Abstract

Nanofibers show promise for wound healing by facilitating active agent delivery, moisture retention, and tissue regeneration. However, selecting suitable dressings for diverse wound types and managing varying exudate levels remains challenging. This study synthesized carbon quantum dots (CQDs) from citrate salt and thiourea using a hydrothermal method. The CQDs displayed antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. A nanoscaffold comprising gelatin, chitosan, and polycaprolactone (GCP) was synthesized and enhanced with silver nanoparticle-coated CQDs (Ag-CQDs) to form GCP-Q, while citrate addition yielded GCP-QC. Multiple analytical techniques, including electron microscopy, FT-IR spectroscopy, dynamic light scattering, UV–Vis, photoluminescence, X-ray diffraction, porosity, degradability, contact angle, and histopathology assessments characterized the CQDs and nanofibers. Integration of CQDs and citrate into the GCP nanofibers increased porosity, hydrophilicity, and degradability—properties favorable for wound healing. Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed accelerated wound closure with GCP-Q and GCP-QC compared to GCP alone. Overall, GCP-Q and GCP-QC nanofibers exhibit significant potential for skin tissue engineering applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The skin acts as the primary defense against threats from the outside world. It has the ability to heal and renew itself after getting hurt. However, delays in the healing process can lead to severe harm or death. Slow-to-heal wounds present a major challenge for healthcare systems globally. At the same time, finding ways to speed up wound healing is an important clinical objective1. Wound treatments are tailored based on wound pathology, size, and details. Traditional approaches focus on managing therapeutic factors like infection control, mechanical protection, and nutrition2. For treatment-resistant, poorly responsive, or severely traumatized wounds, surgical intervention and skin grafting are often needed. Autografts using the patient's skin are limited in availability. Allografts from donor skin and xenografts from other species can provoke unwanted immune reactions3. Tissue-engineered skin substitutes have emerged as promising new alternatives to traditional wound healing approaches4.

Regenerative medicine and tissue engineering have emerged as promising strategies to address tissue and organ loss. Tissue engineering involves three key components: cells, signaling molecules, and three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds. Advancing each component is critical for the success of tissue engineering approaches5,6.

Engineered skin was the first successfully lab-grown and commercialized organ7. Many engineered skin substitutes now exist commercially or in trials8. However, reliable substitutes fully replicating normal skin remain lacking. As a result, researchers worldwide aim to address challenges and develop more effective therapies closely replicating skin structures to treat skin diseases and wounds9,10,11. Among the newer emerging technologies, the use of nanoscale materials has gained more attention due to the flexibility in design and exceptional properties that can address dysfunctions associated with wound healing. Numerous nanotechnology-driven therapies utilizing nanomaterials and nanoscaffolds now target different wound repair phases12,13.

Nanofibers are promising scaffolds that are widely used for tissue engineering and are mainly fabricated through the electrospinning process14. Defined as fibers of 1–1000 nm, the nanofiber diameter definition has extended to 1000 nm as interesting biological effects occur in this range. For example, antimicrobial properties manifest in polymers at ≤ 400 nm fibers, showing important biological effects from 100 to 1000 nm15,16. The high porosity, surface area, and interconnected pore network of nanofibers enable optimal cell seeding, vascularization, matrix production, oxygen/nutrient transfer, and fluid drainage at wounds while restricting bacterial penetration. These characteristics provide many benefits, making nanofibers an ideal scaffold material for wound healing applications5,17. The ability to select polymers from natural or synthetic sources with biocompatible properties expands the potential applications of nanofibers in wound care18. The flexibility of the electrospinning process enables polymers to be co-electrospun with various therapeutic agents19.

A variety of natural (e.g. collagen, gelatin, chitosan) and synthetic (e.g. polycaprolactone, polyurethane) polymer matrices are used in tissue engineering and wound healing. Synthetic polymers have favorable mechanical properties and tunable degradation profiles but may lack inherent biological signals found in natural extracellular matrix components, important for promoting optimal wound healing20. Additionally, the degradation of certain synthetic polymers, like PLGA, can generate uncontrolled, strong acidic byproducts that may disrupt the local wound environment and impede healing21,22. On the other hand, natural polymers have inherent bioactivity and biocompatibility but lack mechanical strength23. Given the strengths and weaknesses of synthetic and natural polymers, combinations of these polymers are often used as temporary dressings for epidermal and dermal grafts and wounds24,25. The complementary properties of the two polymer types are leveraged when they are blended, providing scaffolds with tunable bioactivity, biocompatibility, degradation, and mechanics. These polymer blends can be fabricated into scaffolds using methods like electrospinning and 3D printing26.

Nanoparticles (NPs) are another group of compounds utilized in tissue engineering and wound healing research today. These particles range in size from 1 to 100 nm and have a high surface-to-volume ratio. Nanoparticles can be classified based on their properties, shapes, or dimensions27. Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) are zero-dimensional nanoparticles under 10 nm with unique stability, biocompatibility, optical properties, and ability to stimulate angiogenesis. CQDs also have anti-bacterial, anti-oxidant, and low toxicity characteristics, while being inexpensive and chemically inert28. Combining traditional wound healing agents with CQDs may provide new solutions for chronic wound care challenges29.

Wound pH transitions from alkaline to neutral to acidic during healing. An acidic environment promotes healing by increasing antibacterial activity, reducing infection and bacterial products, modulating protease activity, improving oxygen release, and enhancing epithelization and vascularization. Topical application of acids like ascorbic and citric acid has shown positive therapeutic outcomes on wounds30.

In this study, we electrospun a biodegradable nanofiber scaffold using a blend of natural and synthetic polymers (chitosan, gelatin, and polycaprolactone) to create a wound-healing dressing. We then incorporated CQDs (and citrate into the electrospun scaffolds to enhance wound healing capacity. The physicochemical properties of the fabricated scaffolds were characterized and their wound-healing functions were evaluated in an animal model.

Materials and methods

Materials

The chemicals used were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, except where stated otherwise. The Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) strains were purchased from the Pasteur Institute of Iran. Double distilled water was used as the solvent in all experiments.

Synthesis of silver nanoparticle-coated CQDs (Ag-CQDs)

To prepare safe, cheap, and non-toxic CQDs, we used citrate and thiourea as carbon sources. The CQDs were synthesized using the hydrothermal method as described by Omidi et al.31. Briefly, 2 gr tri-ammonium citrate, 0.1 g thiourea, and 75 ml distilled water were mixed and magnetically stirred until clear. The mixture was put into an autoclave and heated at 175 °C for 6 h. After cooling to room temperature, the undissolved particles were filtered out through a 0.2-micron filter, and the filtrate CQDs were kept at 5 ± 3 °C.

The Ag-CQDs were prepared using the chemical reduction method. For this purpose, 3.0 ml of CQDs and 1.0 ml of 0.01 M AgNO3 were mixed with 0.05 g of a potent reducing agent of sodium borohydride32. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 3 h. The obtained yellow solution of Ag-CQDs nanocomposites was stable for nearly 1 month when kept at 5 ± 3 °C.

Anti-bacterial activity of Ag-CQDs

The antibacterial properties of CQDs and Ag-CQDs were evaluated using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC). The Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli were used for this purpose. The MIC test is performed by preparing a series of dilutions of the antimicrobial agents (CQDs and Ag-CQDs) and inoculating them with the microorganism. The lowest concentration of the antimicrobial agent that inhibits the visible growth of the microorganism is considered the MIC. The MBC test is performed by taking the samples from the MIC test and inoculating them onto agar plates. The lowest concentration of the antimicrobial agent that results in a 99.9% reduction in the number of viable bacterial colonies compared to the growth control is considered MBC.

Fabrication of electrospun nanofiber

To fabricate the basic nanofiber containing chitosan, gelatin, and polycaprolactone, the solutions of 35% (w/v) gelatin and 2% (w/v) chitosan were prepared separately in a 50% (v/v) acetic acid solvent. While polycaprolactone was dissolved at a concentration of 14% (w/v) in a 3:1 mixture of chloroform and dimethylformamide. The gelatin-chitosan solution (70:30 ratio) was blended with 0.1 M citrate buffer, pH 4.5 (85:15 ratio). AgNPs-coated CQDs (Ag-CQDs) were incorporated at an equivalent volume to the citrate buffer. The electrospinning process was conducted based on a previously reported protocol33,34. The gelatin-chitosan, Ag-CQD, and citrate solution were electrospuned from a 1.2 mm diameter needle at 0.3 mL/h flow rate, 19 kV voltage, and 10 cm tip-to-collector distance. Simultaneously, the polycaprolactone solution was electrospuned from a parallel 0.8 mm diameter needle at 1 mL/h, 25 kV, and 10 cm distance. Electrospinning was performed at 25 ± 1 °C and 45% relative humidity using a dual-syringe pump system. Three scaffold compositions were produced: (I) the basic scaffold containing chitosan, gelatin, and polycaprolactone (GCP), (II) the basic scaffold improved with Ag-CQDs (GCP-Q), and, (III) the GCP-Q improved with citrate (GCP-QC).

Physicochemical properties of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), CQDs, and Ag-CQDs

The size and morphology of the AgNPs were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and TEM with high-resolution (HRTEM) using a Philips CM120 microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands) operating at an acceleration voltage of 120 kV.

The average hydrodynamic diameter and particle size distribution of CQDs were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Nanophox 90-246V instrument (Sympatec GmbH, Germany). The polydispersity index (PDI) was calculated to quantify the broadness of the CQD size distribution according to the following equation35;

where σ represents the standard deviation of the particle size distribution, and d is the mean hydrodynamic diameter. A larger PDI value indicates a broader distribution of particle sizes, meaning the sample has a wider range of diameters.

The optical properties of the synthesized CQDs and Ag-CQDs were characterized by ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy. UV–Vis absorption spectra were acquired over a range of 200–600 nm using a RayLeigh UV-2601 spectrophotometer (Beijing RayLeigh Corp., China). PL emission spectra were obtained from 246 to 396 nm using an Avaspec-2048 TEC spectrometer (Avantes BV, Netherlands). The chemical composition of the CQDs and Ag-CQDs was analyzed by Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy over a wavenumber range of 650–4000 cm−1. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were acquired using an STOE STADV diffractometer (STOE, Darmstadt, Germany) to determine structural properties.

Electrospun nanofiber degradation and porosity

Degradation kinetics of electrospun scaffolds were determined by mass loss. Scaffolds were cut into 1 cm × 1 cm squares, measured for initial dry mass (W0), and incubated in both 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 5, or pH 7.5 at 37 °C. At 8, 20, 44, 92, and 164-h time points, samples were removed, dried, and weighed (Wt). Percent mass loss was calculated as:

The porosity of electrospun GCP, GCP-Q, and GCP-QC scaffolds was quantified using a liquid displacement method with ethanol36. Scaffolds were measured for dry mass (Wd) and then immersed in ethanol to obtain wet mass (Ww). Submerged scaffold mass (Wl) was also determined. Percent porosity was calculated as:

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), fourier transform infrared (FTIR), and contact angle analysis

The morphology of electrospun nanofibers was characterized by SEM using a Hitachi Su 3500 microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), and fiber diameters were measured from micrographs using ImageJ software v1.52 (https://imagej.net).

The chemical composition of GCP, GCP-Q, and GCP-QC nanofibers was analyzed by FTIR on a Thermo Nicolet spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Spectra were acquired over 650–4000 cm−1 wavenumbers.

The wettability of GCP, GCP-Q, and GCP-QC nanofibers was determined by sessile drop contact angle measurements. Droplets were dispensed onto nanofiber mats using a micropipette and imaged using a Sony digital camera. Contact angles were quantified from images using ImageJ software v1.52.

Histology

The efficacy of electrospun GCP, GCP-Q, and GCP-QC nanofibers for wound healing was evaluated in a murine model. For histological studies, three female rats with a weight of 200–250 g and an age of approximately 8 weeks were used for each group. Dorsal hair was removed and 0.5 cm2 full-thickness excisional wounds were generated. The surface of the wounds was then covered with GCP, GCP-Q, and GCP-QC with an area of 1.25 cm2, and fixed with a bandage. Wound restoration was evaluated on days 4, 8, and 12 post-wounding Skin sections encompassing wounds were excised and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and 5 μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). All experimental protocols were approved by the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee (IR, SBMU.RETECH.REC.1395.291), and all methods and experiments in this study were performed following relevant guidelines and regulations. We confirm that this study was reported in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines for reporting animal research.

Results

The anti-bacterial potential of AgNPs-coated CQDs

The results indicated that coating with Ag-NPs increases the MIC and MBC of CQDs against a gram-negative (Escherichia coli) and a gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) are shown in Table 1. Both CQDs and Ag-CQDs exhibited similar antibacterial efficacy against both the gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial strains tested.

DLS measurement and TEM

The average size and width of CQDs and Ag-CQD were determined using the DLS pattern (Fig. 1A,B). The PDI values of CQDs and Ag-CQD were 0.66 and 0.56, respectively (Table 2), indicating a monodisperse distribution with uniform nanoparticle dispersion in solution. TEM and HRTEM images of the synthesized CQDs (Fig. 1C,D) revealed spherical particles with an average diameter of approximately 7 nm that were evenly distributed without aggregation.

UV–Vis and PL adsorption

UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy of the CQDs (Fig. 2A) showed two sharp peaks at 226 nm and 281 nm, corresponding to π–π* transitions of C=C bonds and n–π* transitions of C=O groups, respectively. The Ag-CQDs displayed a surface plasmon resonance peak at 430 nm, which arises from the collective oscillation of conduction electrons in the silver electrons in the AgNPs upon interaction with incident light37. The absence of the peaks at 226 and 281 nm in the UV–Vis absorption spectrum of the Ag-CQDs can be attributed to several factors related to the interaction between the AgNPs and CQDs. These include the strong surface plasmon resonance peak that overshadows them, potential quenching effect due to energy transfer to AgNPs, and changes in the electronic environment of CQDs38. The photoluminescence excitation spectrum of the CQDs from 246 to 396 nm resulted in an emission peak centered at 500 nm regardless of excitation wavelength (Fig. 2B), indicating wavelength-independent emission behavior for the CQDs. The strong UV absorption of the CQDs is attributed to π–π* transitions of aromatic phenyl rings and C=C bonds present in the quantum dots.

FTIR and XRD studies

The chemical structures of CQDs and Ag-CQDs were characterized by FTIR spectroscopy. The FTIR spectrum of the CQDs (Fig. 3A, green) exhibited a broad peak at 3333 cm−1 attributed to overlapping N–H and O–H stretches, and a medium peak at 1635 cm−1 corresponding to C–O vibrations. A weak peak was observed around 2000 cm−1 due to C–C vibrations. In the Ag-CQD spectrum (Fig. 3A, red), previously observed peaks at 3333 cm−1, and 1635 cm−1 were confirmed. Additionally, weak peaks at 2061 cm−1, 1449 cm−1, and 1324 cm−1 were detected, associated with C≡C stretching, C=C stretching, and C–O stretching vibrations, respectively. XRD analysis confirmed the presence of crystalline silver planes on the CQDs. The XRD pattern of the nanocomposites (Fig. 3B) displayed four distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 38°, 44°, 65°, and 78°, corresponding to the (111), (200), (220), and (311) planes of crystalline silver, indicating the successful formation of AgNPs on the CQD surfaces.

SEM of electrospun GCP, GCP-Q, and GCP-QC nanofibers

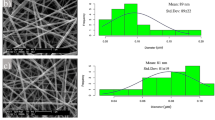

SEM imaging revealed fibrous, porous structures for the GCP, GCP-Q, and GCP-QC nanofibers (Fig. 4). The GCP fibers exhibited diameters ranging from 25 to 300 nm, with a predominant distribution at 225 nm. The GCP-Q fibers showed a similar diameter range of 25–300 nm, but with a slightly reduced modal diameter of 175 nm. The GCP-QC fibers also spanned 25–300 nm diameters, with a further reduced modal diameter of 150 nm. The incorporation of Ag-CQDs decreased fiber diameter compared to GCP, with additional reduction occurring upon the addition of citrate, from a predominant 225 nm for GCP down to 125 nm for GCP-QC. This decrease in nanofiber thickness is significant, as it would be expected to increase the hydrolysis rate of the nanofibers.

FTIR characterization of electrospun GCP, GCP-Q, and GCP-QC nanofibers

FTIR spectroscopy was used to characterize the GCP, GCP-Q, and GCP-QC nanofibers (Fig. 5). The GCP spectrum (red) displayed peaks at 3300 cm−1 and 2850 cm−1 corresponding to O–H and C–H stretches, respectively. The peak at 1650 cm−1 was attributed to C=O vibrations, while peaks at 2080 cm−1, 1150 cm−1, and 1200 cm−1 were associated with C=C, C–C, and C–O vibrations, respectively. Additional peaks at 600 cm−1 and 720 cm−1 corresponded to C–H vibrations, and a peak at 1490 cm−1 was due to N–H vibrations. These primary peaks were observed in all fiber spectra. Incorporation of CQDs was evidenced by the appearance of a distinct C–O vibration peak at 1300 cm−1 in the GCP-Q spectrum (green) that was much weaker for GCP. However, the C=C vibration peak at 1750 cm−1 was absent in the GCP-Q sample, likely indicating bonding between polymer amine/carbonyl groups and CQD hydroxyls on the nanofiber surface. For GCP-QC (blue), the C=C peak at 1750 cm−1 was very weak, while new peaks at 1399 cm−1 and 1600 cm−1 associated with citrate C=O vibrations appeared, confirming the presence of citrate. The C–C and C–O peaks at 1100 cm−1 and 1300 cm−1 also increased slightly in intensity. The observed FTIR spectral changes indicate the successful incorporation of citrate and Ag-CQDs into the nanofibers via chemical bonding, suggesting citrate acts as a reducing agent for AgNP synthesis.

Degradation rate, porosity, and contact angle of fabricated nanofibers

Degradation studies were performed in PBS at pH 7.5 and 5.0 by monitoring sample weight loss over time. The results demonstrated increased degradation rates for GCP-Q and GCP-QC compared to GCP at both pH conditions (Fig. 6A,B), indicating the incorporation of Ag-CQDs and citrate enhanced degradation. Porosity was assessed using liquid displacement, revealing 85%, 87%, and 88% porosity for GCP, GCP-Q, and GCP-QC scaffolds, respectively (Fig. 6C). These high porosity values with uniform, interconnected pores are advantageous for nutrient and oxygen absorption and waste removal during wound healing. Contact angle measurements showed the GCP nanofibers were hydrophobic with a contact angle of 107° (Fig. 6D). Incorporation of Ag-CQDs and citrate significantly increased hydrophilicity, reducing the contact angle to 67° for GCP-Q (Fig. 6E) and 53° for GCP-QC (Fig. 6F).

Histological study

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was utilized to evaluate collagen deposition and tissue morphology during wound healing. Healthy collagen stained blue while damaged collagen appeared red. Histological analysis (Fig. 7) revealed greater neutrophil infiltration in GCP-treated wounds compared to GCP-Q and GCP-QC, indicating enhanced antibacterial activity of the nanoparticle-containing scaffolds. After 4 days, GCP-QC treated wounds exhibited accelerated collagen accumulation. By day 8, neutrophil levels decreased in GCP-Q and GCP-QC but persisted in GCP samples, with visible hair follicles. At 12 days post-treatment, infectious cells remained elevated in GCP wounds but were significantly reduced with GCP-Q and GCP-QC. Furthermore, GCP-Q and GCP-QC yielded complete re-epithelialization with a thin epidermal layer, unlike GCP. Overall, the histological data demonstrates superior wound healing performance with GCP-Q and GCP-QC compared to GCP alone, likely due to their antibacterial properties and improved collagen deposition.

Discussion

Electrospun nanofibers show promise for advanced wound dressings owing to their biodegradability, ease of fabrication, and tunable thickness. They can promote cell migration, reduce inflammation, and relieve pain through controlled medication release39. Their high porosity enables proper oxygen, moisture, and nutrient exchange without damaging the wound40.

Gelatin, derived from collagen, provides a biocompatible and biodegradable matrix that supports cell attachment and proliferation. Among polymers used for electrospinning nanofibers, this natural polymer is significant for creating nanofibrous mats for wound healing. In vivo tests showed electrospun gelatin nanofibers loaded with vitamins A and E were more effective for wound healing than commercially used antiseptic gauze and films41. Gelatin is water-soluble, but gelatin/water solutions have poor electrospinnability, generating low-quality nanofibers due to strong hydrogen bonding42,43. Using acetic acid as a gelatin solvent improves electrospinnability. Mixing gelatin with other biopolymers to make hybrid nanofibers also enhances electrospun gelatin properties44.

In this study, we employed gelatin-based nanofibers with low concentrations of chitosan and polycaprolactone as co-mixing substrates in an acetic acid solvent, aiming to harness the synergistic benefits of these components for wound healing. Chitosan, derived from chitin, has antimicrobial properties and promotes wound healing through hemostatic and immune-modulating effects45. Polycaprolactone is a synthetic polymer with favorable biological properties and mechanical strength suitable for wound healing applications46. Chitosan's antimicrobial properties can prevent infection, while PCL's mechanical strength provides support and protection at the wound site. This combination may enable a scaffold that promotes wound healing and reduces inflammation. Using a low 15% acetic acid concentration allows electrospinning of uniform nanofibers with increased hydrophobicity, biodegradability, and potential for tissue engineering applications47,48.

Bacterial infection is a major problem that can prolong wound healing and cause chronic non-healing wounds. Bacteria release toxins that reduce fibroblast and epithelial cell proliferation, impair cell function, and destroy cells49,50. Antibiotic resistance has created controversy over indiscriminate antibiotic use in wound care51. As a result, alternative antibacterial biomaterials such as wound dressings are used to enhance healing. In addition to utilizing the superior antibacterial properties of chitosan, we sought to simultaneously leverage the benefits of CQDs and AgNPs. To achieve this, we designed a novel CQD particle that was coated by AgNPs. CQDs have inherent antibacterial properties and have been reported to possess strong antibacterial activities against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Previous studies have shown that combining CQDs with other antimicrobial reagents can enhance their antibacterial activity52. Here, we found that the addition of AgNPs to the CQDs improved its antibacterial efficiency against both the gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative Escherichia coli bacteria. AgNPs have been shown to cause oxidative stress, protein dysfunction, membrane disruption, and DNA damage in bacteria, however, the exact mechanism underlying the bactericidal activity of AgNPs remains to be fully elucidated53,54. Furthermore, the incorporation of Ag-CQDs and trisodium citrate led to a significant reduction in the average diameter of electrospun nanofibers. There are several factors that may contribute to this observation. First, citrate and Ag-CQDs function as reducing agents, resulting in the formation of smaller AgNPs that disrupt chain entanglement55,56. Additionally, they may modify the viscoelastic properties of the polymer solution and improve its electrical conductivity, which facilitates better fiber stretching38. Finally, they can affect the rates of solvent evaporation, leading to quicker solidification of the polymer jet57. In wound healing applications, smaller nanofiber diameters provide several benefits, including a higher surface area to volume ratio, faster hydrolysis of the scaffold, improved collagen deposition and re-epithelialization, and the capacity to mimic the native tissue environment58,59.

In addition to enhancing porosity and degradability, the addition of Ag-CQDs and trisodium citrate boosted the hydrophilicity properties of nanofiber. Hydrophilic dressings can improve the moisturizing properties of the wound bed60. A moist wound environment created by hydrophilic dressings facilitates autolytic debridement, which is the process of using the body's endogenous enzymes to break down and remove dead tissue from the wound bed. This process helps to promote faster and better quality of healing61.

Most of the pathogenic bacteria associated with infected wounds in humans need a pH value > 6, and their growth is inhibited by lower pH values. Chemical acidification of wounds has been shown to be an adjuvant to healing which makes the environment unfavorable for bacterial growth62. Here, we used citrate buffer with pH 4.5 as one of the nanofiber compounds. Citrate buffer is a safe chemical that has been used in wound healing due to its ability to modulate wound pH to an acidic environment, which has been shown to promote wound healing62,63. Wounds treated topically with citric acid buffer solutions were observed to have a significantly higher rate of wound closure. For example, Tandon et al. indicated that wounds treated with citric acid showed an average reduction in wound size of 73.43% by the 14th day as compared to 66.52% in the control group63. The observed reduced neutrophil penetration in the GCP-Q and GCP-QC treated wound compared to the basic GCP-treated one, suggests that Ag-CQDs and citrate play an antibacterial role in the wound site. The study found that wounds treated with GCP-QC had faster collagen fiber accumulation, and the epidermal layer formed on the wound treated with GCP-Q and GCP-QC was thin and completely covered the surface of the wound, while GCP did not. These findings suggest the positive effects of adding synthesized Ag-CQDs and citrate buffer to GCP dressing in promoting wound healing process. The histological findings remain to be more analyzed and quantified in molecular levels in the future.

Conclusion

The study investigated the potential of GCP nanofiber mats for skin wound healing, improved by the incorporation of Ag-CQDs and trisodium citrate. The addition of Ag-CQDs and trisodium citrate to the GCP nanofiber mats resulted in improved hydrophilicity, wettability, and degradability, which are crucial for effective wound healing. Histopathological examination showed that the GCP-Q and GCP-QC nanofiber mats had better wound-healing outcomes than the GCP nanofiber mats alone, suggesting that the combination of gelatin, chitosan, polycaprolactone, Ag-CQDs, and trisodium citrate may create a scaffold with promoted wound-healing properties and reduced inflammation. The enhanced properties of the fabricated nanofiber mates (GCP-Q and GCP-QC) make them a promising alternative to traditional wound dressing and scaffolds.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Landén, N. X., Li, D. & Ståhle, M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: A critical step during wound healing. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 3861–3885 (2016).

Nourian Dehkordi, A., Mirahmadi Babaheydari, F., Chehelgerdi, M. & Raeisi Dehkordi, S. Skin tissue engineering: Wound healing based on stem-cell-based therapeutic strategies. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 10, 1–20 (2019).

Chen, M., Przyborowski, M. & Berthiaume, F. Stem cells for skin tissue engineering and wound healing. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 37, 399–421 (2009).

Andreadis, S. T. Gene transfer to epidermal stem cells: Implications for tissue engineering. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 4, 783–800 (2004).

Chaudhari, A. A. et al. Future prospects for scaffolding methods and biomaterials in skin tissue engineering: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1974 (2016).

Chen, M. et al. Biochemical stimulus-based strategies for meniscus tissue engineering and regeneration. Biomed. Res. Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8472309 (2018).

Vacanti, C. The history of tissue engineering. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 1, 569–576 (2006).

Vig, K. et al. Advances in skin regeneration using tissue engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 789 (2017).

Boyce, S. T., Lalley, A. L. Tissue engineering of skin and regenerative medicine for wound care. Burn. Trauma 6, (2018).

Mohamed, A. & Xing, M. M. Nanomaterials and nanotechnology for skin tissue engineering. Int. J. Burns Trauma 2, 29–41 (2012).

Savoji, H., Godau, B., Hassani, M. S., Akbari, M. Skin tissue substitutes and biomaterial risk assessment and testing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 6, (2018).

Hamdan, S. et al. Nanotechnology-driven therapeutic interventions in wound healing: Potential uses and applications. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 163–175 (2017).

Chakrabarti, S., Chattopadhyay, P., Islam, J. & Ray, S. Aspects of nanomaterials in wound healing. Curr. Drug Deliv. 16, 26–41 (2019).

Adams, W. W., Eby, R. K. High-Performance and Specialty Fibers XIII–451 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55203-1.

Destaye, A. G., Lin, C. K. & Lee, C. K. Glutaraldehyde vapor cross-linked nanofibrous PVA mat with in situ formed silver nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 4745–4752 (2013).

Cooper, A., Floreani, R., Ma, H., Bryers, J. D. & Zhang, M. Chitosan-based nanofibrous membranes for antibacterial filter applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 92, 254–259 (2013).

Jun, I., Han, H. S., Edwards, J. R. & Jeon, H. Electrospun fibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering: viewpoints on architecture and fabrication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 745 (2018).

Liu, Y., Zhou, S., Gao, Y. & Zhai, Y. Electrospun nanofibers as a wound dressing for treating diabetic foot ulcer. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 14, 130–143 (2019).

Luraghi, A., Peri, F. & Moroni, L. Electrospinning for drug delivery applications: A review. J. Control. Release 334, 463–484 (2021).

Reddy, M. S. B., Ponnamma, D., Choudhary, R. & Sadasivuni, K. K. A comparative review of natural and synthetic biopolymer composite scaffolds. Polym. 13, 1105 (2021).

Rhee, S. H. & Seung, J. L. Effect of acidic degradation products of poly(lactic-co-glycolic)acid on the apatite-forming ability of poly(lactic-co-glycolic)acid-siloxane nanohybrid material. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 83, 799–805 (2007).

Sung, H. J., Meredith, C., Johnson, C. & Galis, Z. S. The effect of scaffold degradation rate on three-dimensional cell growth and angiogenesis. Biomaterials 25, 5735–5742 (2004).

Chan, J. M. W. et al. Chemically modifiable N-heterocycle-functionalized polycarbonates as a platform for diverse smart biomimetic nanomaterials. Chem. Sci. 5, 3294–3300 (2014).

Chiono, V., Pulieri, Æ. E. & Vozzi, Æ. G. Genipin-Crosslinked Chitosan/Gelatin Blends for Biomedical Applications 889–898 (2008) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-007-3212-5.

Gautam, S., Amit, C. C. & Dinda, K. Fabrication and characterization of PCL/gelatin/chitosan ternary nanofibrous composite scaffold for tissue engineering applications. J. Mater. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-013-7785-8 (2014).

Romero-Araya, P. et al. Combining materials obtained by 3D-printing and electrospinning from commercial polylactide filament to produce biocompatible composites. Polymers (Basel). 13, 1–19 (2021).

Khan, I., Saeed, K. & Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 12, 908–931 (2019).

Yaqoob, A. A. et al. Recent advances in metal decorated nanomaterials and their various biological applications: A review. Front. Chem. 8, 1–23 (2020).

Praseetha, P. K., Vibala, B. V., Sreedevy, K. & Vijayakumar, S. Aloe-vera conjugated natural Carbon Quantum dots as Bio-enhancers to accelerate the repair of chronic wounds. Ind. Crops Prod. 174, 114152 (2021).

Nagoba, B. S., Selkar, S. P., Wadher, B. J. & Gandhi, R. C. Acetic acid treatment of pseudomonal wound infections—A review. J. Infect. Public Health 6, 410–415 (2013).

Omidi, M., Yadegari, A. & Tayebi, L. Wound dressing application of pH-sensitive carbon dots/chitosan hydrogel. RSC Adv. 7, 10638–10649 (2017).

Amjadi, M. et al. Facile synthesis of carbon quantum dot/silver nanocomposite and its application for colorimetric detection of methimazole. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 244, 425–432 (2017).

Guo, Z. et al. In vitro evaluation of random and aligned polycaprolactone/gelatin fibers via electrospinning for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 26, 989–1001 (2015).

He, X. et al. Electrospun gelatin/PCL and collagen/PLCL scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering. Int. J. Nanomed. 9, 2335–2344 (2014).

Obiedallah, M. M., Abdel-Mageed, A. M. & Elfaham, T. H. Ocular administration of acetazolamide microsponges in situ gel formulations. Saudi Pharm. J. 26, 909–920 (2018).

Simorgh, S. et al. Human olfactory mucosa stem cells delivery using a collagen hydrogel: As a potential candidate for bone tissue engineering. Materials (Basel). 14, 1–17 (2021).

Ghorghi, M. et al. Electrospun captopril-loaded PCL-carbon quantum dots nanocomposite scaffold: Fabrication, characterization, and in vitro studies. Polym. Adv. Technol. 31, 3302–3315 (2020).

Cotrim, M. & Oréfice, R. Biocompatible and fluorescent polycaprolactone/silk electrospun nanofiber yarns loaded with carbon quantum dots for biotextiles. Polym. Adv. Technol. 32, 87–96 (2021).

Chen, K. et al. Recent advances in electrospun nanofibers for wound dressing. Nanomedicine 12, 1335–1352 (2017).

Rahimi, M. et al. Carbohydrate polymer-based silver nanocomposites: Recent progress in the antimicrobial wound dressings. Carbohydr. Polym. 231, 3913–3931 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Electrospun gelatin nanofibers loaded with vitamins A and e as antibacterial wound dressing materials. RSC Adv. 6, 50267–50277 (2016).

Sajkiewicz, P. & Kolbuk, D. Electrospinning of gelatin for tissue engineering-molecular conformation as one of the overlooked problems. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 25, 2009–2022 (2014).

Duconseille, A., Astruc, T., Quintana, N., Meersman, F. & Sante-Lhoutellier, V. Gelatin structure and composition linked to hard capsule dissolution: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 43, 360–376 (2015).

Li, T., Sun, M. & Wu, S. State-of-the-art review of electrospun gelatin-based nanofiber dressings for wound healing applications. Nanomaterials 12, 784 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Chitosan-based hydrogels for infected wound treatment. Macromol. Biosci. 2300094, 1–12 (2023).

Raina, N., Pahwa, R. & Khosla, J. K. Polycaprolactone-based materials in wound healing applicationsitle. Polym. Bull. 79, 7041–7063 (2022).

Erencia, M. et al. Electrospinning of gelatin fibers using solutions with low acetic acid concentration: Effect of solvent composition on both diameter of electrospun fibers and cytotoxicity. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 132, 1–11 (2015).

Salles, T. H. C., Lombello, C. B. & D’Ávila, M. A. Electrospinning of gelatin/poly (vinyl pyrrolidone) blends from water/acetic acid solutions. Mater. Res. 18, 509–518 (2015).

Liang, Y., Liang, Y., Zhang, H. & Guo, B. Antibacterial biomaterials for skin wound dressing. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 17, 353–384 (2022).

Ghildiyal, S., Gautam, M. K., Joshi, V. K. & Goel, R. K. Wound healing and antimicrobial activity of two classical formulations of Laghupanchamula in rats. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 6, 241–247 (2015).

Norman, G., Dumville, J. C., Mohapatra, D. P. & Crosbie, E. J. Antibiotics and antiseptics for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, (2015).

Chai, S., Zhou, L., Pei, S., Zhu, Z. & Chen, B. P-doped carbon quantum dots with antibacterial activity. Micromachines 12, (2021).

More, P. R. et al. Silver Nanoparticles: Bactericidal and mechanistic approach against drug resistant pathogens. Microorganisms 11, (2023).

Bruna, T., Maldonado-Bravo, F., Jara, P. & Caro, N. Silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 7202 (2021).

Ji, Y., Liang, K. & Guo, Y. Fabricating polycitrate-based biodegradable elastomer nanofibrous mats via electrospinning. J. Elastomers Plast. 53, 258–269 (2021).

Xiao, Y. et al. Porous composite calcium citrate/polylactic acid materials with high mineralization activity and biodegradability for bone repair tissue engineering. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 70, 507–520 (2021).

Mehraz, L., Nouri, M. & Namazi, H. Electrospun silk fibroin/β-cyclodextrin citrate nanofibers as a novel biomaterial for application in controlled drug release. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 69, 211–221 (2020).

Azimi, B. et al. Bio-based electrospun fibers for wound healing. J. Funct. Biomater. 11, 67 (2020).

Liu, X., Xu, H., Zhang, M. & Yu, D. G. Electrospun medicated nanofibers for wound healing: Review. Membranes (Basel). 11, 770 (2021).

Ding, Z., Dan, N. & Chen, Y. Study of a hydrophilic healing-promoting porcine acellular dermal matrix. Processes 10, 916 (2022).

Nuutila, K. & Eriksson, E. Moist wound healing with commonly available dressings. Adv. Wound Care 10, 685–698 (2021).

Sim, P., Strudwick, X. L., Song, Y. M., Cowin, A. J. & Garg, S. Influence of acidic pH on wound healing in vivo: A novel perspective for wound treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 13655 (2022).

Johnson, D. O. et al. Awareness and use of surgical checklist among theatre users at Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. Niger. J. Surg. 23, 134–137 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Meisam Omidi for his valuable support in this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P.: Performed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the original draft. M.K.: Edited the manuscript, and analyzed the results. S.A.: Conceptualized the study, analyzed the results, wrote the manuscript, and supervised the project. S.O.R.S.: Provided scientific and technical advice.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Partovi, A., Khedrinia, M., Arjmand, S. et al. Electrospun nanofibrous wound dressings with enhanced efficiency through carbon quantum dots and citrate incorporation. Sci Rep 14, 19256 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70295-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70295-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The biomedical potential of polyurethane nanofibrous mats containing nanocellulose-chitosan hybrid nanocomposites for wound dressing applications

Polymer Bulletin (2026)

-

Nanodiamond: a multifaceted exploration of electrospun nanofibers for antibacterial and wound healing applications

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2025)

-

Addressing the silent killer: Nanotechnology for preventing oral bacteria-induced cardiovascular risks

Periodontal and Implant Research (2025)

-

Biopolymers Blend for Microwave-Synthesized Carbon Dots and Iodine Entrapping for Potential Biomedical Bandages

Fibers and Polymers (2025)

-

Nanofiber-Based Biomimetic Platforms for Chronic Wound Healing: Recent Innovations and Future Directions

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (2025)