL40 and BC-BL40 inorganics content was roughly equivalent. Demineralized biochars lost more weight between 450 and 1000 °C (in inert environment) compared to untreated biochars (Fig. 1), which can be accounted for by the catalytic action of potassium in untreated feedstock promoting char-forming reactions. Moisture content was lower for demineralized biochars, but no trend for moisture was observed for S/G. The relative quantity of recalcitrant carbon increased with demineralization alone, however no trends for volatile carbon were observed.

DTG curves for all biochars, shown in Fig. 1, reveal that above ⁓450 °C, the rate of mass loss for demineralized chars increased significantly compared to untreated chars. This result will be discussed in the following section.

Effusion of CO2 and H2

Gaseous species are produced during thermal decomposition as carbonization progresses. CO2 and H2 are produced from oxygenated and hydrogenated surface species, consistent with the hydrogen- and oxygen-rich functional groups of biochar, thus can be used to interpret biochar composition. Assignment of oxygenated functional group origins for CO2 was made according to Szymanski et al.54, validated by diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) spectra. CO2 and H2 MS ion currents and DTG curves are shown in Fig. 2 for each biochar. Effusion of CO2 at approximately 120 °C was attributed to surface-adsorbed atmospheric CO2. Production began in earnest at approximately 450 °C, and between 450 and 750 °C the first of two maxima in CO2 effusion was observed, attributed to decomposition of carboxylic anhydride and lactone groups on the primary char. The second maximum, observed between 750 and 950 °C, is attributed to ether and pyrone structures on the primary char. BC-CL40 produced the most intense CO2 ion current, indicating high S/G may enhance oxygen-content. The greater CO2 effusion of demineralized chars compared to untreated chars is consistent with higher O-content14,42. Even naturally-occurring K can lower the activation energy for thermal decomposition of lignocellulosic feedstock, catalyze condensation reactions, and increase the production of gaseous products, particularly CO2, possibly through catalysis of gasification reactions38,39,40,41,42. The overall effect is reduction of oxygenated species in the solid biochar from untreated feedstock.

H2 effusion began above 700 °C in all materials. Untreated biochars showed a broad peak at 800 °C, while this peak was much lower intensity for demineralized chars. All biochars exhibited a sharp increase in H2 production above 900 °C. Demineralized biochars produced a greater increase in intensity above 900 °C compared to untreated materials, consistent with differences in H-mobility during carbonization or in the chemical environment of hydrogen31.

In amorphous carbons such as biochars, interpretation of hydrogen effusion is complicated by its relationship to carbon structure, to catalytic action of inorganics, particularly K and Ca, and to gasification reactions which may produce hydrogen31,55,56. Hydrogen originates from C–H in both sp2 and sp3 hydrocarbons, and during pyrolysis it migrates along the carbonaceous skeleton as carbonization and reorganization processes proceed31. BC-CL40 shows the highest H2 production near 1000 °C, much higher than the original pyrolysis temperature (700 °C), which suggests a possible link between high S/G, demineralization, and high-temperature carbonization behavior.

In Fig. 2, the DTG curves from Fig. 1 are reproduced to aid in interpretation of ion current data. Demineralized biochars showed higher rates of thermal decomposition above 450 °C. Between 450 and 800 °C this increase roughly corresponds to an increase in CO2 effusion. Above 800 °C, however, CO2 effusion drops off. H2 production alone is unlikely to account for the increased rate of mass loss. Instead, this increase at high temperatures is attributed to products of thermal cracking processes with increased carbonization and production of heavier polyaromatic hydrocarbons57,58.

H/C as an indicator of aromaticity

Atomic hydrogen to carbon ratio (H/C) has been identified by Xiao et al. as a simple indicator of biochar aromaticity13. H/C for all biochars (Table S3) ranged from 0.4 to 0.5, which are somewhat high compared to other 700 °C biochars13. This result is attributed to the very short dwell time at HTT. Within the error of the H/C calculation procedure, there was no apparent link to H/C based on S/G or demineralization. This result is supported by the Raman results discussed further on. It is likely, then, that H/C, or aromaticity, is not dependent on lignin S/G or K-content of feedstocks but may have variation based on other feedstock parameters.

Diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS)

DRIFTS was used to semi-quantitatively validate the presence of oxygen- and hydrogen-containing functional groups. Raw, vertically-shifted DRIFTS spectra for all biochars and the reference activated carbon are shown in Fig. 3a, while the background-subtracted, normalized fingerprint region for only the biochars are shown in Fig. 3b to highlight the presence of oxygenated functional groups. In Fig. 3b, all spectra were normalized to the maximum at 1585 cm−1, the aromatic ring C=C stretch, based on the observation that all materials contain roughly the same H/C and the same density of 6-member rings59, as evidenced by identical I(D)/I(G) reported in Table 2. The Norit RB3 measurement was used to determine how its oxygen-content compared to that of the biochars, aiding in the interpretation of ammonia breakthrough curves.

The normalized spectra from the four biochars were quite similar, most notably regarding intensity related to carbonyl groups (1690 cm−1) and C–O groups (1300–1000 cm−1).

The low intensity in the O–H stretch region (3000–4000 cm−1) in Fig. 3a for all materials indicates little to no physically adsorbed water and an absence of –O–H functional groups, ruling out the presence of phenolic and carboxylic acid groups. This observation does not, however, rule out anhydrides that will participate in ammonia chemisorption9,10,48.

The fingerprint region in Fig. 3a shows important characteristic differences in oxygen-containing surface chemistry between the biochars and the activated carbon (Norit RB3) with implications for ammonia adsorption. In Fig. 3b, the C=O conjugated lactone/quinone stretch at 1690 cm−1, the aliphatic ether C–O–C mode at 1050–1000 cm−1 and aromatic ether mode 1300–1210 cm−1 are observed in the spectra of all biochars. These groups were not observed in the spectrum of Norit RB. The normalized C=O peak at 1690 cm−1 is most intense for BC-CL40.

Raman spectroscopy

The dominant features of the Raman spectra (Fig. 4) for all biochars, the so-called D and G bands, occur in the first-order region between 1000 and 1800 cm−1. D and G band integral sub-peaks have been previously fitted using a number of physically meaningful models59,60,61. Comparative Raman curves for biochars and Norit RB3 are shown in Fig. S3. The low, broad second-order region, characteristic of amorphous carbons, implies limited and highly disordered 3D stacking of aromatic ring structures62,63. In this present work, the concepts of Ferrari and Robertson59 have been employed to fit the first-order band between 1000 and 2000 cm−1 with two functions and a linear background64,65,66. Resulting fitted parameters, listed in Table 2, were used comparatively. More information on fitting parameters is found in the Supplemental Information.

Ratios of the peak heights from each of the fitted D and G bands were used to infer information about the structural arrangements (relative degree of amorphous character) of the biochar carbon skeletons. The relative intensity of the D and G bands, I(D)/I(G), is an indicator of aromatic ring clustering in amorphous carbons59. I(D)/I(G) was equivalent for all biochars, indicating neither S/G nor K-content is determinant of the size of aromatic ring clusters. It is more likely that HTT is deterministic of I(D)/I(G), and I(D)/I(G) was much lower for biochar than for the activated carbon Norit RB3, consistent with a more highly carbonized structure expected in the latter (Fig. S3).

The position of the G-band (Pos(G)) was found to be consistent for all materials, including Norit RB3. A Pos(G) near or above 1600 cm−1 indicates linear sp2 chains are present in the material59.

The full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the G-band is also relevant to biochar structure. The narrower FWHM(G) for BC-C (75 cm−1 compared to 81 cm−1 for other biochars) indicates in increase in order of sp2 carbon phases which could manifest as either larger or less defected clusters of aromatic rings, or more order in linear sp2 chains63. BC-C was prepared from the feedstock with high K-content and high S/G, implicating some synergy between the two feedstock parameters in determining carbonization behavior.

Specific surface area and porosity

The results of volumetric N2 adsorption were used to assess the role of S/G in the development of porosity and nitrogen-accessible surface area, and also to understand the potentially competing roles of oxygen-content and pore volume and surface area on dynamic ammonia adsorption in biochars. Results are listed in Table 2.

SBET also showed a strong dependence on naturally-occurring K-content, consistent with the findings of others14,40. Demineralized chars have approximately four hundred times greater SBET compared to the untreated biochars.

Lignin S/G trended negatively with SBET in demineralized chars, with BC-BL40 showing 11% greater SBET than BC-CL40. According to the fundamentals of pore formation in pyrolytic carbons, and consistent with the work of others26, it is possible this result could be attributed to enhanced formation of volatiles favored by low S/G feedstock.

Pore formation is initiated during pyrolysis as gases and volatiles escape the bulk, leaving behind voids. Open pores are formed when volatiles and gases escape efficiently from the bulk, exposing the spaces between aromatic layers (micropores) to larger connecting channels (mesopores) which subsequently open to macropores or to the surface67. If volatiles are not able to efficiently exit the bulk, they can clog pathways out of the structure, resulting in closed porosity and very low accessible surface area68.

Somewhat counterintuitively, for demineralized chars, high methoxy group content should result in more cross-linking among intermediate products following homolysis of methoxy groups, which may reduce volatiles production by way of enhanced secondary reactions between volatile species and the char skeleton26,69. The result should be a reduction in N2-accessible surface area for high S/G materials, which was indeed observed in this present work. Based on the high significance of this result, more studies with P. trichocarpa variants are merited to determine the magnitude of any correlation between S/G and pore volume and SBET over a range of HTT.

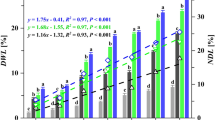

Dynamic ammonia adsorption

Breakthrough curves for ammonia uptake by the four biochars and Norit RB3 are shown in Fig. 5. Full breakthrough curves for representative experiments are shown in the Supplemental Information, Fig. S6. The curves in Fig. 5 represent the average of three breakthrough trials for each material, having a width of two standard deviations on the mean. Mean breakthrough times for C/C0 = 0.10 and C/C0 = 0.01 for all materials are reported in Table 3.

Biochar performed better than Norit RB3 in ammonia breakthrough tests. BC-B, BC-BL40, BC-C and BC-CL40 had 78%, 110%, 97%, and 115% and 131%, 185%, 146%, and 177% increase in mean breakthrough time compared to Norit RB3 at C/C0 = 0.10 and C/C0 = 0.01, respectively.

Among biochars alone, demineralization and lignin S/G both correlated strongly with ammonia breakthrough. Mean breakthrough time for BC-BL40 was 18% and 23% longer than BC-B at C/C0 = 0.10 and C/C0 = 0.01, respectively, and mean breakthrough time for BC-CL40 was 9% and 13% longer than BC-C at C/C0 = 0.10 and C/C0 = 0.01, respectively. For untreated biochars, BC-C had 10% longer mean breakthrough time compared to BC-B at C/C0 = 0.10, but only 7% increase in mean breakthrough time at C/C0 = 0.01. BC-B and BC-C showed similar specific surface areas (Table 2) but had very different lignin S/G contents (1.67 and 3.88, respectively). It is proposed that these differences in breakthrough time are attributed to different oxygen chemistries at the particle surfaces and macropores.

Breakthrough time did not correlate with SBET when all materials were considered collectively (R2 = 0.535 and 0.546 for C/C0 = 0.01 and 0.10, respectively), shown graphically in Fig. 6a. For instance, SBET for Norit RB3 was approximately 103 times that of BC-C, however the breakthrough time for Norit RB3 (6.0 s) was approximately half that of BC-C (11.8 s) at C/C0 = 0.10. Norit RB3, BC-BL40, and BC-CL40 are microporous (Supplemental Information Fig S5). The poor correlation between SBET and breakthrough time suggests that high micropore surface area alone is not deterministic of ammonia breakthrough performance. However, when only the biochars were considered, breakthrough time showed a positive correlation with SBET at both C/C0 = 0.01 and 0.10 (R2 = 0.7540 and 0.9366, respectively). This relationship is shown in Fig. 6b.

Microporosity in carbon-based adsorbents is typically attributed to slit-like pores associated with misaligned clusters of aromatic rings. The weak correlation between SBET and breakthrough time indicates that high N2-accessible micropore surface area, and thus carbon structure, is not responsible for adsorption up to breakthrough.

The poor correlation with micropore surface area indicates that another factor, most likely surface chemistry, is driving breakthrough time, and specifically, the chemistry of outer surfaces and macropores. Lodewyckx and Wood noted that for chemisorption, micropore volume may be less important than chemical interactions between the contaminant and active sites in activated carbons49. Huang et al. and Domingo-Garcia et al. found that surface area, particularly that associated with micropores, was not the governing factor in determining breakthrough behavior of ammonia on oxidized activated carbons due to the prevalence of acidic oxygen-containing groups at the entrances to micropores45,48.

For large particles, such as granules or rods, breakthrough is dominated by boundary layer diffusion70,71. For particles on the order of ⁓150 µm, as in this study, intraparticle diffusion is expected to determine the overall dynamic adsorption rate71. Because microporosity was not correlated to breakthrough time, differences in surface chemistry can be interpreted as driving the observed behavior.

The presence of surface acid sites, evidenced by DRIFTS band between 1750 and 1650 cm−1 (Fig. 3b) for all biochars, indicate carboxylic anhydrides, pyrone, quinone, or lactone species on the surface of biochar particles are likely to be involved in adsorption up to breakthrough. These bands are noticeably absent from or have very low intensity in the DRIFTS spectrum of Norit RB3 (Fig. 3a). Weak acid groups would readily take up ammonia via chemisorption during the initial stages of the dynamic adsorption process, but restrict further access to micropore surface area if located at the edges to micropores. Domingo-Garcia et al. observed this latter phenomenon for oxidized activated carbons48. Thus, for oxygenated species located within pores, access would be limited on short time scales associated with breakthrough. Because microporosity did not correlate to breakthrough time, differences in surface chemistry can be interpreted as driving the observed behavior.

Conclusions

It was originally proposed that with the use of P. trichocarpa genetic variants having very different S/G, any impacts of whole biomass lignin S/G on biochar physicochemical properties and yield could be observed. The significance of the results suggests further work with additional P. trichocarpa variants of intermediate S/G be done for validation. Observed impacts of S/G may be directly related to S/G, that is, having to do with the activity of the methoxy moieties during pyrolysis reactions, or indirectly related to S/G due to important correlations between S/G and other lignin properties like interunit linkages and aromaticity.

S/G of 3.88 with untreated feedstock increased the ordering of sp2 carbon phases, apparent in reduced Raman G-band FWHM. Demineralized biomass with S/G of 3.88 produced the highest CO2 effusion, attributed to anhydride carboxylic and lactonic functional groups during secondary heating in a TGA, followed by demineralized, S/G = 1.67 biochar, with untreated biochars producing the least CO2 effusion. It is concluded that high S/G in demineralized chars contain higher levels of -COO functional groups. Demineralization reduced H-production at ~ 700 °C during secondary heating in a TGA, while S/G of 3.88 enhanced high-temperature H-production (at T > 800 °C), implying high S/G may impact crosslinking within sp3 carbon phases.

When isolated from the catalytic effects of potassium through water demineralization, biochar with S/G of 1.67 showed higher SBET by 11% and improved biochar yield by 4% compared to biochar with S/G of 3.88.

Untreated biochar with S/G of 3.88 had longer mean ammonia breakthrough times by 10% compared to untreated biochar with S/G of 1.67. Both untreated and demineralized biochar from the S/G 3.88 feedstock had longer mean breakthrough times than their low S/G corollaries. Specific surface area alone was not deterministic in dynamic ammonia adsorption when all materials were considered. However, when biochars alone were considered, a positive trend between SBET and breakthrough time was observed. From this it is concluded that while oxygenated surface groups are required for strong ammonia breakthrough performance by biochars, this performance can be improved through enhanced micropore volume.

Methods

Feedstock materials

Two unique P. trichocarpa genetic variants, named BESC-316 and CHWH-27-2, were used as biochar feedstocks based on the large difference in respective ratios of lignin S to G groups (S/G)16,17. Lignin was previously characterized by Yoo et al.21 and those findings are reported in Table 1, including some previously unreported biopolymer values presented here with permission.

Feedstock and biochar preparation

As-received chips of BESC-316 and CHWH-27-2 P. trichocarpa genetic variants were ground and sieved to ⁓ 2 mm. Untreated, sieved biomass is labelled as BESC-316 and CHWH-27-2, the names of the genetic variants received from ORNL, from here on. A portion of each was demineralized, or leached, in milli-Q water, filtered and dried under ambient conditions for 24 h, then at 70 °C for 48 h. Demineralized biomass is labelled as L-BESC-316 and L-CHWH-27–2 from here on.

Biochar was prepared by pyrolysis of biomass at 15 °C/min. to 700 °C, with a 5-min dwell, and then cooled at \(\sim\) 5 °C/min. under flowing argon (3.0 L/min.). All biochars were ground and sieved to ⁓150 µm. A commercial activated carbon, Norit RB3, was used as a microporous, high-surface area reference material for dynamic ammonia adsorption. The Norit RB3 was received in granulated form, but was ground and sieved to ⁓150 µm. Biochar and activated carbon sample names and descriptions are reported in Table 4.

Characterization methods

Ultimate analysis of untreated and demineralized biomass was conducted according to ASTM E871, ASTM D1102, CEN/EN 15104 and CEN/EN 15289.

Biomass ash was produced according to NREL/TP-510-42622. AAEM composition of the ash was quantified by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) according to EPA Method 200.7.

Biochar proximate analysis was conducted by thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA), with volatile carbon accounted for by the method of Mitchell et al.72 The effusion of thermal decomposition products of biochars TGA in UHP Ar were monitored by electron impact quadrupole mass spectrometer (MS). H/C was quantified through calibration of H2O and CO2 ion current peak areas from TGA-MS of calcium oxalate monohydrate, in 90% UHP O2/balance UHP Ar73,74.

DRIFTS measurements were taken with samples diluted to \(\sim\) 7% wt./wt. in KBr powder with a KBr reference under ambient conditions. At least three spectra from each material were collected to test for sample homogeneity.

Raman scattering measurements were taken on undiluted materials, using a 20 × LWD objective and 514 nm emission line from an argon ion laser at 30 μW power and 5 µm spot size. For each material, measurements were taken at 3 randomly chosen places to test for sample homogeneity.

Nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms were measured at 75.9 K between 10−4 and 100 kPa using an automated volumetric instrument. The samples were degassed at 130 °C under oil-free vacuum to 10–6 kPa for 4 h prior to measurements. Specific surface area was calculated by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method between the lowest partial pressure and the maximum in the Rouquerol plot75. Total pore volume was calculated by the single-point method at P/P0 = 0.9576.

Dynamic ammonia adsorption (breakthrough testing)

For dynamic adsorption, or ‘breakthrough’, experiments, biochars were dried at 75 °C for 48 h prior to testing. For each test, 0.5 g of adsorbent was placed in a 15 mm diameter quartz column in a custom apparatus. The packed column was purged for 2 h in flowing UHP N2 (90 ml/min) at room temperature prior to starting the test. Total volumetric flow was 100 ml/min (90 ml/min. N2, 10 ml/min. 90% He/10% NH3) with ammonia concentration set to 1% by volume. Effluent NH3 was measured by MS, tracking m/z = 17. The flow of ammonia was shut off after approximately 60 s to limit ammonia exposure in the mass spectrometer. Breakthrough curves were corrected by subtracting the dead volume response at 1% and 10% inlet concentration, C/C0 = 0.01 and 0.10, respectively, from the corresponding points on the averaged curve for each material.

Data availability

Datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lehmann, J., Gaunt, J. & Rondon, M. Bio-char sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems: A review. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 11, 403–427 (2006).

Liu, W.-J., Jiang, H. & Yu, H.-Q. Development of biochar-based functional materials: Toward a sustainable platform carbon material. Chem. Rev. 115, 12251–12285 (2015).

Woolf, D., Amonette, J. E., Street-Perrott, F. A., Lehmann, J. & Joseph, S. Sustainable biochar to mitigate global climate change. Nat. Commun. 1, 1–9 (2010).

Cheng, S., Chen, X., Hsuan, Y. G. & Li, C. Y. Reduced graphene oxide-induced polyethylene crystallization in solution and nanocomposites. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma2021453

Uchimiya, M., Wartelle, L. H. & Boddu, V. M. Sorption of triazine and organophosphorus pesticides on soil and biochar. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 2989–2997 (2012).

Park, J. H., Choppala, G. K., Bolan, N. S., Chung, J. W. & Chuasavathi, T. Biochar reduces the bioavailability and phytotoxicity of heavy metals. Plant Soil 348, 439–451 (2011).

Alozie, N., Heaney, N. & Lin, C. Biochar immobilizes soil-borne arsenic but not cationic metals in the presence of low-molecular-weight organic acids. Sci. Total Environ. 630, 1188–1194 (2018).

Lehmann, J. A handful of carbon. Nature 447, 143–144 (2007).

Wang, B., Lehmann, J., Hanley, K., Hestrin, R. & Enders, A. Adsorption and desorption of ammonium by maple wood biochar as a function of oxidation and pH. Chemosphere 138, 120–126 (2015).

Hestrin, R., Enders, A. & Lehmann, J. Ammonia volatilization from composting with oxidized biochar. J. Environ. Qual. 49, 1690–1702 (2020).

Agyarko-Mintah, E. et al. Biochar lowers ammonia emission and improves nitrogen retention in poultry litter composting. Waste Manag. 61, 129–137 (2017).

Ghodake, G. S. et al. Review on biomass feedstocks, pyrolysis mechanism and physicochemical properties of biochar: State-of-the-art framework to speed up vision of circular bioeconomy. J. Clean. Prod. 297, 126645 (2021).

Xiao, X., Chen, Z. & Chen, B. H/C atomic ratio as a smart linkage between pyrolytic temperatures, aromatic clusters and sorption properties of biochars derived from diverse precursory materials. Sci. Rep. 6, 22644 (2016).

Bourke, J. et al. Do all carbonized charcoals have the same chemical structure? 2. A model of the chemical structure of carbonized charcoal. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 46, 5954–5967 (2007).

Keiluweit, M., Nico, P. S., Johnson, M. G. & Kleber, M. Dynamic molecular structure of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 1247–1253 (2010).

Dumitrache, A. et al. Consolidated bioprocessing of Populus using Clostridium (Ruminiclostridium) thermocellum: A case study on the impact of lignin composition and structure. Biotechnol. Biofuels 9, 31 (2016).

Yoo, C. G. et al. Significance of lignin S/G ratio in biomass recalcitrance of Populus trichocarpa variants for bioethanol production. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 2162–2168 (2018).

Mészáros, E. et al. Do all carbonized charcoals have the same chemical structure? 1. Implications of thermogravimetry-mass spectrometry measurements. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 46, 5943–5953 (2007).

Wang, S. et al. Comparison of the pyrolysis behavior of lignins from different tree species. Biotechnol. Adv. 27, 562–567 (2009).

Cagnon, B., Py, X., Guillot, A., Stoeckli, F. & Chambat, G. Contributions of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin to the mass and the porous properties of chars and steam activated carbons from various lignocellulosic precursors. Bioresour. Technol. 100, 292–298 (2009).

Yoo, C. G. et al. Insights of biomass recalcitrance in natural Populus trichocarpa variants for biomass conversion. Green Chem. 19, 5467–5478 (2017).

Asmadi, M., Kawamoto, H. & Saka, S. Pyrolysis reactions of Japanese cedar and Japanese beech woods in a closed ampoule reactor. J. Wood Sci. 56, 319–330 (2010).

Cao, J., Xiao, G., Xu, X., Shen, D. & Jin, B. Study on carbonization of lignin by TG-FTIR and high-temperature carbonization reactor. Fuel Process. Technol. 106, 41–47 (2013).

Hosoya, T., Kawamoto, H. & Saka, S. Role of methoxyl group in char formation from lignin-related compounds. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 84, 79–83 (2009).

Hosoya, T., Kawamoto, H. & Saka, S. Pyrolysis gasification reactivities of primary tar and char fractions from cellulose and lignin as studied with a closed ampoule reactor. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 83, 71–77 (2008).

Asmadi, M., Kawamoto, H. & Saka, S. Thermal reactions of guaiacol and syringol as lignin model aromatic nuclei. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 92, 88–98 (2011).

Cheng, H., Wu, S., Huang, J. & Zhang, X. Direct evidence from in situ FTIR spectroscopy that o-quinonemethide is a key intermediate during the pyrolysis of guaiacol. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 409, 2531–2537 (2017).

David, K. & Ragauskas, A. J. Switchgrass as an energy crop for biofuel production: A review of its ligno-cellulosic chemical properties. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1182 (2010).

Kishimoto, T. et al. Influence of syringyl to guaiacyl ratio on the structure of natural and synthetic lignins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58, 895–901 (2010).

Eswaran, S., Subramaniam, S., Sanyal, U., Rallo, R. & Zhang, X. Molecular structural dataset of lignin macromolecule elucidating experimental structural compositions. Sci. Data 9, 647 (2022).

Conway, N. M. J. et al. Defect and disorder reduction by annealing in hydrogenated tetrahedral amorphous carbon. Diam. Relat. Mater. 9, 765–770 (2000).

Zheng, Q., Li, Z., Yang, J. & Kim, J.-K. Graphene oxide-based transparent conductive films. Prog. Mater. Sci. 64, 200–247 (2014).

Li, W. et al. Linking lignin source with structural and electrochemical properties of lignin-derived carbon materials. RSC Adv. 8, 38721–38732 (2018).

Eom, I.-Y.Y. et al. Characterization of primary thermal degradation features of lignocellulosic biomass after removal of inorganic metals by diverse solvents. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 3437–3444 (2011).

Fahmi, R. et al. The effect of alkali metals on combustion and pyrolysis of Lolium and Festuca grasses, switchgrass and willow. Fuel 86, 1560–1569 (2007).

Mcdonald-Wharry, J., Manley-Harris, M. & Pickering, K. Carbonisation of biomass-derived chars and the thermal reduction of a graphene oxide sample studied using Raman spectroscopy. Carbon N. Y. 59, 383–405 (2013).

Nan, H. et al. Interaction of inherent minerals with carbon during biomass pyrolysis weakens biochar carbon sequestration potential. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 1591–1599 (2019).

Eom, I.-Y. et al. Effect of essential inorganic metals on primary thermal degradation of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 104, 687–694 (2012).

Fan, H. et al. Effect of potassium on the pyrolysis of biomass components: Pyrolysis behaviors, product distribution and kinetic characteristics. Waste Manag. 121, 255–264 (2021).

LeBrech, Y. et al. Effect of potassium on the mechanisms of biomass pyrolysis studied using complementary analytical techniques. ChemSusChem 9, 863–872 (2016).

Nowakowski, D. J., Jones, J. M., Brydson, R. M. D. & Ross, A. B. Potassium catalysis in the pyrolysis behaviour of short rotation willow coppice. Fuel 86, 2389–2402 (2007).

Raveendran, K., Ganesh, A. & Khilar, K. C. Influence of mineral matter on biomass pyrolysis characteristics. Fuel 74, 1812–1822 (1995).

Raveendran, K. Pyrolysis characteristics of biomass and biomass components. Fuel 75, 987–998 (1996).

Jiang, L. et al. Influence of different demineralization treatments on physicochemical structure and thermal degradation of biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 146, 254–260 (2013).

Huang, C. C., Li, H. S. & Chen, C. H. Effect of surface acidic oxides of activated carbon on adsorption of ammonia. J. Hazard. Mater. 159, 523–527 (2008).

Zhu, F. et al. Efficient adsorption of ammonia on activated carbon from hydrochar of pomelo peel at room temperature: Role of chemical components in feedstock. J. Clean. Prod. 406, 137076 (2023).

Verhoeven, L. & Lodewyckx, P. Using the Wheeler–Jonas equation to describe adsorption of inorganic molecules: Ammonia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268012563

Domingo-García, M., Groszek, A. J., López-Garzón, F. J. & Pérez-Mendoza, M. Dynamic adsorption of ammonia on activated carbons measured by flow microcalorimetry. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 233, 141–150 (2002).

Lodewyckx, P., Wood, G. O. & Ryu, S. K. The Wheeler–Jonas equation: A versatile tool for the prediction of carbon bed breakthrough times. Carbon N. Y. 42, 1351–1355 (2004).

Ro, K., Lima, I., Reddy, G., Jackson, M. & Gao, B. Removing gaseous NH3 using biochar as an adsorbent. Agriculture 5, 991–1002 (2015).

Huang, Y. et al. Association of chemical structure and thermal degradation of lignins from crop straw and softwood. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 134, 25–34 (2018).

Ahmad, Z., Al Dajani, W. W., Paleologou, M. & Xu, C. Sustainable process for the depolymerization/oxidation of softwood and hardwood kraft lignins using hydrogen peroxide under ambient conditions. Molecules 25, 2329 (2020).

Gray, M. R., Corcoran, W. H. & Gavalas, G. R. Pyrolysis of a wood-derived material. Effects of moisture and ash content. Ind. Eng. Chem. Process Des. Dev. 24, 646–651 (1985).

Szymanski, G. S. et al. The effect of the gradual thermal decomposition of surface oxygen species on the chemical and catalytic properties of oxidized activated carbon. Carbon N. Y. 40, 2627–2639 (2002).

Safar, M. et al. Catalytic effects of potassium on biomass pyrolysis, combustion and torrefaction. Appl. Energy 235, 346–355 (2018).

Yao, D. et al. Hydrogen production from biomass gasification using biochar as a catalyst/support. Bioresour. Technol. 216, 159–164 (2016).

Akhtar, J. & Amin, S. A review on operating parameters for optimum liquid oil yield in biomass pyrolysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 5101–5109 (2012).

Horne, P. A. & Williams, P. T. Influence of temperature on the products from the flash pyrolysis of biomass. Fuel 75, 1051–1059 (1996).

Ferrari, A. C. & Robertson, J. Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 61, 14095–14107 (2000).

Li, X., Hayashi, J. & Li, C. FT-Raman spectroscopic study of the evolution of char structure during the pyrolysis of a Victorian brown coal. Fuel 85, 1700–1707 (2006).

Smith, M. W. et al. Structural analysis of char by Raman spectroscopy: Improving band assignments through computational calculations from first principles. Carbon N. Y. 100, 678–692 (2016).

Cançado, L. G. et al. Measuring the degree of stacking order in graphite by Raman spectroscopy. Carbon N. Y. 46, 272–275 (2008).

Ferrari, A. C. Raman spectroscopy of graphene and graphite: Disorder, electron–phonon coupling, doping and nonadiabatic effects. Solid State Commun. 143, 47–57 (2007).

Muretta, J. E., Prieto-Centurion, D., LaDouceur, R. & Kirtley, J. D. Unique chemistry and structure of pyrolyzed bovine bone for enhanced aqueous metals adsorption. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 14, 703–722 (2022).

Goettlich, D., Hadi, A., McEnaney, K. & Kirtley, J. D. Investigations of biochar as a tunable platform for aqueous malathion adsorption and decomposition. MRS Adv. 6, 759–763 (2021).

McGlamery, D., Baker, A. A., Liu, Y.-S., Mosquera, M. A. & Stadie, N. P. Phonon dispersion relation of bulk boron-doped graphitic carbon. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 23027–23037 (2020).

Tomczyk, A., Sokołowska, Z. & Boguta, P. Biochar physicochemical properties: Pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 19, 191–215 (2020).

Brewer, C. E. et al. New approaches to measuring biochar density and porosity. Biomass Bioenergy 66, 176–185 (2014).

Zhang, H. et al. Mechanism study on the interaction between holocellulose and lignin during secondary pyrolysis of biomass: In terms of molecular model compounds. Fuel 244, 107701 (2023).

Crittenden, J. C., Trussell, R. R., Hand, D. W., Howe, K. J. & Tchobanoglous, G. MWH’s Water Treatment: Principles and Design: Third Edition. MWH’s Water Treat. Princ. Des. Third Ed. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118131473

Rehrmann, J. A. & Jonas, L. A. Dependence of gas adsorption rates on carbon granule size and linear flow velocity. Carbon N. Y. 16, 47–51 (1978).

Mitchell, P. J., Dalley, T. S. L. & Helleur, R. J. Preliminary laboratory production and characterization of biochars from lignocellulosic municipal waste. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 99, 71–78 (2013).

Huang, Y. F., Kuan, W. H., Chiueh, P. T. & Lo, S. L. Pyrolysis of biomass by thermal analysis–mass spectrometry (TA–MS). Bioresour. Technol. 102, 3527–3534 (2011).

Aso, H., Matsuoka, K. & Tomita, A. Quantitative analysis of hydrogen in carbonaceous materials: Hydrogen in anthracite. Energy Fuels 17, 1244–1250 (2003).

Rouquerol, J., Rouquerol, F., Llewellyn, P., Maurin, G. & Sing, K. S. W. Adsorption by Powders and Porous Solids: Principles, Methodology and Applications: Second Edition. Adsorpt. by Powders Porous Solids Princ. Methodol. Appl. Second Ed. (Academic Press Inc., 2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/C2010-0-66232-8

Gregg, S. & Sing, K. S. W. Adsorption, Surface Area and Porosity (Academic Press, 1982).

Acknowledgements

The authors would especially like to thank Dr. Wellington Muchero (Oak Ridge National Lab, Biosciences Division) for biomass, and Dr. Arthur Ragauskas (University of Tennessee), Dr. Chang Geun Yoo (SUNY-Syracuse), and Oak Ridge National Lab for allowing us to report their biomass compositional data. Additional thanks to Giovanna Luciano, Dr. Jerome Downey (Montana Technological University), the Center for Advanced Materials Processing (CAMP – Montana Technological University), Dr. Nicholas Stadie (Montana State University), Dr. Alysia Cox (Montana Technological University), Eva Barahona (Montana Technological University), and Ashley Huft (Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology) for access to instrumentation and technical support in this research. We also thank our research sponsor. Research was sponsored by the Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Laboratory and was accomplished under Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-20-2-0163. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Laboratory or the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Roles/Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing; J.U.: Data curation, Roles/Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing; D.C.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Roles/Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing; R.L.: Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing; J.K.: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Resources, Writing—review and editing; D.P.: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muretta, J.E., Uriarte, J., Compton, D. et al. Effects of lignin syringyl to guaiacyl ratio on cottonwood biochar adsorbent properties and performance. Sci Rep 14, 19419 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70186-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70186-z