Abstract

The pretreatment and saccharification of dewaxed bagasse (DWB) has been investigated under various reaction conditions ranging 2000 to 3200 psi, at 70 ± 1 °C in supercritical carbon dioxide (SCC). This has been in attempt to transform the DWB into fermentable sugar and bioethanol in high yields. The effect of SCC mediated pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis on structural and morphological alterations in DWB has been ascertained through diverse analytical methods. The sugar has been released through cellulase (40 FPU/mL) mediated enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated DWB in sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.7) within 1 h at SCC 2800 psi, 70 ± 1 °C. The released sugar was subsequently fermented in the presence of yeast (Saccharomyces crevices, 135 CFU) at 28 ± 1 °C over 72 h to afford the bioethanol. The SCC mediated process conducted in acetic acid:water media (1:1) at 2800 psi, 70 ± 1 °C over 6 h has afforded the pretreated DWB with maximum yield towards the production of fermentable sugar and bioethanol. The production of fermentable sugar and bioethanol has been electrochemically estimated through cyclic voltammetry (CV) and square wave voltammetry (SWV) over glassy carbon electrode in KOH (0.1 M). The electrochemical methods were found selective and in close agreement for estimation of the yields (%) of fermentable sugars and bioethanol. The yield (%) of fermentable sugar estimated from CV and SWV were 80.10 ± 5.34 and 79.00 ± 5.09 respectively. Whereas the yield (%) of bioethanol estimated from CV and SWV were 81.30 ± 2.78% and 78.6 ± 1.25% respectively. Present investigation delivers a SCC mediated green and sustainable method of pretreatment of DWB to afford the enhanced saccharification, to produce bioethanol in high yields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Supercritical fluids, particularly supercritical carbon dioxide (SCC) have received growing attention over decades for physicochemical pretreatment and saccharification of a broad range of agricultural and forest residues1. The ease of abundance, non-flammable, and non-toxic nature of CO2 makes it a leading source of production of cost effective SCC2,3. Pressure tunable density, diffusivity, solvating properties and low surface tension allow SCC for selective swelling and dissolution of macromolecular constituents with simultaneous enhancement of the surface area and porosity of biomass. SCC is conveniently generated by pressurizing the carbon dioxide at 1070.38 psi and 31.10 °C4. SCC has 102 to 103 time greater densities over traditional organic solvents, 10 to 102 times reduced viscosities over gases and high diffusion rate of 10−3 to 10−4 cm2/s times over liquids. The supercritically enhanced porosity and surface area facilitates the infusion of enzymes into pretreated biomass to deliver the fermentable sugar in high yields5,6.

SCB is an inexpensive, prominently abundant and energy rich fibrous byproduct disposed by sugar industries7,8. SCB is the biocomposites of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and waxes. SCB is widely used for preparation of biofuel, pulp, paper, biodegradable composite materials, bioethanol and other chemicals9. SCB with free wax content (by 4 to 15 wt%) referred as dewaxed bagasse (DWB)10 and has been utilized to achieve the fermentable sugar to produce bioethanol in high yields11. The isolated wax has been used in production of cosmetics and pharmaceutical10.

Brazil and the United States share approximately 80% of the production of bioethanol from SCB through traditional methods12. Production of bioethanol from agricultural and forest residues suffers from a series of constraints involving lignin shielding, matrix heterogeneity, wax content, high crystallinity of cellulose and low surface accessibility13. For such reasons, biomass has been subjected to stringent pretreatment through either the physical, chemical, physiochemical, and biochemical processes. A series of physical pretreatment processes based on milling14, microwave15, ultrasound techniques16 and pyrolysis17 predominantly reduce the particle size and crystallinity of biomass, however, demonstrates limited selectivity and produce inhibitory compounds13,18. Chemical pretreatment processes are employed to remove the hemicellulose and lignin from biomass19. Biochemical processes involve biodegradation of biomass by enzymes and microorganisms. The combination of two or more processes results in an enhanced yield of fermentable sugar, leading to production of bioethanol in high yields13.

Physicochemical pretreatment process involving SCC is relatively rapid, environmentally friendly and allows efficient conversion of biomass into fermentable sugars along with production of wax as byproduct. Physiochemical pretreatment process allows the rapid fragmentation of the complex macromolecular structure of biomass in the vicinity of enzymes or acidic media to afford the sugar enriched solutions which has been fermented into high yield of bioethanol20. The recovery of fermentable sugar solutions is however governed with quantitative loadings of DWB, enzyme, duration of exposure of SCC, operating temperature and pressure7,8. SCC mediated processes involving pretreatment of DWB followed by enzyme hydrolysis allow ease of separation of the fermentable sugar solution through depressurizing the reactor system at ambient conditions3.

The SCC mediated physiochemical pretreatment of SCB has been exclusively investigated in aqueous medium at 2500–4000 psi, 40–400 °C over 19–120 min in SCC21,22,23,24. This has been performed to enhance the porosity and surface area to ease the enzymatic hydrolysis of SCB. Enzymatic hydrolysis of SCB at 1450–3625 psi, 40–80 °C over 30–120 min in SCC has afforded 53–60 wt% sugar22. A set of another study reveals SCC mediated pretreatment of SCB at 1015–3500 psi, 60–190 °C, 15 min to 24 h followed by enzyme hydrolysis under ambient environment has afforded 11–79.2 wt% sugar20,25,26,27,28,29,30. Literature reveals that the recovery (wt%) of sugar through various pretreatment methods of SCB follows the order as: ultrasound (20.2%), 1.0% H2O2 (22.9%), SCC (61.3%), SCC in combination with ultrasound (65.8%) and maxium in SCC admixed with 1.0% H2O2 (97.8%)25. All the SCC mediated processes were commonly conducted at 187 °C, 2260 psi over 40 min25. Recently, the effect of acids on SCC mediated pretreatment of biomass has been investigated in attempt to afford the enhanced recovery of sugar8,31. The pretreatment of SCB in dilute H2SO4 (0.5%, v/v) in ambient environment, followed by enzymatic hydrolysis in SCC at 4350 psi, 40 °C over 180 min has produced 73.63 wt% sugar8. However, the pretreatment of wheat straw in SCC supplemented with acetic acid:water (1:1, v/v) system at 2500 psi and 180 °C over 45 min has afforded 74 wt% fermentable sugar31.

The present investigation deals with development of SCC mediated two-step process of production of bioethanol from DWB in high yields. The first step has been conducted through pretreatment of DWB in SCC in neutral30,32 and acidic conditions8. The second step involves a novel method based on SCC mediated saccharification of supercritically pretreated DWB in the vicinity of cellulase enzyme to afford the sugar with enhanced yield. In order to achieve the comparable results, the steps of pretreatment and enzyme hydrolysis were conducted at common temperature and pressure. The fermentable sugar solutions were isolated and subsequently incubated in media supplemented with yeast culture to afford the bioethanol. Electroanalytical methods based on cyclic voltammetry (CV) and square wave voltammetry (SWV) have been extensively studied for detection and quantification of isolated sugar33. In the aforesaid context, to the best literature survey, the availability of reports on electrochemical quantification of supercritically produced bioethanol through CV and SWV has been scanty. The electroanalytical methods employed in the present investigation have proven their enhanced reproducibility and sensitivity for detection of sugar and bioethanol over the usual chromatographic techniques33,34,35,36,37.

Materials and methods

Materials

All the chemicals and solvents (purity > 99.8%) were procured from Sd. Fine Chemicals India and used without further purifications. The solution of acetic acid in water was prepared through dissolution of glacial acetic acid (d = 1.05 g/cm3, purity 99.5%) into deionized water in equal volume ratio (1:1, v/v). Cellulase (40 FPU/mL) was procured from Biovencer HealthCare Pvt. Ltd, India. Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) was procured from Istore Direct Trading Private Limited India. SCB (Saccharum barberi) collected from the nearby sugar industry was washed with water and dried at 50 ± 1 °C/80 mmHg over 24 h (moisture content; 4.72 wt%). The dried SCB was pulverized into 80 mesh size and stored in a vacuum oven at 25 ± 1 °C/400 mmHg. SCB was dewaxed following the procedure recommended by ASTM D 1107 56 1972. Briefly, the wax content associated with pulverized SCB (10 g) was extracted into ethanol:benzene medium (1:2, 300 mL) in a Pyrex glass make soxlet extractor (500 mL) over 8 h. The residual biomass was isolated from the extractor and dried at 75 ± 1 °C over 48 h to afford the DWB with 90.4 wt% yields (Fig. 1). DNS reagent was prepared from 3,5-dinitro salicylic acid according to reported procedure38.

Cellulase activity

Cellulase activity in FPU was evaluated by embedding the filter paper (1 × 6 cm, ~ 50 mg) into a solution (5 mL) comprising sodium acetate buffer solutions (0.1 M, pH 4.7) supplemented at selected concentrations (0.1, 0.2 and 0.5 mL) of cellulase enzyme. The contents were incubated at 50 ± 1 °C over 60 min thereafter the enzymatic reaction was arrested through the addition of DNS reagent (3 mL) followed by heating over a boiling water bath for 5 min39. The formation of glucose was ascertained through appearance of dark brown coloration. The reaction mixture was diluted with 5 mL of H2O and the absorbance of all samples were measured at 540 nm. Cellulase activity was calculated according to the relation: FPU (unit/mL) = 0.37/C. where C = cellulase concentration to release 2.0 mg glucose (C = 1/Dilution).

SCC mediated pretreatment of DWB

SCC mediated pretreatment of DWB has been conducted in a high pressure reactor equipped with a reaction vessel (100 mL) connected to pressure gauge, feed and an exhaust valves. The vessel of reactor (Fig. 2a) was connected to a temperature controller (± 1 °C) and a chiller (5.0 ± 1 °C). The reactor vessel was charged with a suspension of DWB (2.0 g) into either of deionized water or acetic acid in water (1:1, v/v). The requisite mass of carbon dioxide was charged into the reactor at 5 ± 1 °C and the temperature of vessel was raised to 70 ± 1 °C to afford the supercritical pressure ranging from 2000 to 3200 psi (Table S1). The pretreatment process of DWB has been conducted under stable conditions in SCC over 3 h in SCC. During pretreatment process, the biomass remains in equilibrium with SCC. After 3 h of pretreatment, the temperature of the vessel was reduced to 25 ± 1 °C through chilling at 10 ± 1 °C. The reaction system was depressurized with fall in pressure at 10 psi/min. The gas like diffusivity and liquid like density allows SCC to infuse into the voids of the DWB (Fig. 2b)40. In event of depressurization, the SCC expands into the voids, which leads fragmentation of the biopolymer components associated with DWB. The pretreatment procedure conducted at 2800 psi, 70 ± 1 °C over 6 h has afforded the DWB accessible to saccharification to afford the DWB accessible to saccharification (Fig. 2c).

SCC mediated saccharification

The SCC mediated saccharification of DWB was conducted in the reactor system with an identical configuration as employed in SCC mediated pretreatment. The reactor vessel was charged with pretreated DWB (2.0 g), sodium acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.7, 50 mL) supplemented with cellulase enzyme (40 FPU/mL) and pressurized in SCC at 70 ± 1 °C, 2800 psi over 1 h (Fig. 3a). The sugar was liberated through hydrolysis of DWB followed by incubation under stirring at 150 rpm, 40 ± 1 °C over 24 h (Fig. 2b) and centrifugation at 10,000 rpm over 10 min (Fig. 3c)41.

Production of bioethanol

Bioethanol was prepared through fermentation of isolated sugar in yeast culture. For this purpose, the yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) was prepared by dissolving the yeast extract (5 g/L), agar (20 g/L), glucose (20 g/L) and peptone (10 g/L) in deionized water. Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 1 g) was serially diluted by 10−1 to 10−10 and inoculated (10−4 dilution, 1 mL) through pour plating followed by culturing on YPD broth and incubation at 28 ± 1 °C, 100 rpm for 72 h.

Visible colonies (135 CFU) appeared on the cultured media plate within 1 week. The pure culture was isolated through selection of a single colony followed by streaking onto solid yeast culture media. Inoculation was done by adding a loopful of yeast cells in a 10 mL liquid culture medium. The yeast cell concentration (106 cells m/L) in the medium was quantified at 600 nm. The morphology of yeast cells was confirmed at 100X magnification (Fig. S1). Sugar solution (50 mL) isolated after SCC mediated enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated DWB was subjected to fermentation in the presence of mature yeast cells (25 mL) at 100 rpm in media (250 mL, pH 4.8, Table S2) at 28 ± 1 °C over 72 h (Fig. 4). The bioethanol produced was isolated from culture media through distillation and was quantified through electroanalytical methods42.

Characterization

FTIR spectra were recorded over the Perkin Elmer spectrophotometer in KBr under transmission mode. Prior to microscopic examinations, all specimens were dried at 25 ± 1 °C and coated with gold43. SEM images were recorded over JEOL, JSM-6610 LV. Simultaneous thermogravimetric-differential thermal analysis-differential thermogravimetry (TG-DTA-DTG) was conducted at the rate of 10 °C/min in nitrogen over EXSTAR TG/ DTA 6300 with reference to alumina at a sample size of 5 ± 0.01 mg44. CV and SWV were conducted on IVIUM Potentiostat–Galvanostat using a triple electrode cell assembly equipped with a glassy carbon electrode (GCE), platinum wire as the counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode at room temperature45. All electrochemical observations were made five times and obtained data has been expressed with relative standard deviation (RSD) and standard errors (Table 1).

Results and discussion

FTIR analysis

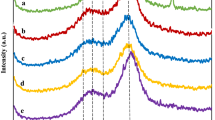

FTIR spectra of SCB (a) and DWB (b) and pretreated DWB (c) are presented in Fig. 5. SCB and DWB renders common wave numbers (cm−1) corresponding to νO–H at 3400–3499, containing intramolecular hydrogen bonding among the macromolecular segments in cellulose46. The common wave number at 899 cm−1 is attributes to the β-glycosidic linkage of cellulose associated with SCB and DWB47,48. The wave numbers at 2850–2970 (νC–H) of CH2, 1730 (νC=O) attributes to the acetyl and ester linkages associated with lignin, hemicellulose and pectin49,50.

Wave numbers at 1620–1649, 1512, 1595 and 1250 are respectively attributed to aromatic rings associated with lignin49 (Table S3). The increase in % transmittance is attributed to the infusion of CO2 leading to a reduction in the binding between lignin and macromolecular segment of DWB matrix21.

Thermal stability

The effect of removal of wax (9.6 wt%) on thermal stability of DWB has been investigated with reference to SCB through simultaneous TG-DTA-DTG in nitrogen environment (Fig. 6a,b). TG, DTA and DTG sequentially attribute to temperature dependent weight residue (%Wr), rate of degradation (mg/min) during the process of thermal decomposition.

The weight loss in TG at 100 °C attributes to moisture content (%, w/w) associated with biomass. SCB and DWB were decomposed in a single step with common TGo (200 °C), t½ (31 min) and DTA peak temperature (354 °C). Thermograms provides remarkable differences in the relative intensities (μv) and DTA signal, DTG peak temperature (°C) and production of char residue (wt%) of SCB (Fig. 6a) over DWB (Fig. 6b). SCB has shown an intense DTA signal (2.5 µV) over DWB (1.93 µV). Beyond the TGe, the decomposition of SCB and DWB has steadily progressed till 1000 °C, leaving char residues by 17.5 and 16.2 wt% respectively. The DTG (mg/min) for SCB (1.058) and DWB (1.034) progressed with respective peak temperatures at 328 and 357 °C. The shift in DTG peak temperature from 328 to 357 °C attribute to characteristic enhancement in thermal stability of DWB over SCB51.

Microstructure

Figure 7 demonstrates the SEM of DWB, pretreated DWB, and enzymatically hydrolyzed DWB respectively. To have comparative results, all the SEM images were recorded at 20 μm and 700X magnification. DWB reveals fibrous structures with soft, fragile pith cells wrapped over parallel aligned vascular bundles48. The effective pretreatment of DWB has been ensured over 3 h SCC at 2800 psi and 70 ± 1 °C (Fig. 7a)8. SCC mediated pretreatment over DWB reveals medullar pith separated from fibrous vascular bundles (Fig. 7b). The enzymatic hydrolysis in SCC over 1 h under identical temperature and pressure was revealed through the appearance of parenchymatous pith with the disappearance of fibrous vascular bundles in pretreated DWB due to saccharification (Fig. 7c). SEM is attributed to morphological changes in DWB during pretreatment and onward enzymatic hydrolysis. This has been revealed through the emergence of clearly visible vascular bundles with qualitative enhancement in the surface roughness of DWB52.

Electroanalysis

Electrochemical behavior of standard and isolated sugars derived from SCB (Fig. S2) and DWB was examined at 50 mV s−1 through CV in the potential window of − 1.3 to 1.3 V over GCE in KCl (0.1 M). CV of standard and isolated sugars from DWB pretreated in water and acetic acid:water media (1:1, v/v) showed reversible redox behavior with characteristic peaks at − 0.75 V and 0.25 V respectively (Fig. 8)34,53. Sugar isolated from acetic acid/water medium reflected better CV response over sugar isolated from DWB pretreatment in water medium. However, the electrochemical response of the sugar isolated from SCB was relatively inferior over DWB. Moreover, for 100 mL of the reactor vessel volume the permissible amount of biomass was found as 10 g to rendered the detectible scarification through analytical methods. The biomass charge into the reactor below 10 g have rendered the saccharification leading to low sugar yields to the detected via electroanalysis. Figure 9a demonstrates the continuous rise in peak current with successive addition of the standard sugar solution ranging from 0.12 mg/mL to 1.2 mg/mL. The pertinent calibration plot reveals peak current relation with sugar concentration as I = 0.0057c + 0.0048 at − 0.75 V (R2 = 0.9956) (Fig. 9b). The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) for CV and SWV estimation of all sugars and ethanol were calculated using the equations, LOD = 3Sd/m, and LOQ = 10Sd/m, where Sd is the standard deviation of ten responses of the blank solution and m is the slope of the regression line at signal/noise = 354. Linear relation obtained from calibration regression line of sugar gave LOD as 1.72 mg/mL and LOQ as 5.21 mg/mL.

Electrochemical behavior of standard ethanol and synthesized bioethanol from different pretreatment methods was examined by CV at 75 mV s−1 in the potential window of − 1.0 V to 1.0 V in NaOH (0.1 M) over GCE. CV of ethanol and synthesized bioethanol exhibited a pair of quasi-reversible couple peaks, indicative of characteristic oxidation and reduction at − 0.17 V and − 0.38 V, respectively55. CV reveals that bioethanol synthesized from acetic acid/water pretreated DWB showed high peak currents and better response over bioethanol extracted from water pretreated DWB (Fig. 10).

Figure 11a illustrates the variation in current with potential across successive additions of standard ethanol concentrations ranging from 5.23 mg/mL to 49.33 mg/mL. The calibration curve, generated by correlating peak current with ethanol concentration, exhibited a linear relationship expressed as I = 0.0023c + 0.135 at − 0.25 V (R2 = 0.9951) with LOD and LOQ calculated as 7.98 and 2.20 mg/mL respectively (Fig. 11b).

SWV was utilized for sensitive and rapid quantitative assessment of redox species in solution56,57. In the present investigation, the SWV of standard and isolated sugar solutions were performed at optimized pulse amplitude, step potential and frequency of 2 mV, 9 mV and 25 Hz, respectively in KCl (0.1 M) over GCE. The characteristics peak revealed by the standard and isolated sugars solutions in SWV at ~ − 0.75 V was used for quantification of sugars58. Figure 12a reveals the increase in the peak current with a concentration of aliquot of standard sugar added from 0.12 to 1.20 mg/mL in KCl (0.1 M). Peak current and concentration analysis reveals a linear increase following the relation I = 0.0057 c + 0.0048 (R2 = 0.9956) (Fig. 11b). These results gave excellent selectivity and repeatability for sugar estimation with LOD and LOQ as 0.172 ± 0.02 and 0.522 ± 0.05 mg/mL respectively.

The SWV of standard ethanol and bioethanol produced from fermentable sugar derived through supercritical saccharification of DWB were conducted under optimized conditions at pulse amplitude of 180 mV, step potential of 10 mV, and frequency of 50 Hz in NaOH (0.1 M) at GCE. SWV of standard and synthesized bioethanol reveals a common peak current at ~ 1.35 V, therefore was used for quantification of bioethanol59,60. Figure 13a depicts the linear progress in peak current with successive addition of standard ethanol in the range 5.23–49.33 mg/mL. Figure 12b illustrates the correlation between peak current and ethanol concentration, as depicted by the equation: I = 0.0121c + 0.9593 (R2 = 0.9933). This equation signifies the linear relationship observed between the peak current (I) and the ethanol concentration (c), indicating a strong correlation with high coefficient of determination (R2). These results gave excellent selectivity and repeatability for synthesized bioethanol estimation with LOD and LOQ as 9.27 ± 0.03 and 28.12 ± 0.05 mg/mL respectively.

Quantification of sugar and bioethanol

The calibration curves derived from CV (Figs. 9b and 11b) and SWV (Figs. 12b and 13b) were used for quantification of supercritically produced sugar and bioethanol from pretreated DWB. For this purpose, 300 µL of the sugar samples (from water and acetic acid/water pretreated DWB) were added in KCl (0.1 M) and bioethanol in NaOH (0.1 M) respectively for electroanalysis. Five consecutive CV and SWV measurements were run for isolated samples under identical conditions that were optimized for the electroanalysis of standard sugar and ethanol. The isolated sugars and bioethanol reflected redox behavior like their standard samples in CV. Percentage of recovery of sugar and ethanol were estimated from calibration curves derived from the measurements of standard concentrations and corresponding peak currents of CV and SWV measurements. Peak currents recorded at − 0.75 V and − 0.25 V for isolated sugar and bioethanol respectively were used to calculate the concentration by fitting in their calibration curves and presented in Table 1 (Figs. 9b and 11b). Furthermore, SWV derived calibration graphs (Figs. 12b and 13b) were used to quantify isolated sugar and bioethanol accurately from peak currents recorded at potential − 0.75 V and 1.35 V respectively (Table 1). The relative standard deviation and standard errors obtained from the analysis of five experiments under similar conditions was suggesting good precision in the measurements.

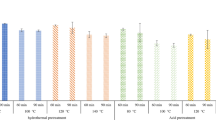

Electrochemical measurements demonstrate précised and reproducible quantification of fermentable sugar (71.00 ± 3.15% from CV; 65.9 ± 5.13% from SWV) and bioethanol (75.50 ± 2.32% from CV; 73.4 ± 1.01% from SWV) obtained through supercritical pretreatment of DWB in water medium. In contrast, electrochemical results highlight an improved yield of sugar (80.10 ± 5.34% from CV; 79.0 ± 5.09% from SWV) and bioethanol (81.30 ± 2.78% from CV; 78.6 ± 1.25% from SWV) from supercritically pretreated DWB in acetic acid:water (1:1, v/v) medium. The electroanalytical data reveals that the presence of acetic acid:water medium (1:1, v/v) has rendered the enhanced production of fermentable sugar and bioethanol over pure water medium. These findings reveal the potential of employing SCC mediated pretreatment of DWB in acetic acid/water media as a promising method for advancements in sustainable bioethanol production.

Results reveals that, due to unique pressure tunable physical properties of SCC it allow penetration and diffusion at molecular level to swell the biomass. Presence of aqueous acidic media in SCC catalyzes the process of hydrolysis of hemicellulose which leads to the effective dissolution of biomass and the process of depressurization through rapid expansion of SCC renders fragmentation of biomass. For such reasons, SCC mediated pretreatments processes relatively outperform over explosion methods involving steam61,62, organosolv63,64,65, liquid hot water (LHW)66 and ammonia fibre67,68, in terms of high biomass loading, low cost and operational conditions (Table 2).

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates the enhanced yield of fermentable sugar (80.10 ± 5.34%) and bioethanol (81.30 ± 2.78%) through pretreatment of DWB in acetic acid:water (1:1; v/v). The process of pretreatment and saccharification of DWB has been conducted at 2800 psi and 70 ± 1 °C in SCC. The electroanalytical methods reveal that pretreatment of DWB in acetic acid:water (1:1, v/v) relative to water medium was pivotal towards enhancements in the yield of fermentable sugar (14.14%) and bioethanol (20.92%). The prominence of saccharification by DWB was revealed by SEM through disappearance of fibrous vascular bundles in pretreated DWB.

In conclusion, the present study successfully demonstrates the potential of SCC as a green and sustainable medium for scalable and cost-effective conversion of biomass into fermentable sugar to produce the bioethanol in high yields. The process could further be scale up for SCC mediated transformation of the bulk quantity of the cellulose enriched biomasses into fermentable sugar and bioethanol. The developed process is economical and industrially viabile due to inexpensive nature of carbon dioxide associated with ease of transformation into SCC. The recycling of carbon dioxide along with isolation of product from reaction media has been facilitated at ambient conditions with reduced environmental impact. The findings may support the development of DWB based bio refineries for low-cost production of bioethanol.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Kumar, A., Kumar, V. & Singh, B. Cellulosic and hemicellulosic fractions of sugarcane bagasse: Potential, challenges and future perspective. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 169, 564–582 (2021).

Khalati, E., Oinas, P. & Favén, L. Techno-economic and safety assessment of supercritical CO2 extraction of essential oils and extracts. J. CO2 Util. 74, 102547 (2023).

Sharma, S., Mehtab, S. & Zaidi, M. G. H. Supercritical processing of thermally stable multiwalled carbon nanotube/boron nitride nanohybrids with synergistically improved electrical conductivity. Mater. Chem. Phys. 296, 127278 (2023).

Joshi, P., Bisht, G., Mehtab, S. & Zaidi, M. G. H. Supercritical synthesis and studies on non-isothermal kinetics and thermodynamics of solid state decomposition of nanoferrogels. Mater. Today Proc. 62, 6814–6818 (2022).

Tan, J. et al. Advances in pretreatment of straw biomass for sugar production. Front. Chem. 9, 696030 (2021).

New, E. K. et al. The application of green solvent in a biorefinery using lignocellulosic biomass as a feedstock. J. Environ. Manag. 307, 114385 (2022).

Sharma, B., Larroche, C. & Dussap, C. G. Comprehensive assessment of 2G bioethanol production. Biores. Technol. 313, 123630 (2020).

de Carvalho Silvello, M. A., Martínez, J. & Goldbeck, R. Application of supercritical CO2 treatment enhances enzymatic hydrolysis of sugarcane bagasse. BioEnergy Res. 13, 786–796 (2020).

Konde, K. S., Nagarajan, S., Kumar, V., Patil, S. V. & Ranade, V. V. Sugarcane bagasse based biorefineries in India: Potential and challenges. Sustain. Energy Fuels 5, 52–78 (2021).

Qi, G. et al. Extraction and characterization of wax from sugarcane bagasse and the enzymatic hydrolysis of dewaxed sugarcane bagasse. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 47, 276–281 (2017).

Rostagno, M. A. et al. Subcritical and supercritical technology for the production of second generation bioethanol. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 35, 302–312 (2015).

Nikolic, S., Pejin, J. & Mojovic, L. Challenges in bioethanol production: Utilization of cotton fabrics as a feedstock. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 22, 375–390 (2016).

Escobar, E. L. N., Da Silva, T. A., Pirich, C. L., Corazza, M. L. & Pereira Ramos, L. Supercritical fluids: A promising technique for biomass pretreatment and fractionation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 252 (2020).

Sitotaw, Y. W., Habtu, N. G., Gebreyohannes, A. Y., Nunes, S. P. & Van Gerven, T. Ball milling as an important pretreatment technique in lignocellulose biorefineries: A review. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 13, 15593–15616 (2023).

Li, H., Qu, Y., Yang, Y., Chang, S. & Xu, J. Microwave irradiation—A green and efficient way to pretreat biomass. Biores. Technol. 199, 34–41 (2016).

Ziaei-Rad, Z. et al. Investigation of a robust pretreatment technique based on ultrasound-assisted, cost-effective ionic liquid for enhancing saccharification and bioethanol production from wheat straw. Sci. Rep. 13, 446 (2023).

Kumar, R. et al. Lignocellulose biomass pyrolysis for bio-oil production: A review of biomass pre-treatment methods for production of drop-in fuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 123, 109763 (2020).

Ahorsu, R., Medina, F. & Constanti, M. Significance and challenges of biomass as a suitable feedstock for bioenergy and biochemical production: A review. Energies 11, 3366 (2018).

Thite, V. S. & Nerurkar, A. S. Valorization of sugarcane bagasse by chemical pretreatment and enzyme mediated deconstruction. Sci. Rep. 9, 15904 (2019).

Zhang, Q., Zhao, M., Xu, Q., Ren, H. & Yin, J. Enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis of sorghum stalk by supercritical carbon dioxide and ultrasonic pretreatment. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 188, 101–111 (2019).

Srinivasan, N. & Ju, L. K. Pretreatment of guayule biomass using supercritical carbon dioxide-based method. Biores. Technol. 101, 9785–9791 (2010).

Benazzi, T. et al. Pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse using supercritical carbon dioxide combined with ultrasound to improve the enzymatic hydrolysis. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 52, 247–250 (2013).

Gu, T., Held, M. A. & Faik, A. Supercritical CO2 and ionic liquids for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass in bioethanol production. Environ. Technol. 34, 1735–1749 (2013).

Serna, L. D., Alzate, C. O. & Alzate, C. C. Supercritical fluids as a green technology for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Biores. Technol. 199, 113–120 (2016).

Phan, D. T. & Tan, C. S. Innovative pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse using supercritical CO2 followed by alkaline hydrogen peroxide. Biores. Technol. 167, 192–197 (2014).

Pasquini, D., Pimenta, M. T. B., Ferreira, L. H. & da Silva Curvelo, A. A. Extraction of lignin from sugar cane bagasse and Pinus taeda wood chips using ethanol–water mixtures and carbon dioxide at high pressures. J. Supercrit. Fluids 36, 31–39 (2005).

Alinia, R., Zabihi, S., Esmaeilzadeh, F. & Kalajahi, J. F. Pretreatment of wheat straw by supercritical CO2 and its enzymatic hydrolysis for sugar production. Biosyst. Eng. 107, 61–66 (2010).

Narayanaswamy, N., Faik, A., Goetz, D. J. & Gu, T. Supercritical carbon dioxide pretreatment of corn stover and switchgrass for lignocellulosic ethanol production. Biores. Technol. 102, 6995–7000 (2011).

Oliveira, T. C. G. et al. Subcritical water hydrolysis pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse to produce second generation ethanol. J. Supercrit. Fluids 164, 104916 (2020).

Zhang, H. & Wu, S. Enhanced enzymatic cellulose hydrolysis by subcritical carbon dioxide pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse. Biores. Technol. 158, 161–165 (2014).

Zabihi, S., Sharafi, A., Motamedi, H., Esmaeilzadeh, F. & Doherty, W. O. Environmentally friendly acetic acid/steam explosion/supercritical carbon dioxide system for the pre-treatment of wheat straw. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 37867–37881 (2021).

Gundupalli, M. P., Cheng, Y. S., Chuetor, S., Bhattacharyya, D. & Sriariyanun, M. Effect of dewaxing on saccharification and ethanol production from different lignocellulosic biomass. Biores. Technol. 339, 125596 (2021).

Santos, F. C. U., Paim, L. L., da Silva, J. L. & Stradiotto, N. R. Electrochemical determination of total reducing sugars from bioethanol production using glassy carbon electrode modified with graphene oxide containing copper nanoparticles. Fuel 163, 112–121 (2016).

Cardoso de Sa, A., Cipri, A., Gonzalez-Calabuig, A., Stradiotto, N. R. & del Valle, M. Multivariate determination of total sugar content and ethanol in bioethanol production using carbon electrodes modified with MWCNT/MeOOH and chemometric data treatment. Electroanalysis 30, 1696–1705 (2018).

Tiscione, N. B., Alford, I., Yeatman, D. T. & Shan, X. Ethanol analysis by headspace gas chromatography with simultaneous flame-ionization and mass spectrometry detection. J. Anal. Toxicol. 35, 501–511 (2011).

De Sa, L. R. V., de Oliveira Moutta, R., da Silva Bon, E. P., Cammarota, M. C. & Ferreira-Leitao, V. S. Fermentative biohydrogen production using hemicellulose fractions: Analytical validation for C5 and C6-sugars, acids and inhibitors by HPLC. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 40, 13888–13900 (2015).

Nisha, M. et al. Direct estimation of ethanol as a negative peak from alcoholic beverages and fermentation broths by reversed phase-HPLC. Anal. Methods 8, 4762–4770 (2016).

Yang, H. J., Lee, Y. S. & Choi, I. S. Comparison of physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of fermented soybean-based red pepper paste, Gochujang, prepared with five different red pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) varieties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 55, 792–801 (2018).

Yu, X. et al. Measurement of filter paper activities of cellulase with microplate-based assay. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 23, S93–S98 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. Role of supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO2) in fabrication of inorganic-based materials: A green and unique route. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 22, 695–717 (2021).

Shao, Q. et al. Enzymatic digestibility and ethanol fermentability of AFEX-treated starch-rich lignocellulosics such as corn silage and whole corn plant. Biotechnol. Biofuels 3, 1–10 (2010).

Tgarguifa, A., Abderafi, S. & Bounahmidi, T. Modeling and optimization of distillation to produce bioethanol. Energy Procedia 139, 43–48 (2017).

Mohanakannan, S., Balaji, A. & Swaminathan, J. Investigation of mechanical, thermal, and chemical properties of raw and NaOH-treated bagasse/halfa grass/coir fiber. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 1–10 (2024).

Shah, M. A., Khan, M. N. S. & Kumar, V. Biomass residue characterization for their potential application as biofuels. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 134, 2137–2145 (2018).

Mohammad, F., Arfin, T. & Al-lohedan, H. A. Enhanced biosorption and electrochemical performance of sugarcane bagasse derived a polylactic acid-graphene oxide-CeO2 composite. Mater. Chem. Phys. 229, 117–123 (2019).

Hospodarova, V., Singovszka, E. & Stevulova, N. Characterization of cellulosic fibers by FTIR spectroscopy for their further implementation to building materials. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 9, 303–310 (2018).

Abderrahim, B. et al. Kinetic thermal degradation of cellulose, polybutylene succinate and a green composite: Comparative study. World J. Environ. Eng. 3, 95–110 (2015).

Kumar, A., Negi, Y. S., Choudhary, V. & Bhardwaj, N. K. Characterization of cellulose nanocrystals produced by acid-hydrolysis from sugarcane bagasse as agro-waste. J. Mater. Phys. Chem. 2, 1–8 (2014).

Rashid, T., Kait, C. F. & Murugesan, T. A “Fourier transformed infrared” compound study of lignin recovered from a formic acid process. Procedia Eng. 148, 1312–1319 (2016).

Javier-Astete, R., Jimenez-Davalos, J. & Zolla, G. Determination of hemicellulose, cellulose, holocellulose and lignin content using FTIR in Calycophyllumspruceanum (Benth.) K. Schum. and Guazumacrinita Lam. PLoS One 16, e0256559 (2021).

Natanim, D., Tesfaye, G., Anteneh, B. & Tsige, G. M. Preparation and characterization of cellulose and microcrystalline cellulose from sugarcane bagasse and assessment of the microcrystalline cellulose as a directly compressible excipient. Ethiop. Pharm. J. 36, 81–96 (2020).

Waghmare, P. R., Khandare, R. V., Jeon, B. H. & Govindwar, S. P. Enzymatic hydrolysis of biologically pretreated sorghum husk for bioethanol production. Biofuel Res. J. 5, 846–853 (2018).

Ward, R. A. et al. Electrochemical quantification of D-glucose during the production of bioethanol from thermo-mechanically pre-treated wheat straw. Electrochem. Commun. 124, 106942 (2021).

Guzinski, M., Lindner, E., Pendley, B. & Chaum, E. Electrochemical sensor for tricyclic antidepressants with low nanomolar detection limit: Quantitative determination of amitriptyline and nortriptyline in blood. Talanta 239, 123072 (2022).

Han, L., Ju, H. & Xu, Y. Ethanol electro-oxidation: Cyclic voltammetry, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and galvanostatic oscillation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 37, 15156–15163 (2012).

Mirceski, V. et al. Square-wave voltammetry: A review on the recent progress. Electroanalysis 25, 2411–2422 (2013).

Mehtab, S. et al. Electrochemical monitoring of congo red degradation using strontium titanate-doped biochar nanohybrids derived photocatalytic plates. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-28633-3 (2023).

Antigo Medeiros, R., de Carvalho, A. E., Rocha-Filho, R. C. & Fatibello-Filho, O. Square-wave voltammetry determination of aspartame in dietary products using a boron-doped diamond electrode. Anal. Lett. 40, 3195–3207 (2007).

Yu, J. J., Huang, W. & Hibbert, D. B. The determination of ethanol in wine by voltammetry with an internal standard. Electroanalysis 9, 544–548 (1997).

Donini, C. A., Silva, M. K., Bronzato, G. R., Leao, A. L. & Cesarino, I. Evaluation of a biosensor based on reduced graphene oxide and glucose oxidase enzyme on the monitoring of second-generation ethanol production. J. Solid State Electrochem. 24, 2011–2018 (2020).

Amores, I. et al. Ethanol production from sugarcane bagasse pretreated by steam explosion. Electron. J. Energy Environ. 1, 25–36 (2013).

Sendelius, J. Steam pretreatment optimisation for sugarcane bagasse in bioethanol production. Master of Science Thesis (Department of Chemical Engineering, Lund University, 2005).

Mesa, L. et al. The effect of organosolv pretreatment variables on enzymatic hydrolysis of sugarcane bagasse. Chem. Eng. J. 168, 1157–1162 (2011).

Terán Hilares, R. et al. Organosolv pretreatment of sugar cane bagasse for bioethanol production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56, 3833–3838 (2017).

Hermsdorff, G. B. et al. Ethanol organosolv pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse assisted by organic acids and supercritical carbon dioxide. Carbohydr. Polym. 300, 120263 (2023).

Yu, Q. et al. Pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse with liquid hot water and aqueous ammonia. Bioresour. Technol. 144, 210–215 (2013).

Biswas, R., Uellendahl, H. & Ahring, B. K. Wet explosion pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse for enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis. Biomass Bioenergy 61, 104–113 (2014).

Mokomele, T. et al. Ethanol production potential from AFEX™ and steam-exploded sugarcane residues for sugarcane biorefineries. Biotechnol. Biofuels 11, 1–21 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Research Grant No. ERIP/ER/0703649/M/01/1092 funded for generation of research facilities by Government of India acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mohammad Aziz: Data Curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing—original draft. Diksha Palariya: Data Curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing—original draft. Sameena Mehtab: Project administration, Data Curation, Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. M.G.H. Zaidi: Supervision, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. Yasser Vasseghian: Project administration, Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aziz, M., Palariya, D., Mehtab, S. et al. Enhanced production of bioethanol through supercritical carbon dioxide-mediated pretreatment and saccharification of dewaxed bagasse. Sci Rep 14, 21450 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70727-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70727-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ongoing progress on γ-irradiation technology for lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment in producing bioethanol

Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management (2025)