Abstract

A sense of belonging to a community is a dimension of subjective well-being that is of growing population health interest. We evaluated sex-stratified associations between community belonging and risk of avoidable hospitalization. Adult men and women from the Canadian Community Health Survey (2000–2014) were asked to rate their sense of community belonging (N = 456,415) and were also linked to acute inpatient hospitalizations to 31 March 2018. We used Cox proportional hazards models to assess the association between community belonging and time to hospitalization related to ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) and adjusted for a range of sociodemographic, health, and behavioural confounders. Compared to those who reported intermediate levels of belonging, both very weak and very strong sense of belonging were associated with greater risk of avoidable hospitalization for women (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.12, 1.47, very weak; HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.03, 1.27, very strong), but not for men (HR 1.12, 95% CI 0.97, 1.29, very weak; HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.98, 1.19, very strong). This study suggests that community belonging is associated with risk of ACSC hospitalization for women and provides a foundation for further research on community belonging and population health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Subjective well-being has been recognized as an important predictor of health outcomes and health behaviours, and it has emerged as a significant point of discussion in the areas of health policy and public health intervention1,2,3,4,5,6. One dimension of well-being is one’s sense of belonging to community, which has been characterized as a shared sense of connection and identity to a community7 as well as attachment to and comfort within a community8. The concept of community belonging has been of longstanding research interest9 and has been discussed in the broader research context of place attachment, rootedness and social capital10. Prior research suggests that weaker sense of belonging to one’s community is associated with negative health indicators and outcomes, including self-rated health11,12, self-rated mental health13, unfavourable changes in health-related behaviour14, and unmet healthcare needs15.

Studies have demonstrated associations between various measures of social connection (e.g., social support, loneliness, social isolation) and downstream health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease16, prolonged hospitalization17, hospital-treated infections18, and mortality6,19,20. An important health outcome that is largely unexplored with respect to community belonging is avoidable hospitalization, which is often considered to be that related to ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) that should not require acute hospitalization if appropriately managed in outpatient settings21.

Community belonging is a multi-dimensional concept that draws upon theories of social connections and place attachment10 from a variety of disciplines, including but not limited to sociology, psychology, and health promotion. Notably, Berkman et al. developed an overarching conceptual model that links social networks and health, and drew upon Émile Durkheim’s theories of social integration, John Bowlby’s attachment theory, and social network theory22. Their model suggests that a combination of social processes and psychobiological processes are involved, and can be extended to explain the relationship between community belonging and health-related outcomes, such as avoidable hospitalization. Conceptually, having a weak sense of community belonging may trigger social processes that influence health by: (1) reducing the community contacts available for receiving health-related information; (2) lowering transmission and reinforcement of healthy social norms, behaviours, and attitudes, leading to unfavourable behaviours such as delayed help-seeking and poor treatment adherence, and; (3) decreasing access to community services and resources23. These processes could also influence more proximal pathways, such as increasing one’s chronic stress responses. Ultimately, the combination of these social dynamics stemming from a lack of community belonging could elevate the likelihood of preventable illness requiring hospitalization11,14,24,25.

Aside from a study that found an association between weak community belonging and lower odds of diabetes-related hospitalization among Canadians with diabetes23, no studies have evaluated the relationship between community belonging and avoidable hospitalizations in the general Canadian population, and none have incorporated sex-stratified analyses. A focus on a broader range of upstream psychosocial factors has the potential to inform decision-making for our health and social systems to generate large-scale improvements in health outcomes across populations. The examination of this relationship is of particular interest for Canada, where the universal healthcare system minimizes financial barriers to healthcare but non-financial (e.g., psycho-social) barriers still exist26. The objective of this study is to evaluate the association between community belonging and avoidable hospitalization using a population-based cohort of adult men and women residing in Canada.

Methods

Study design and sample

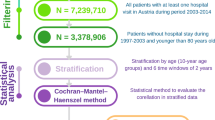

We conducted a population-based cohort study of respondents of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)27, and included survey respondents aged 18–74 years at the time of interview from eight CCHS cycles between 2000 and 2014. Those under 18 were excluded because risk factors for pediatric preventable hospitalizations tend to differ from adult preventable hospitalizations. Consistent with the definition of ACSC hospitalization used in this study21, individuals aged 75 years and older were excluded due to the high prevalence of multiple comorbidities in older adults, posing challenges in distinguishing preventable hospitalizations from those that are not28. Respondents were excluded if they: (1) had a death date preceding interview date, which indicates either an erroneous date of death or linkage); (2) resided in Quebec at the time of interview, as the province of Quebec does not report to the hospitalization database used in this study29, and/or (3) were pregnant at the time of interview, due to the potential for deviation of health and behavioural characteristics (such as BMI and alcohol consumption30) from typical baseline values during pregnancy. We adhered to the principles outlined in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement31. This study was approved by the University of Toronto’s Research Ethics Board (#41965).

Data sources

The CCHS is a cross-sectional survey administered by Statistics Canada, and contains data on community belonging as well as demographic, socioeconomic, behavioural, and health-related factors27. The survey collects health-related data from Canadians 12 years and older and is representative of 98% of the population. Data collection is completed every two years until 2007 and annually thereafter. Individuals are excluded from the survey if they: live on reserves or other Aboriginal settlements, are institutionalized, are a full-time Canadian Forces member or live in the Quebec health regions of Région du Nunavik and Région des Terres-Cries-de-la-Baie-James. The survey data were individually linked to the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) up to 31 March 2018, using a generalized record linkage software (G-link) that utilizes deterministic and probabilistic linkage methods32. The DAD is maintained by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and collects information regarding hospital discharges in all provinces and territories in Canada except Quebec33.

Measures

Exposure: community belonging

Community belonging was captured by the CCHS, which includes a question asking respondents to rate their sense of belonging to their local community on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from very strong, somewhat strong, somewhat weak, to very weak. This single-item measure has been used in prior studies and has been found to be significantly associated with social capital as well as health and mental health outcomes12,14,34. We re-categorized community belonging to a 3-level variable: very strong, intermediate (which includes somewhat strong or somewhat weak), very weak. This categorization focuses on those with the strongest and weakest reported belonging compared to those who felt less strongly about their belonging and were similar. As a sensitivity analysis, we also modelled the 4-level and 2-level categories.

Outcome: avoidable hospitalizations

The DAD was used to obtain information on avoidable hospitalizations from the CCHS interview date to the end of follow-up (31 March 2018). Avoidable hospitalizations were defined as acute care hospitalizations of individuals younger than 75 years old for an ACSC, which include the following: grand mal status and other epileptic convulsions, chronic lower respiratory diseases, asthma, diabetes, heart failure and pulmonary edema, hypertension, and angina21. ACSCs were identified using International Classifications of Disease 9th version (ICD-9) and International Classifications of Disease 10th version (ICD-10) codes (Supplementary Table 1).

Potential confounders

Potential confounders were selected a priori based on support from prior literature (Supplementary Table 2) and the Andersen Newman Framework for determinants of medical care35. The directed acyclic graph (DAG) can be found in the Supplementary Fig. 1. Overall, full adjustment included demographic and socioeconomic factors (age, ethnicity, urban/rural classification, newcomer status, marital status, household income quintile, household education level) as well as health and behavioural factors (alcohol consumption, smoking, physical activity, body mass index, and the presence of four major and common chronic conditions including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/emphysema, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, operationalized as yes/no for each).

Statistical methods

Descriptive analyses of the full range of factors were stratified by sex, community belonging, and ACSC hospitalization status. Weighted Kaplan–Meier survival curves were created to compare ACSC hospitalization across levels of community belonging in women and men. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the hazards associated with the three-level community belonging exposure and the outcome of future ACSC hospitalization for women and men separately. We defined the study time as being from the CCHS interview date to ACSC hospitalization, right-censoring for the study endpoint (March 31, 2018), 75th birthdate or death (maximum follow-up of 18 years). The results of three models are presented: unadjusted (Model 1), intermediately adjusted for survey cycle, demographic and socioeconomic variables (Model 2), and fully adjusted for survey cycle, demographic, socioeconomic, health and behavioural variables (Model 3). Survey weights from Statistics Canada were used to produce nationally representative estimates and account for complex sampling design and non-response bias. Bootstrap weights were incorporated to calculate variance estimates. Missing data were imputed using hot deck imputation methods for item non-response in large-scale surveys36. Imputation cell variables included age, sex, province or territory of residence, and urban/rural residence. Every variable with missing data had non-response rates of less than 5%. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Sensitivity analysis

Provinces and territories transitioned from ICD-9 to ICD-10 over a six-year period beginning in 200137. To assess if the change in coding classification had an impact on the primary analysis, a sensitivity analysis was run limiting the study start date to April 1st, 2004, the date in which all provinces and territories (except for Quebec) implemented ICD-10. To address concerns of selection bias and account for ACSCs at baseline that might impact community belonging, we also conducted an analysis in which ACSC hospitalizations were included if they occurred at least two years after the CCHS interview date. To evaluate the potential impact of bias resulting from hot deck imputation, a model was run utilizing a non-imputed cohort incorporating ‘unknown’ categories for all covariates with missing or unknown responses. A survival model that included self-rated general health as a potential confounder was also run to examine the possibility of residual confounding by self-rated general health.

Results

The final cohort consisted of 456,415 respondents, representing a weighted population of N = 34,332,000 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Both men and women exhibited similar trends in baseline characteristics across levels of community belonging (Table 1). Compared to those who reported very strong belonging, those who reported very weak community belonging were more likely to be younger, be of visible minority status, live in urban areas and report being in the lowest income quintile. Adults with very weak community belonging were also less likely to be married/common-law, have more than secondary school education, be regular drinkers, and be physically active.

Overall, 2.2% of the population experienced one or more ACSC hospitalizations after survey interview. For women, 3.3% of those with weak sense of belonging were hospitalized for an ACSC, whereas only 2.4% of those with strong sense of belonging were hospitalized for an ACSC. Among men, 3.3% of those with weak sense of belonging were hospitalized for an ACSC, while 3% of those with strong sense of belonging were hospitalized for an ACSC (Table 1). Those who experienced ACSC hospitalizations during follow-up were more likely to be older, be widowed, separated, or divorced, report being in the lowest income quintile, be current light smokers, and have poor self-rated health—compared to individuals who did not experience ACSC hospitalizations during follow-up. Adults who experienced ACSC hospitalization were also less likely to: be visible minorities, have more than secondary school education, be physically active, and be of normal BMI status (Table 2).

Graphical assessment of the differences in time to ACSC hospitalization across levels of community belonging using Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that women with very weak belonging appear to have the least favourable outcomes in terms of time-to-hospitalization, followed by women with very strong belonging (Fig. 1). Men with very weak belonging and men with very strong belonging appear to have similarly less favourable outcomes in terms of time-to-hospitalization, compared to men reporting somewhat strong/weak community belonging. Table 3 presents sex-stratified Cox proportional hazard models for the association between community belonging and time to first ACSC hospitalization after survey response. In unadjusted models (Model 1), both very weak and very strong community belonging, compared to intermediate levels of belonging, were associated with a significant increase in risk of avoidable hospitalizations in women (very weak: HR 1.82, 95% CI 1.60, 2.07; very strong: HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.30, 1.59) and in men (very weak: HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.25–1.68; very strong: HR 1.42, 95% CI: 1.29–1.56).

Adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic variables (Model 2) and additionally for health and behavioural factors (Model 3) attenuated associations between community belonging and avoidable hospitalization. Compared to women with intermediate sense of belonging, women who report very weak community belonging have a 29% greater risk of avoidable hospitalization (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.12, 1.47) while women who report very strong community belonging have a 15% greater risk for avoidable hospitalization (HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.03, 1.27). However, these associations were not observed in men (very weak: HR 1.12, 95% CI 0.97, 1.29; very strong: HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.98, 1.19).

The sensitivity analyses consisting of the lagged ACSC hospitalization outcome (Supplementary Table 3), adjustment for self-rated general health (Supplementary Table 4), restriction to outcomes ascertained using ICD-10 (Supplementary Table 5), and a non-imputed cohort that included missing variables as a separate category (Supplementary Table 6) resulted in similar effect sizes to the primary analysis, and no changes in the direction of risk. In addition, we re-ran the analysis using both the 4-level and 2-level variations of community belonging and while direct comparisons are not possible given the different referent group, we observed the same findings of increased risk for low community belonging among females (Supplementary Tables 7–8).

Ethics approval, and consent to participate in the survey was obtained by Statistics Canada. All analyses were conducted under project number 21-MAPA-UTO-7020 at the University of Toronto site of the Canadian Research Data Centre Network, a secure laboratory which provides access to micro-data holdings of Statistics Canada and has in place a detailed protocol to protect the confidentiality of respondents. Consistent with this protocol, all frequencies have a rounding base to the nearest five respondents, and tabulations resulting in cell-counts under 30 individuals were not released.

Discussion

Our study examined the relationship between community belonging and avoidable hospitalizations using a population-based cohort of Canadian adults. After adjusting for potential confounders, both very strong and very weak community belonging, compared to intermediate sense of community belonging, were associated with an increased risk in ACSC hospitalization, however the association is more pronounced for very weak community belonging compared to very strong. After fully adjusting for confounders, these associations remained conclusive among women, but not men. A previous study reported an 80 per cent increased odds of diabetes hospitalization among adults 45 years and older with pre-existing diabetes who reported weak, compared to strong, community belonging23. This is consistent with our findings related to those reporting very weak community belonging. Our findings are also in line with studies that demonstrate the importance of social connections for favourable hospitalization outcomes17,38,39. A recent study that found individuals who reported low life satisfaction had almost three times the risk of ACSC hospitalization compared to those who reported the highest level of life satisfaction3, while another found that weaker sense of belonging was associated with longer length of stay in hospital—most strongly among older adults17.

Current studies generally report a dose–response relationship between stronger community belonging and favourable health outcomes12,14,40, for which we find partial support. In addition to observing higher risk of avoidable hospitalization among those with very weak belonging, we found that those reporting very strong belonging were also at higher risk of avoidable hospitalization. In spite of our efforts to account for a variety of potential demographic, socioeconomic, health and behavioural factors, our findings could be vulnerable to residual confounding, although alternative explanations for the negative health impacts of social capital have been proposed41. A strong sense of community belonging could place more demands, responsibility, and obligation on the individual to contribute to their community, potentially leading to elevated levels of stress. In much the same way as individuals can adopt and emulate others’ beneficial health behaviours, those closely connected to a community with unhealthy or harmful health practices may likewise adopt these behaviors, and in turn, face greater risk of adverse health consequences. Regardless, this finding warrants further investigation into this relationship and other risk factors and conditions that could be driving this pattern.

Few studies have conducted sex-based analyses of the relationship between social connections and down-stream health outcomes with which to compare our findings, and those that exist have produced mixed results. A Finnish study of 206 older men and women found that low social support was associated with higher mortality risk for women, but not men19. The authors of this study suggested this difference could have been related to the fact that women in the study were more likely than men to be widowed and living alone, and thus more dependent on social connections. In contrast, an older study of Finnish men and women demonstrated a graded association between social connections and mortality for men, but not for women20. With respect to the relationship between self-rated health and sense of community belonging, we observed little difference between men and women12. The potential for community belonging to improve health outcomes for women versus men may also vary based on the aspects or types of social connections under consideration, as one study of community belonging and depression suggests42. The relationship between a variety of risk factors (such as comorbidity, socioeconomic status, and physical activity) and ACSC hospitalizations are known to differ for women and men in Canada43. Furthermore, other sex- and gender-based differences in health (i.e. biological/social factors, traditional gender roles) and behaviours (e.g. healthcare seeking patterns) could impact the relationship between subjective well-being and healthcare utilization. More research on the mechanisms behind such sex-based differences is needed to inform health and social policy, and suggests such policies need to be tailored to men and women.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has multiple strengths. First, the use of record-linked data provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the individual-level association between hospitalizations and community belonging—a measure that is not commonly captured in administrative data. Second, we aimed to reduce bias and improve accuracy by accounting for time at risk and adjusting for a variety of demographic, socioeconomic, health and behavioural factors. Third, we conducted several sensitivity analyses accounting for potential bias arising from variations in administrative data collection, missing data, and residual confounding, all of which provided evidence for the robustness of our primary results.

Our study also has limitations. First, there may be risk of measurement error in the covariates given the self-reported nature of the CCHS. This is a particularly important consideration for the exposure, as community belonging is a subjective concept that may be understood differently across different subgroups,11,25 including sex44. Furthermore, the CCHS and DAD captures data on sex, but not gender, so we were limited in our ability to explore gender-based variations in belonging and how differences in socialization might impact the relationship between community belonging and avoidable hospitalization. However, this is still a growing area of research, and at present, this single-item measure of community belonging has been shown to be an efficient and parsimonious measure that captures community belonging as well as related aspects such as social capital and attachment to place10,34. A second and related limitation is that we were not able to account for change in residence across the follow-up period. Moving to a different neighbourhood could lead to changes in one’s sense of belonging to their local community, as social connections are presumably lost in one place and built in another. We hypothesize however that such variations over time would bias our results toward the null. That we still detected significant associations without accounting for neighbourhood changes underscores the potential strength of the relationship between community belonging and avoidable hospitalizations. A third limitation is that we were only able to ascertain death for those with a discharge disposition indicating death in the DAD, thus, there is a risk of incomplete censoring for those who died outside of hospital or before the collection of discharge disposition data in ICD-10. Fourth, although we adjusted for many potential confounders, we were limited to the information available on the survey and administrative data and our results remain vulnerable to residual confounding. Lastly, while our findings are not fully generalizable to all of Canada (as the DAD does not capture data from Quebec and the CCHS has several population exclusions), our study does capture a large sample from the majority of Canadian provinces and territories and utilizes survey weights to account for non-response bias and the sampling strategy of the survey.

Conclusion

We observed that women with very strong and very weak self-reported sense of belonging to their local community had increased risk of avoidable hospitalization, while no conclusive associations by community belonging were found for men. These findings add to the current growing literature on the importance of subjective well-being to health, provide a foundation for further research on the association between community belonging and hospitalization, and draws attention to the importance of sex to variations in subjective well-being and health. Future studies should build upon this work and consider examining the impacts of life stage on community belonging and its relationship to sex-specific population health outcomes. This study may help inform decision-makers regarding strategies and policies aimed to reduce avoidable hospitalizations in Canada.

Data availability

Statistics Canada for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data (contact Statistics Canada Regional Data Centres at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/rdc/process).

References

Diener, E. & Chan, M. Y. Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 3(1), 1–43 (2011).

Helliwell, J., Layard, R. & Sachs, J. World Happiness Report 2017. New York; 2017.

De Prophetis, E., Goel, V., Watson, T. & Rosella, L. C. Relationship between life satisfaction and preventable hospitalisations: A population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMJ Open 10(2), e032837 (2020).

Goel, V., Rosella, L. C., Fu, L. & Alberga, A. The relationship between life satisfaction and healthcare utilization: A longitudinal study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 55(2), 142–150 (2018).

Rosella, L. C., Longdi, F., Buajitti, E. & Goel, V. Death and chronic disease risk associated with poor life satisfaction: A population-based cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 188(2), 323–331 (2018).

Renwick, K. A., Sanmartin, C., Dasgupta, K., Berrang-Ford, L. & Ross, N. The influence of low social support and living alone on premature mortality among aging Canadians. Can. J. Public Health 111, 594–605 (2020).

Tartaglia, S. A preliminary study for a new model of sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 34(1), 25–36 (2006).

Kitchen, P., Williams, A. & Chowhan, J. Sense of community belonging and health in Canada: A regional analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 107(1), 103–126 (2012).

McMillan, D. W. & Chavis, D. M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 14(1), 6–23 (1986).

Schellenberg, G., Lu, C. H., Schimmele, C. & Hou, F. The correlates of self-assessed community belonging in Canada: Social capital, neighbourhood characteristics, and rootedness. Soc. Indic. Res. 140(2), 597–618 (2018).

Ross, N. Community belonging and health. Health Rep. 13(3), 33–39 (2002).

Michalski, C. A., Diemert, L. M., Helliwell, J. F., Goel, V. & Rosella, L. C. Relationship between sense of community belonging and self-rated health across life stages. SSM Popul. Health 12, 100676 (2020).

Shields, M. Community belonging and self-perceived health. Health Rep. 19(2), 51–60 (2008).

Hystad, P. & Carpiano, R. M. Sense of community-belonging and health-behaviour change in Canada. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 66(3), 277–283 (2012).

Baiden, P., den Dunnen, W., Arku, G. & Mkandawire, P. The role of sense of community belonging on unmet health care needs in Ontario, Canada: Findings from the 2012 Canadian community health survey. J. Public Health 22(5), 467–478 (2014).

Hakulinen, C. et al. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for myocardial infarction, stroke and mortality: UK Biobank cohort study of 479 054 men and women. Heart 104(18), 1536 (2018).

Renwick, K. A., Sanmartin, C., Dasgupta, K., Berrang-Ford, L. & Ross, N. The influence of psychosocial factors on hospital length of stay among aging Canadians. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 8, 23337214221138440 (2022).

Elovainio, M. et al. Association of social isolation and loneliness with risk of incident hospital-treated infections: An analysis of data from the UK Biobank and Finnish Health and Social Support studies. Lancet Public Health 8(2), e109–e118 (2023).

Lyyra, T.-M. & Heikkinen, R.-L. Perceived social support and mortality in older people. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 61(3), S147–S152 (2006).

Kaplan, G. A. et al. Social connections and mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease: Prospective evidence from Eastern Finland. Am. J. Epidemiol. 128(2), 370–380 (1988).

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions 2021. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/indicators/ambulatory-care-sensitive-conditions

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I. & Seeman, T. E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 51, 843–857 (2000).

Gupta, N. & Sheng, Z. Reduced risk of hospitalization with stronger community belonging among aging Canadians living with diabetes: Findings from linked survey and administrative data. Front. Public Health 9, 670082 (2021).

Duncan, D. & Kawachi, I. Neighborhoods and Health 2nd edn. (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Kawachi, I. & Berkman, L. F. Social capital, social cohesion, and health. In Social Epidemiology 2nd edn (eds Berkman, L. F., Kawachi, I. & Glymour, M. M.) 290–319. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780195377903.003.0008 (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Health Canada. “Certain Circumstances”: Issues in Equity and Responsiveness in Access to Health Care in Canada (Health Canada, 2001).

Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey—Annual Component (CCHS). 2021 [updated 10 Jun 2021. Available from: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3226

Jackson, G. & Tobias, M. Potentially avoidable hospitalisations in New Zealand, 1989–98. Aust. N. Zeal. J. Public Health 25(3), 212–221 (2001).

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Data Quality Documentation, Discharge Abstract Database - Multi-Year Information. Ottawa, ON; 2012.

Walker, M. J., Al-Sahab, B., Islam, F. & Tamim, H. The epidemiology of alcohol utilization during pregnancy: An analysis of the Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey (MES). BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 11(1), 52 (2011).

von Elm, E. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. The Lancet 370(9596), 1453–1457 (2007).

Fellegi, I. & Sunter, A. A theory for record linkage. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 64(328), 1183–1210 (1969).

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Discharge Abstract Database metadata (DAD) 2022. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/discharge-abstract-database-metadata-dad

Carpiano, R. M. & Hystad, P. W. Sense of community belonging” in health surveys: What social capital is it measuring?. Health Place 17(2), 606–617 (2011).

Andersen, R. & Newman, J. F. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Meml. Fund Q. Health Soc. 51, 95–124 (1973).

Andridge, R. R. & Little, R. J. A. A review of hot deck imputation for survey non-response. Int. Stat. Rev. 78(1), 40–64 (2010).

Walker, R. L. et al. Implementation of ICD-10 in Canada: How has it impacted coded hospital discharge data?. BMC Health Serv. Res. 12(1), 149 (2012).

Murayama, H., Fujiwara, Y. & Kawachi, I. Social capital and health: A review of prospective multilevel studies. J. Epidemiol. 22(3), 179–187 (2012).

Schultz, B. E., Corbett, C. F., Hughes, R. G. & Bell, N. Scoping review: Social support impacts hospital readmission rates. J. Clin. Nurs. 31(19–20), 2691–2705 (2022).

Anderson, S., Currie, C. L. & Copeland, J. L. Sedentary behavior among adults: The role of community belonging. Prev. Med. Rep. 4, 238–241 (2016).

Villalonga-Olives, E. & Kawachi, I. The dark side of social capital: A systematic review of the negative health effects of social capital. Soc. Sci. Med. 194, 105–127 (2017).

Fowler, K., Wareham-Fowler, S. & Barnes, C. Social context and depression severity and duration in Canadian men and women: Exploring the influence of social support and sense of community belongingness. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 43(S1), E85–E96 (2013).

Sanmartin, C. A., Khan, S. & Team, L. R. Hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC): The factors that matter: Statistics Canada, Health Information and Research Division; 2011.

Fuhrer, R. & Stansfeld, S. A. How gender affects patterns of social relations and their impact on health: A comparison of one or multiple sources of support from “close persons”. Soc. Sci. Med. 54(5), 811–825 (2002).

Acknowledgements

All analyses were conducted at the Toronto Region Statistics Canada Research Data Centre of the Canadian Research Data Centre Network (CRDCN). The services and activities provided by the CRDCN are made possible by the financial or in-kind support of SSHRC, CIHR, CFI, Statistics Canada and participating universities whose support is gratefully acknowledged. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Statistics Canada, CRDCN, or the Government of Canada. This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Priority Announcement for Population and Public Health held by L.C.R (FRN 72064429). S.M.M. was supported through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Postdoctoral Fellowship (FRN 72063084). L.C.R. was supported through a Canada Research Chair in Population Health Analytics (FRN 72060091) and the Stephen Family Research Chair in Community Health at Trillium Health Partners. Funding organizations had no role in the study design, data analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, nor the decision to submit the article for publication. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceptualised and designed the study. All authors contributed to the statistical design of the study and M.L. conducted the data analyses. M.L. had direct access to the dataset. All authors interpreted the data. M.L. and S.M. conducted the literature search and M.L. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript. L.R. had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, M., Mah, S.M. & Rosella, L.C. Sense of belonging to community and avoidable hospitalization: a population-based cohort study of 456,415 Canadians. Sci Rep 14, 21142 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71128-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71128-5