Abstract

To explore the effect of different levels of systolic blood pressure (SBP) control on new-onset chronic kidney disease in hypertension multimorbidity. The hypertensive patients with multimorbidity information were enrolled from the Kailuan Study. The isolated hypertension patients undergoing physical examination during the same period were selected in a 1:1 ratio as control. Finally, 12,897 participants were divided into six groups: Group SBP < 110 mmHg, Group 110 ≤ SBP < 120 mmHg, Group 120 ≤ SBP < 130 mmHg, Group 130 ≤ SBP < 140 mmHg, Group 140 ≤ SBP < 160 mmHg and Group SBP ≥ 160 mmHg. The outcomes were new-onset CKD, new onset proteinuria, decline in eGFR and high or very high risk of CKD. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to examine the hazard ratios (HRs) of the outcomes among SBP levels. When 110 ≤ SBP < 120 mmHg, the incidence density of new-onset CKD, new onset proteinuria and decline in eGFR were 59.54, 20.23 and 29.96 per 1000 person-years, respectively. Compared to this group, the HR (95% CI) values for the risk of new-onset CKD from Group SBP < 110 mmHg to Group SBP ≥ 160 mmHg were 1.03 (0.81–1.32), 1.04 (0.91–1.19), 1.09 (0.95–1.16), 1.16 (1.02–1.21) and 1.18 (1.04–1.24), respectively. For patients over 65 years old, the risks of outcomes were increased when SBP < 120 mmHg. The lowest HR of high or very high risk of CKD for participants with or without multimorbidity occurred when 120 ≤ SBP < 130 mmHg. The HR of new-onset CKD in hypertension multimorbidity was lowest at 110–120 mmHg. The optimal SBP level was between 120 and 130 mmHg for individuals with high or very high risk of CKD. For patients over 65 years old, the low limit of target BP is advised to be not lower than 120 mmHg.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) worldwide is about 8–16%1 and the latest data of China in 2023 was 8.2%2. Hypertension is one of the most important risk factors for CKD. Tae et al.3 found that every 10 mmHg increase of the systolic blood pressure (SBP), the risk of CKD increased 35%, but compared with 120 ≤ SBP < 130 mmHg, the CKD risk decreased about 10% when SBP < 120 mmHg. However, the SPRINT study showed that intensive blood pressure control (SBP < 120 mmHg) actually increased the risk of all-cause death in participants with SBP ≥ 160 mmHg and the 10-year risk of cardiovascular events in the Framingham Heart Study ≤ 31.3%4. The Chinese CKD cohort studies5,6,7 showed that the prevalence of hypertension in CKD was 61.02% to 71.20%. Different guidelines for the treatment of hypertension8,9,10 all set the starting treatment blood pressure level for hypertension and hypertension with CKD at SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg. However, there is no explicit indication of the low limit of target blood pressure value. Only the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines stated that 120/70mmHg was a safe lower target blood pressure and emphasized that SBP should not be less than 120 mmHg11. The guidelines, however, were based on Randomized Controlled trials (RCTs), and RCTs often exclude patients with multimorbidity. Studies have found that two thirds of hypertensive individuals have more than one multimorbidity12, such as diabetes and CKD. UKB data13 and Chinese CHAP data14 both indicate that hypertension is the most common component of multimorbidity, accounting for 76.4% in China. However, there are few studies on the effect of low limit target SBP value on new-onset CKD in hypertension multimorbidity. Therefore, we aim to use the Kailuan study to examine the effect of different levels of SBP on the new-onset CKD and provide evidence for the low limit of SBP control in hypertension multimorbidity.

Methods

Participants

The study was based on a subgroup of individuals with hypertension multimorbidity from the Kailuan Study (registration No. ChiCTRTNRC-11001489), an ongoing prospective cohort study, on the effect of different levels of SBP control on new-onset CKD in hypertension multimorbidity. The study has been followed up every 2 years since 2006. The patients with chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, stroke, CKD, and so on were followed up at chronic disease clinics. Hypertensive patients with at least one of the above chronic diseases in the Kailuan study (referred to as hypertension multimorbidity) were selected from the electronic medical record system which was used in the chronic disease clinic since 2010. Hypertensive patients with no target organ damage (negative urinary protein, no left ventricular hypertrophy on electrocardiogram) and no chronic diseases (referred to as isolated hypertension) were matched 1:1 as control. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kailuan General Hospital ([2006] Medical Ethics No. 5), all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and all participants signed the informed consent.

The participants with missing data of serum creatinine or urine protein during follow-up were excluded. We also excluded the participants with CKD at baseline and hypertensive patients who were diagnosed CKD at the same time (CKD was defined as glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and/or positive urine protein and/or renal replacement therapy (hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and renal transplantation)). Finally, 12,897 participants were included.

Data collection

Details on the self-administered questionnaires, physical examinations in the Kailuan Study could be found elsewhere15,16. We recorded in detail the medications taken by the participants by questionnaire surveys during physical examination. The diagnosis and medication use of hypertension multimorbidity were obtained through electronic records. The antihypertensive medications of hypertension multimorbidity included diuretics, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers and others that can affect the blood pressure (such as nitrates, flunarizine, nicergoline, betamethazine, propafenone, sedative, estazolam, chlorpromazine, morphine, bumetanide, terazosin, Tongxinluo, sodium and glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors). It should be noted that the traditional Chinese medicine antihypertensive preparations were excluded.

Measurement of blood pressure

A protocol for measurements of an auscultatory BP was executed by a physician using a mercury sphygmomanometer with appropriate cuff sizes. The midpoint of the right upper arm was ascertained by measuring the length from the tip of the shoulder to the tip of the elbow and dividing this length by 2. The cuff was wrapped around the straightened arm at the midpoint identified and the cuff was checked to ensure that it was neither too tight nor too loose. Three readings in sitting position were measured after the participants had 15 min of quiet rest. The average of 3 measurements was used for data analysis. Blood pressure measurement was changed to Omron HBP-1300 medical electronic sphygmomanometer at the fourth follow-up (2014–2015).

Assessment of CKD outcome

The creatine oxidase method was used to obtain results for Creatinine, the reagent was provided by Shanghai Mingdian Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The within batch CV was less than 10%, the relative range between batches was less than 10%.

eGFR was calculated using the CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) formula17. In women, eGFR = 144 × (sCr/0.7)−0.329 × 0.993Age if sCr ≤ 0.7 mg/dL and 144 × (sCr/0.7)−1.209 × 0.993Age if sCr was > 0.7 mg/dL. In men, eGFR = 144 × (sCr/0.9)−0.411 × 0.993Age if sCr was ≤ 0.9 mg/dL and 144 × (sCr/0.9)−1.209 × 0.993Age if sCr was > 0.9 mg/dL. Decline in eGFR was defined as eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

A single random midstream morning urine sample was collected from each participant.

Urinalysis was performed using a dry chemistry method and a urine sediment detection method (H12-MA urine analysis reagent strips and DIRUI N-600 urine routine detection analyzer sourced from Changchun Derui Medical Technology Co., Ltd.). Urinary protein was measured using the semi-quantitative test strip method. The results of proteinuria were recorded as negative (< 15 mg/dL), trace (15–29 mg/dL), 1 + (30–300 mg/dL), 2 + (300–1000 mg/dL) or 3+ (> 1000 mg/dL). Positive proteinuria was further defined as urine dipstick reading equal to or more than 1+.

In this study, CKD was defined and classified according to the status of eGFR and proteinuria. The participants with eGFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and/or positive proteinuria were considered as having CKD18.

We also examined the association between different SBP control levels and high or very high risk of CKD, as defined by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes 2012 recommendations18. Specifically, the eGFR categories were defined as eGFR ≥ 90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (G1), 60–89 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (G2), 45–59 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (G3a), 30–44 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (G3b), 15–29 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (G4), and < 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (G5); proteinuria categories were defined as negative and trace (< 30 mg/dL, A1), 1+ (30–300 mg/dL, A2), and ≥ 2+ (> 300 mg/dL, A3). The participants with G1–2 and A3, or G3a and A2, or G3b and A1 were defined as having high risk for CKD. The participants with G4–5 and A1, or G3b–5 and A2, or G3a–5 and A3 were defined as having very high risk for CKD.

Assessment of covariates

The fasting blood concentrations of glucose (FBG), low-and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were measured by enzymatic method using an autoanalyzer (Hitachi 747; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at the central laboratory of the Kailuan General Hospital. The specific methods used to detect other biochemical indicators in blood have been published previously15.

Definitions of the related diseases

Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, DBP ≥ 90 mmHg, or current use of antihypertensive medications.

Diabetes was defined as fasting blood glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or use of antidiabetic medications.

Hypertension multimorbidity was defined as hypertensive patients with at least one of the above chronic diseases in the Kailuan study. Isolated hypertension was defined as hypertensive patients with no target organ damage (negative urinary protein, no left ventricular hypertrophy on electrocardiogram) and no chronic diseases.

Follow-up times and determination of endpoint events

The endpoint of the outcomes was new-onset CKD, new-onset proteinuria, decline in eGFR and high or very high risk of CKD. The start point was the first diagnosis time of chronic disease for hypertension multimorbidity and the first diagnosis time of hypertension for isolated hypertension. If no adverse events occurred, the follow-up endpoint was the last health examination (December 31, 2019).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). Categorical data were presented as percentage, and continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as the median (interquartile range). Group comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance, and P < 0.05 was regarded as significant for 2-sided tests.

The propensity score matching method was used to match hypertension multimorbidity and isolated hypertension at a 1:1 ratio. Age and gender were included in the propensity score matching model and the caliper value was taken as 0.2.

The participants were divided into six groups: Group SBP < 110 mmHg, Group 110 ≤ SBP < 120 mmHg, Group 120 ≤ SBP < 130 mmHg, Group 130 ≤ SBP < 140 mmHg, Group 140 ≤ SBP < 160 mmHg and Group SBP ≥ 160 mmHg. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyze the effects of different SBP control levels on outcomes.

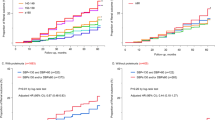

The life table method was used to calculate the cumulative incidence of different outcomes. Restricted cubic spline plots were used to analyze the dose–response relationship between SBP control level and outcomes with the nodes at the 5th, 15th, 25th, and 35th percentiles of SBP, respectively.

To explore the effect of different levels of SBP control on the risk of CKD in different groups, we also performed analysis according to age.

To test the robustness of the results, we performed two sensitivity analyses: (1) Fine-Gary competing-risk model with non-CKD deaths as competing events; (2) After hypertension patients diagnosed CKD at the same time were excluded, the Cox regression analysis was repeated.

Statement of ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kailuan General Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

With follow-up to December 31, 2019, a total of 12,897 hypertension multimorbidity (10,602 males and 2295 females) with an average age of (60.7 ± 8.8) years were enrolled. A total of 12,897 isolated hypertension (10,532 males and 2365 females) were selected.

The proportions of drinking and physical exercise were lower, the levels of BMI, TG, and FBG were higher, and the levels of eGFR, TC, LDL-C and HDL-C were lower in hypertension multimorbidity than isolated hypertension, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The baseline characteristics were shown in Supplement Table 1.

The results showed that in hypertension multimorbidity, with the increase of baseline SBP level, the levels of BMI, hs-CRP, TG gradually increased and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.01). Other data were shown in Table 1.

Incidence of CKD and Cox proportional hazards regression analysis

In hypertension multimorbidity, the incidence density of new-onset CKD, new onset proteinuria and high or very high risk of CKD were lowest when 110 ≤ SBP < 120 mmHg, which were 59.54, 20.23 and 14.15 per 1000 person-years, respectively. However, the incidence density increased when SBP < 110 mmHg. The incidence density of the above outcomes gradually increased when SBP ≥ 120 mmHg. When adjusted for relevant covariates and with Group 110 ≤ SBP < 120 mmHg as reference, analysis showed that the risk of new-onset CKD, new onset proteinuria and decline in eGFR gradually increased with the increase of blood pressure level when SBP ≥ 120 mmHg. Furthermore, the risk of new-onset CKD increased when SBP < 110 mmHg. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) was 1.03 (0.81–1.32). However, for high or very high risk of CKD, when 120 ≤ SBP < 130 mmHg was used as reference, the risk gradually increased with the increase of blood pressure level, and when SBP < 120 mmHg, the risk also increased (Table 2).

The lowest incidence density of new-onset CKD, new onset proteinuria and decline in eGFR were 22.79, 8.80, 17.58 per 1000 person-years, respectively, when SBP < 110 mmHg in isolated hypertension. When SBP ≥ 120 mmHg, the incidence density of CKD increased, but the incidence density of high or very high risk of CKD was lowest in Group 120 ≤ SBP < 130 mmHg. With Group SBP < 110 mmHg as reference, analysis showed that when SBP ≥ 110 mmHg, the risk of new-onset CKD gradually increased. For high or very high risk of CKD, compared with Group 120 ≤ SBP < 130 mmHg, the risk increased when SBP < 120 mmHg. When SBP ≥ 130 mmHg, the risk gradually increased with the increase of blood pressure level (Table 3).

Stratified analysis

We tested the interaction between SBP and age (P interaction < 0.05) and conducted stratified analysis according to age. In participants aged < 65 years, the incidence density of the outcomes were lowest in Group 110 ≤ SBP < 120 mmHg. Taking this group as reference, analysis showed that when SBP ≥ 120 mmHg, the risks of the outcomes gradually increased with the increase of blood pressure level; when SBP < 120 mmHg, the risks of new-onset CKD, new onset proteinuria, high or very high risk of CKD increased (Supplement Table 2).

In participants aged ≥ 65 years, when SBP < 120 mmHg, the incidence density of new-onset CKD, decline in eGFR and high or very high risk of CKD increased to 79.67, 46.38, 19.67 per 1000 person-years, respectively. However, the incidence density of new-onset proteinuria was lowest in Group 120 ≤ SBP < 130 mmHg. Taking this group as reference, analysis showed that when SBP ≥ 130 mmHg, the risk of new-onset CKD and new onset proteinuria increased gradually; when SBP < 120 mmHg, the risk of new-onset CKD increased. The HR and 95% CI was 1.36 (1.08–1.72). However, for high or very high risk of CKD, the incidence density was lowest in Group 130 ≤ SBP < 140 mmHg. Taking this group as reference, when SBP ≥ 130 mmHg, the risk of incidence gradually increased with the increase of blood pressure level (Supplement Table 3).

Restricted cubic spline analysis

The results showed that there was no linear dose–response relationship between SBP and the outcomes in hypertension multimorbidity after adjusting for factors such as age and gender (P trend > 0.05, P non-linear > 0.05). (As shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

Discussion

In this study, diabetes was the most common multimorbidity (54.97%). The prevalence of CKD was 60.5 per 1000 person-years in hypertension multimorbidity and 32.58 per 1000 person-years in isolated hypertension. Cohort study by Wang et al.19 showed that the incidence density of CKD was higher when hypertension was combined with diabetes than isolated hypertension, which supported our results. Wang et al.20 found that the incidence of CKD in elderly patients with hypertension and diabetes was 18.10%, which was higher than in patients without hypertension (13.60%). Seid et al.21 found that the incidence of CKD in patients with hypertension and diabetes was 3.52 times higher than that in patients without hypertension and diabetes. Pepine et al.22 also found that the risk of cardiovascular events was increased in hypertension multimorbidity, such as coronary heart disease and diabetes, which indirectly supported our findings.

We also found that the incidence density of CKD was lowest in Group 110 ≤ SBP < 120 mmHg in hypertension multimorbidity. This finding was similar to the SPRINT study23, which showed, compared to standard BP control (SBP < 140 mmHg), intensive BP control (SBP < 120 mmHg) could reduce the composite CVD outcome by 25% and provided additional benefit for patients with CKD. However, this study failed to provide a lower limit target of SBP and our study filled this knowledge gap.

We also found that different SBP levels were associated with the risk of CKD. The risk of new-onset CKD was lowest in Group 110 ≤ SBP < 120 mmHg in hypertension multimorbidity. The meta-analysis showed that intensive anti-hypertensive treatment (blood pressure < 125/73 mmHg) was significantly associated with a lower risk of developing macroalbuminuria than the blood pressure level of 134/79 mmHg in patients with type 2 diabetes24. According to CARDIA Study, the change in kidney function among young adults (18–30 years) who did not have CKD or hypertension was 0.52 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the first decade of follow-up25. All above results supported our findings. However, the ACCORD study26 found that intensive blood pressure control (mean SBP level of 119.3 mmHg) failed to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular composite outcomes in patients with hypertension and diabetes compared with the mean SBP level of 133.5 mmHg, but increased the corresponding side effects. This may be due to the fact that the HbA1c target was too low, or the intensive-treatment group used more oral agents and therefore had a higher risk of severe hypoglycemic events. Michal Bohm’s study27 also supported that blood pressure should not be lower than 120/70 mmHg in patients with hypertension and diabetes. All these data indicated that we should pay attention to multimorbidity.

For high or very high risk of CKD, the risk of CKD was lowest in Group 120 ≤ SBP < 130 mmHg with multimorbidity or not. Meta-analysis showed that blood pressure level of 125/73 mmHg was associated with a lower risk of composite kidney disease than 134/79 mmHg24. Another meta-analysis also found that in high-risk population with SBP < 140 mmHg, intensifying blood pressure control yield even greater benefits28. Therefore, for high or very high risk of CKD, regardless of multimorbidity, the range of blood pressure control could be appropriately relaxed.

We further stratified by age and found that for those aged < 65 years the risk of CKD was lowest in Group 110 ≤ SBP < 120 mmHg, whereas for those aged ≥ 65 years the risk of CKD was lowest in Group 120 ≤ SBP < 130 mmHg. VALISH Study found that the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality were lowest with SBP between 130–140 mmHg among patients aged 70–84 years with isolated systolic hypertension29. Meta analysis showed that lowering blood pressure to 150/80 mmHg in patients ≥ 65 years of age reduced cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality30. But none of the above studies provided low limit target of blood pressure, and our study filled the gap.

We also found that at the same level of SBP, the risk of the outcomes in hypertension multimorbidity were higher than that in isolated hypertension (Supplement Table 4).This finding was consistent with the results reported by Michael Bom27, who found that both the relative and absolute risks of hypertension combined with diabetes were higher than those of hypertension alone. This also suggested that patients with hypertension multimorbidity should not only control blood pressure, but also treat multimorbidity positively.

Hypertension can cause renal damage and renal damage can exacerbate hypertension. The classical pathogenesis of hypertensive CKD mainly includes water and sodium retention, increased activity of renin-angiotensin system31, increased synthesis of endothelin32. The mechanism is complex for hypertension multimorbidity33. Hypertension combined with diabetes might promote renal injury by increasing intraglomerular pressure, and activation of hypertensive mechanical transduction signals may amplify the metabolic effects of diabetes, leading to renal cell damage through a vicious cycle of impaired Ca2+ homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction. Moreover, hypertension could lead to renal organic damage34. However, for high or very high risk of CKD, the higher level of proteinuria lead to faster decrease of glomerular filtration rate35,36,37 and the renal blood flow. Therefore, the control level of SBP should be appropriately relaxed to prevent the aggravation of renal ischemia for high or very high risk of CKD.

Our cohort was large, basically stable, with a long duration of follow-up. Our observation period was 12 years, with a mean follow-up of 7 years, which was longer than most RCTs, so the results could be extended to clinical practice. But it also had several limitations. Firstly, most of the participants were male coal miners living in northern China. Therefore, women were underrepresented, and the findings may not be directly generalizable to other populations. Secondly, given the effect of blood-pressure dynamics on adverse outcomes during follow-up, we performed time-varying Cox regression analyses with follow-up of SBP every 2 years, and the results were consistent with those of the main model. In addition, the medication information of isolated hypertension was obtained from questionnaires, which may be underreported due to memory bias. At the same time, data on medication frequency were not available, but we minimized these errors by collecting information from multiple questionnaires. Finally, the number of multimorbidity reached 34, but diabetes and coronary heart disease were the main multimorbidity, which was consistent with Quiñones et al.38 study and the development trend of multimorbidity. More comprehensive data should be collected.

Conclusions

In conclusion, when SBP was controlled between 110–120 mmHg, the risk of new on-set CKD was lowest among hypertension multimorbidity, and when SBP < 110 mmHg the risk of new-onset CKD was lowest in isolated hypertension. The optimal SBP control level was between 120 and 130 mmHg for individuals with high or very high risk of CKD. For patients aged over 65 years old, the low limit of target BP is advised to be not lower than 120 mmHg.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files.

References

GBDCKD Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 395(10225), 709–733 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: Results from the sixth china chronic disease and risk factor surveillance. JAMA Intern. Med. 183(4), 298–310 (2023).

Chang, T. I. et al. Associations of systolic blood pressure with incident CKD G3–G5: A cohort study of South Korean adults. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 76(2), 224–232 (2020).

Jaeger, B. C. et al. Longer-term all-cause and cardiovascular mortality with intensive blood pressure control: A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 7(11), 1138–1146 (2022).

Liu, B. et al. Utilization of antihypertensive drugs among chronic kidney disease patients: Results from the Chinese cohort study of chronic kidney disease (C-STRIDE). J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 22(1), 57–64 (2020).

Zheng, Y. et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the non-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients. Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 126(12), 2276–2280 (2013).

Zhang, W. et al. A nationwide cross-sectional survey on prevalence, management and pharmacoepidemiology patterns on hypertension in Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 38768 (2016).

Chinese Society of Nephrology. Guidelines for hypertension management in patients with chronic kidney disease in China (2023). Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 39(1), 48–80 (2023).

Al-Makki, A. et al. Hypertension pharmacological treatment in adults: A World Health Organization guideline executive summary. Hypertension 79(1), 293–301 (2022).

Frame, A. A. & Wainford, R. D. Renal sodium handling and sodium sensitivity. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 36(2), 117–131 (2017).

Williams, B. et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J. Hypertens. 36(10), 1953–2041 (2018).

Brilleman, S. L. et al. Implications of comorbidity for primary care costs in the UK: A retrospective observational study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 63(609), e274-282 (2013).

Zemedikun, D. T., Gray, L. J., Khunti, K., Davies, M. J. & Dhalwani, N. N. Patterns of multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adults: An analysis of the UK Biobank data. Mayo Clin. Proc. 93(7), 857–866 (2018).

Wang, R. et al. Prevalence and patterns of chronic disease pairs and multimorbidity among older chinese adults living in a rural area. PLoS One 10(9), e0138521 (2015).

Shou-Ling, W. U. et al. Risk prediction of high sensitivity c-reactive protein on the incidence of hypertension in prehypertensive population. Chin. J. Hypertens. 18(04), 390–394 (2010).

Zhang, Q. et al. Ideal cardiovascular health metrics and the risks of ischemic and intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke. Stroke 44(9), 2451–2456 (2013).

Rognant, N., Lemoine, S., Laville, M., Hadj-Aissa, A. & Dubourg, L. Performance of the chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 34(6), 1320–1322 (2011).

Stevens, P. E., Levin, A., Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: Synopsis of the kidney disease: Improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med. 158(11), 825–830 (2013).

Wang, M. et al. The effects of hypertension and diabetes on new-onset chronic kidney disease: A prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 22(1), 39–46 (2020).

Zhi-Jun, W., Jian-Zhi, Z. & Shou-Ling, W. U. Risk factors for hypertension in elderly diabetes mellitus patients and their follow-up. Chin. J. Geriatr. Heart Brain Vessel Dis. 15(02), 151–154 (2013).

Seid, M. A. et al. Microvascular complications and its predictors among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at Dessie town hospitals, Ethiopia. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 13(1), 86 (2021).

Pepine, C. J. et al. Predictors of adverse outcome among patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47(3), 547–551 (2006).

Group SR et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N. Engl. J. Med. 373(22), 2103–2116 (2015).

Ioannidou, E. et al. Effect of more versus less intensive blood pressure control on cardiovascular, renal and mortality outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 17(6), 102782 (2023).

Ku, E. et al. Changes in blood pressure during young adulthood and subsequent kidney function decline: Findings from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adulthood (CARDIA) Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 72(2), 243–250 (2018).

ACCORD Study Group et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 362(17), 1575–1585 (2010).

Bohm, M. et al. Cardiovascular outcomes and achieved blood pressure in patients with and without diabetes at high cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 40(25), 2032–2043 (2019).

Xie, X. et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 387(10017), 435–443 (2016).

Yano, Y. et al. On-treatment blood pressure and cardiovascular outcomes in older adults with isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertension 69(2), 220–227 (2017).

Briasoulis, A., Agarwal, V., Tousoulis, D. & Stefanadis, C. Effects of antihypertensive treatment in patients over 65 years of age: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. Heart 100(4), 317–323 (2014).

Tornel, J., Madrid, M. I., Garcia-Salom, M., Wirth, K. J. & Fenoy, F. J. Role of kinins in the control of renal papillary blood flow, pressure natriuresis, and arterial pressure. Circ. Res. 86(5), 589–595 (2000).

Zoccali, C., Mallamaci, F. & Tripepi, G. Novel cardiovascular risk factors in end-stage renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15(Suppl 1), S77–S80 (2004).

Wang, Z., do Carmo, J. M., da Silva, A. A., Fu, Y. & Hall, J. E. Mechanisms of synergistic interactions of diabetes and hypertension in chronic kidney disease: Role of mitochondrial dysfunction and ER stress. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 22(2), 15 (2020).

Rianto, F., Hoang, T., Revoori, R. & Sparks, M. A. Angiotensin receptors in the kidney and vasculature in hypertension and kidney disease. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 529, 111259 (2021).

Hallan, S. I. et al. Combining GFR and albuminuria to classify CKD improves prediction of ESRD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20(5), 1069–1077 (2009).

Iimori, S. et al. Prognosis of chronic kidney disease with normal-range proteinuria: The CKD-ROUTE study. PLoS One 13(1), e0190493 (2018).

Gansevoort, R. T. & de Jong, P. E. The case for using albuminuria in staging chronic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20(3), 465–468 (2009).

Quinones, A. R. et al. Prevalent multimorbidity combinations among middle-aged and older adults seen in community health centers. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 37(14), 3545–3553 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of the Kailuan study and the laboratory staff of the Department of Cardiology of Kailuan Hospital for their contributions to the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yu and Li searched the literature, conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. Wang and Wu organized and supervised the study, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. Other members collected and analyzed the data. Li and Wu are the guarantors and take full responsibility for the work as a whole, including the study design, access to data, and the decision to submit and publish the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Y., Wang, D., Guo, Z. et al. The effect of different levels of systolic blood pressure control on new-onset chronic kidney disease in hypertension multimorbidity. Sci Rep 14, 19858 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71019-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71019-9