Abstract

The relationship between solar magnetic activity and solar wind parameters, with observed time-delayed mutual coupling, is an outstanding challenge in space physics. In this study, drawing inspiration from recent observations, we propose a reconciliation framework whose fundamentals stand in the Parker model for solar wind expansion. We investigate the effects on fluctuations in solar wind speed when linearly sustained by an oscillating magnetic solar dynamo described via a modified Van der Pol nonlinear oscillator mimicking the magnetic activity at different timescales. Our findings reveal the presence of a “space-climatic feedback” that, in absence of the driving magnetic activity, slows down solar wind velocity fluctuations. The combined action of the slowing down of fluctuations and a periodic driving is the responsible for the time-delay between solar magnetic activity and solar wind dynamics. Furthermore, we also demonstrate how the space-climatic feedback controls the value of the time-delay which depends on the different periodicities of the driving magnetic activity. This holistic approach provides a formal link at the interplay between solar magnetic activity and solar wind dynamics through the interplanetary space which can advance our understanding of long-term effects of solar activity on solar wind variations, and consequently on interactions with planetary environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The magnetic activity of the Sun, mainly driven by the core \(\alpha -\omega\) dynamo, affects the interplanetary space through fluctuations in solar wind plasma parameters. Such variations cover a wide range of temporal and spatial scales, spanning from seconds up to years, and are detected throughout the Heliosphere and beyond 1,2,3,4. Within this spectrum of scales, two dominant timescales are usually identified and used to distinguish between Space Weather and Space Climate phenomena 5: the solar rotation period (approximately 27 days) and the Schwabe’s cycle, also known as the 11-year solar cycle. Space Weather and Space Climate both pertain to phenomena occurring in the near-Earth environment, but they differ in their temporal scales and their effects on Earth. Space Weather usually refers to the short-term variations in the space environment caused by the Sun’s activity and its interactions with Earth’s magnetic field and atmosphere6. It includes solar phenomena such as solar flares, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), interplanetary variations in the solar wind conditions, and near-Earth ones as geomagnetic storms and ionospheric disturbances6. Space Climate, on the other hand, deals with the long-term average behavior and variations in the space environment 1,2. It encompasses trends and patterns in solar magnetic activity, the long-term effects on the Earth’s magnetic field, and other space-related parameters over longer timescales, ranging from years to centuries. Space Climate variations can result from changes in solar activity, solar wind parameters, solar irradiance variability, also due to variations in Earth’s orbit and rotation, often involving studying historical data and paleoclimate records2,3,7.

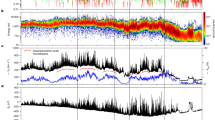

When focusing on Space Climate phenomena, the main periodicities related to solar activity (as quasi-biennial oscillations, i.e., QBOs, and the Schwabe solar cycle) have been clearly identified in several solar magnetic-related variables (e.g., SunSpot Number (SSN), SunSpot area, F10.7cm, and chromospheric proxies8,9,10,11), as well as, solar wind and Earth-based observations (e.g., plasma parameters, geomagnetic, ionospheric, and thermospheric indices12,13,14,15,16,17). This fostered ongoing discussions regarding the possible phase-amplitude modulations and relationships between solar activity proxies and near-Earth solar wind parameters on the ecliptic plane18,19,20,21,22. By using both linear cross-correlation analysis and recently introduced Information Theory-based metrics (as the Transfer Entropy) it has been shown that there is a net information flow from solar activity indices, like the Ca II K index, to solar wind parameters, as dynamic pressure and wind speed, aligning with previously observed time lags of approximately 3 years22,23,24. Notably, these time-delays exhibit variability across solar cycles, with solar wind parameters showing longer delays in response to solar activity in cycles 20 and 21, while subsequent cycles (22, 23, and 24) exhibit shorter time lags21,23. These evidences likely suggest the existence of some large-scale “climatic” feedbacks driven by magnetic solar activity variations and leading to fluctuations in solar wind parameters, as already theoretically reported using a dynamo-wind coupled model25. However, it is important to remark that previous studies focused on monthly and yearly averaged solar wind speed at the ecliptic plane, whose source variations over the 11-year solar cycle26 may likely represent the physical origin of the observed time shift. Indeed, during solar minimum the ecliptic plane is dominated by slow solar wind from Helmet streamers. In contrast, during solar maximum and declining phase, the ecliptic solar wind is a mix of fast Alfvénic wind from Coronal Holes, High Speed Streams from Corotating Interaction Regions and slow wind from streamers27,28.

Inspired by the latter considerations, here we propose how to reconcile the observation of the existence of a time-delay between solar magnetic activity and solar wind parameters. We build a simple linear model for large-scale velocity fluctuations of the Parker model, driven by a self-sustained magnetic solar dynamo, described by a nonlinear Van der Pol equation. The combined action of the slow down of fluctuations by a space-climatic feedback and their periodic driving, is responsible for the observed time-delay. Using the Parker model for the unperturbed solar wind speed, we find that the space-climatic feedback depends on the various frequencies (periodicities) of the driving mechanism of fluctuations.

The model

We begin our model formulation starting from the evidence of an average \(\sim\) 3.2-year time-delay observed over the last 5 solar cycles between a physical proxy of the solar magnetic activity, namely the Ca II K 0.1-nm emission index (hereafter simply referred to as Ca II K index)29, and a solar wind parameter, namely the wind speed (Fig. 1).

To account for a link between solar wind radial velocity and solar magnetic activity, we use the well-known Parker model which describes the large-scale (temporal) radial profile of the solar wind velocity field under stationary conditions 30,31. Indeed, by assuming the solar wind as a collisionless plasma, by neglecting magnetic field effects on strain and pressure terms, and by assuming spherical geometry, the solar wind radial velocity profile v(r) is described by

where \(r_c = G M_\odot /2c_s^2 \simeq 7 \times 10^6\) km is the critical point for a supersonic expansion (about 10 solar radii), and \(c_s = (RT)^{1/2} \simeq 10^2\) km/s is the coronal sound speed. The solution (1), under small perturbations, can be linearized and it is expected that fluctuations can grow around the stationary (stable) equilibrium solution derived by Parker 30 due to solar wind expansion32. In the simplest approximation, if we assume purely radial fluctuations whose amplitudes only depend on r and t (this is valid under spherical geometry), the dynamics of velocity field fluctuations \(\delta v\) can be described by the linearized equation of motion for a hydromagnetic gas31

where \(B_0\) is the background magnetic field, \(\rho _0\) the constant mass density and \(\delta \textbf{B} = \mathbf {\nabla } \times \delta \textbf{A}\) the fluctuating magnetic field written in terms of a magnetic vector potential \(\textbf{A}\). For closure conditions, Eq. (2) must be supplied by an equation which describes the magnetic fluctuations via \(\delta \textbf{A}\). However, magnetic fluctuations can arise over a wide range of timescales, from sub-ion/kinetic scales (\(\lesssim\) 1 s), passing through the turbulent inertial range (up to a few hours), and going towards longer ones 33. Here we are interested in the longest timescales which we relate to a space-climatic feedback induced by the magnetic solar cycle over solar wind plasma parameters. At these long timescales, fluctuations \(\delta A\) can be easily described using a dynamo model mimicking the large-scale magnetic field dynamics (see Section Methods). By reasonably assuming that the solar wind fluctuations do not actively affect the generation of the magnetic field via the dynamo mechanism, the time evolution of solar wind velocity fluctuations can be rewritten via a simple ODE

By comparing (3) and (2), we identify \(\beta\) as \(\beta = V/R\) (with V and R representing a characteristic velocity and distance, respectively), with \(\beta\) eventually depending on distance via the Parker model (Eq. (1)), and we introduce a force per mass unit f(t) generating the fluctuations which, in our case, mimics the magnetic solar cycle. Indeed, since \(\delta A(t) \sim R_\odot B_\phi (t)\), being \(B_\phi\) the toroidal large-scale magnetic field generated by the dynamo action (Eq. (9)), then f(t) can be written as

In the trivial case, when the velocity fluctuations are not sustained by a dynamo action (\(f(t) = 0\)), \(\delta v\) exponentially decays as \(\sim \exp (-\beta t)\). Thus, the parameter \(\beta ^{-1} = R/V\) represents the characteristic relaxation time of fluctuations, namely a sort of space-climatic feedback on the stationary solar wind velocity profile by the magnetic solar cycle. In other words, when we perturb the stationary wind, the perturbation decays approximately in a time \(\beta ^{-1}\).

When \(f(t) \ne 0\), Eq. (2) can be formally integrated

if the temporal behavior of \(B_\phi (t)\), that can be derived from (9)–(10), is known. Equations (9)–(10) are nonlinear partial differential equations which can be reduced to a Van der Pol–like equation by considering a logistic growth for the \(\alpha\)-quenching 34 (see Eq. (11)). Thus, the phase-space portrait of the Van der Pol oscillator 35, which is a limit cycle whose distortion from the circular path depends on the parameter \(\mu\) (see Eq. (12)), is now recovered for the toroidal component \(B_\phi (t)\). The existence of a limit cycle in a dynamical system means that the state variable(s) are oscillating function(s) over time. Thus, as a first approach we then introduce a simple periodic term for the magnetic solar cycle, say \(f(t) = f_0 \cos (\omega t)\) which reproduces the limit-cycle of the dynamo model generating the solar cycle for a suitable choice of \(\omega\) (see Section Methods). Under this assumption for f(t), Eq. (5) can be easily solved

Thus, our simple model clearly evidences that a periodic forcing f(t), as the solar magnetic cycle, is able to induce large-scale fluctuations in the solar wind velocity \(\delta v\) which are out of phase with respect to the periodic solar cycle forcing. More specifically, the out-of-phase lag is \(\Delta t = \omega ^{-1} \tan ^{-1}(\omega /\beta )\) which is a function of the period of the forcing \(\omega ^{-1}\) as well as of the unknown space-climatic feedback \(\beta\).

Results

First of all, by using a value for the velocity V at a given distance R and the value of the Schwabe cycle \(\omega = (2\pi / 11)\) yr\(^{-1}\), we can obtain a rough estimate of the expected delay \(\Delta t\). On one side, this effectively proves the natural existence of a time lag, intrinsically hidden in the formulation of the equation of motion for a hydromagnetic gas if it is sustained by a periodic dynamo action. However, these considerations alone cannot be used to explain the amount of time-delay of \(\Delta t \simeq 3.2\) yr observed at a radial distance of about 1 AU. In particular we are not considering any possible mutual dependence between V and R, as depicted by the Parker model (Eq. (1)). Thus, we use the Parker stationary solution for the background radial profile of the solar wind velocity (1) to provide a reasonable estimate of the radial distance dependence of the parameter \(\beta\) and, consequently, to more precisely compare the amount of the phase-shift \(\Delta t\) with respect to observations. As expected (see Fig. 2), since the solar wind velocity tends to slow down with distance, the feedback time required to slow down fluctuations increases at large distances from the Sun. In other words, in absence of a driving force, fluctuations are slowed down meanwhile the solar wind has flowed up, even to relatively large distances.

However, what we have introduced so far represents a zeroth-order approximation, only considering the Schwabe cycle as a sustaining source of the dynamo action, and by neglecting any possible smaller-scale variations such as Quasi-Biennal Oscillations (QBOs) 36,37,38. Hence, there is room for possible improvement of our model. By exploiting recent findings on the observed dependence of the time-delay on the solar cycle23,24, we assume a linear dependence of the phase on the solar cycle by using a periodic cycle with phase modulation due to QBOs (see Section Methods). Thus, we modify the functional form of the forcing as \(f(t) = f_0 \cos [\omega t + \varphi (t)]\), where \(\varphi (t) = \varphi _0 + kt\), and being \(\omega = 2 \pi /22\) yr\(^{-1}\) and \(k = 2 \pi /2.5\) yr\(^{-1}\). In this case from (5) we obtain

where \(\hat{\omega } = \omega + k\). The difference of phases \(\Delta t\), which is again implicit in Eq. (7), can be calculated as the difference of the zero-crossing times of both f(t) and \(\delta v(t)\), thus obtaining

This result highlights that the expected time-delay is extremely sensitive to the frequency for a fixed space-climatic feedback parameter. To evidence the sensitivity of the time-delay, in Fig. 3 we report a comparison of velocity fluctuations \(\delta v(t)\) and the used forcing f(t) (Eq. 6, top panel; Eq. 7, middle panel) using the value of \(\beta\) calculated for \(R = 200\) AU. We clearly observe (Fig. 3, middle panel) a smaller time-delay for the same \(\beta\) compared to the case where only the Schwabe solar cycle is considered (Fig. 3, top panel).

When comparing the estimated time-delay between f(t) and \(\delta v(t)\), with the latter expressed by Eq. (7), as a function of the distance from the Sun, and by deriving V(R) from the Parker model, we clearly observe that there is an order of magnitude of difference between the case in which \(k=0\) and \(\varphi _0=0\) and that in which we consider \(k=(2\pi /2.5)\) yr\(^{-1}\), being representative of the QBOs dynamics. This result (Fig. 4 left vs. right panels) points to a dependence of the time delay on the frequency of the forcing. Finally, when comparing the time-delay between f(t) and \(\delta v(t)\) as a function of the distance from the Sun, we also observe a dependence from the amplitude of the forcing (Fig. 4 upper vs. lower panels).

Time-delay between f(t) and \(\delta v(t)\), as estimated by comparing the former with the latter expressed by Eq. (7), as a function of the distance from the Sun for two different values of the forcing amplitude (\(f_0 = 0.5\), upper panels; \(f_0 = 0.05\), lower panels). Each point is representative of R and V(R) values as derived from the Parker model. Left panel: Eq. (7) with \(k=(2\pi /2.5)\) yr\(^{-1}\) and \(\varphi _0=0\); Right panel: Eq. (7) with \(k=0\) and \(\varphi _0=0\).

Discussion and conclusions

We introduced a simple model and some variants to explore the relationships between solar magnetic activity and solar wind dynamics in terms of an observed time-delay between these two phenomena. Indeed, by analyzing data from the past five solar cycles it has been recently shown 23,24 a consistent lag of approximately 3.2 years between the Ca II K index, a proxy for solar magnetic activity, and solar wind speed.

Starting from the Parker model for solar wind expansion 30, and using a simple model for the solar magnetic cycle, we devised a linear model to understand how fluctuations in solar wind velocity, driven by a self-sustained magnetic solar dynamo which reproduces the solar magnetic activity, manifest themselves through a time-delay with respect to the driving. The key result of the paper is that out-of-phase velocity fluctuations of the solar wind represents the natural response to the magnetic solar cycle, thus to be considered a kind of space-climatic feedback to the solar cycle. This proves the natural existence of a time lag between solar magnetic activity and solar wind dynamics, intrinsically hidden in the formulation of the equation of motion for a hydromagnetic gas if it is sustained by a periodic dynamo action. In absence of the solar cycle driving any fluctuation slow down meanwhile the solar wind flows away from the Sun. According to our model, the unknown space-climatic feedback parameter is not fixed, but can be estimated by using the Parker model.

However, these considerations alone are not able to to fully capture the observed time-delay, claiming for additional factors and/or missing aspects. To address these, since by only considering the Schwabe cycle as a sustaining source of the dynamo action represents a zeroth-order approximation, we improve our model on the dependence of the time-delay on the solar cycle, by inserting a possible small-scale (with respect to the Schwabe cycle) modulation 23,24. Then, we assume a linear dependence of the phase on the solar cycle by using a periodic cycle with phase modulation due to smaller-scale variations such as Quasi-Biennal Oscillations (QBOs). By modifying the forcing function in the model to include QBOs, a refined equation for solar wind velocity fluctuations is derived, yielding in a closer match to observed time-delays. Indeed, when we examine the estimated time-delay by also incorporating QBOs dynamics, i.e., by considering two different contributions at different characteristic timescales, the model reveals an order of magnitude difference in depicted time-delays with respect to the case of only considering the Schwabe solar cycle.

Our results highlight the significance of accounting for smaller-scale variations, such as QBOs, in understanding the complex interplay between solar magnetic activity and solar wind dynamics. The refined model not only provides a more accurate depiction of the observed time-delay but also offers insights into the underlying mechanisms driving these phenomena and future research outlooks and refinements. However, we need to remark that additional refinements on our model can be included, since the seminal model introduced by Parker has some limitations for describing fast (alfvénic) solar wind39, as well as, to further properly introduce solar wind expansion mechanisms by relaxing the isothermal description of the solar corona, then introducing a polytropic expansion model40. Nevertheless, our study evidences the importance of refining models to capture this intricate dynamics by incorporating additional factors such as QBOs to offer a more comprehensive understanding of the observed time-delay between solar magnetic activity and solar wind dynamics, which, from the modeling point of view, emerges from the advection term balancing the periodic forcing. This can advance our understanding of long-term effects of solar activity on solar wind variations, and consequently on interactions of the latter with planetary environments. Indeed, the recent launch of several space missions41, e.g., Parker Solar Probe, Solar Orbiter, BepiColombo, can provide a further test for our modeling results within the inner Heliosphere, offering unique opportunities for radial evolution of the solar activity42,43 and for testing new and/or refined simple models of evolution40.

Methods

As it is well known44, the generation and maintenance against Ohmic dissipation of the solar magnetic field, is well described by the \(\alpha \Omega\)-dynamo effect, where, using spherical coordinates with r being the radial coordinate, the generation of poloidal magnetic field is generated by an average electromotive force induced by the toroidal field (the \(\alpha\)-effect), and the toroidal field is generated by the differential rotation of the sun coupled to the poloidal field (\(\Omega\)-effect). The equation describing this kind of dynamo can be obtained by using the usual induction equation for the variables \(B_\phi\) and \({B}_p = \mathbf {\nabla } \times (A_p\textbf{e}_\phi )\), which represent the axisymmetric toroidal and poloidal field, respectively44

where \(\Omega (r,\theta )\) is the differential angular velocity of the sun in the tachocline, \(\textbf{u}_p\) is the poloidal component of the average velocity field of the rotating plasma, and \(\eta\) is the magnetic diffusivity coefficient44,45.

To obtain a realistic model, we must consider two further effects, which are not described within the simplified induction equation. First of all, we considered an \(\alpha\)-effect which is constant, thus describing a unlimited growth of \(B_p\). When the growing dynamo-generated mean magnetic field \(B_\phi\) reaches a magnitude such that its energy per unit volume is comparable to the kinetic energy of the underlying turbulent fluid motions, the dynamo effect must saturate44. This can be modeled by introducing an ad hoc nonlinear dependence of \(\alpha\) on the mean field \(\alpha \rightarrow \alpha (B_\phi )\) to describe the back-reaction of the toroidal field on \(\alpha\). A simple way to consider this \(\alpha\)-quenching is to introduce a logistic growth for \(\alpha\), namely

where \(B_\star\) is the saturation level of the toroidal field and \(\alpha _0\) is a characteristic turbulent velocity. As the toroidal field increases, the \(\alpha\)-effect tends to zero thus avoiding the unlimited growth of the magnetic field. Further, once the magnetic field is generated in the tachocline, it is removed by a magnetic buoyancy effect, because the magnetic pressure is greater than the kinetic pressure, thus generating a magnetic flux at the bottom of the convective layer46. This effect can be introduced by modeling the removal through \(\partial B_\phi /\partial t \sim -\Gamma (B_\phi ) B_\phi\), where the removal rate is proportional to the magnetic pressure \(\Gamma \sim \gamma B_\phi ^2/(8 \pi \rho )\) through a coefficient \(\gamma\) (while \(\rho\) is the plasma density). The buoyancy term47 must be addend to the r.h.s. of Eq. (9).

We introduce a characteristic length of the upper convective region \(\ell _0 = \epsilon R_\odot\), where \(R_\odot\) is the radius of the sun, which can be used to introduce dimensionless fields \(B_\phi /\alpha _0 \sqrt{4\pi \rho }\) and \(A_p/\alpha _0 \ell _0 \sqrt{4\pi \rho }\). Furthermore, we introduce a characteristic time \(\tau _0 = \ell _0/\alpha _0\) such that \(\Omega _0 = \Omega \tau _0\) and \(S = \ell _0 \alpha _0/\eta\) is the magnetic Reynolds number. Then, by introducing a relaxation time \(t_\alpha\) for the \(\alpha\)-quenching, we obtain \(B_\star ^2 = 4 \pi \rho \ell _0 \alpha _0/t_\alpha\). We are interested to introduce a simplified model for the dynamo action, then we adopt a severe truncation of the dynamo equation48,49 by considering only the large-scale of the dynamo effect, which consists in replacing gradients by \(\nabla \sim \ell _0^{-1}\). Equations (9) and (10), after some algebra, reduce to a nonlinear second-order ODE equation for the toroidal magnetic field

where the free parameters are defined as \(\omega _0^2 = (u_p/\alpha _0 - 1/S)^2 - \Omega _0/\epsilon\), \(\mu = 2 (u_p/\alpha _0 - 1/S)\), \(\xi = \gamma \ell _0 \alpha _0 / \mu\), and \(\lambda = \Omega _0 t_\alpha /(\tau _0 \epsilon ) - (u_p/\alpha _0 - 1/S)\gamma \ell _0 \alpha _0\). Note that for a typical turbulent plasma the magnetic Reynolds number is very high, thus \(u_p/\alpha _0 \gg 1/S\).

Equation (12) is very interesting because it represents a Van der Pol nonlinear oscillator48,49, forced through a cubic term, which can be derived for modelling long-term variations of solar activity at different scales50. When \(\lambda = 0\), the Van der Pol oscillator exhibits a dynamic made by an harmonic term with a frequency \(\omega _0\), and a damping term with a non constant damping rate \(\mu (3\xi B_\phi ^2 - 1)\). Naively, when \(0 \le B_\phi ^2 < (3\xi )^{-1}\) the damping tends to puts the system towards the trivial solution \(B_\phi = 0\) (representing the absence of dynamo action). On the contrary, when \(B_\phi ^2 > (3\xi )^{-1}\), the system bifurcates towards a limit cycle (representing the occurrence of the dynamo action), with a frequency \(\omega ^2 = \omega _0^2\), given by the ratio between the poloidal velocity of plasma and the characteristic velocity of turbulent fluctuations which generate the \(\alpha\)-effect. Even in presence of the forcing term the limit cycle survives. In fact, Eq. (12) can be written as a general \(2 \times 2\) system for the variables \((x,y) = (B_\phi , dB_\phi /dt)\)

where \(f(x,y) = \mu (3\xi x^2-1)\) and \(g(x) = x(\omega _0^2 + \lambda x^2)\). The system (13) satisfies the following conditions: (i) there exists a parameter \(a = \sqrt{1/3\xi }\) such that \(f(x,y) > 0\) when \(x > a\); (ii) the function \(f(0,0) = -\mu\), namely \(f(x,y) < 0\) near the origin; (iii) the function \(g(0) = 0\) and \(\text {sign}[g(x)] = \text {sign}[x]\) when \((u_p/\alpha _0) > (\Omega _0/\epsilon )(t_\alpha /\tau _0)\); iv) the function G(x), defined by

tends to \(G(x) \rightarrow \infty\) when \(x \rightarrow \infty\).

Under these conditions, the system (13) satisfies the Poincaré–Bendixson Theorem51 which assures the existence of a unique limit cycle, namely a unique closed trajectory for \(B_\phi\), centered on the origin49. When \(\mu \ll 1\) the closed trajectory in the phase-space is quite harmonic, so that we can assume a sinusoidal limit cycle \(B_\phi = b \cos \omega t\). Using Eq. (12) and disregarding high-order harmonics \(\sin 3\omega t = \cos 3 \omega t \simeq 0\), we obtain the constant amplitude of the limit cycle \(b \simeq (4/3 \xi )^{1/2}\), which depends on the parameter \(\xi\), and its frequency \(\omega ^2 = \omega _0^2 +\lambda /\xi\). One of the effect of the buoyancy force, in the simplified model, is to change the natural frequency of the dynamo oscillation.

The model (12) represents an autonomous ODE. However the solar cycle is affected by quasi-biennal oscillations (QBOs) on timescales from 1.5 years to 3.5 years52. These oscillations can be associated with flux migration in the poleward direction for both meridional and radial components of the magnetic field53. Moreover, QBOs seem to be located in the profound layers of the Sun54. To model this effect, which can be seen as a secondary dynamo54, we can assume that the parameter \(\lambda\) should be a time-dependent function \(\lambda (t)\), thus making non autonomous the system (12). Changing \(\lambda\) can affect the phases of the limit cycle55, so, as a simplest approach, we guess \(B_\phi (t) = b \cos [\omega t + \varphi (t)]\). By using this ansatz in Eq. (12) and disregarding as before the high-order harmonics, we obtain the same value of b as before, and an equation for the phase \(\varphi (t)\)

where \(\varphi ^\prime = d\varphi /dt\). By conjecturing a weak dependence on time for the phase \(\varphi (t)\), namely \(\varphi (t) \simeq \varphi _0 + k t + \epsilon t^2\), we obtain

A phase modulation for the limit cycle is then possible when \(\lambda\) is not constant, namely when \(\epsilon \not = 0\). On the contrary, when \(\epsilon = 0\), the frequency of the limit cycle results from

Data availibility

The time series of the Ca II K index uses SOLIS data obtained by the NSO Integrated Synoptic Program (NISP), downloaded from the SOLIS website (https://solis.nso.edu/0/iss/). NISP is managed by the National Solar Observatory, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), Inc. under a cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation. The OMNI data are available from Coordinated Data AnalysisWeb (CDAWeb; http://cdaweb.gsfc.nasa.gov).

References

Hathaway, D. H. The Solar Cycle. Living Rev. Solar Phys. 7, 1. https://doi.org/10.12942/lrsp-2010-1 (2010).

Usoskin, I. G. A history of solar activity over millennia. Living Rev. Solar Phys. 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41116-017-0006-9 (2017).

Vecchio, A., Lepreti, F., Laurenza, M., Alberti, T. & Carbone, V. Connection between solar activity cycles and grand minima generation. Astron. Astrophys. 599, A58 (2017).

Biswas, A., Karak, B. B., Usoskin, I. & Weisshaar, E. Long-term modulation of solar cycles. Space Sci. Rev. 219, 19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-023-00968-w (2023).

Mursula, K., Usoskin, I. G. & Maris, G. Introduction to space climate. Adv. Space Res. 40, 885–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2007.07.046 (2007).

Schwenn, R. Space weather: The solar perspective. Living Rev. Solar Phys. 3, 2. https://doi.org/10.12942/lrsp-2006-2 (2006).

Penza, V. et al. Total solar irradiance during the last five centuries. Astrophys. J. 937, 84. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ac8a4b (2022).

Lean, J. L. & Brueckner, G. E. Intermediate-term solar periodicities: 100–500 Days. Astrophys. J. 337, 568. https://doi.org/10.1086/167124 (1989).

Chowdhury, P., Khan, M. & Ray, P. C. Intermediate-term periodicities in sunspot areas during solar cycles 22 and 23. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 392, 1159–1180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.14117.x (2009).

Roy, S., Prasad, A., Panja, S. C., Ghosh, K. & Patra, S. N. A search for periodicities in F10.7 solar radio flux data. Solar Syst. Res. 53, 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0038094619030031 (2019).

Kotzé, P. B. Rieger periodicity behaviour in solar Mg II 280 nm spectral emission. Sol. Phys. 296, 44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-021-01786-5 (2021).

King, J. H. Solar cycle variations in IMF intensity. J. Geophys. Res. 84, 5938–5940. https://doi.org/10.1029/JA084iA10p05938 (1979).

Neugebauer, M. Observations of solar-wind helium. Fundam. Cosm. Phys. 7, 131–199 (1981).

El-Borie, M. A. On long-term periodicities in the solar-wind ion density and speed measurements during the period 1973–2000. Sol. Phys. 208, 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020585822820 (2002).

Dmitriev, A. V., Suvorova, A. V. & Veselovsky, I. S. Statistical characteristics of the heliospheric plasma and magnetic field at the earth’s orbit during four solar cycles 20–23. arXiv e-prints[SPACE]arXiv:1301.2929, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1301.2929 (2013).

Li, K. J., Zhang, J. & Feng, W. Periodicity for 50 yr of daily solar wind velocity. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 472, 289–294. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stx1904 (2017).

Hajra, R., Marques de Souza Franco, A., Echer, E. & José Alves Bolzan, M. Long-term variations of the geomagnetic activity: A comparison between the strong and weak solar activity cycles and implications for the space climate. J. Geophys. Res. 126, e2020JA028695. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JA028695 (2021).

Köhnlein, W. Cross-correlation of solar wind parameters with sunspots (‘Long-term variations’) at 1 AU during cycles 21 and 22. Astrophys. Space Sci. 245, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00637804 (1996).

Li, K. J., Zhanng, J. & Feng, W. A statistical analysis of 50 years of daily solar wind velocity data. Astron. J. 151, 128. https://doi.org/10.3847/0004-6256/151/5/128 (2016).

Venzmer, M. S. & Bothmer, V. Solar-wind predictions for the parker solar probe orbit. Near-sun extrapolations derived from an empirical solar-wind model based on Helios and OMNI observations. Astron. Astrophys. 611, 36. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201731831 (2018).

Samsonov, A. A. et al. Long-term variations in solar wind parameters, magnetopause location, and geomagnetic activity over the last five solar cycles. J. Geophys. Res. 124, 4049–4063. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA026355 (2019).

Reda, R. et al. The exoplanetary magnetosphere extension in Sun-like stars based on the solar wind-solar UV relation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 519, 6088–6097. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stac3825 (2023).

Reda, R., Giovannelli, L. & Alberti, T. On the time lag between solar wind dynamic parameters and solar activity UV proxies. Adv. Space Res. 71, 2038–2047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2022.10.011 (2023).

Reda, R., Stumpo, M., Giovannelli, L., Alberti, T. & Consolini, G. Disentangling the solar activity-solar wind predictive causality at Space Climate scales. Rendiconti Lincei. Sci. Fisiche Nat. 35, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12210-023-01213-w (2024).

Perri, B., Brun, A. S., Strugarek, A. & Réville, V. Dynamical coupling of a mean-field dynamo and its wind: Feedback loop over a stellar activity cycle. Astrophys. J. 910, 50. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/abe2ac (2021).

Fox, N. J. et al. The solar probe plus mission: Humanity’s first visit to our star. Space Sci. Rev. 204, 7–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-015-0211-6 (2016).

McComas, D. J. et al. The three-dimensional solar wind around solar maximum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1517. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL017136 (2003).

Tsurutani, B. T. et al. Corotating solar wind streams and recurrent geomagnetic activity: A review. Journal of Geophysical Research (Space Physics) 111, 0701. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JA011273 (2006).

Bertello, L., Pevtsov, A., Tlatov, A. & Singh, J. Correlation between sunspot number and Ca II K emission index. Sol. Phys. 291, 2967–2979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-016-0927-9 (2016).

Parker, E. N. Dynamics of the interplanetary gas and magnetic fields. Astrophys. J. 128, 664. https://doi.org/10.1086/146579 (1958).

Parker, E. N. Dynamical theory of the solar wind. Space Sci. Rev. 4, 666–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00216273 (1965).

Parker, E. N. A kinematical theory of turbulent hydromagnetic fields. Astrophys. J. 138, 226. https://doi.org/10.1086/147629 (1963).

Bruno, R. & Carbone, V. Turbulence in the Solar Wind, Vol. 928 (2016).

Moffatt, H. K. Magnetic field generation in electrically conducting fluids (1978).

van der Pol Jun., B. Lxxxviii. on “relaxation-oscillations”. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 2, 978–992, https://doi.org/10.1080/14786442608564127 (1926).

Popova, E. P. & Yukhina, N. A. The quasi-biennial cycle of solar activity and dynamo theory. Astron. Lett. 39, 729–735. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063773713100046 (2013).

Vecchio, A., Laurenza, M., Meduri, D., Carbone, V. & Storini, M. The dynamics of the solar magnetic field: Polarity reversals, butterfly diagram, and quasi-biennial oscillations. Astrophys. J. 749, 27. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/749/1/27 (2012).

Vecchio, A. & Carbone, V. Spatio-temporal analysis of solar activity: main periodicities and period length variations. Astron. Astrophys. 502, 981–987. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200811024 (2009).

Belcher, J. W. ALFVÉNIC wave pressures and the solar wind. Astrophys. J. 168, 509. https://doi.org/10.1086/151105 (1971).

Shi, C. et al. Acceleration of polytropic solar wind: Parker Solar Probe observation and one-dimensional model. Phys. Plasmas 29, 122901. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0124703 (2022).

Raouafi, N. E. et al. Parker solar probe: Four years of discoveries at solar cycle minimum. Space Science Reviews[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-023-00952-4 (2023).

Alberti, T. et al. On the scaling properties of magnetic-field fluctuations through the inner heliosphere. Astrophys. J. 902, 84. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/abb3d2 (2020).

Alberti, T., Benella, S., Consolini, G., Stumpo, M. & Benzi, R. Reconciling parker solar probe observations and magnetohydrodynamic theory. Astrophys. J. Lett. 940, L13. https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/aca075 (2022).

Charbonneau, P. Dynamo models of the solar cycle. Living Rev. Solar Phys. 17, 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41116-020-00025-6 (2020).

Zeldovich, I. B. & Ruzmaikin, A. A. Dynamo problems in astrophysics. Astrophys. Space Phys. Rev. 2, 333–383 (1983).

Stix, M. The solar dynamo. Geophys. Astrophys. Fluid Dyn. 62, 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/03091929108229134 (1991).

Biswas, A., Karak, B. B. & Cameron, R. Toroidal flux loss due to flux emergence explains why solar cycles rise differently but decay in a similar way. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 241102. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.129.241102 (2022).

Mininni, P. D., Gómez, D. O. & Mindlin, G. B. Stochastic relaxation oscillator model for the solar cycle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 5476–5479. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.5476 (2000).

Pontieri, A., Lepreti, F., Sorriso-Valvo, L., Vecchio, A. & Carbone, V. A simple model for the solar cycle. Sol. Phys. 213, 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023227503176 (2003).

Karak, B. B. Models for the long-term variations of solar activity. Living Rev. Solar Phys. 20, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41116-023-00037-y (2023).

Jordan, C. & Montesinos, B. Relations between chromospheric and coronal structure, flux-flux correlations and convective zone properties. In Cool Stars, Stellar Systems and the Sun Vol. 291 (eds Linsky, J. L. & Stencel, R. E.) 146–149 (Springer, 1987).

Vecchio, A. & Carbone, V. On the origin of the double magnetic cycle of the Sun. Astrophys. J. 683, 536–541. https://doi.org/10.1086/589768 (2008).

Vecchio, A., Laurenza, M., Meduri, D., Carbone, V. & Storini, M. The dynamics of the solar magnetic field: Polarity reversals, butterfly diagram, and quasi-biennal oscillations. Astrophys. J.[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/749/1/27 (2012).

Fletcher, S. et al. A seismic signature of second dynamo?. Astrophys. J. Lett. 718, L19–L22. https://doi.org/10.1088/2041-8205/718/1/L19 (2010).

Vecchio, A., Laurenza, M., Carbone, V. & Storini, M. Quasi-biennal modulation of the solar neutrino flux and solar and galactic cosmic rays by solar cyclic activity. Astrophys. J. Lett. 709, L1–L5. https://doi.org/10.1088/2041-8205/709/1/L1 (2010).

Acknowledgements

V.C. acknowledges funding from the S.C.A.R.L. Space-It-Up, funded by ASI and MUR. T.A. acknowledges funding from the “Bando per il finanziamento di progetti di Ricerca Fondamentale 2022” of the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) - Mini Grant: “The predictable chaos of Space Weather events”. We acknowledge fruitful suggestions by two anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.C. and T.A. conceived and developed the model, R.R. prepared the figures and R.R. and L.G. analysed the data. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carbone, V., Alberti, T., Reda, R. et al. Space-climatic feedback of the magnetic solar cycle through the interplanetary space. Sci Rep 14, 19850 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70583-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70583-4