Abstract

The morphological characteristics of the foot arch and the plantar soft tissue thickness are pivotal in assessing foot health, which is associated with various foot and ankle pathologies. By applying deep learning image segmentation techniques to lateral weight-bearing X-ray images, this study investigates the correlation between foot arch morphology (FAM) and plantar soft tissue thickness (PSTT), examining influences of age and sex. Specifically, we use the DeepLab V3+ network model to accurately delineate the boundaries of the first metatarsal, talus, calcaneus, navicular bones, and overall foot, enabling rapid and automated measurements of FAM and PSTT. A retrospective dataset containing 1497 X-ray images is analyzed to explore associations between FAM, PSTT, and various demographic factors. Our findings contribute novel insights into foot morphology, offering robust tools for clinical assessments and interventions. The enhanced detection and diagnostic capabilities provided by precise data support facilitate population-based studies and the leveraging of big data in clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In daily activities, the foot, as a biomechanical structure, bears the body weight and plays a crucial role in human locomotion. When standing or walking, the ground reaction force applied to the foot can reach 1.2 times body weight, escalating to 2.5 times during more strenuous activities like running and jumping, the distribution and magnitude of the plantar pressure significantly influence foot health1. The human foot's bony structure, ligaments, and plantar soft tissues undergo elastic deformation due to inherent skeletal morphology differences and external forces during movement. This deformation collectively determines the distribution of plantar pressure. Different regions accumulate varying stress over time, resulting in distinct deformations, reflected specifically in changes in foot arch morphology (FAM) and plantar soft tissue thickness (PSTT)2. Consequently, alterations in FAM and PSTT further impact the force direction and balance, thereby affecting foot health3. Therefore, the characteristics of FAM and PSTT are two vital factors extensively attended to by clinicians.

The FAM is defined by multiple indices and serves as a key indicator in clinical evaluation of various foot pathologies. For instance, the diagnosis of flatfoot and high-arch feet primarily relies on foot arch height4, which is determined by the curvature of the longitudinal arch and transverse arch, and influences foot stability, shock absorption, and propulsion efficiency5. Radiographic imaging is usually used to evaluate the foot morphology under weight-bearing conditions when evaluating foot deformity clinically6. Particularly, weight-bearing lateral X-rays of the foot are considered the gold standard for diagnosing progressive collapsing foot deformity7 and for assessing medial longitudinal arch characteristics8.

The PST is subjected to the highest mechanical loads in the human body and has developed unique properties over time to accommodate these demands. These include wear resistance, pressure tolerance, and the limitation of interlayer displacement. Functionally, the PST supports weight, absorbs and cushions impacts from the ground, and maintains body balance and stability9,10. It consists of complex structures such as skin, adipocytes, fascial layers, and muscles11. Variations in PSTT can influence the distribution of plantar pressure and the overall biomechanical behavior of the foot. Clinical observations and statistical data indicate that PST degeneration is linked to many common foot and ankle disorders, particularly in elder adults. Such degeneration may lead to pain and contribute to conditions like metatarsalgia, plantar fasciitis, hallux valgus, and complications in diabetic foot conditions12,13,14,15,16,17,18.

While FAM and PSTT are common indicators for evaluating foot health clinically, the evaluation methods exhibit subjectivity and lack standardized criteria. In clinical practice, doctors typically manually annotate and measure radiological imaging results to assess FAM, focusing on parameters such as the calcaneal pitch angle (CPA) and the talo-first metatarsal angle (TMA or Meary’s angle) to diagnose conditions like flatfoot and high arches19. However, these angles can be measured using approximately four to six different methods20, and there is no standardized approach for defining and measuring arch height. Additionally, these manual measurements are time-consuming for practitioners.

Worse still, detecting variations in PSTT presents significant challenges due to its individualized nature, influenced by age, sex, diseases, and lifestyle factors21,22. Ultrasound has emerged as the primary method for assessing PSTT due to advancements in technology23,24,25. Additionally, the development of computer technology and advanced medical imaging techniques has facilitated the use of visual image processing, including deep learning and artificial intelligence, in foot medical imaging26,27,28. Despite these advancements, there remains a gap in analyzing the correlation between PSTT and factors such as sex, age, and footwear habits, particularly in studies utilizing large datasets for comprehensive statistical analysis. Moreover, the scarcity of medical data has hindered investigations into the correlation between foot skeletal structure and PSTT across large data volumes. Consequently, prior research has yielded inconsistent and inconclusive results regarding the relationship between FAM and PSTT, with limited examination of the impact of demographic factors. Exploring these associations is essential for precise and efficient foot health assessment, enhancing understanding of foot biomechanics, aiding in disease prevention and rehabilitation, and informing footwear and orthotic design.

Methods

To address the aforementioned challenges, our study amassed a substantial dataset of weight-bearing lateral foot X-ray images, a type for which there is currently no publicly available dataset. A set of 1497 images is retrospectively collected from the foot and ankle database of Huashan Hospital (Shanghai, China) spanning the last decade, with the personal info anonymized and ethic review approved. Utilizing deep learning image segmentation techniques, we preprocessed these images by adjusting grayscale, removing noise, and normalizing the images, enhancing the model's robustness, stability, and accuracy29. We then trained a deep neural network to perform precise segmentation of the first metatarsal (FM), talus (TA), calcaneus (CA), navicular (NAVI) bones, as well as the overall foot boundary. This approach enabled automated, standardized, and batch processing for precise computations of FAM and PSTT, thereby yielding significant time and cost efficiencies.

Our study focuses on analyzing the homogeneity and heterogeneity within large datasets, employing data-driven methods to identify patterns of similarity and dissimilarity across population groups. We specifically explored the correlation between FAM and PSTT among diverse demographic groups. Section “Methods” details the methodology, including data sourcing, dataset composition and preprocessing, development of deep learning image segmentation models, and evaluation metrics for FAM and PSTT. Section “Results” presents the results, elaborating on the performance of the segmentation models, data outcomes for FAM and PSTT, and the correlation analyses across different demographic groups. Section “Discussion” discusses the methodologies, results, and hypotheses, concluding with a summary and future outlook of the research. The overall study workflow is depicted in Fig. 1.

Human ethical statements

We confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. We confirm that all experimental protocols were approved by The Ethical Review Committee of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University (HIRB). This is a retrospective study, all the images are provided anonymously, and this paper only reports general statistical results over the dataset, therefore the informed consent was waived. This waiver was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fudan University, ensuring compliance with ethical standards for the use of pre-existing data where participant identification is not disclosed.

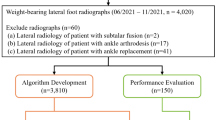

Dataset

The application of deep learning for image detection and segmentation requires a substantial dataset. Due to the unavailability of public X-ray image datasets, we undertook a retrospective data collection to facilitate efficient and cost-effective research. We compiled 1497 weight-bearing lateral full foot X-ray images from Huashan Hospital’s foot and ankle imaging database, spanning from 2013 to 2022, involving 1098 patients. The data, stored in DICOM file format30,31, includes demographic details such as sex, age, and imaging timestamps. All data samples were anonymized during processing and subsequent research phases to ensure privacy. Additionally, to account for the developmental stage of children’s skeletons, we excluded samples from individuals under the age of 14 years. The collection process also involved manual screening by foot and ankle surgeons to exclude images from patients with skeletal or soft tissue foot defects, a history of foot ulcers, neurological joint diseases, post-foot surgery conditions, and those unable to walk independently.

The X-ray images were sourced from medical imaging devices produced by several manufacturers, including GE, Canon, Philips, CARESTREAM, and KODAK. These devices capture images with an average pixel spacing of approximately 0.14 mm/pixel. The X-rays are collected as grayscale images with a depth of 16 bits, and the resolution of these collected images ranges from 1010 to 4260 pixels in length (columns) and 965–4259 pixels in width (rows). For visualizing and processing the X-ray images, we employed the PyDicom library, a medical image processing tool, to parse DICOM files and convert the X-ray grayscale images into JPG format for easier handling32. Table 1 presents the basic information of these data samples. In this study, each X-ray image is treated as an individual data sample. This includes both left and right foot X-ray images of the same patient and multiple images taken from the same patient over the past decade, without filtering for duplicate individuals in the dataset.

Image preprocessing

From the dataset, 220 images were randomly selected and divided into training, validation, and testing sets, with 180, 20, and 20 images respectively. Under the supervision of foot and ankle surgeons, these images were manually annotated for precise boundary delineation of the entire foot and the four bone structures: FM, TA, CA, and NAVI, using the LabelMe library. These annotations served as the ground truth for model training33. Once the model’s accuracy and generalization were confirmed, it was applied to all sampled images to automatically calculate metrics related to FAM and PSTT. This facilitated large-scale data analysis to investigate the factors influencing these measurements.

Additionally, to enhance the robustness and generalization capability of the model, we employed the Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) algorithm for contrast enhancement34, and converted the 16-bit X-ray image into 8-bit images with sufficient contrast. Subsequently, image normalization is performed to reduce differences in brightness and contrast, mitigating the model’s susceptibility to outliers or extreme pixel values. Next, in order to reduce computational complexity and memory usage, we utilized the bilinear interpolation method35 for resizing the original images to a unified size of 384 × 576 pixels as input for the model, and ensured that the key semantic information in the images was preserved. Figure 2 illustrates an example weight-bearing lateral foot X-ray image.

A weight-bearing lateral foot X-ray image and manually annotated ground truth: (a) the original grayscale image parsed from the DICOM file serves as the input to the model; (b) the manual labeling results using the Labelme library, stored as a JSON file; (c)–(g) the boundaries of the entire foot, FM, TA, CA and NAVI bones obtained from parsing the JSON file. Here, for visual clarity, these label boundaries are overlaid on the original image for visualization, though each labeled image is actually a binary black-and-white image; (h) visualization of various labeled images with different pixel values overlaid on one image.

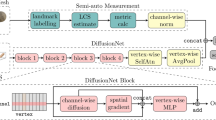

Deep learning image segmentation model

In our selection of deep learning network models, for the task of calcaneus (CA) segmentation, we evaluated four widely used models in medical image segmentation: FCN36, U-Net37, SegNet38, and DeepLab V3+ 39. Due to the optimal performance of the DeepLab V3+ model, we chose it for automatic image segmentation. To enhance robustness and accuracy, we constructed five independent DeepLab V3+ segmentation models, one for the entire foot boundary and one for each of the four bone boundaries (FM, TA, CA, NAVI). Each model was trained separately to optimize parameters. The input image dimensions were standardized to 384 × 576 pixels, and outputs were binarized using the sigmoid function 40. To ensure reproducibility, all training runs were conducted with fixed seed settings. PyTorch was used for model construction and training, with parameters as follows: Adam optimizer41, learning rate is set to 10–4, batch size is set to 4, epoch is set to 20. The environment and versions are macOS Ventura 13.2.1, 4-cores CPU, 16 GB RAM, PyTorch version 1.8. For the loss function and evaluation metrics, we selected the Dice coefficient and Intersection over Union (IoU). The Dice coefficient is particularly sensitive to small targets, making it ideal for precise segmentation of smaller anatomical structures, while IoU is well-suited for large target detection and segmentation tasks. Therefore, we utilized Dice loss for training to optimize our model's ability to detect small variations, and employed IoU as the evaluation metric to assess the overall accuracy and integrity of the segmentation across larger areas42.

Additionally, in the test set, in rare extreme cases where X-ray images contained high-intensity artifacts, the model might misclassify noise and contamination during segmentation. Therefore, post-processing was applied to the segmentation masks using the DBSCAN algorithm for clustering43. This step retained the largest clustered area as the target region and set the values of smaller misclassified noise regions to 0, eliminating interference in subsequent tasks such as extracting bone axes and calculating PSTT.

Calculation and evaluation of FAM and PSTT indicators

In this study, we focused on three primary descriptors of FAM as advised by foot and ankle surgeons: the angle between the axes of the first metatarsal and the talus (“angle-fm-ta”), the inclination of the calcaneus axis relative to the plantar surface (“angle-ca-plantar”), and the longitudinal arch height (LAH). Additionally, we measured PSTT at the forefoot and rearfoot regions.

To calculate the “angle-fm-ta” and “angle-ca-plantar” in weight-bearing lateral foot X-ray images, we first applied the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) algorithm44 to determine the principal axes of the segmented FM, TA, and CA bones. We then calculated the angle between the principal axes of the FM and TA to determine the “angle-fm-ta.” This method mirrors the standardized manual angle measurements performed by surgeons using X-ray reading software, reducing subjective variability. The “angle-ca-plantar” was defined as the angle between the main axis of the CA (which derived by PCA) and the horizontal plane, as suggested by surgeons.

For the calculation of LAH, we identified the center of the NAVI bone based on the PCA algorithm and defined it as the distance from the NAVI bone center to the median of the PST boundary points on the forefoot and rearfoot. Figure 3 displays schematic diagrams of these measurements for both the left (a) and right feet (b). Notably, here we stipulated that the “angle-fm-ta” is the angle between the FM axis and the TA axis, potentially resulting in angles greater than 180°.

We also measured PSTT by calculating the distance from the lowest boundary point of the FM to the foot’s lower border directly beneath it, denoted as the forefoot PSTT (arrow A in Fig. 3). Similarly, the rearfoot PSTT was measured from the lowest point of the CA to the foot boundary beneath it (arrow B in Fig. 3).

For comparative analysis, we calculated the foot length (FL), defined as the distance between the outermost points of the toe and heel, marked by a red line in Fig. 3. The LAH and PSTT values were then normalized by dividing by the FL, resulting in normalized indicators: normalized LAH, normalized forefoot PSTT, and normalized rearfoot PSTT.

Results

Image segmentation model results

In the model selection stage, the performance of four different models is compared and summarized in Table 2. Among these, DeepLab V3+ demonstrated superior performance, particularly in detailed boundary segmentation and generalization capabilities.

Table 3 summarizes the performance of five segmentation model on the training, validation, and test set respectively. It is observed that among the five segmentation tasks, the performance of the entire foot segmentation model is the best. Besides, all models demonstrate good performance and generalization, thereby avoiding the issue of overfitting.

Figure 4 displays the automated segmentation results from a randomly selected image in the testing set, detailing outcomes for the entire foot boundary and the FM, TA, CA, and NAVI bone regions (Fig. 4b–f). The results demonstrate precise delineation of the foot outline and CA boundaries, underscoring the model’s efficacy. However, minor discrepancies are observed in the segmentation of the FM, TA, and NAVI bones, due to the complexities involved in segmenting these intricate structures. These challenges, akin to those encountered in manual annotation by experienced surgeons, are demanding and time-intensive. Nonetheless, the overall model performance is satisfactory. Surgeons manually reviewed and validated the results, noting a high concordance with actual bone boundaries. These discrepancies were considered negligible, affirming the model’s utility and accuracy for FAM and PSTT analyses.

Furthermore, Figure 5 demonstrates the comparative effectiveness of using the DBSCAN method for handling outlier data with artifacts. It is visually apparent that this method effectively rectifies errors in the DeepLabV3+ model.

Result of FAM analysis

Distribution of FAM characteristic indicators

Figure 6a–c show the statistical histogram of the angle-fm-ta, angle-ca-plantar, and the normalized LAH respectively, obtained through automated calculations via image segmentation and PCA. It is evident from the figures that the distribution of the angle-fm-ta is mainly concentrated around 180° (182.151° ± 11.433°), which is consistent with the normal FAM in medicine. The angle-ca-plantar is mainly distributed around 12° (11.941° ± 6.169°), but a small number of negative values are observed, which were subsequently diagnosed by orthopedic surgeons as cases of flatfoot during further analysis. The mean and standard deviation of the normalized LAH are calculated as 0.214 times FL and 0.034 times FL, respectively. Analysis of the coefficient of variation (angle-fm-ta CV = 0.063, angle-ca-plantar CV = 0.517, normalized LAH CV = 0.160) for the three metrics indicates that the angle-fm-ta exhibits the highest stability across various samples.

Interrelationships among FAM characteristic indicators

As shown in Fig. 7, there is a strong correlation among the three characteristic indicators of FAM. The normalized LAH exhibits a negative correlation with the angle-fm-ta (The Spearman correlation coefficient: r = − 0.9 and the p-value is 0), while showing a positive correlation with the angle-ca-plantar (r = 0.71, p = 0). Subjects with larger angle-fm-ta tend to have smaller angle-ca-plantar, and may even become negative in some cases. Additionally, their normalized LAH tends to be lower. Such characteristics are associated with flatfoot conditions.

Relationship between FAM indicators and sex

Figure 8 illustrates the variations in the distributions of angle-fm-ta, angle-ca-plantar, and normalized LAH, highlighting the influence of sex on these metrics. The data shows that the angle-fm-ta is generally higher in females than in males. Additionally, there is a strong correlation among these three indicators; correspondingly, the angle-ca-plantar and normalized LAH are both observed to be smaller in females compared to males. This pattern underscores the impact of sex-specific anatomical differences on these foot arch morphology metrics.

Relationship between FAM and age

We categorized the age distribution of all collected samples into eight groups, ranging from 14 to 90 years old, with the following brackets: [14–40], [41–50], [51–60], [61–70], [71–80], and [81–90]. This organization was made after excluding samples from individuals under the age of 14. Figure 9a–c displays the box plots for the distribution of three evaluation indicators of FAM across these age groups. The plots indicate that there is no significant correlation between FAM and age, as the data distribution shows minimal variation among the different age categories.

Result of PSTT analysis

Relationship between PSTT and sex

Table 4 presents the distribution of PSTT across all data samples, categorized by sex, displaying the mean thickness for both the forefoot and rearfoot. There is a discernible difference in PSTT between these regions, averaging approximately 0.5 mm. This specific measurement facilitates comparisons between PSTT beneath the FM and CA. Such variability underscores the need for further exploration of regional PSTT differences within the foot. Additionally, Fig. 10 illustrates the normalized distribution of forefoot and rearfoot PSTT by sex, indicating that PSTT is generally thicker in males than in females, particularly in the forefoot.

Relationship between PSTT indicators and age

Table 5 summarizes the results of PSTT grouped by age. Due to the limitation of retrospective data collection, it is not feasible to subjectively intervene in achieving a balanced distribution of sample sizes within each age group.

Figure 11a and b depict how normalized forefoot and rearfoot PSTT vary with age across groups, showing an initial increase followed by a decrease in PSTT with advancing age. This pattern is influenced by developmental factors in adolescents aged [14–20] and is potentially skewed by the small sample size of 18 in the [81–90] age group, which may introduce outliers. Excluding these groups, the data show a more pronounced decrease in PSTT among older adults, indicating thinner plantar soft tissues compared to middle-aged groups, especially in the heel area. Additionally, Fig. 12 illustrates the impact of sex on PSTT across age groups, with males generally exhibiting thicker PSTT than females. This trend, consistent across most age groups, underscores the complex interaction between age and sex in influencing PSTT.

Correlation between FAM and PSTT

The foot arch and plantar soft tissue play crucial roles in supporting body weight, absorbing pressure, and cushioning impact forces, with their interactions leading to changes in FAM and PSTT. Based on clinical insights, we explored the associations between LAH and PSTT, the correlation between the angle-fm-ta and forefoot degeneration, and the relationship between the angle-ca-plantar and rearfoot.

Figure 13 illustrates the data distribution and a linear regression analysis of the relationship between LAH and PSTT across different sexes, using a comprehensive dataset. The Spearman correlation coefficient for males is 0.472 (p-value < 0.001), and for females, it is 0.488 (p-value < 0.001). A unified linear regression line (brown line) representing the entire sample indicates a correlation coefficient of 0.487 (p-value < 0.001), demonstrating the significant influence of arch height on PSTT across sexes. It can be seen that the smaller the value of normalized LAH, the smaller the value of normalized Mean-PSTT, indicating that individuals with lower arches tend to have relatively thinner PST.

Regarding the study relationship between the angle-fm-ta and forefoot PST degeneration, the correlation grouped by sex are illustrated in Fig. 14. The bold blue line represents the overall data correlation. The overall trends for either males or females show a negative correlation (Males: r = − 0.352, p-value = 0.0; Females: r = − 0.351, p-value = 0.0; Overall: r = − 0.363, p-value = 0.0). For samples with larger angle-fm-ta (greater than 180°), indicating with a flatter foot arch, there is a greater impact on the degeneration of the forefoot PST, resulting in a smaller forefoot PSTT.

Subsequently, we examined the relationship between angle-ca-plantar and rearfoot PSTT. The analysis indicated a correlation between the angle-ca-plantar and the variation in thickness between forefoot and rearfoot PSTT, denoted as “ca-fm PSTT diff.” As shown in Fig. 15, there is a negative correlation between angle-ca-plantar and this thickness differential, suggesting that a larger angle-ca-plantar increases the load on rearfoot tissues, accelerating their degeneration relative to the forefoot and resulting in less disparity in tissue thickness (Males: r = − 0.376; Females: r = − 0.354; Overall: r = − 0.375; all p-values < 0.001).

Statistical analyses were performed on different age groups to evaluate the impact of sex on three types of correlations, as depicted in Figs. 16, 17, and 18. Again, the [14–20] and [81–90] age group was excluded. Apart from a limited number of male samples in the [71–80] age group, the correlation trends across the other groups align closely with the overall data patterns previously analyzed, showing minimal performance discrepancies. Spearman correlation coefficients for each group are detailed in the corresponding figures.

Discussion

In this study, the absence of publicly available datasets necessitated manual annotation to construct a dataset for training deep learning models. Manual annotation, particularly of foot and ankle structures, is both costly and labor-intensive. A total of 220 images were selected randomly for the segmentation models, based on the high costs associated with annotation and the satisfactory performance of 180 training images. Despite random sampling, a small proportion of images with noise artifacts were excluded from model training, potentially impacting output accuracy and necessitating post-processing corrections using methods like DBSCAN.

Five DeepLab V3+ segmentation models were developed to address various complexities associated with segmenting the entire foot boundary and specific bone regions (FM, TA, CA, NAVI). The segmentation of individual bones was challenging due to their interconnected and overlapping features in lateral X-ray images. Manual annotation also presented difficulties due to the three-dimensional skeletal structures being projected onto a two-dimensional plane, particularly for the talus where varus and valgus deformities cause overlaps. The selection of which part to define as the boundary of the talus significantly impacts the calculation of its main axis. After extensive experimentation with various labeling methods, foot and ankle surgeons determined that the most accurate approach is to select the lower boundary of the projection of the talar roof as the upper edge, and the talocalcaneal articular surface as the lower edge, ignoring any lateral protrusions. This method ensures that the main axis results extracted by PCA align more closely with the actual anatomical structure. Despite these complexities, the models generally produced satisfactory results.

Another aspect that merits discussion involves the evaluation indicators for FAM and PSTT. Clinically, the talus-first metatarsal angle (also known as Meary’s angle) in a lateral standing position typically sees the inferior talus oblique line extending through and being collinear with the first metatarsal axis, forming an angle of 0°, or slightly lower than the first metatarsal axis. The definition of when the talus-first metatarsal angle is positive or negative remains controversial, however in this work, the angle is specified as 180° for the collinear case.

This study also scrutinizes evaluation indicators for FAM and PSTT. The talus-first metatarsal angle (Meary’s angle), observed when the inferior talus oblique line is collinear with the first metatarsal axis, is controversially defined but specified as 180° for collinearity in this work. Clinically, FAM assessments often focus more on the inclination of the calcaneus along its superior oblique line rather than the inclination angle of the calcaneus axis (angle-ca-plantar). For clarity and simplicity in our analysis, and to better understand the trends and correlations with various factors, we opted to use the calcaneal axis inclination angle as our evaluation index. The superior calcaneal oblique line is typically drawn between two points: the first along the inferior surface of the calcaneocuboid joint and the second along the anteroinferior aspect of the medial tubercle.

Regarding PSTT, while the forefoot primarily supports balance, the rearfoot aids propulsion and stability45. The load-bearing and degenerative conditions of PST thus vary across different foot regions. In this study, PSTT was specifically defined for the forefoot and rearfoot in lateral X-rays. Future research will necessitate a more refined differentiation of plantar soft tissue regions to explore the anatomical and functional disparities further.

Lastly, challenges in data collection due to the retrospective approach limited the control over variables such as sex and age and restricted access to extensive clinical data, impacting the ability to fully account for intergroup differences. Future research will benefit from a larger and more diverse dataset to enable more comprehensive conclusions. Additionally, further single-variable experiments are required to validate current findings and clarify the influences of critical variables such as weight, BMI, footwear habits, activity levels, and medical history on PSTT and other related variables.

Conclusion

This study employed a retrospective collection of weight-bearing lateral foot X-ray images spanning a decade to develop a deep learning segmentation model, specifically DeepLabV3+, for the automated and accurate extraction of FAM and PSTT. The model was trained using a manually annotated dataset to achieve precise segmentation of the FM, TA, CA, NAVI, and the entire foot boundary. The PCA method facilitated the extraction of principal bone axes for FAM angle evaluations. This approach significantly enhances detection efficiency, accuracy, and objectivity compared to traditional manual methods, providing a consistent and standardized quantitative analysis tool for FAM and PSTT. Additionally, correlation analyses were conducted to assess the influence of sex and age on FAM and PSTT, exploring intra-group trends and establishing a robust framework for further studies on these demographic factors.

Despite the limitation of retrospective study, which poses challenges in controlling data balance across sex and age groups and limiting access to extensive clinical and personal information, the methods developed here to analyze FAM and PSTT using deep learning and data-driven approaches provide a solid foundation for further theoretical and empirical investigations. This methodology not only facilitates enhanced assessments of foot conditions like flatfoot and high arch but also contributes to clinical research, offering insights for personalized medical interventions and footwear design to improve foot health and functionality. This research thus presents a valuable tool for advancing medical and industrial applications in foot health management.

Data availability

The main data generated or analyzed to support the conclusion during this study are included in this published article. The full datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due PRIVACY PROTECTION POLICY AND ETHIC REQUIERMENT but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Keller, T. S. et al. Relationship between vertical ground reaction force and speed during walking, slow jogging, and running. Clin. Biomech. 11(5), 253–259 (1996).

San Tsung, B. Y., Zhang, M., Fan, Y. B. & Boone, D. A. Quantitative comparison of plantar foot shapes under different weight-bearing conditions. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 40(6), 517 (2003).

Teoh, J. C., Shim, V. P. W. & Lee, T. Quantification of plantar soft tissue changes due to aging in various metatarsophalangeal joint angles with realistic tissue deformation. J. Biomech. 47(12), 3043–3049 (2014).

Dimitrieva, A. J., Kenis, V. M. & Sapogovskiy, A. V. Flatfoot or not: Subjective perception of the height of the feet arch among orthopedists. Pediatr. Traumatol. Orthopaed. Reconstruct. Surg. 8(2), 179–184 (2020).

Venkadesan, M. et al. Stiffness of the human foot and evolution of the transverse arch. Nature 579(7797), 97–100 (2020).

Templeton, A. W., McAlister, W. H. & Zim, I. D. Standardization of terminology and evaluation of osseous relationships in congenitally abnormal feet. Am. J. Roentgenol. Radium Ther. Nucl. Med. 93, 374–381 (1965).

Abousayed, M. M., Alley, M. C., Shakked, R. & Rosenbaum, A. J. Adult-acquired flatfoot deformity: Etiology, diagnosis, and management. JBJS Rev. 5, e7 (2017).

Saltzman, C. L., Nawoczenski, D. A. & Talbot, K. D. Measurement of the medial longitudinal arch. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 76, 45–49 (1995).

Weissengruber, G. E. et al. The structure of the cushions in the feet of African elephants (Loxodonta africana). J. Anatomy 209(6), 781–792 (2006).

Wang, Y.-N., Lee, K. & Ledoux, W. R. Histomorphological evaluation of diabetic and non-diabetic plantar soft tissue. Foot Ankle Int. 32(8), 802–810 (2011).

Bojsen-Moller, F. I. N. N. & Flagstad, K. E. Plantar aponeurosis and internal architecture of the ball of the foot. J. Anatomy 121(Pt 3), 599 (1976).

Wearing, S. C., Smeathers, J. E., Yates, B., Urry, S. R. & Dubois, P. Bulk compressive properties of the heel fat pad during walking: A pilot investigation in plantar heel pain. Clin. Biomech. 24(4), 397–402 (2009).

Lopes, A. D., Hespanhol, L. C., Yeung, S. S. & Costa, L. O. P. What are the main running-related musculoskeletal injuries?. Sports Med. 42(10), 891–905 (2012).

Hill, C. L., Gill, T. K., Menz, H. B. & Taylor, A. W. Prevalence and correlates of foot pain in a population-based study: The North West Adelaide health study. J. Foot Ankle Res. 1(1), 1–7 (2008).

Dunn, J. E. et al. Prevalence of foot and ankle conditions in a multiethnic community sample of older adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 159(5), 491–498 (2004).

Nix, S., Smith, M. & Vicenzino, B. Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Foot Ankle Res. 3(1), 1–9 (2010).

Pop-Busui, R. et al. Diabetic neuropathy: A position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 40(1), 136–154 (2017).

Armstrong, D. G., Boulton, A. J. & Bus, S. A. Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N. Engl. J. Med. 376(24), 2367–2375 (2017).

Sensiba, P. R., Coffey, M. J., Williams, N. E., Mariscalco, M. & Laughlin, R. T. Inter- and intraobserver reliability in the radiographic evaluation of adult flatfoot deformity. Foot Ankle Int. 31, 141–145 (2010).

Kido, M. et al. Reproducibility of radiographic methods for assessing longitudinal tarsal axes: Part 1: Consecutive case study. Foot 40, 1–7 (2019).

Kwan, R. L. C., Zheng, Y. P. & Cheing, G. L. Y. The effect of aging on the biomechanical properties of plantar soft tissues. Clin. Biomech. 25(6), 601–605 (2010).

Khor, B. Y. C., Woodburn, J., Newcombe, L. & Barn, R. Plantar soft tissues and Achilles tendon thickness and stiffness in people with diabetes: A systematic review. J. Foot Ankle Res. 14(1), 35 (2021).

Duffin, A. C., Lam, A., Kidd, R., Chan, A. K. F. & Donaghue, K. C. Ultrasonography of plantar soft tissues thickness in young people with diabetes. Diabet. Med. 19(12), 1009–1013 (2002).

Wu, J., Zhang, Y. Z., Gao, Y. & Luo, T. Y. Assessment the reliability of ultrasonography in the imaging of the plantar fascia: A comparative study. BMC Med. Imaging 19(1), 1–7 (2019).

Sun, J. H. et al. Changes in the thickness and stiffness of plantar soft tissues in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 92(9), 1484–1489 (2011).

Boussouar, A. Thickness estimation, automated classification and novelty detection in ultrasound images of the plantar fascia tissues. University of Salford (United Kingdom) (2019).

Belhan, O., Kaya, M. & Gurger, M. The thickness of heel fat-pad in patients with plantar fasciitis. Acta Orthopaed. Traumatol. Turc. 53(6), 463–467 (2019).

Song, X. et al. Medical image analysis based on T2 mapping and intravoxel-incoherent-motion diffusion-weighted imaging in the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. J. Med. Imaging Health Inf. 9(2), 303–307 (2019).

Kayalibay, B., Jensen, G., & van der Smagt, P. CNN-based segmentation of medical imaging data. arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.03056 (2017).

Bidgood, W. D. Jr., Horii, S. C., Prior, F. W. & Van Syckle, D. E. Understanding and using DICOM, the data interchange standard for biomedical imaging. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 4(3), 199–212 (1997).

Mustra, M., Delac, K. & Grgic, M. (Overview of the DICOM standard. In 2008 50th International Symposium ELMAR, vol. 1 39–44 (IEEE, 2008).

Mason, D. SU-E-T-33: Pydicom: An open source DICOM library. Med. Phys. 38(6), 3493–3493 (2011).

Russell, B. C., Torralba, A., Murphy, K. P. & Freeman, W. T. LabelMe: A database and web-based tool for image annotation. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 77, 157–173 (2008).

Musa, P., Al Rafi, F. & Lamsani, M. A Review: Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) methods to help the application of face recognition. In 2018 third International Conference on Informatics and Computing (ICIC) 1–6 (IEEE, 2018).

Han, D. Comparison of commonly used image interpolation methods. In Conference of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Science and Electronics Engineering (ICCSEE 2013) 1556–1559 (Atlantis Press, 2013.

Long, J., Shelhamer, E. & Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 3431–3440 (2015).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5–9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18 234–241 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Badrinarayanan, V., Kendall, A. & Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 39(12), 2481–2495 (2017).

Chen, L. C., Zhu, Y., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F. & Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 801–818 (2018).

Kyurkchiev, N. & Markov, S. Sigmoid Functions: Some Approximation and Modelling Aspects 4 (LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2015).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Liu, Y. C., Tan, D. S., Chen, J. C., Cheng, W. H. & Hua, K. L. Segmenting hepatic lesions using residual attention U-Net with an adaptive weighted dice loss. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP) 3322–3326 (IEEE, 2019).

Khan, K., Rehman, S. U., Aziz, K., Fong, S. & Sarasvady, S. DBSCAN: Past, present and future. In The fifth international conference on the applications of digital information and web technologies (ICADIWT 2014) 232–238 (IEEE, 2014).

Maćkiewicz, A. & Ratajczak, W. Principal components analysis (PCA). Comput. Geosci. 19(3), 303–342 (1993).

Angin, S., Mickle, K. J. & Nester, C. J. Contributions of foot muscles and plantar fascia morphology to foot posture. Gait Post. 61, 238–242 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program China (2022YFC2009500), the Medical Engineering Fund of Fudan University (YG2021-005, YG2022-008), the Fudan-Yiwu Fund (FYX-23-102), and the TZI-ZJU Industrial Program (2023CLG01, 2023CLG01PT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.M. supervised and coordinated project; R.H., L.C. and J.Z. designed research; L. C. directed clinical trials, X.N. and T.R. performed research; X.N. and L.W. analyzed data; and R.H. and X.N. wrote paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ning, X., Ru, T., Zhu, J. et al. Deep learning-assisted segmentation of X-ray images for rapid and accurate assessment of foot arch morphology and plantar soft tissue thickness. Sci Rep 14, 20028 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71025-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71025-x