Abstract

The first-order second-moment checking point method was introduced to judge the instability probability and evaluate the stability of the TCURM. The frequency–response stability calculation and the reliability results were compared, and a frequency–response stability and reliability analysis method was proposed. Taking the Zengziyan W12# unstable rock mass in Nanchuan, Chongqing, China, as an example, the calculation shows that the dynamic indexes and geological indexes decrease as the stiffness of the deterioration area decreases. According to the statistical data of the laboratory test and the field investigation, reliability theory is used to evaluate the stability of the TCURM, and the failure probabilities are 80.3% and 96.27% under natural and saturated conditions, which correspond to states of poor stability and instability, respectively. The reliability evaluation results are consistent with the conclusion of the frequency–response stability analysis. The new method can provide a theoretical basis for developing the dynamic monitoring and early warning indicators of the TCURM and disaster prevention and mitigation in mountainous areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rock mass collapse usually occurs suddenly. The slope's surface displacement occurs after the formation of the internal fracture of the rock mass. However, monitoring points distributed on the slope's surface or geophysical exploration inside the slope are restricted by the landform, hydrogeological conditions, drilling risk, and cost, resulting in the difficulty of short-term or real-time prediction of collapse disasters. Therefore, it is urgent to study the dynamic parameters that reflect the current characteristics of unstable rock mass1. Using vibration parameters to characterize the precursor of collapse is an effective means to identify and monitor unstable rock masses2,3 ; it has apparent advantages in rock mass stability analysis, damage identification, and strength calculation4. The natural frequency of the unstable rock mass is an inherent attribute. Various damage mechanisms can reduce the stiffness, natural frequency, and stability of unstable rock masses5. Therefore, we can effectively avoid the negative impact of collapse disasters on all kinds of residential buildings and infrastructure by monitoring the natural vibration frequency index, which can be applied to analyze the real-time stability of a tower-column unstable rock mass (TCURM), dynamically predict the instability time, and issue early warning information in a timely manner.

The structure's mass and stiffness influence the natural modal parameters such as the vibration mode and frequency. The deterioration of the structure leads to a decrease in stiffness and then changes the modal parameters6. The natural vibration frequency used to predict rock mass collapse has been reported for decades. For example, Levy7 used seismometers and extensometers to detect the first resonance frequency of the limestone column at the Chamousset site and compared it with finite element model results; Moore8,9 employed ambient resonance measurements of a freestanding rock to measure the elastic modulus of in situ rock masses and identified the first resonant modes of a 120-m high freestanding rock monolith. Valentin3 found the rock column slenderness influences the resonance frequency because the slenderness will change the mass and rigidity of the rock column.

Contact monitoring methods for obtaining the natural vibration frequency of structures require external force excitation and pulsation. They require a considerable input excitation energy or high instrument accuracy to capture frequency response signals, so their application in large rock slopes is limited. In recent years, laser Doppler vibrometry (LDV) has used optical principles and noncontact nondestructive monitoring modes to obtain the natural vibration frequency of unstable rock masses. It gradually showed advantages in the dynamic monitoring of high-level and large-scale high and steep rock slopes10. For example, Siringoringo and Fujino11 introduced the principle and algorithm of LDV to obtain modal parameters. It has significant advantages over the traditional artificial excitation method in any working conditions, including all weather conditions.

Unstable rock masses are primarily developed with cliff landforms, controlled by a deep and sizeable structural plane with a thin, high shape and free surface. Suppose the size of a rock mass in the vertical Z direction is much larger than that in the two horizontal X and Y directions (10 times or more) and the size ratio in the X and Y directions is less than or equal to 4. Such a rock mass can be defined as a tower-column unstable rock mass12. The stiffness of a TCURM has spatial variability because of the nonuniform deterioration of the rock mass. Key blocks control the instability mode, but dynamic models and theoretical research have not been reported13. In addition, the uniaxial compressive strength criterion is usually used to analyze the stability of a tower-column unstable rock mass. The compressive strength of the rock mass is related to the integrity of the rock mass, and the acoustic velocity measurement obtains the integrity coefficient of the rock mass. With this method, water is injected into the borehole, and the vibration signal in the adjacent borehole is captured by applying excitation on the surface. However, the cross-hole acoustic velocity measurement test has application limitations in the TCURM on a cliff14. Therefore, a new method for obtaining the compressive strength of the TCURM on steep and high slopes can be explored in combination with the self-resonance frequency monitoring index to reduce exploration risks and economic costs.

There are many uncertainties in the geotechnical parameters, such as geological model, frequency, strength, and persistence of the influential factors used for the unstable rock slope stability analysis, so the traditional deterministic analysis method has some limitations15. Some scholars have introduced the reliability analysis methods to calculate the instability probability of unstable rock collapse and slope instability, such as a plain failure mode in the jointed rock mass17,18, a rock wedge stability analysis19,20, a toppling failure mode in an unstable rock mass21. However, the reliability analysis method has not been used to evaluate the instability probability of the fracturing-induced failure mode of a TCURM. Additionally, the reliability analysis is different from the traditional deterministic stability analysis method, so these approaches can mutually verify the unstable rock stability evaluation results.

In conclusion, due to the quality difference in rock mass between the top and the bottom of a TCURM, a TCURM can be divided into the incomplete deterioration area in the middle and upper parts of the rock mass and the deterioration area at the bottom. Then, a two-degree-of-freedom vibration mechanics model can be established. The natural vibration frequency (fundamental frequency) used for stability analysis, instability prediction and early warning of the unstable rock mass is explored. A new method for obtaining the compressive strength of a rock mass suitable for a limestone area is proposed. At the same time, the optimized first-order second-moment method (FOSM) is proposed to analyze the instability probability of the TCURM. The FOSM can be used to verify the rationality of the frequency–response stability analysis method (FRSA). Furthermore, we creatively combine the FOSM and the FRSA to obtain a frequency–response reliability stability analysis method (FRRSA) which can provide a theoretical basis for the dynamic monitoring and early warning indicators for the TCURM disaster prevention and mitigation.

Geomorphic evolution and dynamic monitoring stage

From formation (birth) to collapse and accumulation (death), a TCURM, with a gentle dip, has a geomorphic evolution process with periodic characteristics22,23. Figure 1 shows the process: (a) Initial formation stage: Due to the intermittent motion and uplift of the Earth's crust, the river exposes soft-hard interbedded strata, which forms a steep and high slope. The tensile stress concentrates on the crest of the slope, resulting in unloading tensile cracks. The soft-hard interbedded strata at the toe of the slope undergo differential unloading rebound deformation and bear the weight of the upper rock mass, resulting in both the unloading tensile cracks and the compression-induced tensile cracks (like the vertical tensile cracks formed under the axial load in the unconfined compressive strength test) near the base interface. (b) The formation stage of the control fissure: The unloading crack at the crest of the slope extends downward, and the compression-induced tensile crack at the toe of the slope propagates upward. (c) Differential deterioration stage of the rock mass: The control fissure separates the unstable rock mass from the parent rock. Under the freeze‒thaw action, dissolution, water-induced weakening, and a self-weight load of the upper part of the unstable rock mass, with the further development of dissolution holes and fissures, the compression-induced tensile cracks continue to develop, and the rock mass strength decreases continuously. (d) Deterioration aggravation stage: When the rock mass quality in the deterioration area at the bottom of the TCURM decreases to a threshold value, sudden fracturing and ejection of the detached rock will occur, and the TCURM behavior transforms from static instability to a dynamic process. (e) Slumping fragmentation stage: The incomplete deterioration area in the upper part of the TCURM impacts the base at a specific speed and disintegrates continuously under the strong shock wave in the slumping period. (f) Accumulation stage: The broken stones move along the valley and accumulate along the route.

As the deterioration aggravation stage corresponds to the critical instability state, dynamic monitoring instruments can obtain data with high efficiency and high frequency; engineers can analyze and obtain feedback in time, and the management department can effectively save monitoring costs and improve decision-making accuracy. Therefore, the dynamic monitoring and early warning period should be performed in the deterioration aggravation stage in Fig. 1d. According to the on-site geological experience and the theoretical damage-catastrophe calculation results in the deterioration area, we can judge whether critical instability starts at the deterioration aggravation stage.

At present, relevant dynamic monitoring instruments have appeared on the market. However, the vibration mechanics model and the relevant theory still need improvement. Therefore, we discuss the vibration mechanics model below.

Frequency–response stability analysis method

A two-degree-of-freedom vibration mechanical model

The TCURM, with a triangular prism shape and a gentle stratum dip, is located on the second Zengziyan cliff in the Nanchuan District of Chongqing. The second cliff consists of limestone from Groups 3–5 of the lower Permian Maokou Formation (P1m3+4+5) and shale with limestone in Group 2 of the lower Permian Maokou Formation (P1m2). The first cliff comprises limestone of Group 1 of the lower Permian Maokou Formation (P1m1) and the lower Permian Qixia Formation (P1q). Three groups of control fissures are developed in the unstable rock mass, of which two groups are vertical and orthogonal unloading fractures, which propagate from top to bottom, with an extended length of approximately 200 m and a fracture width of 3 ~ 10 m. The other group is in the near-horizontal orientation (Fig. 2).

As usual, the free-standing column or slab has a toppling failure mode, but the Zengziyan cliff rarely shows a special collapse mode. The TCURM collapses vertically, accompanied by fragmentation during the slumping process. The survey results demonstrate that the bottom deterioration area is a water accumulation and circulation area. The stress concentrates, and the rock mass strength decreases most due to a significant dissolution phenomenon. Under the self-weight load of the rock mass in the upper incomplete deterioration area, the rock mass in the deterioration area appears to fracture, which corresponds to a compression-induced instability initiation mechanism at the bottom of the unstable rock mass24.

Two groups of vertical unloading fissures cut and separate the TCURM from the parent rock, as shown in the photographs in Fig. 3a,b. The damage and deterioration degree at the bottom of the unstable rock mass becomes worse when undergoing various geological forces, such as self-weight, weathering, and dissolution. Thus, the TCURM consists of an upper incomplete deterioration area and a lower complete deterioration area from top to bottom. The binary system in Fig. 3b is selected as the research object.

The generalized process of mechanical model of the TCURM; The submap (a) is the generalized model of the cliff; The submap (b) is the tower column unstable rock mass; The submap (c) is the two-degree-of-freedom vibration mechanical model of the TCURM; The submap (d) is the mechanics analysis of the tower column unstable rock mass.

The following is the purpose and procedure for constructing a two-degree-of-freedom vibration mechanics model. The first step is to construct a two DOF model representing the TCURM. Secondly, it’s easy to get the theoretical dynamic response parameters such as the natural frequency which can reflect the deterioration degree of the rock in the bottom of the TCURM. Thirdly, it points out where and which parameter to measure according to the analysis of the two DOF model of the TCURM. So the two DOF model in Fig. 3 is the theoretical foundation for analysis of the TCURM. Furthermore, the reduction of the natural frequency response will reflect the stability state of the TCURM.

Based on the purpose, A two-degree-of-freedom vibration mechanics model is obtained by applying the mass concentration method of vibration mechanics (Fig. 3c). The upper incomplete deterioration area is simplified as particle m2, whose vibration displacement under dead weight load m2g is u2. The lower deterioration area is simplified as particle m1, whose vibration displacement under dead weight load m1g is u1. Spring k2 connects the two particles, and spring k1 connects particle m1 with the base. The force on the two particles is shown in Fig. 3d.

We assume that (1) the geometric parameters such as the height H1 and horizontal cross-sectional area A1 of the deterioration area and the height H2 and horizontal cross-sectional area A2 of the incomplete deterioration area remain unchanged (Fig. 2b). (2) In a simple harmonic vibration process, the mass of the two particles, m1 and m2, is constant, and the system meets the deformation synchronization principle. (3) The rock at the bottom is deteriorating, therefore, the stiffness coefficient k1 of the bottom should be a decreasing function of time and the variation of k1 would cause the motion of the system. The rock in the upper portion is a non-deterioration area where the stiffness coefficient k2 should keep the same in a long time.

According to Fig. 3d, the motion equation in matrix form is established for the two-degree-of-freedom undamped vibration system by using the D'Alembert principle, as shown in Eq. (1):

where \(\mathop {u_{1} }\limits^{..}\) is the acceleration of particle m1 (m/s2) and \(\mathop {u_{2} }\limits^{..}\) is the acceleration of particle m2 (m/s2). The meanings of the other symbols are the same as before.

where ki is the stiffness coefficient of the ith spring (N/m), and the subscript i is either 1 or 2; Ei, Ai, and Hi are the elastic modulus (MPa), the sectional area (m2), and the height (m) of the ith rock mass, respectively; i = 1 represents the simplified particle in the bottom deterioration area of the rock mass; i = 2 represents the simplified particle in the incomplete deterioration area in the middle and upper part of the rock mass.

Suppose that Eq. (1) has a simple harmonic solution of displacement, as shown in Eq. (3):

where φ1 and φ2 are the particle amplitudes (m), ω is the circular frequency (Hz), and θ is the initial phase.

Substituting Eq. (3) into Eq. (1), the homogeneous characteristic equation can be obtained, as shown in Eq. (4):

The necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of a nonzero solution of the vibration displacement in the two-degree-of-freedom system is that the coefficient determinant of Eq. (4) is zero, that is,

By solving the frequency Eq. (5), the frequencies of each order of the two-degree-of-freedom system can be obtained, as shown in Eqs. (6) and (7):

where ω1 is the first-order circular frequency (Hz) and ω2 is the second-order circular frequency (Hz). The meanings of the other symbols are the same as before.

ω1 and ω2 are related to the mass distribution and the stiffness of the system and have nothing to do with the cause of vibration, so they are the system’s inherent attributes. Equations (8) and (9) show the corresponding first-order natural frequency f1t and the second-order natural frequency f2t:

In theory, a laser Doppler vibrometer can monitor the natural frequency of a TCURM, and the change in the natural frequency can reflect the deterioration degree of the binary system. With the decrease in stiffness, the natural frequency of the unstable rock mass decreases, and the rock mass’s deterioration degree worsens.

Frequency–response reduction coefficient

At the initial formation stage of the unstable rock mass, there is no apparent difference in the physical and mechanical indices of the rock mass with the same lithology, and the dynamic characteristics are almost the same. With the effects of unloading rebounding, weathering, root splitting, self-weight loading, and other factors, the different parts of the TCURM show different deterioration trends, the deterioration degree of the bottom is much worse than that of the top, and the dynamic parameters decrease significantly. The first-order natural frequency, which is a primary vibration frequency–response index, is the fundamental frequency, with the lowest vibration frequency and the most prolonged vibration period. Therefore, the fundamental frequency (the first-order natural frequency) is chosen as the primary vibration monitoring index of the TCURM. Obviously, over time, the rock mass strength deteriorates continuously, and the fundamental frequency f1, which is a function of time t, decreases accordingly. Based on this, the frequency–response reduction coefficient Dt of the TCURM at any time t is defined, as shown in Eq. (10)4:

where f1t is the fundamental frequency monitoring index at time t, (Hz), and f1(t0) is the fundamental frequency at the initial time of t0, (Hz). At the initial formation time of the unstable rock mass, the difference in the rock mass’s physical and mechanical indices in different parts is non-significant. The elastic modulus Ei can be obtained from the slightly weathered rock when the fundamental frequency at the initial time is calculated by applying Eqs. (2) and (8), (MPa).

The rock mass damage factor De1 which reflects the proportion of defects in a particular state is introduced to represent the damage and deterioration degree of the rock mass through the decrease in the fundamental frequency, as shown in Eq. (11)22:

Frequency–response stability coefficient

The mechanical model of the TCURM is similar to a large-scale uniaxial compression test24,25, and the rock mass stability can be approximately judged according to the uniaxial compressive strength criterion. The stability coefficient is shown in Eq. (12)26:

where [σb] is the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of the rock mass (MPa). σ is the compressive stress on the top surface of the rock mass deterioration area (MPa).

The UCS [σb] of the rock mass in the limestone area is generally obtained by the uniaxial compressive strength of the indoor rock test, which is reduced according to engineering experience. The reduction coefficient is related to the lithology, complexity, structural plane development, and engineering experience. It lacks a theoretical basis and appears to have apparent subjectivity. The quantitative equivalent acquisition method of the rock mass compressive strength is introduced in detail below.

The combination of the rock mass basic quality (BQ) classification, the rock mass rating (RMR) classification, and the geological strength index (GSI) system can provide a theoretical method for quantitative reduction of the rock mass compressive strength, such as Eqs. (13)–(17)14:

where

where Kv is the integrity coefficient of the rock mass, which is obtained by the acoustic velocity measurement method; Rc is the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of the rock (MPa); GSI is the geological intensity index27 in the Hoek‒Brown criterion (H-B criterion); η is the disturbance factor between [0,1], and 0 is taken when there is no apparent artificial disturbance; mi is the material constant of the intact rock, and the limestone is taken as 7; mb, s and a are the modified generalized Hoek‒Brown parameters; and σ3 is the minor principal stress (MPa), which is 0 under uniaxial stress. The meanings of other parameters are the same as before.

Equation (17) fits the gentle slope terrain where drilling rigs are easily erected, such as the slope of the reservoir bank. When there is a reliable water source, an exploration test can be carried out to obtain the rock integrity coefficient Kv and calculate the GSI and the UCS. However, for the TCURM on a large steep and high slope, the toe of a cliff is the crucial part that controls the overall stability of the unstable rock mass. Conventional drilling methods have disadvantages, such as deep working depths, numerous drilling holes, high capital costs, low work efficiency, potential limestone leakage, and drilling damage. Therefore, obtaining the integrity coefficient Kv by the acoustic velocity measurement method is difficult.

In order to solve the above problem, the dynamic index (the integrity coefficient Kv) should be replaced equivalently. As we know, the better the rock mass integrity is, the faster the acoustic wave's transmission speed (the acoustic velocity) is and the higher the fundamental frequency is. Therefore, it is assumed that for the same rock mass, the above two dynamic indices (the integrity coefficient and the fundamental frequency) may describe the deterioration degree of the rock mass, both of which must have a specific scientific internal relationship.

The literature14 defines the deterioration degree of the rock mass as a damage factor De2 = 1-kV. Theoretically, the deterioration degree of the same rock mass at the same time is an objective attribute, and the damage factor obtained by different methods should be the same; that is, the damage factor De2 obtained by the acoustic velocity measurement method and the damage factor De1 obtained by the fundamental frequency monitoring method should be equal. Combined with Eq. (11), let De1 = De2; then, Kv = Dt.

Therefore, the integrity coefficient Kv of the rock mass in Eq. (17) can be replaced by the frequency–response reduction coefficient D(t) of Eq. (10), as shown in Eq. (18):

The frequency–response stability coefficient of the rock mass can be obtained by the following steps: First, we can obtain the frequency–response reduction coefficient Dt according to Eq. (10) by obtaining the fundamental frequency of the TCURM measured at different times. Second, the frequency response reduction coefficient Dt is inserted into Eq. (18) to obtain the geological strength index (GSI). Third, it's easy to get the compressive strength [σb] based on Eqs. (13)–(16) and (18). Fourth, by combining the compressive strength [σb] (Eq. (13)) with the stability coefficient Fs (Eq. (12)), we can obtain the frequency response stability coefficient Fsd. Fifth, the variation of the frequency–response stability coefficient with time can be revealed to estimate the instability of the TCURM by measuring the fundamental frequency of the TCURM.

In addition, due to the lack of a stability classification standard for the compression-induced instability mode of the TCURM at present, the instability analysis can be implemented by referring to the relevant provisions on the evaluation and prediction of the unstable rock mass collapse in the ‘Exploration Code for Geological Disaster Prevention and Control Engineering (DB50/T 143–2018)’.

The frequency–response stability analysis method proposed above is a deterministic analysis method. Due to many uncertainties, such as the geomechanical model, which is difficult to reflect the complexity in nature, and the significant spatial variation of physical and mechanical parameters, reliability theory can verify the rationality of the proposed deterministic analysis method1,4,5. Meanwhile, by combining the deterministic analysis method with the reliability theory, a non-deterministic frequency–response stability reliability analysis method of the TCURM can be obtained. Therefore, the reliability theory is introduced below.

Reliability analysis method

The first-order reliability method (FORM) is one of the most commonly used calculation methods in rock slope stability analysis and includes the first-order second-moment method (FOSM) and the advanced second-moment method (ASMM)28. This study intends to combine the frequency–response stability calculation method with the reliability method. First, the performance function (Eq. (19)) can be constructed according to the frequency–response stability coefficient of the TCURM (Eq. (12)). Second, the advanced second-moment method (ASMM) is used to evaluate the reliability of the TCURM stability.

We make two assumptions: (1) The confining pressure σ3 in the Hoek‒Brown criterion and the blasting disturbance factor D are not considered under the uniaxial compression condition. (2) The rock uniaxial compressive strength Rc, the GSI, and the H-B parameters (s and a) follow the standard normal distribution.

Based on the above hypothesis, the instability performance function g(X) and the state criterion of the TCURM are established, as shown in Eq. (19):

where X = [X1, X2, …, Xn] represents the random variable, and the random variable of the TCURM based on the H-B criterion is X = [Rc, s, a].

According to the ASMM, the mean value μz, the standard deviation σz, the reliability index β, the sensitivity coefficient αXi, the extreme point xi*, and the failure probability Pf of the performance function are obtained, as shown in Eqs. (20)-(25)29:

where Xi is a vector including the random variables Rc, s, and a; xi* represents the extreme point of the random variable when the performance function is in a limit state; Φ(·) is the standard normal distribution function; μxi represents the mean value of the random variable xi; and σXi represents the standard deviation of the random variable xi.

After obtaining the unstable rock mass’s failure probability Pf, we can evaluate the stability state of the TCURM based on the stability evaluation criteria (Table 1) provided by the literature21.

It should be noted that the stability reliability of the TCURM, calculated with engineering test parameters and field investigation data, is not limited to verifying the frequency–response stability analysis method proposed in this study. Obviously, combining the deterministic analysis method and the nondeterministic stability analysis method to obtain the TCURM frequency–response stability reliability analysis method has a more significant engineering application value than each method alone. The specific steps are shown in.

Case study

The geometric and physical parameters are determined from the literature12 and the "Construction drawing of the unstable rock mass numbered W29# and W23# treatment project of Jinfoshan, Nanchuan District, Chongqing" report. The height H1 of the deterioration area of the W12# unstable rock mass is 48 m, the height H2 of the incomplete deterioration area is 192 m, the cross-sectional area is approximately 804.25 m2, and the limestone unit weight is 26.5 kN/m3. The elastic modulus of the moderately weathered limestone is 43.68 GPa, the elastic modulus of the slightly weathered limestone is 62.4 GPa, the natural uniaxial compressive strength of the rock is 51.17 MPa, the saturated uniaxial compressive strength of the rock is 42.07 MPa, and the compressive stress σ on the deterioration area's top surface is 5.088 MPa (Fig. 4).

The deterioration law of the stiffness coefficient by the time

A large number of limestone rocks in the deterioration area of the W12# unstable rock mass were taken by us to conduct some indoor experiments to see how the strength of the rock varies with time in the study (Fig. 5)30. We analyzed and obtained the stiffness coefficient results in Fig. 6.

It shows that the stiffness coefficient decreases with time in any acidic environment. The stiffness coefficient decreases from 971.29 × 106 N/m to 671.2 × 106 N/m when the PH is 6, and the stiffness coefficient decreases dramatically from 807.5 × 106 N/m to 244.24 × 106 N/m when the PH is 2. Therefore, it can be proved that the assumption that the stiffness coefficient decreases with time in “A two-degree-of-freedom vibration mechanical model” is justified.

Sensitivity analysis of the physical parameters

Since the physical properties of the rock mass in the deterioration area are weaker than those in the incomplete deterioration area, the elastic modulus of the moderately weathered limestone is assigned to the deterioration area's rock mass to calculate the stiffness coefficient k1; the elastic modulus of the slightly weathered limestone is assigned to the incomplete deterioration area to calculate the stiffness coefficient k2. The following section studies the sensitivity of each physical parameter to the decrease in the stiffness coefficient k1 of the deterioration area.

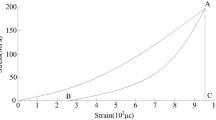

According to Eqs. (2), (8), (10), (12), (13), and (18), the deterioration law of each physical parameter with the deterioration area's stiffness coefficient k1 is obtained by MATLAB programming, as shown in Fig. 7. For example, the stiff coefficient k1 and k2 will be obtained by the basic data of the case. Then suppose the stiff coefficient k2 which reflects the condition of the incomplete deterioration area will not change and the stiff coefficient k1 which represents the condition of the complete deterioration area will decrease significantly with time. If the stiff coefficient k1 reaches 3 × 1011N/m, which shall be put into Eq. (1), the fundamental frequency f1 will be 2.85Hz.

It can be seen from Fig. 7 that (1) the fundamental frequency f1 decreases with decreasing stiffness coefficient k1 in the deterioration area. The fundamental frequency monitoring data can reflect the rock mass’s internal deterioration. The fundamental frequency decreases from 3.42 Hz to 1.75 Hz, with an absolute decrease of 1.67 Hz and a relative decrease of 48.8%. When the fundamental frequency is larger than 3.29 Hz, the TCURM does not reach the instability stage.

(2) The frequency–response stability coefficient (Fsd), the geological strength index (GSI), the frequency–response reduction coefficient (Dt), and the uniaxial compressive strength [σb] of the deterioration area's rock mass all show a nonlinear decreasing trend as the deterioration area's stiffness coefficient decreases, and the rate of decline accelerates. When the stiffness coefficient k1 of the deterioration area is larger than 3 × 1011 N/m, each parameter curve changes approximately linearly. When the stiffness coefficient k1 of the deterioration area is less than 3 × 1011 N/m, each curve has a steep drop. When the stiffness coefficient k1 of the deterioration area is 3 × 1011 N/m, the TCURM reaches the mutation point of compression-induced instability. The GSI at the mutation point is 55.7, the fundamental frequency f1 is 2.85 Hz, the frequency–response reduction coefficient Dt is 0.798 Hz, and the UCS [σb] of the rock mass in the deterioration area is 4.29 MPa.

(3) When the frequency–response stability coefficient Fsd is reduced to the critical state value of 1.0, the deterioration area stiffness coefficient is reduced to 5.66 × 1011 N/m, GSI is 60.14, fundamental frequency f1 is 3.29 Hz, frequency–response reduction coefficient Dt is 0.917, and [σb] of the rock mass in the deterioration area is 5.48 MPa.

Discussion

According to the acoustic emission test data of the Zengziyan limestone specimen in the literature31, when the damage degree reaches 0.2, the total damage degree curve increases sharply to approximately 0.7, and the peak strength of the rock specimen decreases sharply from approximately 126 MPa to a residual strength of approximately 40 MPa (Fig. 8). In Fig. 8, when the frequency–response reduction coefficient Dt is 0.798, the corresponding rock mass’s damage factor De1 is 0.202 in combination with Eq. (11), which is the same as the damage degree in the above literature. The frequency–response reduction coefficient and the damage factor based on the acoustic emission theory can characterize the damage degree of the rock mass.

Constitutive curves and damage degree evolution of the rock specimen under the compressive acoustic emission test31.

We combine the GSI value of 55.7 at the mutation point in Fig. 4 with Eqs. (13)–(16), and the peak compressive strength data of rock samples presented in the literature31 are used to determine a rock mass compressive strength of approximately 8.83 MPa, which is different from the rock mass compressive strength of 4.29 MPa under uniaxial compression calculated in this study. The reason for this difference is that the confining pressure corresponding to the peak compressive strength in the literature31 is 1 MPa, which makes the modified compressive strength of the rock mass higher than the uniaxial compressive strength of the rock mass in the deterioration area calculated theoretically in this study. On-site, the TCURM is separated from the parent rock, resulting in no confining pressure. Therefore, using the rock's uniaxial compressive strength is more convincing to modify the rock mass's compressive strength.

We collected rock samples at the W12# unstable rock mass collapse site and performed rock uniaxial compression testing with an RMT150C-type rock and concrete pressure machine (Fig. 9). The rock's uniaxial compressive strength of 72.25 MPa was modified to the rock mass's uniaxial compressive strength of 5.06 MPa in the deterioration area, combined with the GSI value of 55.7 selected from the mutation point in Fig. 7 and Eqs. (13)–(16) of the H-B criterion. This is 0.77 MPa larger than the UCS of 4.29 MPa calculated from the engineering test data (the rock's natural UCS is 51.17 MPa). The reason is that when engineers plan for engineering reinforcement design, the rock test data are first reduced according to engineering experience and then revised again according to the H-B guidelines in this study, which means a double reduction: artificially and theoretically. This study used the indoor rock test data, which were only modified according to the H-B criterion, so the compressive strength of the rock and the modified rock mass are slightly larger. From the engineering design perspective, the double reduction in the rock mass in the deterioration area is conservative and meets the engineering requirements. However, from the collapse disaster prediction view, overly conservative data may increase monitoring time and cost and even result in erroneous results32.

The overall process of the uniaxial compressive strength test of the rock; Submaps (a) and (b) are the collapsed place of the Zengziyan cliff where we climbed to collect the original rock blocks. Submaps (c) and (d) are the standard cylindrical specimens drilled from the original rock blocks; the diameter is 50 mm, and the height is 100 mm.

If not considering the rock mass strength attenuation in the deterioration area, the compressive stress induced by the upper incomplete deterioration area is much smaller than the rock mass compressive strength in the deterioration area. Thus, the deterioration area will be stable based on the theory of material mechanics. However, compression-induced instability may occur considering the in situ rock mass deterioration shown in the uniaxial compressive strength curve. This indicates that the rock mass deterioration effect can quantitatively explain the compression-induced instability mode of the TCURM collapse initiation mechanism.

In summary, the frequency–response stability coefficient can be obtained to judge the stability of the TCURM, with the fundamental frequency monitoring data obtained by the laser Doppler vibrometer in the field, combined with the theoretical calculation results (Fig. 7). Although there are no two similar TCURMs in the field, but the analysis methods and ideas proposed in this study can be used for reference.

It should also be noted that the unit of the stiffness coefficient in “The deterioration law of the stiffness coefficient by the time” is 106 N/m, which is different from the stiffness coefficient in “Sensitivity analysis of the physical parameters”, which is 109 N/m. The reason is that the height of the standard cylinder in “The deterioration law of the stiffness coefficient by the time” is 100mm and the height of the tower-column shaped unstable rock mass in “Sensitivity analysis of the physical parameters” is 240m, so the similar scale is nearly 2400 times. If we multiply the stiffness coefficient in “The deterioration law of the stiffness coefficient by the time” by 2400, the stiffness coefficient in “The deterioration law of the stiffness coefficient by the time” and “Sensitivity analysis of the physical parameters” are of the same unit order of magnitude.

The validation of the TCURM stability based on reliability theory

To further validate the frequency–response stability analysis method proposed in this study, a comparative analysis is carried out based on a geological field survey and reliability theory. First, the test parameters of the physical and mechanical indices of the Zengziyan rock mass are statistically analyzed to obtain its statistical indices. Second, the site investigation and statistics are carried out in the deterioration area at the bottom of the second cliff of the collapsed relic of the Zengziyan rock mass, and the statistics of the geological strength index GSI are obtained. The H-B parameters (s and a) are calculated in combination with Eqs. (15)–(16). Finally, according to the advanced first-order second-moment method (Eqs. (20)–(25)), the reliability index and failure probability under saturated and natural conditions are calculated with MATLAB programming. The results are shown in Table 2.

Conclusions can be made from the results in Table 2 and the assessment criteria in Table 1: (1) The instability probability under saturated conditions is 96.27%, which is unstable. The instability probability under natural conditions is 80.3%, which is a poor stability, indicating that the UCS of the rock mass has a significant influence on the stability of the compression-induced instability mode of the TCURM. (2) The average GSI from the field investigation is 53.57. According to the deterioration of the GSI and other physical parameters given in Fig. 4, the deterioration area stiffness is approximately 2.36 × 1011 N/m, the fundamental frequency f1 is 2.66 Hz, the frequency–response reduction coefficient Dt is 0.745, the UCS [σb] of the rock mass is 3.8 MPa, and the frequency–response stability coefficient FSd is 0.56 (instability). The results of the reliability theory analysis are consistent with the frequency–response stability analysis results. Calculating the stability of the TCURM according to the fundamental frequency monitoring data is reasonable and feasible.

Conclusions

The deterioration degree of a TCURM has a significant spatial variability, and the deterioration area with poor quality at the bottom controls its instability mode. A TCURM is composed of an incomplete deterioration area and a deterioration area. A two-degree-of-freedom vibration mechanics model is established according to the mass concentration method. The fundamental frequency used for the stability analysis, instability prediction and early warning of the unstable rock mass is explored. By literature comparison, laboratory tests, field investigations, and the ASMM of reliability theory, the rationality and feasibility of this method are verified, providing a new idea for the development of noncontact, nondestructive dynamic monitoring and early warning indicators of TCURMs. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

A two-degree-of-freedom vibration mechanics model of a TCURM is established. The frequency–response reduction coefficient is calculated by using the fundamental frequency. The GSI is obtained equivalently according to the damage theory. The formulas for the compressive strength of the rock mass in the deterioration area and the expression of the frequency–response stability coefficient are obtained based on the generalized Hoek‒Brown criterion.

-

(2)

The ASMM of the reliability theory is introduced. The performance function of the TCURM compression-induced instability model is established, which is mutually tested with the frequency–response stability analysis method and used to construct a frequency–response stability reliability analysis method.

-

(3)

Taking the W12# TCURM on the Zengziyan cliff of Nanchuan District in Chongqing municipality as an example, a sensitivity analysis of parameters such as the fundamental frequency, GSI, and frequency–response stability coefficient is carried out. When the fundamental frequency is larger than 3.29 Hz, the TCURM does not reach the instability stage. The calculation results of the frequency–response stability analysis method are discussed by employing the engineering test parameters, indoor testing, and a literature comparison. The engineering test parameters and the GSI of the field investigation are statistically analyzed. These results, combined with the ASMM, are used to determine the failure probabilities under natural and saturated conditions of 80.3% and 96.27%, respectively, which reflect poor stability and instability. The evaluation results are consistent with the results of the frequency–response stability analysis.

-

(4)

Furthermore, an indoor test model of a TCURM is established, and the laser Doppler vibrometer is used to verify the physical model. According to different geological conditions and unstable rock mass styles, the layout and number of natural vibration frequency monitoring points need further development.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Du, Y. et al. Safety monitoring experiment of unstable rock based on natural vibration frequency. Rock Soil Mech. 37(10), 3035–3040 (2016).

Yang, J. W., Bai, R. C., Yu, Y. J. & He, F. Inversion test and numerical verification on natural period of rock slope with weak layers. J. China Coal Soc. 40(S1), 69–75 (2015).

Valentin, J. et al. The dynamic response of prone-to-fall columns to ambient vibrations: comparison between measurements and numerical modelling. Geophys. J. Int. 2, 1–41 (2017).

Du, Y., Wu, Z. X., Xie, M. W., Liu, R. C. & Chen, C. Early-warning method of rock collapse and its experimental verification. J. China Coal Soc. 44(10), 3069–3075 (2019).

Du, Y., Lu, Y. D., Xie, M. W. & Jia, J. L. A new attempt for early warning of unstable rocks based on vibration parameters. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 4363–4368 (2020).

George, H. & Rene, B. T. Modal analysis for damage detection in structures. J. Struct. Eng. 117(10), 3042–3061 (1991).

Levy, C., Baillet, L., Jongmans, D., Mourot, P. & Hantz, D. Dynamic response of the Chamousset rock column (Western Alps, France). J. Geophys. Res. 2010(115), 1–13 (2010).

Moore, J. R., Geimer, P. R., Finnegan, R. & Thorne, M. S. Use of seismic resonance measurements to determine the elastic modulus of freestanding rock masses. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 51(12), 3937–3944 (2018).

Moore, J. R., Geimer, P. R., Finnegan, R. & Michel, C. Dynamic Analysis of a Large Freestanding Rock Tower (Castleton Tower, Utah). Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 109(5), 2125–2131 (2019).

Ma, G. C., Sawada, K., Yashima, A. & Saito, H. Experimental study of the applicability of the remotely positioned laser doppler vibrometer to rock-block stability assessment. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 48(2), 787–802 (2015).

Siringoringo, D. M. & Fujino, Y. Noncontact operational modal analysis of structural members by laser doppler vibrometer. Comput.-Aided Civ. Inf. 24(4), 249–265 (2009).

He, K., Yin, Y. P., Li, B. & Chen, C. L. The mechanism of the bottom-crashing rockfall of a massive layered carbonate rock mass at Zengziyan, Chongqing. China. J. Earth. Syst. Sci. 128(4), 103–116 (2019).

He, K., Chen, C. L., Feng, Z., Li, B. & Pan, L. B. A review on the collapse hazards of tower-shaped rock. J. Geomech. 22(3), 714–724 (2016).

Yin, Y. P., Yan, G. Q., Huang, B. L., Dai, Z. W. & Qin, Z. Geological strength index of the slope rock mass deterioration process of the hydro-fluctuation belt in the Three Gorges Reservoir. China. ASCE J. Hydraul. Div. 51(8), 883–896 (2020).

Chowdhury, R. & Flentje, P. Role of slope reliability analysis in landslide risk management. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 62(1), 41–46 (2003).

Johari, A., Fazeli, A. & Javadi, A. A. An investigation into application of jointly distributed random variables method in reliability assessment of rock slope stability. Comput. Geotech. 47, 42–47 (2013).

Duzgun, H. & Bhasin, R. K. Probabilistic stability evaluation of oppstadhornet rock slope, norway. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 42(5), 729–749 (2009).

Johari, A. Mehrabani Lari. System probabilistic model of rock slope stability considering correlated failure modes. Comput. Geotech. 81, 26–38 (2017).

Jimenez-rodriguez, R. & Sitar, N. Rock wedge stability analysis using system reliability methods. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 40(4), 419–427 (2007).

Johari, A. & Mehrabani, L. A. System reliability analysis of rock wedge stability considering correlated failure modes using sequential compounding method. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 82, 61–70 (2016).

Tang, H. M., Shu, Q. J. & Wang, L. F. Reliability analysis of perilous toppling rock considering seismic force direction. Appl. Math. Mech. 41(3), 319–328 (2020).

Tang, H. M., Zhang, X. C., Wang, L. F., Shen, J. G. Study on the landforms evolution of high cliff in limestone area: Taking zhenziyan cliff of Jinfo mountain in Chongqing city as an example. Journal of Chongqing Normal University(Natural Science) 35(5):54–62, (2018).

Tang, H. M., Zhou, F. C., Chen, S. & Wang, L. F. Fracture mechanism of unstable rock with double-crack control discontinuity subjected to high earthquake intensities. Applied Math. Mech. 42(6), 645–655 (2021).

Feng, Z., Li, B., Yin, Y. P. & He, K. Rockslides on limestone cliffs with sub-horizontal bedding in the southwestern calcareous area. China. Nat. Hazard Earth Sys. 14(9), 2627–2635 (2014).

Zhou, F. C., Tang, H. M., Chen, S., Wang, L. F. & Shang, C. Research on the Damage-catastrophe Mechanism of a Tower-column Unstable Rock Mass with Compressed-fracture Slumping Mode Under Multi-factor Couplings. Geotech. Geol. Eng 41, 135–151 (2022).

Hu, H. T. Research on the collapse and falling stone. J. Railway Eng. Soc. S1(1), 387–391 (2005).

Hoek, E. & Brown, E. T. The Hoek-Brown failure criterion and GSI–2018 edition. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. 3, 1–19 (2018).

Bafghi, A. R. Y. & Verdel, T. The probabilistic key-group method. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 28(9), 899–917 (2004).

Zhang, L. L., Zhang, J., Xu, Y. & Li, X. Reliability theory of geotechnical engineering (Tongji University Press, 2011).

Tang, H. M. et al. Experimental study on the dynamic acid water weakening mechanism of limestone. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 42(6), 1312–1324 (2023).

He, K., Li, B., Zhu, S. N. & Gao, Y. Experimental Study on Rock Damage Characteristic of the Key Zone for Collapsed Rock Mass. Chin. J. Underground Space Eng. 14(6), 1490–1497 (2018).

Xu, Q. Understanding the landslide monitoring and early warning: consideration to practical issues. J. Eng. Geol. 28(2), 360–374 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers and relevant editors for the constructive criticism and suggestions. In addition, the studies in this manuscript were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51378521, 51678097), the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation(Grant No. CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX0006), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023M730432), the Chongqing Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. CSTB2023NSCQ-BHX0223), the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJQN202300744).

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51378521, 51678097), the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation(Grant No. CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX0006), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023M730432), the Chongqing Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. CSTB2023NSCQ-BHX0223), the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJQN202300744). The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose, All authors contributed to the study conception and design, and this manuscript is approved by all authors for publication. All authors declare that we consulted the Guide for Authors in preparing the manuscript. And the work described was prepared in compliance with the Ethics in Publishing Policy. Te research work has not been published previously, and not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.Z. wrote the main manuscript text, X.L. and H.T. provided the idea and validated, and. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, F., Liu, X., Tang, H. et al. Analysis of the frequency–response stability and reliability of a tower-column unstable rock mass on a high and steep slope. Sci Rep 14, 20308 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70941-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70941-2

This article is cited by

-

Study on rapid identification of soil slope boulders based on natural vibration frequency

Scientific Reports (2025)