Abstract

Natural plant extracts offer numerous health benefits for rabbits, including improved feed utilization, antimycotic and antiaflatoxigenic effect, antioxidants, immunological modulation, and growth performance. The aim of the current study was to investigate the effects of silymarin on the performance, hemato-biochemical indices, antioxidants, and villus morphology. A total of 45 Moshtohor 4 weeks old weaned male rabbits were randomly allocated into three groups (15 rabbit/each) each group with 5 replicates. The first group served as the control group feed on an infected diet by aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) 0.02 mg/kg BW, while the second and third groups received an infected diet by AFB1 (0.02 mg/kg BW) and was treated with Silymarin 20 mg/kg BW/day or 30 mg/kg BW/day, respectively. Regarding the growth performance, silymarin supplementation significantly improved the final body weight compared with the control group. Physiologically, silymarin induced high level of dose-dependent total red blood cell count, hematocrit, eosinophils, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, superoxid dismutase, catalase activity, total antioxidant capacityand intestinal villi width and length. Moreover, silymarin significantly restricted oxidative stress indicators, malondialdehyde, Alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total cholesterol, triglyceridein rabbits treated with (AFB1). In conclusion, silymarin supplementation to AFB1 contaminated rabbit diet may mitigate the negative effect of AFB1 on the rabbit performance and health status and increase growth performance, average daily gain, immunological modulation and antioxidants and provide a theoretical basis for the application of silymarin in livestock production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mycotoxins in cereal products based on the chemical and physical character of the product, storage, processing, rainfall, temperature, humidity and insects1,2,3. Aflatoxins are secreted by various species of fungus Aspergillus, such as A. parasiticus, A. numius, A. pseudotamarii, and A. flavus. Aflatoxin B1 is considered the most crucial and frequently observed mycotoxins due to its high toxicity4. It causes oxidative damage through intense production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that change proteins, DNA and lipids of cellular contents5.

Rabbits provide an outstanding source of protein for human consumption. Therefore, many researchers are trying to improve rabbit meat production by selecting high growth rate rabbits with better carcass and meat quality6,7,8. Rabbits are one of the most susceptible animals to toxins such as aflatoxins9. Mycotoxicosis in rabbits may lead to considerable reductions in feed intake (up to 60%), delaying growth and resulting in poorer performance and economic loss.

Dietary additives are ingredients used in animal nutrition to improve the feed, nourishment, health and performance of animals10. Furthermore, feed additives may not be placed on the market unless a scientific review demonstrates that the additive has no negative effects on human or animal health or the environment. Feed additives are widely used in animal feed for a variety of purposes, including antitoxins, anticoccidial medicines and growth boosters8,10. ROS generation is regarded as a pathobiochemical mechanism implicated in the onset or progression of a variety of diseases, including atherosclerosis, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, and the initiation of carcinogenesis or liver ailments11.

Phytotherapy is a herbal medicine that is used instead of antibiotic medicine12. Silymarin (flavonolignan) is derived from "milk thistle seeds" (Silybum marianum). It comprises of flavonoids (silidianin, silychristin, isosilibin, silidianin, silichristin and silybin) that showed antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, anti-lipid peroxidative, immunological stimulant, hepatic cell stabilizing effects and treat cirrhosis13,14,15. Silymarin induces hepatic cells synthesis of ribosomal RNA to encourage protein production16 and stops the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production from isolated neurons of Kupffer and the perfused rat liver17.

Activation of AFB1 in human and rat liver is a complex operation dominated by multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes18,19. Silymarin is a potent antioxidant with hepatoprotective character that prevents the cytochrome P450 system, beats the free radicals and affects the enzymatic systems related to glutathione and superoxide dismutase, consequently inhibits AFB1 activation and elicited changes in liver20,21,22. Therefore, the current study aimed to evaluate the influence of silymarin as an anti-aflatoxin on growth, biochemical performance, and antioxidant markers in rabbits.

Materials and methods

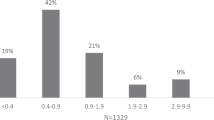

Chromatographic condition for AFB1 determination

High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) was used to estimate AFB1 in the feed compared to the standard23. The HPLC‐ chromatogram of AFB1 and standard are presented in Fig. 1. The operation conditions were Column packing: Use ODS gel (particle size 3–5 μm) 4.6 mm in inner diameter, 150 mm or 250 mm in length, temperature: 40 °C Mobile phase: Acetonitrile/ methanol/ water (1: 3: 6). Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min, wavelength: Were 365 nm for excitation and 450 nm for emission. AFB1 Standard: Catalog Number: A6636 Potency: ≥ 98% Company: Sigma- Aldrich.

Animals, experimental design, and environmental data

This study was performed at Faculty of Agriculture, Benha University, Egypt, after the approval of Local Experimental Animal Care Committee (REC-FOABU.16000/3) with confirming that all procedures were done in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The animals were kept under the standard operating procedures of the University of Benha. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

A total of 45 Moshtohor four weeks old weaned male rabbits (developed from crossing between V-line and Gabali)24 with an average body weight of 500 ± 5 g were randomly allocated into three treatments, each of which replicated five times with three animals per replicate in cages (45 × 55 × 30 cm) to the end of the experiment (8 weeks). The first group (AF) served as the control group was fed on diet infected with 0.02 mg aflatoxin B1/kg BW, while the second and third groups received diet infected with 0.02 mg aflatoxin B1/kg BW and treated with Silymarin 20 mg/kg BW/day (second group) or 30 mg/kg BW/day (third group). Supplementations were given orally daily during the experiment period. During the experimental period, rabbits were fed the same standard iso-caloric/iso-nitrogenic diet. The basal diet composition and calculated analysis were performed in accordance with the Nutritional Research Council Nutrient Requirements of Rabbits25 as shown in Table 1.

Growth performance

Weaned rabbits in each replicate were weighed at 4, 8, 12 weeks of age using a digital scale and the average daily weight gain (ADG (g/weaned rabbit) was calculated. At the end of the experiment, the carcass characteristics were assessed (For more details see26). In addition, rabbit Musculus Longissimus lumborum (LL) was dissected and the liver was cleaned and frozen at – 80 °C for assessment of meat quality and antioxidant status.

Meat quality parameters

Right and left Longissimus lumborum muscles (LL) were collected to determine the pH, water holding capacity (WHC), drip loss, thawing and cooking loss (samples taken 10 min to reach 75 °C in preheated water bath), Warner–Bratzler Shear Force (WBSF), lightness (L*), redness (a*), yellowness (b*), chroma (C), and Hue angle (h)27. Additionally, moisture contents were assessed by AOAC28. The keeping quality of rabbits meat was evaluated over 10 days (For more details see26,29), then APC was determined and pH was measured ( For more details see26,30).

Hematological and biochemical parameters

At the end of the experimental period, two blood samples were collected. The first sample was collected with anticoagulant (EDTA) to determine hematocrit (HCT), hemoglobin (Hgb), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCHC), total red blood cell count (RBC) and total white blood cell count (WBC)31. The second sample was collected without anticoagulant, and the serum stored at − 20 °C until the biochemical parameters measured (For more details see26). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were determined Morgenstern et al.32. Serum total cholesterol, triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were spectrophotometrically assessed using commercial kits developed by Pasteur laboratories (Egyptian American Co. for Laboratory Services, Egypt).

Antioxidant profile

Rabbit's livers were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution (pH 7.4 with 0.16 mg/ml heparin) to eliminate any red blood clots. The liver was homogenized in 5 mL of cold PBS per gram of tissue (1:5 dilution). Samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min. Supernatants were collected and stored at − 20 °C until biochemical analysis of superoxid dismutase (SOD)33, catalase activity34, malondialdehyde (MDA)35 and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) levels36.

Quantitative histomorphometric analysis of jejunum segments

Five Segments of the mid-jejunum (3 cm) from each treatment were collected, fixed with formalin for 48 h and paraffin embedded. Two sections (100 μm) from each sample were obtained, stained with hematoxylin for one min., and counterstained with eosin for 10 s. to assess the maximum villus length (measured from above the crypt to the tip of the villus), villus width, and submucosa/muscularis/serosa thickness. All targeted variables were measured with a camera (OLYMPUS; TH4-200; Tokyo, Japan) coupled with computer-assisted digital-image pro plus (IPP) analysis software (Image-Pro Plus 4.5, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out using PROC GLM37 and expressed as mean value ± SEM. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at P < 0.05. The difference among treatments were tested using Duncan’s multiple range test at P < 0.05. The static model applied is as follow:

where: y is the observations, µ = general mean, Ti: effect of treatment (i = 1, 2 and 3), eij: random error.

Ethical approval

This study was performed at Faculty of Agriculture, Benha University, Egypt, after the approval of Local Experimental Animal Care Committee (REC-FOABU.16000/3) with confirming that all procedures were done in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The animals kept under the standard operating procedures of the University of Benha. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines

Results

Growth performance and carcass traits

The results illustrated that adding silymarin increased (p < 0.05) the BW8, BW12, ADG4-8, ADG 8-12and ADG4-12 compared to the AF group Table 2. The growth performance of rabbits supplemented with Silymarin 20 mg (501.7, 1124.0 and 1684.7 g) and 30 mg (499.3, 1110.0 and 1700 g) were better than the AF group from week 4–8, 8–12 and 4–12, respectively (Table 2). There was no significant difference among the experimental groups regarding the relative weights of carcass cut and internal organs except for the head Table 3.

Physical characteristics and microbial abundance of MLD muscle

The current results did not reveal any significant differences regarding WHC, drip loss (48 h), thawing loss, cooking loss, lightness (L*), redness (a*) and yellowness (b*) and Hue angle (h) of Longissimus Lumborum muscle. While silymarin supplementation decreased shear force with an increase of moisture content when compared with the AF group (P < 0.05). Chroma was increased in the group provided with silymarin 20 mg (P < 0.05) (Table 4), but the pH values were lower than the AF group (P < 0.05).

Blood hematological and biochemical

The effects of silymarin supplementation on hematological and biochemical variables of blood are summarized in Table 5. There were no statistically significant differences of hematological variables among the treated groups except for RBCS, hematocrit, MCV and eosinophils. Rabbits supplemented with Silymarin 20 mg and 30 mg exhibited highest RBS`s count hemoglobin and platelets than those of the AF group. Meanwhile, the group supplemented with Silymarin 20 mg or 30 mg had a significantly lower hematocrit and eosinophils percentage than the AF group. Generally, weaning rabbits supplemented with Silymarin 20 mg or 30 mg revealed a reduction of the total cholesterol, triglyceride, ALT, AST and creatinine than the AF weaning rabbits. The provision of silymarin 30 mg had a significantly increase in the concentration of HDL. Supplementation of silymarin to the diet infected with aflatoxin led to reduce significantly the liver and kidney function compared with the AF group (Table 5).

Antioxidant enzyme activity

Results of antioxidant markers of weaned rabbits as they were influenced by the supplementation are demonstrated in Table 6. Compared with AF group, the levels of SOD, CAT and TAC were increased at week 12 of rabbit provided with silymarin with a reduction of MDA.

Villus morphology and morphometry

Data regarding intestinal morphology of weaned Moshtohor rabbits aged 12 weeks are shown in Table 7 and Fig. 2. Although the NVIS was consistently higher in the additives group, it was not statistically significant. However, the weaned rabbit which received Silymarin 20 mg or 30 mg had a higher villus width and length than those in the AF group. Furthermore, the supplementation of Silymarin 20 mg or 30 mg improved the MTh and G cell at 12 weeks of age rabbit.

Histological image for the impact of dietary silymarin on villus morphology and morphometry of 12 weeks old rabbits fed diet infected with aflatoxin. Rabbits fed on diet infected with 0.02 mg aflatoxin B1/kg BW. aflatoxin B1 + Silymarin 20 mg: Rabbits received diet infected with 0.02 mg aflatoxin B1/kg BW and treated with Silymarin 20 mg/kg BW/day. aflatoxin B1 + Silymarin 30 mg: Rabbits received diet infected with 0.02 mg aflatoxin B1/kg BW and treated with Silymarin 30 mg/kg BW/day.

Discussion

Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is the most abundant hazard metabolite and the most common feed contaminant in many parts of the world. When more than one mycotoxin present in feed, the toxicity and clinical symptoms in animals are complicated and diverse. The exposure duration (acute or chronic), contamination rate of AFB1 in diet, animal species, age, production status, and toxin co-contamination (synergistic effect) may influence animal’s response to the toxin38. Therefore, the current study aimed to evaluate the influence of silymarin as an anti-aflatoxin on growth, biochemical performance, and antioxidant markers in rabbits.

The current results revealed a reduction of the growth performance of rabbits fed diet contaminated with AFB1. These results are in agreement with the results obtained by Farag et al.39; Sun et al.40. The performance deterioration caused by the toxins may be related to several factors such as; (a) decreased feed intake, (b) modification of liver oxygenase enzymes activity that responsible for protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, (c) modification of essential nutrients absorption concurrently with patho-anatomical alterations in vital organs, especially liver41,42,43, (d) toxic influence on the cellular contents via inhibition of protein, RNA and DNA syntheses44, (e) decreased digestibility of nitrogen free extract, ether extract and dry matter, (f) anorexia and lipogenesis45,46.

Supplementation of 20 or 30 mg/kg silymarin in the current study, significantly improved the growth, live body weight and average daily gain compared with AF (control groups). These growth-promoting benefits could be owned to silymarin's hepato-protective and immune-boosting properties. Indeed, it has been proposed that the presence of functional bioactive ingredients in plant extracts, such as flavonoids and phenolic compounds, could improve feed digestibility and nutrient bioavailability. Thereby increasing feed utilization and promoting higher protein synthesis47,48. The growth improvement may be associated with the availability of bioactive functional phytochemicals that might improve feeding intake, feed efficiency, and protein retention. Furthermore, silymarin content may increase protein synthesis via the enzymatic system49. Banaee et al.49 reported that supplementation with S. marianum changes the expression of the growth hormone gene that participates in muscle fibers creation. These results are comparable with Hasheminejad et al.50 who reported that silymarin reduced the toxic effects of AFB1 and the metabolic needs of the digestive tract. Consuming 0.5% S. marianum reduces the pathogenic microorganisms in ileum51.

The current findings regarding the carcass traits revealed numerically improvement by adding silymarin but the differences were non-significant. These results are comparable to others that stated the weights and relative weights of internal organs (spleen, brain, liver and kidney) did not reveal differences between NZW rabbits orally treated with AFB1 and the control group39,52. There were no significant changes in the rheological qualities of rabbit meat when silymarin was added by 20 and 30 mg. This could be because silymarin has powerful antioxidant effects53 by (a) direct free radical scavenging, blocking specific enzymes responsible for free radical production (b) by maintaining the integrity of the electron-transport chain of mitochondria under stress conditions, contributing to the cell's optimal redox status by activating a variety of antioxidant enzymes and non-enzymatic antioxidants. This may be primarily via transcription factors such as nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a protein that regulates the expression of antioxidant proteins that protect against oxidative damage caused by injury and inflammation, and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB)54.

Blood is a connective tissue made up of fluid or plasma sections suspended by elements (erythrocytes, leukocytes, and thrombocytes). Blood connects the body's organs and cells to maintain a continuous cellular environment by circulating through every tissue, giving nutrients, and removing waste materials. The current results explained that there was a significant improvement in RBCs, HCT and Eosinophils due to the treatment with silymarin 20 and 30 mg/kg B.W. compared with the control group. Also, obtained results are in agreement with the finding of Farag et al.39 who reported that rabbits fed on contaminated diet with AFB1 showed higher serum TC, TG and LDL levels compared with the other groups. Silymarin administration resulted in decreased total cholesterol, triglyceride, and increased HDL levels, which could be linked to silymarin's antioxidant action55,56.

Silymarin is lipophilic and highly binds to plasma membrane components, improving plasma membrane strength and reducing membrane rupture and disintegration57. AFB1 can be easily recognized in infected animals' hepatic tissues and it is regarded as one of the most important body organs due to the way it detoxifies or eliminates toxins and foreign materials58. The current results revealed that AF reduced the RBCs and WBCs this was comparable to others59,60 that might be due to the hazard effect of aflatoxin on liver tissues, which in turn caused impairment of hematopoietic tissue61. Moreover, Sun et al.40 stated that male rabbits fed with high level of AFB1 showed decrease of RBC, compared to bucks fed a low level of AFB1 or the control group. This reduction is represented by the anaemic consequence of aflatoxicosis that could be owned to the reduction of serum iron and modified protein metabolism. The hazard impact of AFB1 on hematology was alleviated by silymarin that were orally intake62. Moreover, Abou-Shehema et al.56 observed that cockerels fed diets provided with 25 g Milk thistle/kg diet (equal to 1 g silymarin /kg diet) revealed significantly improved RBCs and WBCs compared to the control group during the summer season.

The effects of AFB1 on the liver were reflected in blood biochemistry data, particularly ALT, AST, and serum proteins. The serum enzyme activity results are in agreement with Hatipoglu and Keskin63, who found that AFB1-intoxicated rats had significantly higher levels of liver enzymes than control rats. Silymarin can impact the metabolism and concentration of lipids in the blood by reducing cholesterol synthesis in the liver and lowering blood cholesterol by limiting its absorption in the gastrointestinal tract64. Obtained results agreed with Sobolová et al.65 who demonstrated that silymarin reduced blood cholesterol and triglycerides and can impact the metabolism and concentration of lipids in the blood by reducing cholesterol synthesis in the liver and lowering blood cholesterol by limiting its absorption in the gastrointestinal tract.

Silymarin protects liver cells from viruses, chemicals, and natural toxins like aflatoxins (fungal toxins). There have been several reports of improved liver function following silymarin prescription (administration)66. It can also prevent the peroxidation processes involved in liver lesions produced by toxins and other hazardous chemicals16. Creatinine is a chemical byproduct of muscle metabolism, when kidneys are healthy; they filter creatinine and other waste products from the blood. Silymarin supplementation in combination with AFB1 improved creatinine by decreasing levels due to the kidney filtration functions. The present results agreed with Ashrafihelan et al.67 who reported that oral therapy of silymarin (13 mg/kg BW) resulted in better kidney function. Antioxidant markers were improved in blood of weaned rabbits due to the use of silymarin + AFB1, this improvement is related to the effect of silymarin as antioxidant.

The liver and kidneys are detoxifying organs (mycotoxins’ metabolism). ALT and AST are used as a chief index to assess liver performance68 because they are released into bloodstream when the liver is damaged. The high levels of AST and ALT are indicators of liver damage69. AF in diet of rabbits elevated the values of ALT and AST in blood as a result of hepatocytes loss of their integrity with destruction of hepatic parenchymal cells. Hassan et al.70 and Farag et al.39 reported that rabbit fed with diet contaminated with AFB1 showed an increase of liver enzymes which supported the current findings. Moreover, AFB1 caused liver cells cirrhosis and necrosis71.

In this study Silymarin supplementation to the diet reduces the liver enzymes when compared with the AF groups. The preserving effect of silymarin on livers of quail and broilers fed diet with AFB1 were reflected by the reduction of liver enzymes56,72.

AFB1 significantly decreased antioxidant enzymes (CAT and GSH) with higher levels of the MDA biomarkers compared to the control group39,70,73,74 The current results regarding the antioxidant enzymes were comparable with the majority of the recent studies. These harmful impact of AFB1 might be related to AFB1 biotransformation to intermediate metabolites of high reactivity (AFB1 8, 9 epoxide) and the release of free radicals including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anions (O2−), and hydroxyl radicals (·OH) involved in oxidative destruction75.

The initiation of oxidative stress and production of ROS may be a leading initiate of damaging outcomes76. ROS arises via the phagocytic properties of immune cells77. The excess of ROS in the body that surpass its capability to remove them will increase the lipid peroxidation levels in several tissues, DNA impairment and deterioration of protein expression5,8,78. The level of oxidative stress is based on the period of contamination, co-contamination, the synergetic effects, toxin values, animal age, species and productive phase79. In vitro; researches revealed that AFB1 elicited downregulation of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GSH-Px and catalase) causing an increase of lipid peroxidation by-products (MDA) and a sharp reduction of GSH76.

Abou-Shehema et al.56 stated that 1 g silymarin/kg diet supplementation significantly improved TAC, GSH, MDA on the summer season compared with the control. Silymarin possess antioxidant properties, blocking enzymes that produce active oxygenated species and improving mitochondrial cohesiveness under stress, thereby reducing free radical damage by increasing the activity of the enzyme superoxide dismutase53. While the current study claims that the improvement in antioxidant indices (MDA, TAC and SOD) is attributable to silymarin, which has antioxidant activity53.

Studying intestinal histomorphology of rabbits is important to understand the rabbit's normal and abnormal physiological state. Normal collected histological sections from rabbits’ intestinal tract revealed an improvement in NVIS, villi breadth, length, and MTH. Recent results indicated that improved intestinal tissue structures and supplements did not cause any damage or abnormal intestinal changes. Our results agreed with Wang et al.80 who found that silymarin supplementation preserved the normal intestinal histology and enhanced the intestinal histomorphometry such as villi length and width. Silymarin is readily absorbed through the gastrointestinal system and achieves peak plasma concentration by 2–4 h. It has a half-life of 6–8hs in most laboratory animals with more than 80% eliminated in bile and some in urine81. Silymarin distention of the gastric mucosa induced by pylorus obstruction increases the vague nerve's production of acetylcholine (Ach), which acts directly on G cells and parietal cells, promoting the secretion of gastrin and histamine, respectively82. To determine the ideal level of silymarin for field use, further research would be necessary, especially in a practical context of rabbit production. The effective doses may vary depending on various factors such as the severity of aflatoxin contamination, the age and health of the rabbits, feed composition, and management conditions.

Conclusion

Silymarin supplementation to weaned rabbit to ameliorate the hazard influences of aflatoxin may lead to an increase in the growth performance and ADG through enhancing villus length and mucus thickness. Moreover, silymarin is an improper supplement to reduce the oxidative stress through increased the antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT and TAC). Therefore, it is recommended to supplement rabbit diets’ with 30 mg Silymarin.

Data availability

The data is available on request. Dr.Tharwat Imbabi Tharwat.mohamed@fagr.bu.edu.eg.

References

Reyneri, A. The role of climatic condition on micotoxin production in cereal. Vet. Res. Commun. 30, 87 (2006).

Zain, M. E. Impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 15(2), 129–144 (2011).

Udomkun, P. et al. Occurrence of aflatoxin in agricultural produce from local markets in Burundi and Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Food Sci. Nutr. 6(8), 2227–2238 (2018).

Tinelli, A., Passantino, G., Perillo, A. & Zizzo, N. Anatomo-pathological consequences of mycotoxins contamination in rabbits feed. Iran. J. Appli. Anim. Sci. 9(3), 379–387 (2019).

Mary, V. S., Theumer, M. G., Arias, S. L. & Rubinstein, H. R. Reactive oxygen species sources and biomolecular oxidative damage induced by aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin B1 in rat spleen mononuclear cells. Toxicology 302(2–3), 299–307 (2012).

Mohammed, H. & Nasr, M. Growth performance, carcass traits, behaviour and welfare of New Zealand White rabbits housed in different enriched cages. Anim. Prod. Sci. 57(8), 1759–1766 (2016).

Nasr, M. A., Abd-Elhamid, T. & Hussein, M. A. Growth performance, carcass characteristics, meat quality and muscle amino-acid profile of different rabbits breeds and their crosses. Meat Sci. 134, 150–157 (2017).

Imbabi, T. A., El-Sayed, A. I., Radwan, A. A., Osman, A. & Abdel-Samad, A. M. Prevention of aflatoxin B1 toxicity by pomegranate peel extract and its effects on growth, blood biochemical changes, oxidative stress and histopathological alterations. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 108(1), 174–184 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Protective effect of SeMet on liver injury induced by ochratoxin a in rabbits. Toxins 14(9), 628 (2022).

Faraz, A. Feed additives and their use in livestock feed. Farmer Reform. 3(10), 10–10 (2018).

Silva, L. F. et al. Research article clinical and pathological changes in sheep during a monensin toxicity outbreak in Brasilia, Brazil. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv 11, 73–78 (2016).

El-Hela, A. A. et al. Dinebra retroflexa herbal phytotherapy: A simulation study based on bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis retraction potential in swiss albino rats. Medicina 58(12), 1719 (2022).

Attia, Y. A. et al. Milk thistle seeds and rosemary leaves as rabbit growth promoters. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 37(3), 277–295 (2019).

Adetuyi, B. O., Omolabi, F. K., Olajide, P. A. & Oloke, J. K. Pharmacological, biochemical and therapeutic potential of milk thistle (silymarin): A review. World News Nat. Sci. 37, 75–91 (2021).

El-Ghany, W. A. A. The potential uses of silymarin, a milk thistle (silybum marianum) derivative, in poultry production system. Online J. Anim. Feed Res. 12(1), 46–52 (2022).

Vargas-Mendoza, N. et al. Hepatoprotective effect of silymarin. World J. Hepatol. 6(3), 144 (2014).

Al-Anati, L., Essid, E., Reinehr, R. & Petzinger, E. Silibinin protects OTA-mediated TNF-α release from perfused rat livers and isolated rat Kupffer cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 53(4), 460–466 (2009).

Forrester, L. M., Neal, G. E., Judah, D. J., Glancey, M. J. & Wolf, C. R. Evidence for involvement of multiple forms of cytochrome P-450 in aflatoxin B1 metabolism in human liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87(21), 8306–8310 (1990).

Gallagher, E. P., Kunze, K. L., Stapleton, P. L. & Eaton, D. L. The kinetics of aflatoxin B1Oxidation by human cDNA-Expressed and human liver microsomal cytochromes P450 1A2 and 3A4. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 141(2), 595–606 (1996).

Valenzuela, A., Aspillaga, M., Vial, S. & Guerra, R. Selectivity of silymarin on the increase of the glutathione content in different tissues of the rat. Planta Med. 55(05), 420–422 (1989).

Mira, L., Silva, M. & Manso, C. Scavenging of reactive oxygen species by silibinin dihemisuccinate. Biochem. Pharmacol. 48(4), 753–759 (1994).

Baer-Dubowska, W., Szaefer, H. & Krajka-Kuzniak, V. Inhibition of murine hepatic cytochrome P450 activities by natural and synthetic phenolic compounds. Xenobiotica 28(8), 735–743 (1998).

Joshua, H. Determination of aflatoxins by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with post-column in-line photochemical derivatization and fluorescence detection. J. Chromatogr. A 654(2), 247–254 (1993).

Iraqi, M., García, M., Khalil, M. & Baselga, M. Evaluation of milk yield and some related maternal traits in a crossbreeding project of Egyptian Gabali breed with Spanish V-line in rabbits. J. Anima. Breedi. Genet. 127(3), 242–248 (2010).

Council, N. R. Nutrient Requirements of Rabbits (1966).

Osman, A. et al. Health aspects, growth performance, and meat quality of rabbits receiving diets supplemented with lettuce fertilized with whey protein hydrolysate substituting nitrate. Biomolecules 11(6), 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11060835 (2021).

Elokil, A. A. et al. Zinc and copper with new triazine hydrazone ligand: Two novel organic complexes enhanced expression of peptide growth factors and cytokine genes in weaned V-line rabbit. Animals 9(12), 1134 (2019).

Horwitz, W. Official Methods of analysis of AOAC International (AOAC International, 2000).

El-Bahr, S. et al. Effect of dietary microalgae on growth performance, profiles of amino and fatty acids, antioxidant status, and meat quality of broiler chickens. Animals 10(5), 761 (2020).

Sabike, I. I., Fujikawa, H. & Edris, A. M. The growth kinetics of salmonella enteritidis in raw ground beef. Biocontrol Sci. 20(3), 185–192 (2015).

Jain NC (1986). Hematological techniques. Schalm's veterinary hematology, 20–86.

Morgenstern, S., Oklander, M., Auerbach, J., Kaufman, J. & Klein, B. Automated determination of serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase. Clin. Chem. 12(2), 95–111 (1966).

Nishikimi, M., Rao, N. A. & Yagi, K. The occurrence of superoxide anion in the reaction of reduced phenazine methosulfate and molecular oxygen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 46(2), 849–854 (1972).

Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 105, 121–126 (1984).

Ohkawa, H., Ohishi, N. & Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 95(2), 351–358 (1979).

Koracevic, D., Koracevic, G., Djordjevic, V., Andrejevic, S. & Cosic, V. Method for the measurement of antioxidant activity in human fluids. J. Clin. Pathol. 54(5), 356–361 (2001).

Institute S. SAS/STAT Software: Changes and Enhancements for Release 6.12 (Sas Inst, 1996)

Yunus, A. W., Razzazi-Fazeli, E. & Bohm, J. Aflatoxin B1 in affecting broiler’s performance, immunity, and gastrointestinal tract: A review of history and contemporary issues. Toxins 3(6), 566–590 (2011).

Farag, M. R. et al. essential oil ameliorated the behavioral, biochemical, physiological and performance perturbations induced by aflatoxin B1 in growing rabbits. Ann. Anim. Sci. 23, 1201–1210 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. The effects of low levels of aflatoxin B1 on health, growth performance and reproductivity in male rabbits. World Rabbit Sci. 26(2), 123–133 (2018).

Clark, J., Jain, A., Hatch, R. & Mahaffey, E. Experimentally induced chronic aflatoxicosis in rabbits. Am. J. Vet. Res. 41(11), 1841–1845 (1980).

Abdelhamid, A., El-Shawaf, I., El-Ayoty, S., Ali, M. & Gamil, T. Effect of low level of dietary aflatoxins on baladi rabbits. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 40(5–6), 517–537 (1990).

Shabani, A., Dastar, B., Khomeiri, M., Shabanpour, B. & Hassani, S. Response of broiler chickens to different levels of nanozeolite during experimental aflatoxicosis. J. Biol. Sci. 10(4), 362–367 (2010).

Marai, I. & Asker, A. Aflatoxins in rabbit production: Hazards and control. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 8(1), 1–28 (2008).

Yu, F.-L. Studies on the mechanism of aflatoxin B1 inhibition of rat liver nucleolar RNA synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 256(7), 3292–3297 (1981).

Oguz, H. & Kurtoglu, V. Effect of clinoptilolite on performance of broiler chickens during experimental aflatoxicosis. Br. Poultry Sci. 41(4), 512–517 (2000).

Citarasu, T. Herbal biomedicines: A new opportunity for aquaculture industry. Aquac. Int. 18(3), 403–414 (2010).

Ahmadifar, E. et al. Benefits of dietary polyphenols and polyphenol-rich additives to aquatic animal health: An overview. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 29(4), 478–511 (2021).

Banaee, M., Sureda, A., Mirvaghefi, A. R. & Rafei, G. R. Effects of long-term silymarin oral supplementation on the blood biochemical profile of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 37, 885–896 (2011).

Hasheminejad, S. A., Makki, O. F., Nik, H. A. & Ebrahimzadeh, A. The effects of aflatoxin B1 and silymarin-containing milk thistle seeds on ileal morphology and digestibility in broiler chickens. Vet. Sci. Dev. 5(2), 6017 (2015).

Kalantar, M., Salary, J., Sanami, M. N., Khojastekey, M. & Matin, H. H. Dietary supplementation of Silybum marianum or Curcuma spp. on health characteristics and broiler chicken performance. Glob. J. Anim. Sci. Res. 2(1), 58–63 (2014).

Ibrahim, K. Effect of aflatoxin and ascorbic acid on some productive and reproductive parameters in male rabbits. Toxicology 162, 209–218 (2000).

Surai, P. F. Silymarin as a natural antioxidant: An overview of the current evidence and perspectives. Antioxidants 4(1), 204–247 (2015).

Varga, Z. et al. Structure prerequisite for antioxidant activity of silybin in different biochemical systems in vitro. Phytomedicine 13(1–2), 85–93 (2006).

Fallah Huseini, H., Zaree, A., Babaei Zarch, A. & Heshmat, R. The effect of herbal medicine Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. seed extract on galactose induced cataract formation in rat. J. Med. Plants 3(12), 58–62 (2004).

Abou-Shehema, B., Rawia, S. H., Khalifah, M. & Abdalla, A. Effect of silymarin supplementation on the performance of developed chickens under summer condition 2-during laying period. Egypt. Poultry Sci. J. 36(4), 1633–1644 (2016).

Basiglio, C. L., Pozzi, E. J. S., Mottino, A. D. & Roma, M. G. Differential effects of silymarin and its active component silibinin on plasma membrane stability and hepatocellular lysis. Chemico-Biol. Interact. 179(2–3), 297–303 (2009).

Khan, S. Evaluation of hyperbilirubinemia in acute inflammation of appendix: A prospective study of 45 cases. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 4(3), 281–289 (2006).

Mogilnaya, O., Puzyr, A., Baron, A. & Bondar, V. Hematological parameters and the state of liver cells of rats after oral administration of aflatoxin B1 alone and together with nanodiamonds. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 5, 908–912 (2010).

Abd Allah, O. A., Fararh, K. M., Farid, A. S. & Gad, F. A. Hematological and hemostatic changes in aflatoxin, curcumin plus aflatoxin and curcumin treated rat. Benha Vet. Med. J. 32(2), 151–156 (2017).

Pepeljnjak, S., Petrinec, Z., Kovacic, S. & Segvic, M. Screening toxicity study in young carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) on feed amended with fumonisin B 1. Mycopathologia 156, 139–145 (2003).

Hassaneen, N. H., Hemeda, S. A., El Nahas, A. F., Fadl, S. E. & El-Diasty, E. M. Ameliorative effects of camel milk and silymarin upon aflatoxin B1 induced hepatic injury in rats. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 15092 (2023).

Hatipoglu, D. & Keskin, E. The effect of curcumin on some cytokines, antioxidants and liver function tests in rats induced by Aflatoxin B1. Heliyon 8(7), e09890 (2022).

Škottová, N. et al. Phenolics-rich extracts from Silybum marianum and Prunella vulgaris reduce a high-sucrose diet induced oxidative stress in hereditary hypertriglyceridemic rats. Pharmacol. Res. 50(2), 123–130 (2004).

Sobolová, L., Škottová, N., Večeřa, R. & Urbánek, K. Effect of silymarin and its polyphenolic fraction on cholesterol absorption in rats. Pharmacol. Res. 53(2), 104–112 (2006).

Hellerbrand, C., Schattenberg, J. M., Peterburs, P., Lechner, A. & Brignoli, R. The potential of silymarin for the treatment of hepatic disorders. Clin. Phytosci. 2(1), 1–14 (2017).

Ashrafihelan, J. et al. High mortality due to accidental salinomycin intoxication in sheep. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 7(3), 173–176 (2014).

Hu, Z. et al. Quantitative liver-specific protein fingerprint in blood: A signature for hepatotoxicity. Theranostics 4(2), 215 (2014).

Yang, L. et al. Toxicity and oxidative stress induced by T-2 toxin and HT-2 toxin in broilers and broiler hepatocytes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 87, 128–137 (2016).

Hassan, A. A. et al. Aflatoxicosis in rabbits with particular reference to their control by N-Acetyl cysteine and probiotic. Int. J. Curr. Res 8(1), 25547–25560 (2016).

Oraby, N. H. et al. Protective and detoxificating effects of selenium nanoparticles and thyme extract on the aflatoxin B1 in rabbits. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 100(3), 284–293 (2022).

Khazaei, R., Seidavi, A. & Bouyeh, M. A review on the mechanisms of the effect of silymarin in milk thistle (Silybum marianum) on some laboratory animals. Vet. Med. Sci. 8(1), 289–301 (2022).

Prabu, P., Dwivedi, P. & Sharma, A. Toxicopathological studies on the effects of aflatoxin B1, ochratoxin A and their interaction in New Zealand White rabbits. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 65(3), 277–286 (2013).

Reda, F. M. et al. Dietary supplementation of potassium sorbate, hydrated sodium calcium almuniosilicate and methionine enhances growth, antioxidant status and immunity in growing rabbits exposed to aflatoxin B1 in the diet. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 104(1), 196–203 (2020).

Shen, H.-M., Ong, C.-N. & Shi, C.-Y. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in aflatoxin B1-induced cell injury in cultured rat hepatocytes. Toxicology 99(1–2), 115–123 (1995).

Da Silva, E., Bracarense, A. & Oswald, I. P. Mycotoxins and oxidative stress: Where are we?. World Mycotoxin J. 11(1), 113–134 (2018).

Dupré-Crochet, S., Erard, M. & Nüβe, O. ROS production in phagocytes: Why, when, and where?. J. Leukoc. Biol. 94(4), 657–670 (2013).

Juan, C. A., Pérez de la Lastra, J. M., Plou, F. J. & Pérez-Lebeña, E. The chemistry of reactive oxygen species (ROS) revisited: Outlining their role in biological macromolecules (DNA, lipids and proteins) and induced pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(9), 4642 (2021).

Mavrommatis, A. et al. Impact of mycotoxins on animals’ oxidative status. Antioxidants 10(2), 214 (2021).

Wang, J., Zhou, H., Wang, X., Mai, K. & He, G. Effects of silymarin on growth performance, antioxidant capacity and immune response in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus L.). J. World Aquac. Soc. 50(6), 1168–1181 (2019).

Fraschini, F., Demartini, G. & Esposti, D. Pharmacology of silymarin. Clin. Drug Investig. 22, 51–65 (2002).

Schubert, M. L. Gastric acid secretion. Curr. Opini. Gastroenterol. 32(6), 452–460 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the Agricultural Experiments and Researches Center, Benha University for their continued support this work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, T-A I.; methodology, T-A I., A.I-E, M.H-E., M.A-N., E.H–H.; software, T-A I., and E.H–H.; validation T-A I.; formal analysis, T-A I., A.I-E, M.H-E., M.A-N., and E.H–H.; investigation, T-A I., A.I-E, M.H-E., M.A-N., and E.H–H.; resources, T-A I., A.I-E, M.H-E., and E.H–H.; data curation, T-A I., A.I-E, M.H-E., M.A-N., and E.H–H., writing—original draft preparation, T-A I.; writing—review and editing, T-A I., A.I-E., M.A-N., E.H–H.; visualization T-A I.; supervision, T-A I.; and A.I-E.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Imbabi, T.A., El‐Sayed, A.I., El-Habbak, M.H. et al. Ameliorative effects of silymarin on aflatoxin B1 toxicity in weaned rabbits: impact on growth, blood profile, and oxidative stress. Sci Rep 14, 21666 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70623-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70623-z