Abstract

Implicit poisoning in federated learning is a significant threat, with malicious nodes subtly altering gradient parameters each round, making detection difficult. This study investigates this problem, revealing that temporal analysis alone struggles to identify such covert attacks, which can bypass online methods like cosine similarity and clustering. Common detection methods rely on offline analysis, resulting in delayed responses. However, recalculating gradient updates reveals distinct characteristics of malicious clients. Based on this finding, we designed a privacy-preserving detection algorithm using trajectory anomaly detection. Singular values of matrices are used as features, and an improved Isolation Forest algorithm processes these to detect malicious behavior. Experiments on MNIST, FashionMNIST, and CIFAR-10 datasets show our method achieves 94.3% detection accuracy and a false positive rate below 1.2%, indicating its high accuracy and effectiveness in detecting implicit model poisoning attacks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) technology, the number of end devices in people’s lives has surged, greatly enhancing the quality of life. These end devices not only offer more convenient services but also generate a significant amount of data. Effective utilization of this vast amount of information is crucial for optimizing people’s lifestyles. However, due to privacy concerns, people are reluctant to share the personal data collected by these devices. This leads to the problem of data silos, which is widespread in fields like smart IoT and smart healthcare1. Federated Learning, as an emerging distributed learning paradigm, aligns well with the distributed nature of IoT edge devices and plays a significant role in facilitating distributed edge collaboration2. Federated Learning follows the principle of “data stays local, model moves”, allowing users to keep their private data on their own devices, fundamentally ensuring user privacy and maintaining the independence and confidentiality of each participant. This also effectively safeguards data security and privacy, providing a new approach to addressing the problem of data silos in areas like smart IoT. Federated Learning has found widespread application in various privacy-preserving computational scenarios3,4,5.

Although Federated Learning enables lossless training models without direct access to data sources by utilizing local client training and parameter transmission, it faces security challenges, notably poisoning attacks6. These attacks can cause the final model to be inaccurate, deviate from expected values, or even result in significant harm. Attackers deliberately alter training data or inject harmful samples to mislead the model, causing incorrect predictions. In smart healthcare, such vulnerabilities could lead to misdiagnosis, drug misuse, or severe risks to human life, causing immeasurable damage. In IoT devices, successful attacks can lead to financial losses and personal information exposure. Compromised devices might be infected with malicious data, increasing the risk of data leakage through untrusted communication channels7.

Despite various defense strategies against poisoning attacks, such as anomaly detection, Byzantine-resilient aggregation, secure aggregation protocols, and model pruning, these methods are often specific to certain types of poisoning and may have limitations. Their success rate in detecting implicit poisoning attacks is typically low. Implicit attackers covertly poison the model by altering gradient parameters in alternating patterns, making malicious nodes’ trajectories similar to benign ones and harder to detect8,9. Though difficult to notice early on, differences between poisoned and normal parameters can emerge over time10.

This study addresses these gaps by introducing a novel approach that integrates matrix singular value decomposition (SVD) with the Isolation Forest algorithm for anomaly detection in federated learning. Unlike traditional methods that depend solely on changes in model parameters, this approach leverages SVD to extract essential features from model updates, enabling more precise detection of implicit model poisoning attacks and data anomalies. The method significantly improves the detection of implicit attacks by focusing on singular value trajectories, which uncover hidden patterns not identified by conventional techniques. Additionally, enhancements to the Isolation Forest algorithm have been implemented by fine-tuning tree depth and subsample sizes to better handle the heterogeneous and non-IID data characteristics prevalent in federated learning environments.

This paper proposes a poisoning detection method based on singular value trajectory analysis to detect implicit model poisoning in federated learning. By analyzing local client model parameters, it identifies hidden poisoning by examining the singular value trajectories of matrix data. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

A feature extraction method for local model parameters in federated learning client models is proposed.

-

An approach for online detection of poisoning attacks based on time-domain trajectory anomalies during the federated learning process is introduced.

-

A trajectory anomaly detection algorithm based on the Isolation Forest technique is designed, capable of effectively identifying malicious attacks even under implicit attacks by malicious nodes.

The article is structured as follows: The first section introduces the background related to the study; “Related work and problem statement” describes the current state of research on federal learning poisoning detection methods and the process of discovery through the current state; “A novel poison detection method based on trajectory detection” provides a detailed description of the proposed method; “Experiments and performance evaluation” describes the experimental procedure and analyzes its results; finally, the work is summarized and prospected in “Conclusion”.

Related work and problem statement

Model poisoning attack in federated learning

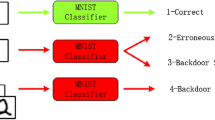

Federated learning poisoning attacks occur when malicious clients manipulate their local data or model updates to degrade federated learning performance or access unauthorized data. These attackers might add malicious data samples or tamper with model updates to cause misleading global model results. Key attack types include data poisoning, model poisoning, backdoor attacks, and malicious servers (Fig. 1). In data poisoning and backdoor attacks, malicious clients use falsified data to manipulate the global model. Malicious servers target the server side, and model poisoning involves providing incorrect updates to the aggregation server, which directly impacts the global model. Due to federated learning’s model-sharing nature, model poisoning is generally more effective than data poisoning11,12.

In federated learning, the aggregation server plays a crucial role in initializing, aggregating, and updating the global model, directly affecting overall model performance. Participants use the global model to overwrite their local models at each iteration’s start, but there’s no validation process for the global model’s correctness. This allows a malicious server to bypass aggregation and distribute a tampered model, introducing backdoors into participants’ local models, posing significant application threats13. However, because this type of attack is conspicuous and server-side security measures are generally robust, this paper focuses on other attack vectors within federated learning. Data poisoning attacks were first introduced by Biggio et al.8, where attackers manipulate training data (e.g., by adding fake data) to mislead the model into learning incorrect mapping relationships, reducing accuracy. In federated learning, attackers can implement data poisoning by controlling participants or tampering with their training datasets. Aggregation algorithms can help mitigate data poisoning’s impact on the global model14. Model poisoning attacks involve tampering with model weight parameters or gradient information to compromise the model. In federated learning, each participant sends local model updates to a central server. Since local data and training processes are invisible to the server, it cannot verify the authenticity of these updates, allowing attackers to send malicious updates and influence the global model. Algorithms like FedProx aggregate model updates using linear combinations15, but malicious participants can still disrupt the global model by manipulating updates16. Mhamdi et al. noted that in high-dimensional gradient spaces17, lp-norm-based aggregation algorithms (e.g., Krum) might not effectively distinguish between small accumulations across multiple dimensions and significant deviations in one dimension. Attackers can exploit this by introducing bias in a single dimension and conspiring with multiple malicious participants to degrade global model accuracy.

Researchers have explored various model poisoning strategies. Fang et al. proposed a non-directional attack strategy18 involving adding a perturbation vector \(\lambda _{\mathrm {~S}}\) to the previously aggregated global model, creating maximum deviation from the typical update path and compromising global model performance. Bhagoji et al. designed a stealthy directional attack by adding a small gradient offset to the previous global gradient8, aiming to minimize the global model’s cross-entropy loss. They incorporated local training loss for malicious participants and the l2 distance from the average gradient of the previous global model to ensure stealthiness. These studies collectively indicate that model poisoning attacks represent a significant threat in federated learning, highlighting the importance of robust anomaly detection algorithms to counter such attacks.

Model poisoning detection method

Research on defenses against model poisoning attacks in federated learning generally falls into three categories: Byzantine aggregation, leveraging model characteristic differences, and secure hardware.

Given the variety of existing poisoning attacks, many detection and defense studies have emerged19,20,21. Damaskinos et al. proposed “Aggregathor” to achieve Byzantine fault tolerance in machine learning through robust gradient aggregation22. This method uses a sorting-based strategy to mitigate the influence of malicious nodes, ensuring the accuracy and robustness of the global model. References23,24,25 rely on lp distance between gradients to measure differences, assuming malicious gradients deviate significantly from the mean of normal gradients. Based on this, they propose aggregation algorithms using gradient averages or medians. Blanchard et al.23 introduced Krum and Multi-Krum algorithms. Krum selects a gradient closest in L2-norm space to its \(n-m-2\) neighboring gradients. Multi-Krum sequentially selects c participants using Krum and averages their gradients, ensuring \(n-c>2m+2\). Xie et al.25 and Yin et al.24 showed that taking the median of each gradient dimension improves security by reducing the impact of outliers and malicious updates. A direct defense strategy is detecting malicious clients. Attackers submit malicious updates that differ from normal ones. The aggregation server can analyze all collected updates to detect possible attacks. Papers2627 use cosine similarity to describe the difference between normal and malicious updates. Muñoz-González et al.26 calculate a weighted average of all updates in each iteration and use cosine similarity to differentiate between malicious and normal participants. Khazbak et al.27 calculate similarity scores based on cosine similarity between a participant’s update and others’, selecting the top \(n-m\) participants for aggregation, assuming most participants are benign (\(n > 2m\)). Researchers have also proposed using secure hardware to ensure the integrity of local training, preventing attackers from uploading malicious updates. Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs), such as Intel’s SGX28, provide hardware-level security by storing sensitive data and code within a secure enclave. Chen et al. loaded participants’ local model training and server aggregation into SGX enclaves, preventing malicious servers from issuing poisoned models directly29. However, SGX supports only CPUs, limiting its utility for GPU-accelerated deep learning models. Its limited Protected Range Memory (PRM) may also reduce local training efficiency due to frequent page swapping.

Implicit poisoning attackers use stealthier techniques by alternating gradient parameters, making malicious updates’ trajectories less distinguishable from normal ones. Traditional clustering algorithms target offline datasets, while client updates in federated learning are continuous data streams. To address this, our method analyzes client parameter trajectories over time and uses the Isolation Forest anomaly detection algorithm to detect dynamic trends and potential poisoning attacks. This approach effectively detects malicious clients in federated learning models with a high proportion of malicious participants.

Mode detection method for trajectory anomalies

Traditional time-series anomaly detection typically focuses on identifying anomalies within a single time sequence, which may not effectively address the unusual gradient matrix trajectories uploaded by malicious clients in federated learning. Existing trajectory anomaly detection methods are often designed for offline learning, requiring all data to be available upfront and allowing model parameters to be adjusted. Online trajectory anomaly detection, on the other hand, is more flexible, enabling the model parameters to be updated on the fly, supporting real-time detection.

Early distance-based methods, like Knorr et al.’s algorithm, could detect outlier points but were inefficient when handling large-scale trajectory data30. Zhang et al. developed the iBAT algorithm31, which used Isolation Forest to identify anomalous patterns in GPS trajectories, but it had limitations with dynamic data. Chen et al.’s iBOAT algorithm improved upon iBAT by using an adaptive window strategy for online anomaly detection in trajectories32.

Deep learning methods have made breakthroughs in online dynamic trajectory detection, such as Liu et al.’s deep generative sequence model33. However, these methods may require more computational resources and depend heavily on the quality and diversity of training data. This paper proposes a time-domain-based detection method that tracks changes in the singular values of client model updates to detect anomalous trajectories. This approach, while maintaining real-time capabilities, can accurately detect abnormal trajectories in federated learning. By monitoring the trends in client model changes, it can quickly identify potential malicious behavior, providing an efficient solution for online anomaly detection. This method aims to strike a balance between real-time performance and accurate detection, making it suitable for federated learning environments where data is continuously updated, and robust anomaly detection is essential.

Problem statement

Existing research on model poisoning has revealed strategies with a high degree of stealth, making defense and detection increasingly challenging due to the cleverness and destructiveness of these tactics. For malicious nodes, an attack strategy that alternates gradient update variables in each round can be particularly covert. This technique ensures that the update trajectories of malicious nodes do not significantly deviate from those of normal nodes, enhancing stealth and complicating detection and identification. While these stealthy attacks might be difficult to detect in the early stages in Fig. 2a, with continued model updates, subtle differences may emerge between the toxic parameters uploaded by malicious nodes and the normal model parameters, even if these differences are minimal. This creates a narrow window for detecting anomalous patterns, requiring advanced techniques to distinguish between legitimate and malicious model updates in federated learning environments.

Comparison of singular value trajectories and difference trajectories for client parameters. (a) The singular value trajectories of malicious and normal client parameters are nearly identical, making them difficult to distinguish. (b) Singular Value Difference Trajectory Plot, difference trajectory effectively highlights the differences between the two types of clients compare to (a).

Although malicious nodes maintain the same overall trend as normal nodes when injecting poison during updates, their changes from one update to the next tend to be more significant. To expose this variance, we can reconstruct the trajectory using gradient updates, where each point on the trajectory represents the difference between the current update and the previous one. By calculating these differences, we obtain a series of vectors that describe the update offset introduced by malicious nodes, allowing us to create a line plot of the difference vectors. This approach helps to reveal implicit attacks introduced by malicious nodes in each update, aiding in identifying possible poisoning behavior. By comparing the trajectories of malicious nodes with those of normal nodes, we can detect anomalies and visually represent the results in a line plot in Fig. 2b. This method provides a clear way to differentiate between normal and malicious patterns of behavior in federated learning, allowing for the detection and identification of poisoning attacks.

As shown in Fig. 2b, although the time-series trajectories of malicious nodes generally align with those of normal nodes, their difference trajectories exhibit significant disparities. These variations can be used to detect malicious nodes’ attack behavior. Therefore, we propose an anomaly detection method based on difference trajectories, which combines traditional anomaly trajectory detection models to identify toxic attacks by malicious nodes. This method involves computing the difference between successive updates to generate a trajectory that represents the incremental changes. By comparing the difference trajectories of normal and malicious nodes, we can detect abnormal patterns that may indicate a poisoning attack. The significant differences in these trajectories provide a reliable means of identifying malicious behavior in federated learning.

A novel poison detection method based on trajectory detection

In this approach, the aggregation server in federated learning computes and stores the singular values of local model parameters for each epoch round. After more than one round of iterations, the difference between the singular values of this round and the previous round is calculated. The resulting values are then fed into the IForest algorithm for outlier detection. Subsequently, the trajectory of updates from each node is used to determine if a particular client has been poisoned.

Method detects anomalies by examining the differences in singular values between consecutive iterations. Using an improved Isolation Forest algorithm, we analyze these differences across clients to filter out anomalies. In this context, normal client values cluster together, while anomalous ones deviate from the norm. The Isolation Forest algorithm effectively separates data points by constructing random trees, isolating anomalies more easily than normal points. With a time complexity of \(O(n \log n)\), it handles large-scale data well and supports unsupervised learning, enabling detection without labeled data.

Parameter Collection: Gather parameter update matrices \(W_i\) from all clients.

SVD: Apply SVD on each \(W_i\) to obtain singular values \(\Sigma _i\).

Analysis: Calculate changes in singular values for each client and identify significant deviations.

Detection: Use the Isolation Forest algorithm to detect anomalies and identify malicious clients.

The overall design is shown in Fig. 3.

The overall algorithm is shown in table.

In this scheme, after the trajectory length is greater than or equal to L, the client honesty O is calculated, which is implemented by the function computerHonesty. If O is greater than or equal to the honesty threshold \(\rho\), the weight of this client will be 0 , computerHonesty is implemented as follows:

After traversing the local model parameters of all the clients, since it is possible that multiplication reduces or addition increases the weights of some clients, but to keep the sum of all client weights equal to 1; therefore, it is necessary to redistribute the weights and distribute the adjusted reduced weights equally to all normal clients. The function ResignWeight does this job and is implemented as shown in Eq. (1). The outputs of the algorithm are the local model parameters adjusted by the weights. The form and structure remain unchanged and can be used directly by FedAvg. Such an approach implements the hot plugging of the present algorithm, which can be easily implanted into existing Federated learning systems.

Poisoning method hypothesis

Bhagoji’s goal is to ensure that the classifier learned on the server performs targeted misclassification of the auxiliary data. The auxiliary data consists of samples \(\{X_i\}_{i=1}^r\) and true labels \(\{Y_i\}_{i=1}^r\), which shall be categorized as the desired target class \(\{\tau _{i}\}_{i=1}^{r}\). The antagonistic targets are

The literature13 aims to make the global model misclassify a specific set of samples when tested, making it possible to misclassify individual samples, and proposes alternating minimization-based model poisoning attacks to make poisoning updates appear similar to benign updates, such that the attacks are more insidious and difficult to detect. According to the attack method proposed in the literature13, this paper makes the following assumptions on the poisoning party.

The malicious nodes are non-colluding, meaning their updates have limited impact on the global model. The data are distributed among clients in an I.I.D. manner, making it easier to distinguish benign and malicious updates, but more difficult to achieve attack stealth. Malicious clients have access to a subset of training data \(\mathscr {D}_{m}\) and auxiliary data drawn from the same distribution as training and test data, which are part of their adversarial target. After each iteration, parameters uploaded by malicious clients show no noticeable difference compared to benign clients.

Matrix feature extraction and trajectory recognition

The IForest algorithm has shown better robustness and performance results among other machine learning algorithms when considering the overall performance of the algorithm. Therefore, we use the IForest algorithm to detect anomalies in the approach of this paper.

The Isolated Forest framework is shown in Fig. 4.

Isolated Forest Framework, by randomly selecting samples and features, a binary tree consisting of isolated and normal points is constructed, and multiple trees are repeated to form a forest. The degree of abnormality of a sample is evaluated based on the length of its path in the tree; the shorter the path, the more likely the sample is an abnormal point.

To determine the parameters for the Isolation Forest, we use grid search to find the optimal hyperparameter combination for the model.

First, we define the grid search space by selecting ranges for the number of trees, sample size, and maximum tree depth parameters, and then subdivide within these ranges. We implement grid search and evaluate the model’s performance by testing it on a test set to ensure accuracy and robustness in anomaly detection. Through these steps, we determined that the optimal parameters for the Isolation Forest model are 100 trees, a sample size of 256, and a maximum tree depth of 10, which enhances the effectiveness of anomaly detection.

In our research, we applied trajectory data to the Isolation Forest algorithm to detect anomalous trajectories. Through grid search experiments, we set the following parameters:

Number of Trees: We used 100 trees in the experiments to ensure sufficient diversity during the detection process.

Sample Size: The sample size for each tree was set to 256, which is the default setting as it provides a good balance.

Maximum Tree Depth: We set the maximum tree depth to 10, which has proven effective in practice, ensuring rapid isolation of data points.

Randomness: We introduced a degree of randomness in tree construction to enhance the ability to detect anomalies.

Feature Selection: During the use of the Isolation Forest algorithm, we performed feature selection on the trajectory data to ensure that the selected features were relevant to anomaly detection.

For the aggregation server, the model sent by each remote client after a certain iteration is a number of matrices, including a parameter matrix for each layer. One of the output layers transmits the final model trained locally (this iteration). The locally trained local model matrix is chosen as the representative matrix, and this matrix is operated on for singular values. However, the calculation of the singular value of the matrix can only be performed if the matrix is a square matrix of \(m\times m\). In this method, the matrix is transposed with itself to obtain a matrix that still has the properties of a parametric model, and this matrix is calculated to find the singular value of the matrix in the following way.

where \(M_{it}\) is the parameter matrix uploaded by client i for the ith time, \(\textrm{T}_{-}\textrm{it}T_{it}\) is the \(\text {i-th}\) singular value of the client, N is the number of clients in federated learning, and E is the number of times the federated learning clients are trained locally. The clients upload the local model parameters after each iteration, the aggregation server performs the extraction of the singular values of the matrix and saves them, records the singular values in chronological order, calculates the difference between the singular values of the local model parameters after the latter iteration and the singular values of the previous one, and then uses IForest to perform outlier detection on the results of all clients in the following way:

where, \(C_{ij+1}\) is the jth feature value of client i in the server-side trajectory; \(\mathbf {R_{ij}}\) is the outlier detection junction, for the outlier, the output is 1, otherwise the output is 0. After n iterations, the trajectory of each client’s parameter processing result is obtained, and the attack behavior of malicious nodes is identified according to the trajectory features. The trajectory of the client can be expressed as

Hyperparameter definitions

Since all anomaly detection algorithms have the possibility of false positives, it is not possible to conclude that a client is a malicious node based on a single identification result. Multiple consecutive judgments are required. Using the trajectories in the completed iteration would lead to accurate results considering the adequate evidences, but the attack behavior has already affected the global model. Therefore, a dynamic adjustment machine is designed in this scheme to reduce the impact of the attack behavior on the global model before concluding the malicious node. Define hyperparameters: weight \(\omega _{i}\) of client i and \(\sum _{i}\omega _{i}=1\); initial length L of the trajectory, honesty threshold \(\rho\), and penalty factor \(\alpha\). On the server side, a weight is assigned to each client for setting the weight of the role of the local model parameters provided by each client in the aggregation process, and the initial value of \(\omega _{i}\) is 1/N. According to the algorithm, the second iteration starts and the first outlier detection result \(R_{i1}\) of each client is obtained, and the penalty factor is used to adjust the weight of the local model parameters of client i in the next round in the global update according to \(R_{i1}\). The weighting update method is as follows:

Where, m is the number of clients with all weights not less than 1/N in this iteration. Such an update strategy decreases the weight multiplication when the client is suspected of attack, and increases the weight wig if it behaves normally in the subsequent iterations. The initial length L of the trajectory determines the confirmation of malicious clients after several iterations. the larger L is, the more accurate the judgment result is, but too large L will lead to a larger impact on the global model; when L takes a small value, it can instantly mitigate the impact of the attack on the global model, but there may be wrong judgment; and, the value of L is related to the honesty threshold \(\rho\).

Experiments and performance evaluation

We conducted experimental evaluations within the federated learning framework FedAvg to assess the effectiveness of our method in detecting covert model poisoning attacks. Initially, experiments were conducted using a small-scale federated learning system with 10 clients. Subsequently, we evaluated the efficiency and performance of the algorithm in a larger-scale system with 50 clients.

Experimental setup

The central server’s configuration is OS: Ubuntu 18.04.5, CPU: 12 vCPU Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 8255C CPU @ 2.50GHz, Memory: 40GB, GPU: RTX 3080(24GB) \(\times\) 1. The attack scenario follows the method from literature13. Initially, we used only the MNIST dataset, setting the client size to 10 and increasing the number of malicious nodes from 1 to 4, training the clients for 50 iterations. Model parameters for each iteration were recorded, processed, and saved according to our procedure.

We observed the results and preliminarily determined the hyperparameters. Subsequently, experiments were conducted on larger-scale systems (20, 30, 40, 50 clients) to compare model testing across multiple datasets, including MNIST, FashionMNIST, and CIFAR-10. These datasets were used to train federated learning models and simulate distributed data in an IoT environment, ensuring representative data distribution to mimic real-world scenarios.

We employed the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm to coordinate model updates among clients. Each client independently trains its model and then sends the updated weights to the server for aggregation. In federated learning, secure aggregation algorithms are crucial for defending against model attacks. The FedAvg algorithm is simple yet practical, averaging parameters uploaded by users with weights determined by the number of samples they own. While FedAvg partially protects privacy, the demands on aggregation algorithms are increasing with the advancement of federated learning. The experiment included 50 training epochs to ensure model convergence.

For model attacks, our defense focuses on detecting incorrect model parameters. One approach is to use the difference in parameter values directly for detection. Each client provides n parameters, and if one client’s parameters significantly differ from others, they are judged as abnormal. Another method involves the server processing the parameters \(W_{i}^{n}\) loaded by a client, calculating them with parameters uploaded by other clients, and comparing \(WG_{i}\). If it exceeds a certain set value, the model parameters are considered abnormal.

The security aggregation algorithm is also a common and effective defense method in federated learning settings. It plays a key role in any centralized topology and horizontal federation learning environment, defending against model attacks. The FedAvg aggregation algorithm, simple and practical, averages parameters uploaded by users with different weights, determined by the number of samples each user has. Although FedAvg can protect privacy to some extent, the demands on aggregation algorithms are increasing with the development of federated learning.

Performance indicators

The method in this paper evaluates detection success qualitatively and quantitatively by adjusting the number of poisoning nodes and iterations. Poisoning data and models significantly degrade machine learning model predictions. To assess poisoning detection algorithms, a more intuitive approach involves training models on cleaned datasets and comparing detection accuracy on test sets. Malicious behavior is identified by detecting client training behavior and model weight contributions, analyzed using statistical methods. If abnormal behavior is detected for a client in each iteration, it is flagged as suspected malicious, with its aggregation weight reduced based on anomaly score. Clients with abnormal behavior exceeding half are classified as malicious and removed from training.

In this paper, the poisoning nodes are self-set. Therefore, to assess the success rate, we only need to consider whether the detection results for poisoning are correct and whether the clients detected as poisoning are the ones set as poisoning nodes. To accurately evaluate the experimental results, we have introduced various evaluation metrics:

Detection Accuracy (DACC): This metric represents the overall learning accuracy and is used to gauge the overall performance of different defense methods against poisoning attacks in federated learning. It reflects the average learning accuracy of the system.

Misclassification Rate: This refers to the proportion of samples that are misclassified based on predefined decision rules during analysis. In the context of this paper, it indicates the percentage of normal clients mistakenly identified as poisoned clients out of the total sample size.

These metrics provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating the effectiveness of the proposed method in detecting poisoned clients and assessing the robustness of federated learning systems against various attack scenarios.

Experimental process

The poisoning method in reference8 is used and alternating poisoning modifications on their poisoning attacks to make their poisoning more covert. In the process of federal learning, the local model parameters of each iteration of the local client are recorded, and the singular values are calculated for each iteration of the parameters, and a trajectory can be formed when it is iterated more than three times, and a conventional model poisoning detection algorithm is used to detect whether the trajectory of the client is outlier to determine whether this client is poisoned. Record the local model parameters after each iteration and extract the singular values of the matrix for the local parameters, record the singular values in chronological order, and judge the trend of the trajectory formed by the singular values of the local model parameters after the latter iteration in conjunction with the singular values of the previous one.

The method involves recording singular values of client parameters chronologically. After each iteration, applying a conventional poisoning detection algorithm to detect significant outlier trajectories in parameter singular values. Simultaneously, calculating the difference between posterior and anterior iterations to obtain a delta value representing the trend of change. Applying the IForest algorithm to detect anomalies in delta values, identifying suspected anomaly points. Filtering these points based on differences between poisoning and normal clients’ parameters. Examining each suspected anomaly point to exclude falsely classified normal points. Recording identified anomalies and dynamically accumulating anomaly counts for each client. Marking a client as suspicious if anomalies persist for more than 2 consecutive times, reducing its weight in the federated learning model. After 3 iterations, if anomalies continue, the client is deemed as poisoned and removed.

We conducted studies on different numbers of clients with poisoning rates of 10% under the MNIST, FasshionMNIST, and CIFAR-10 datasets. The comparative results are shown in Fig. 5, the figure shows that the number of clients has little impact on the filtering accuracy of our method, indicating its effectiveness in screening out malicious clients.

We conducted studies on 50 clients separately under the MNIST, FashionMNIST, and CIFAR-10 datasets with varying poisoning rates in Fig. 6, the figure indicates that the proportion of malicious clients in the client pool has a significant impact on the filtering accuracy of our method. The lower the proportion of malicious clients involved in poisoning, the higher the filtering accuracy. Additionally, the figure also shows that our method achieves better filtering accuracy on the MNIST dataset compared to the other two datasets.

In poisoning attacks, the proportions of malicious clients are set to 0.1, 0.28, and 0.4, respectively. The dataset is evenly distributed among 10 users (later increased to 50 for realism). To compensate for the low substitution rate, the training process is lengthened. Federated learning occurs over 50 global epochs, with all clients initially participating. Poisoning clients are determined after 5 local training epochs start. In the MNIST dataset, the proportion of poisoning clients is set to 0.1, and verification accuracy after 5 epochs is 94.3%. Real-time client detection is conducted throughout the federated learning process until the epochs are complete.

Experimental analysis

Model poisoning attacks are an important threat to federal learning, and the best solution to defend against poisoning attacks is still under discussion. In this paper, we propose a poisoning attack detection method based on trajectory anomaly identification matrix singular values. Through comparative experiments, we find that the method proposed in this paper can effectively defend against poisoning attacks and outperforms VAE34 and FLDetector35 in most cases. To evaluate the method in this paper, the datasets to be detected by the poisoning methods mentioned above that produce data with different percentages of poisoning are compared and analyzed with the method used in this paper. The performance of the algorithms is compared according to the following different metrics. As shown in Table 1.

Table 1 presents a comparison of our method with other approaches, with evaluation metrics including Detection Accuracy (DACC) and False Positive Rate (FPR). DACC represents the proportion of correctly identified poisoned clients, while FPR indicates the proportion of poisoned clients wrongly classified as benign clients.

From the table, it is evident that our method outperforms the other two approaches in terms of both filtering accuracy and false positive rate on the MNIST and FashionMNIST datasets. However, on the CIFAR-10 dataset, our method ranks second to the other two approaches.

Performance and scalability

This anomaly detection method is applicable across a range of domains including smart homes, smart cities, healthcare, and industrial automation. By identifying malicious behaviors, it ensures the security and stability of federated learning systems. To protect client data privacy, our anomaly detection mechanism avoids direct access to the original data by analyzing features of model updates. Specifically, key features of model updates are extracted using matrix SVD and combined with the Isolation Forest algorithm for anomaly detection, thereby preventing direct exposure of client data. Our method performs effectively in large-scale and diverse federated learning environments, accommodating data with various features and enhancing system security in a range of IoT scenarios.

Algorithm Performance: Client numbers minimally affected detection results, highlighting algorithmic robustness across scales. This stability stems from balanced client data contributions to global model training, essential for real-world mobile federated learning scenarios.

Scalability: Our method effectively detects up to 40% of malicious nodes, showcasing its robustness against interference. It can adapt to varying proportions of malicious nodes while maintaining federated learning effectiveness. However, we acknowledge that in extreme cases, such as when half of the nodes are malicious, existing methods may face challenges. For poisoning attacks executed by a large number of colluding clients, the current anomaly detection mechanism may struggle with identification. Consequently, additional defense strategies may be required to enhance federated learning security. This will be the focus of our future research.

Conclusion

The paper proposes a poisoning attack detection method based on matrix singular values for identifying trajectory anomalies, effectively detecting implicit poisoning points in federated learning training on FashionMNIST and MNIST datasets. Experimental results demonstrate high accuracy even when poisoning points reach 40%. The algorithm focuses on fitting multiple parameter iterations of clients to identify trajectory anomalies. This versatile method can be extended to various applications in smart healthcare, smart cities, and IoT technology, ensuring data security, privacy protection, and defense against potential poisoning attacks.

Data availability

Accession codes: The datasets (MNIST, FashionMNIST, and CIFAR-10) used during the current study are publicly available and can be accessed via their respective repositories: MNIST (http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/), FashionMNIST (https://github.com/zalandoresearch/fashion-mnist), CIFAR-10 (https://www.cs.toronto.edu/kriz/cifar.html). Any other data used during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, Y., Qin, X., Wang, J., Yu, C. & Gao, W. Fedhealth: A federated transfer learning framework for wearable healthcare. IEEE Intell. Syst. 35, 83–93 (2020).

Nguyen, D. C. et al. Federated learning for internet of things: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surveys Tutorials 23, 1622–1658 (2021).

Yang, Q., Liu, Y., Chen, T. & Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 10, 1–19 (2019).

Li, Y., Li, J. & Wang, Y. Privacy-preserving spatiotemporal scenario generation of renewable energies: A federated deep generative learning approach. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 18, 2310–2320 (2021).

Li, Y., He, S., Li, Y., Shi, Y. & Zeng, Z. Federated multiagent deep reinforcement learning approach via physics-informed reward for multimicrogrid energy management. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. (2023).

Gosselin, R., Vieu, L., Loukil, F. & Benoit, A. Privacy and security in federated learning: A survey. Appl. Sci. 12, 9901 (2022).

Al-Qerem, A., Alauthman, M., Almomani, A. & Gupta, B. B. Iot transaction processing through cooperative concurrency control on fog-cloud computing environment. Soft. Comput. 24, 5695–5711 (2020).

Bhagoji, A. N., Chakraborty, S., Mittal, P. & Calo, S. Analyzing federated learning through an adversarial lens. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 634–643 (PMLR, 2019).

Yang, J. et al. Clean-label poisoning attacks on federated learning for iot. Expert. Syst. 40, e13161 (2023).

Zhang, J., Wu, D., Liu, C. & Chen, B. Defending poisoning attacks in federated learning via adversarial training method. In Frontiers in Cyber Security: Third International Conference, FCS 2020, Tianjin, China, November 15–17, 2020, Proceedings 3, pp. 83–94 (Springer, 2020).

Bagdasaryan, E., Veit, A., Hua, Y., Estrin, D. & Shmatikov, V. How to backdoor federated learning. In International conference on artificial intelligence and statistics, pp. 2938–2948 (PMLR, 2020).

Qu, Z. et al. Localization of dummy data injection attacks in power systems considering incomplete topological information: A spatio-temporal graph wavelet convolutional neural network approach. Appl. Energy 360, 122736 (2024).

Rathee, M., Shen, C., Wagh, S. & Popa, R. A. Elsa: Secure aggregation for federated learning with malicious actors. In 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), pp. 1961–1979 (IEEE, 2023).

Moshawrab, M., Adda, M., Bouzouane, A., Ibrahim, H. & Raad, A. Reviewing federated learning aggregation algorithms; strategies, contributions, limitations and future perspectives. Electronics 12, 2287 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 2, 429–450 (2020).

Blanchard, P., El Mhamdi, E. M., Guerraoui, R. & Stainer, J. Machine learning with adversaries: Byzantine tolerant gradient descent. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Mhamdi, E. M. E., Guerraoui, R. & Rouault, S. The hidden vulnerability of distributed learning in byzantium. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.07927 (2018).

Fang, M., Cao, X., Jia, J. & Gong, N. Local model poisoning attacks to \(\{\)Byzantine-Robust\(\}\) federated learning. In 29th USENIX security symposium (USENIX Security 20), pp. 1605–1622 (2020).

Tiwari, P., Lakhan, A., Jhaveri, R. H. & Grønli, T.-M. Consumer-centric internet of medical things for cyborg applications based on federated reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 69, 756–764 (2023).

Li, Y., Wei, X., Li, Y., Dong, Z. & Shahidehpour, M. Detection of false data injection attacks in smart grid: A secure federated deep learning approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 13, 4862–4872 (2022).

Qu, Z. et al. Active and passive hybrid detection method for power cps false data injection attacks with improved akf and gru-cnn. IET Renew. Power Gener. 16, 1490–1508 (2022).

Damaskinos, G., El-Mhamdi, E.-M., Guerraoui, R., Guirguis, A. & Rouault, S. Aggregathor: Byzantine machine learning via robust gradient aggregation. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 1, 81–106 (2019).

Blanchard, P., El Mhamdi, E. M., Guerraoui, R. & Stainer, J. Machine learning with adversaries: Byzantine tolerant gradient descent. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Yin, D., Chen, Y., Kannan, R. & Bartlett, P. Byzantine-robust distributed learning: Towards optimal statistical rates. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 5650–5659 (Pmlr, 2018).

Xie, C., Koyejo, O. & Gupta, I. Generalized byzantine-tolerant sgd. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.10116 (2018).

Muñoz-González, L., Co, K. T. & Lupu, E. C. Byzantine-robust federated machine learning through adaptive model averaging. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.05125 (2019).

Khazbak, Y., Tan, T. & Cao, G. Mlguard: Mitigating poisoning attacks in privacy preserving distributed collaborative learning. In 2020 29th international conference on computer communications and networks (ICCCN), pp. 1–9 (IEEE, 2020).

McKeen, F. et al. Innovative instructions and software model for isolated execution. Hasp@ isca 10 (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. A training-integrity privacy-preserving federated learning scheme with trusted execution environment. Inf. Sci. 522, 69–79 (2020).

Knorr, E. M., Ng, R. T. & Tucakov, V. Distance-based outliers: Algorithms and applications. VLDB J. 8, 237–253 (2000).

Zhang, D. et al. ibat: detecting anomalous taxi trajectories from gps traces. In Proceedings of the 13th international conference on Ubiquitous computing, pp. 99–108 (2011).

Chen, C. et al. iboat: Isolation-based online anomalous trajectory detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 14, 806–818 (2013).

Liu, Y., Zhao, K., Cong, G. & Bao, Z. Online anomalous trajectory detection with deep generative sequence modeling. In 2020 IEEE 36th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), pp. 949–960 (IEEE, 2020).

Li, S., Cheng, Y., Wang, W., Liu, Y. & Chen, T. Learning to detect malicious clients for robust federated learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.00211 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Cao, X., Jia, J. & Gong, N. Z. Fldetector: Defending federated learning against model poisoning attacks via detecting malicious clients. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pp. 2545–2555 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhiying Ding and Xu li designed the attack dectiontin scheme. Jindong Zhao and Wenshuo Wang designed framework of whole system and did the attack detecting experiments. Gwanggil Jeon and Xuan Wang completed the attack experiments. The solution was inspired by Chunxiao Mu. Xuan Wang performed the review of cybersecurity issues that are now presented in the paper and helped write the new version of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, Z., Wang, W., Li, X. et al. Identifying alternately poisoning attacks in federated learning online using trajectory anomaly detection method. Sci Rep 14, 20269 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70375-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70375-w