Abstract

A fractional model for the kinetics of hepatitis B transmission was developed. The hepatitis B virus significantly affects the world’s economic and health systems. Acute and chronic carrier phases play a crucial part in the spread of the HBV infection. The Hepatitis B infection can be spread by chronic carriers even though they show no symptoms. In this article, we looked into the Hepatitis B virus’s various stages of infection-related transmission and built a nonlinear epidemic. Then, a fractional hepatitis B virus model using a Caputo derivative and vaccine effects is created. First, we determined the proposed model’s essential reproductive value and equilibria. With the aid of Fixed Point Theory, a qualitative analysis of the problem’s approximative root has been produced. The Adams-Bashforth predictor-corrector scheme is used to aid in the iterative approximate technique’s evaluation of the fractional system under consideration that has the Caputo derivative. In the final section, a graphical representation compares various noninteger orders and displays the discovered scheme findings. In this study, we’ve utilized Artificial Neural Network (ANN) techniques to partition the dataset into three categories: training, testing, and validation. Our analysis delves deep into each category, comprehensively examining the dataset’s characteristics and behaviors within these divisions. The study comprehensively analyzes the fractional HBV transmission model, incorporating both mathematical and computational approaches. The findings contribute to a better understanding of the dynamics of HBV infection and can inform the development of effective public health interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a serious viral disease affecting millions worldwide. The virus also causes other illnesses related to human health, such as liver damage. Hepatitis B epidemiology proposes two human transmission routes, such as horizontal and vertical. Although vertical transmission occurs when a woman who has the virus passes it on to her kid, horizontal transmission involves sharing objects like razors, needles, and sexual intercourse. 2015 saw a significant increase in the number of HBV infections associated with liver infections and fatalities, and several nations throughout the world, including China, are still dealing with this problem.

More than 350 million people worldwide have chronic HBV bacterial infections1; these disorders have a 26–41% risk of developing fibrosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and severe liver diseases2. For this, HBV infection is a major global health concern. According to this information, a person infected with the HBV infection has a plasma weight of 2 × 1011 to 3 × 10123. Thus, a liver weighs 1.5 kg, nearly the same as the human body’s total number of liver cells. Because of its size, we can only employ the routine rate of occurrence in turn of the incidences for adequate pressure. HBV is directly produced after two or three days after therapy4. It is included in the article for no more than 7 to 13 months5.

It is now widely acknowledged that epidemiological formulations create conflicting effects, appropriately in the safety and management of viral disorders6,7,8. Complex mathematical models with various premises and characteristics are created by examining the literature to study various illnesses. Generally, the intensity of viruses in people’s viral, bacterial infections is affected by probabilistically disturbed components (such as moisture, rainfall, and heat dissipation on someone else). Moreover, we can probabilistically examine the idealized models using the same methodologies in the formal constructs. It is acknowledged that such actual models can also include the impact of changing environmental conditions. The oscillation of factors provided by the outside atmosphere or the sounds created by systems in the real world to make up factors affections9. The stochastic models with a probabilistic system will be close to precise results in the comparative and provide an increased layer of options. For detailed testing and a more extensive discussion of the literature on probabilistic representations of modeling interrupted by Zig-Zag phenomena, see10. Compared to predictable models for different processes, the outputs of probabilistic solutions are closer to those of big issues.

Because of the various options of orders of derivatives, fractional differential and integral equations that depict real-world occurrences are essential in studying nonlinear dynamics. The current calculus of fractional differentiation and integral has been shown to have numerous applications for various issues in a more exact and accurate style11. The conclusions drawn through noninteger order products are viewed to be highly accurate and have an extra bit of dynamics, especially with traditional models. This allows for exploring epidemiology and different ecological, social, physiological, and financial realities using worldwide fractional-order derivatives. Academics and scientists are more interested in studying the new notion of differentiation and integrals than they are in studying traditional derivatives. Specialists and mathematicians are attempting to focus on numerous sectors of noninteger order derivatives for outcomes due to the more actual results of present calculus. Various real-world issues, including modeling of viral infections and the fundamental Lotka-Volterra system, have been addressed using variable orders integral equations and derivative equations12,13. The modeling of noninteger order differential equations is covered in the research using a variety of approximation and exact techniques, including Predictor-Corrector, Adams-Bashforth, and other well-known approaches14,15. Numerous academics have developed mathematical models of COVID-19’s viscous flow; for instance, see16. Additionally, a wealth of data has been published on using current calculus for tuberculosis models, and numerous researchers have explored biology and physics issues due to FDEs17.

The study of infectious disease models has gained significant attention in recent years, with researchers exploring various mathematical frameworks to understand disease dynamics and inform public health interventions. In particular, the application of fractional-order derivatives has emerged as a promising approach to model complex epidemiological phenomena. Several studies have investigated fractional-order models for diseases such as toxoplasmosis18,19, HIV/AIDS20, tuberculosis21, pine wilt disease22,23, typhoid fever24, and malaria25. These models have demonstrated the ability to capture the non-integer order dynamics inherent in many biological systems. Additionally, researchers have explored the use of stochastic and discrete-time models to study disease propagation, accounting for the inherent randomness and heterogeneity in real-world scenarios26,27. Furthermore, the incorporation of advanced machine learning techniques, such as ensemble classifiers28, has shown potential in improving disease classification and prediction. The growing body of literature in this field highlights the multifaceted and interdisciplinary nature of epidemiological modeling, providing a strong foundation for the current study29. Fractional-order models have emerged as a promising approach for studying the complex dynamics of infectious diseases. Recent research has explored the application of these models to analyze diseases such as human papillomavirus30 and disease dynamics in prey-predator systems31. The incorporation of fractional calculus and fractal theory in these models has provided valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms and transmission patterns31. Continued advancement in this field is crucial for developing innovative techniques to better understand and manage infectious disease challenges.

Using the findings of the prior studies, we create a viral illness method for HBV utilizing the idea of the fractional operator by using a mild solution with the Vaccination class and Asymptomatic class in this article. To investigate the epidemic more thoroughly, we build the characteristics of HBV using Vaccinated and Asymptomatic class carriers, which have multiple elements for examining HBV dynamical behavior in the research. The authors of17 have investigated the HBV virus using a brand-new mathematical framework with an Asymptomatic class. Individuals with HBV infection may remain symptom-free for 31 to 181 days and spread the illness to others, which can result in death in human civilizations32,33. Our assessment attempts to develop a brand-new Hepatitis (HBV) model that includes vaccination and asymptomatic carriers based on the research on HBV modeling34. Initially, using the numerals of the Atangana-Baleanu fractional operator, a unique constructive derivative, the behavior of the dynamic system is produced in the context of integer or natural order derivatives and spreads to noninteger order derivatives. The main goal of this research project is to easily compare human health issues related to vaccination that cause a delay in the effective management of the HBV epidemic through mathematical models. We will finish developing effective vaccines to prevent illnesses from emerging in the actual world.

The document’s arrangement continues as follows: A brief overview of the spread of HBV and the contributions of well-known experts in this field are provided in the section under “Introduction.” Section “HBV mathematical model” presents the construction of the model mathematically as well as its fundamental features.The domestic and international stability of the stochastic model are presented in Section “Stability Analysis.” We reconstructed the model with fractional derivative in Section “Fractional order HBV model.” In the part under “Preliminaries,” we also include a few fundamental lemmas and definitions. The examination of the recommended fractional model’s solution is presented in the section under “Existence of Solution.” The suggested fractional model’s Hyers-Ulam stability is covered in Section “Hyers-Ulam stability.” We discussed the proposed model’s mathematical setup and visual outcomes in Section “Numerical Solutions.” The result of the work done in the paper is briefly covered in the section under “Conclusion.”

Model for the HBV virus

Vaccinations and time-delay inspections are price strategies for reducing the HBV viral sickness from the perspective of actual medical examinations. The World Health Organization correctly advised that effective HBV immunization must be used according to step-by-step criteria in areas with high infection rates. Several scientists have created stochastic HBV epidemic simulations using vaccination strategies as a result5. The model for the nonlinear occurrence of HBV transmission is given. The cases are split into five groups based on the features of HBV: the susceptible population S(t), the vaccination class V(t), the acute infectious class A(t), the chronic infection C(t), and the immunized R(t). \(N({t}) = S({t}) + V({t} + A({t}) + R({t}) + C({t})\) is the population density over all time t; see Fig. 1.

Furthermore, we presumed

- \(A_1\) ::

-

The variables and stochastic processes of the simulation are good.

- \(A_2\) ::

-

Because the duration of acute infection is relatively brief if treatment is unsuccessful, the infected individual will revert to the chronic compartment.

- \(A_3\) ::

-

We have excluded the mortality rate associated with HBV if liver histological has reduced due to therapy.

- \(A_4\) ::

-

An individual is considered susceptible forever once they have received a vaccination or been cured after treatment.

- \(A_5\) ::

-

The exterminated species possesses protection.

The situation under consideration is created and enhanced by Din et al.35. Numerous formulas of epidemic diseases with a prevalence rate of the Harmonic Mean type (HMTIR) have been researched in the literature36,37. Therefore, the paper examines a formulation used in epidemiology to describe the incidence of HBV in a society. We create the HMTIR between good health and acutely affected participants and between acutely infected and vaccinated people to determine which contagious patients go rapidly. The normality test of a data collection is measured as the average of the two numbers. The geometric mean is utilized for average ratios or frequencies by varying the provided data. Despite being considered, a harmonic mean performs less well for some massive quantities than geometric or arithmetic means. Occasionally, it is used when the variance of the parameters is substantial. The probability that the density will achieve habitat loss in a specific amount of time but far faster than other event ratios is known as the harmonic occurrences. Whenever a number determines a person’s value, the harmonic mean is a decent incidence frequency compared to similar units. The Harmonic incidence rate also has a genuine mean of the rates and fractions in various studies. It is susceptible to a single number that is below average. Depending on those above \((A 1-A 5)\) hypotheses and other associated constraints, the behaviors of HBV are described by the simulation tool:

Several practical issues, including epidemiological dynamical scenarios, demonstrate how dependent systems with global features are crucial to the validity of natural problems. Owing to fractional-order derivatives’ time-dependent kernels, systems with noninteger-order derivatives represent these problems well. The Caputo noninteger order derivative is the more generic of the various fractional operators described in the literature. The significance and benefit of using Caputo fractional-order derivatives is that they use begin assumptions comparable to modern differential calculus, i.e., they do not necessitate noninteger order initial assumptions14.

Motivated by38, our study’s goal is to examine a newly developed System 1 that uses noninteger order differentiation operators with a non-local and singular kernel since it produces more accurate outcomes than naturalistic orders11. We discover the existence of our model under consideration’s root using the fixed point theory notion. An arbitrary-orders operator system in the meaning of the suggested approach is examined:

We will investigate the model underlying initial conditions for \(\vartheta \in (1,2)\),

The governing equations are described in Table 1. The findings show that the medicines are not pure because they only partially cure illnesses. By doing so, those who have received vaccinations can contract illnesses after coming into contact with seriously ill people. It should be remembered that \(0< \tau _1 < 1(\tau _1 = 1)\) indicates a high vaccine, whereas \(\tau _1 = 0\) indicates a vaccine that provides no safety at any time.

In this part, we determine the figure’s viability, stability point, and fundamental biological value for 1 with the help of Table 1:

Region of invariant

We view all of the model’s variables as positive. Since there are real Humans in the environment, the state variables are believed to be favorable at time \(\upsilon = 0\). In the form of differential equations, the behaviors of the entire human population are as regards:

The system’s orientation equilibrium is

Consider the following biologically viable area \(\Delta \):

When equation 2 is resolved, we get

So

Because of this, the positively invariant domain is \(\Delta \), and the model is theoretically and epidemiologically bounded.

Reproduction number \(R_0\)

To compute the basic reproduction number for our system, we follow as38:

Let \(x = (A,C)\) is the infectious compartment, then it give from model 1 that:

Now, using the next generation matrix approach, we have the following:

where

The spectral radius \(R_0\) of the matrix is

and it is the required basic reproduction number \(R_0\) for the system 1.

Preliminaries

Below is a list of the results we can still recall.

Lemma 2.1

(Gronwall lemma)39 Assume \(\mu \) , \(y \in \mathcal {H} ([0,1],{\mathbb {R}}_+)\) and let \(\mu \) be increasing. If \(\mathfrak {u} \in \mathcal {H} ([0,1],{\mathbb {R}}_+)\) satisfies

then

Definition 2.1

[40] The fractional RL derivative is defined as

Definition 2.2

40] The Caputo fractional derivatives \(_a^\mathcal {C}{D}_\omega ^\alpha \chi (\omega )\) of order \(\alpha \in {\mathbb {R}}^+\) are defined by

in which \(k=[\alpha ]+1\).

Definition 2.3

41 The Wright function, \(\psi _{\alpha }\) is defined by

Lemma 2.2

42 Consider \(\{\mathcal {H}(\omega )\}_{\omega \in {\mathbb {R}}}\) as a strongly continuous cosine category in X fulfilling \(\Vert \mathcal {H}(\omega )\Vert _{L_{b}(X)} \le Me^{\Omega |\omega |}, \omega \in {\mathbb {R}}\), and \(\mathcal {A}\) as an infinitesimal generator of \(\{\mathcal {H}(\omega )\}_{\omega \in {\mathbb {R}}}\). Then for \(\textrm{Re}(\lambda ) > \omega \) and \(\lambda ^2 \in \rho (A)\),

Theorem 2.3

If X(t) fulfills (1) of equation (4) then Y(t) is given by

holds, then

\(\forall ~ {t} \in [0,b]\), such that

where \(C_q({t})\) and \(K_q({t})\) are continuous with \({K}(0) = I\) and \(C(0) = I\), \(|{C}_q({t})| \leqslant c, c > 1\) and \(|{{K}}_q({t})| \leqslant c, c > 1, ~ \forall ~ {t} \in [0,T]\).

Existence of solution

To consider the possibility that the presented problem has a solution, we first construct the mapping as regards:

The created problem can be expressed as presented using 7:

Using Theorem 2.3, equation 8 becomes

where

Using 9 and , defines two different operators F and G, by 9

Additionally, we assume that the parameters are satisfied:

\((D_1)\) If constant \(\beta _1\) and \(\beta _2\), fulfilled as given

\((D_2)\) If constant \(\kappa > 0 \forall Z, Z_1 \in X\), fulfilling as

Theorem 3.1

If \((D_1)\) and \((D_2)\) hold, therefore 9 must include their root, which implies that the root of the specified system 1 exists. Similarly, if

Proof

Consider \(Z_1 \in B\) as \(B = \{Z \in Y: \Vert Z\Vert \le r, r > 0\}\) is a near convex set to demonstrate that F is a contraction. Using the research of F as shown in 11, we obtain

F is a contraction.

We demonstrate that G has upper and lower bounds and must be continuous to deduce that G demonstrates relative compactness. To do this, we write as follows:

As long as \(\Theta \) is continuous, Mapping G acts constantly. As an afterthought for \(u \in B\), we put as

Therefore, 12 indicates that G has upper and lower bounds. Take the expression \({t}_1 > {t}_2 \in [0,\Im ]\) as

As \({t}_1 \rightarrow {t}_2\), result 15 finishes, also G is continuous so

Because G has upper and lower bounds and is continuous, it is also bounded, continuous, and uniformly continuous. G exhibits relative compactness and is entirely continuous, according to Arzela-Ascoli results. According to Theorem 3.1, problem 9, which is mentioned above, has a root. \(\square \)

For one root, we proceed as follows.

Theorem 3.2

Equation 9 has one root due to the requirement \((D_2)\), which suggests that the current proposal 1 has just one result.

Proof

Let define \(\Im : Y \rightarrow Y\) by

Let \(Z,Z_1 \in Y\), then

where

\(\Im \) is contracted from 17. The solution 9, therefore, only has one root. Simulation 1 has one zero as a result. \(\square \)

Hyers-Ulam stability

Definition 4.1

When \(\gamma \ge 0 \forall \epsilon > 0\), as well as any root \(Y \in C^1(G,R)\) of inequality are present, system 1 is Hyers-Ulam stable43:

there will be a distinct root for problem 1\(\Xi \in C^1(G,R)\) as

Definition 4.2

A fixed \(X_i > 0, i \in N^5\) trying to satisfy the following conditions is considered Hypers-Ulam stable for the Caputo fractional integration model described by equation 9. For every \(\gamma _i > 0, i \in N^5\), with

there exist \((\hat{S}({t}), \hat{V}({t}), \hat{A}({t}), \hat{C}({t}), \hat{J}({t}), \hat{R}({t}))\) which are fulfilling

Theorem 4.1

The proposed solution 1 is Hyers-Ulam stable under \(Y = C[0,\Im ]\).

Proof

Theorem 5 demonstrates that the given issue 1 has a single root (S(t), V(t), A(t), C(t), R(t)) that satisfies the system’s equation 9. Now comes

Taking, \(\gamma _i = \Omega _i, \Delta _i = \frac{1-\vartheta }{B(\vartheta )}+\frac{\vartheta }{B(\vartheta )\Gamma (\vartheta )}\), this implies

Thus, we get

The fractional model 1 is Hyers-Ulam stable because the issue 9 is Hyers-Ulam by equations 23 and 24. \(\square \)

Numerical solutions

In this part of the study, we will find the approximations to the model’s solutions 1. The popular Fractional Adam-Bashforth approach has been used to enumerate the noninteger order integration18. Using beginning assumptions and the operator \(I_0^\varrho \), we modify the noninteger order model 9 into fractional Volterra type integration equations:

We obtain for \({t} = {{t}}_{m+1}\):

By using the bi-step lagrange’s polynomial interpolate to approximate \(K_1\) to \(K_5\) in \([{t}_k,{t}_{k+1}]\) and re-inserting it into 25, we obtain

Upon combining it with the term in 26 and inserting it once more, we obtain

where

Discussions of numerical simulation

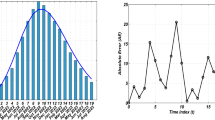

In this part, we use the approximate solution technique to demonstrate the evolving behaviors of the Caputo derivative generalized HBV illness issue 1. The initial approximations were S(0) = 1.45; V(0) = 1.154; A(0) = 1.125; C(0) = 1.105; and R(0) = 1.105. The parameters from 17 that we selected are shown in Table 2 and used in the numerical results. The timing scale is suggested to be 25 in the graphical numerical iterations. With the use of Matlab’s Adams-Bashforth Moulton iteration, the general fractional predictor-corrector method is used to create the graphical depiction. The agents are initially generated for a range of noninteger order values to understand the dynamics of the populations of the above agents based on their infection circumstances. Figs. 2-6 show the expatriation. In the numerical simulation procedures, the populations of Susceptible and Vaccinated people grow exponentially. A significant increase is observed in the population of those who have received vaccinations, whereas acute cases of chronic infection and recovery cases decrease. According to biological ideas, this effect results from lengthy immunization periods and a wealth of public knowledge. The graphical representation demonstrates that for the taken-in HBV system, the results of globalized operators appear to be more accurate. Figures 2-6 illustrate how the System 1 changes its behaviors when given different values of = 1.95, 1.85, 1.75, 1.65, and 1.55.

The model’s data set is divided into three categories: 70% for training, 15% for testing, and 15% for validation. Every category has a unique fractional order. Figure 3a represent the approach of ANN with Adam Bashforth method. Figure 3b illustrates the performance of the considered model at epoch 29, with mean square errors of \(1.4698e-11\). The error histogram can be shown in Fig. 3c, where \(-4.1e-07\) is the best value we obtain in this example. Figure 3d displays the errors in the exact figure and the best fit of the training and testing data. Figure 4 shows the regression of the model under consideration for all data, testing data, and training data. The data is clearly on the regression line, demonstrating that the generated solution is accurately trained. The value of R is about 1.

as shown in Fig. 5a, b illustrates the performance of the considered model at epoch 1000, with mean square errors of \(3.1295e-05\). The error histogram can be shown in Fig. 5c, where \(-0.00197\) is the best value we obtain in this example. Figure 5d displays the best fit of the training and testing data and errors, as indicated in the exact figure. Figure 6 shows the regression of the model under consideration for all data, testing data, and training data. The data is clearly on the regression line, demonstrating that the generated solution is accurately trained. The value of R is about 1.

as shown in Fig. 7a represent the approach of ANN with Adam Bashforth method. Figure 7b illustrates the performance of the considered model at epoch 1000, with mean square errors of \(2.3443e-08\). Figure 7c displays the error histogram, and 0.001564 is the best value we obtain in this example. Figure 7d displays the errors in the same figure and the best fit of the training and testing data. Figure 8 displays the regression of the model under consideration for all data, testing data, and training data. The data is clearly on the regression line, demonstrating that the generated solution is accurately trained. The value of R is about 1.

as shown in Fig. 9a represent the approach of ANN with Adam Bashforth method. Figure 9b illustrates the performance of the considered model at epoch 193, with mean square errors of \(1.4342e-12\). Figure 9c displays the error histogram, and \(-61e-08\) is the best value we obtain. Figure 9d displays the errors stated in the same figure and the best fit of the training and testing data. Figure 10 displays the regression of the model under consideration for all data, testing data, and training data. The data is clearly on the regression line, demonstrating that the generated solution is accurately trained. The value of R is about 1.

as shown in Fig. 11a represent the approach of ANN with Adam Bashforth method. With mean square errors of \(9.6556e-14\) at epoch 8, the performance of the studied model is displayed in Fig. 11b, c displays the error histogram, and \(-8.3e-08\) is the best value we obtain in this situation. Figure 11d displays the best fit of the training and testing data and errors in the same figure. The model under consideration’s regression is displayed in Fig. 12 for all data, testing, and training. These graphs show that the data is on the regression line, indicating that the derived solution was accurately trained. The value of R is also approximately 1.

Application: informing hepatitis B control strategies

The comprehensive analysis of the fractional-order HBV transmission model offer important insights that can inform the development of effective public health strategies for controlling hepatitis B virus infection.

One key insight from the model is the identification of critical thresholds for the basic reproduction number (\(R_0\)) and the fractional derivative order (\(\alpha \)). The analysis revealed that when \(R_0\) is below a critical value and the fractional order \(\alpha \) is within a certain range, the disease-free equilibrium is stable, indicating the potential for successful disease control. This information can guide public health authorities in setting targeted goals for reducing HBV transmission rates and designing vaccination programs to achieve the necessary reduction in \(R_0\) to drive the system towards disease elimination.

Furthermore, the model’s predictions on the long-term dynamics of HBV infection, including the existence of endemic equilibria and the potential for backward bifurcations, can inform the design of treatment protocols and public awareness campaigns. By understanding the conditions under which the disease may persist or resurge, interventions can be tailored to address the specific challenges posed by HBV transmission in different epidemiological settings.

The model’s ability to capture the non-linear and memory-dependent nature of HBV infection dynamics through the use of fractional derivatives also presents opportunities for more accurate forecasting of disease trends. By calibrating the model parameters to match real-world HBV incidence data, public health authorities can leverage the model’s predictive capabilities to anticipate future disease patterns and allocate resources more effectively for prevention, early detection, and treatment programs.

Overall, the insights gained from the fractional HBV transmission model can serve as a valuable tool for informing the development and implementation of comprehensive hepatitis B control strategies, ultimately contributing to the reduction of the global burden of this infectious disease.

Conclusion

The key findings and contributions of this study are:

-

Developed a fractional model to describe the kinetics of hepatitis B (HBV) transmission, incorporating the Caputo derivative and vaccine effects.

-

Determined the essential reproductive value and equilibria of the proposed fractional HBV model.

-

Conducted a qualitative analysis of the problem’s approximative root using Fixed Point Theory.

-

Employed the Adams-Bashforth predictor-corrector scheme to evaluate the iterative approximate technique for the fractional system.

-

Provided graphical representations to compare the results for different noninteger orders.

-

Utilized Artificial Neural Network (ANN) techniques to partition the dataset into training, testing, and validation categories, with a comprehensive examination of the dataset’s characteristics and behaviors within these divisions.

Future research directions include:

-

Incorporating additional factors specific to hepatitis.

-

Conducting sensitivity analysis to identify influential parameters.

-

Exploring spatio-temporal and multi-scale modeling approaches.

-

Investigating optimal control strategies and interventions.

-

Validating the model and quantifying uncertainties.

These avenues of research can further enhance our understanding of hepatitis transmission dynamics and inform effective decision-making to combat the disease.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reason-able request.

References

Hu, M. & Chen, W. Assessment of total economic burden of chronic hepatitis B (CHB)-related diseases in Beijing and Guangzhou, China. Value Health 12, S89–S92 (2009).

Nowak, M. & May, R. M. Virus Dynamics: Mathematical Principles of Immunology and Virology: Mathematical Principles of Immunology and Virology (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000).

Wodarz, D., May, R. M. & Nowak, M. A. The role of antigen-independent persistence of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 12(4), 467–477 (2000).

Nowak, M. A. et al. Viral dynamics in hepatitis B virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93(9), 4398–4402 (1996).

Din, A., Li, Y. & Yusuf, A. Delayed hepatitis B epidemic model with stochastic analysis. Chaos Solitons Fractals 146, 110839 (2021).

Ullah, S., Altaf Khan, M. & Farooq, M. A new fractional model for the dynamics of the hepatitis B virus using the Caputo-Fabrizio derivative. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 133, 1–14 (2018).

Khan, A. et al. Modeling and sensitivity analysis of HBV epidemic model with convex incidence rate. Res. Phys. 22, 103836 (2021).

Arif, M. S., Raza, A., Rafiq, M. & Bibi, M. A reliable numerical analysis for stochastic hepatitis B virus epidemic model with the migration effect. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A Sci. 43, 2477–2492 (2019).

Lu, Q. Stability of SIRS system with random perturbations. Physica A 388(18), 3677–3686 (2009).

Wang, F. et al. Numerical solution of traveling waves in chemical kinetics: Time-fractional fishers equations. Fractals 30(02), 2240051 (2022).

Chu, Y. M., Shankaralingappa, B. M., Gireesha, B. J., Alzahrani, F., Khan, M. I., & Khan, S. U. (2022). RETRACTED: Combined impact of Cattaneo-Christov double diffusion and radiative heat flux on bio-convective flow of Maxwell liquid configured by a stretched nano-material surface.

He, Z. Y., Abbes, A., Jahanshahi, H., Alotaibi, N. D. & Wang, Y. Fractional-order discrete-time SIR epidemic model with vaccination: Chaos and complexity. Mathematics 10(2), 165 (2022).

Zhao, T. H. et al. A fuzzy-based strategy to suppress the novel coronavirus (2019-NCOV) massive outbreak. Appl. Comput. Math. 20(1), 160–176 (2021).

Atangana, A., & Baleanu, D. (2016). New fractional derivatives with nonlocal and non-singular kernel: theory and application to heat transfer model. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.03408.

Atangana, A. & Koca, I. Chaos in a simple nonlinear system with Atangana-Baleanu derivatives with fractional order. Chaos Solitons Fractals 89, 447–454 (2016).

Din, A., Shah, K., Seadawy, A., Alrabaiah, H. & Baleanu, D. On a new conceptual mathematical model dealing the current novel coronavirus-19 infectious disease. Res. Phys. 19, 103510 (2020).

Li, X. P. et al. A new Hepatitis B model in light of asymptomatic carriers and vaccination study through Atangana-Baleanu derivative. Res. Phys.29, 104603 (2021).

Zafar, Z. U. A., Tunç, C., Ali, N., Zaman, G. & Thounthong, P. Dynamics of an arbitrary order model of toxoplasmosis ailment in human and cat inhabitants. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 15(1), 882–896 (2021).

Zafar, Z. U. A., Ali, N. & Baleanu, D. Dynamics and numerical investigations of a fractional-order model of toxoplasmosis in the population of human and cats. Chaos Solitons Fractals 151, 111261 (2021).

Zafar, Z. U. A. et al. Numerical simulation and analysis of the stochastic hiv/aids model in fractional order. Res. Phys. 53, 106995 (2023).

Zafar, Z. U. A., Zaib, S., Hussain, M. T., Tunç, C. & Javeed, S. Analysis and numerical simulation of tuberculosis model using different fractional derivatives. Chaos Solitons Fractals 160, 112202 (2022).

Ahmad, Z., Bonanomi, G., di Serafino, D. & Giannino, F. Transmission dynamics and sensitivity analysis of pine wilt disease with asymptomatic carriers via fractal-fractional differential operator of Mittag-Leffler kernel. Appl. Numer. Math. 185, 446–465 (2023).

Shah, K. et al. Unraveling pine wilt disease: Comparative study of stochastic and deterministic model using spectral method. Expert Syst. Appl. 240, 122407 (2024).

Sinan, M. et al. Fractional order mathematical modeling of typhoid fever disease. Res. Phys. 32, 105044 (2022).

Sinan, M. et al. Fractional mathematical modeling of malaria disease with treatment & insecticides. Res. Phys. 34, 105220 (2022).

Sami, A., Ali, A., Shafqat, R., Pakkaranang, N. & Ur Rahmamn, M. Analysis of food chain mathematical model under fractal fractional Caputo derivative. Math. Biosci. Eng. 20(2), 2094–2109 (2023).

Anjam, Y. N. et al. A fractional order investigation of smoking model using Caputo-Fabrizio differential operator. Fractal Fract. 6(11), 623 (2022).

Li, B. & Eskandari, Z. Dynamical analysis of a discrete-time SIR epidemic model. J. Franklin Inst. 360(12), 7989–8007 (2023).

Zhu, X., Xia, P., He, Q., Ni, Z. & Ni, L. Ensemble classifier design based on perturbation binary salp swarm algorithm for classification. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 135(1), 653–671 (2023).

Zafar, Z. U. A. et al. Fractional-order dynamics of human papillomavirus. Res. Phys. 34, 105281 (2022).

Ahmad, Z. et al. Fractal-fractional sirs model for the disease dynamics in both prey and predator with singular and nonsingular kernels. J. Biol. Syst. 6, 1–34 (2024).

Shepard, C. W., Simard, E. P., Finelli, L., Fiore, A. E. & Bell, B. P. Hepatitis B virus infection: Epidemiology and vaccination. Epidemiol. Rev. 28(1), 112–125 (2006).

Zhang, J., Zou, S. & Giulivi, A. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in Canada. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 12(6), 345–350 (2001).

Din, A., Li, Y., Yusuf, A. & Ali, A. I. Caputo type fractional operator applied to Hepatitis B system. Fractals 30(01), 2240023 (2022).

Din, A. & Li, Y. Stationary distribution extinction and optimal control for the stochastic hepatitis B epidemic model with partial immunity. Phys. Scr. 96(7), 074005 (2021).

Alnahdi, A. S., Shafqat, R., Niazi, A. U. K. & Jeelani, M. B. Pattern formation induced by fuzzy fractional-order model of COVID-19. Axioms 11(7), 313 (2022).

Abuasbeh, K., Shafqat, R., Alsinai, A. & Awadalla, M. Analysis of the mathematical modelling of COVID-19 by using mild solution with delay Caputo operator. Symmetry 15(2), 286 (2023).

Liu, P., Din, A. & Zarin, R. Numerical dynamics and fractional modeling of hepatitis B virus model with non-singular and non-local kernels. Res. Phys. 39, 105757 (2022).

Caputo, M. & Fabrizio, M. A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Prog. Fract. Diff. Appl. 1(2), 73–85 (2015).

Caputo, M. & Fabrizio, M. Applications of new time and spatial fractional derivatives with exponential kernels. Prog. Fract. Diff. Appl. 2(1), 1–11 (2016).

El-Saka, H. A. A. The fractional-order SIS epidemic model with variable population size. J. Egyptian Math. Soc. 22(1), 50–54 (2014).

Din, A., Li, Y., Yusuf, A. & Ali, A. I. Caputo type fractional operator applied to Hepatitis B system. Fractals 30(01), 2240023 (2022).

Ali, Z., Zada, A. & Shah, K. Ulam stability to a toppled systems of nonlinear implicit fractional order boundary value problem. Bound. Value Problems 2018, 1–16 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by “Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R733), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All author’s contributed equally to the writing of this paper. All author’s read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Turab, A., Shafqat, R., Muhammad, S. et al. Predictive modeling of hepatitis B viral dynamics: a caputo derivative-based approach using artificial neural networks. Sci Rep 14, 21853 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70788-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70788-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Poliomyelitis dynamics with fractional order derivatives and deep neural networks

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Applied modeling of smoking behavior: a computational approach using generalized caputo formulation

Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computing (2025)

-

Analyzing a coupled dynamical system of materials recycling in chemostat systems with artificial deep neural network

Modeling Earth Systems and Environment (2025)